Ibn Saud: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

|birth_date = 15 January 1876 |

|birth_date = 15 January 1876 |

||

|birth_place = [[Riyadh]], [[Second Saudi State]] |

|birth_place = [[Riyadh]], [[Second Saudi State]] |

||

|death_date = 9 November 1953 ( |

|death_date = 9 November 1953 (dmy) |

||

|death_place = [[Taif]] |

|death_place = [[Taif]] |

||

|date of burial = |

|date of burial = |

||

Revision as of 08:30, 20 May 2013

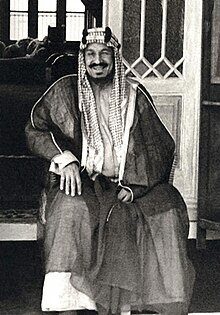

Template:Contains Arabic text King Abdulaziz (15 January 1876[1] – 9 November 1953) (Template:Lang-ar ‘Abd al-‘Azīz Āl Sa‘ūd) was the first monarch of Saudi Arabia, the third Saudi State.[2] He was referred to for most of his career as Ibn Saud.[3]

Beginning with the reconquest of his family's ancestral home city of Riyadh in 1902, he consolidated his control over the Najd in 1922, then conquered the Hijaz in 1925. Having conquered almost all of central Arabia, he united his dominions into the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932. As King, he presided over the discovery of petroleum in Saudi Arabia in 1938 and the beginning of large-scale oil exploitation after World War II. He was the father of many children having 45 sons,[4] including all of the subsequent kings of Saudi Arabia.

Early life

King Abdulaziz was born on 15 January 1876 in Riyadh, in the region of Najd in central Arabia.[5] Ibn Saud's mother was a Sudairi,[6] Sarah al Sudairi (died 1910).[7] In 1890, the Al Rashid conquered Riyadh. Abdulaziz was 15 at the time.[8] He and his family initially took refuge with the Al-Murrah, a Bedouin tribe in the southern desert of Saudi Arabia. Later, the Al Sauds moved to Kuwait.

Abdulaziz lived with his family in a simple dwelling. His primary occupation, and the family's sole source of income, was undertaking raids in the Najd. He also attended the daily majlis of the emir of Kuwait, Mubarak Al-Sabah, from whom he learned the art of statecraft.[citation needed]

In the spring of 1901, he and some relatives – including a half-brother, Mohammed, and several cousins – set out on a raiding expedition into the Najd, targeting for the most part tribes associated with the Rashidis. As the raid proved profitable, it attracted more participants. The raiders' numbers peaked at over 200, though these numbers dwindled over the ensuing months.[citation needed]

In the autumn, the group made camp in the Yabrin oasis. While observing Ramadan, he decided to attack Riyadh and retake it from the Al Rashidi. On the night of 15 January 1902, he led 40 men over the walls of the city on tilted palm trees and took the city.[9] The Rashidi governor of the city, Ajlan, was killed in front of his own fortress. The Saudi recapture of the city marked the beginning of the Third Saudi State.

Rise to power

Following the capture of Riyadh, many former supporters of the House of Saud rallied to Ibn Saud's call to arms. He was a charismatic leader and kept his men supplied with arms. Over the next two years, he and his forces recaptured almost half of the Najd from the Rashidis.

In 1904, Ibn Rashid appealed to the Ottoman Empire for military protection and assistance. The Ottomans responded by sending troops into Arabia. On 15 June 1904, Ibn Saud's forces suffered a major defeat at the hands of the combined Ottoman and Rashidi forces. His forces regrouped and began to wage guerrilla warfare against the Ottomans. Over the next two years he was able to disrupt their supply routes, forcing them to retreat.

He completed his conquest of the Najd and the eastern coast of Arabia in 1912. He then founded the Ikhwan, a military-religious brotherhood which was to assist in his later conquests, with the approval of local Salafi ulema. In the same year, he instituted an agrarian policy to settle the nomadic pastoralist bedouins into colonies, and to dismantle their tribal organizations in favor of allegiance to the Ikhwan.

During World War I, the British government established diplomatic relations with Ibn Saud. The British agent, Captain William Shakespear, was well received by the Bedouin.[10] Similar diplomatic missions were established with any Arabian power who might have been able to unify and stabilize the region. The British entered into a treaty in December 1915 (the "Treaty of Darin") which made the lands of the House of Saud a British protectorate and attempted to define the boundaries of the developing Saudi state.[11] In exchange, Ibn Saud pledged to again make war against Ibn Rashid, who was an ally of the Ottomans.

The British Foreign Office had previously begun to support Sharif Hussein bin Ali, Emir of the Hejaz by seconding Lawrence of Arabia to him in 1915. The Saudi Ikhwan began to conflict with Emir Feisal also in 1917 just as his sons Abdullah and Feisal entered Damascus. The Treaty of Darin remained in effect until superseded by the Jeddah conference of 1927 and the Dammam conference of 1952 during both of which Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud extended his boundaries past the Anglo-Ottoman Blue Line. After Darin, he stockpiled the weapons and supplies with which the British provided him, including a 'tribute' of £5,000 per month.[12] After World War I, he received further support from the British, including a glut of surplus munitions. He launched his campaign against the Al Rashidi in 1920; by 1922 they had been all but destroyed.

The defeat of the Al Rashidi doubled the size of Saudi territory. This allowed Ibn Saud the leverage to negotiate a new and more favorable treaty with the British. Their treaty, signed at Uqair in 1922, saw Britain recognize many of his territorial gains. In exchange, Ibn Saud agreed to recognize British territories in the area, particularly along the Persian Gulf coast and in Iraq. The former of these were vital to the British, as merchant traffic between British India and England depended upon coaling stations on the approach to the Suez Canal.

In 1925 the forces of Ibn Saud captured the holy city of Mecca from Sharif Hussein bin Ali, ending 700 years of Hashemite rule. On 8 January 1926, the leading figures in Mecca, Madina and Jeddah proclaimed Ibn Saud the King of Hejaz.[13] On 20 May 1927, the British government signed the Treaty of Jeddah, which abolished the Darin protection agreement and recognized the independence of the Hejaz and Najd with Ibn Saud as its ruler.

With international recognition and support, Ibn Saud continued to consolidate his power, eventually conquering nearly all of the central Arabian Peninsula. However, the alliance between the Ikhwan and the Al Saud collapsed when Ibn Saud forbade further raiding; the remaining territories all had treaties with London. This didn't sit well with the Ikwhan, who had been taught that all non-Wahhabis were infidels. Tensions finally boiled over when the Ikwhan rebelled in 1927. After two years of fighting, they were suppressed by Ibn Saud in the Battle of Sabilla in March 1929.

On 23 September 1932, Ibn Saud united his dominions into the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with himself as its king.[14]

Ibn Saud had to first eliminate the right of his own father in order to rule, and then distance and contain the ambitions of his five brothers – particularly his oldest brother Muhammad who fought with him during the battles and conquests that had given birth to the state.[15]

Oil and the rule of Ibn Saud

Oil was discovered in Saudi Arabia in 1938 by American geologists working for Standard Oil of California in partnership with Saudi officials. Through his advisers St. John Philby and Ameen Rihani, he granted substantial authority over Saudi oil fields to American oil companies in 1944, much to the dismay of the British who had invested heavily in the House of Saud's rise to power in hopes of open access to any oil reserves that were to be surveyed. Beginning in 1915, Ibn Saud signed the "friendship and cooperation" pact with Britain to keep his militia in line and cease any further attacks against their protectorates for whom they were responsible. Not only did the British pay a generous monthly allowance for his cooperation, but in 1935 he was knighted into the Order of the Bath.

His newfound oil wealth brought with it a great deal of power and influence that, naturally, Ibn Saud would use to advantage in the Hijaz. He forced many nomadic tribes to settle down and abandon "petty wars" and vendettas. He also began widespread enforcement of the new kingdom's ideology, based on the teachings of Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab. This included an end to traditionally sanctioned rites of pilgrimage, recognized by the orthodox schools of jurisprudence, but at odds with those sanctioned by Abd al Wahhab. In 1926, after a caravan of Egyptians on the way to Mecca were beaten by his forces for playing bugles, he was impelled to issue a conciliatory statement to the Egyptian government. In fact, several such statements were issued to Muslim governments around the world as a result of beatings suffered by the pilgrims visiting the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.[citation needed] With the uprising and subsequent decimation thereafter of the Ikhwan in 1929 via British air power, the 1930s marked a turning point. With his rivals eliminated, Ibn Saud's ideology was in full force, ending nearly 1400 years of accepted religious practices surrounding the Hajj, the majority of which were sanctioned by a millennia of scholarship.

Abdulaziz established a Shura Council of the Hijaz as early as 1927. This Council was later expanded to 20 members, and was chaired by the king's son, Faisal.[16]

Foreign wars

Ibn Saud was able to gain loyalty from tribes near Saudi Arabia, tribes such as those in Jordan. For example, he built very strong ties with Prince Sheikh Rashed Al-Khuzai from the Al Fraihat tribe, one of the most influential and royally established families during the Ottoman Empire. Prince Rashed Al-Khuzai and his tribe had dominated eastern Jordan before the arrival of Sharif Hussein.[17] Ibn Saud supported Prince Rashed Al-Khuzai and his followers in rebellion against the Hussein.[18][19]

Prince Rashed supported Izz ad-Din al-Qassam's Palestinian revolution in 1935 which led him and his followers in rebellion against King Abdullah of Jordan. And later in 1937, when they were forced to leave Jordan, Prince Rashed Al Khuzai, his family, and a group of his followers chose to move to Saudi Arabia, where Prince Al Khuzai was living for several years in the hospitality of King Abdul-Aziz Al Saud.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24]

He positioned Saudi Arabia as neutral in World War II, but was generally considered to favor the Allies.[25] However, in 1938, when an attack on a main British pipeline in the Kingdom of Iraq was found to be connected to the German Ambassador, Dr. Fritz Grobba, Ibn Saud provided Grobba with refuge.[26] It was reported that he had been disfavoring the British as of 1937.[27]

In 1948, he participated in the Arab-Israeli War. Saudi Arabia's contribution was generally considered token.[25]

Later years

While the members of the royal family wanted heavenly gardens, splendid cars, and concrete palaces, King Abdulaziz wanted a royal railway from the Persian Gulf to Riyadh and then an extension to Jeddah. This was regarded by all of the advisers living in the country as an old man's folly. Eventually, ARAMCO built the railway, at a cost of $70 million, drawn from the King's oil royalties. It was completed in 1951 and was used commercially after the king's death. It enabled Riyadh to grow into a relatively modern city. But when a paved road was built in 1962, the railway lost its traffic.[28]

Personal life

Ibn Saud was fifteen when he was first married. However, his wife died soon thereafter. He remarried at the age of eighteen and his first son Turki was born.[29] The number of his children is unknown. One source indicates that he had 37 sons, another source 45. His number of wives is put at 22.[30]

- Wadhah bint Muhammad bin 'Aqab[15]

- Tarfah bint Abdullah Al AlSheikh

- Khalid (I) (born 1903, died in infancy)

- Faisal (April 1906 – 25 March 1975); reigned 1964–1975

- Saad (I) (1914–1919)

- Anud (born 1917)

- Nura

- Lulua bint Salih Al Dakhil (married 1906)[31]

- Fahd (I) (1906–1919)

- Al Jawhara bint Musaed Al Jiluwi (died 1919)

- Lajah bint Khalid bin Hithlayn

- Sara (1916 – June 2000)

- Bazza I

- Jawhara bint Saad bin Abdul Muhsin al Sudairi

- Saad (II) (1915–1993)

- Musa'id (born 1923)

- Abdul Mohsin (1925–1985)

- Al Bandari (1928–2008)[33]

- Hassa Al Sudairi (1900–1969)

(The sons are known as the "Sudairi Seven")- Fahd (II) (1920 – 1 August 2005); reigned 1982–2005

- Sultan (1928–2011; crown prince 2005–2011)

- Luluwah (ca 1928–2008)[34]

- Abdul Rahman (born 1931)

- Nayef (1933–2012; crown prince 27 October 2011 – 16 June 2012)

- Turki (II) (born 1934)

- Salman (born 1935; crown prince 18 June 2012 – present)

- Ahmed (born 1942)

- Jawaher

- Latifa

- Al Jawhara

- Moudhi (died young)

- Felwa (died young)

- Shahida

- Fahda bint Asi Al Shuraim

- Bazza (the second wife named Bazza)

- Haya bint Sa'ad Al Sudairi (1913 – 18 April 2003)[37]

- Badr (I) (1931–1932)

- Badr (II) (1933– 1 April 2013)

- Huzza (1951 – July 2000)

- Abdul Ilah (born 1935)

- Abdul Majeed (1943–2007)

- Nura (born 1930)

- Mishail

- Bushra

- Mishari (1931–2000)[36]

- Munaiyir (died December 1991)[36]

- Mudhi Al Sudairi

- Nouf bint al-Shalan

- Saida al Yamaniyah

- Hazloul (1942-29 September 2012)

- Khadra

- Baraka al Yamaniyah

- Muqrin (born 15 September 1945)

- Futayma

- Hamoud (1947 – February 1994)[36]

- By Unknown

- Shaikha (born 1922)

- Majid (I) (1934–1940)

- Abdul Saleem (1941–1942)

- Jiluwi (I) (1942–1944)

- Jiluwi (II) (1952–1952) (the youngest son of Ibn Saud but died as an infant).

Relations with family members

Abdulaziz was said to be very close to his aunt, Al Jowhara bint Faysal. She was a key motivator for him and persuaded him to return to the Najd from Kuwait and regain the land of his family. She was well educated in Islam and was among the king's most trusted advisors. Abdulaziz asked her about the experiences of past rulers and the historical allegiance and role of tribes and individuals. Al Jowhara was also deeply respected by the king's children. Abdulaziz used to visit her daily until she died around 1930.[40]

Abdulaziz was also very close to Nuora, his one-year elder sister. On several occasions, he identified himself in public by proclaiming: “I am the brother of Nuora.”[7][40] Nuora died a few years before King Abdulaziz.[7]

Assassination attempt

On 15 March 1935, armed men attacked and tried to assassinate King Abdulaziz during his performance of Hajj.[41] He survived the attack unhurt.[41]

Views

In regard to essential values for the state and people he said that 'Two things are essential to our State and our people ... religion and the rights inherited from our fathers.'[42]

Amani Hamdan argues that the attitude of Ibn Saud towards women's education was encouraging, since he expressed his support in a conversation with St John Philby, where he stated “It is permissible for women to read.”[43]

His last words to his two sons, the future King Saud and the next in line Prince Faisal, who were already battling each other, were: 'You are brothers, unite!'[15]

Briefly before his death, King Abdulaziz stated "Verily, my children and my possessions are my enemies."[44]

Death and funeral

In October 1953, King Abdulaziz was seriously ill due to heart disease.[45] He died in his sleep of a heart attack at the palace of Prince Faisal in Taif on 9 November 1953 (2 Rabīʿ al-Awwal 1373 AH) at the age of 76.[5][46][47] Prince Faisal was at his side.[47] Funeral prayer was performed at Al Hawiya in Taif.[5] His body was brought to Riyadh where he was buried in Al Oud cemetery.[5][48]

Reactions

The US secretary of state John Foster Dulles stated after the death of King Abdulaziz that he would be remembered for his achievements as a statesman.[49]

References

- ^ His birthday has been a source of debate. It is generally accepted as 1876, although a few sources give it as 1880. According to British author Robert Lacey's book The Kingdom, a leading Saudi historian found records that show Abdul-Aziz in 1891 greeting an important tribal delegation. The historian reasoned that a nine or ten-year-old child (as given by the 1880 birth date) would have been too young to be allowed to greet such a delegation, while an adolescent of 14 or 15 (as given by the 1876 date) would likely have been allowed. When Lacey interviewed one of Abdul-Aziz's sons[which?] prior to writing the book, the son recalled that his father often laughed at records showing his birth date to be 1880. King Abdulaziz's response to such records was reportedly that "I swallowed four years of my life."[page needed]

- ^ Current Biography 1943, pp. 330–34

- ^ Ibn Saud, meaning son of Saud (see Arabic name), was a sort of title borne by previous heads of the House of Saud, similar to a Scottish clan chief's title of "the MacGregor" or "the MacDougall". When used without comment it refers solely to Abdul-Aziz, although prior to the capture of Riyadh in 1902 it referred to his father, Abdul Rahman (Lacey 1982, pp. 15, 65). Al Saud has a similar meaning (family of Saud) and may be used at the end of the full name, while Ibn Saud should sometimes be used alone.[citation needed]

- ^ "King Abdul Aziz family tree". Geocities.ws.

- ^ a b c d "The kings of the Kingdom". Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ Abir, Mordechai (April 1987). "The Consolidation of the Ruling Class and the New Elites in Saudi Arabia". Middle Eastern Studies. 23 (2): 150–171. JSTOR 4283169.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c "King Abdulaziz' Noble Character" (PDF). Islam House. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Stegner, Wallace (2007). "Discovery! The Search for Arabian Oil" (PDF). Selwa Press. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Ochsenwald, William (2004). The Middle East: A History. McGraw Hill. p. 697. ISBN 0-07-244233-6.

- ^ Wilson, Robert, and Zahra Freeth. The Arab of the Desert. London: Allen & Unwin, 1983. 312–13. Print.

- ^ Wilkinson, John C. Arabia's Frontiers: the Story of Britain's Boundary Drawing in the Desert. London [u.a.: Tauris, 1993. 133–39. Print

- ^ Sindi, Abdullah Mohammad. "The Direct Instruments of Western Control over the Arabs: The Shining Example of the House of Saud" (PDF). Social Sciences. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Leatherdale, Clive (1983). Britain and Saudi Arabia, 1925–1939: The Imperial Oasis. New York: Frank Cass and Company.

- ^ Odah, Odah Sultan (1988). "Saudi-American Relations 1968–78: A study in ambiguity" (PDF). Salford University. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Yamani, Mai (2009). "From fragility to stability: a survival strategy for the Saudi monarchy" (PDF). Contemporary Arab Affairs,. 2 (1): 90–105. doi:10.1080/17550910802576114. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Cordesman, Anthony H. (30 October 2002). "Saudi Arabia enters the 21st century: III. Politics and internal stability" (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ http://www.almoarekhsaudi.com/?p=76#

- ^ a b http://www.almoarekhsaudi.com/?p=174

- ^ a b المجلة المصرية نون. "المجلة المصرية نون – سيرة حياة الأمير المناضل راشد الخزاعي". Noonptm.com. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "موقع الثورة الإخباري". Althawra1965.com. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Historical document issued on 28 March 1938 which proved the political asylum of Prince Rashed Al-Khuzai and followers in 1937 to King Abdul-Aziz Al Saud and shows the start of Ajloun revolution

- ^ "الشيخ عز الدين القسام أمير المجاهدين الفلسطينيين – (ANN)". Anntv.tv. 19 November 1935. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "جريدة الرأي | راشد الخزاعي.. من رجالات الوطن ومناضلي الأمة". Alrai.com. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "مركز الشرق العربي ـ برق الشرق". Asharqalarabi.org.uk. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ a b A Country Study: Saudi Arabia. Library of Congress Call Number DS204 .S3115 1993. Chapter 5. World War II and Its Aftermath

- ^ Time Magazine, 26 May 1941

- ^ Time Magazine, 3 July 1939

- ^ Nehme, Michel G. (1994). "Saudi Arabia 1950–80: Between Nationalism and Religion". Middle Eastern Studies. 30 (4): 930–943. JSTOR 4283682.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Reich, Bernard (1990). Political Leaders of the Contemporary Middle East and North Africa. Westport: Greenwood Press.

- ^ Henderson, Simon (25 October 2006). "New Saudi Rules on Succession:". The Washington Institute. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ "Lulua bint Salih al Dakhil". Datarabia. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ^ "Princes of Riyadh". Ministry of Interior. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ "Saudi Princess Al Bandari passes away". Independent Bangladesh. UNB. 11 March 2008. Retrieved April 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Princess Luluwah bint Abdulaziz passed away". Retrieved 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Princess Qumash passes away". Arab News. 27 September 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sabri, Sharaf (2001). The House of Saud in commerce: A study of royal entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. New Delhi: I.S. Publications. ISBN 81-901254-0-0.

- ^ "Saudi princess dies at age 90". Beaver County Times. 4 May 2003. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "Death of Princess Sultanah". Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ http://www.spa.gov.sa/English/details.php?id=715354. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Stenslie, Stig (2011). "Power behind the Veil: Princesses of House of Saud". Journal of Arabian Studies: Arabia, the Gulf, and the Red Sea. 1 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1080/21534764.2011.576050.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Tokumasu, Amin K. "Cultural Relations Between Saudi Arabia and Japan From the Time of King 'Abdulaziz to the Time of King Fahd". Darah. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Nevo, Joseph (1998). "Religion and National Identity in Saudi Arabia". Middle Eastern Studies,. 34 (3): 34–53. JSTOR 4283951.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Hamdan, Amani (2005). "Women and education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and achievements" (PDF). International Education Journal,. 6 (1): 42–64. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Hertog, Steffen (2007). "Shaping the Saudi state: Human agency's shifting role in the rentier state formation". International Journal Middle East Studies. 39: 539–563. doi:10.1017/S0020743807071073.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Warrior King Ibn Saud Dies at 73". The West Australian. 10 November 1953. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ Cavendish, Richard (2003). "Death of Ibn Saud". History Today. 53 (11). Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Ibn Saud dies". King Abdulaziz Information Source. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Shaheen, Abdul Nabi (23 October 2011). "Sultan will have simple burial at Al Oud cemetery". Gulf News. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "Western tributes to King Ibn Saud". The Canberra Times. London. 11 November 1953. p. 5. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

External links

For further reading

- Michael Oren, "Power, Faith and Fantasy: The United States in the Middle East, 1776 to the Present" (Norton, 2007).

- [1] The Egyptian Magazine "Noon", Cairo- Egypt – History of Prince Rashed Al-Khuzai with King Abdul Aziz Al Saud, an article that was published by the American Writer Mr. Muneer Husainy & the Saudi Historian Mr. Khalid Al-Sudairy.This article was published at 27 November 2009.

- [2] Arab News Network, London – United Kingdom – The political relationship between Prince Rashed Al-Khuzai, Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, and Saudi Arabia.

- [3] The Arab Orient Center for Strategic and civilization studies London, United Kingdom- The political relationship between Prince Rashed Al-Khuzai and Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam.

- DeGaury, Gerald.

- DeNovo, John A. American Interests and Policies in the Middle East 1900–1939 University of Minnesota Press, 1963.

- Eddy, William A. FDR Meets Ibn Saud. New York: American Friends of the Middle East, Inc., 1954.

- Iqbal, Dr. Sheikh Mohammad. Emergence of Saudi Arabia (A Political Study of Malik Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud 1901–1953). Srinagar, Kashmir: Saudiyah Publishers, 1977.

- Lacey, Robert (1982). The Kingdom. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-147260-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Long, David. Saudi Arabia Sage Publications, 1976.

- Miller, Aaron David. Search for Security: Saudi Arabian Oil and American Foreign Policy, 1939–1949. University of North Carolina Press, 1980.

- Alsabah – Formal Egyption magazine, Rashed Al Khuzai article .. published in Cairo on 29 March 1938.

- Nicosia, Francis R. (1985). The Third Reich and the Palestine Question. London: I. B. Taurus & Co. Ltd. p. 190. ISBN 1-85043-010-1.

- James Parry, A Man for our Century, Saudi Aramco World, January/February 1999, p4–11

- Philby, H. St. J. B. Saudi Arabia 1955.

- Rentz, George. "Wahhabism and Saudi Arabia". in Derek Hopwood, ed., The Arabian Peninsula: Society and Politics 1972.

- Rihani, Ameen. Ibn Sa'oud of Arabia. Boston: Houghton–Mifflin Company, 1928.

- Sanger, Richard H. The Arabian Peninsula Cornell University Press, 1954.

- Benjamin Shwadran, The Middle East, Oil and the Great Powers, 3rd ed. (1973)

- Troeller, Gary. The Birth of Saudi Arabia:Britain and the Rise of the House of Sa'ud. London: Frank Cass, 1976.

- Twitchell, Karl S. Saudi Arabia Princeton University Press, 1958.

- Van der D. Meulen; The Wells of Ibn Saud. London: John Murray, 1957.

- Weston, Mark, "Prophets and Princes – Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the Present", Wiley, 2008

Directories

- SAMIRAD website – Saudi Arabia Market Information and Directory directory category