Hydrodynamica

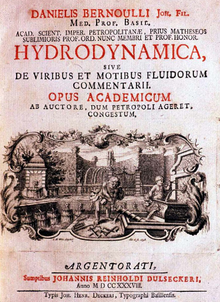

Front page | |

| Author | Daniel Bernoulli |

|---|---|

| Language | Latin |

| Subject | Fluid dynamics |

| Published | 1738 |

| Publisher | Johann Reinhold Dulsecker |

| Publication place | Strasbourg, France |

Hydrodynamica, sive de Viribus et Motibus Fluidorum Commentarii (Latin for Hydrodynamics, or commentaries on the forces and motions of fluids) is a book published by Daniel Bernoulli in 1738.[1] The title of this book eventually christened the field of fluid mechanics as hydrodynamics.

This book introduced the Bernoulli's principle, stating the first form of conservation of energy in fluid dynamics.

Description

[edit]The book deals with fluid mechanics and is organized around preliminary versions of the conservation of energy, as received from Christiaan Huygens's formulation of vis viva (Latin for living forces). The book describes the theory of water flowing through a tube and of water flowing from a hole in a container. In doing so, Bernoulli explained the nature of hydrodynamic pressure and discovered the role of loss of vis viva in fluid flow, which would later be known as the Bernoulli principle. The book also discusses hydraulic machines and introduces the notion of work and efficiency of a machine.

In the tenth chapter, Bernoulli discussed a primitive version of kinetic theory of gases. Assuming that heat increases the velocity of the gas particles, he first demonstrated that the pressure of air is proportional to kinetic energy of gas particles, thus making the temperature of gas proportional to this kinetic energy as well.[1] In this chapter Bernoulli introduces a correction to the volume that appears in Boyle's law, anticipating the Van der Waals equation by more than a century. However most of Bernoulli's theories of this chapter were ignored historically.[2]

Table of contents

[edit]The book is divided in 13 sections:[3]

- Which is the introduction, and contains various matters to be considered initially

- Which discusses the equilibrium of fluids at rest, both within themselves, as well as related to other causes

- Concerning the velocities of fluids flowing from some kind of vessel through an opening of any kind

- Concerned with the various times, which are desired in the efflux of the water

- Concerning the motion of water from vessels being filled constantly

- Concerning fluids not flowing out, or, moving within the walls of the vessels

- Concerning the motion of water through submerged vessels, where it is shown by examples, either how significantly useful the principle of the conservation of living forces shall be, or as in these cases in which a certain amount is agreed to be lost from these continually.

- Concerning the motion both of homogeneous as well as heterogeneous fluids through vessels of irregular construction divided up into several parts, where the individual phenomena of the trajectories of the fluids through a number of openings may be explained and a part of the motion may be absorbed continually from the theory of living forces; and with the general rules for the motions of the fluids defined everywhere

- Concerning the motion of fluids which are not ejected by their own weight but by certain other forces, and which concern hydraulic machines, especially where the highest degree of perfection of the same can be given, and how they can be perfected further both by the mechanics of solids as well as of fluids

- Concerning the properties and motions of elastic fluids, but especially those of air.

- Concerning fluids acting in a vortex, also those which may be contained in moving vessels. This is a relatively short chapter, in which Bernoulli tries to reconcile the vortex theory of planetary motion with Newton’s Law of gravitation, as well as presenting the theory of fluid vortices, and some interesting experiments involving fluids in accelerating frames of reference.

- Which presents the static properties of moving fluids, what I call static-hydraulics

- Concerning the reaction of fluids flowing out of vessels, and with the impulse of the same after they have flowed out, on planes which they meet.

Reception

[edit]Leonhard Euler, friend of Daniel Bernoulli, sent his criticism as soon as the book was published. Bernoulli accepted some of the criticism but considered that Euler's work on fluids was too abstract and did not describe the real world.[4]

A rivalry priority dispute started between Daniel and his father Johann Bernoulli who had also written on the matter.[4] Johann claimed priority on the Bernoulli's principle.[4] Johann's book Hydraulica was published in 1740.[4]

-

A 1738 copy of Hydrodynamica

-

First page of the first section of Hydrodynamica, 1738

References

[edit]- ^ a b Mikhailov 2005, pp. 131–42

- ^ Grattan-Guinness, Ivor (2005-02-11). Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640-1940. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-045744-4.

- ^ Bruce, Ian (2014). "Daniel Bernoulli's Hydrodynamicae". 17centurymaths. Retrieved 2025-03-21.

- ^ a b c d Garber, Elizabeth (2012-12-06). The Language of Physics: The Calculus and the Development of Theoretical Physics in Europe, 1750–1914. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-1766-4.

Bibliography

[edit]- Mikhailov, G.K. (2005). "Hydrodynamica". In Grattan-Guinness, Ivor (ed.). Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640–1940. Elsevier. pp. 131–42. ISBN 978-0-08-045744-4.

- Bernoulli, Daniel (1738). Hydrodynamica, sive de viribus et motibus fluidorum commentarii (in Latin, source ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Rar 5503). sumptibus Johannis Reinholdi Dulseckeri; Typis Joh. Deckeri, typographi Basiliensis. doi:10.3931/e-rara-3911.