Buryat language

| Buryat | |

|---|---|

| Buriat | |

| буряад хэлэн buryaad khelen ᠪᠤᠷᠢᠶᠠᠳ ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠬᠡᠯᠡᠨ | |

| Pronunciation | [bʊˈrʲaːt xɤ̞.ˈlɤ̞ŋ] |

| Native to | Eastern Russia (Buryatia Republic, Ust-Orda Buryatia, Agin Buryatia), northern Mongolia, Northeast China (Hulunbuir, Inner Mongolia) |

| Ethnicity | Buryats, Barga Mongols |

Native speakers | 440,000 (2017–2020)[1] |

| Cyrillic, Mongolian, Vagindra, Latin | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Buryatia (Russia) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | bua Buriat |

| ISO 639-3 | bua – inclusive code BuriatIndividual codes: bxu – Inner Mongolian (China) Buriatbxm – Mongolia Buriatbxr – Russia Buriat |

| Glottolog | buri1258 |

| ELP | |

| |

Buryat is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Buryat or Buriat,[1][2][note 1] known in foreign sources as the Bargu-Buryat dialect of Mongolian, and in pre-1956 Soviet sources as Buryat-Mongolian,[note 2][4] is a variety of the Mongolic languages spoken by the Buryats and Bargas that is classified either as a language or major dialect group of Mongolian.

Geographic distribution

[edit]The majority of Buryat speakers live in Russia along the northern border of Mongolia. In Russia, it is an official language in the Republic of Buryatia and was an official language in the former Ust-Orda Buryatia and Aga Buryatia autonomous okrugs.[5] In the Russian census of 2002, 353,113 people out of an ethnic population of 445,175 reported speaking Buryat (72.3%). Some other 15,694 can also speak Buryat, mostly ethnic Russians.[6] Buryats in Russia have a separate literary standard, written in a Cyrillic alphabet.[7] It is based on the Russian alphabet with three additional letters: Ү/ү, Ө/ө and Һ/һ.

There are at least 100,000 ethnic Buryats in Mongolia and Inner Mongolia, China, as well.[8]

Dialects

[edit]The delimitation of Buryat mostly concerns its relationship to its immediate neighbors, Mongolian proper and Khamnigan. While Khamnigan is sometimes regarded as a dialect of Buryat, this is not supported by isoglosses. The same holds for Tsongol and Sartul dialects, which rather group with Khalkha Mongolian to which they historically belong. Buryat dialects are:

- Khori group east of Lake Baikal comprising Khori, Aga, Tugnui, and North Selenga dialects. Khori is also spoken by most Buryats in Mongolia and a few speakers in Hulunbuir.

- Lower Uda (Nizhneudinsk) dialect, the dialect situated furthest to the west and which shows the strongest influence from Turkic

- Alar–Tunka group comprising Alar, Tunka–Oka, Zakamna, and Unga in the southwest of Lake Baikal. Tunka extends into Mongolia.

- Ekhirit–Bulagat group in the Ust’-Orda National District comprising Ekhirit–Bulagat, Bokhan, Ol’khon, Barguzin, and Baikal–Kudara

- Bargut group in Hulunbuir (which is historically known as Barga), comprising Old Bargut and New Bargut[9]

Based on loan vocabulary, a division might be drawn between Russia Buryat, Mongolia Buryat and Inner Mongolian Buryat.[10] However, as the influence of Russian is much stronger in the dialects traditionally spoken west of Lake Baikal, a division might rather be drawn between the Khori and Bargut group on the one hand and the other three groups on the other hand.[11]

Phonology

[edit]Buryat has the vowel phonemes /i, ʉ, e, a, u, o, ɔ/ (plus a few diphthongs),[12] and the consonant phonemes /b, g, d, tʰ, m, n, x, l, r/ (each with a corresponding palatalized phoneme) and /s, ʃ, z, ʒ, h, j/.[13][14] These vowels are restricted in their occurrence according to vowel harmony.[15] The basic syllable structure is (C)V(C) in careful articulation, but word-final CC clusters may occur in more rapid speech if short vowels of non-initial syllables get dropped.[16]

Vowels

[edit]| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː ‹и ии› |

ʉ ʉː ‹ү үү› |

u uː ‹у уу› | |

| Mid | eː ‹ээ› |

(ə) | ɤ ‹э› | oː ‹өө› |

| ɔ ɔː ‹о оо› | ||||

| Open | a aː ‹а аа› |

|||

Other lengthened vowel sounds that are written as diphthongs, namely ай (aj), ой (oj), and үй (yj), are heard as [ɛː œː yː]. Also, эй (ej) is also rendered homophonous with ээ (ee). In unstressed syllables, /a/ and /ɔ/ become [ɐ], while unstressed /ɤ/ becomes [ə]. These tend to disappear in fast speech.[17]

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | pal. | plain | pal. | plain | pal. | ||||

| Plosive | aspirated | tʰ | tʰʲ | ||||||

| voiced | b | bʲ | d | dʲ | ɡ | ɡʲ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | s | ʃ | x | xʲ | h | |||

| voiced | z | ʒ | |||||||

| Nasal | m | mʲ | n | nʲ | (ŋ)[a] | ||||

| Lateral | l | lʲ | |||||||

| Rhotic | r | rʲ | |||||||

| Approximant | w | j | |||||||

Voiced plosives are half-voiced syllable finally on the first syllable (xob [xɔb̥] 'calumny', xobto [xɔb̥tʰɐ] 'chest'), but completely devoiced on the second syllable onwards (tyleb [tʰʉləp] 'shape', harapša [harɐpʃɐ] 'shed').[18] Velar stops are "postvelarized" in words containing back vowel harmony: gar [ɢar̥] 'hand', xog [xɔɢ̥] 'trash', but not as in ger [gɤr̥] 'house', teeg [tʰeːg̊] 'cross-beam'. Also, /g/ becomes [ʁ] between back vowels (jaagaab [jaːʁaːp] 'what has happened?').[19] The phoneme /n/ becomes [ŋ] before velar consonants, while word finally it may cause nasalization of the preceding vowel (anxan [aŋxɐŋ ~ aŋxɐ̃] 'beginning') In the Aga dialect, /s/ and /z/ are pronounced as non-sibilants [θ] and [ð], respectively. /tʃ/ in loans was often substituted by simple /ʃ/.[20] /r/ is devoiced to [r̥] before voiceless consonants.[21]

Stress

[edit]Lexical stress (word accent) falls on the last heavy nonfinal syllable when one exists. Otherwise, it falls on the word-final heavy syllable when one exists. If there are no heavy syllables, then the initial syllable is stressed. Heavy syllables without primary stress receive secondary stress:[22]

Stress pattern IPA Gloss ˌHˈHL [ˌøːɡˈʃøːxe] "to act encouragingly" LˌHˈHL [naˌmaːˈtuːlxa] "to cause to be covered with leaves" ˌHLˌHˈHL [ˌbuːzaˌnuːˈdiːje] "steamed dumplings (accusative)" ˌHˈHLLL [ˌtaːˈruːlaɡdaxa] "to be adapted to" ˈHˌH [ˈboːˌsoː] "bet" LˈHˌH [daˈlaiˌɡaːr] "by sea" LˈHLˌH [xuˈdaːliŋɡˌdaː] "to the husband's parents" LˌHˈHˌH [daˌlaiˈɡaːˌraː] "by one's own sea" ˌHLˈHˌH [ˌxyːxenˈɡeːˌreː] "by one's own girl" LˈH [xaˈdaːr] "through the mountain" ˈLL [ˈxada] "mountain"[23]

Secondary stress may also occur on word-initial light syllables without primary stress, but further research is required. The stress pattern is the same as in Khalkha Mongolian.[22]

Writing systems

[edit]This section may be very hard to understand. (September 2023) |

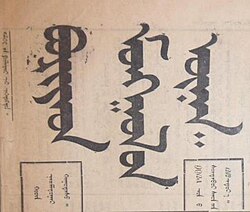

Buryat has been a literary language since the 18th century. Buryats have changed the literary base of their written language three times in order to approach the living spoken language, first using the Mongolian script, switching to Latin in 1930, and finally Cyrillic in 1939, which is currently used.

Mongolian

[edit]From the end of the 17th century, Classical Mongolian was used in clerical and religious practice. The language of the end of the 17th—19th centuries is conventionally referred to as the Old Buryat literary and written language.[citation needed]

Before the October Revolution, clerical records of the Western Buryats were made in the Russian language, and not by the Buryats themselves, but by representatives of the tsarist administration, the so-called clerks. The old Mongolian script was used only by ancestral nobility, lamas and traders Relations with Tuva, Outer and Inner Mongolia.[24]

In 1905, on the basis of the Old Mongolian script, Agvan Dorzhiev developed a script known as Vagindra, which by 1910 had at least a dozen books printed. However, use of vagindra was not widespread.

Latin

[edit]

In 1926, an organized scientific development of the Buryat Latinized writing began in the USSR. In 1929, the draft Buryat alphabet was created. It contained the following letters: A a, B b, C c, Ç ç, D d, E e, Ә ә, Ɔ ɔ, G g, I i, J j, K k, L l, M m, N n, O o, P p, R r, S s, Ş ş, T t, U u, Y y, Z z, Ƶ ƶ, H h, F f, V v.[25] However, this project was not approved. In February 1930, a new version of the Latinized alphabet was approved. It contained letters of the standard Latin alphabet (except for h, q, x), digraphs ch, sh, zh, and also the letter ө. But in January 1931, its modified version was officially adopted, unified with other alphabets of peoples within the USSR.

- Buryat Latin alphabet (1931–39)

| A a | B b | C c | Ç ç | D d | E e | F f | G g |

| H h | I i | J j | K k | L l | M m | N n | O o |

| Ө ө | P p | R r | S s | Ş ş | T t | U u | V v |

| X x[26] | Y y | Z z | Ƶ ƶ | ь[26] |

Cyrillic

[edit]In 1939, the Latinized alphabet was replaced by Cyrillic with the addition of three special letters (Ү ү, Ө ө, Һ һ).

- Modern Buryat Cyrillic alphabet since 1939

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж |

| З з | И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о |

| Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ү ү | Ф ф |

| Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы |

| Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Finally, in 1936, the Khorinsky oriental dialect, close and accessible to most native speakers, was chosen as the basis of the literary language at the linguistic conference in Ulan-Ude.

Buryat alphabet table

[edit]| Cyrillic (с. 1939) |

Latin (1930–1939) |

Latin (1910) |

Mongolian

(pre-1910) |

|---|---|---|---|

| А а | A a | A a | ᠠ |

| Б б | B b | B b | ᠪ |

| В в | V v | - | ᠸ |

| Г г | G g | G g | ᠭ |

| Д д | D d | D d | ᠳ |

| Е е | - | - | - |

| Ё ё | - | - | - |

| Ж ж | Ƶ ƶ | J j | ᠵ |

| З з | Z z | Z z | - |

| И и | I i | I i | ᠢ |

| Й й | J j | Y y | ᠶ |

| К к | K k | - | ᠺ |

| Л л | L l | L l | ᠯ |

| М м | M m | M m | ᠮ |

| Н н | N n | N n | ᠨ, ᠩ |

| О о | O o | O o | ᠣ |

| Ө ө | Ө ө | Eo eo | ᠥ |

| П п | P p | P p | ᠫ |

| Р р | R r | R r | ᠷ |

| С с | S s | C c | ᠰ |

| Т т | T t | T t | ᠲ |

| У у | U u | U u | ᠣ |

| Ү ү | Y y | Eu eu | ᠥ |

| Ф ф | F f | - | - |

| Х х | H h, K k | H h | ᠬ |

| Һ һ | X x | X x | ᠾ |

| Ц ц | C c | C c | - |

| Ч ч | Ç ç | - | ᠴ |

| Ш ш | Ş ş | S s | ᠱ |

| Щ щ | - | - | - |

| Ъ ъ | - | - | - |

| Ы ы | Ь ь | - | - |

| Ь ь | - | - | - |

| Э э | E e | E e | ᠡ |

| Ю ю | - | - | - |

| Я я | - | - | - |

Grammar

[edit]Buryat is an SOV language that makes exclusive use of postpositions. Buryat is equipped with eight grammatical cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, instrumental, ablative, comitative, dative-locative and a particular oblique form of the stem.[28]

Numerals

[edit]| English | Classical Mongolian |

Khalkha | Buryat | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin | Cyrillic | ||||

| 1 | one | nige | neg | negen | нэгэн |

| 2 | two | qoyar | khoyor | khoyor | хоёр |

| 3 | three | hurba(n) | gurav | gurban | гурбан |

| 4 | four | dörbe(n) | döröv | dürben | дүрбэн |

| 5 | five | tabu | tav | taban | табан |

| 6 | six | jirguga(n) | zurgaa | zurgaan | зургаан |

| 7 | seven | doluga(n) | doloo | doloon | долоон |

| 8 | eight | naima(n) | naim | naiman | найман |

| 9 | nine | yisü | yos | yühen | юһэн |

| 10 | ten | arba(n) | arav | arban | арбан |

Buryat language reforms in the Soviet Union

[edit]In September 1931, a joint plenum of the Central Committee and the Central Control Commission of the CPSU (B) was held, which, in line with the decisions of the Central Committee, formulated a course for the construction of a socialist in content and national in form culture of the Buryat people. In the activities of the Institute of Culture, they saw a distortion of the party line in the development of the main issues of national and cultural construction and gave basic guidelines for the Institute's further work. In particular, it was noted that the Old Mongolian writing system penetrated Buryatia from Mongolia along with Lamaism and, before the revolution, "served in the hands of the Lama, Noyonat, and kulaks as an instrument of oppression of illiterate workers." The theory of creating a pan-Mongolian language was recognized as pan-Mongolian and counterrevolutionary. The Institute of Culture was tasked with compiling a new literary language based on the East Buryat (primarily Selenga) dialect. In the early 1930s, the internationalization of the Buryat language and the active introduction of Russian-language revolutionary Marxist terms into it began.[29]

During the next reform in 1936, there was a reorientation to the Khorin dialect. The reform coincided with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, so it was intended to isolate the Buryats from the rest of the Mongol world. In 1939, the Buryat language was translated into the Cyrillic alphabet,[30] a process that coincided with active repression of the Buryat intelligentsia, including scholars and statesmen who had been involved in the language reform. Among them were publicist and literary critic Dampilon, one of the leaders of the Buryat-Mongolian Writers' Union Solbone Tuya, editor of the Buryaad-Mongolian Unen newspaper B. Vancikov and others. They were accused of "polluting the Buryat language with Pan-Mongolian and Lama-religious terms," as well as of counter-revolutionary, Pan-Mongolian distortions of the works of the classics of Marxism-Leninism, and of Mongolizing their native language, namely, "translating into Mongolian with the selection of reactionary Buddhist feudal-theocratic, Khan Wan words that are incomprehensible and inaccessible to the population of Soviet Buryatia."[31][32]

Since 1938, Russian was introduced as a compulsory language from the 1st grade, thus consolidating Buryat-Russian bilingualism. Changes in the spelling, alphabet and literary norms on which the language is based reduced the prestige of the Buryat language, consolidating Russian domination in the region. In the 1940s, the Soviet Union completely stopped printing in the Old Mongolian language. The so-called "Pan-Mongolian" words, which were actually Mongolian and Tibetan, were massively replaced by "international" words, i.e. Russian.[33][34]

Artificial Russification

[edit]The Buryats are the indigenous people of the Republic of Buryatia, yet today the majority of the republic's residents are of Russian nationality. According to the 1989 All-Union Population Census, the region was home to about 1,038,000 people, including 726,200 Russians (70%) and 249,500 Buryats (24%). Twenty years later, according to the 2010 All-Russian Census, 461,400 Buryats lived in Russia. The permanent population of Buryatia amounted to about 972,000 people, including 630,780 (66.1%) Russians and 286,840 (30%) Buryats.[35][36]

Since the days of the Russian Empire, the Russian authorities have made efforts to destroy the national and cultural identity of the Buryats. For example, in today's Russia, the territories inhabited by ethnic Buryats are divided between the Republic of Buryatia and the Ust-Ordyn Buryat District in the Irkutsk Oblast, as well as the Aginsky Buryat District in the Trans-Baikal Territory. In addition to these administrative-territorial units, Buryats live in some other neighboring districts of the Irkutsk Oblast and Trans-Baikal Territory.[37][38]

One of the reasons for the artificial division of Buryats into different administrative units was the fight against so-called "pan-Mongolism" and "Buryat nationalism" that began in the 1920s. In an effort to break the cultural, linguistic, and historical ties of the Buryat-Mongols with Mongolia, the Soviet and later Russian authorities pursued a decisive policy of Russification, the settlement of the Republic of Buryatia by Russians, the replacement of the Mongolian script with the Cyrillic alphabet, and so on. At the moment, UNESCO has officially included the Buryat language in the Red Book of Endangered Languages. According to the 2010 All-Russian Census, 130,500 people in the Republic of Buryatia spoke Buryat, or only 13.4% of the total population. Currently, the process of reducing the spheres of use of the Buryat language continues. Russian is compulsory in Buryat schools, while Buryat is optional. There is a lack of Buryat-language publications, TV channels, periodicals, etc.[39][40]

Notes

[edit]- ^ /ˈbʊriæt/;[3] Buryat Cyrillic: буряад хэлэн, buryaad khelen, pronounced [bʊˈrʲaːt xɤ̞.ˈlɤ̞ŋ]

- ^ In China, the Buryat language is classified as the Bargu-Buryat dialect of the Mongolian language.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Buryat at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Inner Mongolian (China) Buriat at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Mongolia Buriat at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Russia Buriat at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forke, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2020). "Buriat". Glottolog 4.3.

- ^ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- ^ Тодаева Б. Х. Монгольские языки и диалекты Китая. Moscow, 1960.

- ^ Skribnik 2003: 102, 105

- ^ Russian Census (2002)

- ^ Skribnik 2003: 105

- ^ Skribnik 2003: 102

- ^ Skribnik 2003: 104

- ^ Gordon (ed.) 2005

- ^ Skribnik 2003: 102, 104

- ^ Poppe 1960, p. 8

- ^ Svantesson et al. (2005:146)

- ^ Svantesson et al. (2005:146); the status of [ŋ] is problematic, see Skribnik (2003:107). In Poppe 1960's description, places of vowel articulation are somewhat more fronted.

- ^ Skribnik (2003:107)

- ^ Poppe 1960, p. 13-14

- ^ Poppe 1960, p. 8–9

- ^ Poppe 1960, p. 9

- ^ Poppe 1960, p. 11

- ^ Poppe 1960, p. 12

- ^ Poppe 1960, p. 13

- ^ a b Walker (1997)[page needed]

- ^ Walker (1997:27–28)

- ^ Окладников А. П. Очерки из истории западных бурят-монголов.

- ^ Барадин Б. (1929). Вопросы повышения бурят-монгольской языковой культуры. Баку: Изд-во ЦК НТА. p. 33.

- ^ a b Letter established in 1937

- ^ "Buryat romanization" (PDF). Institute of the Estonian Language. 2012-09-26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-27. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ^ "Overview of the Buriat Language". Learn the Buriat Language & Culture. Transparent Language. Retrieved 4 Nov 2011.

- ^ "Языковая ситуация в Республике Бурятия". (in Russian)

- ^ "Interesting Facts About the Buryat Language".

- ^ ""В Кремле не хотят, чтобы мы осознали свое единство"". 23 April 2018. (in Russian)

- ^ "Живая речь в Бурятии: к проблеме изучения (социолингвистический обзор)". (in Russian)

- ^ ""Языковое строительство" в бурят-монгольской АССР в 1920-1930-е годы". (in Russian)

- ^ "Chronology for Buryat in Russia".

- ^ "Information about the Buryat Language". Язык И Культура Современных Бурят.

- ^ "Этническая идентичность и языковое сознание носителей бурятского языка: социо- и психолингвистические исследования". (in Russian)

- ^ Chakars, Melissa (2020). "The All-Buryat Congress for the Spiritual Rebirth and Consolidation of the Nation: Siberian politics in the final year of the USSR". Journal of Eurasian Studies. 11: 62–71. doi:10.1177/1879366520902863.

- ^ ""В Кремле не хотят, чтобы мы осознали свое единство"". 23 April 2018. (in Russian)

- ^ "Языковая ситуация в Республике Бурятия". (in Russian)

- ^ "Бурятский язык в глобальной языковой системе". (in Russian)

Sources

[edit]- Poppe, Nicholas (1960). Buriat grammar. Uralic and Altaic series. Vol. 2. Bloomington: Indiana University.

- Skribnik, Elena (2003). "Buryat". In Juha Janhunen (ed.). The Mongolic languages. London: Routledge. pp. 102–128.

- Svantesson, Jan-Olof; Tsendina, Anna; Karlsson, Anastasia; Franzén, Vivan (2005). The Phonology of Mongolian. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Walker, Rachel (1997), Mongolian stress, licensing, and factorial typology

- Санжеев Г. Д. (1962). Грамматика бурятского языка. Фонетика и морфология [Sanzheev, G.D. Grammar of Buryat. Phonetics and morphology] (PDF, 23 Mb) (in Russian).

- (ru) Н. Н. Поппе, Бурят-монгольское языкознание, Л., Изд-во АН СССР, 1933

- Anthology of Buryat folklore, Pushkinskiĭ dom, 2000 (CD)