Hattusa

Hattuşaş (Turkish) | |

The Lion Gate in the south-west | |

| Location | Near Boğazkale, Çorum Province, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Region | Anatolia |

| Coordinates | 40°01′11″N 34°36′55″E / 40.01972°N 34.61528°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | 6th millennium BC |

| Abandoned | c. 1200 BC |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

| Cultures | Hittite |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

| Official name | Hattusha: the Hittite Capital |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 377 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

| Area | 268.46 ha |

Hattusa, also Hattuşa, Ḫattuša, Hattusas, or Hattusha, was the capital of the Hittite Empire in the late Bronze Age during two distinct periods. Its ruins lie near modern Boğazkale, Turkey, (originally Boğazköy) within the great loop of the Kızılırmak River (Hittite: Marashantiya; Greek: Halys).

Charles Texier brought attention to the ruins after his visit in 1834. Over the following century, sporadic exploration occurred, involving different archaeologists. In the 20th century, the German Oriental Society and the German Archaeological Institute conducted systematic excavations, which continue to this day.[1] Hattusa was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Site list in 1986.

History

[edit]

The earliest traces of settlement on the site are from the sixth millennium BC during the Chalcolithic period. Toward the end of the 3rd Millennium BC the Hattian people established a settlement on locations that had been occupied even earlier and referred to the site as Hattush.[2] In the 19th and 18th centuries BC, merchants from Assyria, centered at Kanesh (Neša) (modern Kültepe) established a trading post there, setting up in their own separate quarter of the lower city.[3]

A carbonized layer apparent in excavations attests to the burning and ruin of the city of Hattusa around 1700 BC. The responsible party appears to have been King Anitta from Kussara, who took credit for the act and erected an inscribed curse for good measure:

"Whoever after me becomes king resettles Hattusas, let the Stormgod of the Sky strike him!"[4]

though in fact the city was rebuilt afterward, possibly by a son of Anitta.[5][6]

In the first half of the 2nd Millennium BC around the year 1650 BC the Hittite king Labarna moved the capital from Neša to Hattusa and took the name of Hattusili, the "one/man from Hattusa".[7][8] After the Kaskians arrived to the kingdom's north, they twice attacked the city and under king Tudhaliya I, the Hittites moved the capital north to Sapinuwa. Under Muwatalli II, they moved south to Tarhuntassa but the king assigned his younger brother, the future Hattusili III as governor over Hattusa.[9] In the mid-13th century BC Hittite ruler Mursili III returned the seat to Hattusa, where the capital remained until the end of the Hittite kingdom in the 12th century BC (KBo 21.15 i 11–12).[10]

At its peak, the city covered 1.8 km2 (440 acres) and comprised an inner and outer portion, both surrounded by a massive and still visible course of walls erected during the reign of Suppiluliuma I (c. 1344–1322 BC (short chronology)). The inner city covered an area of some 0.8 km2 (200 acres) and was occupied by a citadel with large administrative buildings and temples. The royal residence, or acropolis, was built on a high ridge now known as Büyükkale (Great Fortress).[11] The city displayed over 6 km (3.7 mi) of walls, with inner and outer skins around 3 m (9.8 ft) of thick and 2 m (6 ft 7 in) of space between them, adding 8 m (26 ft) of the total thickness.[12]

To the south lay an outer city of about 1 km2 (250 acres), with elaborate gateways decorated with reliefs showing warriors, lions, and sphinxes. Four temples were located here, each set around a porticoed courtyard, together with secular buildings and residential structures. Outside the walls are cemeteries, most of which contain cremation burials. Modern estimates put the population of the city around 10,000;[13] in the early period, the inner city housed a third of that number. The dwelling houses that were built with timber and mud bricks have vanished from the site, leaving only the stone-built walls of temples and palaces.

The city was destroyed, together with the Hittite state itself, around 1200 BC, as part of the Bronze Age collapse. Excavations suggest that Hattusa was gradually abandoned over a period of several decades as the Hittite empire disintegrated.[14] It has been suggested that a regional drought occurred at that time.[15] Still, signs of final destruction by fire have been noted.[16] The site was subsequently abandoned until 800 BC, when a modest Phrygian settlement appeared in the area.

Archaeology

[edit]

In 1833, the French archaeologist Félix Marie Charles Texier (1802–1871) was sent on an exploratory mission to Turkey, where in 1834 he discovered monumental ruins near the town of Boğazköy.[17] Texier made topographical measurements, produced illustrations, and composed a preliminary site plan.[18] The site was subsequently visited by a number of European travelers and explorers, most notably the German geographer Heinrich Barth in 1858.[19] Georges Perrot excavated at the site in 1861 and at the nearby site of Yazılıkaya.[20] Perrot was the first to suggest, in 1886, that Boğazköy was the Hittite capital of Hattusa.[21] In 1882 German engineer Carl Humann completed a full plan of the site.

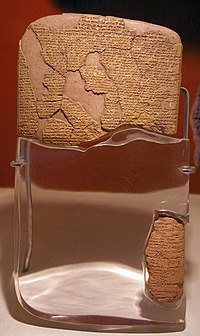

Ernest Chantre opened some trial trenches at the village then called Boğazköy, in 1893–94, with excavations being cut short by a cholera outbreak. Significantly Chantre discovered some fragments of clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform. The fragments contain text in both the Akkadian language and what later was determined to be the Hittite language.[22][23] Between 1901 and 1905 Waldemar Belck visited the site several times, finding a number of tablets.

In 1905 Hugo Winckler conducted some soundings at Boğazköy on behalf of the German Oriental Society (DOG), finding 35 more cuneiform tablet fragments at the site of the royal fortress, Büyükkale.[24] Winckler began actual excavations in 1906, focusing mainly on the royal fortress area. Thousands of tablets were recovered, most in the then unreadable Hittite language. The few Akkadian texts firmly identified the site as Hattusa.[25] Winckler returned in 1907 (with Otto Puchstein, Heinrich Kohl, Ludwig Curtius and Daniel Krencker), and briefly in 1911 and 1912 (with Theodore Makridi). Work stopped with the outbreak of WWI.[26][27] Tablets from these excavations were published in two series Keilschrifttexte aus Boghazkoi (KB0) and Keilschrift urkunden aus Boghazköi (KUB). Work resumed in 1931 under prehistorian Kurt Bittel with establishing stratigraphy as the major focus. The work was under the auspices of the DOG and German Archaeological Institute (Deutsches Archäologisches Institut) and lasted 9 seasons until being suspended due to the outbreak of WWII in 1939.[28][29] Excavation resumed in 1952 under Bittel with Peter Neve replacing as field director in 1963 and as director in 1978, continuing until 1993.[30] The focus was on the Upper City area. Publication of tablets was resumed in the KUB and KBo.[31][32] In 1994 Jürgen Seeher assumed control of the excavation, leading there until 2005, with the focus on the Büyükkaya and non-monumental areas including economic and residential spaces.[33] From 2006 on, while some archaeology continued under new director Andreas Schachner, activities have been more focused toward restoration and preparation for tourist operations.[34][35][36]

During the 1986 excavations a large (35 × 24 cm, 5 kg in weight, with 2 attached chains) inscribed metal tablet was discovered 35 meters west of the Sphinx Gate. The tablet, from the 13th century BC, contained a treaty between Hittite Tudḫaliya IV and Kurunta, King of Tarḫuntašša. It is held at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara.[37][38] During 1991 repair work at the site a Mycenae bronze sword was found on the western slope. It was inscribed, in Akkadian, "As Duthaliya the Great King shattered the Assuwa-Country he dedicated these swords to the Storm-God, his lord".[39][40] Another significant find during the 1990-91 excavation season in the "Westbau" building of the upper city, was 3400 sealed bullae and clay lumps dating from the 2nd half of the 13th century BC. They were primarily associated with land documents.[41]

Cuneiform royal archives

[edit]

Forty mercantile documents written in the Old Assyrian dialect of Akkadian were found in the early 2nd millennium BC karum. By the middle of the 2nd millennium a scribal community had grown up in Hattusa based on Syrian, Mesopotamian, and Hurrian input. This included the usual range of Akkadian and Sumerian language texts.[42][43][44]

One of the most important discoveries at the site has been the cuneiform royal archives of clay tablets from the Hittite Empire New Kingdom period, known as the Bogazköy Archive, consisting of official correspondence and contracts, as well as legal codes, procedures for cult ceremony, oracular prophecies and literature of the ancient Near East. One particularly important tablet, currently on display at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, details the terms of a peace settlement reached years after the Battle of Kadesh between the Hittites and the Egyptians under Ramesses II, in 1259 or 1258 BC. A copy is on display in the United Nations in New York City as an example of the earliest known international peace treaties.[45]

Although the 30,000 or so clay tablets recovered from Hattusa form the main corpus of Hittite literature, archives have since appeared at other centers in Anatolia, such as Tabigga (Maşat Höyük) and Sapinuwa (Ortaköy).

Sphinxes

[edit]

A pair of sphinxes found at the southern gate in Hattusa were taken for restoration to Germany in 1917. The better-preserved was returned to Turkey in 1924 and placed on display in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, but the other remained in Germany where it was on display at the Pergamon Museum from 1934 until it was moved to the Boğazköy Museum outside the Hattusa ruins[when?], along with the Istanbul sphinx reuniting the pair near their original location.[46]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gates, Charles (2011). Ancient cities: the archaeology of urban life in the ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-203-83057-4.

- ^ Bittel, Kurt, "Hattusha. The Capital of the Hittites", NewYork: Oxford University Press, 1970 ISBN 978-0195004878

- ^ Hawkins, David, "Writing in Anatolia: Imported and Indigenous Systems", World Archaeology, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 363–76, 1986

- ^ Hamblin, William J. Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. New York: Routledge, 2006.

- ^ Hopkins, David C., "Across the Anatolian Plateau: Readings in the Archaeology of Ancient Turkey", The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research, vol. 57, pp. v–209, 2000

- ^ Martino, Stefano de, "Hatti: From Regional Polity to Empire", Handbook Hittite Empire: Power Structures, edited by Stefano de Martino, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, pp. 205-270, 2022

- ^ Bryce, Trevor R., "The Annals and Lost Golden Statue of the Hittite King Hattusili I" in Gephyra 16, pp. 1-12, November 2018

- ^ Cline, Eric H. (2021). "Of Arms and the Man". 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton University Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780691208015.

- ^ Glatz, Claudia, and Roger Matthews, "Anthropology of a Frontier Zone: Hittite-Kaska Relations in Late Bronze Age North-Central Anatolia", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 339, pp. 47–65, 2005

- ^ Otten, Heinrich, "Keilschrifttexte aus Boghazköi 21 (Insbesondere Texte aus Gebäude A)", Berlin 1973

- ^ Güterbock, Hans G., "New Excavations at’ Boghazköy, Capital of the Hittites", Archaeology, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 211–16, 1953

- ^ Lewis, Leo Rich; Tenney, Charles R. (2010). The Compendium of Weapons, Armor & Castles. Nabu Press. p. 142. ISBN 1146066848.

- ^ Néhémie Strupler (2022). Fouilles archéologiques de la Ville Basse I (1935–1978): analyse de l'occupation de l'âge du Bronze de la Westterrasse / Néhémie Strupler (in French, German, and Turkish). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 134. doi:10.34780/V0E8-6UNA. ISBN 978-3-447-11942-9. Wikidata Q129697416.

- ^ Beckman, Gary (2007). "From Hattusa to Carchemish: The latest on Hittite history" (PDF). In Chavalas, Mark W. (ed.). Current Issues in the History of the Ancient Near East. Claremont, California: Regina Books. pp. 97–112. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ Manning, S.W., Kocik, C., Lorentzen, B. et al, "Severe multi-year drought coincident with Hittite collapse around 1198–1196 bc", Nature 614, pp. 719–724, 2023 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05693-y

- ^ Bryce, Trevor (2019). Warriors of Anatolia: A Concise History of the Hittites. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 264. ISBN 9781350140783.

- ^ Texier,Charles, "Description de l’ Asie Mineure, faite par ordre du Gouvernement Français de 1833 à 1837,et publiée parle ministre de l’ Instruction publique", Volumes I-III, Paris:Firmin-Didot, 1839-1849

- ^ Texier, Charles, "Rapport lu, le 15 mai 1835, à l'Académie royale des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres de l'Institut, sur un envoi fait par M. Texier, et contenant les dessins de bas-reliefs découverts par lui près du village de Bogaz-Keui, dans l'Asie mineure" [Report read on 15 May 1835 to the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Belle-lettres of the Institute, on a dispatch made by Mr. Texier and containing drawings of bas-reliefs discovered by him near the village of Bogaz-Keui in Asia Minor]. Journal des Savants (in French), pp. 368–376, 1835

- ^ Barth,Heinrich, "Reise von Trapezunt durch die nördliche Hälfte Klein-Asiens nach Scutariim Herbst 1858", Ergänzungsheft zu Petermann's geograph, Mittheilungen 3, Gotha:Justus Perthes, 1860

- ^ Perrot, Georges, Edmond Guillaume, and Jules Delbet 1872, "Exploration archéologique de la Galatie et de la Bithynie, d’ une partiede la Mysie, de la Phrigie,de la Cappadoce et duPontexécutéeen 1861", Volumes I-II, Paris:Firmin Didot, 1872

- ^ Perrot,Georges, "Une civilisation retrouvée: les Hétéens, leur écriture et leur art", Revuedes Deux-Mondes74 (15 July), pp. 303‒342, 1886

- ^ Alaura, Silvia, "Rediscovery and Reception of the Hittites: An Overview", Handbook Hittite Empire: Power Structures, edited by Stefano de Martino, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, pp. 693-780, 2022

- ^ Boissier, Alfred, "Fragments de tablettes couvertes de caractères cunéiformes, recueillies par M. Chantre et communiqués par M. Menant", Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 39 (4), pp. 348‒360, 1895

- ^ Crüsemann, Nicola, "Vom Zweistromlandzum Kupfergraben.Vorgeschichte und Entstehungsjahre (1899–1918) der Vorderasiatischen Abteilung der Berliner Museen vorfach-und kulturpolitischen Hintergründen, Jahrbuchder, Berliner Museen 42, Beiheft(Berlin:Gebr.MannVerlag), 2001

- ^ Winckler, Hugo, "Nach Boghasköi! Ein nachgelassenes Fragment", Der Alte Orient XIV/3, Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1913

- ^ Seeher, J, "Die Adresse ist: poste restante Yozgat Asie Mineure", Momentaufnahmen der Grabungskampagne 1907 in Boğazköy. In: J. Klinger, E. Rieken, C. Rüster (eds.), Investigationes Anatolicae: Gedenkschrift für Erich Neu, Wiesbaden, pp. 253-270, 2010

- ^ Alaura, Silvia, "NachBoghasköy!” Zur Vorgeschichte der Ausgrabungen in Boghazköy-Hattušaund zu denarchäologischen Forschungenbis zum Ersten Weltkrieg Darstellung und Dokumente, 13. SendschriftDOG, Berlin:Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, 2006

- ^ Bittel, Kurt (1983). "Quelques remarques archéologiques sur la topographie de Hattuša" [Some archaeological remarks on the topography of Hattusa]. Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 127 (3): 485–509.

- ^ Bittel, Kurt, "Reisen und Ausgrabungen in Ägypten, Kleinasien,Bulgarien und Griechenland 1930–1934", Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften und Literatur Mainz, Jg. 1998, Nr.5, Stuttgart:Franz Steiner Verlag, 1998 ISBN 9783515073288

- ^ Bittel, Kurt, "BOĞAZKÖY: The Excavations of 1967 and 1968", Archaeology, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 276–79, 1969

- ^ Jürgen Seeher, "Forty Years in the Capital of the Hittites: Peter Neve Retires from His Position as Director of the Ḫattuša-Boğazköy Excavations" The Biblical Archaeologist 58.2, "Anatolian Archaeology: A Tribute to Peter Neve" (June 1995), pp. 63-67.

- ^ P. Neve, "Boğazköy-Hattusha — New Results of the Excavations in the Upper City", Anatolica, 16, pp. 7–19, 1990

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen, "Büyükkaya II. Bauwerke und Befundeder Grabungskampagnen 1952–1955 und 1993–1998", Boğazköy-Hattuša 27, Berlin:de Gruyter, 2018

- ^ Schachner, Andreas, "Hattuscha.Auf der Such enach dem sagenhaften Großreich der Hethiter", München: C. H. Beck, 2011

- ^ Schachner, Andreas, "Hattusa andits Environs: Archaeology", in Hittite Landscape and Geography, Handbuch der Orientalistik I/121, eds. MarkWeeden, and Lee Z. Ullmann, Leiden/Boston: Brill, pp. 37‒49, 2017

- ^ Schachner, Andreas, "Die Ausgrabungen in Bogazköy-Hattusa 2018", Archäologischer Anzeiger. AA. Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, no. 1, 2019

- ^ H. Otten, "Die Bronzetafel aus Boğazköy: Ein Staatsvertrag Tuthalijas IV", Studien zu den Boğazköy-Texten, Beih. 1, Wiesbaden, 1988

- ^ Zimmermann, Thomas, et al., "The Metal Tablet from Boğazköy-Hattuša: First Archaeometric Impressions*", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 69, no. 2, pp. 225–29, 2010

- ^ Hansen, O., "A Mycenaean Sword from Boǧazköy-Hattusa Found in 1991", The Annual of the British School at Athens, vol. 89, pp. 213–15, 1994

- ^ Cline, E. H., "Aššuwa and the Achaeans: The 'Mycenaean' Sword at Hattušas and Its Possible Implications", The Annual of the British School at Athens, vol. 91, pp. 137–51, 1996

- ^ van den Hout, Theo, "Seals and Sealing Practices in Hatti-Land: Remarks À Propos the Seal Impressions from the 'Westbau' in Ḫattuša", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 127, no. 3, pp. 339–48, 2007

- ^ Beckman, Gary, "Mesopotamians and Mesopotamian Learning at Ḫattuša", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 35, no. 1/2, pp. 97–114, 1983

- ^ Matthew T. Rutz, "Mesopotamian Scholarship in Ḫattuša and the Sammeltafel KUB 4.53", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 132, no. 2, pp. 171–88, 2012

- ^ [1]Viano, M., "Sumerian Literary and Magical Texts from Hattuša", Contacts of Languages and Peoples in the Hittite and Post-Hittite World, Brill, pp. 189-205, 2023

- ^ Replica of Peace Treaty between Hattusilis and Ramses II - United Nations

- ^ "Hattuşa reunites with sphinx". Hürriyet Daily News. 18 November 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Bryce, Trevor, "Life and Society in the Hittite World", Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002 ISBN 9780199241705

- Bryce, Trevor, "Letters of the Great Kings of the Ancient Near East: The Royal Correspondence of the Late Bronze Age", London: Routledge, 2003 ISBN 9780415258579

- Bryce, Trevor, "The Kingdom of the Hittites" Rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005 ISBN 9780199240104

- W. Dörfler et al.: Untersuchungen zur Kulturgeschichte und Agrarökonomie im Einzugsbereich hethitischer Städte. (MDOG Berlin 132), 2000, 367–381. ISSN 0342-118X

- Gordin, Shai, "The Tablet and its Scribe: Between Archival and Scribal Spaces in Late Empire Period Ḫattusa", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 177–198, 2011

- Kloekhorst, Alwin and Waal, Willemijn, "A Hittite Scribal Tradition Predating the Tablet Collections of Ḫattuša?", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 109, no. 2, pp. 189–203, 2019

- Larsen, Mogens Trolle, "A Revolt against Hattuša", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 100–01, 1972

- Plerallini, Sibilla, "Observations on the Lower City of Hattusa: a comparison between the epigraphic sources and the archaeological documentation", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 325–358, 2000

- Neve, Peter (1992). Hattuša-- Stadt der Götter und Tempel : neue Ausgrabungen in der Hauptstadt der Hethiter (2., erw. Aufl. ed.). Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-1478-7.

- Neve, Peter. “The Great Temple in Boğazköy-H ̮attuša.” In Across the Anatolian Plateau: Readings in the Archaeology of Ancient Turkey. Edited by David C. Hopkins, 77–97. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research, 2002

- Kuhrt, Amelie, "The Hittites" In The Ancient Near East, c. 3000–330 BC. 2 vols. By Amelie Kuhrt, 225–282. London: Routledge, 1994

- Singer, Itamar, "A City of Many Temples: H ̮attuša, Capital of the Hittites", In Sacred Space: Shrine, City, Land: Proceedings of the International Conference in Memory of Joshua Prawer, Held in Jerusalem, 8–13 June 1992. Edited by Benjamin Z. Kedar and R. J. Z. Werblowsky, 32–44. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998

- Torri, Giulia, "The phrase ṬUPPUURUḪatti in Colophons from Ḫattuša and the Work of the Scribe Ḫanikkuili", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 135–144, 2011

- Torri, Giulia, "The Goldsmith Zuzu(l)li and the Find-spots of the Inventory Texts from Ḫattuša", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 43, no. 1–2, pp. 147–156, 2016

- [2] Weeden, Mark, "Back to the 13th or 12th Century BC?: The SÜDBURG Inscription at Boğazköy-Hattuša", in Devecchi, Elena and De Martino, Stefano - Anatolia between the 13th and the 12th century BCE, pp. 473–496, 2020

External links

[edit]- New Indo-European language discovered during excavation in Turkey - Phys.org September 21, 2023

- Excavations at Hattusha: a project of the German Institute of Archaeology

- Pictures of the old Hittite capital with links to other sites

- UNESCO World Heritage page for Hattusa

- Video of lecture at Oriental Institute on Boğazköy Archived 11 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Photos from Hattusa

- World Heritage Sites in Turkey

- Hattusa

- Populated places established in the 3rd millennium BC

- Populated places disestablished in the 2nd millennium BC

- 1834 archaeological discoveries

- Archaeological sites in the Black Sea region

- Archaeological sites of prehistoric Anatolia

- Buildings and structures in Çorum Province

- Former populated places in Turkey

- Geography of Çorum Province

- Hattian cities

- History of Çorum Province

- Hittite cities

- Hittite sites in Turkey

- Late Bronze Age collapse

- Capitals of former nations