Leo Martello

Leo Martello | |

|---|---|

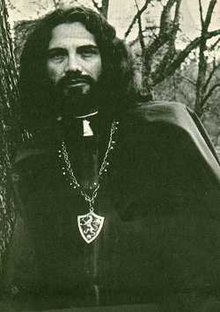

Martello in 1970 | |

| Born | September 26, 1930 Dudley, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | June 29, 2000 (aged 69) |

| Occupations |

|

Leo Martello (September 26, 1930 – June 29, 2000) was an American Wiccan priest, gay rights activist, and author. He was a founding member of the Strega Tradition, a form of the modern Pagan new religious movement of Wicca which drew upon his own Italian heritage. During his lifetime he published a number of books on such esoteric subjects as Wicca, astrology, and tarot reading.

Born to a working-class Italian American family in Dudley, Massachusetts, he was raised Roman Catholic although became interested in esotericism as a teenager. He later claimed that when he was 21, relatives initiated him into a tradition of witchcraft inherited from their Sicilian ancestors; this conflicts with other statements that he made, and there is no independent evidence to corroborate his claim. During the 1950s, he was based in New York City, where he worked as a graphologist and hypnotist. After beginning to publish books on paranormal topics in the early 1960s, he publicly began identifying as Wiccan in 1969, and stated that he was involved in a New York coven.

After the Stonewall riots of 1969, Martello – himself a gay man – involved himself in gay rights activism, becoming a member of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). Leaving the GLF following an internal schism, he became a founding member of the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA) and authored a regular column, "The Gay Witch", for its newspaper. In 1970 he founded the Witches International Craft Associates (WICA) as a networking organization for Wiccans, and under its auspices organized a "Witch In" that took place in Central Park at Halloween 1970, despite opposition from the New York City Parks Department. To campaign for the civil rights of Wiccans, he founded the Witches Anti-Defamation League, which was later renamed the Alternative Religions Education Network. In 1973, he visited England, there being initiated into Gardnerian Wicca by the Gardnerian High Priestess Patricia Crowther. He continued practicing Wicca into the 1990s, when he retreated from public life, eventually succumbing to cancer in 2000.

Early life

[edit]Youth: 1930–49

[edit]Martello was born on September 26, 1930, in Dudley, Massachusetts, being raised on a small farm rented by his father, the Italian immigrant Rocco Luigi Martello.[1] Following the economic turmoil of the Great Depression, the Martellos were forced from their land and moved first to Worcester, Massachusetts and then to Southbridge, Massachusetts.[1] It was here that Leo was baptized into the Roman Catholic Church, but his parents divorced soon after. Unable to care for him alone, his father sent Martello to the Catholic boarding preparatory school attached to Assumption College, Worcester, which was run by the Augustinians of the Assumption. He spent six years at the school, later describing it as the unhappiest period of his life.[1] He studied graphology and from the age of 16 began making radio appearances as a graphologist, also writing stories for magazines.[2]

"It is extremely doubtful that there ever was a Sicilian tradition of Wicca that had been passed down through the [Martello] family, yet it is possible that Martello's cousins had created their own Wiccan coven, or that they had instead been members of a folk magical tradition which Martello then embellished. Equally, the entire scenario could be fiction."

Martello later claimed to have experienced psychic phenomena as a child, sparking his interest in occultism. By his early teenage years, he had begun studying palmistry and tarot card reading with a woman named Marta.[1] He also later claimed that his father had informed him that his grandmother, Maria Concetta, had been a psychic known as a Strega Maga ("Great Witch") in her hometown of Enna, Sicily, Italy. According to Martello's account, Concetta had worked as a folk magician and tarot card reader, and attracted the hatred and envy of the local Catholic clergy. He also related that on one occasion, she had killed a Mafioso using magic when he threatened her husband for not paying protection money.[4] Martello related that when he was 16, his father told him that he had cousins in New York City who wished to meet him. He proceeded to do so and – according to his account – they informed him that they were initiates of an ancient Italian witchcraft religion, La Vecchia ("the Old Religion"). After identifying his possession of psychic powers, they initiated him into the tradition on his 21st birthday in 1951, making him swear an oath never to reveal the secrets of the La Vecchia.[5] Moving to the city, he studied at Hunter College and the Institute for Psychotherapy.[4]

Martello never produced any proof to support his claims, and there is no independent evidence that corroborate them.[6] An anonymous woman who had known Martello informed the researcher Michael G. Lloyd that during the 1980s, he had told her that he had never been initiated into a tradition of Witchcraft, and that he had simply embraced occultism in the 1960s in order to earn a living.[6] The Pagan studies scholar Ethan Doyle White expressed criticism of Martello's claims, noting that it was "extremely doubtful" that a tradition of Wicca could have been passed down through Martello's Sicilian family. Instead, he suggested that Martello might have been instructed in a tradition of folk magic that he later embellished into a form of Wicca, that the cousins themselves had constructed a form of Wicca that they passed on to Martello, or that the entire scenario had been a fabrication of Martello's.[3]

New York City: 1950–68

[edit]Based in New York City, in 1950 Martello founded the American Hypnotism Academy, continuing to direct the organization until 1954.[4] From 1955 to 1957, he served as treasurer of the American Graphological Society, and worked as a freelance graphologist for such corporate clients as the Unifonic Corporation of America and the Associated Special Investigators International.[7] He also published a column titled "Your Handwriting Tells" for eight years that ran in the Chelsea Clinton News, and supplied various articles on the subject of graphology to different magazines.[8] In the city, he also began to frequent the gay scene.[8] In 1955, Martello was awarded a Doctorate in Divinity by a non-accredited organization, the National Congress of Spiritual Consultants, a clearing house for registered yet unaffiliated ministers.[7] That year, he founded the Temple of Spiritual Guidance, taking on the role of Pastor, which he would continue in until 1960, when he began to focus on his writing and his new philosophy of "psychoselfism".[7] In 1961 he published his first book, Your Pen Personality, in which he discussed the manner in which handwriting could be used to reveal the personality of the writer.[8] Martello corresponded with California-based Pagan Victor Henry Anderson, and it was at Martello's encouragement that Anderson established his Mahaelani Coven circa 1960.[9]

Martello claimed that in the summer of 1964, he moved to Tangier, Morocco, where he researched the history of the tarot, resulting in the publication of It's in the Cards (1964).[7] Returning to the U.S. in 1965, he moved into an apartment in Greenwich Village, New York City, writing a book on astrology, It's Written in the Stars, and a book on psychic protection, How to Prevent Psychic Blackmail.[8] He also began attending the Spiritualist gatherings that were operated by Clifford Bias at the Ansonia Hotel.[8] At some point High Priestess Lori Bruno founded a witchcraft coven and church, Our Lord and Lady of the Trinacrian Rose, in which Leo was acknowledged as Elder.[3] In 1969 he publicly revealed himself to be a practitioner of Witchcraft; claiming that he had gained the permission of his coven to do so.[10] Intent on countering the negative publicity that Wicca had been receiving, he published The Weird Ways of Witchcraft in 1969, the same year that he also published The Hidden World of Hypnotism.[11]

Public activism

[edit]Gay Liberation: 1969–70

[edit]In July 1969, Martello attended an open meeting of the Mattachine Society's New York branch. He was appalled at the Society's negative reaction to the Stonewall riots, and castigated those gay people in the audience who accepted the categorization of homosexuality as a mental illness, accusing them of being self-loathing. He proceeded to publish his thoughts in an essay in which he stated that "homosexuality is not a problem in itself. The problem is society's attitude towards it."[12] Those gay rights activists who rejected the Mattachine Society's approach and who favored a confrontational stance against the police and authorities founded the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), with Martello elected the group's first moderator.[13] Martello supported the GLF's stance that condemned "this rotten, dirty, vile, fucked-up capitalist conspiracy" that dominated American society, and he volunteered by producing articles both for the group's newsletter Come Out! and for the wider press.[13] He was involved in the GLF's campaign against The Village Voice's decision to ban the word "gay" from advertisements; the magazine preferred the term "homophile", which had also been used by the Mattachine Society. Wanting to break from previous gay liberation organizations, the GLF embraced the term "gay", with Martello dismissing "homophile" as sounding like a nail file for homosexuals.[13]

The GLF was structured around a system of anarchic consensus, which made it difficult for the group to reach conclusions on any issue, and heated arguments became commonplace at its meetings.[14] In November 1969, the group's membership voted to provide political and financial support to the Black Panthers, an armed African-American leftist group. This was heavily controversial among the GLF, given the homophobic nature of the Black Panthers, and resulted in a walk-out of many senior members, including Martello, Arthur Evans, Arthur Bell, Lige Clarke, and Jack Nichols.[14] That month, Martello was invited to a private meeting of these disaffected GLF members which resulted in the formation of the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA). Although continuing the GLF's emphasis on taking a confrontational approach to conventional American society and authority, the group was more tightly organized and structured, and focused exclusively on attaining equal rights for gay and lesbian people.[15] The businessman Al Goldstein agreed to invest $25,000 in the GAA's new venture, a newspaper written by, and aimed at, the country's gay community. It was launched in December 1969 as GAY, and it soon gained a readership of 25,000. Martello contributed a regular column known as "The Gay Witch", reaching his widest audience to date, also authoring a variety of other articles that appeared in it.[16]

WICA and WADL: 1970–74

[edit]In 1970, Martello founded the Witches International Craft Associates (WICA), through which he issued The WICA Newsletter, set up to explain what Witchcraft and Wicca was to the wider public and to serve as a resource through which occultists could contact one another.[17] In April 1970 he appeared on the WNEW-TV Channel 5 documentary series Helluva Town, performing Witchcraft rites with several assistants in Central Park.[18] That year saw one of New York's first substantial gatherings of occultists, the Festival of Occult Arts, as well as the first Earth Day celebration and the first Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day parade. These events inspired Martello's desire to hold a public Witchcraft Sabbat celebration.[19] Acting under the auspices of WICA, in late summer he approached the New York City Parks Department asking for permission to hold a "Witch-In" in Sheep Meadow, at the south end of Central Park, on October 31, 1970. The Department refused, and when Martello stated that the Witchcraft community would gather there regardless in their capacity as private individuals, he was threatened with police action. Martello gained the legal assistance of the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU), who informed the Parks Department that they were in breach of the First Amendment. The Department subsequently reversed their decision, and the event went ahead.[20]

"Where do I begin to write about a legend? A man who gave tirelessly of himself for the fight for human rights, animal rights, gay and lesbian rights, and for Witches worldwide to worship in complete freedom? Leo Martello was an amazingly compassionate man. He never turned away anyone who genuinely needed his time and effort in the pursuit of a just cause. He fought long and hard for the freedom of Witches and Pagans."

Inspired by his victory over the Parks Department, Martello founded an organization devoted to campaigning for the religious rights of Witches, the Witches Anti-Defamation League (WADL), which would eventually be renamed the Alternative Religions Education Network (AREN).[22] For WADL, he authored an essay titled "The Witch Manifesto", likely influenced by Carl Wittman's "Refugees from Amerika: A Gay Manifesto" (1970), which demanded that the Roman Catholic Church face a tribunal for crimes committed against accused witches in the Early Modern period and that they pay reparations to the modern Witchcraft community for those actions.[23] During this decade he authored a column for Gnostica magazine which was titled "Wicca Basket", a pun on the phonetic similarity between "Wicca" and "wicker".[24]

In 1971, a young gay Wiccan named Eddie Buczynski contacted Martello, and requested initiation. Due to Buczynski's inexperience in the religion, Martello turned him down, although developed a friendship with him. Martello introduced Buczynski both to other covens who might initiate him, and to Herman Slater, who would become his long-time partner.[25] Slater was ill with various medical complications, and on one occasion was rehabilitating at the New York University Medical Center when Martello performed a healing ritual on him with the assistance of Buczynski.[26] Martello would come to be known as a regular at The Warlock Shop, an occult store opened by Slater in New York.[27] Through The WICA Newsletter, Martello had met Lady Gwen Thompson, the founder of the New England Covens of Traditionalist Witches (NECTW), and decided to introduce Buczynski to her, resulting in Buczynski's initiation into the tradition in Spring 1972.[28] Martello and Thompson later fell out, with some unconfirmed accounts claiming that it was because he lent her money and she did not pay him back.[29] In October 1972, Buczynski founded his own tradition of Wicca, termed Welsh Traditionalist Witchcraft, with Martello becoming an early initiate and taking on the name of "Nemesis" within that tradition.[30] In turn, Martello welcomed Buczynski into his La Vecchia tradition, and initiated him through its three degree system.[31]

In November 1972, Martello lectured at the first Friends of the Craft conference, held at New York's First Unitarian Church.[32] In April 1973, he moved to England for six months, where he was initiated and trained in the three degrees of Gardnerian Wicca by the Sheffield coven run by Patricia Crowther and her husband Arnold Crowther.[33] He continued to encourage acceptance of homosexuality within the Pagan and Witchcraft community, authoring an article titled "The Gay Pagan" for Green Egg magazine.[34] He expressed the view that homophobic Wiccans were "sexually insecure" and that they viewed the religion simply as "a ritual means of fornication".[35] He was also among the prominent male Pagans to endorse feminist and female-only variants of Wicca, such as the Dianic Wicca promoted by Zsuzsanna Budapest.[36]

Later life

[edit]During the 1990s, Martello retired from his public work.[37] Doyle White noted that while Martello faded from prominence as the head of the Strega Wicca movement, the tradition gained a "new public advocate" in Raven Grimassi.[3] Martello died of cancer on June 29, 2000.[38] Bruno was the executrix of his estate.[37]

Personal life

[edit]Lloyd described Martello as "a lanky, hungry scrapper with piercing eyes, the face of a dark angel, and a mouth like a bear trap",[39] while in her encyclopaedia on Wicca, Rosemary Ellen Guiley described him as "a colourful figure, known for his humor".[40] Bruno described him as "a loving man, yet sometimes caustic", stating that to know him "was an honor, and ever a challenge".[21] He was often noted for his scruffy appearance, with him typically wearing second-hand clothes.[41]

Beliefs

[edit]Martello defended the growing rise of feminists in Wicca during the 1970s, criticizing what he deemed to be the continual repression of women within the Pagan movement.[42] He also espoused the view that any Pagan who was involved in the U.S. government or military was a hypocrite.[43] He was critical of Wiccans who espoused a division between white magic and black magic, commenting that it had racial overtones and that many of those advocating such a view were racist.[44]

Although aware that historians had criticized the witch-cult hypothesis of Margaret Murray, Martello stood by her claims, believing that the cult had been passed through oral tradition and thus evaded appearing in the textual sources studied by historians.[45]

Martello thought it unimportant that many Wiccans had lied about the origins of their beliefs, being quoted by Pagan journalist Margot Adler in her book Drawing Down the Moon as having stated

Let's assume that many people lied about their lineage. Let's further assume that there are no covens on the current scene that have any historical basis. The fact remains: they do exist now. And they can claim a spiritual lineage going back thousands of years. All of our pre-Judeo-Christian or Moslem ancestors were Pagans![46]

Publications

[edit]| Year of publication | Title | Publisher |

|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Your Pen Personality | Self-published |

| 1964 | It's in the Cards: The Atomic-Age Approach to Card Reading Using Psychological and Parapsychological Principles | Key Publications |

| 1966 | It's in the Stars: A Sensible Approach to and a Psychological Evaluation of Astrology in this "Age of Enlightenment" | Key Publications |

| 1966 | How to Prevent Psychic Blackmail: The Philosophy of Psychoselfism | S. Weiser |

| 1969 | Weird Ways of Witchcraft | HC Publishers |

| 1969 | Hidden World of Hypnotism: How to Hypnotize | HC Publishers |

| 1971 | Curses in Verses: Spelltime in Rhyme | Hero Press |

| 1972 | Black Magic, Satanism, Voodoo | Castle Books |

| 1972 | Understanding the Tarot | Castle Books |

| 1973 | Witchcraft: The Old Religion | University Books |

| 1990 | Reading the Tarot: Understanding the Cards of Destiny | Perigee Trade |

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, p. 64.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b c d Doyle White 2016, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, p. 65.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, p. 65; Doyle White 2016, p. 50.

- ^ a b Lloyd 2012, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d e Lloyd 2012, p. 66.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, p. 68.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, pp. 68–69; Doyle White 2016, p. 50.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Lloyd 2012, p. 75.

- ^ a b Lloyd 2012, p. 76.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 226; Lloyd 2012, p. 79; Doyle White 2016, p. 51.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 79.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Adler 2006, p. 136; Guiley 2008, p. 226; Lloyd 2012, pp. 80–82; Doyle White 2016, p. 51.

- ^ a b Bruno n.d.

- ^ Adler 2006, p. 136; Guiley 2008, p. 226; Lloyd 2012, p. 83.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 226; Lloyd 2012, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Clifton 2006, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 87.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 90.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 116.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 95.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 127.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 128.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 229.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 168.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 193.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 114.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 60.

- ^ a b Guiley 2008, p. 226.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 226; Lloyd 2012, p. 554; Bruno n.d..

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 64.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 225.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 228.

- ^ Adler 2006, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Adler 2006, p. 388.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 192; Doyle White 2016, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 81.

- ^ Adler 2006, p. 85.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adler, Margot (2006) [1979]. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshipers and Other Pagans in America (revised ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303819-1.

- Bruno, Lori (n.d.). "Dr. Leo Louis Martello - A Memorial". Our Lord and Lady of the Trinacrian Rose. Archived from the original on January 2, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Clifton, Chas S. (2006). Her Hidden Children: The Rise of Wicca and Paganism in America. Oxford and Lanham: AltaMira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0202-6.

- Doyle White, Ethan (2016). Wicca: History, Belief, and Community in Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Brighton, Chicago, and Toronto: Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84519-754-4.

- Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2008). The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca (third ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816071043.

- Lloyd, Michael G. (2012). Bull of Heaven: The Mythic Life of Eddie Buczynski and the Rise of the New York Pagan. Hubbarston, MAS.: Asphodel Press. ISBN 978-1938197048.

- 1930 births

- 2000 deaths

- American expatriates in Morocco

- American feminist writers

- American former Christians

- American graphologists

- American occult writers

- American psychics

- American Wiccans

- American writers of Italian descent

- Deaths from cancer in the United States

- Former Roman Catholics

- Founders of modern pagan movements

- Gardnerian Wiccans

- Gay feminists

- American gay writers

- American hypnotists

- LGBTQ feminists

- LGBTQ people from Massachusetts

- American LGBTQ rights activists

- LGBTQ Wiccans

- American male feminists

- American feminists

- People associated with the tarot

- Wiccan feminists

- Wiccan priests

- Wiccan writers

- Writers from Massachusetts

- People from Southbridge, Massachusetts

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 20th-century American male writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- 20th-century American LGBTQ people