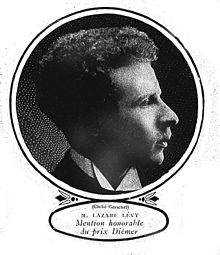

Lazare Lévy

Lazare Lévy, also hyphenated as Lazare-Lévy,[1] (18 January 1882 – 20 September 1964) was an influential French pianist, organist, composer and pedagogue. As a virtuoso pianist he toured throughout Europe, in North Africa, Israel, the Soviet Union and Japan.[citation needed] He taught for many years at the Paris Conservatoire.

Biography

[edit]Lazare Lévy was born of French parents in Brussels, Belgium. After early lessons with an English piano teacher there,[2] he entered the Paris Conservatoire at age 12 in 1894. He studied under Louis Diémer, André Gedalge, and Albert Lavignac. His fellow musicians and friends included Jacques Thibaud, Alfredo Casella, Maurice Ravel, Alfred Cortot, George Enescu, and Pierre Monteux. In 1898, he was awarded a Premier Prix.[3]

He was conducted by Édouard Colonne at his début récital at the age twenty. He played Schumann's A minor Piano Concerto at the Concerts Colonne. Camille Saint-Saëns, who saw him at one of his early recitals, considered him to possess "that rare union of technical perfection and musicality."[3] Saint-Saëns intentionally obtained a front row seat to show his support for the pianist.[4]

In 1911, he played Book I of "Iberia" by Isaac Albéniz, whom he admired. He also supported French composers Darius Milhaud and Paul Dukas early in their careers by playing their works.[3] Having an interest in new music, he also championed the careers of several of his students.[5]

He co-wrote Méthode Supérieure for piano when he was 25. He became an assistant of Diémer, who published the piece.[3] Beginning in 1914, he became a temporary teacher at the Paris Conservatoire. He became a professor in 1923 and taught there until 1953, except for the period during the war[3] when the Germans had dismissed him because he was a Jew holding an official position.[6][7] However, his position has been given to Marcel Ciampi and although he was reappointed in 1944, he did not get the same position after the war.[3] He was a leading performer and influential teacher, along with Alfred Cortot, Isidor Philipp, and Marguerite Long.[8]

During World War II, he refused to play on the radio, which was controlled by the Germans.[9] He evaded capture as a Jew by using false papers, taking other names, and hiding out. Phillipe, his son, was a resistance fighter, who was captured and sent to Drancy concentration camp. The SS officer Alois Brunner tortured him[3] and he was murdered.[7]

Among his pupils were Agnelle Bundervoët,[6] Jean Langlais,[10] Clara Haskil,[11] Lukas Foss,[12] Solomon, John Cage, and Monique Haas.[5] See: List of music students by teacher: K to M#Lazare Lévy.

Lazare Lévy died in 1964,[3] aged 82.

References

[edit]- ^ "L'Ecole Lazare-Lévy". Music Web International. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ George Grove (1954). Eric Blom (ed.). Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. V (5th ed.). Macmillan. p. 155.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Allan Evans; Frédéric Gaussin (2007). "Masters of the French Piano Tradition: Francis Planté and his peers". Arbiter Records. Flushing, New York.

- ^ Brian Rees (2 August 2012). Camille Saint-Saëns: A Life. Faber & Faber. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-571-28705-5.

- ^ a b Rob Haskins (15 February 2013). John Cage. Reaktion Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-86189-943-9.

- ^ a b "Agnelle Bundervoët". Bach Cantatas. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ a b Madeleine Forte (22 September 2011). Simply Madeleine: The Memoir of a Post–World War II French Pianist. Author House. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-4634-3385-7.

- ^ Charles Timbrell (1999). French Pianism: A Historical Perspective. Amadeus Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-57467-045-5.

- ^ Ann Labounsky (2000). Jean Langlais: The Man and His Music. Amadeus Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-57467-054-7.

- ^ Ann Labounsky (2000). Jean Langlais: The Man and His Music. Amadeus Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-57467-054-7.

- ^ Stephen Siek (10 November 2016). A Dictionary for the Modern Pianist. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-8108-8880-7.

- ^ Jonathan D. Green (2003). A Conductor's Guide to Choral-orchestral Works. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8108-4720-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Charles Timbrell (1999). French Pianism: A Historical Perspective. Amadeus Press. pp. 112–118, + many other pages. ISBN 978-1-57467-045-5.

- 20th-century French male classical pianists

- 20th-century French classical pianists

- French piano educators

- 20th-century French Jews

- Levites

- French expatriates in Belgium

- Musicians from Brussels

- 1882 births

- 1964 deaths

- Jewish classical pianists

- Conservatoire de Paris alumni

- Academic staff of the École Normale de Musique de Paris

- Academic staff of the Conservatoire de Paris