Languages of Uzbekistan

| Languages of Uzbekistan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official | Uzbek[1] |

| Semi-official | Russian |

| Recognised | Persian Kyrgyz Turkmen Kazakh Pashto |

| Regional | Karakalpak (Karakalpakstan) |

| Minority | Dungan, Erzya, Koryo-mar, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Southern Uzbek, Tatar |

| Foreign | English |

| Signed | Russian Sign Language |

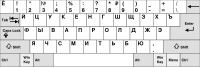

| Keyboard layout | |

The majority language of Uzbekistan is the Uzbek language. However, many other native languages are spoken in the country. These include several other Turkic languages, Persian and Russian. The official language of government according to current legislation is Uzbek, while the Republic of Karakalpakstan has the right to determine its own official language. Russian and other languages may be used facultatively in certain public institutions, such as notary services and in contact between government institutions and citizens, and the choice of languages in individual life, interethnic communication and education is free.[2] In practice, alongside Uzbek, Russian remains the language most used in public life. There are no language requirements for the citizenship of Uzbekistan.[3]

Turkic languages

[edit]The Uzbek language is one of the Turkic languages close to the Uyghur language, and both of them belong to the Karluk languages branch of the Turkic language family. Uzbek language is the only official state language,[4] and since 1992 is officially written in the Latin alphabet, with heavy usage of the Cyrillic alphabet throughout the country.

Karakalpak, is also a Turkic language, but it is closer to Kazakh. It is spoken in the Republic of Karakalpakstan by close to half a million people and has an official status there. More than 800,000 people also speak the Kazakh language.[citation needed]

Before the 1920s, the written language of Uzbeks was called Turki (known to Western scholars as Chagatai) and used the Nastaʿlīq script. In 1926 the Latin alphabet was introduced and went through several revisions throughout the 1930s. Finally, in 1940, the Cyrillic alphabet was introduced by Soviet authorities and was used until the fall of Soviet Union. In 1993 Uzbekistan shifted back to the Latin script (Uzbek alphabet), which was modified in 1996 and has been taught in schools since 2000. Schools, colleges, and universities teach only in Latin script. Cyrillic is used in a number of popular newspapers and websites. Some of the text on the TV on some channels is duplicated in the Cyrillic alphabet. Cyrillic is popular with the older generation of Uzbeks who grew up on this alphabet.[5]

Indo-European languages

[edit]Russian

[edit]Although the Russian language is not formally declared an official language in the country, it is widely used in all fields, including official documents. Russian and Uzbek are the permissible languages of notary institutions and registry offices.[6] Thus, the Russian language is the de facto second official language in Uzbekistan. Russian is an important language for interethnic communication, especially in the cities, including much day-to-day technical, scientific, governmental and business use. The country is also home to approximately one million people whose native language is Russian.[7][8][9][3][10] The local dialect is Uzbekistani Russian.

Persian

[edit]

The Persian language is widespread throughout Uzbekistan, being spoken by anywhere between 10-20% of the population, especially in the cities of Bukhara and Samarkand which remain predominantly Persian-speaking.[11] It is also found in large pockets in Kasansay, Chust, Rishtan and Sokh and Chodak in Ferghana Valley, as well as in Burchmulla, Ahangaran, Baghistan in the middle Syr Darya district, and finally in, Shahrisabz, Qarshi, Kitab and the river valleys of Kafiringan and Chaganian. Foltz notes that Persian-speakers in Uzbekistan are mostly bilingual in Uzbek and tend to see themselves as Uzbeks "who also happen to speak Persian".[12]

References

[edit]- ^ "Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan". constitution.uz. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan "On Official Language"" (PDF). Refworld. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ a b Languages in Uzbekistan Archived 11 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Facts and Details

- ^ Mansurov, Nasim (8 December 1992). "Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan". Umid.uz. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Kamp, Marianne (2008). The New Woman in Uzbekistan: Islam, Modernity, and Unveiling Under Communism. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98819-1. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015.

- ^ "Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan "On Official Language"" (PDF). Refworld. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ Юрий Подпоренко (2001). "Бесправен, но востребован. Русский язык в Узбекистане". Дружба Народов. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Евгений Абдуллаев (2009). "Русский язык: жизнь после смерти. Язык, политика и общество в современном Узбекистане". Неприкосновенный запас. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ А. Е. Пьянов. "СТАТУС РУССКОГО ЯЗЫКА В СТРАНАХ СНГ". 2011. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ "Uzbekistan's Russian-Language Conundrum". Eurasianet.org. 19 September 2006. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Foltz, Richard (2023). A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East, 2nd edition. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 173-190. ISBN 978-0-7556-4964-8.

- ^ Foltz, Richard (2023). A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East, 2nd edition. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-7556-4964-8.