LIGO

The LIGO Livingston control room as it was during Advanced LIGO's first observing run (O1) | |

| Alternative names | LIGO |

|---|---|

| Location(s) | Hanford Site, Washington and Livingston, Louisiana, US |

| Coordinates | LIGO Hanford Observatory: 46°27′18.52″N 119°24′27.56″W / 46.4551444°N 119.4076556°W LIGO Livingston Observatory: 30°33′46.42″N 90°46′27.27″W / 30.5628944°N 90.7742417°W |

| Organization | LIGO Scientific Collaboration |

| Wavelength | 43 km (7.0 kHz)–10,000 km (30 Hz) |

| Built | 1994–2002 |

| First light | 23 August 2002 |

| Telescope style | gravitational-wave observatory |

| Length | 4,000 m (13,123 ft 4 in) |

| Website | www |

LIGO observatories in the Contiguous United States | |

| | |

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) is a large-scale physics experiment and observatory designed to detect cosmic gravitational waves and to develop gravitational-wave observations as an astronomical tool.[1] Two large observatories were built in the United States with the aim of detecting gravitational waves by laser interferometry. These observatories use mirrors spaced four kilometers apart to measure changes in length—over an effective span of 1120 km—of less than one ten-thousandth the charge diameter of a proton.[2]

The initial LIGO observatories were funded by the United States National Science Foundation (NSF) and were conceived, built and are operated by Caltech and MIT.[3][4] They collected data from 2002 to 2010 but no gravitational waves were detected.

The Advanced LIGO Project to enhance the original LIGO detectors began in 2008 and continues to be supported by the NSF, with important contributions from the United Kingdom's Science and Technology Facilities Council, the Max Planck Society of Germany, and the Australian Research Council.[5][6] The improved detectors began operation in 2015. The detection of gravitational waves was reported in 2016 by the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LSC) and the Virgo Collaboration with the international participation of scientists from several universities and research institutions. Scientists involved in the project and the analysis of the data for gravitational-wave astronomy are organized by the LSC, which includes more than 1000 scientists worldwide,[7][8][9] as well as 440,000 active Einstein@Home users as of December 2016[update].[10]

LIGO is the largest and most ambitious project ever funded by the NSF.[11][12] In 2017, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne and Barry C. Barish "for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves".[13]

Observations are made in "runs". As of January 2022[update], LIGO has made three runs (with one of the runs divided into two "subruns"), and made 90 detections of gravitational waves.[14][15] Maintenance and upgrades of the detectors are made between runs. The first run, O1, which ran from 12 September 2015 to 19 January 2016, made the first three detections, all black hole mergers. The second run, O2, which ran from 30 November 2016 to 25 August 2017, made eight detections: seven black hole mergers and the first neutron star merger.[16] The third run, O3, began on 1 April 2019; it was divided into O3a, from 1 April to 30 September 2019, and O3b, from 1 November 2019[17] until it was suspended on 27 March 2020 due to COVID-19.[18] The O3 run included the first detection of the merger of a neutron star with a black hole.[15]

The gravitational wave observatories LIGO, Virgo in Italy, and KAGRA in Japan are coordinating to continue observations after the COVID-caused stop, and LIGO's O4 observing run started on 24 May 2023.[19][20] LIGO projects a sensitivity goal of 160–190 Mpc for binary neutron star mergers (sensitivities: Virgo 80–115 Mpc, KAGRA greater than 1 Mpc).[21]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]

The LIGO concept built upon early work by many scientists to test a component of Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, the existence of gravitational waves. Starting in the 1960s, American scientists including Joseph Weber, as well as Soviet scientists Mikhail Gertsenshtein and Vladislav Pustovoit, conceived of basic ideas and prototypes of laser interferometry,[22][23] and in 1967 Rainer Weiss of MIT published an analysis of interferometer use and initiated the construction of a prototype with military funding, but it was terminated before it could become operational.[24] Starting in 1968, Kip Thorne initiated theoretical efforts on gravitational waves and their sources at Caltech, and was convinced that gravitational wave detection would eventually succeed.[22]

Prototype interferometric gravitational wave detectors (interferometers) were built in the late 1960s by Robert L. Forward and colleagues at Hughes Research Laboratories (with mirrors mounted on a vibration isolated plate rather than free swinging), and in the 1970s (with free swinging mirrors between which light bounced many times) by Weiss at MIT, and then by Heinz Billing and colleagues in Garching Germany, and then by Ronald Drever, James Hough and colleagues in Glasgow, Scotland.[25]

In 1980, the NSF funded the study of a large interferometer led by MIT (Paul Linsay, Peter Saulson, Rainer Weiss), and the following year, Caltech constructed a 40-meter prototype (Ronald Drever and Stan Whitcomb). The MIT study established the feasibility of interferometers at a 1-kilometer scale with adequate sensitivity.[22][26]

Under pressure from the NSF, MIT and Caltech were asked to join forces to lead a LIGO project based on the MIT study and on experimental work at Caltech, MIT, Glasgow, and Garching. Drever, Thorne, and Weiss formed a LIGO steering committee, though they were turned down for funding in 1984 and 1985. By 1986, they were asked to disband the steering committee and a single director, Rochus E. Vogt (Caltech), was appointed. In 1988, a research and development proposal achieved funding.[22][26][27][28][29][30]

From 1989 through 1994, LIGO failed to progress technically and organizationally. Only political efforts continued to acquire funding.[22][31] Ongoing funding was routinely rejected until 1991, when the U.S. Congress agreed to fund LIGO for the first year for $23 million. However, requirements for receiving the funding were not met or approved, and the NSF questioned the technological and organizational basis of the project.[27][28] By 1992, LIGO was restructured with Drever no longer a direct participant.[22][31][32][33] Ongoing project management issues and technical concerns were revealed in NSF reviews of the project, resulting in the withholding of funds until they formally froze spending in 1993.[22][31][34][35]

In 1994, after consultation between relevant NSF personnel, LIGO's scientific leaders, and the presidents of MIT and Caltech, Vogt stepped down and Barry Barish (Caltech) was appointed laboratory director,[22][32][36] and the NSF made clear that LIGO had one last chance for support.[31] Barish's team created a new study, budget, and project plan with a budget exceeding the previous proposals by 40%. Barish proposed to the NSF and National Science Board to build LIGO as an evolutionary detector, where detection of gravitational waves with initial LIGO would be possible, and with advanced LIGO would be probable.[37] This new proposal received NSF funding, Barish was appointed Principal Investigator, and the increase was approved. In 1994, with a budget of US$395 million, LIGO stood as the largest overall funded NSF project in history. The project broke ground in Hanford, Washington in late 1994 and in Livingston, Louisiana in 1995. As construction neared completion in 1997, under Barish's leadership two organizational institutions were formed, LIGO Laboratory and LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LSC). The LIGO laboratory consists of the facilities supported by the NSF under LIGO Operation and Advanced R&D; this includes administration of the LIGO detector and test facilities. The LIGO Scientific Collaboration is a forum for organizing technical and scientific research in LIGO. It is a separate organization from LIGO Laboratory with its own oversight. Barish appointed Weiss as the first spokesperson for this scientific collaboration.[22][27]

Observations begin

[edit]Initial LIGO operations between 2002 and 2010 did not detect any gravitational waves. In 2004, under Barish, the funding and groundwork were laid for the next phase of LIGO development (called "Enhanced LIGO"). This was followed by a multi-year shut-down while the detectors were replaced by much improved "Advanced LIGO" versions.[38][39] Much of the research and development work for the LIGO/aLIGO machines was based on pioneering work for the GEO600 detector at Hannover, Germany.[40][41] By February 2015, the detectors were brought into engineering mode in both locations.[42]

In mid-September 2015, "the world's largest gravitational-wave facility" completed a five-year US$200-million overhaul, bringing the total cost to $620 million.[9][43] On 18 September 2015, Advanced LIGO began its first formal science observations at about four times the sensitivity of the initial LIGO interferometers.[44] Its sensitivity was to be further enhanced until it was planned to reach design sensitivity around 2021.[update][45]

Detections

[edit]On 11 February 2016, the LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration published a paper about the detection of gravitational waves, from a signal detected at 09.51 UTC on 14 September 2015 of two ~30 solar mass black holes merging about 1.3 billion light-years from Earth.[46][47]

Current executive director David Reitze announced the findings at a media event in Washington D.C., while executive director emeritus Barry Barish presented the first scientific paper of the findings at CERN to the physics community.[48]

On 2 May 2016, members of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration and other contributors were awarded a Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics for contributing to the direct detection of gravitational waves.[49]

On 16 June 2016 LIGO announced a second signal was detected from the merging of two black holes with 14.2 and 7.5 times the mass of the Sun. The signal was picked up on 26 December 2015, at 3:38 UTC.[50]

The detection of a third black hole merger, between objects of 31.2 and 19.4 solar masses, occurred on 4 January 2017 and was announced on 1 June 2017.[51][52] Laura Cadonati was appointed the first deputy spokesperson.[53]

A fourth detection of a black hole merger, between objects of 30.5 and 25.3 solar masses, was observed on 14 August 2017 and was announced on 27 September 2017.[54]

In 2017, Weiss, Barish, and Thorne received the Nobel Prize in Physics "for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves." Weiss was awarded one-half of the total prize money, and Barish and Thorne each received a one-quarter prize.[55][56][57]

After shutting down for improvements, LIGO resumed operation on 26 March 2019, with Virgo joining the network of gravitational-wave detectors on 1 April 2019.[58] Both ran until 27 March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic halted operations.[18] During the COVID shutdown, LIGO underwent a further upgrade in sensitivity, and observing run O4 with the new sensitivity began on 24 May 2023.[19]

Mission

[edit]

LIGO's mission is to directly observe gravitational waves of cosmic origin. These waves were first predicted by Einstein's general theory of relativity in 1916, when the technology necessary for their detection did not yet exist. Their existence was indirectly confirmed when observations of the binary pulsar PSR 1913+16 in 1974 showed an orbital decay which matched Einstein's predictions of energy loss by gravitational radiation. The Nobel Prize in Physics 1993 was awarded to Hulse and Taylor for this discovery.[60]

Direct detection of gravitational waves had long been sought. Their discovery has launched a new branch of astronomy to complement electromagnetic telescopes and neutrino observatories. Joseph Weber pioneered the effort to detect gravitational waves in the 1960s through his work on resonant mass bar detectors. Bar detectors continue to be used at six sites worldwide. By the 1970s, scientists including Rainer Weiss realized the applicability of laser interferometry to gravitational wave measurements. Robert Forward operated an interferometric detector at Hughes in the early 1970s.[61]

In fact as early as the 1960s, and perhaps before that, there were papers published on wave resonance of light and gravitational waves.[62] Work was published in 1971 on methods to exploit this resonance for the detection of high-frequency gravitational waves. In 1962, M. E. Gertsenshtein and V. I. Pustovoit published the very first paper describing the principles for using interferometers for the detection of very long wavelength gravitational waves.[63] The authors argued that by using interferometers the sensitivity can be 107 to 1010 times better than by using electromechanical experiments. Later, in 1965, Braginsky extensively discussed gravitational-wave sources and their possible detection. He pointed out the 1962 paper and mentioned the possibility of detecting gravitational waves if the interferometric technology and measuring techniques improved.

Since the early 1990s, physicists have thought that technology has evolved to the point where detection of gravitational waves—of significant astrophysical interest—is now possible.[64]

In August 2002, LIGO began its search for cosmic gravitational waves. Measurable emissions of gravitational waves are expected from binary systems (collisions and coalescences of neutron stars or black holes), supernova explosions of massive stars (which form neutron stars and black holes), accreting neutron stars, rotations of neutron stars with deformed crusts, and the remnants of gravitational radiation created by the birth of the universe. The observatory may, in theory, also observe more exotic hypothetical phenomena, such as gravitational waves caused by oscillating cosmic strings or colliding domain walls.

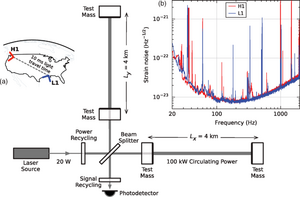

Observatories

[edit]LIGO operates two gravitational wave observatories in unison: the LIGO Livingston Observatory (30°33′46.42″N 90°46′27.27″W / 30.5628944°N 90.7742417°W) in Livingston, Louisiana, and the LIGO Hanford Observatory, on the DOE Hanford Site (46°27′18.52″N 119°24′27.56″W / 46.4551444°N 119.4076556°W), located near Richland, Washington. These sites are separated by 3,002 kilometers (1,865 miles) straight line distance through the earth, but 3,030 kilometers (1,883 miles) over the surface. Since gravitational waves are expected to travel at the speed of light, this distance corresponds to a difference in gravitational wave arrival times of up to ten milliseconds. Through the use of trilateration, the difference in arrival times helps to determine the source of the wave, especially when a third similar instrument like Virgo, located at an even greater distance in Europe, is added.[65]

Each observatory supports an L-shaped ultra high vacuum system, measuring four kilometers (2.5 miles) on each side. Up to five interferometers can be set up in each vacuum system.

The LIGO Livingston Observatory houses one laser interferometer in the primary configuration. This interferometer was successfully upgraded in 2004 with an active vibration isolation system based on hydraulic actuators providing a factor of 10 isolation in the 0.1–5 Hz band. Seismic vibration in this band is chiefly due to microseismic waves and anthropogenic sources (traffic, logging, etc.).

The LIGO Hanford Observatory houses one interferometer, almost identical to the one at the Livingston Observatory. During the Initial and Enhanced LIGO phases, a half-length interferometer operated in parallel with the main interferometer. For this 2 km interferometer, the Fabry–Pérot arm cavities had the same optical finesse, and, thus, half the storage time as the 4 km interferometers. With half the storage time, the theoretical strain sensitivity was as good as the full length interferometers above 200 Hz but only half as good at low frequencies. During the same era, Hanford retained its original passive seismic isolation system due to limited geologic activity in Southeastern Washington.

Operation

[edit]

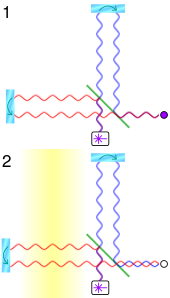

The parameters in this section refer to the Advanced LIGO experiment. The primary interferometer consists of two beam lines of 4 km length which form a power-recycled Michelson interferometer with Gires–Tournois etalon arms. A pre-stabilized 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser emits a beam with a power of 20 W that passes through a power recycling mirror. The mirror fully transmits light incident from the laser and reflects light from the other side increasing the power of the light field between the mirror and the subsequent beam splitter to 700 W. From the beam splitter the light travels along two orthogonal arms. By the use of partially reflecting mirrors, Fabry–Pérot cavities are created in both arms that increase the effective path length of laser light in the arm from 4 km to approximately 1,200 km.[66] The power of the light field in the cavity is 100 kW.[67]

When a gravitational wave passes through the interferometer, the spacetime in the local area is altered. Depending on the source of the wave and its polarization, this results in an effective change in length of one or both of the cavities. The effective length change between the beams will cause the light currently in the cavity to become very slightly out of phase (antiphase) with the incoming light. The cavity will therefore periodically get very slightly out of coherence and the beams, which are tuned to destructively interfere at the detector, will have a very slight periodically varying detuning. This results in a measurable signal.[68]

After an equivalent of approximately 280 trips down the 4 km length to the far mirrors and back again,[69] the two separate beams leave the arms and recombine at the beam splitter. The beams returning from two arms are kept out of phase so that when the arms are both in coherence and interference (as when there is no gravitational wave passing through), their light waves subtract, and no light should arrive at the photodiode. When a gravitational wave passes through the interferometer, the distances along the arms of the interferometer are shortened and lengthened, causing the beams to become slightly less out of phase. This results in the beams coming in phase, creating a resonance, hence some light arrives at the photodiode and indicates a signal. Light that does not contain a signal is returned to the interferometer using a power recycling mirror, thus increasing the power of the light in the arms.

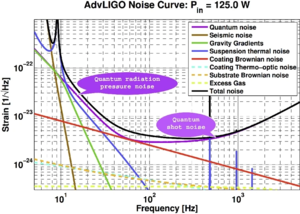

In actual operation, noise sources can cause movement in the optics, producing similar effects to real gravitational wave signals; a great deal of the art and complexity in the instrument is in finding ways to reduce these spurious motions of the mirrors.[70] Background noise and unknown errors (which happen daily) are in the order of 10−20, while gravitational wave signals are around 10−22. After noise reduction, a signal-to-noise ratio around 20 can be achieved, or higher when combined with other gravitational wave detectors around the world.[71]

Observations

[edit]

Based on current models of astronomical events, and the predictions of the general theory of relativity,[72][73][74] gravitational waves that originate tens of millions of light years from Earth are expected to distort the 4-kilometre (2.5 mi) mirror spacing by about 10−18 m, less than one-thousandth the charge diameter of a proton. Equivalently, this is a relative change in distance of approximately one part in 1021. A typical event which might cause a detection event would be the late stage inspiral and merger of two 10-solar-mass black holes, not necessarily located in the Milky Way galaxy, which is expected to result in a very specific sequence of signals often summarized by the slogan chirp, burst, quasi-normal mode ringing, exponential decay.

In their fourth Science Run at the end of 2004, the LIGO detectors demonstrated sensitivities in measuring these displacements to within a factor of two of their design.

During LIGO's fifth Science Run in November 2005, sensitivity reached the primary design specification of a detectable strain of one part in 1021 over a 100 Hz bandwidth. The baseline inspiral of two roughly solar-mass neutron stars is typically expected to be observable if it occurs within about 8 million parsecs (26×106 ly), or the vicinity of the Local Group, averaged over all directions and polarizations. Also at this time, LIGO and GEO 600 (the German-UK interferometric detector) began a joint science run, during which they collected data for several months. Virgo (the French-Italian interferometric detector) joined in May 2007. The fifth science run ended in 2007, after extensive analysis of data from this run did not uncover any unambiguous detection events.

In February 2007, GRB 070201, a short gamma-ray burst arrived at Earth from the direction of the Andromeda Galaxy. The prevailing explanation of most short gamma-ray bursts is the merger of a neutron star with either a neutron star or a black hole. LIGO reported a non-detection for GRB 070201, ruling out a merger at the distance of Andromeda with high confidence. Such a constraint was predicated on LIGO eventually demonstrating a direct detection of gravitational waves.[75]

Enhanced LIGO

[edit]

After the completion of Science Run 5, initial LIGO was upgraded with certain technologies, planned for Advanced LIGO but available and able to be retrofitted to initial LIGO, which resulted in an improved-performance configuration dubbed Enhanced LIGO.[76] Some of the improvements in Enhanced LIGO included:

- Increased laser power

- Homodyne detection

- Output mode cleaner

- In-vacuum readout hardware

Science Run 6 (S6) began in July 2009 with the enhanced configurations on the 4 km detectors.[77] It concluded in October 2010, and the disassembly of the original detectors began.

Advanced LIGO

[edit]

After 2010, LIGO went offline for several years for a major upgrade, installing the new Advanced LIGO detectors in the LIGO Observatory infrastructures.

The project continued to attract new members, with the Australian National University and University of Adelaide contributing to Advanced LIGO, and by the time the LIGO Laboratory started the first observing run 'O1' with the Advanced LIGO detectors in September 2015, the LIGO Scientific Collaboration included more than 900 scientists worldwide.[9]

The first observing run operated at a sensitivity roughly three times greater than Initial LIGO,[79] and a much greater sensitivity for larger systems with their peak radiation at lower audio frequencies.[80]

On 11 February 2016, the LIGO and Virgo collaborations announced the first observation of gravitational waves.[47][67] The signal, named GW150914,[67][81] was recorded on 14 September 2015, just two days after Advanced LIGO started collecting data following the upgrade.[47][82][83] It matched the predictions of general relativity[72][73][74] for the inward spiral and merger of a pair of black holes and subsequent ringdown of the resulting single black hole. The observations demonstrated the existence of binary stellar-mass black hole systems and the first observation of a binary black hole merger.

On 15 June 2016, LIGO announced the detection of a second gravitational wave event, recorded on 26 December 2015, at 3:38 UTC. Analysis of the observed signal indicated that the event was caused by the merger of two black holes with masses of 14.2 and 7.5 solar masses, at a distance of 1.4 billion light years.[50] The signal was named GW151226.[84]

The second observing run (O2) ran from 30 November 2016[85] to 25 August 2017,[86] with Livingston achieving 15–25% sensitivity improvement over O1, and with Hanford's sensitivity similar to O1.[87] In this period, LIGO saw several further gravitational wave events: GW170104 in January; GW170608 in June; and five others between July and August 2017. Several of these were also detected by the Virgo Collaboration.[88][89][90] Unlike the black hole mergers which are only detectable gravitationally, GW170817 came from the collision of two neutron stars and was also detected electromagnetically by gamma ray satellites and optical telescopes.[89]

The third run (O3) began on 1 April 2019[91] and was planned to last until 30 April 2020; in fact it was suspended in March 2020 due to COVID-19.[18][92][93] On 6 January 2020, LIGO announced the detection of what appeared to be gravitational ripples from a collision of two neutron stars, recorded on 25 April 2019, by the LIGO Livingston detector. Unlike GW170817, this event did not result in any light being detected. Furthermore, this is the first published event for a single-observatory detection, given that the LIGO Hanford detector was temporarily offline at the time and the event was too faint to be visible in Virgo's data.[94]

The fourth observing run (O4) was planned to start in December 2022,[95] but was postponed until 24 May 2023. O4 is projected to continue until February 2025.[19] As of O4, the interferometers are operating at a sensitivity of 155-175 Mpc,[19] within the design sensitivity range of 160-190 Mpc for binary neutron star events.[96]

The fifth observing run (O5) is projected to begin in late 2025 or in 2026.[19]

Future

[edit]LIGO-India

[edit]LIGO-India, or INDIGO, is a planned collaborative project between the LIGO Laboratory and the Indian Initiative in Gravitational-wave Observations (IndIGO) to create a gravitational-wave detector in India. The LIGO Laboratory, in collaboration with the US National Science Foundation and Advanced LIGO partners from the U.K., Germany and Australia, has offered to provide all of the designs and hardware for one of the three planned Advanced LIGO detectors to be installed, commissioned, and operated by an Indian team of scientists in a facility to be built in India.

The LIGO-India project is a collaboration between LIGO Laboratory and the LIGO-India consortium: Institute of Plasma Research, Gandhinagar; IUCAA (Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics), Pune and Raja Ramanna Centre for Advanced Technology, Indore.

The expansion of worldwide activities in gravitational-wave detection to produce an effective global network has been a goal of LIGO for many years. In 2010, a developmental roadmap[97] issued by the Gravitational Wave International Committee (GWIC) recommended that an expansion of the global array of interferometric detectors be pursued as a highest priority. Such a network would afford astrophysicists with more robust search capabilities and higher scientific yields. The current agreement between the LIGO Scientific Collaboration and the Virgo collaboration links three detectors of comparable sensitivity and forms the core of this international network. Studies indicate that the localization of sources by a network that includes a detector in India would provide significant improvements.[98][99] Improvements in localization averages are predicted to be approximately an order of magnitude, with substantially larger improvements in certain regions of the sky.

The NSF was willing to permit this relocation, and its consequent schedule delays, as long as it did not increase the LIGO budget. Thus, all costs required to build a laboratory equivalent to the LIGO sites to house the detector would have to be borne by the host country.[100] The first potential distant location was at AIGO in Western Australia,[101] however the Australian government was unwilling to commit funding by 1 October 2011 deadline.

A location in India was discussed at a Joint Commission meeting between India and the US in June 2012.[102] In parallel, the proposal was evaluated by LIGO's funding agency, the NSF. As the basis of the LIGO-India project entails the transfer of one of LIGO's detectors to India, the plan would affect work and scheduling on the Advanced LIGO upgrades already underway. In August 2012, the U.S. National Science Board approved the LIGO Laboratory's request to modify the scope of Advanced LIGO by not installing the Hanford "H2" interferometer, and to prepare it instead for storage in anticipation of sending it to LIGO-India.[103] In India, the project was presented to the Department of Atomic Energy and the Department of Science and Technology for approval and funding. On 17 February 2016, less than a week after LIGO's landmark announcement about the detection of gravitational waves, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that the Cabinet has granted 'in-principle' approval to the LIGO-India mega science proposal.[104]

A site near pilgrimage site of Aundha Nagnath in the Hingoli district of state Maharashtra in western India has been selected.[105][106]

On 7 April 2023, the LIGO-India project was approved by the Cabinet of Government of India. Construction is to begin in Maharashtra's Hingoli district at a cost of INR 2600 crores.[107]

A+

[edit]Like Enhanced LIGO, certain improvements will be retrofitted to the existing Advanced LIGO instrument. These are referred to as A+ proposals, and are planned for installation starting from 2019 until the upgraded detector is operational in 2024.[108] The changes would almost double Advanced LIGO's sensitivity,[109][110] and increase the volume of space searched by a factor of seven.[111] The upgrades include:

- Improvements to the mirror suspension system.[112]

- Increased reflectivity of the mirrors.

- Using frequency-dependent squeezed light, which would simultaneously decrease radiation pressure at low frequencies and shot noise at high frequencies, and

- Improved mirror coatings with lower mechanical loss.[113]

Because the final LIGO output photodetector is sensitive to phase, and not amplitude, it is possible to squeeze the signal so there is less phase noise and more amplitude noise, without violating the quantum mechanical limit on their product.[114] This is done by injecting a "squeezed vacuum state" into the dark port (interferometer output) which is quieter, in the relevant parameter, than simple darkness. Such a squeezing upgrade was installed at both LIGO sites prior to the third observing run.[115] The A+ improvement will see the installation of an additional optical cavity that acts to rotate the squeezing quadrature from phase-squeezed at high frequencies (above 50 Hz) to amplitude-squeezed at low frequencies, thereby also mitigating low-frequency radiation pressure noise.

LIGO Voyager

[edit]A third-generation detector at the existing LIGO sites is being planned under the name "LIGO Voyager" to improve the sensitivity by an additional factor of two, and halve the low-frequency cutoff to 10 Hz.[116] Plans call for the glass mirrors and 1064 nm lasers to be replaced by even larger 160 kg silicon test masses, cooled to 123 K (a temperature achievable with liquid nitrogen), and a change to a longer laser wavelength in the 1500–2200 nm range at which silicon is transparent. (Many documents assume a wavelength of 1550 nm, but this is not final.)

Voyager would be an upgrade to A+, to be operational around 2027–2028.[117]

Cosmic Explorer

[edit]A design for a larger facility with longer arms is called "Cosmic Explorer". This is based on the LIGO Voyager technology, has a similar LIGO-type L-shape geometry but with 40 km arms. The facility is currently planned to be on the surface. It has a higher sensitivity than Einstein Telescope for frequencies beyond 10 Hz, but lower sensitivity under 10 Hz.[116]

See also

[edit]- BlackGEM

- Einstein Telescope, a European third-generation gravitational wave detector

- Einstein@Home, a volunteer distributed computing program one can download in order to help the LIGO/GEO teams analyze their data

- GEO600, a gravitational wave detector located in Hannover, Germany

- Holometer

- North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves

- Richard A. Isaacson

- PyCBC, an open source software package to help analyze LIGO data

- Tests of general relativity

- Virgo interferometer, an interferometer located close to Pisa, Italy

- Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA)

- LISA Pathfinder

- Taiji Program in Space, a space-based Chinese gravitational wave detector

Notes

[edit]- ^ Barish, Barry C.; Weiss, Rainer (October 1999). "LIGO and the Detection of Gravitational Waves". Physics Today. 52 (10): 44. Bibcode:1999PhT....52j..44B. doi:10.1063/1.882861.

- ^ "Facts". LIGO. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

This is equivalent to measuring the distance from Earth to the nearest star to an accuracy smaller than the width of a human hair!

(that is, to Proxima Centauri at 4.0208×1013 km). - ^ "LIGO Lab Caltech MIT". Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "LIGO MIT". Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Major research project to detect gravitational waves is underway". University of Birmingham News. University of Birmingham. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ Shoemaker, David (2012). "The evolution of Advanced LIGO" (PDF). LIGO Magazine (1): 8.

- ^ "Revolutionary Grassroots Astrophysics Project "Einstein@Home" Goes Live". Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ "LSC/Virgo Census". myLIGO. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Castelvecchi, Davide (15 September 2015), "Hunt for gravitational waves to resume after massive upgrade: LIGO experiment now has better chance of detecting ripples in space-time", Nature, 525 (7569): 301–302, Bibcode:2015Natur.525..301C, doi:10.1038/525301a, PMID 26381963

- ^ "BOINCstats project statistics". Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Larger physics projects in the United States, such as Fermilab, have traditionally been funded by the Department of Energy.

- ^ "LIGO: The Search for Gravitational Waves". www.nsf.gov. National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2017". Nobel Foundation.

- ^ "LSC News".

- ^ a b "LSC News".

- ^ The LIGO Scientific Collaboration; the Virgo Collaboration; Abbott, B. P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T. D.; Abraham, S.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adhikari, R. X.; Adya, V. B. (4 September 2019). "GWTC-1: A Gravitational-Wave Transient Catalog of Compact Binary Mergers Observed by LIGO and Virgo during the First and Second Observing Runs". Physical Review X. 9 (3): 031040. arXiv:1811.12907. Bibcode:2019PhRvX...9c1040A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.9.031040. ISSN 2160-3308. S2CID 119366083.

- ^ LIGO (1 November 2019). "Welcome to O3b!". @ligo. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ a b c "LIGO Suspends Third Observing Run (O3)". 26 March 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Gravitational-Wave Observatory Status". Gravitational Wave Open Science Center. 24 May 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ Castelvecchi, Davide (24 May 2023). "Gravitational-wave detector LIGO is back — and can now spot more colliding black holes than ever". Nature. 618 (7963): 13–14. Bibcode:2023Natur.618...13C. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-01732-4. PMID 37225822. S2CID 258899900.

- ^ "LIGO, VIRGO AND KAGRA OBSERVING RUN PLANS". Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Setting Priorities for Large Research Facility Projects Supported by the National Science Foundation. National Academies Press. 2004. pp. 109–117. Bibcode:2004splr.rept.....C. doi:10.17226/10895. ISBN 978-0-309-09084-1.

- ^ Gertsenshtein, M.E. (1962). "Wave Resonance of Light and Gravitational Waves". Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics. 14: 84.

- ^ Weiss, Rainer (1972). "Electromagnetically coupled broadband gravitational wave antenna". Quarterly Progress Report of the Research Laboratory of Electronics. 105 (54): 84. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ "A brief history of LIGO" (PDF). ligo.caltech.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ a b Buderi, Robert (19 September 1988). "Going after gravity: How a high-risk project got funded". The Scientist. 2 (17): 1. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ a b c Mervis, Jeffery. "Funding of two science labs receives pork barrel vs beer peer review debate". The Scientist. 5 (23). Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ a b Waldrop, M. Mitchell (7 September 1990). "Of politics, pulsars, death spirals – and LIGO". Science. 249 (4973): 1106–1108. Bibcode:1990Sci...249.1106W. doi:10.1126/science.249.4973.1106. PMID 17831979.

- ^ "Gravitational waves detected 100 years after Einstein's prediction" (PDF). LIGO. 11 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ Irion, Robert (21 April 2000). "LIGO's mission of gravity". Science. 288 (5465): 420–423. doi:10.1126/science.288.5465.420. S2CID 119020354.

- ^ a b c d "Interview with Barry Barish" (PDF). Shirley Cohen. Caltech. 1998. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ a b Cook, Victor (21 September 2001). NSF Management and Oversight of LIGO. Large Facility Projects Best Practices Workshop. NSF.

- ^ Travis, John (18 February 2016). "LIGO: A$250 million gamble". Science. 260 (5108): 612–614. Bibcode:1993Sci...260..612T. doi:10.1126/science.260.5108.612. PMID 17812204.

- ^ Anderson, Christopher (11 March 1994). "LIGO director out in shakeup". Science. 263 (5152): 1366. Bibcode:1994Sci...263.1366A. doi:10.1126/science.263.5152.1366. PMID 17776497.

- ^ Browne, Malcolm W. (30 April 1991). "Experts clash over project to detect gravity wave". New York Times. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ Anderson, Christopher (11 March 1994). "LIGO director out in shakeup". Science. 263 (5152): 1366. Bibcode:1994Sci...263.1366A. doi:10.1126/science.263.5152.1366. PMID 17776497.

- ^ Witze, Alexandra (16 July 2014), "Physics: Wave of the future", Nature, 511 (7509): 278–81, Bibcode:2014Natur.511..278W, doi:10.1038/511278a, PMID 25030149

- ^ "Gravitational wave detection a step closer with Advanced LIGO". SPIE Newsroom. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Daniel Sigg: The Advanced LIGO Detectors in the era of First Discoveries". SPIE Newsroom. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (11 February 2016). "Einstein's gravitational waves 'seen' from black holes". BBC News. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "Gravitational waves detected 100 years after Einstein's prediction". www.mpg.de. Max-Planck-Gelschaft. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ "LIGO Hanford's H1 Achieves Two-Hour Full Lock". February 2015. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015.

- ^ Zhang, Sarah (15 September 2015). "The Long Search for Elusive Ripples in Spacetime". Wired.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (19 September 2015). "Advanced Ligo: Labs 'open their ears' to the cosmos". BBC News. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ "Planning for a bright tomorrow: prospects for gravitational-wave astronomy with Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo". LIGO Scientific Collaboration. 23 December 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration, B. P. Abbott (11 February 2016). "Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger". Physical Review Letters. 116 (6): 061102. arXiv:1602.03837. Bibcode:2016PhRvL.116f1102A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102. PMID 26918975. S2CID 124959784.

- ^ a b c Castelvecchi, Davide; Witze, Witze (11 February 2016). "Einstein's gravitational waves found at last". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19361. S2CID 182916902. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ New results on the Search for Gravitational Waves. CERN Colloquium. 2016.

- ^ "Fundamental Physics Prize – News". Fundamental Physics Prize (2016). Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ a b Chu, Jennifer (15 June 2016). "For second time, LIGO detects gravitational waves". MIT News. MIT. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ B. P. Abbott; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration) (1 June 2017). "GW170104: Observation of a 50-Solar-Mass Binary Black Hole Coalescence at Redshift 0.2". Physical Review Letters. 118 (22): 221101. arXiv:1706.01812. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.118v1101A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.221101. PMID 28621973. S2CID 206291714.

- ^ Conover, E. (1 June 2017). "LIGO snags another set of gravitational waves". Science News. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ "College of Sciences Professor Appointed to Top Role in Search for Gravitational Waves | News Center".

- ^ "GW170814 : A three-detector observation of gravitational waves from a binary black hole coalescence". Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2017". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Rincon, Paul; Amos, Jonathan (3 October 2017). "Einstein's waves win Nobel Prize". BBC News. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (3 October 2017). "2017 Nobel Prize in Physics Awarded to LIGO Black Hole Researchers". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ "LSC News" (PDF).

- ^ Moore, Christopher; Cole, Robert; Berry, Christopher (19 July 2013). "Gravitational Wave Detectors and Sources". Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1993: Russell A. Hulse, Joseph H. Taylor Jr". nobelprize.org.

- ^ "Obituary: Dr. Robert L. Forward". www.spaceref.com. 21 September 2002. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ M.E. Gertsenshtein (1961). "Wave Resonance of Light and Gravitational Waves". JETP. 41 (1): 113–114. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ Gertsenshtein, M. E.; Pustovoit, V. I. (August 1962). "On the detection of low frequency gravitational waves". JETP. 43: 605–607.

- ^ Bonazzola, S; Marck, J A (1994). "Astrophysical Sources of Gravitational Radiation". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science. 44 (44): 655–717. Bibcode:1994ARNPS..44..655B. doi:10.1146/annurev.ns.44.120194.003255.

- ^ "Location of the Source". Gravitational Wave Astrophysics. University of Birmingham. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ "LIGO's Interferometer".

- ^ a b c Abbott, B.P.; et al. (2016). "Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger". Phys. Rev. Lett. 116 (6): 061102. arXiv:1602.03837. Bibcode:2016PhRvL.116f1102A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102. PMID 26918975. S2CID 124959784.

- ^ Thorne, Kip (2012). "Chapter 27.6: The Detection of Gravitational Waves (in "Applications of Classical Physics chapter 27: Gravitational Waves and Experimental Tests of General Relativity", Caltech lecture notes)" (PDF). Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "LIGO's Interferometer".

- ^ Doughton, Sandi (14 May 2018). "Suddenly there came a tapping: Ravens cause blips in massive physics instrument at Hanford". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ Abbott BP, Abbott R, Abbott TD, Acernese F, Ackley K, Adams C, et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration & Virgo Collaboration) (October 2017). "GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral". Physical Review Letters. 119 (16): 161101. arXiv:1710.05832. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119p1101A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.161101. PMID 29099225.

- ^ a b Pretorius, Frans (2005). "Evolution of Binary Black-Hole Spacetimes". Physical Review Letters. 95 (12): 121101. arXiv:gr-qc/0507014. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95l1101P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.121101. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 16197061. S2CID 24225193.

- ^ a b Campanelli, M.; Lousto, C.O.; Marronetti, P.; Zlochower, Y. (2006). "Accurate Evolutions of Orbiting Black-Hole Binaries without Excision". Physical Review Letters. 96 (11): 111101. arXiv:gr-qc/0511048. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..96k1101C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.111101. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 16605808. S2CID 5954627.

- ^ a b Baker, John G.; Centrella, Joan; Choi, Dae-Il; Koppitz, Michael; van Meter, James (2006). "Gravitational-Wave Extraction from an Inspiraling Configuration of Merging Black Holes". Physical Review Letters. 96 (11): 111102. arXiv:gr-qc/0511103. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..96k1102B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.111102. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 16605809. S2CID 23409406.

- ^ Svitil, Kathy (2 January 2008). "LIGO Sheds Light on Cosmic Event" (Press release). California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ Adhikari, Rana; Fritschel, Peter; Waldman, Sam (17 July 2006). Enhanced LIGO (PDF) (Technical report). LIGO-T060156-01-I.

- ^ Beckett, Dave (15 June 2009). "Firm Date Set for Start of S6". LIGO Laboratory News.

- ^ Danilishin, Stefan L.; Khalili, Farid Ya.; Miao, Haixing (29 April 2019). "Advanced quantum techniques for future gravitational-wave detectors". Living Reviews in Relativity. 22 (1): 2. arXiv:1903.05223. Bibcode:2019LRR....22....2D. doi:10.1007/s41114-019-0018-y. ISSN 2367-3613. S2CID 119238143.

- ^ Burtnyk, Kimberly (18 September 2015). "The Newest Search for Gravitational Waves has Begun". LIGO Scientific Collaboration. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

LIGO's advanced detectors are already three times more sensitive than Initial LIGO was by the end of its observational lifetime

- ^ Aasi, J (9 April 2015). "Advanced LIGO". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 32 (7): 074001. arXiv:1411.4547. Bibcode:2015CQGra..32g4001L. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/32/7/074001. S2CID 118570458.

- ^ Naeye, Robert (11 February 2016). "Gravitational Wave Detection Heralds New Era of Science". Sky and Telescope. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ Cho, Adrian (11 February 2016). "Here's the first person to spot those gravitational waves". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaf4039.

- ^ "Gravitational waves from black holes detected". BBC News. 11 February 2016.

- ^ Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; et al. (15 June 2016). "GW151226: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a 22 Solar-mass Binary Black Hole Coalescence". Physical Review Letters. 116 (24): 241103. arXiv:1606.04855. Bibcode:2016PhRvL.116x1103A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.241103. PMID 27367379. S2CID 118651851.

- ^ "VIRGO joins LIGO for the "Observation Run 2" (O2) data-taking period" (PDF). LIGO Scientific Collaboration & VIRGO collaboration. 1 August 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Update on the start of LIGO's 3rd observing run". 24 April 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

the start of O3 is currently projected to begin in early 2019. Updates will be provided once the installation phase is complete and the commissioning phase has begun. An update on the engineering run prior to O3 will be provided by late summer 2018.

- ^ Grant, Andrew (12 December 2016). "Advanced LIGO ramps up, with slight improvements". Physics Today. No. 11. doi:10.1063/PT.5.9074.

The bottom line is that [the sensitivity] is better than it was at the beginning of O1; we expect to get more detections.

- ^ GWTC-1: A Gravitational-Wave Transient Catalog of Compact Binary Mergers Observed by LIGO and Virgo during the First and Second Observing Runs

- ^ a b Chu, Jennifer (16 October 2017). "LIGO and Virgo make first detection of gravitational waves produced by colliding neutron stars" (Press release). LIGO.

- ^ "Gravitational waves from a binary black hole merger observed by LIGO and Virgo".

- ^ "LIGO and Virgo Detect Neutron Star Smash-Ups".

- ^ "Observatory Status". LIGO. 23 March 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Diego Bersanetti: Status of the Virgo gravitational-wave detector and the O3 Observing Run, EPS-HEP2019

- ^ "LIGO-Virgo network catches another neutron star collision".

- ^ "LIGO Laboratory statement on long term future observing plans". LIGO Lab. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Abbott, B. P.; et al. (24 November 2020). "Prospects for Observing and Localizing Gravitational-Wave Transients with Advanced LIGO, Advanced Virgo and KAGRA". Living Reviews in Relativity. 23 (1): 3. arXiv:1304.0670. doi:10.1007/s41114-020-00026-9. PMC 7520625. PMID 33015351.

- ^ "The future of gravitational wave astronomy" (PDF). Gravitational Waves International Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Fairhurst, Stephen (28 September 2012), "Improved Source Localization with LIGO India", Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 484 (1): 012007, arXiv:1205.6611, Bibcode:2014JPhCS.484a2007F, doi:10.1088/1742-6596/484/1/012007, S2CID 118583506, LIGO document P1200054-v6

- ^ Schutz, Bernard F. (25 April 2011), "Networks of Gravitational Wave Detectors and Three Figures of Merit", Classical and Quantum Gravity, 28 (12): 125023, arXiv:1102.5421, Bibcode:2011CQGra..28l5023S, doi:10.1088/0264-9381/28/12/125023, S2CID 119247573

- ^ Cho, Adrian (27 August 2010), "U.S. Physicists Eye Australia for New Site of Gravitational-Wave Detector" (PDF), Science, 329 (5995): 1003, Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1003C, doi:10.1126/science.329.5995.1003, PMID 20798288, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2013

- ^ Finn, Sam; Fritschel, Peter; Klimenko, Sergey; Raab, Fred; Sathyaprakash, B.; Saulson, Peter; Weiss, Rainer (13 May 2010), Report of the Committee to Compare the Scientific Cases for AHLV and HHLV, LIGO document T1000251-v1

- ^ U.S.-India Bilateral Cooperation on Science and Technology meeting fact sheet – dated 13 June 2012.

- ^ Memorandum to Members and Consultants of the National Science Board – dated 24 August 2012

- ^ Office of the Prime Minister of India [@PMOIndia] (17 February 2016). "Cabinet has granted 'in-principle' approval to the LIGO-India mega science proposal for research on gravitational waves" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "First LIGO Lab Outside US To Come Up In Maharashtra's Hingoli". NDTV. 8 September 2016.

- ^ Souradeep, Tarun (18 January 2019). "LIGO-India: Origins & site search" (PDF). p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "Cabinet clears Rs 2,600-crore LIGO-India; Observatory to come up in Maharashtra, will be part of global network". The Times of India. 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Upgraded LIGO to search for universe's most extreme events". www.nsf.gov. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Miller, John; Barsotti, Lisa; Vitale, Salvatore; Fritschel, Peter; Evans, Matthew; Sigg, Daniel (16 March 2015). "Prospects for doubling the range of Advanced LIGO" (PDF). Physical Review D. 91 (62005): 062005. arXiv:1410.5882. Bibcode:2015PhRvD..91f2005M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.91.062005. S2CID 18460400.

- ^ Zucker, Michael E. (7 July 2016). Getting an A+: Enhancing Advanced LIGO. LIGO–DAWN Workshop II. LIGO-G1601435-v3.

- ^ Thompson, Avery (15 February 2019). "LIGO Gravitational Wave Observatory Getting $30 Million Upgrade". www.popularmechanics.com. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (15 February 2019). "Black hole detectors to get big upgrade". Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "LIGO-T1800042-v5: The A+ design curve". dcc.ligo.org. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "The Quantum Enhanced LIGO Detector Sets New Sensitivity Record".

- ^ Tse, M.; Yu, Haocun; Kijbunchoo, N.; Fernandez-Galiana, A.; Dupej, P.; Barsotti, L.; Blair, C. D.; Brown, D. D.; Dwyer, S. E.; Effler, A.; Evans, M. (5 December 2019). "Quantum-Enhanced Advanced LIGO Detectors in the Era of Gravitational-Wave Astronomy". Physical Review Letters. 123 (23): 231107. Bibcode:2019PhRvL.123w1107T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.231107. hdl:1721.1/136579.2. PMID 31868462.

- ^ a b McClelland, David; Evans, Matthew; Lantz, Brian; Martin, Ian; Quetschke, Volker; Schnabel, Roman (8 October 2015). Instrument Science White Paper (Report). LIGO Scientific Collaboration. LIGO Document T1500290-v2.

- ^ LIGO Scientific Collaboration (10 February 2015). Instrument Science White Paper (PDF) (Technical report). LIGO. LIGO-T1400316-v4. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

References

[edit]- Kip Thorne, ITP & Caltech. Spacetime Warps and the Quantum: A Glimpse of the Future. Lecture slides and audio

- Barry C. Barish, Caltech. The Detection of Gravitational Waves. Video from CERN Academic Training Lectures, 1996

- Barry C. Barish, Caltech. Einstein's Unfinished Symphony: Sounds from the Distant Universe Video from IHMC Florida Institute for Human Machine Cognition 2004 Evening Lecture Series.

- Rainer Weiss, Electromagnetically coupled broad-band gravitational wave antenna, MIT RLE QPR 1972

- On the detection of low frequency gravitational waves, M.E. Gertsenshtein and V.I. Pustovoit – JETP Vol. 43 pp. 605–607 (August 1962) Note: This is the first paper proposing the use of interferometers for the detection of gravitational waves.

- Wave resonance of light and gravitational waves – M.E. Gertsenshtein – JETP Vol. 41 pp. 113–114 (July 1961)

- Gravitational electromagnetic resonance, V.B. Braginskii, M.B. Mensky – GR.G. Vol. 3 No. 4 pp. 401–402 (1972)

- Gravitational radiation and the prospect of its experimental discovery, V.B. Braginsky – Usp. Fiz. Nauk Vol. 86 pp. 433–446 (July 1965). English translation: Sov. Phys. Uspekhi Vol. 8 No. 4 pp. 513–521 (1966)

- On the electromagnetic detection of gravitational waves, V.B. Braginsky, L.P. Grishchuck, A.G. Dooshkevieh, M.B. Mensky, I.D. Novikov, M.V. Sazhin and Y.B. Zeldovisch – GR.G. Vol. 11 No. 6 pp. 407–408 (1979)

- On the propagation of electromagnetic radiation in the field of a plane gravitational wave, E. Montanari – gr-qc/9806054 (11 June 1998)

Further reading

[edit]- Barish, Barry C. (2000). "The Science and Detection of Gravitational Waves" (PDF).

- Bartusiak, Marcia (2000). Einstein's unfinished symphony : listening to the sounds of space-time. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 978-0-425-18620-6.

- Saulson, Peter (1994). Fundamentals of interferometric gravitational wave detectors. Singapore River Edge, NJ: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-1820-1.

- Collins, Harry M. (2004). Gravity's shadow the search for gravitational waves. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-11378-4.

- Kennefick, Daniel (2007). Traveling at the speed of thought : Einstein and the quest for gravitational waves. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11727-0.

- Janna Levin (2016). Black hole blues : and other songs from outer space. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0307958198

- Collins, Harry, M. (2017). Gravity's kiss: the detection of gravitational waves. Cambridge, MA & London: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03618-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- LIGO Newsletters Excellent wide-audience newsletters published twice-yearly in March and September. From Issue 1 (September 2012) through to present day.

- LIGO Scientific Collaboration web page

- LIGO outreach webpage, with links to summaries of the Collaboration's scientific articles, written for a general public audience

- LIGO Laboratory

- LIGO News blog

- Living LIGO blog: answering questions about LIGO science and being a scientist by LIGO member Amber Stuver

- Advanced LIGO homepage

- Columbia Experimental Gravity

- American Museum of Natural History film and other materials on LIGO

- 40 m Prototype

- Earth-Motion studies A brief discussion of efforts to correct for seismic and human-related activity that contributes to the background signal of the LIGO detectors.

- Caltech's Physics 237-2002 Gravitational Waves by Kip Thorne Video plus notes: Graduate level but does not assume knowledge of General Relativity, Tensor Analysis, or Differential Geometry; Part 1: Theory (10 lectures), Part 2: Detection (9 lectures)

- Caltech Tutorial on Relativity – An extensive description of gravitational waves and their sources.

- Q&A: Rainer Weiss on LIGO's origins at news.mit.edu

- LIGO: a strong belief, 2/11/16 CERN Courier Interview with Barry Barish (18 March 2016 publication date).

- Video (3:10): LIGO Orrey (1 December 2018) on YouTube