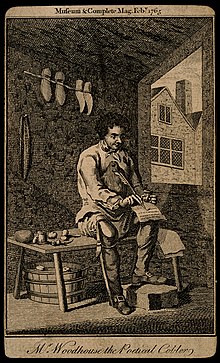

James Woodhouse (poet)

James Woodhouse (1735–1820) was an English poet from the Black Country village of Rowley Regis. He was known as the "shoe-maker poet" from his trade that supported him during his early years. He made the acquaintance of the poet William Shenstone, who lived nearby, and was encouraged by him to write poetry. In 1764 a collection of his poems was published with the financial assistance of his friends and he acquired some fame as a writer of "humble" beginnings. He acquired literary patrons, the most of important being the "bluestocking" Elizabeth Montagu, who also became his employer. After a dispute with Montagu, he left her service and his final years were spent in London, where he set up a bookselling business. He died in 1820 and was buried at the cemetery of St George's Chapel, near Marble Arch in London.

Life

[edit]Early life

[edit]James Woodhouse was born in Rowley Regis in the Black Country region of England in 1735.[1][2] He was the son of Joseph and Mary Woodhouse, owners of a farm, who had him baptized at St. Giles, the parish church, on 18 April 1735.[3] At this time, the area around Rowley Regis village, which was sited on a ridge crossing the Black Country, was largely rural, although the hand-made nail trade was well established in the district.[4] According to one source, Woodhouse was "taken from school" at the age of seven having learnt only to read and write.[5] He took up the trade of shoe-maker, which supported him and his family in his early years. According to the introduction to his first published collection, Woodhouse developed an "invincible inclination to reading and an insatiable thirst after knowledge" at the age of eighteen, from when he "expended all his little perquisites in the purchase of magazines".[6] He started writing poetry, to the alarm of his father who considered it a distraction from his work,[7] and made the acquaintance of the poet William Shenstone, who lived nearby at the Leasowes in Halesowen.[1]

Becomes a published poet

[edit]

Shenstone had carried out extensive landscape gardening at his estate, creating a ferme ornée, to which he allowed free access.[8] Then, after extensive damage to the estate by the public in 1759, he restricted general access. On hearing of the damage, Woodhouse wrote an elegy to Shenstone, praising him and deploring the need to close the gardens to the public.[9] From this time, Shenstone encouraged Woodhouse's literary efforts, granting the shoe-maker access to his library.[10] In January 1760, Woodhouse married Hannah Fletcher (who figures as "Daphne" in Woodhouse's writings) at Rowley Regis parish church.[11][12] They were to have 6 children who were recorded in the local parish records as well as many still-born children.[13][14] In 1763, a poem by Woodhouse about the spring season was included in a series of volumes entitled The Poetical Calendar although later the poet complained that this had been done without his knowledge and that the text was imperfect.[6][15] After Shenstone's death in 1763, Woodhouse managed to publish a collection of his poems, entitled "Poems on Sundry Occasions" (later republished as "Poems on Several Occasions") aided by a subscription made by his friends.[1][16] The collection was published in 1764, and in the same year, a single poem by Woodhouse appeared in the second volume of a collection of the works of William Shenstone.[17] By this time he had "two or three children".[9] He was supplementing his shoe-making income by teaching children to read and write but claimed to be earning only 8s per week.[1][3][9] He also acquired new literary patrons, who would assist him in his career, namely George Lyttelton of Hagley Hall and Elizabeth Montagu.[11] In his first published collection, Woodhouse also acknowledged the financial assistance of Lord Dudley and Ward, who put the poet in possession of a free school worth £10 per annum.[18]

The publication of his work inspired a humorous letter to the St. James's Chronicle, which pointed out that shoemaking and poetry writing were not incompatible tasks: "he may surely, by no unnatural association of ideas, think at one and the same time of the Feet of his Verses and the Feet of his Customers; or Hammer out a line, while he is Hammering out the sole of a shoe."[19]

As the "shoe-maker poet", Woodhouse achieved some measure of fame and came to the notice of Samuel Johnson, meeting the writer in 1765 at the invitation of Hester Thrale.[20][21] According to the later recollections of Mrs Thrale, Johnson advised the poet to: "give nights and days, sir, to the study of Addison, if you mean either to be a good writer, or, what is more worth, an honest man."[22] In his Life of Johnson, James Boswell published some recollections of a friend of Johnson's, the Rev. Dr. William Maxwell of Falkland, Ireland, claiming that Johnson had made disparaging remarks about Woodhouse, stating:[23]

He spoke with much contempt of the notice taken of Woodhouse, the poetical shoemaker. He said, it was all vanity and childishness ; and that such objects were, to those who patronised them, mere mirrors of their own superiority. 'They had better,' said he, 'furnish the man with good implements for his trade, than raise subscriptions for his poems. He may make an excellent shoemaker, but can never make a good poet. A schoolboy's exercise may be a pretty thing for a schoolboy; but it is no treat for a man.'

Also in 1765, Woodhouse had an unfortunate meeting with the new owner of the Leasowes, Captain Turnpenny. Whilst walking through Shenstone's former property with his brother and a friend, Woodhouse was beaten by Turnpenny's servants, the new owner not recognising the poet.[11]

In 1766, Woodhouse published Poems on Several Occasions, an expanded version of his collection from 1764. The volume was dedicated to Lord George Lyttelton, to whom two of the new poems in the collection were addressed,[16] whilst Elizabeth Montagu helped arrange the subscription necessary to achieve publication.[3] In the introduction to he volume, Woodhouse informed his readers that: "by the great and unexpected generosity of my Patrons, I am now enabled to apply my time chiefly to my little school". In June 1767, a poem addressed to Woodhouse was published, written by John Jones of Kidderminster, which alludes to the assistance given by Lyttleton to Woodhouse after Shenstone's death:[24]

Oh! Shenstone! Shenstone! worthy ev'ry tear,

Which Woodhouse, frantic sheds upon thy bier;

Thy loss in him I ever would deplore,

But Lyttleton commands I must no more;

That patriot peer, with pity saw thy grief,

and angel like administer'd relief

In the employ of the Montagus

[edit]

In 1767, Woodhouse found employment as a land bailiff on the Sandleford estate of Elizabeth and Edward Montagu.[25] He lived on the estate with his family and initially relations with his employers were good.[14] Letters from Elizabeth Montagu reveal that Woodhouse was an effective bailiff, working long hours during the harvest and supervising planting, ditching, and ploughing.[14] He also produced poems for special occasions such as Elizabeth's birthday. However, tensions arose between the Woodhouse family and Elizabeth Montagu and the relationship gradually soured, a rupture happening in 1778 when Woodhouse left his post, returning with his family to his native Rowley Regis.[14] During his time back in his native region, Woodhouse suffered the loss of one of his daughters, Martha, who died of smallpox.[26] He was reconciled with Elizabeth Montagu in 1781 and re-entered her employ as steward at Sandleford and at her new London home at Portman Square.[8] A final breach with Elizabeth Montagu occurred in 1788 prompted by religious and political differences and Woodhouse left her service for good.[1]

Life as a bookseller and final publications

[edit]His final years were spent in London, where he set up a bookselling business with the assistance of James Dodsley.[8] In 1788, Woodhouse published a volume of poems with the same title as his 1766 book, but with different content, namely: Poems on several occasions.[27] These were the first poems that he published since entering the service of Elizabeth and Edward Montagu in 1767. The volume included an "Address to the Public" in which he laments his difficult financial position "with the addition of an unhealthy wife, by whom I have had twenty-seven children".[28] The book, which included a poem in defence of King George III, was sold from premises at 10 Lower Brook Street, London.[29]

Woodhouse composed a number of poems during the following years although publication was delayed until the early years of the 19th century. In 1803, Woodhouse published a collection of poems entitled Norbury Park and other poems, which he dedicated to William Locke, the owner of Norbury Park.[30] At this time he had a premises at 211 Oxford Street, London.[30] The following year he published a collection of verse epistles entitled Love letters to my wife.[31][32]

He wrote a long autobiographical satirical narrative poem called The Life and Lucubrations of Crispinus Scriblerus.[33][34] The poem was published in part in 1815[35] but the complete poem was only published posthumously in 1896 by one of his descendants, the Rev. R.I. Woodhouse.[25][36] The title of the work probably alludes to the Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus, a work created by the group of 18th century writers known as the Scriblerus Club, and Crispin the patron saint of shoemakers.[37] The poem includes a very critical portrayal of Woodhouse's former patron, Elizabeth Montagu, which is thought be the reason for it not being published in full during his lifetime.[11][14]

A description of Woodhouse in his final years at his bookshop was given in an edition of Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine from 1829:[38]

tall, erect, venerable, almost patriarchal, in his appearance — in his black-velvet cap, from beneath which his grey locks descended upon his forehead, and on each side of his still fine face, — his long, black, loose gown, — and his benignant air — issuing from his little parlour with a stately step, as the tingling bell which hung over the shop door gave notice of a customer, when it was opened.

Woodhouse died in 1820, his death brought about by a collision with a carriage whilst crossing the road,[3] and was buried near Marble Arch in London at the cemetery of St George's Chapel.[1]

In his will, Woodhouse left his property to his only surviving child, Elizabeth.[39]

Poetical works

[edit]

A number of Woodhouse's early poems were written in praise of William Shenstone and his estate, The Leasowes.[11] Thus, his first collection published in 1764, included two elegies to "William Shenstone, Esq; Of the Lessowes" and a poem addressed to Shenstone, "On his indisposition in the spring, 1762"[40]

The first of these elegies begins:[40]

PARDON, O Shenstone ! an intruding strain,

Nor blame the boldness of a village swain,

Who feels ambition haunt the lowliest cell,

And dares on thy distinguished name to dwell;

Let no censorious frown deform thy face,

But gladd'ning smiles maintain their wonted grace.

Hence, vain surmise! my muse can ne'er offend

One; who so good? To all mankind a friend.

Also included in the collection was: The Lessowes. A Poem. Woodhouse's first collection also included two other poems: Benevolence, an Ode which was inscribed to some "gentlemen and ladies in London" who had made a small subscription for him, and Spring.[40]

Woodhouse's second collection from 1766, included the poems from the earlier volume but added: Wrote at the Lessowes after Mr Shenstone's Death, Palemon and Collinet, a Pastoral Elegy, and two poems inscribed to Lord Lyttelton.[16] Also included was an Ode to Apollo and a poem inscribed to a countess on the death of a daughter.

His collection from 1788, Poems on several occasions, never before published, comprised the following poems: "Ridicule", "An Elegy on a favourite Child who died of the small-pox" (written in 1779 following the death of his daughter, Martha),[26] "Elegy written in 1784, from the country", "Ode to the Lily" and "A Morning Rhapsody".[28] A contemporary review of the volume stated that Ridicule seemed "principally intended to expose the fallaciousness and scurrility of Peter Pindar".[28]

Woodhouse's next publication, Norbury Park: A Poem : with Several Others included eleven poems and was published in May 1803.[41] Almost half of the volume was taken up with a poem entitled: Norbury Park: A Poem, inscribed to the owner of the park, W. Lock. There were also five verse epistles, namely: "Epistle to a young lady of title", "Epistle, to the Rev. Mr. Sellon", "Epistle to a friend", "Epistle to the same" (following on from An Ode to a friend on his marriage), and one written to the deceased William Shenstone: Epistle, to Shenstone, in the Shades. Also included were To my wife and children, under a severe affliction in my eyes, and To my wife, on her wishing to see me half an hour. Two other poems made up the collection: "The Boy and the Butterfly" and "Autumn and the Redbreast, An Ode".[30]

The latter poem, inscribed to Woodhouse's wife Hannah, begins:[30]

Let happy Poets strike the string,

And chaunt the matchless charms of Spring;

The Spring, to me, displays no charms—

It calls me from my Hannah's arms!

'Tis thou mak'st Nature still appear

Array'd with charms throughout the Year.

Mak'st all her beauties blissful shine,

Her looks, her laughs, her lays, divine.

In the year after Norbury Park was published, Woodhouse brought out Love letters to my wife. The work consisted of nine verse epistles, which had been written in 1789. Despite the title of the work, the verses are concerned with moral and religious questions rather than marital love.[31] According to a contemporary review, in the work, Woodhouse "satirizes the fashionable vices and follies of the great".[42] In 1809, The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure published a tenth letter in the sequence, Love letters to my wife.[43] The opening lines of the poem are:[43]

Dear Hannah, In my last I strove to give

A partial sketch how peccant courtiers live.

To shew while we, dull duteous peasants, plod

In serving man, or glorifying God,

How they their days idolatrously pass

In glorifying self before their glass,

Or, adding phrenzy to that foolish crime,

In dissipation spend their precious time.

Woodhouse's final work: The Life and Lucubrations of Crispinus Scriblerus was only published in part during his lifetime. It was first published in 1815.[35][44] Woodhouse's name was not mentioned in the publication, the authorship of which was ascribed to a "Friend" of Crispinus.[35] It was not until 1896 when the work appeared in its full form, published by a descendant, Rev. Reginald Illingsworth Woodhouse, Rector of Merstham, who brought out a two volume edition of Woodhouse's works entitled: The Life and Poetical Works of James Woodhouse (1735-1820).[45] The poem is an autobiographical work and, with its 28,000 lines, is considerably longer than any of Woodhouse's previous poems, taking up all of volume one of his complete published works and a significant part of volume two.[46]

The opening lines recall the Rowley Hills of Woodhouse's early days:[47]

High, on those Hills, whose scarce-recorded Name,

Has weakly whisper'd from the trump of Fame;

Just to announce, distinct, the simple sound,

O'er other swarming heights, and hamlets, round—

Unless like Name of Bristol's ancient Bard,

Among the tuneful tribes may meet regard,

Which hapless Chatterton's prolific lays

Wreath'd round his brows with never-fading bays;

Or poor Crispinus', oaten pipe, alone,

Might serve to raise the sound one semitone.

There 'mid the Cots that look o'er southern lands,

Near the blest spot where Heav'n's fair temple stands,

Once dwelt an humble, but an honest, Pair,

Of manners, rustic, but of morals rare!

Selected works

[edit]- To William Shenstone Esq.; in his sickness, 1764

- Poems on sundry occasions, 1764

- Poems on several occasions, 1766

- Poems on several occasions, 1788

- Norbury Park and other poems, 1803

- Love letters to my wife, 1804

- The Life and Lucubrations of Crispinus Scriblerus, 1815 (complete poem published 1896)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Hackwood, Frederick William (1911). Staffordshire Worthies. Stafford: Chronicle Press. pp. 83–87.

- ^ Jones, John; Southey, Robert (1831). Attempts in Verse. London: John Murray. pp. 114–121.

- ^ a b c d Christmas, William J. (3 October 2013). "Woodhouse, James". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29924. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Chitham, Edward (2008). Rowley Regis: A History. Phillimore & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1860774188.

- ^ Annual register, or a view of the history and politics and literature for the year. London: J. Dodsley. 1764. pp. 64–66. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ a b Woodhouse, James (1764). Poems on sundry occasions. London: W. Richardson and S. Clark. pp. i–vii. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t8qc09g1s.

- ^ Montagu, Elizabeth (1906). Mrs. Montague, "Queen of the blues", her letters and friendships from 1762-1800. Vol. 1. Scotland: Houghton Mifflin. p. 163. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Van Hagen, Steve (2015). Gary Day; Jack Lynch (eds.). The Encyclopedia of British Literature, 3 Volume Set: 1660 - 1789. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1366–1367. ISBN 9781444330205.

- ^ a b c Woodhouse, James (1764). Poems on Sundry Occasions. London: W. Richardson and S. Clark. pp. 1–8. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t8qc09g1s.

- ^ Shenstone, William (1769). The Works, in Verse and Prose, of William Shenstone: With Decorations. London: J. Dodsley. p. 394.

- ^ a b c d e Bridgen, Adam J. (Spring 2017). "Patronage, Punch-Ups, and Polite Correspondence: The Radical Background of James Woodhouse's Early Poetry". Huntington Library Quarterly. 80 (1): 99–134. doi:10.1353/hlq.2017.0004. hdl:10023/24832. S2CID 151429593.

- ^ Adams, Percy W. L. (1915). Rowley Regis Parish Register. Vol. 3. Staffordshire Parish Registers Society. pp. 859.

- ^ Van-Hagen, Stephen (2007). Joseph Woodhouse: in The Literary Encyclopedia. Vol. 1.2.1.05. The Literary Dictionary Company Limited. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Hornbeak, Katherine G. (1949). Age Of Johnson, Essays presented to Chauncey Brewster Tinker. New Haven, USA: Yale University Press. pp. 349–361.

- ^ The Poetical Calendar. Vol. 3. London: Dryden Leach. 1763. pp. 86–95. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Woodhouse, James (1766). Poems on Several Occasions. London: Dodsley.

- ^ Shenstone, William (1764). The works in verse and prose, of William Shenstone, esq. Vol. 2. Darwin Online. London: R. and J. Dodsley. pp. 387–390.

- ^ Woodhouse, James (1764). Poems on Sundry Occasions. London: W. Richardson and S. Clark. p. 109. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t8qc09g1s.

- ^ Colman, George (1787). Prose on several occasions;accompanied with some pieces in verse. London: T. Cadel. pp. 47–49. hdl:2027/nyp.33433067289656.

- ^ Montague, Elizabeth (1906). Mrs. Montague, "Queen of the blues", her letters and friendships from 1762-1800. Vol. 2. Scotland: Houghton Mifflin. p. 270. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Boswell, James (1887). Hill, George Birkbeck (ed.). "Life Of Johnson". www.gutenberg.org. Appendix F. H. Baldwin and Son. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Russell, John Fuller (1847). The Life of Dr. Samuel Johnson. London: James Burns. pp. 75.

- ^ Boswell, James (1889). The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL. D.: Together with The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides. Vol. 2. London: George Bell and Sons. pp. 116–125.

- ^ The London Magazine, or, Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer. Vol. 36. London: R. Baldwin. 1767. pp. 303–304. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ a b Christmas, William J. (2001). The Lab'ring Muses. Cranbury, NJ: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 9780874137477.

- ^ a b Shuttleton, David (17 May 2007). Smallpox and the Literary Imagination, 1660-1820. Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 9780521872096.

- ^ The Critical Review, Or, Annals of Literature. Vol. 66. London: A. Hamilton. 1788. p. 575.

- ^ a b c THE GENERAL MAGAZINE AND IMPARTIAL REVIEW. London: Bellamy and Robarts. 1788. pp. 356–357.

- ^ Griffiths, Ralph; Griffiths, George Edward (1788). The Monthly Review. Vol. 79. London: R. Griffiths. p. 167.

- ^ a b c d Woodhouse, James (1803). Norbury Park: A Poem : with Several Others, Written on Various Occasions. London: Watts and Bridgewater.

- ^ a b Overton, W.J. (2006). Gerrard (ed.). The verse epistle, in A companion to Eighteenth Century Poetry (PDF). Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-1316-8. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ The Monthly Review. London: Straban and Preston. 1804. p. 426.

- ^ Whitford, Robert C. (1919). Satire's View of Sentimentalism in the Days of George the Third. Vol. 18. The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. pp. 158–159.

- ^ "The Monthly Review". HathiTrust. London: J. Porter. 1816. pp. 216–217. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ a b c "The New Monthly Magazine". HathiTrust. London: H. Colburn. 1815. p. 152. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Keegan, Bridget (2008). British Labouring-Class Nature Poetry, 1730–1837. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230536968.

- ^ Baird, Ileana (2014). Social Networks in the Long Eighteenth Century. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 331. ISBN 9781443871358.

- ^ "Blackwood's Edinburgh magazine". HathiTrust. William Blackwood. 1829. pp. 753–754. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "Will of James Woodhouse". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. PROB 11/1634/135. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Woodhouse, James (1764). Poems on Sundry Occasions. London: W. Richardson and S. Clark. pp. 1–109. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t8qc09g1s.

- ^ "This day is published". Morning Post. 3 May 1803. p. 2. Retrieved 13 May 2019 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Arthur Aikin, ed. (1805). The Annual review and history of literature. Vol. 3. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme. p. 596.

- ^ a b The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure. Vol. 12. London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones. 1809. p. 138.

- ^ "This day is published". Morning Post. 6 January 1815. p. 2. Retrieved 20 May 2019 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Woodhouse, James (1896). The Life and Poetical Works of James Woodhouse (1735-1820). Leadenhall Press Limited.

- ^ Baird, Ileana (2014). Social Networks in the Long Eighteenth Century. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 314. ISBN 9781443871358.

- ^ Woodhouse, James (1896). The Life and Poetical Works of James Woodhouse (1735-1820). London, New York: Leadenhall Press. p. 9.