Agaricus

| Agaricus | |

|---|---|

| |

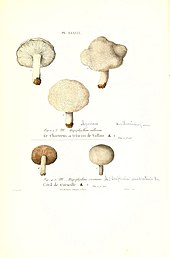

| The type species Agaricus campestris (field or meadow mushroom) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Agaricaceae |

| Genus: | Agaricus L. (1753) |

| Type species | |

| Agaricus campestris L. (1753)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

Agaricus is a genus of mushroom-forming fungi containing both edible and poisonous species, with over 400 members worldwide[2][3] and possibly again as many disputed or newly-discovered species. The genus includes the common ("button") mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) and the field mushroom (A. campestris), the dominant cultivated mushrooms of the West.

Description

[edit]Members of Agaricus are characterized by having a fleshy cap or pileus, from the underside of which grow a number of radiating plates or gills, on which are produced the naked spores. They are distinguished from other members of their family, Agaricaceae, by their chocolate-brown spores. Members of Agaricus also have a stem or stipe, which elevates it above the object on which the mushroom grows, or substrate, and a partial veil, which protects the developing gills and later forms a ring or annulus on the stalk.

Taxonomy

[edit]

Several origins of genus name Agaricus have been proposed. It possibly originates from ancient Sarmatia Europaea, where people Agari, promontory Agarum and a river Agarus were known (all located on the northern shore of Sea of Azov, probably, near modern Berdiansk in Ukraine).[4][5][6]

Note also Greek ἀγαρικόν, agarikón, "a sort of tree fungus" (There has been an Agaricon Adans. genus, treated by Donk in Persoonia 1:180.)

For many years, members of the genus Agaricus were given the generic name Psalliota, and this can still be seen in older books on mushrooms. All proposals to conserve Agaricus against Psalliota or vice versa have so far been considered superfluous.[7]

Dok reports Linnaeus' name is devalidated (so the proper author citation apparently is "L. per Fr., 1821") because Agaricus was not linked to Tournefort's name. Linnaeus places both Agaricus Dill. and Amanita Dill. in synonymy, but truly a replacement for Amanita Dill., which would require A. quercinus, not A. campestris be the type. This question is compounded because Fries himself used Agaricus roughly in Linnaeus' sense (which leads to issues with Amanita), and A. campestris was eventually excluded from Agaricus by Karsten and was apparently in Lepiota at the time Donk wrote this, commenting that a type conservation might become necessary.[8]

The alternate name for the genus, Psalliota, derived from the Greek psalion/ψάλιον, "ring", was first published by Fries (1821) as trib. Psalliota. The type is Agaricus campestris (widely accepted, except by Earle, who proposed A. cretaceus). Paul Kummer (not Quélet, who merely excluded Stropharia) was the first to elevate the tribe to a genus. Psalliota was the tribe containing the type of Agaricus, so when separated, it should have caused the rest of the genus to be renamed, but this is not what happened.[9]

Phylogeny

[edit]The use of phylogenetic analysis to determine evolutionary relationships amongst Agaricus species has increased the understanding of this taxonomically difficult genus, although much work remains to be done to fully delineate infrageneric relationships. Prior to these analyses, the genus Agaricus, as circumscribed by Rolf Singer, was divided into 42 species grouped into five sections based on reactions of mushroom tissue to air or various chemical reagents, as well as subtle differences in mushroom morphology.[10] Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis demonstrated this classification scheme needed revision.[11]

Subdivisions

[edit]As of 2018, this genus is divided into 6 subgenera and more than 20 sections:[12][13][14]

Subgenus Agaricus

- Section Agaricus

- This is the group around the type species of the genus, the popular edible A. campestris which is common across the Holarctic temperate zone, and has been introduced to some other regions. One of the more ancient lineages of the genus, it contains species typically found in open grassland such as A. cupreobrunneus, and it also includes at least one undescribed species. Their cap surface is whitish to pale reddish-brown and smooth to slightly fibrous, the flesh usually without characteristic smell, fairly soft, whitish, and remaining so after injury, application of KOH, or Schäffer's test (aniline and HNO3). A. annae may also belong here, as might A. porphyrocephalus, but the flesh of the latter blushes red when bruised or cut, and it has an unpleasant smell of rotten fish when old; these traits are generally associated with subgenus Pseudochitonia, in particular section Chitonioides. The A. bresadolanus/radicatus/romagnesii group which may be one or several species is sometimes placed here, but may be quite distinct and belong to subgenus Spissicaules.

Subgenus Flavoagaricus

- Traditionally contained about 20 rather large species similar to the horse mushroom A. arvensis in six subgroups. Today, several additional species are recognized – in particular in the A. arvensis species complex – and placed here, such as A. aestivalis, A. augustus, A. caroli, A. chionodermus, A. deserticola (formerly Longula texensis), A. fissuratus, A. inapertus (formerly Endoptychum depressum), A. macrocarpus, A. nivescens, A. osecanus, A. silvicola and the doubtfully distinct A. essettei, A. urinascens, and the disputed taxa A. abruptibulbus, A. albertii, A. altipes, A. albolutescens, A. brunneolus, A. excellens and A. macrosporus. It also includes A. subrufescens which started to be widely grown and traded under various obsolete and newly-invented names in the early 21st century, as well as the Floridan A. blazei with which the Brazilian A. subrufescens was often confused in the past. They have versatile heterothallic life cycles,[15] are found in a variety of often rather arid habitats, and typically have a smooth white to scaly light brown cap. The flesh, when bruised, usually turns distinctly yellow to pinkish in particular on the cap, while the end of the stalk may remain white; a marked yellow stain is caused by applying KOH. Their sweetish smell of almond extract or marzipan due to benzaldehyde and derived compounds distinguishes them from the section Xanthodermatei, as does a bright dark-orange to brownish-red coloration in Schäffer's test. Many members of this subgenus are highly regarded as food, and even medically beneficial, but at least some are known to accumulate cadmium and other highly toxic chemicals from the environment, and may not always be safe to eat.

Subgenus Minores

- A group of buff-white to reddish-brown species. Often delicate and slender, the typical members of this subgenus do not resemble the larger Agaricus species at a casual glance, but have the same telltale chocolate-brown gills at spore maturity. Their flesh has a barely noticeable to pronounced sweetish smell, typically almond-like, turns yellowish to brownish-red when cut or bruised at least in the lower stalk, yellow to orange with KOH, and orange to red in Schäffer's test. Species such as A. aridicola (formerly known as Gyrophragmium dunalii), A. colpeteii, A. columellatus (formerly Araneosa columellata), A. diminutivus, A. dulcidulus, A. lamelliperditus, A. luteomaculatus, A. porphyrizon, A. semotus and A. xantholepis are included here, but delimitation to and indeed distinctness from subgenus Flavoagaricus is a long-standing controversy. Unlike these however, subgenus Minores contains no choice edible species, and may even include some slightly poisonous ones; most are simply too small to make collecting them for food worthwhile, and their edibility is unknown.

- Section Leucocarpi

- Includes A. leucocarpus.

- Section Minores

- Includes A. comtulus and A. huijsmanii.

- Unnamed section

- Includes A. candidolutescens and an undescribed relative.

Subgenus Minoriopsis

- Somewhat reminiscent of subgenus Minores and like it closely related to subgenus Flavoagaricus, it contains species such as A. martinicensis and A. rufoaurantiacus.

Subgenus Pseudochitonia

- This highly diverse clade of mid-sized to largish species makes up much the bulk of the genus' extant diversity, and this subgenus contains numerous as of yet undescribed species. It includes both the most prized edible as well as the most notoriously poisonous Agaricus, and some of its sections are in overall appearance more similar to the more distantly related Agaricus proper and Flavoagaricus than to their own closest relatives. Some species in this subgenus, such as A. goossensiae and A. rodmanii, are not yet robustly assigned to one of the sections.

- Section Bohusia

- Includes A. bohusii which resembles one of the dark-capped Flavoagaricus or Xanthodermatei but does not stain yellow with the standard (10%) KOH testing solution. It is a woodland species, edible when young, but when mature and easily distinguished from similar species it may be slightly poisonous. Other members of this section include A. crassisquamosus, A. haematinus, and A. pseudolangei.

- Section Brunneopicti

- A section notable for containing a considerable number of undescribed species in addition to A. bingensis, A. brunneopictus, A. brunneosquamulosus, A. chiangmaiensis, A. duplocingulatus, A. megacystidiatus, A. niveogranulatus, A. sordidocarpus, A. subsaharianus, and A. toluenolens.

- Section Chitonioides

- Contains species such as A. bernardii and the doubtfully distinct A. bernardiiformis, A. gennadii, A. nevoi, A. pequinii, A. pilosporus and A. rollanii, which strongly resemble the members of section Duploannulatae and are as widely distributed. However, their flesh tends to discolor more strongly red when bruised or cut, with the discoloration slowly getting stronger. Their smell is usually also more pronounced umami-like, in some even intensely so. Some are edible and indeed considered especially well-tasting, while the unusual A. maleolens which may also belong here has an overpowering aroma which renders it inedible except perhaps in small amounts as a vegan fish sauce substitute.

- Section Crassispori

- Related to section Xanthodermatei as traditionally circumscribed, it includes such species as A. campestroides, A. lamellidistans, and A. variicystis.

- Section Cymbiformes He, Chuankid, Hyde, Cheewangkoon & Zhao

- A section proposed in 2018, it is closely related to the traditional section Xanthodermatei. The type species A. angusticystidiatus from Thailand is a smallish beige Agaricus with characteristic boat-shaped basidiospores. It has a strong unpleasant smell like members of section Xanthodermatei, but unlike these, its flesh does not change color when bruised, but turns dark reddish-brown when cut, and neither application of KOH nor Schäffer's test elicit a change in color.[14]

- Section Duploannulatae (also known as section Bivelares or Hortenses)

- Traditionally often included in section Agaricus as subsection Bitorques, it seems to belong to a much younger radiation. It unites robust species, usually with a thick, almost fleshy ring, which inhabit diverse but often nutrient-rich locations. Some are well-known edibles; as they are frequently found along roads and in similar polluted places, they may not be safe to eat if collected from the wild. Their flesh is rather firm, white, with no characteristic smell, in some species turning markedly reddish when bruised or cut (though this may soon fade again), and generally changing color barely if at all after application of KOH or Schäffer's test. Based on DNA analysis of ITS1, ITS2, and 5.8S sequences, the studied species of this section could be divided into six distinct clades, four of which correspond to well-known species from the temperate Northern Hemisphere: A. bisporus, A. bitorquis (and the doubtfully distinct A. edulis), A. cupressicola and A. vaporarius. The other two clades comprise the A. devoniensis (including A. subperonatus) and A. subfloccosus (including A. agrinferus) species complexes.[16] Additional members of this section not included in that study are A. cappellianus, A. cupressophilus, A. subsubensis, A. taeniatus, A. tlaxcalensis, and at least one undescribed species.[17] The cultivated mushrooms traded as A. sinodeliciosus also belong here, though their relationship to the A. devoniensis complex and A. vaporarius is unclear.

- Section Flocculenti

- Includes A. erectosquamosus and A. pallidobrunneus; a more distant undescribed relative of these two may also belong in this section.

- Section Hondenses (disputed)

- Traditionally included in section Xanthodermatei sensu lato, this clade may be included therein as the most basal branch, or considered a section in its own right. It includes such species as A. biannulatus, A. freirei and its North American relatives A. grandiomyces, A. hondensis, and probably also A. phaeolepidotus. They are very similar to section Xanthodermatei sensu stricto in all aspects, except for a weaker discoloration tending towards reddish rather than chrome yellow when bruised.

- Section Nigrobrunnescentes

- Includes A. biberi, A. caballeroi, A. desjardinii, A. erthyrosarx, A. fuscovelatus, A. nigrobrunnescens, A. padanus, A. pattersoniae, and probably also A. boisselettii.

- Section Rubricosi

- Includes A. dolichopus, A. kunmingensis, A. magnivelaris, A. variabilicolor, and at least two undescribed species.

- Section Sanguinolenti

- Usually found in woodland. Brownish cap with a fibrous surface, typically felt-like but sometimes scaly. The fairly soft flesh turns pink, blood-red or orange when cut or scraped, in particular the outer layer of the stalk, but does not change color after application of KOH or Schäffer's test. Some North American species traditionally placed here, such as A. amicosus and A. brunneofibrillosus, do not seem to be closely related to the section's type species A. silvaticus (including A. haemorrhoidarius which is sometimes considered a distinct species), and represent at least a distinct subsection. Other species often placed in this section are A. benesii, A. dilutibrunneus, A. impudicus, A. koelerionensis, A. langei and A. variegans; not all of these may actually belong here. They are generally (though not invariably) regarded as edible and tasty.

- Section Trisulphurati (disputed)

- Includes the A. trisulphuratus species complex which is often placed in genus Cystoagaricus, but seems to be a true Agaricus closely related to the traditional section Xanthodermatei. Their stalk is typically bright yellow-orange, quite unlike that of other Agaricus, as is the scaly cap. A.trisulphuratus was the type species of the obsolete polyphyletic subgenus Lanagaricus, whose former species are now placed in various other sections.

- Section Xanthodermatei

- As outlined by Singer in 1948, this section includes species with various characteristics similar to the type species A. xanthodermus.[18] The section forms a single clade based on analysis of ITS1+2.[19] They are either bright white all over, or have a cap densely flecked with brownish scales or tufts of fibers. The ring is usually large but thin and veil-like. Most inhabit woodland, and in general they have a more or less pronounced unpleasant smell of phenolic compounds such as hydroquinone. As food, they should all be avoided, because even though they are occasionally reported to be eaten without ill effect, the chemicals they contain give them a acrid, metallic taste, especially when cooked, and are liable to cause severe gastrointestinal upset. Their flesh at least in the lower stalk turns pale yellow to intensely reddish-ochre when bruised or cut; more characteristic however is the a bright yellow reaction with KOH while Schäffer's test is negative. Apart from A. xanthodermus, the core group of this section contains species such as A. atrodiscus, A. californicus, A. endoxanthus and the doubtfully distinct A. rotalis, A. fuscopunctatus, A. iodosmus, A. laskibarii, A. microvolvatulus, A. menieri, A. moelleri, A. murinocephalus, A. parvitigrinus, A. placomyces, A. pocillator, A. pseudopratensis, A. tibetensis, A. tollocanensis, A. tytthocarpus, A. xanthodermulus, A. xanthosarcus, as well as at least 4 undescribed species, and possibly A. cervinifolius and the doubtfully distinct A. infidus. Whether such species as A. bisporiticus, A. nigrogracilis and A. pilatianus are more closely related to the mostly Eurasian core group, or to the more basal lineage here separated as section Hondenses, requires clarification.

Subgenus Spissicaules

- The flesh of members of this subgenus tends to turn more or less pronouncedly yellowish in the lower stalk, where the skin is often rough and scaly, and reddish in the cap. They typically resemble the darker members of subgenus Flavoagaricus, with a sweet smell and mild taste; like that subgenus, Spissicaules belongs to the smaller of the two main groups of the genus, but they form entirely different branch therein. While some species are held to be edible, others are considered unappetizing or even slightly poisonous. Also includes A. lanipes and A. maskae, which probably belong to section Rarolentes or Spissicaules, and possibly also A. bresadolanus and its doubtfully distinct relatives A. radicatus/romagnesii.

- Section Amoeni

- Includes A. amoenus and A. gratolens.

- Section Rarolentes

- Includes A. albosquamosus and A. leucolepidotus.

- Section Spissicaules (Hainem.) Kerrigan

- Includes species such as A. leucotrichus/litoralis (of which A. spissicaulis is a synonym, but see also Geml et al. 2004[13]) and A. litoraloides. Most significantly, some species have a persistent and unpleasant rotting-wood smell entirely unlike the sweet aroma of Flavoagaricus, and while not known to be poisonous, are certainly unpalatable.

- Section Subrutilescentes

- Includes A. brunneopilatus, A. linzhinensis and A. subrutilescens. Somewhat similar to section Sanguinolenti or the dark-capped species of section Xanthodermatei, but the flesh does not show a pronounced red or yellow color change when cut or bruised. Edibility is disputed.

Selected species

[edit]The fungal genus Agaricus as late as 2008 was believed to contain about 200 species worldwide[20] but since then, molecular phylogenetic studies have revalidated several disputed species, as well as resolved some species complexes, and aided in discovery and description of a wide range of mostly tropical species that were formerly unknown to science. As of 2020, the genus is believed to contain no fewer than 400 species, and possibly many more.

The medicinal mushroom known in Japan as Echigoshirayukidake (越後白雪茸) was initially also thought to be an Agaricus, either a subspecies of Agaricus "blazei"[21] (i.e. A. subrufescens), or a new species.[22] It was eventually identified as sclerotium of the crust-forming bark fungus Ceraceomyces tessulatus, which is not particularly closely related to Agaricus.

Several secotioid (puffball-like) fungi have in recent times be recognized as highly aberrant members of 'Agaricus, and are now included here. These typically inhabit deserts where few fungi – and even fewer of the familiar cap-and-stalk mushroom shape – grow. Another desert species, A. zelleri, was erroneously placed in the present genus and is now known as Gyrophragmium californicum. In addition, the scientific names Agaricus and – even more so – Psalliota were historically often used as a "wastebasket taxon" for any and all similar mushrooms, regardless of their actual relationships.

Species either confirmed or suspected to belong into this genus include:

- Agaricus abramsii

Agaricus abruptibulbus – abruptly-bulbous agaricus, flat-bulb mushroom (disputed)

Agaricus abruptibulbus – abruptly-bulbous agaricus, flat-bulb mushroom (disputed) Agaricus aestivalis

Agaricus aestivalis- Agaricus agrinferus (disputed)

- Agaricus agrocyboides

- Agaricus alabamensis

- Agaricus alachuanus

- Agaricus albidoperonatus

- Agaricus albertii Bon (1988) (disputed)

- Agaricus alboargillascens

- Agaricus alboides

Agaricus albolutescens (disputed)

Agaricus albolutescens (disputed)- Agaricus albosanguineus

- Agaricus albosquamosus

- Agaricus alligator

Agaricus altipes Møller (often united with A.aestivalis)[23]

Agaricus altipes Møller (often united with A.aestivalis)[23]- Agaricus amanitiformis

Agaricus amicosus

Agaricus amicosus- Agaricus amoenomyces

- Agaricus amoenus

Agaricus andrewii Freeman[23]

Agaricus andrewii Freeman[23]- Agaricus angelicus

- Agaricus angusticystidiatus

- Agaricus anisarius

- Agaricus annae

- Agaricus annulospecialis

- Agaricus approximans

- Agaricus arcticus

- Agaricus argenteopurpureus

- Agaricus argenteus

- Agaricus argentinus[24]

- Agaricus argyropotamicus

- Agaricus argyrotectus

- Agaricus aridicola Geml, Geiser & Royse (2004) (formerly in Gyrophragmium)[13]

- Agaricus aristocratus

- Agaricus arizonicus

- Agaricus armandomyces

- Agaricus arorae

- Agaricus arrillagarum

Agaricus arvensis – horse mushroom

Agaricus arvensis – horse mushroom- Agaricus atrodiscus

Agaricus augustus – the prince

Agaricus augustus – the prince Agaricus aurantioviolaceus

Agaricus aurantioviolaceus- Agaricus auresiccescens

- Agaricus australiensis

- Agaricus austrovinaceus

- Agaricus azoetes

- Agaricus babosiae

- Agaricus badioniveus

- Agaricus bajan-agtensis

- Agaricus balchaschensis

- Agaricus bambusae

- Agaricus bambusophilus

- Agaricus basianulosus

- Agaricus beelii

- Agaricus bellanniae

- Agaricus benesii

- Agaricus benzodorus

Agaricus bernardii – salt-loving mushroom

Agaricus bernardii – salt-loving mushroom- Agaricus bernardiiformis (disputed)

- Agaricus berryessae

- Agaricus biannulatus Mua, L.A.Parra, Cappelli & Callac (2012) (Europe)[25]

- Agaricus biberi

- Agaricus bicortinatellus

- Agaricus bilamellatus

- Agaricus bingensis

- Agaricus bisporatus

- Agaricus bisporiticus (Asia)[26]

Agaricus bisporus – cultivated/button/portobello mushroom (includes A.brunnescens)

Agaricus bisporus – cultivated/button/portobello mushroom (includes A.brunnescens) Agaricus bitorquis – pavement mushroom, banded agaric

Agaricus bitorquis – pavement mushroom, banded agaric- Agaricus bivelatoides

- Agaricus bivelatus

- Agaricus blatteus

- Agaricus blazei Murrill (often confused with A. subrufescens)

- Agaricus blockii

- Agaricus bobosi

- Agaricus bohusianus L.A.Parra (2005) (Europe)[27]

- Agaricus bohusii

- Agaricus boisselettii

- Agaricus boltonii

- Agaricus bonii

- Agaricus bonussquamulosus

- Agaricus brasiliensis Fr. (often confused with A. subrufescens)

- Agaricus bresadolanus

- Agaricus bruchii

Agaricus brunneofibrillosus (formerly in A.fuscofibrillosus)

Agaricus brunneofibrillosus (formerly in A.fuscofibrillosus)- Agaricus brunneofulva

- Agaricus brunneofulvus

- Agaricus brunneolus (disputed)

- Agaricus brunneopictus

- Agaricus brunneopilatus

- Agaricus brunneosquamulosus

- Agaricus brunneostictus

- Agaricus buckmacadooi

- Agaricus bugandensis

- Agaricus bukavuensis

- Agaricus bulbillosus

- Agaricus burkillii

- Agaricus butyreburneus

- Agaricus caballeroi L.A.Parra, G.Muñoz & Callac (2014) (Spain)[28]

- Agaricus caesifolius

Agaricus californicus – California agaricus

Agaricus californicus – California agaricus- Agaricus callacii

- Agaricus calongei

- Agaricus campbellensis[29]

Agaricus campestris – field/meadow mushroom

Agaricus campestris – field/meadow mushroom- Agaricus campestroides

- Agaricus campigenus

- Agaricus candidolutescens

- Agaricus candussoi

- Agaricus capensis

- Agaricus cappellianus

- Agaricus cappellii

- Agaricus caribaeus

- Agaricus carminescens

- Agaricus carminostictus

- Agaricus caroli

- Agaricus catenariocystidiosus

- Agaricus catenatus

- Agaricus cellaris

- Agaricus cervinifolius

- Agaricus cerinupileus

- Agaricus chacoensis

- Agaricus chartaceus[30]

- Agaricus cheilotulus

- Agaricus chiangmaiensis

- Agaricus chionodermus[31]

- Agaricus chlamydopus

- Agaricus chryseus

- Agaricus cinnamomellus

- Agaricus circumtectus

- Agaricus ciscoensis

- Agaricus citrinidiscus

- Agaricus coccyginus

- Agaricus collegarum

- Agaricus colpeteii[32]

- Agaricus columellatus (formerly in Araneosa)

- Agaricus comptuloides

- Agaricus comtulellus

- Agaricus comtuliformis[33]

- Agaricus comtulus

- Agaricus coniferarum

- Agaricus cordillerensis

- Agaricus crassisquamosus

- Agaricus cretacellus

- Agaricus cretaceus

- Agaricus croceolutescens

- Agaricus crocodilinus

- Agaricus crocopeplus

- Agaricus cruciquercorum

- Agaricus cuniculicola

Agaricus cupreobrunneus – brown field mushroom

Agaricus cupreobrunneus – brown field mushroom- Agaricus cupressicola

- Agaricus cupressophilus Kerrigan (2008) (California)[17]

- Agaricus curanilahuensis

- Agaricus cylindriceps

- Agaricus deardorffensis

- Agaricus dennisii

- Agaricus depauperatus

- Agaricus deplanatus

Agaricus deserticola G.Moreno, Esqueda & Lizárraga (2010) – gasteroid agaricus (formerly in Longula)

Agaricus deserticola G.Moreno, Esqueda & Lizárraga (2010) – gasteroid agaricus (formerly in Longula)- Agaricus desjardinii

- Agaricus devoniensis

- Agaricus diamantanus

- Agaricus dicystis

- Agaricus didymus

- Agaricus dilatostipes

- Agaricus dilutibrunneus

- Agaricus diminutivus

- Agaricus dimorphosquamatus

- Agaricus diobensis

- Agaricus diospyros

- Agaricus dolichopus

- Agaricus ducheminii

Agaricus dulcidulus – rosy wood mushroom (sometimes in A.semotus)

Agaricus dulcidulus – rosy wood mushroom (sometimes in A.semotus)- Agaricus duplocingulatus

- Agaricus ealaensis

- Agaricus earlei

- Agaricus eastlandensis

- Agaricus eburneocanus[30]

- Agaricus edmondoi

- Agaricus elfinensis

- Agaricus elongatestipes

- Agaricus eludens

- Agaricus endoxanthus[34]

- Agaricus entibigae

- Agaricus erectosquamosus

- Agaricus erindalensis

- Agaricus erthyrosarx[30]

- Agaricus erythrotrichus

- Agaricus essettei (disputed)

- Agaricus eutheloides

- Agaricus evertens

Agaricus excellens (disputed)

Agaricus excellens (disputed)- Agaricus exilissimus

- Agaricus eximius

- Agaricus fiardii

- Agaricus fibuloides

- Agaricus ficophilus

- Agaricus fimbrimarginatus

- Agaricus fissuratus

- Agaricus flammicolor

- Agaricus flavicentrus

- Agaricus flavidodiscus

- Agaricus flavistipus

- Agaricus flavitingens

- Agaricus flavopileatus

- Agaricus flavotingens

- Agaricus flocculosipes

- Agaricus floridanus

- Agaricus fontanae

- Agaricus fragilivolvatus

- Agaricus freirei

- Agaricus friesianus

- Agaricus fulvoaurantiacus

- Agaricus fuscofolius

- Agaricus fuscopunctatus (Thailand)[26]

- Agaricus fuscovelatus[35]

- Agaricus gastronevadensis

- Agaricus gemellatus

- Agaricus gemlii

- Agaricus gemloides

- Agaricus gennadii

- Agaricus gilvus

- Agaricus glaber

- Agaricus glabrus

- Agaricus globocystidiatus

- Agaricus globosporus

- Agaricus goossensiae

- Agaricus grandiomyces

- Agaricus granularis

- Agaricus gratolens

- Agaricus greigensis

- Agaricus greuteri

- Agaricus griseicephalus

- Agaricus griseopunctatus

- Agaricus griseorimosus

- Agaricus griseovinaceus

- Agaricus guachari

- Agaricus guidottii

- Agaricus haematinus

- Agaricus haematosarcus

- Agaricus hahashimensis

- Agaricus halophilus

- Agaricus hannonii

- Agaricus hanthanaensis

- Agaricus heimii

- Agaricus heinemannianus

- Agaricus heinemanniensis

- Agaricus heinemannii

- Agaricus herinkii

- Agaricus herradurensis

- Agaricus heterocystis

- Agaricus hillii

- Agaricus hispidissimus

Agaricus hondensis – felt-ringed agaricus

Agaricus hondensis – felt-ringed agaricus- Agaricus horakianus

- Agaricus horakii

- Agaricus hornei

- Agaricus hortensis

- Agaricus huijsmanii Courtec. (2008)

- Agaricus hupohanae

- Agaricus hypophaeus

- Agaricus iesu-et-marthae

- Agaricus ignicolor

- Agaricus ignobilis

Agaricus impudicus – tufted wood mushroom

Agaricus impudicus – tufted wood mushroom- Agaricus inapertus (formerly in Endoptychum)

- Agaricus incultorum

- Agaricus indistinctus

- Agaricus inedulis

- Agaricus infelix

- Agaricus infidus (disputed)

- Agaricus inilleasper[30]

- Agaricus inoxydabilis

- Agaricus inthanonensis

- Agaricus iocephalopsis

- Agaricus iodolens

- Agaricus iodosmus

- Agaricus iranicus

- Agaricus jacarandae

- Agaricus jacobi

- Agaricus jezoensis

- Agaricus jingningensis

- Agaricus jodoformicus

- Agaricus johnstonii

- Agaricus julius

- Agaricus junquitensis

- Agaricus kai

- Agaricus kauffmanii

- Agaricus kerriganii

- Agaricus kiawetes

- Agaricus kipukae

- Agaricus kivuensis

- Agaricus koelerionensis

- Agaricus kriegeri

- Agaricus kroneanus

- Agaricus kuehnerianus

- Agaricus kunmingensis

- Agaricus lacrymabunda

- Agaricus laeticulus

- Agaricus lamellidistans

- Agaricus lamelliperditus[32]

- Agaricus lanatoniger

- Agaricus lanatorubescens

- Agaricus langei (= A.fuscofibrillosus)

- Agaricus lanipedisimilis

- Agaricus lanipes – European princess

- Agaricus laparrae

- Agaricus laskibarii[36]

- Agaricus lateriticolor

- Agaricus leptocaulis

- Agaricus leptomeleagris

- Agaricus leucocarpus

- Agaricus leucolepidotus

Agaricus leucotrichus Møller[37] (disputed)

Agaricus leucotrichus Møller[37] (disputed)- Agaricus lignophilus

Agaricus lilaceps – giant cypress agaricus

Agaricus lilaceps – giant cypress agaricus- Agaricus linzhinensis

- Agaricus litoralis – coastal mushroom (includes A.spissicaulis)

- Agaricus litoraloides

- Agaricus lividonitidus

- Agaricus lodgeae

- Agaricus lotenensis

- Agaricus lucifugus[verification needed]

- Agaricus ludovicii[38]

- Agaricus lusitanicus

- Agaricus luteofibrillosus

- Agaricus luteoflocculosus

- Agaricus luteomaculatus

- Agaricus luteopallidus

- Agaricus luteotactus

- Agaricus lutosus

- Agaricus luzonensis

- Agaricus maclovianus[39]

- Agaricus macmurphyi

- Agaricus macrocarpus

- Agaricus macrolepis (Pilát & Pouzar) Boisselet & Courtec. (2008)

Agaricus macrosporus (disputed)

Agaricus macrosporus (disputed)- Agaricus macrosporoides

- Agaricus magni

- Agaricus magniceps

- Agaricus magnivelaris

- Agaricus maiusculus

- Agaricus malangelus

- Agaricus maleolens

- Agaricus mangaoensis

- Agaricus manilensis

- Agaricus marisae

- Agaricus martineziensis

- Agaricus martinicensis

- Agaricus maskae

- Agaricus masoalensis

- Agaricus matrum

- Agaricus medio-fuscus

- Agaricus megacystidiatus

- Agaricus megalosporus

- Agaricus meijeri

- Agaricus melanosporus

Agaricus menieri

Agaricus menieri- Agaricus merrillii

- Agaricus mesocarpus

- Agaricus microchlamidus

Agaricus micromegathus[verification needed][40]

Agaricus micromegathus[verification needed][40]- Agaricus microspermus

- Agaricus microviolaceus

- Agaricus microvolvatulus

- Agaricus midnapurensis[41]

- Agaricus minimus

- Agaricus minorpurpureus

Agaricus moelleri – inky/dark-scaled mushroom (formerly in A.placomyces, includes A.meleagris)

Agaricus moelleri – inky/dark-scaled mushroom (formerly in A.placomyces, includes A.meleagris)- Agaricus moellerianus

- Agaricus moelleroides

- Agaricus moronii

- Agaricus multipunctum

- Agaricus murinocephalus (Thailand)[42]

- Agaricus nanaugustus Kerrigan

- Agaricus nebularum

- Agaricus neimengguensis

- Agaricus nemoricola

- Agaricus nevoi

- Agaricus nigrescentibus

- Agaricus nigrobrunnescens

- Agaricus nigrogracilis

- Agaricus nitidipes

- Agaricus niveogranulatus

- Agaricus niveolutescens

- Agaricus nivescens

- Agaricus nobelianus

- Agaricus nothofagorum

- Agaricus novoguineensis

- Agaricus ochraceidiscus

- Agaricus ochraceosquamulosus

- Agaricus ochrascens

- Agaricus oenotrichus

- Agaricus oligocystis

- Agaricus olivellus

- Agaricus ornatipes

- Agaricus osecanus

- Agaricus pachydermus[30]

- Agaricus padanus

- Agaricus pallens

- Agaricus pallidobrunneus

- Agaricus pampeanus

- Agaricus panziensis

- Agaricus parasilvaticus

- Agaricus parasubrutilescens

- Agaricus parvibicolor

- Agaricus parvitigrinus[43]

- Agaricus patialensis

- Agaricus patris

Agaricus pattersoniae

Agaricus pattersoniae- Agaricus pearsonii

- Agaricus peligerinus

- Agaricus pequinii

- Agaricus perdicinus

- Agaricus perfuscus

Agaricus perobscurus – American princess

Agaricus perobscurus – American princess- Agaricus perrarus

- Agaricus perturbans

- Agaricus petchii

- Agaricus phaeocyclus

Agaricus phaeolepidotus

Agaricus phaeolepidotus- Agaricus phaeoxanthus

- Agaricus pietatis

Agaricus pilatianus

Agaricus pilatianus- Agaricus pilosporus

Agaricus placomyces (includes A.praeclaresquamosus)

Agaricus placomyces (includes A.praeclaresquamosus)- Agaricus planipileus

- Agaricus pleurocystidiatus

Agaricus pocillator

Agaricus pocillator- Agaricus porosporus

- Agaricus porphyrizon

Agaricus porphyrocephalus Møller[44]

Agaricus porphyrocephalus Møller[44]- Agaricus porphyropos

- Agaricus posadensis

- Agaricus praefoliatus

- Agaricus praemagniceps

- Agaricus praemagnus

- Agaricus praerimosus

- Agaricus pratensis

- Agaricus pratulorum

- Agaricus projectellus

- Agaricus proserpens

- Agaricus pseudoargentinus

- Agaricus pseudoaugustus

- Agaricus pseudocomptulus

- Agaricus pseudolangei

- Agaricus pseudolutosus

- Agaricus pseudomuralis

- Agaricus pseudoniger

- Agaricus pseudopallens

- Agaricus pseudoplacomyces

- Agaricus pseudopratensis

- Agaricus pseudopurpurellus

- Agaricus pseudoumbrella

- Agaricus pulcherrimus

- Agaricus pulverotectus

- Agaricus punjabensis

- Agaricus purpurellus

- Agaricus purpureofibrillosus

- Agaricus purpureoniger

- Agaricus purpureosquamulosus[41]

- Agaricus purpurlesquameus

- Agaricus putidus

- Agaricus puttemansii

- Agaricus radicatus (disputed)

- Agaricus reducibulbus

- Agaricus rhoadsii

- Agaricus rhopalopodius

- Agaricus riberaltensis

- Agaricus robustulus

- Agaricus robynsianus

- Agaricus rodmanii

- Agaricus rollanii

- Agaricus romagnesii (disputed)

- Agaricus rosalamellatus[45]

- Agaricus roseocingulatus

- Agaricus rotalis (disputed)

- Agaricus rubellus

- Agaricus rubronanus Kerrigan (1985)[35] (San Mateo county)

- Agaricus rubribrunnescens

- Agaricus rufoaurantiacus

- Agaricus rufolanosus

- Agaricus rufotegulis

- Agaricus rufuspileus

- Agaricus rusiophyllus

- Agaricus rutilescens

- Agaricus salicophilus

- Agaricus sandianus

Agaricus santacatalinensis

Agaricus santacatalinensis- Agaricus sceptonymus

- Agaricus scitulus

- Agaricus semotellus

Agaricus semotus

Agaricus semotus- Agaricus sequoiae[35] (Mendocino County, CA, under coast redwood)

- Agaricus shaferi

Agaricus silvaticus – scaly/blushing wood mushroom, pinewood mushroom (= A.sylvaticus, includes A.haemorrhoidarius)

Agaricus silvaticus – scaly/blushing wood mushroom, pinewood mushroom (= A.sylvaticus, includes A.haemorrhoidarius) Agaricus silvicola – wood mushroom (= A.sylvicola)

Agaricus silvicola – wood mushroom (= A.sylvicola)- Agaricus silvicolae-similis

- Agaricus silvipluvialis

- Agaricus simillimus

- Agaricus singaporensis

- Agaricus singeri

- Agaricus sinodeliciosus

- Agaricus sipapuensis

- Agaricus slovenicus

- Agaricus smithii [35]

- Agaricus sodalis

Agaricus solidipes Peck, Bull (1904)[46]

Agaricus solidipes Peck, Bull (1904)[46]- Agaricus sordido-ochraceus

- Agaricus sordidocarpus

- Agaricus spegazzinianus

- Agaricus stadii

- Agaricus stellatus-cuticus

- Agaricus sterilomarginatus

- Agaricus sterlingii

- Agaricus stevensii

- Agaricus stigmaticus Courtec. (2008)

- Agaricus stijvei

- Agaricus stramineus

- Agaricus subalachuanus

- Agaricus subantarcticus[29]

- Agaricus subareolatus

- Agaricus subarvensis

- Agaricus subcoeruleus

- Agaricus subcomtulus

- Agaricus subedulis

- Agaricus subflabellatus

- Agaricus subfloccosus

- Agaricus subfloridanus

- Agaricus subgibbosus

- Agaricus subhortensis

- Agaricus subnitens

- Agaricus subochraceosquamulosus

- Agaricus suboreades

- Agaricus subperonatus (disputed)

- Agaricus subplacomyces-badius

- Agaricus subponderosus

- Agaricus subpratensis

Agaricus subrufescens (includes A.rufotegulis, often confused with A.blazei and A.brasiliensis) – almond mushroom, royal sun agaricus, and various fanciful names

Agaricus subrufescens (includes A.rufotegulis, often confused with A.blazei and A.brasiliensis) – almond mushroom, royal sun agaricus, and various fanciful names- Agaricus subrufescentoides

Agaricus subrutilescens – wine-colored agaricus

Agaricus subrutilescens – wine-colored agaricus- Agaricus subsaharianus L.A.Parra, Hama & De Kesel (2010)

- Agaricus subsilvicola

- Agaricus subsquamuliferus

- Agaricus subsubensis Kerrigan (2008) (California)[17]

- Agaricus subtilipes

- Agaricus subvariabilis

- Agaricus sulcatellus

- Agaricus sulphureiceps

- Agaricus summensis Kerrigan (1985)[35]

- Agaricus suthepensis

- Agaricus taculensis

- Agaricus taeniatimpictus

- Agaricus taeniatus

- Agaricus tantulus

- Agaricus tennesseensis

- Agaricus tenuivolvatus

- Agaricus tephrolepidus

- Agaricus termiticola

- Agaricus termitum

- Agaricus thiersii

- Agaricus thujae

- Agaricus tibetensis

- Agaricus tlaxcalensis Callac & G.Mata (2008) (Tlaxcala)[17]

- Agaricus tollocanensis

- Agaricus toluenolens

- Agaricus trinitatensis

- Agaricus trisulphuratus (formerly in Cystoagaricus)

- Agaricus trutinatus

- Agaricus tucumanensis

- Agaricus tytthocarpus

- Agaricus umboninotus

- Agaricus unguentolens

- Agaricus unitinctus

Agaricus urinascens

Agaricus urinascens- Agaricus valdiviae

- Agaricus vaporarius

- Agaricus variabilicolor

- Agaricus variegans

- Agaricus variicystis

- Agaricus valdiviae[47][48]

- Agaricus velenovskyi

- Agaricus veluticeps

- Agaricus venus

- Agaricus vinaceovirens (San Francisco Peninsula)[35]

- Agaricus vinosobrunneofumidus

- Agaricus viridarius

- Agaricus viridopurpurascens

- Agaricus volvatulus

- Agaricus wariatodes

- Agaricus weberianus

- Agaricus wilmotii

- Agaricus woodrowii

- Agaricus wrightii

- Agaricus xanthodermoides

- Agaricus xanthodermulus[43]

Agaricus xanthodermus – yellow-staining mushroom

Agaricus xanthodermus – yellow-staining mushroom- Agaricus xantholepis[49]

- Agaricus xanthosarcus

- Agaricus xeretes

- Agaricus xuchilensis

- Agaricus yunnanensis

- Agaricus zelleri

Toxicity

[edit]

A notable group of poisonous Agaricus is the clade around the yellow-staining mushroom, A. xanthodermus.[50]

One species reported from Africa, A. aurantioviolaceus, is reportedly deadly poisonous.[51]

Far more dangerous is the fact that Agaricus, when still young and most valuable for eating, are easily confused with several deadly species of Amanita (in particular the species collectively called "destroying angels", as well as the white form of the appropriately-named "death cap" Amanita phalloides), as well as some other highly poisonous fungi. An easy way to recognize Amanita is the gills, which remain whitish at all times in that genus. In Agaricus, by contrast, the gills are only initially white, turning dull pink as they mature, and eventually the typical chocolate-brown as the spores are released.

Even so, Agaricus should generally be avoided by inexperienced collectors, since other harmful species are not as easily recognized, and clearly recognizable mature Agaricus are often too soft and maggot-infested for eating. When collecting Agaricus for food, it is important to identify every individual specimen with certainty, since one Amanita fungus of the most poisonous species is sufficient to kill an adult human – even the shed spores of a discarded specimen are suspected to cause life-threatening poisoning. Confusing poisonous Amanita with an edible Agaricus is the most frequent cause of fatal mushroom poisonings world-wide.

Reacting to some distributors marketing dried agaricus or agaricus extract to cancer patients, it has been identified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a "fake cancer 'cure'".[52] The species most often sold as such quack cures is A. subrufescens, which is often referred to by the erroneous name "Agaricus Blazei" and advertised by fanciful trade names such as "God's mushroom" or "mushroom of life", but can cause allergic reactions and even liver damage if consumed in excessive amounts.[53]

Uses

[edit]The genus contains the most widely consumed and best-known mushroom today, A. bisporus, with A. arvensis, A. campestris and A. subrufescens also being well-known and highly regarded. A. porphyrocephalus is a choice edible when young,[44] and many others are edible as well, namely members of sections Agaricus, Arvense, Duploannulatae and Sanguinolenti.[12][54]

References

[edit]- ^ "Synonymy: Agaricus L., Sp. pl. 2: 1171 (1753)". Index Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- ^ Bas C. (1991). A short introduction to the ecology, taxonomy and nomenclature of the genus Agaricus, 21–24. In L.J.L.D. Van Griensven (ed.), Genetics and breeding of Agaricus. Pudoc, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- ^ Capelli A. (1984). Agaricus. L.: Fr. (Psalliota Fr.). Liberia editrice Bella Giovanna, Saronno, Italy

- ^ Rolfe R. T.; Rolfe F. W. (1874). "The derivation of fungus names". The Romance of the Fungus World. Courier Corporation. pp. 292–293. ISBN 9780486231051.

- ^ R. Talbert, ed. (2000). "Map 84. Maeotis". Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press.

- ^ W. Smith, ed. (1854). "Agari". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Vol. I. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. p. 72. (on Google Books, on archive.org)

- ^ Wakesfield E. (1940). "Nomina genérica conservando. Contributions from the Nomenclature Committee of the British Mycological Society, III". Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 24 (3–4): 282–293. doi:10.1016/s0007-1536(40)80028-4.

- ^ Donk, M.A. (1962). "The generic names proposed for Agaricaceae". Beihefte zur Nova Hedwigia. 5: 1–320. ISSN 0078-2238.

- ^ Donk, M.A. (1962). "The generic names proposed for Agaricaceae". Beihefte zur Nova Hedwigia 5: 1–320. ISSN 0078-2238

- ^ Singer, Rolf (1987). Agaricales in Modern Taxonomy. Lubrecht & Cramer Ltd. ISBN 978-3-7682-0143-8.

- ^ Bunyard BA, Nicholson MS, Royse DJ (December 1996). "Phylogeny of the genus Agaricus inferred from restriction analysis of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA". Fungal Genet Biol. 20 (4): 243–53. doi:10.1006/fgbi.1996.0039. PMID 9045755.

- ^ a b Bon, Marcel (1987) The Mushrooms and Toadstools of Britain and North Western Europe. Hodder and Stoughton, ISBN 0 340 39935 X (paperback) ISBN 0 340 39953 8 (hardback)

- ^ a b c Geml J, Geiser DM, Royse DJ (2004). "Molecular evolution of Agaricus species based on ITS and LSU rDNA sequences". Mycological Progress. 3 (2): 157–76. Bibcode:2004MycPr...3..157G. doi:10.1007/s11557-006-0086-8. S2CID 40265528.

- ^ a b He, Mao-Qiang; Chuankid, Boontiya; Hyde, Kevin D.; Cheewangkoon, Ratchadawan; Zhao, Rui-Lin (2018). "A new section and species of Agaricus subgenus Pseudochitonia from Thailand". MycoKeys (40): 53–67. doi:10.3897/mycokeys.40.26918. PMC 6160818. PMID 30271264.

- ^ Calvo-Bado L, Noble R, Challen M, Dobrovin-Pennington A, Elliott T (February 2000). "Sexuality and Genetic Identity in the Agaricus Section Arvenses". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 (2): 728–34. Bibcode:2000ApEnM..66..728C. doi:10.1128/AEM.66.2.728-734.2000. PMC 91888. PMID 10653743.

- ^ Challen MP, Kerrigan RW, Callac P (2003). "A phylogenetic reconstruction and emendation of Agaricus section Duploannulatae". Mycologia. 95 (1): 61–73. doi:10.2307/3761962. JSTOR 3761962. PMID 21156589.

- ^ a b c d Kerrigan RW, Callac P, Parra LA (2008). "New and rare taxa in Agaricus section Bivelares (Duploannulati)". Mycologia. 100 (6): 876–92. doi:10.3852/08-019. PMID 19202842. S2CID 25519596.

- ^ Singer R (1948). "Diagnoses Fungorum Novorum Agaricalium". Sydowia. 2: 26–42.

- ^ Kerrigan RW, Callac P, Guinberteau J, Challen MP, Parra LA (2005). "Agaricus section Xanthodermatei: a phylogenetic reconstruction with commentary on taxa". Mycologia. 97 (6): 1292–315. doi:10.3852/mycologia.97.6.1292. PMID 16722221.

- ^ Kirk PM, Cannon PF, Minter DW, Stalpers JA (2008). Dictionary of the Fungi (10th ed.). Wallingford, UK: CAB International. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-85199-826-8.

- ^ US 6120772A, Hitoshi Ito & Toshimitsu Sumiya, "Oral drugs for treating AIDS patients", issued 2000-09-19

- ^ Watanabe, T; Nakajima, Y; Konishi, T (2008). "In vitro and in vivo anti-oxidant activity of hot water extract of basidiomycetes-X, newly identified edible fungus" (PDF). Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 31 (1): 111–7. doi:10.1248/bpb.31.111. PMID 18175952. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ a b Phillips 2010, p. 219.

- ^ (1899). Spegazzini C. (1899). Fungi argentini novi vel critici. Anales Mus. Nac. Buenos Aires 24: 167–186.

- ^ Parra LA, Mua A, Cappelli A, Callac P (2012). "Agaricus biannulatus sp. nov., una nuova specie della sezione Xanthodermatei raccolta in Sardegna e Sicilia". Micologia e Vegetazione Mediterranea (in Italian). 26 (1): 3–30.

- ^ a b Thongklang N, Nawaz R, Khalid AN, Chen J, Hyde KD, Zhao R, Parra LA, Hanif M, Moinard M, Callac P (2014). "Morphological and molecular characterization of three Agaricus species from tropical Asia (Pakistan, Thailand) reveals a new group in section Xanthodermatei". Mycologia. 106 (6): 1220–32. doi:10.3852/14-076. PMID 25152000. S2CID 2119.

- ^ Parra LA (2005). "Nomenclatural study of the genus Agaricus L. (Agaricales, Basidiomycotina) of the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic Islands". Cuadernos de Trabajo Flora Micológica Ibérica. 21: 3–101.

- ^ Parra LA, Muñoz G, Callac P (2014). "Agaricus caballeroi sp. nov., una nueva especie de la sección Nigrobrunnescentes recolectada en España". Micologia e Vegetazione Mediterranea (in Spanish). 29 (1): 21–38.

- ^ a b Geml J, Laursen GA, Nusbaum HC, Taylor DL (2007). "Two new species of Agaricus from the subantarctic". Mycotaxon. 100: 193–208.

- ^ a b c d e Lebel T, Syme A (2011). "Sequestrate species of Agaricus and Macrolepiota from Australia: new species and combinations, and their position in a calibrated phylogeny". Mycologia. 104 (2): 496–520. doi:10.3852/11-092. PMID 22067305. S2CID 26266778.

- ^ Pilát A. (1951). The Bohemian species of the genus Agaricus. Prague, 142 pp.

- ^ a b Lebel T. (2013). "Two new species of sequestrate Agaricus (section Minores) from Australia". Mycological Progress. 12 (4): 699–707. Bibcode:2013MycPr..12..699L. doi:10.1007/s11557-012-0879-x. S2CID 18497645.

- ^ Murrill WA (1922). "Dark-spored agarics: III. Agaricus". Mycologia. 14 (4): 200–221. doi:10.2307/3753642. JSTOR 3753642.

- ^ Parra LA, Villarreal M, Esteve-Raventos F (2002). "Agaricus endoxanthus una specie tropicale trovata in Spagna". Rivista di Micologia. 45 (3): 225–233.

- ^ a b c d e f Kerrigan R (1985). "Studies in Agaricus III: New Species from California". Mycotaxon. 22: 419–434.

- ^ Parra LA, Arrillaga P (2002). "Agaricus laskibarii. A new species from French coastal sand-dunes of Seignosse". Doc Mycol. 31 (124): 33–38.

- ^ Phillips 2010, p. 223.

- ^ Remy L (1964). "Contribution a l'etude de la Flore mycologique Briangonnaise (Basidiomycetes et Discomycetes)". Bull. Trimestriel Soc. Mycol. France. 80: 459–585.

- ^ Nauta MM (1999). "The Mycoflora of the Falkland Islands: II. Notes on the genus Agaricus". Kew Bulletin. 54 (3): 621–635. Bibcode:1999KewBu..54..621N. doi:10.2307/4110859. JSTOR 4110859.

- ^ Phillips 2010, p. 224.

- ^ a b Tarafder, Entaj; Dutta, Arun Kumar; Acharya, Krishnendu (2022-03-29). "New species and new record in Agaricus subg. Minores from India". Turkish Journal of Botany. 46 (2): 183–195. doi:10.55730/1300-008X.2681. ISSN 1300-008X. S2CID 248936875.

- ^ Zhao R-L, Desjardin DE, Callac P, Parra LA, Guinberteau J, Soytong K, Karunarathna S, Zhang Y, Hyde KD (2012). "Two species of Agaricus sect. Xanthodermatei from Thailand". Mycotaxon. 122: 122–95. doi:10.5248/122.187.

- ^ a b Callac P, Guinberteau J (2005). "Morphological and molecular characterization of two novel species of Agaricus section Xanthodermatei". Mycologia. 97 (2): 416–24. doi:10.3852/mycologia.97.2.416. PMID 16396349.

- ^ a b Phillips 2010, p. 220.

- ^ Raithelhuber J (1986). "Nomina nova". Metrodiana. 14: 22.

- ^ Murrill, William (1922). "Dark-Spored Agarics". Mycologia. 14. New York Botanical Garden: 203.

- ^ Singer R, Moser M (1965). "Forest mycology and forest communities in South America". Mycopathol. Mycol. Appl. 26 (2–3): 129–191. doi:10.1007/BF02049773. S2CID 45170297.

- ^ Heinemann P (1986). "Agarici Austroamericani VI. Aperçu sur les Agaricus de Patagonie et de la Terre de Feu". Bull. Jard. Bot. Belg. 56 (3/4): 417–446. doi:10.2307/3668202. JSTOR 3668202.

- ^ Gerault A. (2005). Florule evolutive des basidiomycotina du Finistere – Homobasidiomycetes – Agaricales: 22.

- ^ Buczacki, Stefan; Shields, Chris; Ovenden, Denys (2012). Collins Fungi Guide: The most complete field guide to the mushrooms and toadstools of Britain & Ireland. HarperCollins UK. p. 49. ISBN 9780007242900.

- ^ Walleyn R; Rammeloo J. (1994). The Poisonous and Useful Fungi of Africa South of the Sahara. Scripta Botanica Belgica. Vol. 10. National Botanic Garden of Belgium. p. 10. ISBN 978-90-72619-22-8.

- ^ "187 Fake Cancer 'Cures' Consumers Should Avoid". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ "Agaricus". Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Phillips 2010, pp. 219, 223.

Sources

[edit]- Phillips, Roger (2010). Mushrooms and Other Fungi of North America. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-651-2.