Artificial intelligence

| Part of a series on |

| Artificial intelligence |

|---|

Artificial intelligence (AI), in its broadest sense, is intelligence exhibited by machines, particularly computer systems. It is a field of research in computer science that develops and studies methods and software that enable machines to perceive their environment and use learning and intelligence to take actions that maximize their chances of achieving defined goals.[1] Such machines may be called AIs.

Some high-profile applications of AI include advanced web search engines (e.g., Google Search); recommendation systems (used by YouTube, Amazon, and Netflix); interacting via human speech (e.g., Google Assistant, Siri, and Alexa); autonomous vehicles (e.g., Waymo); generative and creative tools (e.g., ChatGPT, and AI art); and superhuman play and analysis in strategy games (e.g., chess and Go). However, many AI applications are not perceived as AI: "A lot of cutting edge AI has filtered into general applications, often without being called AI because once something becomes useful enough and common enough it's not labeled AI anymore."[2][3]

The various subfields of AI research are centered around particular goals and the use of particular tools. The traditional goals of AI research include reasoning, knowledge representation, planning, learning, natural language processing, perception, and support for robotics.[a] General intelligence—the ability to complete any task performable by a human on an at least equal level—is among the field's long-term goals.[4] To reach these goals, AI researchers have adapted and integrated a wide range of techniques, including search and mathematical optimization, formal logic, artificial neural networks, and methods based on statistics, operations research, and economics.[b] AI also draws upon psychology, linguistics, philosophy, neuroscience, and other fields.[5]

Artificial intelligence was founded as an academic discipline in 1956,[6] and the field went through multiple cycles of optimism,[7][8] followed by periods of disappointment and loss of funding, known as AI winter.[9][10] Funding and interest vastly increased after 2012 when deep learning outperformed previous AI techniques.[11] This growth accelerated further after 2017 with the transformer architecture,[12] and by the early 2020s hundreds of billions of dollars were being invested in AI (known as the "AI boom"). The widespread use of AI in the 21st century exposed several unintended consequences and harms in the present and raised concerns about its risks and long-term effects in the future, prompting discussions about regulatory policies to ensure the safety and benefits of the technology.

Goals

The general problem of simulating (or creating) intelligence has been broken into subproblems. These consist of particular traits or capabilities that researchers expect an intelligent system to display. The traits described below have received the most attention and cover the scope of AI research.[a]

Reasoning and problem-solving

Early researchers developed algorithms that imitated step-by-step reasoning that humans use when they solve puzzles or make logical deductions.[13] By the late 1980s and 1990s, methods were developed for dealing with uncertain or incomplete information, employing concepts from probability and economics.[14]

Many of these algorithms are insufficient for solving large reasoning problems because they experience a "combinatorial explosion": They become exponentially slower as the problems grow.[15] Even humans rarely use the step-by-step deduction that early AI research could model. They solve most of their problems using fast, intuitive judgments.[16] Accurate and efficient reasoning is an unsolved problem.

Knowledge representation

Knowledge representation and knowledge engineering[17] allow AI programs to answer questions intelligently and make deductions about real-world facts. Formal knowledge representations are used in content-based indexing and retrieval,[18] scene interpretation,[19] clinical decision support,[20] knowledge discovery (mining "interesting" and actionable inferences from large databases),[21] and other areas.[22]

A knowledge base is a body of knowledge represented in a form that can be used by a program. An ontology is the set of objects, relations, concepts, and properties used by a particular domain of knowledge.[23] Knowledge bases need to represent things such as objects, properties, categories, and relations between objects;[24] situations, events, states, and time;[25] causes and effects;[26] knowledge about knowledge (what we know about what other people know);[27] default reasoning (things that humans assume are true until they are told differently and will remain true even when other facts are changing);[28] and many other aspects and domains of knowledge.

Among the most difficult problems in knowledge representation are the breadth of commonsense knowledge (the set of atomic facts that the average person knows is enormous);[29] and the sub-symbolic form of most commonsense knowledge (much of what people know is not represented as "facts" or "statements" that they could express verbally).[16] There is also the difficulty of knowledge acquisition, the problem of obtaining knowledge for AI applications.[c]

Planning and decision-making

An "agent" is anything that perceives and takes actions in the world. A rational agent has goals or preferences and takes actions to make them happen.[d][32] In automated planning, the agent has a specific goal.[33] In automated decision-making, the agent has preferences—there are some situations it would prefer to be in, and some situations it is trying to avoid. The decision-making agent assigns a number to each situation (called the "utility") that measures how much the agent prefers it. For each possible action, it can calculate the "expected utility": the utility of all possible outcomes of the action, weighted by the probability that the outcome will occur. It can then choose the action with the maximum expected utility.[34]

In classical planning, the agent knows exactly what the effect of any action will be.[35] In most real-world problems, however, the agent may not be certain about the situation they are in (it is "unknown" or "unobservable") and it may not know for certain what will happen after each possible action (it is not "deterministic"). It must choose an action by making a probabilistic guess and then reassess the situation to see if the action worked.[36]

In some problems, the agent's preferences may be uncertain, especially if there are other agents or humans involved. These can be learned (e.g., with inverse reinforcement learning), or the agent can seek information to improve its preferences.[37] Information value theory can be used to weigh the value of exploratory or experimental actions.[38] The space of possible future actions and situations is typically intractably large, so the agents must take actions and evaluate situations while being uncertain of what the outcome will be.

A Markov decision process has a transition model that describes the probability that a particular action will change the state in a particular way and a reward function that supplies the utility of each state and the cost of each action. A policy associates a decision with each possible state. The policy could be calculated (e.g., by iteration), be heuristic, or it can be learned.[39]

Game theory describes the rational behavior of multiple interacting agents and is used in AI programs that make decisions that involve other agents.[40]

Learning

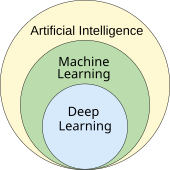

Machine learning is the study of programs that can improve their performance on a given task automatically.[41] It has been a part of AI from the beginning.[e]

There are several kinds of machine learning. Unsupervised learning analyzes a stream of data and finds patterns and makes predictions without any other guidance.[44] Supervised learning requires labeling the training data with the expected answers, and comes in two main varieties: classification (where the program must learn to predict what category the input belongs in) and regression (where the program must deduce a numeric function based on numeric input).[45]

In reinforcement learning, the agent is rewarded for good responses and punished for bad ones. The agent learns to choose responses that are classified as "good".[46] Transfer learning is when the knowledge gained from one problem is applied to a new problem.[47] Deep learning is a type of machine learning that runs inputs through biologically inspired artificial neural networks for all of these types of learning.[48]

Computational learning theory can assess learners by computational complexity, by sample complexity (how much data is required), or by other notions of optimization.[49]

Natural language processing

Natural language processing (NLP)[50] allows programs to read, write and communicate in human languages such as English. Specific problems include speech recognition, speech synthesis, machine translation, information extraction, information retrieval and question answering.[51]

Early work, based on Noam Chomsky's generative grammar and semantic networks, had difficulty with word-sense disambiguation[f] unless restricted to small domains called "micro-worlds" (due to the common sense knowledge problem[29]). Margaret Masterman believed that it was meaning and not grammar that was the key to understanding languages, and that thesauri and not dictionaries should be the basis of computational language structure.

Modern deep learning techniques for NLP include word embedding (representing words, typically as vectors encoding their meaning),[52] transformers (a deep learning architecture using an attention mechanism),[53] and others.[54] In 2019, generative pre-trained transformer (or "GPT") language models began to generate coherent text,[55][56] and by 2023, these models were able to get human-level scores on the bar exam, SAT test, GRE test, and many other real-world applications.[57]

Perception

Machine perception is the ability to use input from sensors (such as cameras, microphones, wireless signals, active lidar, sonar, radar, and tactile sensors) to deduce aspects of the world. Computer vision is the ability to analyze visual input.[58]

The field includes speech recognition,[59] image classification,[60] facial recognition, object recognition,[61]object tracking,[62] and robotic perception.[63]

Social intelligence

Affective computing is an interdisciplinary umbrella that comprises systems that recognize, interpret, process, or simulate human feeling, emotion, and mood.[65] For example, some virtual assistants are programmed to speak conversationally or even to banter humorously; it makes them appear more sensitive to the emotional dynamics of human interaction, or to otherwise facilitate human–computer interaction.

However, this tends to give naïve users an unrealistic conception of the intelligence of existing computer agents.[66] Moderate successes related to affective computing include textual sentiment analysis and, more recently, multimodal sentiment analysis, wherein AI classifies the affects displayed by a videotaped subject.[67]

General intelligence

A machine with artificial general intelligence should be able to solve a wide variety of problems with breadth and versatility similar to human intelligence.[4]

Techniques

AI research uses a wide variety of techniques to accomplish the goals above.[b]

Search and optimization

AI can solve many problems by intelligently searching through many possible solutions.[68] There are two very different kinds of search used in AI: state space search and local search.

State space search

State space search searches through a tree of possible states to try to find a goal state.[69] For example, planning algorithms search through trees of goals and subgoals, attempting to find a path to a target goal, a process called means-ends analysis.[70]

Simple exhaustive searches[71] are rarely sufficient for most real-world problems: the search space (the number of places to search) quickly grows to astronomical numbers. The result is a search that is too slow or never completes.[15] "Heuristics" or "rules of thumb" can help prioritize choices that are more likely to reach a goal.[72]

Adversarial search is used for game-playing programs, such as chess or Go. It searches through a tree of possible moves and counter-moves, looking for a winning position.[73]

Local search

Local search uses mathematical optimization to find a solution to a problem. It begins with some form of guess and refines it incrementally.[74]

Gradient descent is a type of local search that optimizes a set of numerical parameters by incrementally adjusting them to minimize a loss function. Variants of gradient descent are commonly used to train neural networks.[75]

Another type of local search is evolutionary computation, which aims to iteratively improve a set of candidate solutions by "mutating" and "recombining" them, selecting only the fittest to survive each generation.[76]

Distributed search processes can coordinate via swarm intelligence algorithms. Two popular swarm algorithms used in search are particle swarm optimization (inspired by bird flocking) and ant colony optimization (inspired by ant trails).[77]

Logic

Formal logic is used for reasoning and knowledge representation.[78] Formal logic comes in two main forms: propositional logic (which operates on statements that are true or false and uses logical connectives such as "and", "or", "not" and "implies")[79] and predicate logic (which also operates on objects, predicates and relations and uses quantifiers such as "Every X is a Y" and "There are some Xs that are Ys").[80]

Deductive reasoning in logic is the process of proving a new statement (conclusion) from other statements that are given and assumed to be true (the premises).[81] Proofs can be structured as proof trees, in which nodes are labelled by sentences, and children nodes are connected to parent nodes by inference rules.

Given a problem and a set of premises, problem-solving reduces to searching for a proof tree whose root node is labelled by a solution of the problem and whose leaf nodes are labelled by premises or axioms. In the case of Horn clauses, problem-solving search can be performed by reasoning forwards from the premises or backwards from the problem.[82] In the more general case of the clausal form of first-order logic, resolution is a single, axiom-free rule of inference, in which a problem is solved by proving a contradiction from premises that include the negation of the problem to be solved.[83]

Inference in both Horn clause logic and first-order logic is undecidable, and therefore intractable. However, backward reasoning with Horn clauses, which underpins computation in the logic programming language Prolog, is Turing complete. Moreover, its efficiency is competitive with computation in other symbolic programming languages.[84]

Fuzzy logic assigns a "degree of truth" between 0 and 1. It can therefore handle propositions that are vague and partially true.[85]

Non-monotonic logics, including logic programming with negation as failure, are designed to handle default reasoning.[28] Other specialized versions of logic have been developed to describe many complex domains.

Probabilistic methods for uncertain reasoning

Many problems in AI (including in reasoning, planning, learning, perception, and robotics) require the agent to operate with incomplete or uncertain information. AI researchers have devised a number of tools to solve these problems using methods from probability theory and economics.[86] Precise mathematical tools have been developed that analyze how an agent can make choices and plan, using decision theory, decision analysis,[87] and information value theory.[88] These tools include models such as Markov decision processes,[89] dynamic decision networks,[90] game theory and mechanism design.[91]

Bayesian networks[92] are a tool that can be used for reasoning (using the Bayesian inference algorithm),[g][94] learning (using the expectation–maximization algorithm),[h][96] planning (using decision networks)[97] and perception (using dynamic Bayesian networks).[90]

Probabilistic algorithms can also be used for filtering, prediction, smoothing, and finding explanations for streams of data, thus helping perception systems analyze processes that occur over time (e.g., hidden Markov models or Kalman filters).[90]

Classifiers and statistical learning methods

The simplest AI applications can be divided into two types: classifiers (e.g., "if shiny then diamond"), on one hand, and controllers (e.g., "if diamond then pick up"), on the other hand. Classifiers[98] are functions that use pattern matching to determine the closest match. They can be fine-tuned based on chosen examples using supervised learning. Each pattern (also called an "observation") is labeled with a certain predefined class. All the observations combined with their class labels are known as a data set. When a new observation is received, that observation is classified based on previous experience.[45]

There are many kinds of classifiers in use.[99] The decision tree is the simplest and most widely used symbolic machine learning algorithm.[100] K-nearest neighbor algorithm was the most widely used analogical AI until the mid-1990s, and Kernel methods such as the support vector machine (SVM) displaced k-nearest neighbor in the 1990s.[101] The naive Bayes classifier is reportedly the "most widely used learner"[102] at Google, due in part to its scalability.[103] Neural networks are also used as classifiers.[104]

Artificial neural networks

An artificial neural network is based on a collection of nodes also known as artificial neurons, which loosely model the neurons in a biological brain. It is trained to recognise patterns; once trained, it can recognise those patterns in fresh data. There is an input, at least one hidden layer of nodes and an output. Each node applies a function and once the weight crosses its specified threshold, the data is transmitted to the next layer. A network is typically called a deep neural network if it has at least 2 hidden layers.[104]

Learning algorithms for neural networks use local search to choose the weights that will get the right output for each input during training. The most common training technique is the backpropagation algorithm.[105] Neural networks learn to model complex relationships between inputs and outputs and find patterns in data. In theory, a neural network can learn any function.[106]

In feedforward neural networks the signal passes in only one direction.[107] Recurrent neural networks feed the output signal back into the input, which allows short-term memories of previous input events. Long short term memory is the most successful network architecture for recurrent networks.[108] Perceptrons[109] use only a single layer of neurons; deep learning[110] uses multiple layers. Convolutional neural networks strengthen the connection between neurons that are "close" to each other—this is especially important in image processing, where a local set of neurons must identify an "edge" before the network can identify an object.[111]

Deep learning

Deep learning[110] uses several layers of neurons between the network's inputs and outputs. The multiple layers can progressively extract higher-level features from the raw input. For example, in image processing, lower layers may identify edges, while higher layers may identify the concepts relevant to a human such as digits, letters, or faces.[112]

Deep learning has profoundly improved the performance of programs in many important subfields of artificial intelligence, including computer vision, speech recognition, natural language processing, image classification,[113] and others. The reason that deep learning performs so well in so many applications is not known as of 2023.[114] The sudden success of deep learning in 2012–2015 did not occur because of some new discovery or theoretical breakthrough (deep neural networks and backpropagation had been described by many people, as far back as the 1950s)[i] but because of two factors: the incredible increase in computer power (including the hundred-fold increase in speed by switching to GPUs) and the availability of vast amounts of training data, especially the giant curated datasets used for benchmark testing, such as ImageNet.[j]

GPT

Generative pre-trained transformers (GPT) are large language models (LLMs) that generate text based on the semantic relationships between words in sentences. Text-based GPT models are pretrained on a large corpus of text that can be from the Internet. The pretraining consists of predicting the next token (a token being usually a word, subword, or punctuation). Throughout this pretraining, GPT models accumulate knowledge about the world and can then generate human-like text by repeatedly predicting the next token. Typically, a subsequent training phase makes the model more truthful, useful, and harmless, usually with a technique called reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). Current GPT models are prone to generating falsehoods called "hallucinations", although this can be reduced with RLHF and quality data. They are used in chatbots, which allow people to ask a question or request a task in simple text.[122][123]

Current models and services include Gemini (formerly Bard), ChatGPT, Grok, Claude, Copilot, and LLaMA.[124] Multimodal GPT models can process different types of data (modalities) such as images, videos, sound, and text.[125]

Hardware and software

In the late 2010s, graphics processing units (GPUs) that were increasingly designed with AI-specific enhancements and used with specialized TensorFlow software had replaced previously used central processing unit (CPUs) as the dominant means for large-scale (commercial and academic) machine learning models' training.[126] Specialized programming languages such as Prolog were used in early AI research,[127] but general-purpose programming languages like Python have become predominant.[128]

The transistor density in integrated circuits has been observed to roughly double every 18 months—a trend known as Moore's law, named after the Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, who first identified it. Improvements in GPUs have been even faster.[129]

Applications

AI and machine learning technology is used in most of the essential applications of the 2020s, including: search engines (such as Google Search), targeting online advertisements, recommendation systems (offered by Netflix, YouTube or Amazon), driving internet traffic, targeted advertising (AdSense, Facebook), virtual assistants (such as Siri or Alexa), autonomous vehicles (including drones, ADAS and self-driving cars), automatic language translation (Microsoft Translator, Google Translate), facial recognition (Apple's Face ID or Microsoft's DeepFace and Google's FaceNet) and image labeling (used by Facebook, Apple's iPhoto and TikTok). The deployment of AI may be overseen by a Chief automation officer (CAO).

Health and medicine

The application of AI in medicine and medical research has the potential to increase patient care and quality of life.[130] Through the lens of the Hippocratic Oath, medical professionals are ethically compelled to use AI, if applications can more accurately diagnose and treat patients.[131][132]

For medical research, AI is an important tool for processing and integrating big data. This is particularly important for organoid and tissue engineering development which use microscopy imaging as a key technique in fabrication.[133] It has been suggested that AI can overcome discrepancies in funding allocated to different fields of research.[133] New AI tools can deepen the understanding of biomedically relevant pathways. For example, AlphaFold 2 (2021) demonstrated the ability to approximate, in hours rather than months, the 3D structure of a protein.[134] In 2023, it was reported that AI-guided drug discovery helped find a class of antibiotics capable of killing two different types of drug-resistant bacteria.[135] In 2024, researchers used machine learning to accelerate the search for Parkinson's disease drug treatments. Their aim was to identify compounds that block the clumping, or aggregation, of alpha-synuclein (the protein that characterises Parkinson's disease). They were able to speed up the initial screening process ten-fold and reduce the cost by a thousand-fold.[136][137]

Games

Game playing programs have been used since the 1950s to demonstrate and test AI's most advanced techniques.[138] Deep Blue became the first computer chess-playing system to beat a reigning world chess champion, Garry Kasparov, on 11 May 1997.[139] In 2011, in a Jeopardy! quiz show exhibition match, IBM's question answering system, Watson, defeated the two greatest Jeopardy! champions, Brad Rutter and Ken Jennings, by a significant margin.[140] In March 2016, AlphaGo won 4 out of 5 games of Go in a match with Go champion Lee Sedol, becoming the first computer Go-playing system to beat a professional Go player without handicaps. Then, in 2017, it defeated Ke Jie, who was the best Go player in the world.[141] Other programs handle imperfect-information games, such as the poker-playing program Pluribus.[142] DeepMind developed increasingly generalistic reinforcement learning models, such as with MuZero, which could be trained to play chess, Go, or Atari games.[143] In 2019, DeepMind's AlphaStar achieved grandmaster level in StarCraft II, a particularly challenging real-time strategy game that involves incomplete knowledge of what happens on the map.[144] In 2021, an AI agent competed in a PlayStation Gran Turismo competition, winning against four of the world's best Gran Turismo drivers using deep reinforcement learning.[145] In 2024, Google DeepMind introduced SIMA, a type of AI capable of autonomously playing nine previously unseen open-world video games by observing screen output, as well as executing short, specific tasks in response to natural language instructions.[146]

Mathematics

In mathematics, special forms of formal step-by-step reasoning are used. In contrast, LLMs such as GPT-4 Turbo, Gemini Ultra, Claude Opus, LLaMa-2 or Mistral Large are working with probabilistic models, which can produce wrong answers in the form of hallucinations. Therefore, they need not only a large database of mathematical problems to learn from but also methods such as supervised fine-tuning or trained classifiers with human-annotated data to improve answers for new problems and learn from corrections.[147] A 2024 study showed that the performance of some language models for reasoning capabilities in solving math problems not included in their training data was low, even for problems with only minor deviations from trained data.[148]

Alternatively, dedicated models for mathematic problem solving with higher precision for the outcome including proof of theorems have been developed such as Alpha Tensor, Alpha Geometry and Alpha Proof all from Google DeepMind,[149] Llemma from eleuther[150] or Julius.[151]

When natural language is used to describe mathematical problems, converters transform such prompts into a formal language such as Lean to define mathematic tasks.

Some models have been developed to solve challenging problems and reach good results in benchmark tests, others to serve as educational tools in mathematics.[152]

Finance

Finance is one of the fastest growing sectors where applied AI tools are being deployed: from retail online banking to investment advice and insurance, where automated "robot advisers" have been in use for some years.[153]

World Pensions experts like Nicolas Firzli insist it may be too early to see the emergence of highly innovative AI-informed financial products and services: "the deployment of AI tools will simply further automatise things: destroying tens of thousands of jobs in banking, financial planning, and pension advice in the process, but I'm not sure it will unleash a new wave of [e.g., sophisticated] pension innovation."[154]

Military

Various countries are deploying AI military applications.[155] The main applications enhance command and control, communications, sensors, integration and interoperability.[156] Research is targeting intelligence collection and analysis, logistics, cyber operations, information operations, and semiautonomous and autonomous vehicles.[155] AI technologies enable coordination of sensors and effectors, threat detection and identification, marking of enemy positions, target acquisition, coordination and deconfliction of distributed Joint Fires between networked combat vehicles involving manned and unmanned teams.[156] AI was incorporated into military operations in Iraq and Syria.[155]

In November 2023, US Vice President Kamala Harris disclosed a declaration signed by 31 nations to set guardrails for the military use of AI. The commitments include using legal reviews to ensure the compliance of military AI with international laws, and being cautious and transparent in the development of this technology.[157]

Generative AI

In the early 2020s, generative AI gained widespread prominence. GenAI is AI capable of generating text, images, videos, or other data using generative models,[158][159] often in response to prompts.[160][161]

In March 2023, 58% of U.S. adults had heard about ChatGPT and 14% had tried it.[162] The increasing realism and ease-of-use of AI-based text-to-image generators such as Midjourney, DALL-E, and Stable Diffusion sparked a trend of viral AI-generated photos. Widespread attention was gained by a fake photo of Pope Francis wearing a white puffer coat, the fictional arrest of Donald Trump, and a hoax of an attack on the Pentagon, as well as the usage in professional creative arts.[163][164]

Agents

Artificial intelligent (AI) agents are software entities designed to perceive their environment, make decisions, and take actions autonomously to achieve specific goals. These agents can interact with users, their environment, or other agents. AI agents are used in various applications, including virtual assistants, chatbots, autonomous vehicles, game-playing systems, and industrial robotics. AI agents operate within the constraints of their programming, available computational resources, and hardware limitations. This means they are restricted to performing tasks within their defined scope and have finite memory and processing capabilities. In real-world applications, AI agents often face time constraints for decision-making and action execution. Many AI agents incorporate learning algorithms, enabling them to improve their performance over time through experience or training. Using machine learning, AI agents can adapt to new situations and optimise their behaviour for their designated tasks.[165][166][167]

Other industry-specific tasks

There are also thousands of successful AI applications used to solve specific problems for specific industries or institutions. In a 2017 survey, one in five companies reported having incorporated "AI" in some offerings or processes.[168] A few examples are energy storage, medical diagnosis, military logistics, applications that predict the result of judicial decisions, foreign policy, or supply chain management.

AI applications for evacuation and disaster management are growing. AI has been used to investigate if and how people evacuated in large scale and small scale evacuations using historical data from GPS, videos or social media. Further, AI can provide real time information on the real time evacuation conditions.[169][170][171]

In agriculture, AI has helped farmers identify areas that need irrigation, fertilization, pesticide treatments or increasing yield. Agronomists use AI to conduct research and development. AI has been used to predict the ripening time for crops such as tomatoes, monitor soil moisture, operate agricultural robots, conduct predictive analytics, classify livestock pig call emotions, automate greenhouses, detect diseases and pests, and save water.

Artificial intelligence is used in astronomy to analyze increasing amounts of available data and applications, mainly for "classification, regression, clustering, forecasting, generation, discovery, and the development of new scientific insights." For example, it is used for discovering exoplanets, forecasting solar activity, and distinguishing between signals and instrumental effects in gravitational wave astronomy. Additionally, it could be used for activities in space, such as space exploration, including the analysis of data from space missions, real-time science decisions of spacecraft, space debris avoidance, and more autonomous operation.

During the 2024 Indian elections, US$50 millions was spent on authorized AI-generated content, notably by creating deepfakes of allied (including sometimes deceased) politicians to better engage with voters, and by translating speeches to various local languages.[172]

Ethics

AI has potential benefits and potential risks.[173] AI may be able to advance science and find solutions for serious problems: Demis Hassabis of Deep Mind hopes to "solve intelligence, and then use that to solve everything else".[174] However, as the use of AI has become widespread, several unintended consequences and risks have been identified.[175] In-production systems can sometimes not factor ethics and bias into their AI training processes, especially when the AI algorithms are inherently unexplainable in deep learning.[176]

Risks and harm

Privacy and copyright

Machine learning algorithms require large amounts of data. The techniques used to acquire this data have raised concerns about privacy, surveillance and copyright.

AI-powered devices and services, such as virtual assistants and IoT products, continuously collect personal information, raising concerns about intrusive data gathering and unauthorized access by third parties. The loss of privacy is further exacerbated by AI's ability to process and combine vast amounts of data, potentially leading to a surveillance society where individual activities are constantly monitored and analyzed without adequate safeguards or transparency.

Sensitive user data collected may include online activity records, geolocation data, video or audio.[177] For example, in order to build speech recognition algorithms, Amazon has recorded millions of private conversations and allowed temporary workers to listen to and transcribe some of them.[178] Opinions about this widespread surveillance range from those who see it as a necessary evil to those for whom it is clearly unethical and a violation of the right to privacy.[179]

AI developers argue that this is the only way to deliver valuable applications. and have developed several techniques that attempt to preserve privacy while still obtaining the data, such as data aggregation, de-identification and differential privacy.[180] Since 2016, some privacy experts, such as Cynthia Dwork, have begun to view privacy in terms of fairness. Brian Christian wrote that experts have pivoted "from the question of 'what they know' to the question of 'what they're doing with it'."[181]

Generative AI is often trained on unlicensed copyrighted works, including in domains such as images or computer code; the output is then used under the rationale of "fair use". Experts disagree about how well and under what circumstances this rationale will hold up in courts of law; relevant factors may include "the purpose and character of the use of the copyrighted work" and "the effect upon the potential market for the copyrighted work".[182][183] Website owners who do not wish to have their content scraped can indicate it in a "robots.txt" file.[184] In 2023, leading authors (including John Grisham and Jonathan Franzen) sued AI companies for using their work to train generative AI.[185][186] Another discussed approach is to envision a separate sui generis system of protection for creations generated by AI to ensure fair attribution and compensation for human authors.[187]

Dominance by tech giants

The commercial AI scene is dominated by Big Tech companies such as Alphabet Inc., Amazon, Apple Inc., Meta Platforms, and Microsoft.[188][189][190] Some of these players already own the vast majority of existing cloud infrastructure and computing power from data centers, allowing them to entrench further in the marketplace.[191][192]

Power needs and environmental impacts

In January 2024, the International Energy Agency (IEA) released Electricity 2024, Analysis and Forecast to 2026, forecasting electric power use.[193] This is the first IEA report to make projections for data centers and power consumption for artificial intelligence and cryptocurrency. The report states that power demand for these uses might double by 2026, with additional electric power usage equal to electricity used by the whole Japanese nation.[194]

Prodigious power consumption by AI is responsible for the growth of fossil fuels use, and might delay closings of obsolete, carbon-emitting coal energy facilities. There is a feverish rise in the construction of data centers throughout the US, making large technology firms (e.g., Microsoft, Meta, Google, Amazon) into voracious consumers of electric power. Projected electric consumption is so immense that there is concern that it will be fulfilled no matter the source. A ChatGPT search involves the use of 10 times the electrical energy as a Google search. The large firms are in haste to find power sources – from nuclear energy to geothermal to fusion. The tech firms argue that – in the long view – AI will be eventually kinder to the environment, but they need the energy now. AI makes the power grid more efficient and "intelligent", will assist in the growth of nuclear power, and track overall carbon emissions, according to technology firms.[195]

A 2024 Goldman Sachs Research Paper, AI Data Centers and the Coming US Power Demand Surge, found "US power demand (is) likely to experience growth not seen in a generation...." and forecasts that, by 2030, US data centers will consume 8% of US power, as opposed to 3% in 2022, presaging growth for the electrical power generation industry by a variety of means.[196] Data centers' need for more and more electrical power is such that they might max out the electrical grid. The Big Tech companies counter that AI can be used to maximize the utilization of the grid by all.[197]

In 2024, the Wall Street Journal reported that big AI companies have begun negotiations with the US nuclear power providers to provide electricity to the data centers. In March 2024 Amazon purchased a Pennsylvania nuclear-powered data center for $650 Million (US).[198] Nvidia CEO Jen-Hsun Huang said nuclear power is a good option for the data centers.[199]

In September 2024, Microsoft announced an agreement with Constellation Energy to re-open the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant to provide Microsoft with 100% of all electric power produced by the plant for 20 years. Reopening the plant, which suffered a partial nuclear meltdown of its Unit 2 reactor in 1979, will require Constellation to get through strict regulatory processes which will include extensive safety scrutiny from the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. If approved (this will be the first ever US re-commissioning of a nuclear plant), over 835 megawatts of power – enough for 800,000 homes – of energy will be produced. The cost for re-opening and upgrading is estimated at $1.6 billion (US) and is dependent on tax breaks for nuclear power contained in the 2022 US Inflation Reduction Act.[200] The US government and the state of Michigan are investing almost $2 billion (US) to reopen the Palisades Nuclear reactor on Lake Michigan. Closed since 2022, the plant is planned to be reopened in October 2025. The Three Mile Island facility will be renamed the Crane Clean Energy Center after Chris Crane, a nuclear proponent and former CEO of Exelon who was responsible for Exelon spinoff of Constellation.[201]

After the last approval in September 2023, Taiwan suspended the approval of data centers north of Taoyuan with a capacity of more than 5 MW in 2024, due to power supply shortages.[202] Taiwan aims to phase out nuclear power by 2025.[202] On the other hand, Singapore imposed a ban on the opening of data centers in 2019 due to electric power, but in 2022, lifted this ban.[202]

Although most nuclear plants in Japan have been shut down after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident, according to an October 2024 Bloomberg article in Japanese, cloud gaming services company Ubitus, in which Nvidia has a stake, is looking for land in Japan near nuclear power plant for a new data center for generative AI.[203] Ubitus CEO Wesley Kuo said nuclear power plants are the most efficient, cheap and stable power for AI.[203]

On 1 November 2024, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) rejected an application submitted by Talen Energy for approval to supply some electricity from the nuclear power station Susquehanna to Amazon's data center.[204] According to the Commission Chairman Willie L. Phillips, it is a burden on the electricity grid as well as a significant cost shifting concern to households and other business sectors.[204]

Misinformation

YouTube, Facebook and others use recommender systems to guide users to more content. These AI programs were given the goal of maximizing user engagement (that is, the only goal was to keep people watching). The AI learned that users tended to choose misinformation, conspiracy theories, and extreme partisan content, and, to keep them watching, the AI recommended more of it. Users also tended to watch more content on the same subject, so the AI led people into filter bubbles where they received multiple versions of the same misinformation.[205] This convinced many users that the misinformation was true, and ultimately undermined trust in institutions, the media and the government.[206] The AI program had correctly learned to maximize its goal, but the result was harmful to society. After the U.S. election in 2016, major technology companies took steps to mitigate the problem [citation needed].

In 2022, generative AI began to create images, audio, video and text that are indistinguishable from real photographs, recordings, films, or human writing. It is possible for bad actors to use this technology to create massive amounts of misinformation or propaganda.[207] AI pioneer Geoffrey Hinton expressed concern about AI enabling "authoritarian leaders to manipulate their electorates" on a large scale, among other risks.[208]

Algorithmic bias and fairness

Machine learning applications will be biased[k] if they learn from biased data.[210] The developers may not be aware that the bias exists.[211] Bias can be introduced by the way training data is selected and by the way a model is deployed.[212][210] If a biased algorithm is used to make decisions that can seriously harm people (as it can in medicine, finance, recruitment, housing or policing) then the algorithm may cause discrimination.[213] The field of fairness studies how to prevent harms from algorithmic biases.

On June 28, 2015, Google Photos's new image labeling feature mistakenly identified Jacky Alcine and a friend as "gorillas" because they were black. The system was trained on a dataset that contained very few images of black people,[214] a problem called "sample size disparity".[215] Google "fixed" this problem by preventing the system from labelling anything as a "gorilla". Eight years later, in 2023, Google Photos still could not identify a gorilla, and neither could similar products from Apple, Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon.[216]

COMPAS is a commercial program widely used by U.S. courts to assess the likelihood of a defendant becoming a recidivist. In 2016, Julia Angwin at ProPublica discovered that COMPAS exhibited racial bias, despite the fact that the program was not told the races of the defendants. Although the error rate for both whites and blacks was calibrated equal at exactly 61%, the errors for each race were different—the system consistently overestimated the chance that a black person would re-offend and would underestimate the chance that a white person would not re-offend.[217] In 2017, several researchers[l] showed that it was mathematically impossible for COMPAS to accommodate all possible measures of fairness when the base rates of re-offense were different for whites and blacks in the data.[219]

A program can make biased decisions even if the data does not explicitly mention a problematic feature (such as "race" or "gender"). The feature will correlate with other features (like "address", "shopping history" or "first name"), and the program will make the same decisions based on these features as it would on "race" or "gender".[220] Moritz Hardt said "the most robust fact in this research area is that fairness through blindness doesn't work."[221]

Criticism of COMPAS highlighted that machine learning models are designed to make "predictions" that are only valid if we assume that the future will resemble the past. If they are trained on data that includes the results of racist decisions in the past, machine learning models must predict that racist decisions will be made in the future. If an application then uses these predictions as recommendations, some of these "recommendations" will likely be racist.[222] Thus, machine learning is not well suited to help make decisions in areas where there is hope that the future will be better than the past. It is descriptive rather than prescriptive.[m]

Bias and unfairness may go undetected because the developers are overwhelmingly white and male: among AI engineers, about 4% are black and 20% are women.[215]

There are various conflicting definitions and mathematical models of fairness. These notions depend on ethical assumptions, and are influenced by beliefs about society. One broad category is distributive fairness, which focuses on the outcomes, often identifying groups and seeking to compensate for statistical disparities. Representational fairness tries to ensure that AI systems do not reinforce negative stereotypes or render certain groups invisible. Procedural fairness focuses on the decision process rather than the outcome. The most relevant notions of fairness may depend on the context, notably the type of AI application and the stakeholders. The subjectivity in the notions of bias and fairness makes it difficult for companies to operationalize them. Having access to sensitive attributes such as race or gender is also considered by many AI ethicists to be necessary in order to compensate for biases, but it may conflict with anti-discrimination laws.[209]

At its 2022 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (ACM FAccT 2022), the Association for Computing Machinery, in Seoul, South Korea, presented and published findings that recommend that until AI and robotics systems are demonstrated to be free of bias mistakes, they are unsafe, and the use of self-learning neural networks trained on vast, unregulated sources of flawed internet data should be curtailed.[dubious – discuss][224]

Lack of transparency

Many AI systems are so complex that their designers cannot explain how they reach their decisions.[225] Particularly with deep neural networks, in which there are a large amount of non-linear relationships between inputs and outputs. But some popular explainability techniques exist.[226]

It is impossible to be certain that a program is operating correctly if no one knows how exactly it works. There have been many cases where a machine learning program passed rigorous tests, but nevertheless learned something different than what the programmers intended. For example, a system that could identify skin diseases better than medical professionals was found to actually have a strong tendency to classify images with a ruler as "cancerous", because pictures of malignancies typically include a ruler to show the scale.[227] Another machine learning system designed to help effectively allocate medical resources was found to classify patients with asthma as being at "low risk" of dying from pneumonia. Having asthma is actually a severe risk factor, but since the patients having asthma would usually get much more medical care, they were relatively unlikely to die according to the training data. The correlation between asthma and low risk of dying from pneumonia was real, but misleading.[228]

People who have been harmed by an algorithm's decision have a right to an explanation.[229] Doctors, for example, are expected to clearly and completely explain to their colleagues the reasoning behind any decision they make. Early drafts of the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation in 2016 included an explicit statement that this right exists.[n] Industry experts noted that this is an unsolved problem with no solution in sight. Regulators argued that nevertheless the harm is real: if the problem has no solution, the tools should not be used.[230]

DARPA established the XAI ("Explainable Artificial Intelligence") program in 2014 to try to solve these problems.[231]

Several approaches aim to address the transparency problem. SHAP enables to visualise the contribution of each feature to the output.[232] LIME can locally approximate a model's outputs with a simpler, interpretable model.[233] Multitask learning provides a large number of outputs in addition to the target classification. These other outputs can help developers deduce what the network has learned.[234] Deconvolution, DeepDream and other generative methods can allow developers to see what different layers of a deep network for computer vision have learned, and produce output that can suggest what the network is learning.[235] For generative pre-trained transformers, Anthropic developed a technique based on dictionary learning that associates patterns of neuron activations with human-understandable concepts.[236]

Bad actors and weaponized AI

Artificial intelligence provides a number of tools that are useful to bad actors, such as authoritarian governments, terrorists, criminals or rogue states.

A lethal autonomous weapon is a machine that locates, selects and engages human targets without human supervision.[o] Widely available AI tools can be used by bad actors to develop inexpensive autonomous weapons and, if produced at scale, they are potentially weapons of mass destruction.[238] Even when used in conventional warfare, it is unlikely that they will be unable to reliably choose targets and could potentially kill an innocent person.[238] In 2014, 30 nations (including China) supported a ban on autonomous weapons under the United Nations' Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, however the United States and others disagreed.[239] By 2015, over fifty countries were reported to be researching battlefield robots.[240]

AI tools make it easier for authoritarian governments to efficiently control their citizens in several ways. Face and voice recognition allow widespread surveillance. Machine learning, operating this data, can classify potential enemies of the state and prevent them from hiding. Recommendation systems can precisely target propaganda and misinformation for maximum effect. Deepfakes and generative AI aid in producing misinformation. Advanced AI can make authoritarian centralized decision making more competitive than liberal and decentralized systems such as markets. It lowers the cost and difficulty of digital warfare and advanced spyware.[241] All these technologies have been available since 2020 or earlier—AI facial recognition systems are already being used for mass surveillance in China.[242][243]

There many other ways that AI is expected to help bad actors, some of which can not be foreseen. For example, machine-learning AI is able to design tens of thousands of toxic molecules in a matter of hours.[244]

Technological unemployment

Economists have frequently highlighted the risks of redundancies from AI, and speculated about unemployment if there is no adequate social policy for full employment.[245]

In the past, technology has tended to increase rather than reduce total employment, but economists acknowledge that "we're in uncharted territory" with AI.[246] A survey of economists showed disagreement about whether the increasing use of robots and AI will cause a substantial increase in long-term unemployment, but they generally agree that it could be a net benefit if productivity gains are redistributed.[247] Risk estimates vary; for example, in the 2010s, Michael Osborne and Carl Benedikt Frey estimated 47% of U.S. jobs are at "high risk" of potential automation, while an OECD report classified only 9% of U.S. jobs as "high risk".[p][249] The methodology of speculating about future employment levels has been criticised as lacking evidential foundation, and for implying that technology, rather than social policy, creates unemployment, as opposed to redundancies.[245] In April 2023, it was reported that 70% of the jobs for Chinese video game illustrators had been eliminated by generative artificial intelligence.[250][251]

Unlike previous waves of automation, many middle-class jobs may be eliminated by artificial intelligence; The Economist stated in 2015 that "the worry that AI could do to white-collar jobs what steam power did to blue-collar ones during the Industrial Revolution" is "worth taking seriously".[252] Jobs at extreme risk range from paralegals to fast food cooks, while job demand is likely to increase for care-related professions ranging from personal healthcare to the clergy.[253]

From the early days of the development of artificial intelligence, there have been arguments, for example, those put forward by Joseph Weizenbaum, about whether tasks that can be done by computers actually should be done by them, given the difference between computers and humans, and between quantitative calculation and qualitative, value-based judgement.[254]

Existential risk

It has been argued AI will become so powerful that humanity may irreversibly lose control of it. This could, as physicist Stephen Hawking stated, "spell the end of the human race".[255] This scenario has been common in science fiction, when a computer or robot suddenly develops a human-like "self-awareness" (or "sentience" or "consciousness") and becomes a malevolent character.[q] These sci-fi scenarios are misleading in several ways.

First, AI does not require human-like "sentience" to be an existential risk. Modern AI programs are given specific goals and use learning and intelligence to achieve them. Philosopher Nick Bostrom argued that if one gives almost any goal to a sufficiently powerful AI, it may choose to destroy humanity to achieve it (he used the example of a paperclip factory manager).[257] Stuart Russell gives the example of household robot that tries to find a way to kill its owner to prevent it from being unplugged, reasoning that "you can't fetch the coffee if you're dead."[258] In order to be safe for humanity, a superintelligence would have to be genuinely aligned with humanity's morality and values so that it is "fundamentally on our side".[259]

Second, Yuval Noah Harari argues that AI does not require a robot body or physical control to pose an existential risk. The essential parts of civilization are not physical. Things like ideologies, law, government, money and the economy are made of language; they exist because there are stories that billions of people believe. The current prevalence of misinformation suggests that an AI could use language to convince people to believe anything, even to take actions that are destructive.[260]

The opinions amongst experts and industry insiders are mixed, with sizable fractions both concerned and unconcerned by risk from eventual superintelligent AI.[261] Personalities such as Stephen Hawking, Bill Gates, and Elon Musk,[262] as well as AI pioneers such as Yoshua Bengio, Stuart Russell, Demis Hassabis, and Sam Altman, have expressed concerns about existential risk from AI.

In May 2023, Geoffrey Hinton announced his resignation from Google in order to be able to "freely speak out about the risks of AI" without "considering how this impacts Google."[263] He notably mentioned risks of an AI takeover,[264] and stressed that in order to avoid the worst outcomes, establishing safety guidelines will require cooperation among those competing in use of AI.[265]

In 2023, many leading AI experts issued the joint statement that "Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war".[266]

Other researchers, however, spoke in favor of a less dystopian view. AI pioneer Juergen Schmidhuber did not sign the joint statement, emphasising that in 95% of all cases, AI research is about making "human lives longer and healthier and easier."[267] While the tools that are now being used to improve lives can also be used by bad actors, "they can also be used against the bad actors."[268][269] Andrew Ng also argued that "it's a mistake to fall for the doomsday hype on AI—and that regulators who do will only benefit vested interests."[270] Yann LeCun "scoffs at his peers' dystopian scenarios of supercharged misinformation and even, eventually, human extinction."[271] In the early 2010s, experts argued that the risks are too distant in the future to warrant research or that humans will be valuable from the perspective of a superintelligent machine.[272] However, after 2016, the study of current and future risks and possible solutions became a serious area of research.[273]

Ethical machines and alignment

Friendly AI are machines that have been designed from the beginning to minimize risks and to make choices that benefit humans. Eliezer Yudkowsky, who coined the term, argues that developing friendly AI should be a higher research priority: it may require a large investment and it must be completed before AI becomes an existential risk.[274]

Machines with intelligence have the potential to use their intelligence to make ethical decisions. The field of machine ethics provides machines with ethical principles and procedures for resolving ethical dilemmas.[275] The field of machine ethics is also called computational morality,[275] and was founded at an AAAI symposium in 2005.[276]

Other approaches include Wendell Wallach's "artificial moral agents"[277] and Stuart J. Russell's three principles for developing provably beneficial machines.[278]

Open source

Active organizations in the AI open-source community include Hugging Face,[279] Google,[280] EleutherAI and Meta.[281] Various AI models, such as Llama 2, Mistral or Stable Diffusion, have been made open-weight,[282][283] meaning that their architecture and trained parameters (the "weights") are publicly available. Open-weight models can be freely fine-tuned, which allows companies to specialize them with their own data and for their own use-case.[284] Open-weight models are useful for research and innovation but can also be misused. Since they can be fine-tuned, any built-in security measure, such as objecting to harmful requests, can be trained away until it becomes ineffective. Some researchers warn that future AI models may develop dangerous capabilities (such as the potential to drastically facilitate bioterrorism) and that once released on the Internet, they cannot be deleted everywhere if needed. They recommend pre-release audits and cost-benefit analyses.[285]

Frameworks

Artificial Intelligence projects can have their ethical permissibility tested while designing, developing, and implementing an AI system. An AI framework such as the Care and Act Framework containing the SUM values—developed by the Alan Turing Institute tests projects in four main areas:[286][287]

- Respect the dignity of individual people

- Connect with other people sincerely, openly, and inclusively

- Care for the wellbeing of everyone

- Protect social values, justice, and the public interest

Other developments in ethical frameworks include those decided upon during the Asilomar Conference, the Montreal Declaration for Responsible AI, and the IEEE's Ethics of Autonomous Systems initiative, among others;[288] however, these principles do not go without their criticisms, especially regards to the people chosen contributes to these frameworks.[289]

Promotion of the wellbeing of the people and communities that these technologies affect requires consideration of the social and ethical implications at all stages of AI system design, development and implementation, and collaboration between job roles such as data scientists, product managers, data engineers, domain experts, and delivery managers.[290]

The UK AI Safety Institute released in 2024 a testing toolset called 'Inspect' for AI safety evaluations available under a MIT open-source licence which is freely available on GitHub and can be improved with third-party packages. It can be used to evaluate AI models in a range of areas including core knowledge, ability to reason, and autonomous capabilities.[291]

Regulation

The regulation of artificial intelligence is the development of public sector policies and laws for promoting and regulating AI; it is therefore related to the broader regulation of algorithms.[292] The regulatory and policy landscape for AI is an emerging issue in jurisdictions globally.[293] According to AI Index at Stanford, the annual number of AI-related laws passed in the 127 survey countries jumped from one passed in 2016 to 37 passed in 2022 alone.[294][295] Between 2016 and 2020, more than 30 countries adopted dedicated strategies for AI.[296] Most EU member states had released national AI strategies, as had Canada, China, India, Japan, Mauritius, the Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, U.S., and Vietnam. Others were in the process of elaborating their own AI strategy, including Bangladesh, Malaysia and Tunisia.[296] The Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence was launched in June 2020, stating a need for AI to be developed in accordance with human rights and democratic values, to ensure public confidence and trust in the technology.[296] Henry Kissinger, Eric Schmidt, and Daniel Huttenlocher published a joint statement in November 2021 calling for a government commission to regulate AI.[297] In 2023, OpenAI leaders published recommendations for the governance of superintelligence, which they believe may happen in less than 10 years.[298] In 2023, the United Nations also launched an advisory body to provide recommendations on AI governance; the body comprises technology company executives, governments officials and academics.[299] In 2024, the Council of Europe created the first international legally binding treaty on AI, called the "Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence and Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law". It was adopted by the European Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, and other signatories.[300]

In a 2022 Ipsos survey, attitudes towards AI varied greatly by country; 78% of Chinese citizens, but only 35% of Americans, agreed that "products and services using AI have more benefits than drawbacks".[294] A 2023 Reuters/Ipsos poll found that 61% of Americans agree, and 22% disagree, that AI poses risks to humanity.[301] In a 2023 Fox News poll, 35% of Americans thought it "very important", and an additional 41% thought it "somewhat important", for the federal government to regulate AI, versus 13% responding "not very important" and 8% responding "not at all important".[302][303]

In November 2023, the first global AI Safety Summit was held in Bletchley Park in the UK to discuss the near and far term risks of AI and the possibility of mandatory and voluntary regulatory frameworks.[304] 28 countries including the United States, China, and the European Union issued a declaration at the start of the summit, calling for international co-operation to manage the challenges and risks of artificial intelligence.[305][306] In May 2024 at the AI Seoul Summit, 16 global AI tech companies agreed to safety commitments on the development of AI.[307][308]

History

The study of mechanical or "formal" reasoning began with philosophers and mathematicians in antiquity. The study of logic led directly to Alan Turing's theory of computation, which suggested that a machine, by shuffling symbols as simple as "0" and "1", could simulate any conceivable form of mathematical reasoning.[309][310] This, along with concurrent discoveries in cybernetics, information theory and neurobiology, led researchers to consider the possibility of building an "electronic brain".[r] They developed several areas of research that would become part of AI,[312] such as McCullouch and Pitts design for "artificial neurons" in 1943,[115] and Turing's influential 1950 paper 'Computing Machinery and Intelligence', which introduced the Turing test and showed that "machine intelligence" was plausible.[313][310]

The field of AI research was founded at a workshop at Dartmouth College in 1956.[s][6] The attendees became the leaders of AI research in the 1960s.[t] They and their students produced programs that the press described as "astonishing":[u] computers were learning checkers strategies, solving word problems in algebra, proving logical theorems and speaking English.[v][7] Artificial intelligence laboratories were set up at a number of British and U.S. universities in the latter 1950s and early 1960s.[310]

Researchers in the 1960s and the 1970s were convinced that their methods would eventually succeed in creating a machine with general intelligence and considered this the goal of their field.[317] In 1965 Herbert Simon predicted, "machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do".[318] In 1967 Marvin Minsky agreed, writing that "within a generation ... the problem of creating 'artificial intelligence' will substantially be solved".[319] They had, however, underestimated the difficulty of the problem.[w] In 1974, both the U.S. and British governments cut off exploratory research in response to the criticism of Sir James Lighthill[321] and ongoing pressure from the U.S. Congress to fund more productive projects.[322] Minsky's and Papert's book Perceptrons was understood as proving that artificial neural networks would never be useful for solving real-world tasks, thus discrediting the approach altogether.[323] The "AI winter", a period when obtaining funding for AI projects was difficult, followed.[9]

In the early 1980s, AI research was revived by the commercial success of expert systems,[324] a form of AI program that simulated the knowledge and analytical skills of human experts. By 1985, the market for AI had reached over a billion dollars. At the same time, Japan's fifth generation computer project inspired the U.S. and British governments to restore funding for academic research.[8] However, beginning with the collapse of the Lisp Machine market in 1987, AI once again fell into disrepute, and a second, longer-lasting winter began.[10]

Up to this point, most of AI's funding had gone to projects that used high-level symbols to represent mental objects like plans, goals, beliefs, and known facts. In the 1980s, some researchers began to doubt that this approach would be able to imitate all the processes of human cognition, especially perception, robotics, learning and pattern recognition,[325] and began to look into "sub-symbolic" approaches.[326] Rodney Brooks rejected "representation" in general and focussed directly on engineering machines that move and survive.[x] Judea Pearl, Lofti Zadeh and others developed methods that handled incomplete and uncertain information by making reasonable guesses rather than precise logic.[86][331] But the most important development was the revival of "connectionism", including neural network research, by Geoffrey Hinton and others.[332] In 1990, Yann LeCun successfully showed that convolutional neural networks can recognize handwritten digits, the first of many successful applications of neural networks.[333]

AI gradually restored its reputation in the late 1990s and early 21st century by exploiting formal mathematical methods and by finding specific solutions to specific problems. This "narrow" and "formal" focus allowed researchers to produce verifiable results and collaborate with other fields (such as statistics, economics and mathematics).[334] By 2000, solutions developed by AI researchers were being widely used, although in the 1990s they were rarely described as "artificial intelligence" (a tendency known as the AI effect).[335] However, several academic researchers became concerned that AI was no longer pursuing its original goal of creating versatile, fully intelligent machines. Beginning around 2002, they founded the subfield of artificial general intelligence (or "AGI"), which had several well-funded institutions by the 2010s.[4]

Deep learning began to dominate industry benchmarks in 2012 and was adopted throughout the field.[11] For many specific tasks, other methods were abandoned.[y] Deep learning's success was based on both hardware improvements (faster computers,[337] graphics processing units, cloud computing[338]) and access to large amounts of data[339] (including curated datasets,[338] such as ImageNet). Deep learning's success led to an enormous increase in interest and funding in AI.[z] The amount of machine learning research (measured by total publications) increased by 50% in the years 2015–2019.[296]

In 2016, issues of fairness and the misuse of technology were catapulted into center stage at machine learning conferences, publications vastly increased, funding became available, and many researchers re-focussed their careers on these issues. The alignment problem became a serious field of academic study.[273]

In the late teens and early 2020s, AGI companies began to deliver programs that created enormous interest. In 2015, AlphaGo, developed by DeepMind, beat the world champion Go player. The program was taught only the rules of the game and developed strategy by itself. GPT-3 is a large language model that was released in 2020 by OpenAI and is capable of generating high-quality human-like text.[340] These programs, and others, inspired an aggressive AI boom, where large companies began investing billions in AI research. According to AI Impacts, about $50 billion annually was invested in "AI" around 2022 in the U.S. alone and about 20% of the new U.S. Computer Science PhD graduates have specialized in "AI".[341] About 800,000 "AI"-related U.S. job openings existed in 2022.[342]

Philosophy

Philosophical debates have historically sought to determine the nature of intelligence and how to make intelligent machines.[343] Another major focus has been whether machines can be conscious, and the associated ethical implications.[344] Many other topics in philosophy are relevant to AI, such as epistemology and free will.[345] Rapid advancements have intensified public discussions on the philosophy and ethics of AI.[344]

Defining artificial intelligence

Alan Turing wrote in 1950 "I propose to consider the question 'can machines think'?"[346] He advised changing the question from whether a machine "thinks", to "whether or not it is possible for machinery to show intelligent behaviour".[346] He devised the Turing test, which measures the ability of a machine to simulate human conversation.[313] Since we can only observe the behavior of the machine, it does not matter if it is "actually" thinking or literally has a "mind". Turing notes that we can not determine these things about other people but "it is usual to have a polite convention that everyone thinks."[347]

Russell and Norvig agree with Turing that intelligence must be defined in terms of external behavior, not internal structure.[1] However, they are critical that the test requires the machine to imitate humans. "Aeronautical engineering texts," they wrote, "do not define the goal of their field as making 'machines that fly so exactly like pigeons that they can fool other pigeons.'"[349] AI founder John McCarthy agreed, writing that "Artificial intelligence is not, by definition, simulation of human intelligence".[350]

McCarthy defines intelligence as "the computational part of the ability to achieve goals in the world".[351] Another AI founder, Marvin Minsky similarly describes it as "the ability to solve hard problems".[352] The leading AI textbook defines it as the study of agents that perceive their environment and take actions that maximize their chances of achieving defined goals.[1] These definitions view intelligence in terms of well-defined problems with well-defined solutions, where both the difficulty of the problem and the performance of the program are direct measures of the "intelligence" of the machine—and no other philosophical discussion is required, or may not even be possible.

Another definition has been adopted by Google,[353] a major practitioner in the field of AI. This definition stipulates the ability of systems to synthesize information as the manifestation of intelligence, similar to the way it is defined in biological intelligence.

Some authors have suggested in practice, that the definition of AI is vague and difficult to define, with contention as to whether classical algorithms should be categorised as AI,[354] with many companies during the early 2020s AI boom using the term as a marketing buzzword, often even if they did "not actually use AI in a material way".[355]

Evaluating approaches to AI

No established unifying theory or paradigm has guided AI research for most of its history.[aa] The unprecedented success of statistical machine learning in the 2010s eclipsed all other approaches (so much so that some sources, especially in the business world, use the term "artificial intelligence" to mean "machine learning with neural networks"). This approach is mostly sub-symbolic, soft and narrow. Critics argue that these questions may have to be revisited by future generations of AI researchers.

Symbolic AI and its limits

Symbolic AI (or "GOFAI")[357] simulated the high-level conscious reasoning that people use when they solve puzzles, express legal reasoning and do mathematics. They were highly successful at "intelligent" tasks such as algebra or IQ tests. In the 1960s, Newell and Simon proposed the physical symbol systems hypothesis: "A physical symbol system has the necessary and sufficient means of general intelligent action."[358]

However, the symbolic approach failed on many tasks that humans solve easily, such as learning, recognizing an object or commonsense reasoning. Moravec's paradox is the discovery that high-level "intelligent" tasks were easy for AI, but low level "instinctive" tasks were extremely difficult.[359] Philosopher Hubert Dreyfus had argued since the 1960s that human expertise depends on unconscious instinct rather than conscious symbol manipulation, and on having a "feel" for the situation, rather than explicit symbolic knowledge.[360] Although his arguments had been ridiculed and ignored when they were first presented, eventually, AI research came to agree with him.[ab][16]

The issue is not resolved: sub-symbolic reasoning can make many of the same inscrutable mistakes that human intuition does, such as algorithmic bias. Critics such as Noam Chomsky argue continuing research into symbolic AI will still be necessary to attain general intelligence,[362][363] in part because sub-symbolic AI is a move away from explainable AI: it can be difficult or impossible to understand why a modern statistical AI program made a particular decision. The emerging field of neuro-symbolic artificial intelligence attempts to bridge the two approaches.

Neat vs. scruffy

"Neats" hope that intelligent behavior is described using simple, elegant principles (such as logic, optimization, or neural networks). "Scruffies" expect that it necessarily requires solving a large number of unrelated problems. Neats defend their programs with theoretical rigor, scruffies rely mainly on incremental testing to see if they work. This issue was actively discussed in the 1970s and 1980s,[364] but eventually was seen as irrelevant. Modern AI has elements of both.

Soft vs. hard computing

Finding a provably correct or optimal solution is intractable for many important problems.[15] Soft computing is a set of techniques, including genetic algorithms, fuzzy logic and neural networks, that are tolerant of imprecision, uncertainty, partial truth and approximation. Soft computing was introduced in the late 1980s and most successful AI programs in the 21st century are examples of soft computing with neural networks.

Narrow vs. general AI

AI researchers are divided as to whether to pursue the goals of artificial general intelligence and superintelligence directly or to solve as many specific problems as possible (narrow AI) in hopes these solutions will lead indirectly to the field's long-term goals.[365][366] General intelligence is difficult to define and difficult to measure, and modern AI has had more verifiable successes by focusing on specific problems with specific solutions. The sub-field of artificial general intelligence studies this area exclusively.

Machine consciousness, sentience, and mind

The philosophy of mind does not know whether a machine can have a mind, consciousness and mental states, in the same sense that human beings do. This issue considers the internal experiences of the machine, rather than its external behavior. Mainstream AI research considers this issue irrelevant because it does not affect the goals of the field: to build machines that can solve problems using intelligence. Russell and Norvig add that "[t]he additional project of making a machine conscious in exactly the way humans are is not one that we are equipped to take on."[367] However, the question has become central to the philosophy of mind. It is also typically the central question at issue in artificial intelligence in fiction.

Consciousness