Human history

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

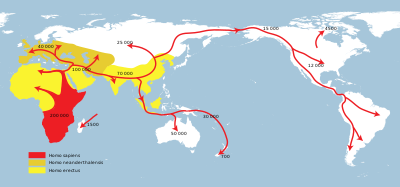

Human history is the record of humankind from prehistory to the present. Modern humans evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago and initially lived as hunter-gatherers. They migrated out of Africa during the Last Ice Age and had spread across Earth's continental land except Antarctica by the end of the Ice Age 12,000 years ago. Soon afterward, the Neolithic Revolution in West Asia brought the first systematic husbandry of plants and animals, and saw many humans transition from a nomadic life to a sedentary existence as farmers in permanent settlements. The growing complexity of human societies necessitated systems of accounting and writing.

These developments paved the way for the emergence of early civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley, and China, marking the beginning of the ancient period in 3500 BCE. These civilizations supported the establishment of regional empires and acted as a fertile ground for the advent of transformative philosophical and religious ideas, initially Hinduism during the late Bronze Age and Buddhism, Confucianism, Greek philosophy, Jainism, Judaism, Taoism, and Zoroastrianism during the Axial Age. The subsequent post-classical period, from about 500 to 1500 CE, witnessed the rise of Islam and the continued spread and consolidation of Christianity while civilization expanded to new parts of the world and trade between societies increased. These developments were accompanied by the rise and decline of major empires, such as the Byzantine Empire, the Islamic Caliphates, the Mongol Empire, and various Chinese dynasties. This period's invention of gunpowder and of the printing press greatly affected subsequent history.

During the early modern period, spanning from approximately 1500 to 1800 CE, European powers explored and colonized regions worldwide, intensifying cultural and economic exchange. This era saw substantial intellectual, cultural, and technological advances in Europe driven by the Renaissance, the Reformation in Germany giving rise to Protestantism, the Scientific Revolution, and the Enlightenment. By the 18th century, the accumulation of knowledge and technology had reached a critical mass that brought about the Industrial Revolution, substantial to the Great Divergence, and began the modern period starting around 1800 CE. The rapid growth in productive power further increased international trade and colonization, linking the different civilizations in the process of globalization, and cemented European dominance throughout the 19th century. Over the last quarter-millennium, which included two devastating world wars, there has been a great acceleration in many spheres, including human population, agriculture, industry, commerce, scientific knowledge, technology, communications, military capabilities, and environmental degradation.

The study of human history relies on insights from academic disciplines including history, archaeology, anthropology, linguistics, and genetics. To provide an accessible overview, researchers divide human history by a variety of periodizations.

Prehistory

Human origins

Humans evolved in Africa from great apes through the lineage of hominins, which arose 7–5 million years ago.[1] The ability to walk on two legs emerged in early hominins after the split from chimpanzees, as an adaptation possibly associated with a shift from forest to savanna habitats.[2] Hominins began to use rudimentary stone tools c. 3.3 million years ago,[a] marking the advent of the Paleolithic era.[6]

The genus Homo evolved from Australopithecus.[7] The earliest record of Homo is the 2.8 million-year-old specimen LD 350-1 from Ethiopia,[8] and the earliest named species is Homo habilis which evolved by 2.3 million years ago.[9] The most important difference between Homo habilis and Australopithecus was a 50% increase in brain size.[10] H. erectus[b] evolved about 2 million years ago[11][c] and was the first hominin species to leave Africa and disperse across Eurasia.[13] Perhaps as early as 1.5 million years ago, but certainly by 250,000 years ago, hominins began to use fire for heat and cooking.[14]

Beginning about 500,000 years ago, Homo diversified into many new species of archaic humans such as the Neanderthals in Europe, the Denisovans in Siberia, and the diminutive H. floresiensis in Indonesia.[15] Human evolution was not a simple linear or branched progression but involved interbreeding between related species.[16] Genomic research has shown that hybridization between substantially diverged lineages was common in human evolution.[17] DNA evidence suggests that several genes of Neanderthal origin are present among all non-sub-Saharan African populations. Neanderthals and other hominins, such as Denisovans, may have contributed up to 6% of their genome to present-day non-sub-Saharan African humans.[18]

Early humans

Homo sapiens emerged in Africa around 300,000 years ago[d] from the species Homo heidelbergensis.[e][20] Humans continued to develop over the succeeding millennia, and by 100,000 years ago, were using jewelry and ocher to adorn the body.[21] By 50,000 years ago, they buried their dead, used projectile weapons, and engaged in seafaring.[22] One of the most important changes (the date of which is unknown) was the development of syntactic language, which dramatically improved the human ability to communicate.[23] Signs of early artistic expression can be found in the form of cave paintings and sculptures made from ivory, stone, and bone, implying a form of spirituality generally interpreted as animism[24] or shamanism.[25] The earliest known musical instruments besides the human voice are bone flutes from the Swabian Jura in Germany, dated around 40,000 years old.[26] Paleolithic humans lived as hunter-gatherers and were generally nomadic.[27]

The migration of anatomically modern humans out of Africa took place in multiple waves beginning 194,000–177,000 years ago.[28][f] The dominant view among scholars is that the early waves of migration died out and all modern non-Africans are descended from a single group that left Africa 70,000–50,000 years ago.[32][g] H. sapiens proceeded to colonize all the continents and larger islands, arriving in Australia 65,000 years ago,[34] Europe 45,000 years ago,[35] and the Americas 21,000 years ago.[36] These migrations occurred during the most recent Ice Age, when various temperate regions of today were inhospitable.[37] Nevertheless, by the end of the Ice Age some 12,000 years ago, humans had colonized nearly all ice-free parts of the globe.[38] Human expansion coincided with both the Quaternary extinction event and the Neanderthal extinction.[39] These extinctions were probably caused by climate change, human activity, or a combination of the two.[40]

Rise of agriculture

Beginning around 10,000 BCE, the Neolithic Revolution marked the development of agriculture, which fundamentally changed the human lifestyle.[41] Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe,[42] and included a diverse range of taxa, in at least 11 separate centers of origin.[43] Cereal crop cultivation and animal domestication had occurred in Mesopotamia by at least 8500 BCE in the form of wheat, barley, sheep, and goats.[44] The Yangtze River Valley in China domesticated rice around 8000–7000 BCE; the Yellow River Valley may have cultivated millet by 7000 BCE.[45] Pigs were the most important domesticated animal in early China.[46] People in Africa's Sahara cultivated sorghum and several other crops between 8000 and 5000 BCE,[h] while other agricultural centers arose in the Ethiopian Highlands and the West African rainforests.[48] In the Indus River Valley, crops were cultivated by 7000 BCE and cattle were domesticated by 6500 BCE.[49] In the Americas, squash was cultivated by at least 8500 BCE in South America, and domesticated arrowroot appeared in Central America by 7800 BCE.[50] Potatoes were first cultivated in the Andes of South America, where the llama was also domesticated.[51] It is likely that women played a central role in plant domestication throughout these developments.[52]

Various explanations of the causes of the Neolithic Revolution have been proposed.[53] Some theories identify population growth as the main factor, leading people to seek out new food sources. Others see population growth not as the cause but as the effect of the associated improvements in food supply.[54] Further suggested factors include climate change, resource scarcity, and ideology.[55] The transition to agriculture created food surpluses that could support people not directly engaged in food production,[56] permitting far denser populations and the creation of the first cities and states.[57]

Cities were centers of trade, manufacturing, and political power.[58] They developed mutually beneficial relationships with their surrounding countrysides, receiving agricultural products and providing manufactured goods and varying degrees of political control in return.[59] Pastoral societies based on nomadic animal herding also developed, mostly in dry areas unsuited for plant cultivation such as the Eurasian Steppe or the African Sahel.[60] Conflict between nomadic herders and sedentary agriculturalists was frequent and became a recurring theme in world history.[61]

Metalworking was first used in the creation of copper tools and ornaments around 6400 BCE.[48] Gold and silver soon followed, primarily for use in ornaments.[48] The first signs of bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, date to around 4500 BCE,[62] but the alloy did not become widely used until the 3rd millennium BCE.[63]

Ancient history

Cradles of civilization

The Bronze Age saw the development of cities and civilizations.[64] Early civilizations arose close to rivers, first in Mesopotamia (3300 BCE) with the Tigris and Euphrates,[65] followed by the Egyptian civilization along the Nile River (3200 BCE),[66] the Norte Chico civilization in coastal Peru (3100 BCE),[67] the Indus Valley civilization in Pakistan and northwestern India (2500 BCE),[68] and the Chinese civilization along the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers (2200 BCE).[69][i]

These societies developed a number of shared characteristics, including a central government, a complex economy and social structure, and systems for keeping records.[72] These cultures variously invented the wheel,[73] mathematics,[74] bronze-working,[75] sailing boats,[76] the potter's wheel,[75] woven cloth,[77] construction of monumental buildings,[77] and writing.[78] Polytheistic religions developed, centered on temples where priests and priestesses performed sacrificial rites.[79]

Writing facilitated the administration of cities, the expression of ideas, and the preservation of information.[80] It may have independently developed in at least four ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia (3300 BCE),[81] Egypt (around 3250 BCE),[82] China (1200 BCE),[83] and lowland Mesoamerica (by 650 BCE).[84] The earliest system of writing[j] was the Mesopotamian cuneiform script, which began as a system of pictographs, whose pictorial representations eventually became simplified and more abstract.[86][k] Other influential early writing systems include Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Indus script.[88] In China, writing was first used during the Shang dynasty (1766–1045 BCE).[89]

Transport was facilitated by waterways, including rivers and seas, which fostered the projection of military power and the exchange of goods, ideas, and inventions.[90] The Bronze Age also saw new land technologies, such as horse-based cavalry and chariots, that allowed armies to move faster.[91] Trade became increasingly important as urban societies exchanged manufactured goods for raw materials from distant lands, creating vast commercial networks and the beginnings of archaic globalization.[92] Bronze production in West Asia, for example, required the import of tin from as far away as England.[93]

The growth of cities was often followed by the establishment of states and empires.[94] In Egypt, the initial division into Upper and Lower Egypt was followed by the unification of the whole valley around 3100 BCE.[95] Around 2600 BCE, the Indus Valley civilization built major cities at Harappa and Mohenjo-daro.[96] Mesopotamian history was characterized by frequent wars between city-states, leading to shifts in hegemony from one city to another.[97] In the 25th–21st centuries BCE, the empires of Akkad and the Neo-Sumerians arose in this area.[98] In Crete, the Minoan civilization emerged by 2000 BCE and is regarded as the first civilization in Europe.[99]

Over the following millennia, civilizations developed across the world.[100] By 1600 BCE, Mycenaean Greece began to develop.[101] It flourished until the Late Bronze Age collapse that affected many Mediterranean civilizations between 1300 and 1000 BCE.[102] The foundations of many cultural aspects in India were laid in the Vedic period (1750–600 BCE), including the emergence of Hinduism.[103][l] From around 550 BCE, many independent kingdoms and republics known as the Mahajanapadas were established across the subcontinent.[105]

Speakers of the Bantu languages began expanding across Central, East, and Southern Africa as early as 3000 BCE until 1000 CE.[106] Their expansion and encounters with other groups resulted in the displacement of the Pygmy peoples and the Khoisan, and in the spread of mixed farming and ironworking throughout sub-Saharan Africa, laying the foundations for later states.[107]

The Lapita culture emerged in the Bismarck Archipelago near New Guinea around 1500 BCE and colonized many uninhabited islands of Remote Oceania, reaching as far as Samoa by 700 BCE.[108]

In the Americas, the Norte Chico culture emerged in Peru around 3100 BCE.[67] The Norte Chico built public monumental architecture at the city of Caral, dated 2627–1977 BCE.[109] The later Chavín polity is sometimes described as the first Andean state,[110] centered on the religious site at Chavín de Huantar.[111] Other important Andean cultures include the Moche, whose ceramics depict many aspects of daily life, and the Nazca, who created animal-shaped designs in the desert called Nazca lines.[112] The Olmecs of Mesoamerica developed by about 1200 BCE[113] and are known for the colossal stone heads that they carved from basalt.[114] They also devised the Mesoamerican calendar that was used by later cultures such as the Maya and Teotihuacan.[115] Societies in North America were primarily egalitarian hunter-gatherers, supplementing their diet with the plants of the Eastern Agricultural Complex.[116] They built earthworks such as Watson Brake (4000 BCE) and Poverty Point (3600 BCE), both in Louisiana.[117]

Axial Age

From 800 to 200 BCE,[118] the Axial Age saw the emergence of transformative philosophical and religious ideas that developed in many different places mostly independently of each other.[119] Chinese Confucianism,[120] Indian Buddhism and Jainism,[121] and Jewish monotheism all arose during this period.[122] Persian Zoroastrianism began earlier, perhaps around 1000 BCE, but was institutionalized by the Achaemenid Empire during the Axial Age.[123] New philosophies took hold in Greece during the 5th century BCE, epitomized by thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle.[124] The first Olympic Games were held in 776 BCE, marking a period known as "classical antiquity".[125] In 508 BCE, the world's first democratic system of government was instituted in Athens.[126]

Axial Age ideas shaped subsequent intellectual and religious history. Confucianism was one of the three schools of thought that came to dominate Chinese thinking, along with Taoism and Legalism.[127] The Confucian tradition, which would become particularly influential, looked for political morality not to the force of law but to the power and example of tradition.[128] Confucianism would later spread to Korea and Japan.[129] Buddhism reached China in about the 1st century CE[130] and spread widely, with 30,000 Buddhist temples in northern China alone by the 7th century CE.[131] Buddhism became the main religion in much of South, Southeast, and East Asia.[132] The Greek philosophical tradition[133] diffused throughout the Mediterranean world and as far as India, starting in the 4th century BCE after the conquests of Alexander the Great of Macedon.[134] Both Christianity and Islam developed from the beliefs of Judaism.[135]

Regional empires

The millennium from 500 BCE to 500 CE saw a series of empires of unprecedented size develop. Well-trained professional armies, unifying ideologies, and advanced bureaucracies created the possibility for emperors to rule over large domains whose populations could attain numbers upwards of tens of millions of subjects.[136] International trade also expanded, most notably the massive trade routes in the Mediterranean Sea, the maritime trade web in the Indian Ocean, and the Silk Road.[137]

The kingdom of the Medes helped to destroy the Assyrian Empire in tandem with the nomadic Scythians and the Babylonians.[138] Nineveh, the capital of Assyria, was sacked by the Medes in 612 BCE.[139] The Median Empire gave way to successive Iranian states, including the Achaemenid (550–330 BCE),[140] Parthian (247 BCE – 224 CE),[141] and Sasanian Empires (224–651 CE).[142]

Two major empires began in modern-day Greece. In the late 5th century BCE, several Greek city states checked the Achaemenid Persian advance in Europe through the Greco-Persian Wars. These wars were followed by the Golden Age of Athens, the seminal period of ancient Greece that laid many of the foundations of Western civilization, including the first theatrical performances.[143] The wars led to the creation of the Delian League, founded in 477 BCE,[144] and eventually the Athenian Empire (454–404 BCE), which was defeated by a Spartan-led coalition during the Peloponnesian War.[145] Philip of Macedon unified the Greek city-states into the Hellenic League and his son Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) founded an empire extending from present-day Greece to India.[146] The empire divided into several successor states shortly after his death, resulting in the founding of many cities and the spread of Greek culture throughout conquered regions, a process referred to as Hellenization.[147] The Hellenistic period lasted from the death of Alexander in 323 BCE until 31 BCE, when Ptolemaic Egypt fell to Rome.[148]

In Europe, the Roman Republic was founded in the 6th century BCE[149] and began expanding its territory in the 3rd century BCE.[150] Prior to this, the Carthaginian Empire had dominated the Mediterranean, however lost three successive wars to the Romans. The Republic became an empire and by the time of Augustus (63 BCE – 14 CE), it had established dominion over most of the Mediterranean Sea.[151] The empire continued to grow and reached its peak under Trajan (53–117 CE), controlling much of the land from England to Mesopotamia.[152] The two centuries that followed are known as the Pax Romana, a period of unprecedented peace, prosperity, and political stability in most of Europe.[153] Christianity was legalized by Constantine I in 313 CE after three centuries of imperial persecution. It became the sole official religion of the empire in 380 CE while the emperor Theodosius outlawed pagan religions in 391–392 CE.[154]

In South Asia, Chandragupta Maurya founded the Maurya Empire (320–185 BCE), which flourished under Ashoka the Great.[155] From the 4th to 6th centuries CE, the Gupta Empire oversaw the period referred to as ancient India's golden age.[156] The resulting stability helped usher in a flourishing period for Hindu and Buddhist culture in the 4th and 5th centuries, as well as major advances in science and mathematics.[157] In South India, three prominent Dravidian kingdoms emerged: the Cheras, Cholas, and Pandyas.[158]

In China, Qin Shi Huang put an end to the chaotic Warring States period by uniting all of China under the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE).[159] Qin Shi Huang was an adherent of the Legalist school of thought and he displaced the hereditary aristocracy by creating an efficient system of administration staffed by officials appointed according to merit.[160] The harshness of the Qin dynasty led to rebellions and the dynasty's fall.[161] It was followed by the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), which combined the Legalist bureaucratic system with Confucian ideals.[162] The Han dynasty was comparable in power and influence to the Roman Empire that lay at the other end of the Silk Road.[163] As economic prosperity fueled their military expansion, the Han conquered parts of Mongolia, Central Asia, Manchuria, Korea, and northern Vietnam.[164] As with other empires during the classical period, Han China advanced significantly in the areas of government, education, science, and technology.[165] The Han invented the compass, one of China's Four Great Inventions.[166]

In Africa, the Kingdom of Kush prospered through its interactions with both Egypt and sub-Saharan Africa.[167] It ruled Egypt as the Twenty-fifth Dynasty from 712 to 650 BCE, then continued as an agricultural and trading state based in the city of Meroë until the fourth century CE.[168] The Kingdom of Aksum, centered in present-day Ethiopia, established itself by the 1st century CE as a major trading empire, dominating its neighbors in South Arabia and Kush and controlling the Red Sea trade.[169] It minted its own currency and carved enormous monolithic stelae to mark its emperors' graves.[170]

Successful regional empires were also established in the Americas, arising from cultures established as early as 2500 BCE.[171] In Mesoamerica, vast pre-Columbian societies were built, the most notable being the Zapotec civilization (700 BCE – 1521 CE),[172] and the Maya civilization, which reached its highest state of development during the Mesoamerican classic period (c. 250–900 CE),[173] but continued throughout the post-classic period.[174] The great Maya city-states slowly rose in number and prominence, and Maya culture spread throughout the Yucatán and surrounding areas.[175] The Maya developed a writing system and used the concept of zero in their mathematics.[176] West of the Maya area, in central Mexico, the city of Teotihuacan prospered due to its control of the obsidian trade.[177] Its power peaked around 450 CE, when its 125,000–150,000 inhabitants made it one of the world's largest cities.[178]

Technology developed sporadically in the ancient world.[179] There were periods of rapid technological progress, such as the Greco-Roman era in the Mediterranean region.[180] Greek science, technology, and mathematics are generally considered to have reached their peak during the Hellenistic period, typified by devices such as the Antikythera mechanism.[181] There were also periods of technological decay, such as the Roman Empire's decline and fall and the ensuing early medieval period.[182] Two of the most important innovations were paper (China, 1st and 2nd centuries CE)[183] and the stirrup (India, 2nd century BCE and Central Asia, 1st century CE),[184] both of which diffused widely throughout the world. The Chinese learned to make silk and built massive engineering projects such as the Great Wall of China and the Grand Canal.[185] The Romans were also accomplished builders, inventing concrete, perfecting the use of arches in construction, and creating aqueducts to transport water over long distances to urban centers.[186]

Most ancient societies practiced slavery,[187] which was particularly prevalent in Athens and Rome, where slaves made up a large proportion of the population and were foundational to the economy.[188] Patriarchy was also common, with men controlling more political and economic power than women.[189]

Declines, falls, and resurgence

The ancient empires faced common problems associated with maintaining huge armies and supporting a central bureaucracy.[190] In Rome and Han China, the state began to decline, and barbarian pressure on the frontiers hastened internal dissolution.[190] The Han dynasty fell into civil war in 220 CE, beginning the Three Kingdoms period, while its Roman counterpart became increasingly decentralized and divided about the same time in what is known as the Crisis of the Third Century.[191] From the Eurasian Steppe, horse-based nomads dominated a large part of the continent.[192] The development of the stirrup and the use of horse archers made the nomads a constant threat to sedentary civilizations.[193]

In the 4th century CE, the Roman Empire split into western and eastern regions, with usually separate emperors.[194] The Western Roman Empire fell in 476 CE to German influence under Odoacer during the Migration Period of the Germanic peoples.[194] The Eastern Roman Empire, known as the Byzantine Empire, was more long-lasting.[195] In China, dynasties rose and fell, but, in sharp contrast to the Mediterranean-European world, political unity was always eventually restored.[196] After the fall of the Eastern Han dynasty and the demise of the Three Kingdoms, nomadic tribes from the north began to invade, causing many Chinese people to flee southward.[197]

Post-classical history

The post-classical period, dated roughly from 500 to 1500 CE,[m] was characterized by the rise and spread of major religions while civilization expanded to new parts of the world and trade between societies intensified.[200] From the 10th to 13th centuries, the Medieval Warm Period in the northern hemisphere aided agriculture and led to population growth in parts of Europe and Asia.[201] It was followed by the Little Ice Age, which, along with the plagues of the 14th century, put downward pressure on the population of Eurasia.[201] Major inventions of the period were gunpowder, guns, and printing, all of which originated in China.[202]

The post-classical period encompasses the early Muslim conquests, the Islamic Golden Age, and the commencement and expansion of the Arab slave trade, followed by the Mongol invasions and the founding of the Ottoman Empire.[203] South Asia had a series of middle kingdoms, followed by the establishment of Islamic empires in India.[204]

In West Africa, the Mali and Songhai Empires rose.[205] On the southeast coast of Africa, Arabic ports were established where gold, spices, and other commodities were traded. This allowed Africa to join the Southeast Asia trading system, bringing it contact with Asia; this resulted in the Swahili culture.[206]

China experienced the relatively successive Sui, Tang, Song, Yuan, and early Ming dynasties.[207] Middle Eastern trade routes along the Indian Ocean, and the Silk Road through the Gobi Desert, provided limited economic and cultural contact between Asian and European civilizations.[179] During the same period, civilizations in the Americas, such as the Mississippians,[208] Aztecs,[209] Maya,[210] and Inca reached their zenith.[211]

Europe

Since at least the 4th century, Christianity has played a prominent role in shaping the culture, values, and institutions of Western civilization, primarily through Catholicism and later also Protestantism.[212] Europe during the Early Middle Ages was characterized by depopulation, deurbanization, and barbarian invasions, all of which had begun in late antiquity.[213] The barbarian invaders formed their own new kingdoms in the remains of the Western Roman Empire.[214] Although there were substantial changes in society and political structures, most of the new kingdoms incorporated existing Roman institutions.[215] Christianity expanded in Western Europe, and monasteries were founded.[216] In the 7th and 8th centuries, the Franks under the Carolingian dynasty established an empire covering much of Western Europe;[217] it lasted until the 9th century, when it succumbed to pressure from new invaders—the Vikings, Magyars, and Arabs.[218] It split into West Francia and East Francia, which developed into middle ages France and the Holy Roman Empire, middle ages Germany. During the Carolingian era, churches developed a form of musical notation called neume which became the basis for the modern notation system.[219] Kievan Rus' expanded from its capital in Kiev to become the largest state in Europe by the 10th century. In 988, Vladimir the Great adopted Orthodox Christianity as the state religion.[220]

During the High Middle Ages, which began after 1000, the population of Europe increased as technological and agricultural innovations allowed trade to flourish and crop yields to increase.[221] The establishment of the feudal system affected the structure of medieval society. It included manorialism, the organization of peasants into villages that owed rents and labor service to nobles, and vassalage, a political structure whereby knights and lower-status nobles owed military service to their overlords in return for the right to rents from lands and manors.[222] Kingdoms became more centralized after the decentralizing effects of the breakup of the Carolingian Empire.[223] In 1054, the Great Schism between the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches led to the prominent cultural differences between Western and Eastern Europe.[224] The Crusades were a series of religious wars waged by Christians to wrest control of the Holy Land from the Muslims and succeeded for long enough to establish some Crusader states in the Levant.[225] Italian merchants imported slaves to work in households or in sugar processing.[226] Intellectual life was marked by scholasticism and the founding of universities, while the building of Gothic cathedrals and churches was one of the outstanding artistic achievements of the age.[227] The Middle Ages witnessed the first sustained urbanization of Northern and Western Europe and lasted until the beginning of the early modern period in the 16th century.[228]

The Mongols reached Europe in 1236 and conquered Kievan Rus', along with briefly invading Poland and Hungary.[229] Lithuania cooperated with the Mongols but remained independent and in the late 14th century formed a personal union with Poland.[230] The Late Middle Ages were marked by difficulties and calamities.[231] Famine, plague, and war devastated the population of Western Europe.[232] The Black Death alone killed approximately 75 to 200 million people between 1347 and 1350.[233] It was one of the deadliest pandemics in human history. Starting in Asia, the disease reached the Mediterranean and Western Europe during the late 1340s,[234] and killed tens of millions of Europeans in six years; between a quarter and a third of the population perished.[235]

Greater Middle East

Before the advent of Islam in the 7th century, the Middle East was dominated by the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, which frequently fought each other for control of several disputed regions.[236] This was also a cultural battle, with Byzantine Christian culture competing against Persian Zoroastrian traditions.[237] The birth of Islam created a new contender that quickly surpassed both of these empires.[238]

Muhammad, the founder of Islam, initiated the early Muslim conquests in the 7th century.[239] He established a new unified polity in Arabia that expanded rapidly under the Rashidun Caliphate and the Umayyad Caliphate, culminating in the establishment of Muslim rule on three continents (Asia, Africa, and Europe) by 750 CE.[240] The subsequent Abbasid Caliphate oversaw the Islamic Golden Age, an era of learning, science, and invention during which philosophy, art, and literature flourished.[241][n] Scholars preserved and synthesized knowledge and skills of ancient Greece and Persia[243] the manufacture of paper from China[244] and the decimal positional numbering system from India.[245] At the same time, they made significant original contributions in various fields, such as Al-Khwarizmi's development of algebra and Avicenna's comprehensive philosophical system.[246] Islamic civilization expanded both by conquest and based on its merchant economy.[247] Merchants brought goods and their Islamic faith to China, India, Southeast Asia, and Africa.[248]

Arab domination of the Middle East ended in the mid-11th century with the arrival of the Seljuk Turks, migrating south from the Turkic homelands.[249] The Seljuks were challenged by Europe during the Crusades, a series of religious wars aimed at rolling back Muslim territory and regaining control of the Holy Land.[250] The Crusades were ultimately unsuccessful and served more to weaken the Byzantine Empire, especially with the sack of Constantinople in 1204.[251] In the early 13th century, a new wave of invaders, the Mongols, swept through the region but were eventually eclipsed by the Turks and the founding of the Ottoman Empire in modern-day Turkey around 1299.[252]

In the 7th century, North Africa saw the extinguishment of Byzantine Africa and the Berber kingdoms in the early Muslim conquests.[253] From the 10th century, the Abbasid Caliphate's African territory was consumed by the Fatimid Caliphate centered on Egypt, who were supplanted by the Ayyubids in the 12th century, and them later by the Mamluks in the 13th century.[254] In the Maghreb and Western Sahara, the Almoravids dominated from the 11th century,[255] until it was subsumed by the Almohad Caliphate in the 12th century.[256] The Almohads' collapse gave rise to the Marinids in Morocco, the Zayyanids in Algeria, and the Hafsids in Tunisia.[257]

The Caucasus was fought over in a series of wars between the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires. However, the two opposing powers became exhausted due to continuous conflict. Hence, the Rashidun Caliphate was able to freely expand into the region during the early Muslim conquests.[258] The Seljuk Turks later subjugated Armenia and Georgia in the 11th century. The Mongols subsequently invaded the Caucasus in the 13th century.[259]

Steppe nomads from Central Asia continued to threaten sedentary societies in the post-classical era, but they also faced incursions from the Arabs and Chinese.[260] China expanded into Central Asia during the Sui dynasty (581–618).[261] The Chinese were confronted by Turkic nomads, who were becoming the most dominant ethnic group in the region.[262] Originally the relationship was largely cooperative but in 630, the Tang dynasty began an offensive against the Turks by capturing areas of the Ordos Desert.[263] In the 8th century, Islam began to penetrate the region and soon became the sole faith of most of the population, though Buddhism remained strong in the east.[264] From the 9th to 13th centuries, Central Asia was divided among several powerful states, including the Samanid,[265] Seljuk,[266] and Khwarazmian Empires. These states were succeeded by the Mongols in the 13th century.[267] In 1370, Timur, a Turkic leader in the Mongol military tradition, conquered most of the region and founded the Timurid Empire.[268] Timur's large empire collapsed soon after his death,[269] but his descendants retained control of a core area in Central Asia and Iran.[270] They oversaw the Timurid Renaissance of art and architecture.[271]

South Asia

After the fall of the Gupta Empire in 550 CE, North India was divided into a complex and fluid network of smaller kingdoms.[272] Early Muslim incursions began in the northwest in 711 CE, when the Arab Umayyad Caliphate conquered much of present-day Pakistan.[240] The Arab military advance was largely halted at that point, but Islam still spread in India, largely due to the influence of Arab merchants along the western coast.[206] The 9th century saw the Tripartite Struggle for control of North India between the Pratihara, Pala, and Rashtrakuta Empires.[273]

Post-classical dynasties in South India included those of the Chalukyas, Hoysalas, and Cholas.[274] Literature, architecture, sculpture, and painting flourished under the patronage of these kings.[275] Some of the other important states that emerged in South India during this time included the Bahmani Sultanate and the Vijayanagara Empire.[276]

Northeast Asia

After a period of relative disunity, China was reunified by the Sui dynasty in 589.[277] Under the succeeding Tang dynasty (618–907), China entered a golden age during which political stability and economic prosperity were accompanied by literary and artistic accomplishment, like the poetry of Li Bai and Du Fu.[278][279] The Sui and Tang instituted the long-lasting imperial examination system, under which administrative positions were open only to those who passed an arduous test on Confucian thought and the Chinese classics.[280] China competed with Tibet (618–842) for control of areas in Inner Asia.[281] However, the Tang dynasty eventually splintered. After half a century of turmoil, the Song dynasty reunified much of China.[282] Pressure from nomadic empires to the north became increasingly urgent.[283] By 1127, northern China had been lost to the Jurchens in the Jin–Song Wars, and the Mongols conquered all of China in 1279.[284] After about a century of Mongol Yuan dynasty rule, the ethnic Chinese reasserted control with the founding of the Ming dynasty in 1368.[283]

In Japan, the imperial lineage was established during the 3rd century CE, and a centralized state developed during the Yamato period (c. 300–710).[285] Buddhism was introduced, and there was an emphasis on the adoption of elements of Chinese culture and Confucianism.[286] The Nara period (710–794) was characterized by the appearance of a nascent literary culture, as well as the development of Buddhist-inspired artwork and architecture.[287] The Heian period (794–1185) saw the peak of imperial power, followed by the rise of militarized clans and the samurai.[288] It was during the Heian period that Murasaki Shikibu penned The Tale of Genji, sometimes considered the world's first novel.[289] From 1185 to 1868, Japan was dominated by powerful regional lords (daimyos) and the military rule of warlords (shoguns) such as the Ashikaga and Tokugawa shogunates.[290] The emperor remained but did not wield significant influence.[291] Meanwhile, the power of merchants grew.[292] An influential art style known as ukiyo-e arose during the Tokugawa years, consisting of woodblock prints that originally depicted famous courtesans.[293]

Post-classical Korea saw the end of the Three Kingdoms era, in which the kingdoms of Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla had competed for hegemony.[294] This period ended when Silla conquered Baekje in 660 and Goguryeo in 668,[295] marking the beginning of the Northern and Southern States period, with Unified Silla in the south and Balhae, a successor state to Goguryeo, in the north.[296] In 892 CE, this arrangement reverted to the Later Three Kingdoms, with Goguryeo[o] emerging as dominant, unifying the entire peninsula by 936.[297] The founding Goryeo dynasty ruled until 1392, succeeded by the Joseon dynasty,[298] which ruled for approximately 500 years.[299]

In Mongolia, Genghis Khan united various Mongol and Turkic tribes under one banner in 1206.[300] The Mongol Empire expanded to comprise all of China and Central Asia, as well as large parts of Russia and the Middle East, to become the largest contiguous empire in history.[301] After Möngke Khan died in 1259,[302] the Mongol Empire was divided into four successor states: the Yuan Dynasty in China, the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia, the Golden Horde in Eastern Europe and Russia, and the Ilkhanate in Iran.[303]

Southeast Asia

The Southeast Asian polity of Funan, which had originated in the 2nd century CE, went into decline in the 6th century as Chinese trade routes shifted away from its ports.[304] It was replaced by the Khmer Empire in 802 CE.[305] The Khmers' capital city, Angkor, was the most extensive city in the world before the industrial age and contained Angkor Wat, the world's largest religious monument.[306] The Sukhothai (mid-13th century CE) and Ayutthaya Kingdoms (1351 CE) were major powers of the Thais, who were influenced by the Khmers.[307]

Starting in the 9th century, the Pagan Kingdom rose to prominence in modern Myanmar.[308] Its collapse brought about political fragmentation that ended with the rise of the Toungoo Empire in the 16th century.[309] Other notable kingdoms of the period include Srivijaya[310] and Lavo (both coming into prominence in the 7th century), Champa[311] and Hariphunchai (both about 750),[312] Đại Việt (968),[313] Lan Na (13th century),[314] Majapahit (1293),[315] Lan Xang (1353),[316] and Ava (1365).[317] Hinduism and Buddhism had been spreading in Southeast Asia since the 1st century CE when, beginning in the 13th century, Islam arrived and made its way to regions such as present-day Indonesia.[318] This period also saw the emergence of the Malay states, including Brunei and Malacca.[319] In the Philippines, several polities were formed such as Tondo, Cebu, and Butuan.[320]

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa was home to many different civilizations. In Nubia, the Kingdom of Kush was succeeded by the Christian kingdoms of Makuria, Alodia, and Nobatia. In the 7th century, Makuria conquered Nobatia to become the dominant power in the region and resisted Muslim expansion.[321] They later entered a severe decline following civil war and Arab migrations to the Sudan and had disintegrated by the 15th century, giving rise to the Funj Sultanate.[322]

In the Horn of Africa, Islam spread among the Somalis, while the Kingdom of Aksum declined from the 7th century following Muslim dominance over the Red Sea trade, and collapsed in the 10th century.[323] The Zagwe dynasty emerged in the 12th century and contested hegemony with the Sultanate of Shewa and the powerful Kingdom of Damot.[324]: 423, 431 In the 13th century, the Zagwe were overthrown by the Solomonic dynasty of the Ethiopian Empire, while Shewa gave way to the Walashma dynasty of the Sultanate of Ifat.[325]: 123–134, 140 Ethiopia emerged victorious against Ifat and occupied the Muslim states.[326]: 143 The Ajuran Sultanate rose on the Horn's east coast to dominate the Indian Ocean trade.[327] Ifat was succeeded by the Adal Sultanate who reconquered much of the Muslim lands.[326]: 149

In the West African Sahel region, the Ghana Empire grew from the 2nd to 8th centuries, while the Gao Empire was established in the 7th century.[328][329] The Almoravid capture of Aoudaghost precipitated Ghana's conversion to Islam in the 11th century,[330] and climatic changes led to Ghana's conquest by its vassal Sosso in the 13th century.[331] Sosso was quickly overthrown by the Mali Empire, which conquered Gao and dominated the trans-Saharan trade.[332] The Mossi Kingdoms were established to its south.[333] To the east, the Kanem–Bornu Empire ruled from the 6th century and projected power over the Hausa Kingdoms.[334][335] The 15th century saw the crumbling of the Mali Empire, with the dominant power in the region becoming the Songhai Empire centered on Gao.[336]

In the forest regions of West Africa, various kingdoms and empires flourished, such as the Yoruba empires of Ife and Oyo,[337] the Igbo Kingdom of Nri,[338] the Edo Kingdom of Benin (famous for its art),[339] the Dagomba Kingdom of Dagbon,[340] and the Akan kingdom of Bonoman.[341] In the 15th century, the Portuguese came into contact with the region, which saw the start of the Atlantic slave trade.

In the Congo Basin, there were three main confederations of states by the 13th century: the Seven Kingdoms, Mpemba, and one led by Vungu.[342]: 24–25 In the 14th century, the Kingdom of Kongo emerged and dominated the region.[342] Further east, the Luba Empire was founded in the Upemba Depression in the 15th century.[343] In the northern Great Lakes region, the Empire of Kitara rose around the 11th century, famed for its total lack of written record. Kitara collapsed in the 15th century following the Luo migrations.[344]

Along the Swahili coast, city-states thrived off of the Indian Ocean trade and gradually Islamized, giving rise to the Kilwa Sultanate in the 10th century.[345][346] Madagascar was settled by Austronesian peoples between the 5th and 7th centuries, as societies organized at the behest of hasina.[347]: 43, 52–53 In Southern Africa, early kingdoms included Mapela and Mapungubwe,[348] followed by the Kingdom of Zimbabwe in the 13th century and the Mutapa Empire in the 15th century.[349]

Oceania

The Polynesians, descendants of the Lapita peoples, colonized vast reaches of Remote Oceania beginning around 1000 CE.[351][p] Their voyages resulted in the colonization of hundreds of islands including the Marquesas, Hawaii, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), and New Zealand.[353]

The Tuʻi Tonga Empire was founded in the 10th century CE and expanded between 1250 and 1500.[354] Tongan culture, language, and hegemony spread widely throughout eastern Melanesia, Micronesia, and central Polynesia during this period.[355] They influenced east 'Uvea, Rotuma, Futuna, Samoa, and Niue, as well as specific islands and parts of Micronesia, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia.[356] In Northern Australia, there is evidence that Aboriginal Australians regularly traded with Makassan trepangers from Indonesia before the arrival of Europeans.[357] In Aboriginal societies, leadership was based on achievement while the social structure of Polynesian societies was characterized by hereditary chiefdoms.[358]

Americas

In North America, this period saw the rise of the Mississippian culture in the modern-day United States c. 950 CE,[359] marked by the extensive 11th-century urban complex at Cahokia.[360] The Ancestral Puebloans and their predecessors (9th–13th centuries) built extensive permanent settlements, including stone structures that remained the largest buildings in North America until the 19th century.[361]

In Mesoamerica, the Teotihuacan civilization fell and the classic Maya collapse occurred.[362] The Aztec Empire came to dominate much of Mesoamerica in the 14th and 15th centuries.[363]

In South America, the 15th century saw the rise of the Inca.[211] The Inca Empire, with its capital at Cusco, spanned the entire Andes, making it the most extensive pre-Columbian civilization.[364] The Inca were prosperous and advanced, known for an excellent road system and elegant stonework.[365]

Early modern period

The early modern period is the era following the European Middle Ages until 1789 or 1800.[q] A common break with the medieval period is placed between 1450 and 1500 which includes a number of significant events: the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire, the spread of printing and European voyages of discovery to America and along the African coast.[367] The nature of warfare evolved as the size and organization of military forces on land and sea increased, alongside the wider propagation of gunpowder.[368] The early modern period is significant for the start of proto-globalization,[369] increaslingly centralized bureaucratic states[370] and early forms of capitalism.[366] European powers also began colonizing large parts of the world through maritime empires: first the Portuguese and Spanish Empires, then the French, English, and Dutch Empires.[371] Historians still debate the causes of Europe's rise, which is known as the Great Divergence.[372]

Capitalist economies emerged, initially in the northern Italian republics and some Asian port cities.[373] European states practiced mercantilism by implementing one-sided trade policies designed to benefit the mother country at the expense of its colonies.[374] Starting at the end of the 15th century, the Portuguese established trading posts across Africa, Asia, and Brazil, for commodities like gold and spices while also practicing slavery.[375] In the 17th century, private chartered companies were established, such as the English East India Company in 1600 – often described as the first multinational corporation – and the Dutch East India Company in 1602.[376] Meanwhile, in much of the European sphere, serfdom declined and eventually disappeared while the power of the Catholic Church waned.[377]

The Age of Discovery was the first period in which the Old World engaged in substantial cultural, material, and biological exchange with the New World. It began in the late 15th century, when Portugal and Castile sent the first exploratory voyages to the Americas, where Christopher Columbus first arrived in 1492. Global integration continued as European colonization of the Americas initiated the Columbian exchange: the exchange of plants, animals, foods, human populations (including slaves), communicable diseases, and culture between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres.[378] It was one of history's most important global events, involving ecology and agriculture.[379] New crops brought from the Americas by 16th-century European seafarers substantially contributed to world population growth.[380]

Europe

The early modern period in Europe was an era of intense intellectual ferment. The Renaissance – the "rebirth" of classical culture, beginning in Italy in the 14th century and extending into the 16th[r] – comprised the rediscovery of the classical world's cultural, scientific, and technological achievements, and the economic and social rise of Europe.[382] This period is also celebrated for its artistic and literary attainments.[383] Petrarch's poetry, Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron, and the paintings and sculptures of Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer, as part of the Northern Renaissance, are some of the great works of the age.[383] After the Renaissance came the Reformation, an anti-clerical theological and social movement started in Germany by Martin Luther that resulted in the creation of Protestant Christianity.[384]

The Renaissance also engendered a culture of inquisitiveness which ultimately led to humanism[385] and the Scientific Revolution, an effort to understand the natural world through direct observation and experiment.[386] The success of the new scientific techniques inspired attempts to apply them to political and social affairs, known as the Enlightenment, by thinkers such as John Locke and Immanuel Kant.[387] This development was accompanied by secularization as a continued decline of the influence of religious beliefs and authorities in the public and private spheres.[388] Johannes Gutenberg's invention of movable type printing in 1440[s] helped spread the ideas of the new intellectual movements.[390]

In addition to changes wrought by incipient capitalism and colonialism, early modern Europeans experienced an increase in the power of the state.[391] Absolute monarchs in France, Russia, the Habsburg lands, and Prussia produced powerful centralized states, with strong armies and efficient bureaucracies, all under the control of the king.[392] In Russia, Ivan the Terrible was crowned in 1547 as the first tsar of Russia, and by annexing the Turkic khanates in the east, transformed Russia into a regional power, eventually replacing the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a major power in Eastern Europe.[393] The countries of Western Europe, while expanding prodigiously through technological advances and colonial conquest, competed with each other economically and militarily in a state of almost constant war.[394] Wars of particular note included the Thirty Years' War, the War of the Spanish Succession, the Seven Years' War, and the French Revolutionary Wars.[395] The French Revolution, starting in 1789, laid the groundwork of liberal democracy by overthrowing monarchy. It led to the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte and the subsequent Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century.[396]

Greater Middle East

The Ottoman Empire quickly came to dominate the Middle East after conquering Constantinople in 1453, which marked the end of the Byzantine Empire.[397] Persia came under the rule of the Safavids in 1501,[398] succeeded by the Afshars in 1736, the Zands in 1751, and the Qajars in 1794.[399] The Safavids established Shia Islam as Persia's official religion, thus giving Persia a separate identity from its Sunni neighbors.[400] Along with the Mughals in India, the Ottomans and Safavids are known as the gunpowder empires because of their early adoption of firearms.[401] Throughout the 16th century the Ottomans conquered all of North Africa save for Morocco, which came under the rule of the Saadi dynasty at the same time, and then the Alawi dynasty in the 17th century.[402][403][404] At the end of the 18th century, the Russian Empire began its conquest of the Caucasus.[405] The Uzbeks replaced the Timurids as the preeminent power in Central Asia.[406]

South Asia

In the Indian subcontinent, the Mughal Empire was established under Babur in 1526 and lasted for two centuries.[407] Starting in the northwest, it brought the entire subcontinent under Muslim rule by the late 17th century,[408] except for the southernmost Indian provinces, which remained independent.[409] To resist the Muslim rulers, the Hindu Maratha Empire was founded by Shivaji on the western coast in 1674.[410] The Marathas gradually gained territory from the Mughals over several decades, particularly in the Mughal–Maratha Wars (1680–1707).[411]

Sikhism developed at the end of the 15th century from the spiritual teachings of ten gurus.[412] In 1799, Ranjit Singh established the Sikh Empire in the Punjab.[413]

Northeast Asia

In 1644, the Ming were supplanted by the Qing,[414] the last Chinese imperial dynasty, which ruled until 1912.[415] Japan experienced its Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568–1600), followed by the Edo period (1600–1868).[416] The Korean Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) ruled throughout this period, repelling invasions from Japan and China in the 16th and 17th centuries.[417] Expanded maritime trade with Europe significantly affected China and Japan during this period, particularly through the Portuguese in Macau and the Dutch in Nagasaki.[418] However, China and Japan later pursued isolationist policies[t] designed to eliminate foreign influences.[419]

Southeast Asia

In 1511, the Portuguese overthrew the Malacca Sultanate in present-day Malaysia and Indonesian Sumatra.[420] The Portuguese held this important trading territory (and the valuable associated navigational strait) until overthrown by the Dutch in 1641.[376] The Johor Sultanate, centered on the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, became the dominant trading power in the region.[421]

European colonization expanded with the Dutch in Indonesia, the Portuguese in Timor, and the Spanish in the Philippines.[422]

Sub-Saharan Africa

In the Horn of Africa, there was the Oromo expansion in the 16th century, which weakened Ethiopia and caused Adal's collapse. Ajuran was succeeded by the Geledi Sultanate.[423] In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ethiopia rapidly expanded.[424]

In West Africa, the Songhai Empire fell to Moroccan invasion in the late 16th century.[425] They were succeeded by the Bamana Empire. The Fula jihads beginning in the 18th century led to the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate, the Massina Empire, and the Tukulor Empire.[426][427][428] In the forest regions, the Asante Empire was established in present-day Ghana.[429] Between 1515 and 1800, 8 million Africans were exported in the Atlantic slave trade.[430]

In the Congo Basin, Kongo fought three wars against the Portuguese who had begun colonizing Angola, ending in the conquest of Ndongo in the 17th century.[431] Further east, the Lunda Empire rose to dominate the region.[432] It fell to the Chokwe in the 19th century.[433] In the northern Great Lakes, there were the kingdoms of Bunyoro-Kitara, Buganda, and Rwanda among others.[434]

Kilwa was conquered by the Portuguese in the 16th century as they began colonizing Mozambique. They were defeated by the Omani Empire who took control of the Swahili coast.[435] In Madagascar the 16th century onward saw the emergence of Imerina, the Betsileo kingdoms, and the Sakalava empire;[436] Imerina conquered most of the island in the 19th century.[437] In the Zambezi Basin Mutapa was followed by the Rozvi Empire,[438] with Maravi around Lake Malawi to its north.[439] Mthwakazi succeeded Rozvi.[440] Further south, the Dutch began colonizing South Africa in the 16th century, who lost it to the British.[441] In the 19th century Dutch settlers formed various Boer Republics, while the Mfecane ravaged the region and led to the establishment of various African kingdoms.[442]

Oceania

The Pacific Islands of Oceania were also affected by European contact, starting with the circumnavigational voyage of Ferdinand Magellan (1519–1522),[u] who landed in the Marianas and other islands.[443] Abel Tasman (1642–1644) sailed to present-day Australia, New Zealand, and nearby islands.[444] James Cook (1768–1779) made the first recorded European contact with Hawaii.[445] In 1788, Britain founded its first Australian colony.[446]

Americas

Several European powers colonized the Americas, largely displacing the native populations and conquering the advanced civilizations of the Aztecs and Inca.[447] Diseases introduced by Europeans devastated American societies, killing 60–90 million people by 1600 and reducing the population by 90–95%.[448] In some cases, colonial policies included the deliberate genocide of indigenous peoples.[449] Spain, Portugal, Britain, and France all made extensive territorial claims, and undertook large-scale settlement, including the importation of large numbers of African slaves.[450] One side-effect of the slave trade was cultural exchange through which various African traditions found their way to the Americas, including cuisine, music, and dance.[451][v] Portugal claimed Brazil, while Spain seized the rest of South America, Mesoamerica, and southern North America.[452] The Spanish mined and exported prodigious amounts of gold and silver, leading to a surge in inflation known as the Price Revolution in the 16th and 17th centuries in Western Europe.[453]

In North America, Britain colonized the east coast while France settled the central region.[454] Russia made incursions into the northwest coast of North America, with its first colony in present-day Alaska in 1784,[455] and the outpost of Fort Ross in present-day California in 1812.[456] France lost its North American territory to England and Spain after the Seven Years' War (1756–1763).[457] Britain's Thirteen Colonies declared independence as the United States in 1776, ratified by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, ending the American Revolutionary War.[458] In 1791, African slaves launched a successful rebellion in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. France won back its continental claims from Spain in 1800, but sold them to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.[459]

Modern era

Long nineteenth century

The long nineteenth century traditionally starts with the French Revolution in 1789,[w] and lasts until the outbreak of World War I in 1914.[462] It saw the global spread of the Industrial Revolution, the greatest transformation of the world economy since the Neolithic Revolution.[463] The Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain around 1770 and used new modes of production—the factory, mass production, and mechanization—to manufacture a wide array of goods faster while using less labor than previously required.[464]

Industrialization raised the global standard of living but caused upheaval as factory owners and workers clashed over wages and working conditions.[465] Along with industrialization came modern globalization, the increasing interconnection of world regions in the economic, political, and cultural spheres.[466] Globalization began in the early 19th century and was enabled by improved transportation technologies such as railroads and steamships.[467]

European empires lost territories in Latin America, which won independence by the 1820s through military campaigns,[468] but expanded elsewhere as their industrial economies gave them an advantage over the rest of the world.[469] Britain gained control of the Indian subcontinent, Burma, Malaya, North Borneo, Hong Kong, and Aden; the French took Indochina; and the Dutch cemented their rule over Indonesia.[470] The British also colonized Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa with large numbers of British colonists emigrating to these colonies.[471]

Russia colonized large pre-agricultural areas of Siberia.[472] The United States completed its westward expansion, establishing control over the territory from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast.[473]

In the late 19th century to early 20th century, the European powers, driven by the Second Industrial Revolution, rapidly conquered and colonized almost the entirety of Africa.[474] Only Ethiopia and Liberia remained independent.[475] Imperial rule in Africa involved many atrocities such as those in the Congo Free State and the Herero and Nama genocide.[476]

Within Europe, economic and military competition fostered the creation and consolidation of nation-states, and other ethno-cultural communities began to identify themselves as distinctive nations with aspirations for their own cultural and political autonomy.[477] This nationalism became important to peoples across the world in the 19th and 20th centuries.[478] In the first wave of democratization, between 1828 and 1926, democratic institutions were established in 33 countries worldwide.[479]

Most of the world abolished slavery and serfdom in the 19th century.[480] Over several decades, beginning in the late 19th century and continuing throughout the 20th,[481] in many countries the women's suffrage movement won women the right to vote,[482] and women began to enjoy greater access to education and to professions beyond domestic employment.[483]

In response to encroachment by European powers, several countries undertook programs of industrialization and political reform along Western lines.[484] The Meiji Restoration in Japan led to the establishment of a colonial empire, while the tanzimat reforms in the Ottoman Empire did little to slow the Ottoman decline.[485] China achieved some success with its Self-Strengthening Movement but was devastated by the Taiping Rebellion, history's bloodiest civil war, which between 1850 and 1864 killed 20–30 million people.[486]

By the end of the century, the United States became the world's largest economy.[487] During the Second Industrial Revolution, new technological advances, involving electric power, the internal combustion engine, and assembly-line manufacturing, further increased productivity.[488] Technological innovations also provided new avenues for artistic expression through the media of photography, sound recording, and film.[489]

Meanwhile, industrial pollution and environmental degradation accelerated drastically.[490] Balloon flight had been invented in the late 18th century, but it was only at the beginning of the 20th century that powered aircraft were developed.[491]

The 20th century opened with Europe at an apex of wealth and power.[492] Much of the world was under its direct colonial control or its indirect influence through heavily Europeanized nations like the United States and Japan.[493] As the century unfolded, however, the global system dominated by rival powers experienced severe strains and ultimately yielded to a more fluid structure of independent nation states.[494]

World wars

This transformation was catalyzed by wars of unparalleled scope and devastation. World War I was a global conflict from 1914 to 1918 between the Allies, led by France, Russia, and the United Kingdom, and the Central Powers, led by Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria. It had an estimated death toll ranging from 10 to 22.5 million and resulted in the collapse of four empires – the Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman, and Russian Empires.[495] Its new emphasis on industrial technology had made traditional military tactics obsolete.[496]

The Armenian, Assyrian, and Greek genocides saw the systematic destruction, mass murder, and expulsion of those populations in the Ottoman Empire.[497] From 1918 to 1920, the Spanish flu caused the deaths of at least 25 million people.[498]

In the war's aftermath a League of Nations was formed in the hope of averting future international conflicts;[499] and powerful ideologies rose to prominence. The Russian Revolution of 1917 created the first communist state,[500] while the 1920s and 1930s saw fascist political parties gain control in Italy and Germany.[501][x] The Soviet Union, during Joseph Stalin's rule from 1924 to 1953, committed countless atrocities against its own people, including mass purges, forced labor camps, and widespread famine caused by state policies.[503]

Ongoing national rivalries, exacerbated by the economic turmoil of the Great Depression, helped precipitate World War II.[504] In that war, the vast majority of the world's countries, including all the great powers, fought as part of two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis. The leading Axis powers were Germany, Japan, and Italy;[505] while the United Kingdom, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the Republic of China were the "Big Four" Allied powers.[506]

The militaristic governments of Germany and Japan pursued an ultimately doomed course of imperialist expansionism. In the course of doing so, Germany orchestrated the genocide of six million Jews in the Holocaust, and of millions of non-Jews across German-occupied Europe,[507] while Japan murdered millions of Chinese.[508] The war also saw the introduction and use of nuclear weapons, which brought unprecedented destruction and ultimately led to Japan's surrender.[509] Estimates of the war's total casualties range from 55 to 80 million.[510]

Contemporary history

When World War II ended in 1945, the United Nations was founded in the hope of preventing future wars,[511] as the League of Nations had been formed following World War I.[512] The United Nations championed the human rights movement, in 1948 adopting a Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[513] Several European countries formed what would evolve into a 27-member-state economic and political community, the European Union.[514]

World War II had opened the way for the advance of communism into Eastern and Central Europe, China, North Korea, North Vietnam, and Cuba.[515] To contain this advance, the United States established a global network of alliances.[516] The largest, NATO, was established in 1949 and eventually grew to include 32 member states.[517] In response, in 1955 the Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies formed the Warsaw Pact mutual-defense treaty.[518]

The United States and the Soviet Union emerged as the primary global powers in the aftermath of World War II.[519] Both nations harbored deep suspicions and fears about the global spread of the other's political-economic system — capitalism for the United States and communism for the Soviet Union.[520] This mutual distrust sparked the Cold War, a 45-year stand-off and arms race between the two nations and their allies.[521]

With the development of nuclear weapons during World War II and their subsequent proliferation, all of humanity was put at risk of nuclear war between the two superpowers, as demonstrated by many incidents, most prominently the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.[522] Such war being viewed as impractical, the superpowers instead waged proxy wars in non-nuclear-armed Third World countries.[523] The Cold War ended peacefully in 1991 after the Soviet Union collapsed,[524] partly due to its inability to compete economically with the United States and Western Europe.[525]

Cold War preparations to deter or fight a third world war accelerated advances in technologies that, though conceptualized before World War II, had been implemented for that war's exigencies, such as jet aircraft,[526] rocketry,[527] and computers.[528] In the decades after World War II, these advances led to jet travel;[526] artificial satellites with innumerable applications,[529] including GPS;[530] and the Internet,[529] which in the 1990s began to gain traction as a form of communication.[531] These inventions revolutionized the movement of people, ideas, and information.[532]

The second half of the 20th century also saw groundbreaking scientific and technological developments such as the discovery of the structure of DNA[533] and DNA sequencing,[534] the worldwide eradication of smallpox,[535] the Green Revolution in agriculture,[536] the discovery of plate tectonics,[537] the moon landings,[538] crewed and uncrewed exploration of space,[539] advances in energy technologies,[540] and foundational discoveries in physics phenomena ranging from the smallest entities (particle physics) to the greatest (physical cosmology).[537]

These technical innovations had far-reaching effects.[541] During the 20th century the world's population quadrupled to six billion, while world economic output increased by a factor of 20.[542] Toward the end of the 20th century, the rate of population growth started to decline, in part because of increased awareness of family planning and better access to contraceptives.[543] Parts of the world now have sub-replacement fertility rates.[544]

Public health measures and advances in medical science contributed to a sharp increase in global life expectancy at birth from about 31 years in 1900 to over 66 years in 2000.[545][y] In 1820, 75% of humanity lived on less than one dollar a day, while in 2001 only about 20% did.[547] At the same time, economic inequality increased both within individual countries and between rich and poor countries.[548] The importance of public education had already begun to increase in the 18th and 19th centuries[z] but it was not until the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century that compulsory free education was provided to most children worldwide.[550][aa]

In China, the Maoist government implemented industrialization and collectivization policies as part of the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962), leading to the starvation deaths (1959–1961) of 30–40 million people.[552] After these policies were rescinded, China entered a period of economic liberalization and rapid growth, with the economy expanding by 6.6% per year from 1978 to 2003.[553]

In the postwar decades, in a process of decolonization, the African, Asian, and Oceanian colonies of European empires won their formal independence.[554] Postcolonial states in Africa struggled to grow their economies, facing structural barriers such as reliance on the export of commodities rather than manufactured goods.[555] Sub-Saharan Africa was the world region hit hardest by the HIV/AIDS pandemic of the late 20th century.[556] Moreover, Africa experienced high levels of violence, as in the Second Congo War (1998–2003), the deadliest conflict since World War II.[557]

The Near East experienced numerous conflicts, including the Iran-Iraq War, the first and second Gulf wars, and the Syrian Civil War, as well as tensions and conflicts between Israel and Palestine.[558] Development efforts in Latin America were hindered by over-reliance on commodity exports[559] and by political instability, some of it caused by United States involvement in regime change in Latin America.[560]

The early 21st century was marked by growing economic globalization and integration,[561] which brought both benefits and risks to interlinked economies, as exemplified by the Great Recession of the late 2000s and early 2010s.[562] Communications expanded, with smartphones and social media becoming ubiquitous worldwide by the mid-2010s. By the early 2020s, artificial intelligence systems improved to the point of outperforming humans at many circumscribed tasks.[563]

The influence of religion continued to decline in many Western countries, while some parts of the Muslim world saw the rise of fundamentalist movements.[564] In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic substantially disrupted global trading, caused recessions in the global economy, and spurred cultural paradigm shifts.[565]

Concerns grew as existential threats from environmental degradation and global warming became increasingly evident,[566] while mitigation efforts, including a shift to sustainable energy, made gradual progress.[567]

Academic research

The study of human history has a long tradition and early precursors were already practiced in the ancient period as attempts to provide comprehensive accounts of the history of the world.[ab] Most research before the 20th century focused on histories of individual communities and societies after the prehistoric period. This changed in the late 20th century, when attempts to integrate the diverse narratives into a common context reaching back to the emergence of the first humans became a central research topic.[569] This transition to a widened perspective was accompanied by questioning Eurocentrism and the Western-focused perspective that had previously dominated academic history.[570]

Like in other historical disciplines, the methodology of analyzing textual sources to construct narratives and interpretations of past events plays a central role in the study of human history. The scope of its topic poses the unique challenge of synthesizing a coherent and comprehensive narrative spanning different cultures, regions, and time periods while taking diverse individual perspectives into account. This is also reflected in its interdisciplinary approach by integrating insights from fields belonging to the humanities and the social, biological, and physical sciences, such as other historical disciplines, archaeology, anthropology, linguistics, genetics, paleontology, and geology. The interdisciplinary approach is of particular importance to the study of human history before the invention of writing.[571]

Periodization

To provide an accessible overview, historians divide human history into different periods organized around key themes, events, or developments that have shaped human societies over time. The number of periods and their time frames depend on the chosen topics, and the transitions between periods are often more fluid than static periodization schemes suggest.[572]

A traditionally influential periodization in European scholarship distinguishes between the ancient, medieval, and modern periods[573] organized around historical events responsible for major shifts in political, economic, and cultural structures to mark the transitions between the periods: first the fall of the Western Roman Empire and later the emergence of the Renaissance.[574] Another periodization divides human history into three periods based on the way humans engage with nature to produce goods. The first transition happened with the emergence of agriculture and husbandry to replace hunting and gathering as the main means of food production. The Industrial Revolution constitutes the second transition.[575] A further approach uses the relations between societies to divide the history of the world into the periods of Middle Eastern dominance before 500 BCE, Eurasian cultural balance until 1500 CE, and Western dominance afterward.[576] The invention of writing is often used to demark prehistory from the ancient period while another approach divides early history based on the type of tools used in the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages.[577] Historians focusing on religion and culture identify the Axial Age as a key turning point that laid the spiritual and philosophical foundations of many of the world's major civilizations. Some historians draw on elements from different approaches to arrive at a more nuanced periodization.[578]

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ This date comes from the 2015 discovery of stone tools at the Lomekwi site in Kenya.[3] Some paleontologists propose an earlier date of 3.39 million years ago based on bones found with butchery marks on them in Dikika, Ethiopia,[4] while others dispute both the Dikika and Lomekwi findings.[5]

- ^ the African variant is sometimes called H. ergaster

- ^ Or perhaps earlier; the 2018 discovery of stone tools from 2.1 million years ago in Shangchen, China predates the earliest known H. erectus fossils.[12]

- ^ Some authors suggest a later date at around 200,000 years ago.[19]

- ^ The term Homo rhodesiensis is also sometimes used.

- ^ These dates come from a 2018 study of an upper jawbone from Misliya Cave, Israel.[29] Researchers studying a fossil skull from Apidima Cave, Greece in 2019 proposed an earlier date of 210,000 years ago.[30] The Apidima Cave study has been challenged by other scholars.[31]

- ^ Other scholars argue in favor of a northern dispersal of humans through Central Asia into China, or a multiple dispersal model with several different routes of migration.[33]

- ^ This occurred during the African humid period, when the Sahara was much wetter than it is today.[47]

- ^ This is the traditional date for the founding of the Xia dynasty and has not been confirmed by archaeology.[69] Chinese civilization had its origins in the earlier Yangshao and Longshan cultures (4000–2000 BCE),[70] but the Shang is the first dynasty that can be archeologically verified (1750 BCE).[71]

- ^ Various forms of proto-writing existed earlier but they did not constitute fully developed writing system.[85]

- ^ Cuneiform texts were written by using a blunt reed as a stylus to draw symbols upon clay tablets.[87]

- ^ The Vedas contain the earliest references to India's caste system, which divided society into four hereditary classes: priests, warriors, farmers and traders, and laborers.[104]

- ^ The exact dates are disputed and some periodizations use 1450 as the end point.[199]

- ^ For example, the folktales One Thousand and One Nights were written in this period.[242]

- ^ Goguryeo was called Taebong at that time and eventually named Goryeo.

- ^ They traveled the open ocean in double-hulled canoes up to 37 metres (121 ft) long, each canoe carrying as many as 50 people and their livestock.[352]

- ^ The time span varies depending on the type of history studied: literary studies can define it as short as about 1500–1700 while some general historians extend its span from 1300–1800.[366]

- ^ Some scholars date the period later, to the 15th and 16th centuries.[381]

- ^ The Chinese invented movable type centuries earlier, but it was better suited to the alphabetical writing systems of European languages.[389]

- ^ They are known as haijin in China and sakoku in Japan.

- ^ Magellan died in 1521. The voyage was completed by Spanish navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano in 1522.[443]

- ^ In Brazil, this influence resulted in the development of Capoeira.[451]

- ^ Some historians use a different periodization, saying that it began as early as 1750[460] or as late as 1800.[461]