L'Homme truqué (The Doctored Man)

Cover drawn by Maurice de Becque of the collection L'Homme truqué published in 1921 by éditions G. Crès. | |

| Author | Maurice Renard |

|---|---|

| Original title | L'Homme truqué |

| Genre | Science-fiction Scientific-marvel |

| Publisher | Je sais tout |

Publication date | March 1921 |

| Publication place | France |

L'Homme truqué is a short novel by Maurice Renard, initially published in March 1921 in the magazine Je sais tout. Regularly republished in France during the 20th and 21st centuries, it also benefits from numerous publications abroad.

Maurice Renard tells the story of Jean Lebris, a soldier who lost his sight during the trench war, returning to his home town. Having acquired superhuman vision following a medical experiment aimed at restoring his sight, he tries to hide his cumbersome secret from those around him.

Written in the aftermath of the First World War, the novel features a war cripple. It appears as a pessimistic work, both by its theme - the difficult rehabilitation of a disabled soldier - and by its tragic ending. As such, it bears witness to the trauma suffered by the French population in the aftermath of the war.

At the same time, Maurice Renard, leader of the scientific-marvel literary genre, seeks with this tale of scientific imagination to give the reader food for thought. He pushes the latter to question the scientific progress on which he occasionally offers a nuanced look, notably through the question of the superhuman, but also on the existence of the invisible worlds that surround us.

In 2013, writer Serge Lehman and cartoonist Gess revisited this classic of the scientific-marvel genre in a homonymous comic book, transposing the character created by Maurice Renard into a superheroic context.

Origin of the work

[edit]Maurice Renard, cantor of scientific-marvel

[edit]

Maurice Renard is a novelist of the scientific imagination who seeks to theorize a literary genre under the name of "scientific-marvel"[Note 1] novel to promote its emergence. Author of the successful Le Docteur Lerne, sous-dieu (1908) and Le Péril bleu (1911), he assigned in a founding article published in 1909 considerable aspirations to the literary genre, namely to give the reader food for thought through the application of scientific methods to irrational events.[1] During the first quarter of the 20th century, the writer tries to make his readers think about the effects of progress.[2] Thus, Maurice Renard advocates the use of science, no longer as a setting like the scientific novels of Jules Verne, but as a disruptive element that generates a wonderful phenomenon.[3]

The war suspended his literary activities, as he was mobilized between August 1914 and January 1919.[4] After the war, his financial problems forced him to devote himself to a more popular literature genre. He then produced hybrid texts in which the police and love plots took precedence over the scientific-marvel dimension.[5]

When defining the scientific-marvel, Maurice Renard explicitly refers to the works of several novelists he admires, including the French-Belgian J.-H. Rosny aîné and the Englishman H. G. Wells.[6] Thus, the novel[Note 2] L'Homme truqué is inspired by the work of these two authors, namely the stories Un autre monde by Rosny aîné and Un étrange phénomène by Wells, two works published in 1895 that deal with individuals handicapped by their fantastic vision.[7] In addition to literary works, he probably also drew his inspiration from the invention of radiography. In November 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen took the first photographs of his wife's hand, in which the bones appear clearly surrounded by the lighter halo of the flesh. Maurice Renard transposes this process to a vision of the electrical phenomena with which the main character is provided, who manages to see a tree-like image of the nervous tissue of individuals.[8]

A creative context marked by war

[edit]

If the rapid development of science and technology in the late 19th century produced optimistic works by novelists of scientific imagination, at the same time a number of novels were concerned with the social danger that science could represent. The First World War and the trauma induced by the devastation caused by technology reinforces in these novelists this mistrust of science,[9] especially with the proliferation of mad scientists in fictional stories.[10]

Besides this nuanced look at science and its potential, the figure of the soldier transformed by war, whether physically or psychically, is a theme that appears from the beginning of the conflict. Thus, J.-H. Rosny aîné, in his novel L'Énigme de Givreuse published in 1916, presents a wounded soldier returning from the front line after having been split into two completely identical copies. In this story, which is not about war but about its consequences, Rosny Aîné questions scientific research and its own limits.[11] This theme, also important for Maurice Renard, appeared as early as 1920 with the short story La Rumeur dans la montagne, which featured a painter traumatized by the war.[12] The following year, he published the novel L'Homme truqué which, like L'Énigme de Givreuse, deals with a soldier returning home after having undergone a physical transformation caused by scientists.[9]

The story

[edit]Abstract

[edit]Prologue and Epilogue

[edit]In the post-war years, the constables of Belvoux, Mochon and Juliaz, discover in the woods, the corpse of Doctor Bare, shot in the head. The constables go to the victim's house and discover that his home has been completely searched. They nevertheless find a manuscript written by the doctor that had escaped the vigilance of the criminals. This document forms a narrative of which the bloody death of the doctor is only the epilogue.

The revealing gesture

[edit]

Dr. Bare's manuscript begins with his reunion with Jean Lebris, who had been presumed dead for France in June 1918. The latter tells the doctor that after a battle during which he lost his sight, he was taken by Germans to a doctor experimenting a new ophthalmological treatment. It is by taking advantage of the discontent of his jailer that he was able to escape and return to his home town. As Jean returned to his mother's house, Dr. Bare observed him through the window and witnessed an incredible scene that made him doubt the young man's real blindness: at the last stroke of noon, he looked at his watch and set it back on time.

Jean Lebris' adventure

[edit]A couple of weeks later, while the doctor is examining Jean for his worsening cough, he meets Madame Lebris' new tenant, a young girl named Fanny, and is immediately seduced. The doctor finally learns Jean's secret, when he surprises him in the woods: surprised, the young man turns around and points his gun at the doctor hidden behind a bush. Learning that the doctor is his friend Dr. Bare, Jean sets out to tell him the truth. He reveals to her that after being wounded in the battle of Dormans, German soldiers have taken him to a clinic in a forest in central Europe. Blinded, he was treated by Dr. Prosope, who removed his eyes and replaced them with new ones. When he wakes up from the operation, Jean manages to see a being of light in front of him despite the blindfold on his new eyes. Doctor Prosope explains to him the principle of his new vision: for a normal person, the eye is connected to the brain by the optic nerve, which transmits to the brain the light impressions that the eye has received. By replacing John's eyes with organs that allow him to see electricity, electroscopes, he can see the nervous system of people, even through walls. Following the argument of Doctor Prosope with his servant, the latter secretly leaves the clinic taking Jean with him. He takes him to Strasbourg where Jean can first join his military hierarchy, before returning to his home town.

Radiography

[edit]In the weeks following Fanny's arrival in Belvoux, the young girl and Dr. Bare become so close that Dr. Bare finally confesses his feelings for her and asks for her hand in marriage. Fanny refuses on the grounds that the news would break Jean's heart, in whom she guesses to have feelings identical to those of the doctor. She replies that she will accept in two months when Jean, who is very ill, will be dead. After Jean agrees to be x-rayed by the doctor, the hospice housing the laboratory is the prey of a fire. Dr. Bare then suspects that Prosope was involved in destroying the evidence of Jean's electroscopes.

The last days of the phenomenon

[edit]Increasingly ill, John suffers a violent attack accompanied by hemoptysis that leaves him bedridden. During his enforced rest, Jean's well-developed sixth sense can distinguish unsuspected forms of electricity moving through the air, which could be an invisible race, made up exclusively of electricity, surrounding us. His condition worsens and Jean eventually dies. The doctor then tells Fanny about the electromagnetic eyes and his plan to prevent anyone from stealing the eyes of the corpse. Having left to instruct the masons to make his grave impossible to break into, the doctor leaves Fanny at Jean's bedside before replacing her at nightfall. At night, when he hopes to steal the electroscopic eyes, he discovers that they have disappeared. In the morning, going to Fanny to tell her about his disappointment, he discovers that she has also disappeared and deduces that she has manipulated him since their meeting. The doctor tries to reassure himself by saying to himself that she had to love him a little to have allowed him to remain alive.

Main characters

[edit]

The main character of this novel is Jean Lebris. This soldier, who disappeared during the war, reappears after the conflict in his home town. Blinded by a shell explosion in the trenches, he is rescued by a German ambulance before being handed over to mysterious doctors. At his own expense, he becomes the subject of a medical experiment to restore his sight. Having recovered his sight thanks to the installation of electroscopes allowing him to see electricity, he managed to flee and reach his village of Belvoux. Feeling in danger, he hides his increased vision from those around him.[13]

This secret is nevertheless discovered by his friend Dr. Bare, who takes care of his declining health. As the narrator of the story, he is the confidant of Jean Lebris' revelations. His love for the beautiful Fanny Grive also blinds him and prevents him from protecting his friend's secret. Indeed, the young woman arrives with her mother some time after Lebris' return to Belvoux. Becoming very quickly friends with Bare and Lebris, she manages to manipulate the doctor to recover the electroscopes for the account of Doctor Prosope. This medical genius, of unknown nationality, is at the origin of Jean Lebris' transplanted eyes.[13] A mysterious scientist whose secrets are never revealed, he owns a clinic in the heart of central Europe, where he experiments his inventions on wounded soldiers.[Note 3] After seeing his invention escape him, and although he only appears in Lebris' memories, his shadow hangs over the whole story.

Critical review

[edit]If the novel appears retrospectively as a major work of the scientific-marvel genre - the science-fiction essayist Jacques Van Herp praises in 1956 the dramatic force of the work of Maurice Renard as "a long lucid nightmare" that the author manages to carry out with mastery, the essayist Pierre Versins admires in 1972 a nightmarish tale marked by "a strange visual poetry", while the two essayists Guy Costes and Joseph Altairac qualify in 2018 the novel as "one of the most poignant texts of Maurice Renard" -, from its publication, the contemporary critics of L'Homme truqué welcome, on the whole, a successful although fanciful story.

The novelist Renée Dunan - also an author of scientific-marvel novels - admires Maurice Renard's ability to tell the story of a man who sees a world inaccessible to his fellow men. Indeed, conquered by the literary qualities of the work, she recommended to award the writer the Goncourt Prize.[14]

The power of imagination of Maurice Renard is praised in the Journal de l'Association médicale mutuelle of October 1922. The journalist and doctor Raymond Nogué qualifies the story as a scientific novel of quality which manages to captivate the reader on the exceptional faculties of the hero, in spite of a somewhat fanciful treatment.[15]

This glowing review was qualified by Charles Bourdon, contributor to the journal Romans-revue: guide de lectures. In an article published on May 15, 1922, if he also classifies the novel in the line of the works of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells by the scientific content of the story, even if this one pours in the fantastic, he nevertheless deplores a "literary value [...] not appreciably exceeding the average". This magazine, whose editor-in-chief is Abbot Bethlehem, a true promoter of Catholic censorship in France,[16] gives Maurice Renard credit for producing at least a captivating story that does not offend decency.[17]

Finally, the journalist Jean de Pierrefeu regrets that the novelistic intentions of the writer are detrimental to the scientific content of the story. Thus, in an article in the Journal des débats politiques et littéraires of January 25, 1922, he deplores, in addition to a lack of originality with respect to H. G. Wells, that the dramatic power of the novel makes it fall into what he pejoratively qualifies as a soap opera.[18]

The topics covered

[edit]L'Homme truqué, a "broken face"

[edit]

Maurice Renard's novel deals with the return of a wounded soldier to his home town after the war. Indeed, Jean Lebris lost his sight after a shell exploded a few meters away from him. He then undergoes a surgery allowing him to recover his sight.

Published in 1921, his character appeared in the context of the post-war period when many survivors returned home severely handicapped by wounds, particularly to the face.[Note 4] Referred to as "broken faces",[8] these soldiers became the symbol of war for all those who denounced its horrors. They also testify to the trauma caused when the soldiers returned from the trenches to the civilian population. The "broken faces" show an aspect of the war that the propaganda not only does not talk about, but above all fails to hide. They become the disfigured face of a wounded country, and their deformity sets them apart from society. In addition to the reference to the wounded nation, the face of the disfigured soldier inspires the novelists who make it a metaphor for Europe in reconstruction.[9]

Thus, after his wound on the battlefield, Jean Lebris arrives in the hands of the archetypal mad scientist: Doctor Prosope, of unknown nationality.[19] He gives him back his sight by replacing his eyes with electroscopes. Indeed, this scientist has developed an artificial eye that records electricity. In this respect, L'Homme truqué bears witness to this post-war period when an unprecedented need for reconstructive surgery appeared in France and which pushed the latter to solve complex cases and to progress.[19]

A superhuman born in the trenches: scientific wonder at work

[edit]The First World War was such a deadly conflict that it caused a real trauma among the population. Indeed, it is in this context that the terms " superhuman " and " superheroes " are used more and more frequently in Europe as well as in the United States to qualify the heroes who distinguish themselves in this extraordinary conflict.[19] Promoter of the scientific-marvel genre, which aims to give a new point of view on the potentialities of science, Maurice Renard makes an analogy, in the plot of L'Homme truqué, between this new look and the superhuman vision of the character.[20]

Following his surgery, Jean Lebris gains an extraordinary vision, which allows him to discern things like people's nervous systems and heat sources, especially in the dark or through walls. Through the genius doctor Prosope, Maurice Renard proposes a phantasmagorical explanation to justify the sixth sense acquired by Jean Lebris: the electroscopes make it possible to capture electricity, in the same way that ears grafted in place of the eyes would have made it possible to see sounds.[21] Endowed with his extraordinary vision, Jean Lebris describes an environment bathed in an electric field, whose slightest anomaly, the smallest variation reflects a particular hue.[22] This gift, extremely powerful even for his eyelids, obliges him to wear special glasses that block his vision. The electric implant graft, far from being an ocular repair, is really conceived as a transhumanist augmentation. Indeed, his augmented vision even allows him to observe strange creatures made of electricity, living unbeknownst to the common man,[7] like the Sarvants, the invisible spiders that Maurice Renard portrays in his 1911 novel Le Péril bleu[Note 5][12]. In L'Homme truqué, this invisible life form exists in the immediate environment of human beings in the form of orbs. The common mortal, not possessing sensory organs sensitive enough to perceive them, is unaware of the very existence of these electric beings.[23]

However, if Jean Lebris is indeed a superhuman made by the war, he is not a superhero.[Note 6] Moreover, he gradually becomes aware of his role as a guinea pig, so much so that, refusing his new status of superhuman, he wishes to return to his home town to live his former life.[22] So, after having escaped from Doctor Prosope and joined Belvoux, the young man tries to hide his exceptional vision from those around him. Only his friend, Doctor Bare, discovers the truth but, powerless, cannot prevent his slow death caused by serious health problems.

Apart from some apparent similarities, Jean Lebris does not have the usual superhero characteristics. First of all, he does not transform himself into a vigilante, nor does he confront Prosope in a spectacular fight. Nor does he have a pseudonym, since the name "L'Homme truqué" is only the title of the novel, but is not used again in the body of the text.[24] Moreover, this name, which means the will to deceive by diverting something from its primary function, illustrates all the ambiguity of his superhuman status.[22] Lebris dies in the space of a few pages and Bare himself is murdered without managing to prevent the agents of Prosope from recovering the famous prostheses. Without ever appearing as a superhero, Jean Lebris is the hero of a pessimistic novel where the sense of justice is totally absent.[24]

A nuanced view of progress

[edit]

With this short novel, Maurice Renard, far from singing the praises of an extraordinary medical experiment, takes a nuanced look at scientific progress. He illustrates one of the inclinations of the scientific-marvel novel, that is to say, to put in narrative the scientific conjecture in order to propose to the reader another possible world.[25] The main character reveals his realization that he is only the guinea pig of a doctor who has stripped him of his identity. His return to his native village is only a temporary shelter before the return of Doctor Prosope who has come to protect the secret of his formidable invention.[21] And if he is the object of all the attention of the scientist, it is only because he is the only one to have revealed positive results.[22] The concern generated by the transhumanist novelty is also expressed through the character of Dr. Bare, confidant and doctor of Jean Lebris, who is surprised during the auscultation, that the use of a fixed ocular apparatus does not cause strong inflammation.[26]

In the course of the story, Jean Lebris reveals that the laboratory, located in the heart of Europe, is staffed by people of many different nationalities, speaking an invented language. Maurice Renard describes here a secret society living in a scientific counter-utopia on the fringe of the world, which aims, despite methods ranging from kidnapping to murder, at an improvement of the human race.[21] If he does recover the vision, it is not for his personal interest, but in the service of an amoral science, for which he appears only as the instrument of an occult power devoid of any empathy.[22]

Narrative procedures

[edit]In his works in general, Maurice Renard combines the marvelous, the supernatural, the anticipation and the police mystery.[27] This short novel also testifies to this hybridization of genres, insofar as it closely associates the narrative dynamics of the police investigation with the principle of the marvelous-scientific genre, which is the exploration of the consequences that flow from scientific innovations.[28]

L'Homme truqué uses a narrative structure close to that of popular novels. Indeed, it is built around a setting identical to that of detective novels: the prologue narrates the discovery by constables of a murder and of a letter written by the victim, which constitutes the body of the novel. This letter, left to the discretion of the readers, was supposed to accompany a scientific document taken by the murderers, which is, in all likelihood, the motive for the murder.[29] Maurice Renard uses this process of embedded and retrospective narrative to announce the fate of the characters from the beginning of the novel.[13] Thus, after the prologue, the novel takes the form of a narrative narrated in the first person by the main character's doctor.[30] Maurice Renard plays with irony here by contrasting the prologue, which establishes the narrator's death, with the excipit of the narrative, in which the latter congratulates himself on still being alive, spared by the spy with whom he had fallen in love.[28]

Although the story is related to the scientific-marvel genre, through the scientific explanation of a mystery of supernatural appearance, it is above all presented as a detective story, whose stake is not so much its resolution as its unveiling.[13] It is constructed as an investigation on two levels: on one hand, the story must shed light on the reasons for the narrator's murder, and on the other hand, it is constructed through the investigation of the doctor who seeks to pierce the secrets of his friend Jean Lebris and his extraordinary faculties. Maurice Renard uses the principle of cascading revelations in order to give consistency to the marvelous and to incite, by training the reader to adhere to its purpose. This narrative strategy, which consists in bringing the reader to wonder about the consequences of the scientific progress through what he calls "the imminent threat of the possible",[31] corresponds moreover completely to his literary project that he announces in his manifesto of 1909 "Of the marvelous-scientific novel and its action on the intelligence of progress".[28] This balance between the comic, fantastic, detective and marvelous-scientific aspects that the author seeks to establish, aims to make the speculative assumptions of the story acceptable to the reader.[32]

A representation of scientific marvel: the illustrations of L'Homme truqué

[edit]

"Jean had just opened his eyes, and I was all in my surprise. Ah! those eyes!... Let us imagine an animated ancient statue; let us imagine a beautiful marble head raising its eyelids on the plain globe of its eyes without slits..."

— Maurice Renard

In the first editions of the novel, the text is accompanied by illustrations through which the artists wonder how to represent a "blind man who sees". The fusion of man and technological apparatus is confusing for these artists, who struggle to represent the mysterious electroscopes other than through the empty eyes of the hero.[33] Thus, in March 1921, Alexandre Rzewuski, a worldly painter of the Roaring Twenties, illustrates the novel in the magazine Je sais tout while bringing a real artistic added value to the story.[34] The artist represents the empty eye sockets of Jean Lebris in which a white enamel device is lodged. The expression of the face and the depth of the features nevertheless suggest a clairvoyance in the young man.[35]

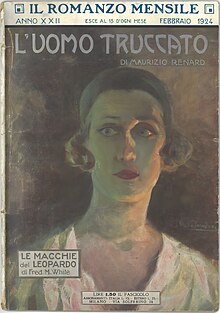

His eyelids being ineffective to protect him from his electromagnetic visions, Prosope makes him a pair of glasses to allow his eyes to rest. His representation is also the subject of reflection by the designers. Thus, while Alexander Rzewuski was inspired by the gas masks and goggles used by soldiers on the front line to give him an avant-garde look, the Milanese designer of the Italian version of 1924, Riccardo Salvadori, opted for glasses without arms that are fixed directly on his eyes.[33]

When the collection was released in bookstores, Louis Bailly illustrated the cover. It represents Jean Lebris holding a blind man's cane in the middle of luminous orbs floating around him. These circles could be inspired both by the photographs of Dr. Hippolyte Baraduc, who seeks to reveal through images the alleged odic force released by living beings, and by the research of physiologists in the 1880s on subjective vision, that is to say, on the ability of individuals to perceive luminous phenomena that do not exist in reality. In this particular case, the colored bubbles drawn by Louis Bailly would be similar to a phenomenon of subjective sensation of light, such as retinal persistence or the production of luminous images when the retina is hit. However, except on the cover, Louis Bailly does not represent the extraordinary vision of the hero in his interior illustrations.[35]

French editions and distribution abroad

[edit]Published in France

[edit]The success of L'Homme truqué allowed it to be published three times in the span of two years. First of all, Maurice Renard published his novel in the magazine directed by Pierre Lafitte, Je sais tout no 183 of March 15, 1921. This text is illustrated by the drawings of Alexandre Rzewuski. The same year, it was published in hardback, with two other short stories by the author, by Éditions Georges Crès. It was published in the "Collection littéraire des romans d'aventures" under the title L'Homme truqué, followed by Château hanté and La Rumeur dans la montagne. Pierre Laffite finally publishes the novel in 1923 in bound format in his collection "Idéal-bibliothèque" No. 16, which he hires the services of Louis Bailly for the cover and interior illustrations.[36]

In 1958, Éditions Tallandier published the novel in the collection L'Homme truqué, followed by Un homme chez les microbes,[37] while Éditions Robert Laffont published it in 1989 in its collection "Bouquins" alongside many other stories of the writer in the collection Maurice Renard, Romans et contes fantastiques. Finally, the novel - which fell into the public domain in 2010 - was published by L'Arbre vengeur in 2014.[36]

Foreign language broadcasting

[edit]

In the course of the 20th century, L'Homme truqué was translated into several languages for distribution outside France. Thus, the novel was quickly translated into Italian under the title L'uomo truccato and published in 1924 in the periodical Il Romanzo Mensile. The cartoonist Riccardo Salvadori was asked to illustrate the story.[3]

A Spanish version, El enigma de los ojos misteriosos, was published in 1935 in the magazine Emoción, no. 51 and no. 52, and was illustrated by Alfonso Tirado. Also in a magazine, the novel was translated by Ion Hobana into Romanian: Omul trucat appeared in 1968. After this publication in No. 336, No. 337 and No. 338 of Povestiri științifico-fantastice, it was again reissued by Labirint in 1991.[38]

While a Russian version, Taïna iego glaz, illustrated by D.S. Lebedikhin, was published by Start Editions in 1991, the novel was finally translated into English in 2010 by Brian Stableford under the title The Doctored Man. Published by Black Coat Press, it is illustrated by Gilles Francescano.[38]

Adaptations

[edit]The novel was adapted for the first time for radio in 1981 by Marguerite Cassan. Directed by Claude Roland-Manuel as a radio drama in five episodes, the recording was broadcast on France Culture on November 16, 1981.[39]

In 2013, Serge Lehman made - together with the cartoonist Gess - a free adaptation of this story in a comic book of the same name. This work is integrated into the universe of La Brigade chimérique, a comic book series published by both authors between 2009 and 2010, which explores the disappearance of supermen in the aftermath of World War II. Thus, the story of this "doctored man" is revisited and made more optimistic than the original, as it is explained that Maurice Renard lied to protect the existence of the real Jean Lebris. Transposed into a superheroic context, Lebris appears alongside his creator Maurice Renard - who is presented as his official biographer - and many other fictional heroes of early 20th century popular literature.[24] In 2022, Serge Lehman reuses the character of Jean Lebris for new adventures. He tells how he took refuge in the United States on the eve of the Second World War and started a career as a superhero - one of his adventures was even illustrated by Jack Kirby -, before returning to France in 2021 to join the new Chimeric Brigade.[40]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In 1909, he appropriated the expression "scientific-marvel", used by critics to designate scientific novels as a whole, to which he added a hyphen. This typographical addition also transformed the expression into an adjective.

- ^ This short novel is sometimes called a short story

- ^ Jean Lebris detects, thanks to his augmented vision, eleven other patients present in the clinic of Doctor Prosope.

- ^ Among the French wounded in the First World War, 14% were hit in the face.

- ^ In his adaptation of the novel into a comic book, Serge Lehman mixes the race of the Sarvants with the threats that Jean Lebris faces.

- ^ The protagonist of The Rigged Man nevertheless evokes, in many ways, the character of Daredevil, an American superhero, created by Stan Lee and Bill Everett in April 1964, who sees his senses become very sharp after becoming blind.

References

[edit]Original edition

[edit]- Maurice Renard (March 15, 1921). "L'Homme truqué". Je sais tout (in French). Paris: 315–360. Renard1921.

Secondary sources of information

[edit]- ^ Bréan (2018, § 1)

- ^ Bréan (2018, § 21)

- ^ a b Fleur Hopkins (April 30, 2019). "Le merveilleux scientifique: une Atlantide littéraire". Le blog Gallica.

- ^ Jean Cabanel. "Maurice Renard". Triptyque (in French) (24): 8.

- ^ Fleur Hopkins (2018). "Écrire un « conte à structure savante » : apparition, métamorphoses et déclin du récit merveilleux-scientifique dans l'œuvre de Maurice Renard (1909-1931)". ReS Futurae (in French). 11: § 43.

- ^ Fleur Hopkins; Jean-Guillaume Lanuque (dir.) (2018). "Généalogie et postérité du genre merveilleux-scientifique (1875-2017): apparitions, déformations et complexités d'une expression". Dimension Merveilleux scientifique 4. Encino (Calif.): Black Coat Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-61227-749-3.

- ^ a b Evans (2018, § 15)

- ^ a b Goffette (2017, p. 9)

- ^ a b c Hummel (2018, p. 81)

- ^ Roger Musnik (June 4, 2019). "De Jules Verne à Maurice Renard: les précurseurs". Le blog Gallica (in French).

- ^ Costes & Altairac (2018, p. 1818)

- ^ a b Costes & Altairac (2018, p. 1715)

- ^ a b c d Hummel (2018, p. 85)

- ^ Renée Dunan (July 25, 1921). "Prix littéraires". La Pensée française (in French): 11.

- ^ Raymond Nogué (October 1922). "Revue bibliographique". Journal de l'Association médicale mutuelle (in French): 210.

- ^ Cyril Piroux (May 9, 2013). "Aux Abois de Tristan Bernard. Genèse d'une écriture de l'absurde". Fabula: § 34.

- ^ Charles Bourdon (May 15, 1922). "Les Romans". Romans-revue: Guide de Lectures (in French): 366–367.

- ^ Jean de Pierrefeu (January 25, 1922). "Romans d'imaginations, romans scientifiques". Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (in French): 3.

- ^ a b c Fournier (2014, p. 90)

- ^ Hopkins & Goffette (2019, p. 251)

- ^ a b c Hummel (2018, p. 86)

- ^ a b c d e Boutel

- ^ Hopkins & Goffette (2019, p. 261)

- ^ a b c Fournier (2014, p. 91)

- ^ Hummel (2018, p. 87)

- ^ Hopkins & Goffette (2019, p. 260)

- ^ Jean-Baptiste Baronian. Panorama de la littérature fantastique de langue française (in French). Paris: Stock. p. 176. ISBN 978-2-234-00902-8. Baronian1978.

- ^ a b c Bréan (2018, § 17)

- ^ Hummel (2018, p. 84)

- ^ Evans (2018, § 16)

- ^ Maurice Renard (October 1909). "Du roman merveilleux-scientifique et de son action sur l'intelligence du progrès". Le Spectateur (in French) (6): § 14.

- ^ Bréan (2018, § 20)

- ^ a b Hopkins & Goffette (2019, p. 263)

- ^ Delphine Gleizes (October 30, 2018). "" Ceci n'est point un titre inventé à plaisir… "". COnTEXTES (in French): § 31.

- ^ a b Hopkins & Goffette (2019, p. 262)

- ^ a b Costes & Altairac (2018, p. 1717)

- ^ "Notice bibliographique de L'Homme truqué, suivi de: Un Homme chez les microbes". Bibliothèque nationale de France (in French).

- ^ a b "L'homme truqué". The Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ "Notice BnF n°FRBNF40898255". BnF – Catalogue général (in French). Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Nicolas Martin; Serge Lehman; Stéphane De Caneva (February 11, 2022). "La brigade chimérique: nos héros ont du talent". France Culture (in French).

Appendices

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Boutel, Jean-Luc. "L'Homme truqué". Sur l'autre face du monde (in French). Boutel.

- Bréan, Simon (2018). "L'écriture de Maurice Renard, en tension entre extrapolation scientifique et figuration littéraire". ReS Futurae (in French) (11).

- Costes, Guy; Altairac, Joseph (2018). Rétrofictions : encyclopédie de la conjecture romanesque rationnelle francophone, de Rabelais à Barjavel, 1532-1951 (in French). Amiens / Paris: Maison d'édition Encrage / Les Belles Lettres. p. 2458. ISBN 978-2-251-44851-0. CostesAltairac2018.

- Evans, Arthur B. (2018). "La science-fiction fantastique de Maurice Renard". ReS Futurae (in French) (11).

- Fournier, Xavier (2014). Super-héros. Une histoire française (in French). Paris: HuginnMuninn. p. 2458. ISBN 978-2-36480-127-1. Fournier2014.

- Goffette, Jérôme (2017). Deux études du corps dans la science-fiction (in French). Paris: Books on Demand. p. 44. ISBN 978-2-322-13815-9. Goffette2017.

- Gouanvic, Jean-Marc (1994). La science-fiction française au 20è siècle (1900-1968) : essai de socio-poétique d'un genre en émergence (in French). Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 292. ISBN 978-90-5183-775-9.

- Hopkins, Fleur; Goffette, Jérôme (2019). Science-fiction, prothèses et cyborgs (in French). Books on Demand. pp. 251–270. Hopkins2019.

- Hummel, Clément (December 2018). "Les Gueules cassées du merveilleux scientifique: L'Énigme de Givreuse de J.-H. Rosny aîné et L'Homme truqué de Maurice Renard". Galaxies (in French) (56/98): 81–87. ISBN 978-2-37625-060-9.

- Versins, Pierre (1984). Encyclopédie de l'utopie, des voyages extraordinaires et de la science-fiction (in French). Lausanne: Éditions L' ge d'Homme. p. 1042. ISBN 978-2-8251-2965-4.

Related articles

[edit]External links

[edit]- Resources for literature: NooSFere • Internet Speculative Fiction Database