Hungarians in Romania

Romániai magyarok | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 1,002,151[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 232,157 (79.51%) | |

| 133,444 (66.71%) | |

| 165,014 (31.84%) | |

| 93,491 (28.27%) | |

| 112,387 (20.39%) | |

| 78,455 (11.55%) | |

| Languages | |

| Primarily Hungarian and Romanian | |

| Religion | |

| Calvinism (45.3%), Roman Catholicism (40.4%), Unitarianism (4.6%) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Hungarian diaspora as well as Hungarians in Serbia and Hungarians in Slovakia | |

The Hungarian minority of Romania (Hungarian: romániai magyarok, pronounced [ˈromaːnijɒji ˈmɒɟɒrok]; Romanian: maghiarii din România) is the largest ethnic minority in Romania. As per the 2021 Romanian census, 1,002,151 people (6% of respondents) declared themselves Hungarian, while 1,038,806 people (6.3% of respondents) stated that Hungarian was their mother tongue.[1]

Most ethnic Hungarians of Romania live in areas that were parts of Hungary before the Treaty of Trianon of 1920. Encompassed in a region known as Transylvania, the most prominent of these areas is known generally as Székely Land (Romanian: Ținutul Secuiesc; Hungarian: Székelyföld), where Hungarians comprise the majority of the population.[2] Transylvania, in the larger sense, also includes the historic regions of Banat, Crișana and Maramureș. There are forty-one counties of Romania; Hungarians form a large majority of the population in the counties of Harghita (85.21%) and Covasna (73.74%), and a large percentage in Mureș (38.09%), Satu Mare (34.65%), Bihor (25.27%), Sălaj (23.35%), and Cluj (15.93%) counties.

There also is a community of Hungarians living mostly in Moldavia, known as the Csángós. These live in the so-called region of Csángó Land in Moldavia but also in parts of Transylvania and in a village of Northern Dobruja known as Oituz. In addition, sparse populations of Székelys are to be found across southern Bukovina, inhabiting several villages and communes in Suceava County. Aside from the aforementioned historical regions of Romania, Bucharest was also home in the past and still is to a sizable Hungarian-Romanian community.

History

[edit]Historical background

[edit]

The Hungarian tribes originated in the vicinity of the Ural Mountains and arrived in the territory formed by present-day Romania during the 9th century from Etelköz or Atelkuzu (roughly the space occupied by the present day Southern Ukraine, the Republic of Moldova and the Romanian province of Moldavia).[3][non-primary source needed] Due to various circumstances (see Honfoglalás), the Magyar tribes crossed the Carpathians around 895 AD and occupied the Carpathian Basin (including present-day Transylvania) without significant resistance from the local populace.[4] The precise date of the conquest of Transylvania is not known; the earliest Magyar artifacts found in the region are dated to the first half of the 10th century.

In 1526, at the Battle of Mohács, the forces of the Ottoman Empire annihilated the Hungarian army and in 1571 Transylvania became an autonomous state, under the Ottoman suzerainty. The Principality of Transylvania was governed by its princes and its parliament (Diet). The Transylvanian Diet consisted of three Estates (Unio Trium Nationum): the Hungarian nobility (largely ethnic Hungarian nobility and clergy); the leaders of Transylvanian Saxons-German burghers; and the free Székely Hungarians.

With the defeat of the Ottomans at the Battle of Vienna in 1683, the Habsburg monarchy gradually began to impose their rule on the formerly autonomous Transylvania. From 1711 onward, after the conclusion of Rákóczi's War for Independence, Habsburg control over Transylvania was consolidated, and the princes of Transylvania were replaced with Habsburg imperial governors.[5] In 1765 the Grand Principality of Transylvania was proclaimed, consolidating the special separate status of Transylvania within the Habsburg Empire, established by the Diploma Leopoldinum in 1691.[6] The Hungarian historiography sees this as a mere formality.[7] Within the Habsburg Empire, Transylvania was administratively part of Kingdom of Hungary.[5]

After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Transylvania became an integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary again, with Hungarian becoming the official language and Magyarization being introduced in the region not soon after.

Following defeat in World War I, Austria-Hungary disintegrated. The ethnic Romanian elected representatives of Transylvania, Banat, Crișana, and Maramureș proclaimed Union with Romania on 1 December 1918. With the conclusion of World War I and the Hungarian–Romanian War (1918–1919), the Treaty of Trianon (signed on 4 June 1920) defined the new border between the states of Hungary and Romania. As a result, the more than 1.5 million Hungarian minority of Transylvania found itself becoming a minority group within Romania.[8] Also after World War I, a group of Csángó families founded a village in Northern Dobruja known as Oituz, where Hungarians still live today.[9]

In August 1940, during the Second World War, the northern half of Transylvania was returned to Hungary by the second Second Vienna Award. Historian Keith Hitchins[10] summarizes the situation created by the award: Some 1,150,000 to 1,300,000 Romanians, or 48 per cent to over 50 per cent of the population of the ceded territory, depending upon whose statistics are used, remained north of the new frontier, while about 500,000 Hungarians (other Hungarian estimates go as high as 800,000, Romanian as low as 363,000) continued to reside in the south. In September–October 1944, Northern Transylvania was retaken by the armies of Romania and the Soviet Union; the territory remained under Soviet military administration until 9 March 1945, after which it became again part of Romania. The Treaty of Paris (1947) overturned the Vienna Award and recognized the territory of northern Transylvania as being part of Romania.

After the war, in 1952, a Magyar Autonomous Region was created in Romania by the communist authorities. The region was dissolved in 1968, when a new administrative organization of the country (still in effect today) replaced regions with counties. The communist authorities, and especially after Nicolae Ceaușescu's regime came to power, restarted the policy of Romanianization.

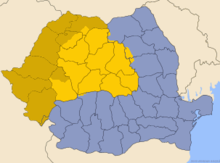

Today, "Transylvania proper" (bright yellow on the accompanying map) is included within the Romanian counties (județe) of Alba, Bistrița-Năsăud, Brașov, Cluj, Covasna, Harghita, Hunedoara, Mureș, Sălaj (partially) and Sibiu. In addition to "Transylvania proper", modern Transylvania includes Crișana and part of the Banat; these regions (dark yellow on the map) are in the counties of Arad, Bihor, Caraș-Severin, Maramureș, Sălaj (partially), Satu Mare, and Timiș.

Post-communist era

[edit]

In the aftermath of the Romanian Revolution of 1989, ethnic-based political parties were constituted by both the Hungarians, who founded the Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania, and by the Romanian Transylvanians, who founded the Romanian National Unity Party. Ethnic conflicts, however, never occurred on a significant scale, even though some violent clashes, such as the Târgu Mureș events of March 1990, did take place shortly after the fall of Ceaușescu regime.

In 1995, a basic treaty on the relations between Hungary and Romania was signed. In the treaty, Hungary renounced all territorial claims to Transylvania, and Romania reiterated its respect for the rights of its minorities. Relations between the two countries improved as first Hungary, then Romania, became EU members in the 2000s.

Politics

[edit]The Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR/RMDSZ) is the major representative of Hungarians in Romania, and is a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. The aim of the UDMR is to achieve local government, cultural and territorial autonomy and the right to self-determination for Hungarians. UDMR is a member of the European Democrat Union (EDU) and the European People's Party (EPP). Since 1996, the UDMR has been a member or supporter of every governmental coalition.

Political agreements have brought the gradual implementation of Hungarian in everyday life: Public administration Law 215/2002 stipulates "the use of national minority languages in public administration in settlements where minorities exceed 20% of the population"; minority ethnics will receive a copy of the documents in Romanian and a translation in their language; however, official documents are preserved by the local administration in Romanian only; local administration will provide inscriptions for the names of localities and public institutions under their authority, and display public interest announcements in the native language of the citizens of the respective ethnic minority under the same 20% rule.

Even though Romania co-signed the European laws for protecting minorities' rights, the implementation has not proved satisfactory to all members of Hungarian community. There is a movement by Hungarians both for an increase in autonomy and distinct cultural development. Initiatives proposed by various Hungarian political organizations include the creation of an "autonomous region" in the counties that form the Szekler region (Székelyföld), roughly corresponding to the territory of the former Hungarian Autonomous Province as well as the historical Szekler land that had been abolished by the Hungarian government in the second half of the 19th century, and the re-establishment of an independent state-funded Hungarian-language university.

However, the situation of the Hungarian minority in Romania has been seen by some as a model of cultural and ethnic diversity in the Balkan area:[11] In an address to the American people, President Clinton asked in the midst of the air war in Kosovo: Who is going to define the future of this part the world... Slobodan Milošević, with his propaganda machine and paramilitary forces which compel people to give up their country, identity, and property, or a state like Romania which has built a democracy respecting the rights of ethnic minorities?[12]

Notable Hungarians of Romania

[edit]Sports

[edit]Several ethnic Hungarians[13] have won Olympic medals for Romania.

- Iolanda Balaș (Jolanda Balázs) (2G) High-jump 1960 and 1964.

- Ileana Silai (Ilona Gergely) (S) 800m 1968[14]

- Ecaterina Szabo[15] (Katalin Szabó) (3G-individual, 1G-team 1S-individual) Gymnastics 1984

- Emilia Eberle (Hungarian-German)[16] (1S-individual, 1S-team) Gymnastics 1980

- Zita Funkenhauser, of mixed german-hungarian origin and hungarian-speaker(as her Germany-born children).

- Gabriela Szabo (1G, 1S, 1B) 1996, 2000 (father Hungarian)

- Corneliu Oros (B) Team-volleyball[17]

- Noemi Lung (Noemi Ildikó Lung) (S, B) Swimming 1984[18]

- Elena Horvat (Ilona Horvath) (G) team-rowing 1984[17][18]

- Viorica Ioja (Ibolya Jozsa)[19] (G, S) Team-rowing 84

- Aneta Mihaly (S) Team-rowing[17] 1984

- Herta Anitaș[17] (S, B) Team-rowing 1988

- Eniko Barabas (Enikö Barabás)[17](B) Team-rowing 2008

- Elisabeta Lazăr (Erzsébet Lázár)[19] (B) Team-rowing76

- Ladislau Lovrenschi (László Lavrenszki)[19] ( B) Team-rowing 72 (S) 88

- Ioan Pop (János Pap) (2B)[20][21] Team-sabre (B) 76, (B) 84

- Alexandru Nilca (Sándor Nyilka)[22][23] Team-sabre (B) 76

- Vilhelm Szabo (Vilmos Szabó) (B) Team-Sabre 1984[18]

- Monika Weber-Koszto (S) Team-foil 1984[17] (+ 1S, 2B for Germany)

- Marcela Zsak[18] (S) Team-foil 1984[17]´

- Rozalia Oros (Rozália Orosz)[19](S) Team-foil 1984

- Olga Orban-Szabo (Olga Orbán Szabó) (2B) Team women's´foil 1968,1972 (1S) Women's Foil Individual 1956[24][25][26]

- Ileana Gyulai-Drimba (Ilona Gyulai) (2B) Team-women's foil 1968,1972[27]

- Ecaterina Stahl-Iencic (Katalin Jencsik) (2B) Team-women's foil 1968,1972[27]

- Reka Zsofia Lazar-Szabo(1S, 1B) Team Women's´foil 1992, 1996[28]

- Simona Pop[29]

- Stefan Birtalan (István Bertalan) (1S, 2B) Team-Handball 1972, 1976,1980[30]

- Gabriel Kicsid (1S, 1B) Team-Handball 1972,1976[30]

- Iosif Boros (József Boros)[31](2B) Team-handball 1980 and 1984.[32]

- Stefan Tasnadi (István Tasnádi)[18] (S) weightlifting 1984[18][33]

- Valentin Silaghi (B) boxing 1980[14][17][32][dubious – discuss]

- Ladislau Simon (László Simon)[34] (B) wrestling 1976[35]

- Francisc Horvath[14] (Ferenc Horváth) (B) wrestling 1956[26]

Olympic chess players

[edit]- Janos Balogh

- Stefan Erdélyi (István Erdélyi)

- Alexandru Tyroler (Sándor Tyroler)

- Miklós Bródy

- Szidonia Vajda

Science

[edit]- Albert-László Barabási, physicist (network scientist)

- Tünde Fülöp, plasma physicist

- Veronica Vaida, chemist

Mathematics Olympics medalists

[edit]- George Lusztig: Silver 1962

- László Zsidó: Gold 1963

- András Némethi: Silver 1978

- Gabriel Nagy: Silver 1978

Physics Olympics medalists

[edit]- Adrian Mihai Devenyi: Gold 1982, Silver 1981

- Zoltan Gagyi-Palffy: Bronze 1986

- Peter Szerö: Gold 2009

- Vlad-Ștefan Oros: Gold 2023

Classical music

[edit]- Béla Bartok (composer)

- György Ligeti (composer)

- György Kurtág (composer)

- Sandor Vegh (violinist)

- Sándor Veress (composer)

- Péter Eötvös (composer/conductor)

- György Selmeczi (composer)

- Péter Csaba

- Emil Telmányi

- István Ruha (violinist)

- Johanna Martzy (violinist)

- Júlia Várady (soprano)

Literature

[edit]- Wass Albert (writer)

- Attila Bartis (writer)

- Miklós Bánffy (writer, politician)

- Ádám Bodor (writer)

- György Dragomán (writer)

- András Ferenc Kovács (poet)

- Sándor Kányádi (poet)

- Benő Karácsony (writer)

- Béla Markó (poet, politician)

- András Sütő (writer, playwright)

- Ignácz Rózsa (writer, actress)

- Csaba Székely (playwright, screenwriter)

- János Székely (writer, poet, playwright)

- Domokos Szilágyi (poet)

- István Szilágyi (writer)

- Áron Tamási (writer)

Actors of Hungarian descent

[edit]Religion

[edit]- Szilárd Bogdánffy (martyr)

- Áron Márton (servant of God)

- László Tőkés (pastor)

- László Böcskei (bishop)

Subgroups

[edit]Székelys

[edit]The Székely people are Hungarians who mainly live in an area known as Székely Land (Ținutul Secuiesc in Romanian), and who maintain a different set of traditions and different identity from that of other Hungarians in Romania. Based on the latest Romanian statistics (2011 Romanian census, 532 people declared themself "Székelys" rather than "Hungarians.".[36] The three counties of the unofficial Székely Land – Harghita, Covasna, and Mureș – have a combined ethnic Hungarian population of 609,033.

Csángós

[edit]

The Csángós (Romanian: Ceangău, pl. Ceangăi, Hungarian: Csángó, pl. Csángók) are people of Roman Catholic faith, some speaking a Hungarian dialect and some Romanian. They live mainly in the Bacău, Neamț and Iași counties, Moldavia region. Their homeland in Moldavia is known as Csángó Land. Some also live in Transylvania (around the Ghimeș-Palanca Pass and in the so-called Seven Villages) and in Oituz at Northern Dobruja. The Csango settled there between the 13th and 15th centuries and today, they are the only Hungarian-speaking ethnic group living to the east of the Carpathians.[citation needed]

The ethnic background of Csango is nevertheless disputed, since, due to its active connections to the neighboring Polish kingdom and to the Papal States, the Roman Catholic faith persisted in Moldavia throughout medieval times, long after Vlachs living in other Romanian provinces, closer to the Bulgarian Empire, had been completely converted to Eastern-Rite Christianity. Some Csango claim having Hungarian ancestry while others claim Romanian ancestry. The Hungarian-speaking Csangos have been subject to some violations of basic minority rights: Hungarian-language schools have been closed down over time, their political rights have been suppressed and they have even been subject to slow, forced nationalisation by various Romanian governments over the years, because the Romanian official institutions deem Csangos as a mere Romanian population that was Magyarized in certain periods of time.[citation needed]

Culture

[edit]

The number of Hungarian social and cultural organizations in Romania has greatly increased after the fall of communism, with more than 300 being documented a few years ago.[citation needed] There are also several puppet theatres.[citation needed] Professional Hungarian dancing in Romania is represented by the Maros Folk Ensemble (formerly State Szekler Ensemble) in Târgu Mureș, the Hargita Ensemble, and the Pipacsok Dance Ensemble.[citation needed] Other amateur popular theaters are also very important in preserving the cultural traditions.[citation needed]

While in the past the import of books was hindered, now there are many bookstores selling books written in Hungarian. Two public TV stations, TVR1 and TVR2, broadcast several Hungarian programs with good audiences also from Romanians.[citation needed] This relative scarcity is partially compensated by private Hungarian-language television and radio stations, like DUNA-TV which is targeted for the Hungarian minorities outside Hungary, particularly Transylvania. A new TV station entitled "Transylvania" is scheduled to start soon,[when?] the project is funded mostly by Hungary but also by Romania and EU and other private associations. There are currently around 60 Hungarian-language press publications receiving state support from the Romanian Government. While their numbers dropped as a consequence of economic liberalisation and competition, there are many others private funded by different Hungarian organizations. The Székely Region has many touristic facilities that attract Hungarian and other foreign tourists.

Education

[edit]According to Romania's minority rights law, Hungarians have the right to education in their native language, including as a medium of instruction. In localities where they make up more than 20% of the population they have the right to use their native language with local authorities.

According to the official data of the 1992 Romanian census, 98% of the total ethnic Hungarian population over the age of 12 has had some schooling (primary, secondary or tertiary), ranking them fourth among ethnic groups in Romania and higher than the national average of 95.3%. On the other hand, the ratio of Hungarians graduating from higher education is lower than the national average. The reasons are diverse, including a lack of Hungarian-speaking lecturers, particularly in areas without a significant population of Hungarians.

At Babeș-Bolyai University Cluj-Napoca, the largest state-funded tertiary education institution in Romania, more than 30% of courses are held in Hungarian. There is currently a proposal by local Hungarians, supported by the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (RMDSZ), to separate the Hungarian-language department from the institution, and form a new, Hungarian-only Bolyai University. The former Bolyai University was disbanded in 1959 by Romanian Communist authorities and united with the Romanian Babeș University to form the multilingual Babeș-Bolyai University that continues to exist today.

Other universities that offer study programs in Hungarian are the University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science and Technology of Târgu Mureș (public), Târgu Mureș University of Arts (public), Sapientia University (private) in Cluj-Napoca, Miercurea Ciuc and Târgu Mureș, Partium Christian University (private) in Oradea and Protestant Theological Institute of Cluj (private).

Identity and citizenship

[edit]Many Hungarians living in Transylvania were disconcerted when the referendum held in Hungary in 2004 on the issue of giving dual-citizenship to ethnic Hungarians living abroad failed to receive enough electoral attendance and the vote was uncertain. Some of them complain that when they are in Hungary, they are perceived as half-Romanians, and are considered as having differences in language and behaviour. However, a large proportion of Transylvanian Hungarians currently work or study in Hungary, usually on a temporary basis. After 1996, Hungarian-Romanian economic relations boomed, and Hungary is an important investor in Transylvania, with many cross-border firms employing both Romanians and Hungarians.[citation needed]

A proposal supported by the RMDSZ to grant Hungarian citizenship to Hungarians living in Romania but without meeting Hungarian-law residency requirements was narrowly defeated at a 2004 referendum in Hungary (the referendum failed only because there were not enough votes to make it valid).[37] After the failed vote, the leaders of the Hungarian ethnic parties in the neighboring countries formed the HTMSZF organization in January 2005, as an instrument lobbying for preferential treatment in the granting of Hungarian citizenship.[38]

In 2010 some amendments were passed in Hungarian law facilitating an accelerated naturalization process for ethnic Hungarians living abroad; among other changes, the residency-in-Hungary requirement was waived.[39] According to a RMDSZ poll conducted that year, over 85 percent of Romania's ethnic Hungarians were eager to apply for Hungarian citizenship.[40] Romania's President Traian Băsescu declared in October 2010 that "We have no objections to the adoption by the Hungarian government and parliament of a law making it easier to grant Hungarian citizenship to ethnic Hungarians living abroad."[41]

Between 2011 and 2012, 200,000 applicants took advantage of the new, accelerated naturalization process;[42] there were another 100,000 applications pending in the summer of 2012.[43] As of February 2013, the Hungarian government has granted citizenship to almost 400,000 Hungarians 'beyond the borders'.[44] In April 2013, the Hungarian government announced that 280,000 of these were Romanian citizens.[45]

Population

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 1,425,507 | — |

| 1941 | 407,188 | −71.4% |

| 1948 | 1,499,851 | +268.3% |

| 1956 | 1,587,675 | +5.9% |

| 1966 | 1,619,592 | +2.0% |

| 1977 | 1,713,928 | +5.8% |

| 1992 | 1,620,199 | −5.5% |

| 2002 | 1,431,807 | −11.6% |

| 2011 | 1,227,623 | −14.3% |

| 2022 | 1,002,151 | −18.4% |

| Romanian census data | ||

According to the 2011 census,[46] the total population of the ethnic Hungarian community in Romania is as follows:

| County | Hungarians | Percent of county population |

Percent of Hungarians in Romania |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harghita | 257,707 | 85.21% | 20.99% |

| Covasna | 150,468 | 73.74% | 12.25% |

| Mureș | 200,858 | 38.09% | 16.36% |

| Satu Mare | 112,580 | 34.65% | 9.17% |

| Bihor | 138,213 | 25.27% | 11.25% |

| Sălaj | 50,177 | 23.35% | 4.08% |

| Cluj | 103,591 | 15.93% | 8.43% |

| Arad | 36,568 | 9.03% | 2.97% |

| Brașov | 39,661 | 7.69% | 3.23% |

| Maramureș | 32,618 | 7.22% | 2.65% |

| Timiș | 35,295 | 5.57% | 2.87% |

| Bistrița-Năsăud | 14,350 | 5.23% | 1.16% |

| Alba | 14,849 | 4.61% | 1.21% |

| Hunedoara | 15,900 | 4.04% | 1.29% |

| Sibiu | 10,893 | 2.93% | 0.88% |

| Caraș-Severin | 3,276 | 1.19% | 0.26% |

| Bacău | 4,373 | 0.75% | 0.35% |

| Bucharest | 3,463 | 0.21% | 0.28% |

| Total | 1,222,650 | — | 6.1% nationwide |

The remaining 4,973 (0.4%) ethnic Hungarians live in the other counties of Romania, where they make up less than 0.1% of the total population.

Religion

[edit]

In 2002, 46.5% of Romania's Hungarians were Reformed, 41% Roman Catholic, 4.5% Unitarian and 2% Romanian Orthodox. A further 4.7% belonged to various other Christian denominations.[47]

In 2011, 45.9% of Romania's Hungarians were Reformed, 40.8% Roman Catholic, 4.5% Unitarian and 2.1% Romanian Orthodox. A further 5.8% belonged to various other Christian denominations.[48] Around 0.25 percent of the Hungarians were atheist.

In 2021, 45.3% of Romania's Hungarians were Reformed, 40.4% Roman Catholic, 4.6% Unitarian, 1.9% Romanian Orthodox, 1.2% Greek Catholic, 1.1% Baptist and 1% Lutheran. Adherents of other – predominantly Christian – denominations (e.g., Adventists, Pentecostals and Jehovah's Witnesses) accounted for less than 1% together.[49]

Hungarian Heritage in Transylvania, Romania

[edit]-

Alba Iulia (Gyulafehérvár) Catholic cathedral, Romanesque, 12th century

-

Rimetea (Torockó)

-

Târgu Mureș (Marosvásárhely), Hungarian Art Nouveau

-

Dârjiu (Székelyderzs), Fortified Unitarian Church

-

Dârjiu, The murals of the Unitarian church show the legend of Ladislaus I of Hungary.

-

Odorheiu Secuiesc (Székelyudvarhely), Franciscan Church

-

Târgu Mureș (Marosvásárhely), Catholic Church (former Jesuit Church)

-

Székely Gate

-

Inlăceni (Énlaka), Hungarian runic script (Old Hungarian script)

-

Oradea (Nagyvárad), Catholic Cathedral and Ladislaus I of Hungary Statue

-

Fortified church of Mihăileni, Harghita County

See also

[edit]- Romanians in Hungary

- List of towns in Romania by ethnic Hungarian population

- Romanian Hearth Union

- Hungarian Cultural Days of Cluj

- Transylvanianism

References

[edit]- ^ a b Széchely, István (3 January 2023). "Mintha városok ürültek volna ki" [As if cities had been emptied]. Székelyhon (in Hungarian). Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ "Comunicat de presă privind rezultatele definitive ale Recensământului Populației și Locuințelor – 2011" (PDF). Recensamantromania.ro (in Romanian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio, edited by Gy. Moravcsik and translated by R. J. H. Jenkins, Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, Washington D. C., 1993 pp. 175)

- ^ Fine, Jr., John V. A. (1994). The Early Medieval Balkans – A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. The University of Michigan Press. p. 139. ISBN 0-472-08149-7

- ^ a b "Transylvania". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ "Diploma Leopoldinum – Transylvanian history". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "John Hunyadi: Hungary in American History Textbooks". Andrew L. Simon. Corvinus Library Hungarian History. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Kovrig, Bennett (2000), Partitioned nation: Hungarian minorities in Central Europe, in: Michael Mandelbaum (ed.), The new European Diasporas: National Minorities and Conflict in Eastern Europe, New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, pp. 19–80.

- ^ Iancu, Mariana (25 April 2018). "Fascinanta poveste a ceangăilor care au ridicat un sat în pustiul dobrogean stăpânit de șerpi: "Veneau coloniști și ne furau tot, până și lanțul de la fântână"". Adevărul (in Romanian).

- ^ Hitchins, Keith (1994), Rumania: 1866–1947 (Oxford History of Modern Europe). Oxford University Press

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld – Romania: Ethnic Hungarians (January 2001 – January 2006)". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Tom Gallagher, "Modern Romania: the end of communism, the failure of democratic reform, and the theft of a nation", p. 216, NYU Press, 2005

- ^ Mircea Dominte (6 September 2013). "Origini ungurești pentru medalii olimpice românești" (in Romanian). fanatik.ro.</ref

- ^ a b c "Udvardy Frigyes – A romániai magyar kisebbség történeti kronológiája 1990–2009". udvardy.adatbank.transindex.ro. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Ennyivel tartozunk (Az egyetemes magyar sportért) – 2010. november 1., hétfő -". 3szek.ro. November 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Gymn Forum: Emilia Eberle Biography". Gymn-forum.net. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Origini ungurești pentru medalii olimpice românești – Fanatik – Sport si pariuri". Fanatik.ro. 6 September 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Hungarian Olympic Triumph: 1984, Los Angeles". Americanhungarianfederation.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Egyetemes magyar sport – Lapozgató (53.) – 2013. december 30., hétfő -". 3szek.ro. 30 December 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Ioan Pop Biography and Olympic Results | Olympics at Sports-Reference.com". Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ "Vívó világversenyek kulisszatitkai". Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Egyetemes magyar sport – Lapozgató (45.) – 2013. november 4., hétfő -". 3szek.ro. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Alexandru Nilca Biography and Olympic Results | Olympics at Sports-Reference.com". Archived from the original on 21 September 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ "Hungarian Olympic Triumph: 1956 Melbourne". Americanhungarianfederation.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "KILLYÉNI ANDRÁS : SZABÓ-ORBÁN OLGA : A L Á N Y, A K I M E G H Ó D Í TOT TA A V I L Á G OT" (PDF). Mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Hungarian Olympic Triumph: 1956 Melbourne". www.americanhungarianfederation.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Hungarian Olympic Triumph: 1968 Mexico City". Americanhungarianfederation.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Frenkiebig. "Erdélyi Örmény Gyökerek Kulturális Egyesület". Magyarormeny.hu. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Csipler Attilától Simona Popig – azaz szatmári érmek és rekordok az olimpiák történelmében". szatmar.ro. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Hungarian Olympic Triumph: 1972 Munich". Americanhungarianfederation.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Iosif Boroş Bio, Stats, and Results | Olympics at Sports-Reference.com". Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Hungarian Olympic Triumph: 1980 Moscow (Magyar Olimpiai Bajnokok)". Americanhungarianfederation.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Ştefan Taşnadi Bio, Stats, and Results | Olympics at Sports-Reference.com". Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ "Ladislau Şimon Biography and Olympic Results | Olympics at Sports-Reference.com". Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ "Hungarian Olympic Triumph: 1976 Montreal (magyar olimpiai bajnokok listája)". Americanhungarianfederation.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "CESCH- Recensamant Populatie 2011 CV Hr". Scribd. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Rogers Brubaker (2006). Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town. Princeton University Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-691-12834-4.

- ^ Tristan James Mabry; John McGarry; Margaret Moore; Brendan O'Leary (30 May 2013). Divided Nations and European Integration. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8122-4497-7.

- ^ Mária M. Kovács, Judit Tóth, Country report: Hungary Archived 30 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Revised and updated April 2013, EUDO Citizenship Observatory, page 1 and 7

- ^ Ethnic Hungarians in Romania keen to get Hungarian passport, EUobserver, 26.05.2010

- ^ Romania backs Hungarian citizenship law, 18 October 2010, AFP text syndicated to eubusiness.com.

- ^ Mária M. Kovács, Judit Tóth, Country report: Hungary Archived 30 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Revised and updated April 2013, EUDO Citizenship Observatory, page 11

- ^ Mária M. Kovács, Judit Tóth, Country report: Hungary Archived 30 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Revised and updated April 2013, EUDO Citizenship Observatory, page 18

- ^ Hungary and Romania. Flag wars, 21 Feb 2013, The Economist

- ^ Emil Groza (5 Aprilie 2013) Aproape 300.000 de români cer cetatenie maghiara, Radio România Actualități

- ^ "Recensamantul Populatiei si Locuintelor 2011: Populația stabilă după etnie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune". Recensamantromania.ro. Archived from the original (XLS) on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Populația după etnie și religie, pe medii" (PDF). Insse.ro. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Rezultate 2011 – Recensamantul Populatiei si Locuintelor" (in Romanian). Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Chirmiciu, András (19 January 2023). "Részleges közösségi radiográfia" [Partial community radiography]. Nyugati Jelen (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Bell, Andrew (September 1996). "The Hungarians in Romania since 1989". Nationalities Papers. 24 (3): 491–507. doi:10.1080/00905999608408462. S2CID 153338041.

- Culic, Irina (May 2006). "Dilemmas of belonging: Hungarians from Romania". Nationalities Papers. 34 (2): 175–200. doi:10.1080/00905990600617839. S2CID 154722674.

External links

[edit]- Multiculturalism debated Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Editorial about the Hungarian University in Cluj (Nine O'Clock, an English-language daily [e]newspaper)

- The Hungarian National Theater in Cluj, one of the most prestigious Hungarian theaters in Transylvania

- Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania, the main Hungarian ethnic party website