Ireland–NATO relations

| |

NATO |

Ireland |

|---|---|

The Republic of Ireland and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have had a formal relationship since 1999, when Ireland joined as a member of the NATO Partnership for Peace (PfP) program and signed up to NATO's Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC). To date, Ireland has not sought to become a member of NATO due to its traditional policy of military neutrality. In 2024, the Republic of Ireland joined NATO's Individually Tailored Partnership Programme (ITPP) in order to increase its' capabilities at countering potential threats to undersea infrastructure.[1]

Ireland with Austria, Cyprus and Malta are the only members of the European Union that are not members of NATO.

History

[edit]Background: Irish stance on military alliances prior to NATO's founding

[edit]Following the Irish War of Independence with the United Kingdom, the Irish Free State was established in 1922. Its constitution stated, "Save in the case of actual invasion, the Irish Free State ... shall not be committed to active participation in any war without the assent of the Oireachtas [parliament]".

Many countries made neutrality declarations during World War II. However, Ireland (which refers to the period as the emergency) was one of a handful of European states to remain neutral to the end of the war. For Taoiseach Éamon de Valera, the emphasis of Irish neutrality was on the preservation of Irish sovereignty. The Irish government had good reason to be concerned that supporting either side in the conflict could reignite grievances of the Irish Civil War, as there were pro- and anti-fascist movements in Ireland. The possibility that the Irish Republican Army might link up with German agents (in line with the Irish republican tradition of courting allies in Europe against the colonial power of the UK to secure their full independence), and thereby compromising Irish non-involvement, was considered. Additionally, there were fears that the United Kingdom, eager to secure Irish ports for their air and naval forces, might use the attacks as a pretext for an invasion of Ireland. It was believed that Ireland would take the German side if the United Kingdom attempted to invade Ireland, but would take the British side if invaded by Nazi Germany. In 1940, British envoy Malcolm MacDonald proposed an end to the partition of Ireland and acceptance of "the principle of a United Ireland" if the independent Irish state abandoned its neutrality and immediately joined the war against Germany and Italy. However De Valera rejected the proposals, as he worried that since unification would need to be agreed upon by "representatives of the government of Éire and the government of Northern Ireland" which distrusted the other intensely, there was "no guarantee that in the end we would have a united Ireland" and that it "would commit us definitely to an immediate abandonment of our neutrality".[2]

Ireland's fulfillment to the letter of the rules of neutrality has been questioned. Ireland supplied important secret intelligence to the Allies, for instance, the date of D-Day was decided on the basis of incoming Atlantic weather information, some of it supplied by Ireland but kept from Germany. Ireland also secretly allowed Allied aircraft to use the Donegal Corridor, making it possible for British planes to attack German U-boats in the mid-Atlantic. While both Axis and Allied pilots who crash landed in Ireland were interned,[3] downed Royal Air Force airmen were repatriated.[4][5]

1949–1973: Early relations

[edit]Ireland had been willing in 1949 to negotiate a bilateral defence pact with the United States, but opposed joining NATO until the question of Northern Ireland was resolved with the United Kingdom (see The Troubles 1968–1998).[6]

During the negotiations to establish NATO in 1949, the Irish government was consulted on potentially becoming a member. A representative of the US State Department informed Irish ambassador Seán Nunan that the states founding NATO wanted Ireland to join, and that if the Irish government was supportive it would be formally invited by the other parties. While the Irish government expressed its support for the goals of NATO, it opposed joining as it did not wish to be in an alliance with the United Kingdom (who was a signatory to the agreement founding NATO) with which it disputed the sovereignty over Northern Ireland.[7][8][9][10] Thus Irish reunification became a condition for Ireland joining NATO, which was not acceptable to the UK.[11][12] Ireland offered to set up a separate alliance with the United States but this was refused. This offer was linked in part to the $133 million received from the Marshall Aid Plan. Subsequently, Irish neutrality became more established and the country never applied to join NATO as a full member.

1973–1999: Initial European co-operation

[edit]

Ireland continued their policy of military neutrality during the Cold War, though the country aligned economically and politically with the west and joined the European Communities (EC) in 1973. Following the end of the Cold War the EC was transformed into the European Union, and a Common Foreign and Security Policy was adopted.

1999–present: Partnership for Peace, EU defence co-operation

[edit]Official NATO–Ireland relations began in 1999 when Ireland became a signatory to NATO's Partnership for Peace programme and the alliance's Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council.[6] Since then, NATO and Ireland have actively cooperated on peacekeeping, humanitarian, rescue, and crisis management issues and have developed practical cooperation in other military areas of mutual interest, under Ireland's Individual Partnership Programme (IPP) and Individual Partnership and Cooperation Programme (IPCP), which is jointly agreed every two years.[13] Irish cooperation with NATO is centred around the country's historic policy of neutrality in armed conflicts, which allows the Irish military to deploy on peacekeeping and humanitarian missions where there is a mandate from the United Nations (UN Security Council resolution or UN General Assembly resolution), subject to cabinet and Dáil Éireann (Irish lower house of parliament) approval. This is known as Ireland's "triple-lock" policy.[14][15]

Ireland participates in the Partnership for Peace (PfP) Planning and Review Process (PARP), which aims to increase the interoperability of the Irish armed forces, the Defence Forces, with other NATO member states and bring them into line with accepted international military standards so as to successfully deploy with other professional forces on peace operations overseas.[16]

Ireland supports the ongoing NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR) and has done so since 1999, and supplied a limited number of troops to the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan (2001–2014), as these were sanctioned by UN Security Council resolutions. The ISAF counter-IED programme in Afghanistan was largely developed by senior officers from the Irish Army Ordnance Corps. Previously in 1997, before Ireland had a formal relationship with the alliance, it deployed personnel in support of the NATO-led peacekeeping operation in Bosnia and Herzegovina where much of its forces formed part of an international military police company primarily operating in Sarajevo.[17][18]

Ireland sought recognition for its neutrality in EU treaties, and argued that its neutrality did not mean that Ireland should avoid engagement in international affairs such as peacekeeping operations.[19] Since the enactment of the Lisbon Treaty, EU members are bound by TEU, Article 42.7, which obliges states to assist a fellow member that is the victim of armed aggression. It accords "an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in [other member states'] power" but would "not prejudice the specific character of the security and defense policy of certain Member States" (neutral policies), allowing members to respond with non-military aid. Ireland's constitution prohibits participating in such a common defence.

With the launch of Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) in defense at the end of 2017, the EU's activity on military matters has increased. The policy was designed to be inclusive and allows states to opt in or out of specific forms of military cooperation. That has allowed most of the neutral states to participate, but opinions still vary. Some members of the Irish Parliament considered Ireland's joining PESCO as an abandonment of neutrality. It was passed with the government arguing that its opt-in nature allowed Ireland to "join elements of PESCO that were beneficial such as counter-terrorism, cybersecurity and peacekeeping... what we are not going to be doing is buying aircraft carriers and fighter jets".

Currently no major political party supports accession to NATO as their party line.[20] There has been, and continues to be, a minority of individual politicians and groups of politicians who support Ireland joining NATO, mainly but not limited to the centre-right Fine Gael party (in 2013, the party's youth wing Young Fine Gael passed a motion calling on the Irish government to start accession talks with NATO).[21][22][23] It had been widely understood that a referendum would have to be held before any changes could be made to neutrality or to joining NATO,[24] though in June 2022, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine had begun, Taoiseach Micheál Martin stated that there was no legal requirement for a referendum on the matter since it was "a policy decision of government.”[25] However, he later clarified that politically it would be necessary.[26]

Former Secretary General of NATO Anders Fogh Rasmussen said during a visit to Dublin in 2013 that the "door is open" for Ireland to join NATO at any time, saying that the country would be "warmly welcomed" and is already viewed as a "very important partner".[27]

2001–2005: US military stopovers in Ireland

[edit]Ireland's air facilities are regularly used by the United States military for the transit of military personnel overseas, mainly to the Middle East. The Irish government began supplying military and civilian air facilities in Ireland for use by the armed forces of the United States during the 1991 First Gulf War. Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, the Irish government offered the use of Irish airspace and airports to the US military in support of the war in Afghanistan and the 2003 invasion of Iraq, on the condition that aircraft be unarmed, with no cargo of arms, ammunition or explosives, and do not engage in intelligence gathering, and that the flights in question do not form part of military exercises or operations at the time.[28] Casement Aerodrome, Baldonnel (military) and Shannon Airport (civil), used as stopover hubs, have seen more than 2.4 million American troops pass through from 2002 to 2014.[29] An average of more than 500 US troops passed through Shannon every day during that period.[30]

US use of Baldonnel and Shannon has been the subject of controversy in Ireland due to revelations in December 2005 by the BBC investigative television programme Newsnight that Shannon Airport was used on at least 33 occasions for secret Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) flights, operated by front companies, as part of a US government policy known as "extraordinary rendition". The New York Times also reported the number to be 33, though referring to "Ireland" as a whole rather than Shannon specifically, while Amnesty International alleged the number of flights to be over 50. Baldonnel has seen similar claims, but these are impossible to verify as it is a military airbase. Both the US and Irish authorities have denied the allegations.[31] According to leaked American diplomatic cables (WikiLeaks) from the US Embassy in Dublin, the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs at the time told the chief of mission that the Irish authorities suspected the CIA had on a number of occasions used aircraft disguised as commercial flights to transfer prisoners detained in Afghanistan to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba for interrogation and detention – using Shannon to refuel in the process – and warning of the legal implications for both Ireland and the United States as a result.[32]

Defending Irish airspace

[edit]

The Irish Air Corps, the air force element of the Irish Defence Forces, is widely perceived as incapable of defending Ireland's airspace due to a significant lack of funding, equipment, training and personnel. Its role is mainly limited to fisheries protection in support of the Irish Naval Service, and non-military air services such as policing, air ambulance, VIP transport, search and rescue and logistical support. As Ireland is not a member of NATO it does not benefit from integrated European military radar detection systems nor NATO-level equipment. The Air Corps does not have the ability to intercept fast jet aircraft, and previous air incursions have seen the British Royal Air Force (RAF), a NATO ally, respond to and escort unwelcome aircraft out of Irish-controlled airspace.[33]

The typical cruising air speed for commercial passenger jets is 878 to 926 km/h,[34] while the top speed of a Pilatus PC-9 from the Air Corps is just 593 km/h.[35]

In February 2015, two Russian Tupolev Tu-95 "Bear" nuclear-capable strategic bombers flew close to Irish airspace without entering it, with their transponders switched off and failed to file flight plans, causing serious concern at the Irish Aviation Authority (IAA), which was forced to divert a number of civil passenger aircraft out of the path of the Russian bombers as a precautionary measure.[36] The Russian military aircraft were interrogated by RAF Eurofighter Typhoon jets scrambled from the United Kingdom, demonstrating the lack of an Irish military response and the reliance on the UK for the protection of Irish airspace. The Russian bombers did not enter sovereign Irish airspace, but the Department of Defence lodged a complaint with Russian diplomats in Dublin, and the Minister for Defence publicly vented his anger at the incursions, and the disruption and danger it caused to commercial air traffic. It later emerged that the Norwegian military (a NATO member) had intercepted Russian military communications indicating that one of the aircraft was carrying a nuclear payload (a nuclear missile that was not "live" at the time, but had the ability to be made "live" mid-air). British reports visually confirmed that one of the bombers was carrying a nuclear warhead.[37] The fact that Russian military bombers carrying nuclear weapons flew within 12 nautical miles of the Irish coast caused significant alarm.[38]

This section needs to be updated. (February 2022) |

In July 2015, the Irish government revealed plans to purchase a ground-based long-range air surveillance radar system for the Irish Aviation Authority and Defence Forces to keep track of covert aircraft flying in Irish-controlled airspace, including military aircraft that do not file a flight plan and have their transponders switched off. Minister for Defence Simon Coveney said the increased capability would give better coverage of the Atlantic airspace over which the IAA has responsibility. The long-range surveillance radar is reported to cost €10 million, and is seen as a priority purchase to provide the civilian and military authorities with an improved competency in monitoring aerial incursions.[39] The decision was widely attributed directly to the Russian incursions.

Agreements with the UK on air defence

[edit]The possibility of a hijacked airliner in Irish airspace would most likely result in a Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) response by NATO aircraft, and it is believed that there are secret agreements in place with the British government regarding the defence of Irish airspace.[40][41]

In 2016 it was reported in the Irish press that several years previously confidential agreements were made between the Irish and British governments concerning the protection of Irish airspace from terrorist threats. The reports revealed that the Irish Department of Defence, Department of Foreign Affairs and Irish Aviation Authority entered into a bilateral agreement with the British RAF, Civil Aviation Authority, Ministry for Defence and Foreign and Commonwealth Office permitting the British military to conduct armed operations inside Irish sovereign or Irish-controlled airspace in the event of a real time or envisaged threat of an aerial terrorist-related attack on Ireland or on a neighbouring country.[42]

Opinion polling on Irish NATO membership

[edit]| Dates conducted |

Pollster | Client | Sample size |

Support | Opposed | Neutral or DK |

Lead | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 March 2024 | Sweden accedes to NATO | |||||||

| June 2023 | Red C | Business Post | ? | 34% | 38% | 28% | 4% | [43] |

| 4 April 2023 | Finland accedes to NATO | |||||||

| August 2022 | Behaviour Wise[44] | 1,845 | 52% | 48% | - | 4% | [45] | |

| April 2022 | Behaviors and Attitudes | The Sunday Times | 957 | 30% | 70% | - | 40% | [46] |

| 26 March 2022 | Red C | Business Post | ? | 48% | 39% | 13% | 9% | [47] |

| 4 March 2022 | Ireland Thinks | Sunday Independent | 1,011 | 37% | 52% | 11% | 15% | [48] |

| 24 February 2022 | Russia invades Ukraine | |||||||

| 16 March 2014 | Russia annexes Crimea | |||||||

| 7 August 2008 | Russia invades Georgia | |||||||

| 5 October 1996 | MRBI | Irish Times | ? | 13% | ? | ? | ? | [49] |

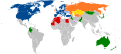

Ireland's foreign relations with NATO member states

[edit]See also

[edit]- Foreign relations of Ireland

- Foreign relations of NATO

- Irish neutrality

- Neutral member states in the European Union

- Ireland–United States relations

- Ireland–United Kingdom relations

- Enlargement of NATO

- European Union–United Kingdom relations

- European Union–NATO relations

- Ireland–United Kingdom border

- NATO open door policy

- Partnership for Peace

NATO relations of other EU member states outside NATO:

References

[edit]- ^ "Ireland in new agreement with Nato to counter potential threats to undersea infrastructure". www.thejournal.ie. 2024-02-09. Retrieved 2024-12-21.

- ^ Garvin, Tom (2011). News from a new republic: Ireland in the 1950s. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-4659-8. OCLC 636911981.

- ^ "The WWII camp where Allies and Germans mixed". BBC News. 28 June 2011.

- ^ Burke, Dan. "Benevolent Neutrality". The War Room. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ McCabe, Joe (May 31, 2014). "How Blacksod lighthouse changed the course of the Second World War". independent. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ^ a b Sloan, Stanley R. (23 April 2013). "NATO's 'neutral' European partners: valuable contributors or free riders?". NATO. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Fanning, Ronan (1979). "The United States and Irish Participation in Nato: The Debate of 1950". Irish Studies in International Affairs. 1 (1): 38–48. ISSN 0332-1460. JSTOR 30001704.

- ^ Aide-mémoire to US State Department official on issue of NATO membership, 8 February 1949, National Archives of Ireland, File NAI DEA 305/74 a, Ireland and NATO

- ^ Keane, Elizabeth (2004). "'Coming out of the Cave': The First Inter-Party Government, the Council of Europe and NATO". Irish Studies in International Affairs. 15: 167–190. doi:10.3318/ISIA.2004.15.1.167. JSTOR 30002085.

- ^ Dáil Éireann, Volume 114, 23 February 1949, Oral Answers – Atlantic Pact, 324 (Ceisteanna—Questions. Oral Answers. - Atlantic Pact. Wednesday, 23 February 1949) http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/debates%20authoring/debateswebpack.nsf/takes/dail1949022300018?opendocument Accessed 20150927

- ^ Cottey, Andrew (5 December 2017). The European Neutrals and NATO: Non-alignment, Partnership, Membership?. Springer Publishing. p. 156. ISBN 9781137595249.

- ^ "Neutral European countries". nato.gov.si.

- ^ "NATO's relations with Ireland". NATO. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ "Ireland: dealing with NATO and neutrality". NATO Review Magazine. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ Lee, Dorcha (18 September 2014). "Time to adjust the peacekeeping triple lock". The Irish Times. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Defence Questions: Irish cooperation with NATO in Ukraine". Eoghan Murphy TD. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Current Missions > ISAF". Defence Forces Ireland. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Current Missions > KFOR". Defence Forces Ireland. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Neutrality - Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade". Dfa.ie.

- ^ O'Carroll, Sinead (13 February 2013). "Poll: Should Ireland give up its neutrality?". thejournal.ie. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "YFG Calls for Ireland to Engage in Accession Talks with NATO". Young Fine Gael (YFG). 22 July 2013. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ McCullagh, David (19 May 2015). "David McCullagh blogs on Ireland's defence policy". RTÉ Prime Time. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Roche, Barry (30 August 2014). "Ireland should change position on military neutrality, says academic". The Irish Times. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Challenges and opportunities abroad: White paper on foreign policy" (PDF). Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Ireland. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ O'Leary, Naomi (2022-06-08). "Ireland would not need referendum to join Nato, says Taoiseach". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- ^ Hedgecoe, Guy (2022-06-29). "Referendum would have to be held before Ireland joined Nato, Taoiseach says". Irish Times. Retrieved 2022-08-06.

- ^ Lynch, Suzanne (11 February 2013). "Door is open for Ireland to join Nato, says military alliance's chief". The Irish Times. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "50 aircraft refused access to Irish airspace over munition concerns in 2016". Irish Examiner. 9 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ McConnell, Daniel (10 August 2014). "15pc rise in number of US military flights landing at Shannon". Irish Independent. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Clonan, Tom (15 August 2016). "Tom Clonan: Why it's time to have an open and honest debate about our neutrality". thejournal.ie. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ "Gilmore accepts US assurance of no rendition flights through Shannon". Thejournal.ie. 20 September 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "Rendition flights 'used Shannon'". The Irish Times. 17 December 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ O’Riordan, Sean (20 February 2015). "Russian nuclear bombers enter Irish airspace for second time". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ "Phases Of A Flight". REStARTS. Archived from the original on 24 August 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2003–2004. Jackson. 2003. pp. 455–456.

- ^ O’Riordan, Sean (3 March 2015). "Passenger planes dodged Russian bombers". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Giannangeli, Marco (1 February 2015). "Intercepted Russian bomber was carrying a nuclear missile over the Channel". The Express. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ O’Riordan, Sean (12 February 2015). "Russian bomber in Irish air space 'had nuclear weapon'". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ O'Brien, Stephen (5 July 2015). "€10m radar goes to the front line of military shopping list". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 6 July 2015.[dead link]

- ^ Lavery, Don (2 March 2003). "Government's secret plan to ask Britain for help if attacked". Irish Independent. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ O’Riordan, Sean (11 February 2015). "How much to protect skies above Ireland?". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ O’Riordan, Sean (8 August 2016). "RAF tornado jets could shoot down hijacked planes in Irish airspace". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ https://www.redcresearch.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Business-Post-RED-C-Opinion-Poll-Report-June-23.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Public divided on Nato membership, survey finds". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2023-07-24.

- ^ Carswell, Simon (August 28, 2022). "Slim majority of Irish public support joining Nato, new poll shows". The Irish Times.

- ^ Mahon, Brian (26 April 2022). "70% of voters are against Ireland joining Nato". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Pogatchnik, Shawn (2022-03-27). "Poll: More Irish want to join NATO in wake of Ukraine invasion". Politico. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- ^ Cunningham, Kevin (2022-03-09). "The Russian Invasion of Ukraine". The Evidence. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ^ Sinnott, Richard (October 5, 1996). "Poll shows a symbolic support for neutrality". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018.