History of YouTube

YouTube is an American online video-sharing platform headquartered in San Bruno, California, founded by three former PayPal employees—Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, and Jawed Karim—in February 2005. Google bought the site in November 2006 for US$1.65 billion, since which it operates as one of Google's subsidiaries.

YouTube allows users to upload videos, view them, rate them with likes and dislikes, share them, add videos to playlists, report, make comments on videos, and subscribe to other users. The slogan "Broadcast Yourself" used for several years and the reference to user profiles as "Channels" signifies the premise upon which the platform is based, of allowing anyone to operate a personal broadcasting station in resemblance to television with the extension of video on demand.

As such, the platform offers a wide variety of user-generated and corporate media videos. Available content includes video clips, TV show clips, music videos, short and documentary films, audio recordings, movie trailers, live streams, and other content such as video blogging, short original videos, and educational videos.

As of February 2017[update], there were more than 400 hours of content uploaded to YouTube each minute, and one billion hours of content being watched on YouTube every day. As of October 2020[update], YouTube is the second-most popular website in the world, behind Google, according to Alexa Internet.[1] As of May 2019[update], more than 500 hours of video content are uploaded to YouTube every minute.[2] Based on reported quarterly advertising revenue, YouTube is estimated to have US$15 billion in annual revenues.

YouTube has faced criticism over aspects of its operations, including its handling of copyrighted content contained within uploaded videos,[3] its recommendation algorithms perpetuating videos that promote conspiracy theories and falsehoods,[4] hosting videos ostensibly targeting children but containing violent or sexually suggestive content involving popular characters,[5] videos of minors attracting pedophilic activities in their comment sections,[6] and fluctuating policies on the types of content that is eligible to be monetized with advertising.[3]

Founding (2005)

| 2005 | July – Video HTML embedding |

|---|---|

| July – Top videos page | |

| August – 5-star rating system | |

| October – Playlists | |

| October – Full-screen view | |

| October – Subscriptions | |

| 2006 | January – Groups function |

| February – Personalized profiles | |

| March – 10-minute video limit | |

| April – Directors function | |

| May – Video responses | |

| May – Cell phone uploading | |

| June – Further personalized profiles | |

| June – Viewing history | |

| 2007 | June – Local language versions |

| June – Mobile web front end with RTSP streaming | |

| 2008 | March – 480p videos |

| March – Video analytics tool | |

| May – Video annotations | |

| December – Audioswap | |

| 2009 | January – Google Videos uploading halted |

| June – Launch of "YouTube XL" front end for television sets | |

| July – 720p videos and support for 3D video | |

| November – 1080p videos | |

| December – Automatic speech recognition | |

| December – Vevo launch | |

| 2010 | March – "Thumbs" rating system |

| July – 4K video | |

| December – Removal of groups feature | |

| 2011 | April – Live streaming |

| November – YouTube Analytics | |

| November – Feature film rental | |

| 2012 | March – Seek bar preview tooltips |

| June – Merger with Google Video | |

| 2013 | March‒June – Transition to the "One" channel layout |

| September – Removal of video responses feature | |

| September‒November – Google+ integration of comments sections | |

| 2014 | October – 60 fps videos |

| 2015 | March – 360° videos |

| June – 8k video | |

| October – YouTube Red launches (rebranded as YouTube Premium in 2018) | |

| 2016 | February – YouTube subscription service |

| April – live streaming with 360° and 1440p | |

| 2017 | January – Introduction of "Super Chat" |

| February – YouTube TV launches | |

| March – Ability to modify video annotations removed | |

| August – Logo changed and new "polymer" website version defaulted (preselected) | |

| September – Video Editor discontinued | |

| 2018 | June – Introduction of "Channel Memberships", "Merchandise" and "Premieres" |

| 2019 | January – Removal of annotations and AutoShare features |

| September – Visible subscriber counts abbreviated to three leading digits | |

| 2020 | January – Creators now must comply with COPPA |

February – Removal of option for legacy website version ("disable_polymer")[7] | |

| Spring – Removal of legacy "Creator Studio" | |

| May – Addition of chapters | |

| August – Removal of optional email notifications for uploads | |

| September – YouTube Shorts is launched; "Community Captions" removed | |

| 2021 | July – Introduction of "Super Thanks" |

| July – Purge of pre-2017 unlisted videos through mass-privatization. | |

| September – Introduction of "Super Stickers" | |

| November – Removal of public dislikes count | |

| 2022 | October – New UI Design |

| October – Handles | |

| 2023 | July – Crackdown on ad blockers |

| 2024 | April – Intensified crackdown on ad blockers, targeting third-party apps with ad blockers |

| September – Addition of YouTube Playables, implementation of ads on paused videos | |

| December – Crackdown on misleading video titles and thumbnails, known as "egregious clickbait" |

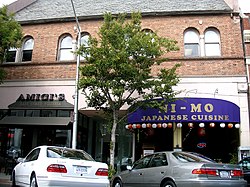

YouTube was founded by Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, and Jawed Karim, when they worked for PayPal.[9] Prior to working for PayPal, Hurley studied design at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania; Chen and Karim studied computer science together at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.[10] YouTube's initial headquarters was above a pizzeria and Japanese restaurant in San Mateo, California.[11]

The domain name "YouTube.com" was activated on February 14, 2005, with video upload options being integrated on April 23, 2005, with the slogan "Tune In, Hook Up" ─ the original idea of Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, and Jawed Karim. The concept was an online dating service that ultimately failed but had an exceptional video and uploading platform.[12] After the infamous Justin Timberlake and Janet Jackson Halftime show incident, they found it difficult to find any videos of it on the internet. After noticing that a video sharing platform did not exist, they dropped the dating aspect of the site.[13] The idea of the new company was for non-computer experts to be able to use a simple interface that allowed the user to publish, upload and view streaming videos through standard web browsers and modern internet speeds. Ultimately, creating an easy to use video streaming platform that wouldn't stress out the new internet users of the early 2000s.[14] The first YouTube video, titled Me at the zoo, was uploaded on April 23, 2005, and shows co-founder Jawed Karim at the San Diego Zoo and currently has over 120 million views and almost 5 million likes.[15][16] Hurley was behind the look of the website, creating the logo.[17] Chen made sure the page actually worked and that there would be no issues with the uploading and playback process. Karim was a programmer and helped in making sure the initial website was put together properly and helped in both design and programming.[17]

As of June 2005, YouTube's slogan was "Your Digital Video Repository".[18]

YouTube began as an angel-funded enterprise working from a makeshift office in a garage. In November 2005, venture firm Sequoia Capital invested an initial $3.5 million,[19] and Roelof Botha (a partner of the firm and former CFO of PayPal) joined the YouTube board of directors. In April 2006, Sequoia and Artis Capital Management invested an additional $8 million in the company, which had experienced significant growth in its first few months.[20][failed verification]

As of December 2005, the number of commenters' videos, favourites, and friends was directly indicated in the comment section, as well as a video's backlinks, comment counts in suggested videos, and rating indicator in video listings search results and channel pages. The site slogan was "Broadcast yourself. Watch and share your videos worldwide!", which would later become just "Broadcast yourself".[21] Later, while some of these indicators were removed, the watch page displayed playlists linking back to a video as of 2007, like SoundCloud does as of 2022.[22]

Growth, purchase by Google, and Person of the Year (2006)

After opening on a beta service in April 2005 YouTube.com was trafficking around 30,000 viewers a day within just a few months of launch. After launching eight months later they would be hosting well over two million viewers a day on the website. By March 2006 the site had more than 25 million videos uploaded and was generating around 20,000 uploads a day.[23] During the summer of 2006, YouTube was one of the fastest growing sites on the World Wide Web,[24] hosting more than 65,000 new video uploads. The site delivered an average of 100 million video views per day in July.[25] However, this did not come without any problems, the rapid growth in users meant YouTube had to keep up with it technologically speaking. They needed new equipment and wider broadband internet connection to serve an ever growing audience. The increasing copyright infringement problems and lack in commercializing YouTube eventually led to outsourcing to Google who later failed in their own video platform "Google Video".[23] It was ranked the fifth-most-popular website on Alexa, far out-pacing even MySpace's rate of growth.[26] The website averaged nearly 20 million visitors per month according to Nielsen/NetRatings,[25] with around 44% female and 56% male visitors. The 12- to 17-year-old age group was dominant.[27] YouTube's pre-eminence in the online market was substantial. According to the website Hitwise.com, YouTube commanded up to 64% of the UK online video market.[28]

YouTube entered into a marketing and advertising partnership with NBC in June 2006.[29]

The first targeted advertising on the site came in February 2006 in the form of participatory video ads, which were videos in their own right that offered users the opportunity to view exclusive content by clicking on the ad.[30] The first such ad was for the Fox show Prison Break and solely appeared above videos on Paris Hilton's channel.[30][31] At the time, the channel was operated by Warner Bros. Records and was cited as the first brand channel on the platform.[31] Participatory video ads were designed to link specific promotions to specific channels rather than advertising on the entire platform at once. When the ads were introduced, in August 2006, YouTube CEO Chad Hurley rejected the idea of expanding into areas of advertising seen as less user-friendly at the time, saying, "we think there are better ways for people to engage with brands than forcing them to watch a commercial before seeing content. You could ask anyone on the net if they enjoy that experience and they'd probably say no."[31] However, YouTube began running in-video ads in August 2007, with preroll ads introduced in 2008.[32]

On October 9, 2006, it was announced that the company would be purchased by Google for US$1.65 billion in stock, which was completed on November 13. At that time it was Google's second-largest acquisition.[33] This kickstarted YouTube's rise to becoming a global media dominator, creating a multi-billion-dollar business that has surpassed most television stations and other media markets, sparking success for many YouTubers.[14] Indeed, YouTube as an entity generated more than twice the amount of revenues in 2018 than any major TV network (with $15 billion compared to NBC's $7 billion).[34] The agreement between Google and YouTube came after YouTube presented three agreements with media companies in an attempt to avoid copyright-infringement lawsuits. YouTube planned to continue operating independently, with its co-founders and 68 employees working within Google.[35] Viral videos were the main factor for YouTube's growth in the beginning of its early days with Google, for example Evolution of Dance, Charlie Bit My Finger, David After the Dentist, and more viral videos.[36]

Google's February 7, 2007, SEC filing revealed the breakdown of profits for YouTube's investors after the sale to Google. In 2010, Chad Hurley's profit was more than $395 million while Steve Chen's profit was more than $326 million.[37]

In 2006, Time magazine featured a YouTube screen with a large mirror as its annual "Time Person of the Year". It cited user-created media such as that posted on YouTube and featured the site's originators along with several content creators. The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times also reviewed posted content on YouTube in 2006, with particular regard to its effects on corporate communications and recruitment. PC World magazine named YouTube the ninth of its Top 10 Best Products of 2006.[38] In 2007, both Sports Illustrated and Dime Magazine featured positive reviews of a basketball highlight video titled, The Ultimate Pistol Pete Maravich MIX.[39]

Continued growth and functionality (2007–2013)

It is estimated that in 2007, YouTube consumed as much bandwidth as the entire Internet in 2000.[40]

YouTube's early website layout featured a pane of currently watched videos, as well as video listings with detailed information such as full (2006) and later expandable (2007) descriptions, as well as profile pictures (2006), ratings, comment counts, and tags.[41][42] Channels' pages were equipped with standalone view counters, bulletin boards, and were awarded badges for various rank-based achievements, such as "#15 – Most Subscribed (This Month)", "#89 – Most Subscribed (All Time)", and "#15 – Most Viewed (This Week)". Channels themselves had a view count indicator.[43]

In March 2007, YouTube launched the YouTube Awards, an annual competition in which users voted on the best user-generated videos of the year.[44] The awards were presented twice, in 2007 and 2008. Video contests with prizes existed as early as December 2005, possibly earlier.[45][46]

At "youtube.com/browse", there were various web feeds, including a list of the videos most recently uploaded to the site, suggesting an upload rate of approximately two videos per minute as of April 2007.[47] Other feeds included the most viewed, highest rated, most discussed, most "favourited", most backlinked, staff picks, videos with most video responses, and "Watch on mobile". Some feeds could be filtered by categories including but not limited to "Autos & Vehicles", "Music", "News & Politics", "People & Blogs", "Travel & Places", and feeds except "Most recent" (where inapplicable) could be filtered by time range ("Today", "This week", "This month", "All time"). An uncaptioned Verizon Wireless logo resided on the "Watch on mobile" feed, suggesting a partnership.[48]

In June 2007, YouTube launched a mobile web front end, where videos are served through RTSP.[49]

In July 2007, YouTube partnered with Verizon Wireless to enable mobile phone users to submit videos through Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS).[50]

On July 23, 2007, and November 28, 2007, CNN and YouTube produced televised presidential debates in which Democratic and Republican US presidential hopefuls fielded questions submitted through YouTube.[51][52]

In December 2007, YouTube launched the Partner Program, which allows channels that meet certain metrics (currently 1000 subscribers and 4000 public watch hours in the past year)[53] to run ads on their videos and earn money doing so.[32]

As of 2007, the youtu.be domain served as an image hosting service for the site, but was subsequently repurposed for shortening watch page URLs.[54][55]

Around 2008, "Warp Player" was tested out. It was an experimental interactive interface for browsing videos, where links to videos appeared as thumbnails, visualized in a floating and navigable net.[56]

Starting in 2008, the site featured a series of April Fools' pranks each year until 2016. At the first, on April 1, 2008, all video links on the front page were redirected to Rick Astley's music video "Never Gonna Give You Up", a prank known as "rickrolling". The other gags are covered in YouTube § April Fools Gags.

In June 2008, video annotations were introduced. Users were able to add text boxes and speech bubbles at any desired location and custom sizes in various colours, and optionally with a link and short pausing, allowing for interactive videos. In February 2009, the feature was extended to allow for collaboration, meaning uploaders could invite others to edit their video's annotations.[57][58][59] On May 2, 2017, annotations were locked from editing, and on January 15, 2019, they were entirely shut down.

Since October 2008, deep linking to a playback position through a timestamped URL is possible.[60] A new "theatre view" mode was added as well, allowing the video player to optionally extend over both page columns.[61]

As part of the "TestTube" program which allows users to opt to use experimental site features, a comment search feature accessible under /comment_search was implemented in October 2009. YouTube Feather was introduced in December as a lightweight alternative website front-end intended for countries with limited internet speeds.[62] Both were removed subsequently.[63]

In November 2008, YouTube reached an agreement with MGM, Lions Gate Entertainment, and CBS, allowing the companies to post full-length films and television episodes on the site, accompanied by advertisements in a section for US viewers called "Shows". The move was intended to create competition with websites such as Hulu, which features material from NBC, Fox, and Disney.[64][65]

YouTube was awarded a 2008 Peabody Award and cited as being "a 'Speakers' Corner' that both embodies and promotes democracy".[66][67]

In early 2009, YouTube registered the domain www.youtube-nocookie.com for videos embedded on United States federal government websites.[68][69] It is currently used in "privacy-preserving mode", an option available for embedded videos, allowing for video playback without the need to accept cookies from YouTube, as well as allowing users to watch videos without affecting their watch history or suggestions on YouTube.com.[70][71]

In November of the same year, YouTube launched a version of "Shows" available to UK viewers, offering around 4,000 full-length shows from more than 60 partners.[72]

In April 2009, YouTube launched their earliest HTML5 video player experiments.[73]

Throughout 2009, the alphabetical sorting of YouTube's "AudioSwap" feature helped popularizing Alexander Perls' "009 Sound System" music project through frequent use in videos.[74][75]

In June 2009, YouTube XL was launched. It was a front-end for viewing and browsing on television sets, and as such, for use on stationary game consoles with web browser, such as the Nintendo Wii. Its appearance varied depending on device.[76][77]

In July 2009, developers of YouTube placed a site notice that warned about the impending deprecation of support for Internet Explorer 6, prompting its users to upgrade their browser. It is claimed that they represented 18% of site traffic at that time. Within months of the announcement, traffic from Internet Explorer 6 reduced to less than half, and traffic from other browsers surged accordingly.[78] Support for its successor, Internet Explorer 7, was deprecated in the second half of 2012.[79]

3D stereoscopic video was first implemented in July 2009.[80] In September 2011, a "2D-to-3D conversion tool" was added.[81] Side-by-side 3D videos could be made to appear as stereoscopic 3D (anaglyph 3D). Since late 2018, it is only available with a flag set in the video file's metadata.[82][83]

In late 2009, YouTube introduced automatic captioning of videos through speech recognition. Initially only available in English, it was expanded to six European languages in late 2012.[84][85] The same day, some videos has difficulted to be written inaccurate[citation needed].

Entertainment Weekly placed YouTube on its end-of-the-decade "best-of" list In December 2009, describing it as: "Providing a safe home for piano-playing cats, celeb goof-ups, and overzealous lip-synchers since 2005."[86]

The transition from ActionScript version 2 to 3 was initiated in late 2009.[87]

In January 2010, an overhaul of the watch page was first tested as beta. It was made default on March 31st.[88][89]

At a similar time, "YouTube Disco" was launched, a music discovery service. It closed in October 2014.[90][91]

In January 2010,[92] YouTube introduced an online film rentals service which is currently available only to users in the US, Canada and the UK.[93][94] The service offers over 6,000 films.[95] In March 2010 YouTube began free streaming of certain content, including 60 cricket matches of the Indian Premier League. According to YouTube, this was the first worldwide free online broadcast of a major sporting event.[96]

On March 31, 2010, YouTube launched a new design with the aim of simplifying the interface and increasing the time users spend on the site. Google product manager Shiva Rajaraman commented: "We really felt like we needed to step back and remove the clutter."[97]

Until then, a five-point video rating system that used star icons was in use. Users were able to rate videos with one to five "stars", where more indicated greater preference. This rating system was replaced with a bidirectional one using positive "like" and negative "dislike" ratings, citing low numbers of users rating other than the most (5) or least (1) stars. Ratings of three or more "stars" were converted to "likes" and such below accordingly to "dislikes".[98] This change was first announced in September 2009.[99] As a reference, widely known sites that operate a five-level rating system as of 2021 are IMDb, Amazon, and the Google Play. Additionally, videos previously marked as "Favorite" have been moved to a playlist for each user, the video description was moved from the right side to below the video viewport, the profile picture was removed from the watch page, and the "More From: channel name" section in the side pane above "Related Videos" was moved to button above the video player labelled with the number of channels' public videos which allowed quickly accessing other videos of a channel without having to navigate to the channel page. Recommended videos since no longer appear in a scrollable box.[98]

Later the same month, the control section of the Flash-based video player was redesigned to feature a dedicated row for the seek bar, as is used since, as of 2021.[100]

In May 2010, it was reported that YouTube was serving more than two billion videos a day, which was "nearly double the prime-time audience of all three major US television networks combined".[101] According to May 2010 data published by market research company Comscore, YouTube was the dominant provider of online video in the United States, with a market share of roughly 43 percent and more than 14 billion videos viewed during May.[102]

Around 2010, an easter egg of the Flash-based video player was discovered, where pressing the arrow key while the dotted loading animation is visible initiates a Snake game formed by the dots. The HTML5-based player, which initially had the same dotted loading animation, did not support it.[103][104]

In September 2010, a unique full-page interactive TippEx advertising campaign was launched on YouTube, where the entire watch page was simulated in a Flash viewport. A hunter who does not wish to shoot a bear grabs outside of the video's viewport to reach for a Tipp-Ex tape roller, and uses it to cover the word "shoots" in the video titled "A hunter shoots a bear". Users were able to enter words in the gap, which lead to different unlisted videos with a multitude of pre-recorded reactions.[105]

In October 2010, Hurley announced that he would be stepping down as the chief executive officer of YouTube to take an advisory role, with Salar Kamangar taking over as the head of the company.[106]

James Zern, a YouTube software engineer, revealed in April 2011 that 30 percent of videos accounted for 99 percent of views on the site.[107]

Live streaming was introduced in April 2011, initially rolled out to select users and later expanded.[108]

In May 2011, YouTube reported on the company blog that the site was receiving more than three billion views per day, and that 48 hours of footage are uploaded every minute.[109] Later, in January 2012, YouTube stated that the figure had increased to four billion videos streamed per day and sixty hours.[110]

In June 2011, YouTube started experimenting with reaction buttons, allowing users to react to videos with a multitude of expressions, similar to Facebook's 2016 reaction buttons, though YouTube removed reaction buttons soon after.[111][112]

Since July 2011, the word "YouTube" is placed after the video title in the watch page title, whereas before it until then.[113]

During November 2011, the Google+ social networking site was integrated directly with YouTube and the Chrome web browser, allowing YouTube videos to be viewed from within the Google+ interface.[114] In December 2011, YouTube launched a new version of the site interface, with the video channels displayed in a central column on the home page, similar to the news feeds of social networking sites.[115] It is based on a similar user interface was put to test as early as July 2011 under the code name "Cosmic Panda".[116] At the same time, a new version of the YouTube logo was introduced with a darker shade of red, which was the first change in design since October 2006.[117] A comment section that refreshes automatically to resemble a stream of chat messages was initially tested around that time.[118]

In 2012, YouTube reported that roughly 60 hours of new videos are uploaded to the site every minute, and that around three-quarters of the material comes from outside the U.S.[109][110][119] The site has eight hundred million unique users a month.[120]

As of 2012, users were able to rate playlists, and videos' view counts and playlists' total duration were indicated on playlist pages.[121]

In March 2012, preview tooltips for the video player's seek bar were introduced on the desktop web front end, initially available on select videos and gradually rolled out. This feature allows the viewer to additionally preview portions of a video by hovering above the seek bar with the mouse cursor, whereas only the time stamp was indicated before. Dragging the position handle of the video player additionally showed surrounding preview images in a film strip layout. For videos longer than 90 minutes, a magnified portion of the seek bar was additionally displayed since to facilitate fine seeking.[122]

On March 30 and 31, 2012, in the course of earth hour, the site used a light-on-dark color scheme (or "dark theme"). A switch was located left to the video title, allowing to toggle back if desired. This is the earliest known use of a light-on-dark color scheme on the site. The switch was removed the following day and the bright background was restored.[123][124]

From 2010 to 2012, Alexa ranked YouTube as the third most visited website on the Internet after Google and Facebook.[125]

In late 2011 and early 2012, YouTube launched over 100 "premium" or "original" channels. It was reported the initiative cost $100 million.[126] Two years later, in November 2013, it was documented that the landing page of the original channels became a 404 error page.[127][128] Despite this, original channels such as SourceFed and Crash Course were able to become successful.[129][130]

An algorithm change was made in 2012 that replaced the view-based system for a watch time-based one that is credited for causing a surge in the popularity of gaming channels. It was meant to reduce the impact of channels releasing low effort videos for profit.[131]

In October 2012, for the first-time ever, YouTube offered a live stream of the U.S. presidential debate and partnered with ABC News to do so.[132] The peak in concurrent views on any live stream was reached on October 14, where over eight million watched a sky dive.[133]

On October 25, 2012, The YouTube slogan (Broadcast Yourself) was taken down due to the live stream of the U.S. presidential debate.

In October 2012, YouTube introduced the ability to add a translucent and overlayed custom icon at a corner of all own videos, which can link to the channel page or a specified video. The feature was initially named "InVideo Programming".[134]

YouTube relaunched its design and layout in early December 2012 to resemble the mobile and tablet app version of the site.[citation needed] Notable changes of the watch page are the relocation of title and the "Subscribe" button from above to below the video's viewport, the removal of the button that opened a section above the video viewport showing other videos of the same channel without needing to leave the watch page, and the removal of a button-sized banner located above the viewport, which could contain a custom image, popularly icons and text logos.[135] Playlists on the watch page, which were formerly displayed as collapsible horizontal list fixed at the page bottom, became a scrollable vertical list next to the video player.[136]

On December 21, 2012, the "Gangnam Style" music video by South Korean musician PSY became the first YouTube video to surpass one billion views.[137]

As of early 2013, YouTube video recommendations contain both videos and channels.[138]

Rise of YouTube stars and feature trim down (2013–2019)

In early 2013, YouTube introduced a new layout for channels known as "One Channel", which added the ability to put playlists into shelves on the channel front page, but removed custom backgrounds. Formerly unified channel pages were separated into multiple sub pages such as "Videos", "Playlists", "Discussion" (channel comments), "Channels" (featured by user), and "About" (channel description, total video view count, join date, outlinks). This layout was initially optional, with a transitional period taking place between March 8 and June 5 after which it has been made permanent for all users. This layout formed the basis of the one currently used as of 2024.[139]

In March 2013, the number of unique users visiting YouTube every month reached 1 billion.[140] In the same year, YouTube continued to reach out to mainstream media, launching YouTube Comedy Week and the YouTube Music Awards.[141][142] Both events were met with negative to mixed reception.[143][144][145][146]

Automatically generated playlists known as "YouTube Mix" were first rolled out in April 2013.[147] A year later, the feature was rolled out to the mobile app for Android OS.[148] A similar feature called "YouTube Radio" for continuous music playback in resemblance to radio stations was tested in February 2015.[149]

Since approximately July 9, 2013, the first page of videos' comment section is no longer included in the watch page's static HTML source code, but instead loaded subsequently through AJAX.[150]

A picture-in-picture mode for browsing within the app while watching was introduced to the mobile app in August 2013.[151] At a similar time, channel hover cards were first implemented to the desktop site, which are tooltips previewing channel details that appear when pointing at channel names with the mouse cursor. These details include the header image, subscriber count, subscribe button, and a snippet of the channel description text.[152] Additionally, a play symbol ("▶") to indicate a playing video in the page title was added to the desktop site. But it has been rendered obsolete the following years as desktop web browsers were equipped with an indicator for audio-playing tabs.[153][154][155]

On September 12, 2013, the "video responses" feature introduced back in May 2006 was discontinued, citing a low click-through rate. It allowed users to respond to videos through a new or existing video which appeared above the comment section.[156]

In the same month, YouTube's comment system on channel pages, and two months later on videos, was integrated to Google's social network site "Google+", since which a Google Brand Account is required to be able to comment. This change also included the ability to edit existing comments and include URLs in comments, with the removal of the 500 characters limit and negative user ratings from comments. Channels created prior as standalone YouTube accounts using its legacy registration form have been grandfathered to a /user/ URL.[157][158]

In November 2013, YouTube's own YouTube channel surpassed Felix Kjellberg's PewDiePie channel to become the most subscribed channel on the website. This was due to auto-suggesting new users to subscribe to the channel upon registration.[159]

Users of the mobile app can reply to comments since April 2014.[148]

In June 2014, YouTube replaced the classic Inbox feature with a new private messaging system, which – like comments – required users to have their YouTube accounts linked with a Google+ profile, which was subsequently moved over to Google Brand Accounts. Legacy Inbox messages could be viewed and downloaded up until December 1.[160][161]

In October 2014, videos' frame rate limit was increased from 30 to 60, allowing for a smoother and more realistic appearance. It was initially only available with Google Chrome and later expanded to other browsers. 60fps are only available at 720p resolution and above.[162]

In November 2014, YouTube launched a paid subscription service initially named "Music Key", featuring background playback, the integrated ability to download music for offline use, and no advertisement breaks.[163] Almost a year later, in October 2015, it was rebranded to "YouTube Red" and its scope expanded beyond music.[164] It was rebranded again in May 2018 to "YouTube Premium", and its availability expanded across countries.[165] Google's other music streaming service Play Music was merged with YouTube Music in May 2020, as the latter is a more recognized brand.[166]

Support for the dedicated YouTube application on the Sony PlayStation Vita game console was deprecated in January 2015, for the Nintendo Wii and Wii Mini in June 2017, and for the Nintendo 3DS in August 2019.[167][168][169]

In March 2015, YouTube introduced the ability to automatically publish videos at a scheduled time,[170] as well as "info cards" and "end cards", which allow referring to videos and channels through a notification at the top right of the video at any playback time, and thumbnails shown in the last 20 seconds. In contrary to annotations, these work in the mobile app too, though are far less customizable.[171][172]

360-degree video was launched in March 2015. A year later, in April 2016, the ability to live stream 360-degree video was launched. Additionally, live streaming resolution was elevated to 1440p and 60 frames per second, and support for the EIA-608 and CEA-708 formats were added for embedded captioning.[173]

In August 2015, "YouTube Gaming" was launched. It was a separate web and mobile front end showing only gaming-related content, featuring a similar layout but somewhat modified appearance compared to the main site, and a light-on-dark color scheme well before the feature was introduced to the main site.[174] It was discontinued in March 2019 and merged with the main site.[175]

At a similar time, the view count indicator was patched to become continuous instead of temporary halting at 301 views (indicated as "301+") for hours, reportedly to calculate and deduct "counterfeit views". This phenomenon was first documented in June 2012. As an easter egg, the view counter of the video by mathematics channel "Numberphile" discussing this phenomenon was set to remain at 301.[176][177][178]

In December 2015 and January 2016, direct uploading through email and webcam recording respectively were removed. The former existed to support cell phones with limited web browsing capabilities.[179][180]

Around January 30, 2016, the dedicated "/all_comments" page which served videos' comments as static HTML was removed as well, and redirected to videos' main watch page, "/watch".[181] At some point, "/all_comments" displayed the absolute date (e. g. "Aug 26, 2014") rather than the relative (e. g. "1 week ago") on older comments,[182] as well as 500 comments per page like on legacy Reddit and three preview thumbnails from a video.[79]

In mid-2016, the earliest experiments with a redesigned desktop web front end were conducted. It follows the "material design" language and is based on the "Polymer" web framework.[183] A light-on-dark color scheme, also known as "dark mode" or "dark theme", was first implemented in May 2017, though it wouldn't release until August 2017[184]

The earliest trials with a new channel sub page named "Community" as an impending replacement for "Discussion" were conducted on select channels in September 2016.[185]

In November 2016, the ability to "heart" and pin comments under own videos was added. "Hearting" visibly marks comments under own videos to signify appreciation; a select comment can be pinned so to remain on top of the section.[186]

Since December 2016, YouTube started rolling out a progress bar at thumbnails' bottom edge, indicating the watch progress of previously watched videos, starting with the iOS app.[187]

Live streaming from the mobile app was rolled out in early 2017, initially only available to channels with at least 10,000 subscribers.[188]

Annotations became uneditable on May 2, 2017. Since then, users were only able to remove all annotations from individual videos. Parts of the feature such as collaborative annotations and pause markings were already removed earlier.[189][190]

On August 29, 2017, YouTube changed both their logo and the design of their desktop website. The "Tube" part of the logo is no longer surrounded by the shape resembling a CRT television. The shape moved left besides the "YouTube" word mark and has a white triangle resembling a play button. Their new "Polymer" web front based on that first tested in mid-2016 was made default for visitors.[191][183]

As of 2017, notes could be added to videos within playlists by the creator of the playlist.[192]

In January 2018, a musical note badge replaced the check mark to denote account verification status for music artists. YouTube refers to such channels as "artist channels", a feature introduced months prior with a slightly different channel layout.[193]

In March 2018, a picture-in-picture mode was introduced to the desktop web site that the fixes the video player to the lower right corner of the screen for browsing and searching without having to leave the video. A fixed "mini player" top bar appearing when scrolling down and containing the video and controls for watching while browsing comments was intermittently tested.[194][195]

On April 3, 2018, a shooting took place at YouTube headquarters.[196]

In June 2018, a "Premiere" feature was added, where a video can be broadcast like a live stream after uploaded, and users can discuss in a live chat like they can in live streams. Before the video starts, an animated two-minute preroll with the soundtrack "Space Walk" by "Silent Partner" is played. A premiere can be set to start immediately after upload or at a scheduled time, though scheduled publications existed since March 2015.[197][198]

On July 9, 2018, the private messaging feature has been removed from "Creator Studio", purging existing messages.[199]

In July 2018, it was reported that the site's "Polymer" redesign slowed performance significantly on non-Chromium browsers compared to the legacy, HTML-based version of the front end.[200][201][202]

In August 2018, the search result counter resembling that of Google Search was removed.[203] The change occurred one month after the airing of a popular TED talk with a prominent mention of a result count of 10 million for a search for surprise eggs.[204] Whether it is related is unknown.

In October 2018, YouTube announced launching a fund program for educational creators, to which creators with a minimum of 25.000 subscribers and a demonstrated expertise in their field could apply through an agreement.[205]

In November 2018, YouTube rolled out a "Stories" feature in resemblance to Snapchat and Instagram Stories, where videos are automatically deleted ("expire") after a day. The feature was tested as "YouTube reels" earlier that year, and is only accessible through the native mobile apps and not implemented on the websites.[206] This feature was disabled on June 26, 2023, citing access being limited, and poor promotion. Existing stories would remain for 7 days after uploading was disabled.[207][208]

Modern era, continued feature trim down and refinement (2019–present)

The removal of existing annotations on all videos was announced around November 27, 2018, and occurred as scheduled on January 15, 2019.[209][210][211]

On January 31, 2019, AutoShare was removed. The feature allowed users to opt to automatically broadcast actions such as liking videos, playlist additions, new uploads, and earlier added subscriptions to Google+ and Twitter, and the channel feed.[212][213]

On the same day, the dedicated section for video credits like "Starring", "Written by", and "Edited by" was removed from videos' description box, citing low usage. Addition of such was already disabled since November 27, 2018, the same day on which the definite annotation removal was announced.[214][215]

Dedicated "learning playlists" that do not include algorithmic recommendations, have a distinct page layout, and allow dividing videos into sub-sections of lessons, were introduced in July 2019.[216]

Since September 2019, channels' publicly displayed subscriber counts are abbreviated to the leading three digits and rounded down, including those served through the site API. This means, for example, that a subscriber count of 102,516 is indicated as "102K" or "102.000". This change disabled third-party real-time subscriber count indicators such as that of Social Blade, and diminished the accuracy of historical log data. Exact counts remained accessible to channel operators through the "YouTube Studio" web application.[217][218]

Also in September 2019, the new "direct messaging" system was removed two years after introduction. This was a distinct system not to be confused with Creator Studio messages, which was removed in July 2018 after replacing the legacy Inbox feature – which existed since YouTube's early years – four years prior.[219][220]

Another change reported in September 2019 was a strictening of the account verification procedure. Previously, the sole criterion for verification is said to have been a subscriber count of at least 100.000, whereas since, YouTube reports requiring what they describe as a "proof of authenticity", incorporating notability outside of YouTube. A change of the verification badge's appearance from a symbol into a highlighted channel name was also announced, but has not been implemented since.[221]

In late October 2019, a list layout with snippets of videos' descriptions, slightly in resemblance of YouTube in its early years, was tested for a short time, then the shelf (or "grid") layout was restored.[222] Soon after, in early November, the size of videos' thumbnails on the home page was increased and profile pictures added. A similar layout was first tested in August that year, though the test used even larger thumbnails, resulting in fewer videos per row.[223][224][225]

In November 2019, YouTube had announced that the service would phase out the classic version of YouTube Studio to all YouTube creators by the spring of 2020.[226] It was available and accessible to some YouTube creators by the end of March 2020.[227]

In that month, a watch queue feature was added, which resembles the intermittently removed "QuickList" feature that was originally introduced in 2006.[228][229]

In late 2019, the mobile website got equipped with a standalone HTML5 video player interface rather than displaying browsers' built-in HTML5 player.[230]

Since December 2019, users are no longer able to share the automatically generated playlist of positively rated videos.[231]

Beginning January 2020, video creators have to mark whether a video is made for kids or not, YouTube citing compliance with the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act as the reason for the change.[232]

The ability to add polls with up to five options as video info cards was removed in May 2020.[233]

The ability to visibly divide the video player's seek bar into chapters using time stamp lists in the video description was introduced in May 2020.[234] Later that year, in November, the platform started experimenting with automatic estimation of videos' chapters in November 2020 using artificial intelligence that detects in-video chapter titles.[235]

Around May 2020, the "HD" badge disappeared from the 720p option in the resolution selector of the video player, raising the minimum resolution option with a badge to 1080p.[236]

In June 2020, YouTube phased out the ability to use categories.

In August 2020, automated Email notifications of newly published videos by user-opted channels have been shut down, citing low numbers of users who open them. Only push notifications (mobile) and internal web notifications (desktop) of new uploads remained.[237]

The "Community Captions" feature which allowed viewers to contribute captions for public display upon approval by the video uploader was removed in September 2020.[238][239]

On September 14, 2020, YouTube added the YouTube Shorts section to the website.[240]

Since September 2020, YouTube blocks embedding of videos marked as "age-restricted", meaning deemed unsuitable for minors. Their preview thumbnails appear blurred in search results since October 2021.[241]

YouTube launched a feature in live chat for chat streams where the creator can enable subscriber only mode.[242]

In December 2020, comments on so-called "art tracks" which are automatically posted music tracks with album cover, frequently on "topic channels",[243][244] have been permanently deactivated.[245]

In July 2021, all unlisted videos prior to 2017[a] were set to private, making them unplayable except on channels whose owners intervened by manually opting out.[246][247]

Around that time, a study conducted by web archivists has concluded that over half of the videos which were on air on the platform around 2010 were no longer available by 2021. Such videos were either reversibly set to "private" or irreversibly erased, the latter of which occurred for the majority of those videos. Videos are taken down as a result of individual policy or copyright violation, channel terminations, retroactive policy changes, and voluntarily by uploaders.[248]

On August 24, 2021, YouTube sent a cease and desist to the developers of Groovy, a Discord bot which enabled audio from YouTube videos to be played in Discord voice chats, as the bot violated YouTube's Terms of Service.[249][250][251] A YouTube spokesperson stated, "We notified Groovy about violations of our Terms of Service, including modifying the service and using it for commercial purposes."[249] In a message announcing the bot's closure, the owner of Groovy, Nik Ammerlaan, said, "Groovy has been a huge part of my life over the past five years. It started because my friend's bot sucked and I thought I could make a better one."[249]

In September 2021, the dedicated "view attributions" page was discontinued citing low usage.[252]

In October 2021, YouTube experimented with indicating the most watched parts of a video through a solid line chart appearing on the seek bar in the mobile app to facilitate watchers finding relevant parts.[253] Additionally, an experiment with multilingual audio tracks was started, allowing creators to add audio tracks of multiple languages to one video. The watcher can switch the language during playback, similarly to a multilingual DVD-Video.[254]

All channels' "Discussion" sub page is to be ultimately discarded on October 12, 2021. The feature was known as "Channel comments" in the site's early age, and served as channels' general comment section. Previously, it was gradually replaced with the "Community" page that first rolled out to select channels, and since approximately 2018 to channels surpassing a subscriber count threshold that decreased over time, discarding existing discussions. During the same day, YouTube lowered the threshold to the Community page from 1000 to channels with at least 500 subscribers.[255][256] The "Discussion" page was closed down earlier on the mobile site.[257]

On November 10, 2021, YouTube announced the removal of videos' count for negative user ratings (also known as "dislikes" and "thumbs down"), reportedly to protect creators from online harassment. The dislike count remains solely visible to respective channel owners. This change was first tested with select users in March and again in July.[258][259][260]

In the second half of 2022, the option to sort the videos of a channel in reverse chronological order, by oldest first, has been phased out. It was reportedly first removed from the mobile application and later from the website. Only the options to sort by the newest videos first and the most viewed remain.[261][262] However, later on May 4, 2023, YouTube announced that they will bring the said option back.[263]

On October 10, 2022, YouTube introduced "handles", whereby channels can be referred to by a more memorable web address (URL) starting with youtube.com/@. Channels' legacy custom URL formats, (/c/) and (/user/), were converted to handles. On the same day, YouTube announced that they will be rolling out handles for all users over the coming weeks, whereas previously, custom URLs required channels to pass a hundred subscribers first. Channels without a previously specified custom URL were provided with an automatically generated handle containing their displayed channel name followed by numbers, which is for use until the user specifies a custom handle. The legacy URL formats, however, still remain available to this day.[264] The same month, YouTube updated the subtitles to put uppercase letters in initial words[citation needed].

In July 2023, YouTube began blocking videos for users of ad blockers.[265]

In April 2024, YouTube expanded its crackdown on ad blockers, targeting third-party apps that have the ability to turn off ads.[266] Attempting to watch a video using such apps could lead to buffering issues or the error message: "The following content is not available on this app", prompting the user to watch the video on the official app instead. The company says that its terms of service don't allow "third-party apps to turn off ads because that prevents the creator from being rewarded for viewership".[267]

On May 28, 2024,[268] YouTube began adding "YouTube Playables" to its home page. Playables are video games that can be played directly on YouTube without the need of downloading them.[269]

On September 19, 2024, YouTube added ads to the sides of videos when paused.[270]

On December 20, 2024, YouTube introduced new guidelines prohibiting videos with clickbait titles to enhance content quality and combat misinformation. The platform aims to penalize creators using misleading or sensationalized titles, with potential actions including video removal or channel suspension.[271] According to YouTube, this guideline will gradually roll out in India first, but will expand to more countries in the coming months. [272]

Chronology of the logo

First generation (2005–2017)

-

February 2005

-

October 2006

-

December 1, 2011

-

December 19, 2013

-

October 17, 2015

Second generation (2017–present)

-

August 29, 2017

-

October 22, 2024

Internationalization

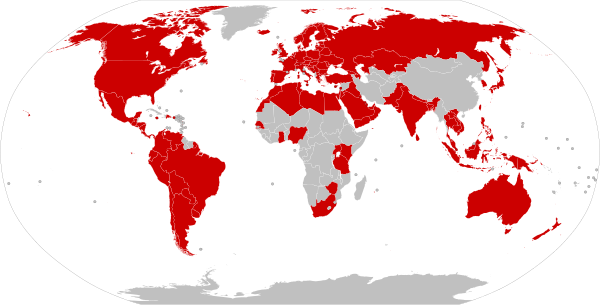

On June 19, 2007, Google CEO Eric Schmidt was in Paris to launch the new localization system.[273] The interface of the website is available with localized versions in 109 countries and regions, two territories (Hong Kong & Puerto Rico) and a worldwide version.[274]

If YouTube is unable to identify a specific country or region according to the IP address, the default location is the United States (Worldwide version). However, YouTube offers language and content preferences for all accessible countries, regions, and languages.[275]

As of 2024, YouTube continues to extend the availability of its localized version to additional countries and regions.[276]

| ||||

| Country | Language(s) | Launch date | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | February 14, 2005[273] | First location and worldwide launch | ||

| Portuguese | June 19, 2007[273] | First international location, first location in South America, and the first Latin American Country. | ||

| French and Basque | June 19, 2007[273] | First European Union location, and the first location in Europe. | ||

| English | June 19, 2007[273] | |||

| Italian | June 19, 2007[273] | |||

| Japanese | June 19, 2007[273] | First Asian location | ||

| Dutch | June 19, 2007[273] | |||

| Polish | June 19, 2007[273] | First location in a Slavic country. | ||

| Spanish, Galician, Catalan, and Basque | June 19, 2007[273] | |||

| English | June 19, 2007[273] | |||

| Spanish | October 11, 2007[277] | |||

| Chinese and English | October 17, 2007[278] | Blocked in Mainland China, Macau uses either US or HK version | ||

| Chinese | October 18, 2007[279] | |||

| English | October 22, 2007[280] | First location in Oceania. | ||

| English | October 22, 2007[280] | |||

| French and English | November 6, 2007[281] | |||

| German | November 8, 2007[282] | |||

| Russian | November 13, 2007[283] | Advertising, monetization, as well as payment and subscription-based services are currently suspended as of March 2022.[284] | ||

| Korean | January 23, 2008[285] | |||

| Hindi, Bengali, English, Gujarati, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu | May 7, 2008[286] | First South Asian location | ||

| Hebrew | September 16, 2008 | First Middle East location | ||

| Czech | October 9, 2008[287] | |||

| Swedish | October 22, 2008[288] | First Scandinavian Country. | ||

| Afrikaans, Zulu, and English | May 17, 2010[273] | First African location. YouTube now has accessible versions in all continents except for Antarctica. | ||

| Spanish | September 8, 2010[289] | |||

| French and Arabic | March 9, 2011[290] | One of the first Arab World locations | ||

| Arabic | March 9, 2011[290] | |||

| Arabic | March 9, 2011[290] | |||

| French and Arabic | March 9, 2011[290] | |||

| Arabic | March 9, 2011[290] | |||

| French and Arabic | March 9, 2011[290] | |||

| Arabic | March 9, 2011[290] | |||

| Swahili and English | September 1, 2011[291] | |||

| Filipino and English | October 13, 2011[292] | First Southeast Asian location | ||

| English, Malay, Chinese, and Tamil | October 20, 2011[293] | |||

| French, Dutch, and German | November 16, 2011[273] | |||

| Spanish | November 30, 2011[294] | |||

| English | December 2, 2011[295] | |||

| English | December 7, 2011[296] | |||

| Spanish | January 20, 2012[297] | |||

| Hungarian | February 29, 2012[298] | |||

| Malay and English | March 22, 2012[299] | |||

| Spanish | March 25, 2012[300] | |||

| Arabic and English | April 1, 2012[301] | |||

| Greek | May 1, 2012 | First location in the Balkans | ||

| Indonesian and English | May 17, 2012[302] | |||

| English | June 5, 2012[303] | |||

| French and English | July 4, 2012[304] | |||

| Turkish | October 1, 2012[305] | |||

| Ukrainian | December 13, 2012[306] | |||

| Danish | February 1, 2013[307] | |||

| Finnish and Swedish | February 1, 2013[308] | |||

| Norwegian | February 1, 2013[309] | |||

| German, French, and Italian | March 29, 2013[310] | |||

| German | March 29, 2013[311] | |||

| Romanian | April 18, 2013[312] | |||

| Portuguese | April 25, 2013[313] | |||

| Slovak | April 25, 2013[314] | |||

| Arabic | August 16, 2013[315] | Multiple Middle East locations launched | ||

| Arabic | August 16, 2013[315] | |||

| Arabic | August 16, 2013[315] | |||

| Arabic | August 16, 2013[315] | |||

| Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian | March 17, 2014 | Multiple European locations launched | ||

| Bulgarian | March 17, 2014[316] | |||

| Croatian | March 17, 2014[317] | |||

| Estonian | March 17, 2014[318] | |||

| Latvian | March 17, 2014[319] | |||

| Lithuanian | March 17, 2014 | Baltic area fully locally accessible | ||

| Macedonian, Serbian, and Turkish | March 17, 2014 | |||

| Serbian and Croatian | March 17, 2014 | |||

| Serbian | March 17, 2014 | |||

| Slovenian | March 17, 2014[320] | |||

| Thai | April 1, 2014[321] | |||

| Arabic | May 1, 2014[315] | |||

| Spanish and English | August 23, 2014 | Used US version before launch. First and only location in a U.S. territory. | ||

| Icelandic | ?, 2014 | |||

| French and German | ?, 2014 | |||

| Vietnamese | October 1, 2014 | First contemporary communist location | ||

| Arabic | February 1, 2015 | Blocked in 2010; unblocked in 2011. | ||

| Swahili and English | June 2, 2015 | |||

| English | June 2, 2015 | |||

| Azerbaijani | October 12, 2015[322] | First location in the Caucasus. | ||

| Russian and Belarusian | October 12, 2015[322] | Monetization services are currently suspended as of December 2024. | ||

| Georgian | October 12, 2015[322] | |||

| Kazakh and Russian | October 12, 2015[322] | First and only location in Central Asia | ||

| Arabic | November 9, 2015[citation needed] | |||

| Nepali | January 12, 2016[323] | |||

| Urdu and English | January 12, 2016[324] | Blocked in 2012; unblocked in 2015. | ||

| Sinhala and Tamil | January 12, 2016[323] | |||

| English | August 4, 2016[citation needed] | |||

| English | June 24, 2018 | |||

| Spanish | January 30, 2019 | Multiple Latin American locations launched. | ||

| Spanish | January 30, 2019 | |||

| Spanish | January 30, 2019 | |||

| Spanish | January 30, 2019 | |||

| Spanish | January 30, 2019 | |||

| Spanish | January 30, 2019 | |||

| Spanish | January 30, 2019 | |||

| Spanish | January 30, 2019 | |||

| Spanish | January 30, 2019 | |||

| Spanish | February 21, 2019 | |||

| Spanish | February 21, 2019 | |||

| Greek and Turkish | March 13, 2019 | Last European Union location | ||

| German | March 13, 2019 | |||

| Spanish | March 10, 2020 | Last Latin American location | ||

| English | June 10, 2020 | Last Oceania location | ||

| Bengali and English | September 2, 2020 | Last location in South Asia | ||

| Khmer | August 25, 2022 | |||

| Lao | August 25, 2022 | Last location in both Asia and Southeast Asia | ||

| Romanian and Russian | March 26, 2024 | Last global location and last European location | ||

On October 17, 2007, it was announced that a Hong Kong version had been launched. At the time, YouTube's Steve Chen said that its next target would be Taiwan.[325][326]

YouTube was blocked from Mainland China from October 18 due to the censorship of the Taiwanese flag.[327] URLs to YouTube were redirected to China's own search engine, Baidu. It was subsequently unblocked on October 31.[328]

The YouTube interface suggests which local version should be chosen on the basis of the IP address of the user. In some cases, the message "This video is not available in your country" may appear because of copyright restrictions or inappropriate content.[329] The interface of the YouTube website is available in 76 language versions, including Amharic, Albanian, Armenian, Burmese, Kyrgyz, Mongolian, Persian and Uzbek, whose countries do not have local channel versions.[330] Access to YouTube was blocked in Turkey between 2008 and 2010, following controversy over the posting of videos deemed insulting to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and some material offensive to Muslims.[331][332] In October 2012, a local version of YouTube was launched in Turkey, with the domain youtube.com.tr. The local version is subject to the content regulations found in Turkish law.[333] In March 2009, a dispute between YouTube and the British royalty collection agency PRS for Music led to premium music videos being blocked for YouTube users in the United Kingdom. The removal of videos posted by the major record companies occurred after failure to reach agreement on a licensing deal. The dispute was resolved in September 2009.[334] In April 2009, a similar dispute led to the removal of premium music videos for users in Germany.[335]

Business model, advertising, and profits

Before being purchased by Google, YouTube declared that its business model was advertisement-based, making 15 million dollars per month.

Google did not provide detailed figures for YouTube's running costs, and YouTube's revenues in 2007 were noted as "not material" in a regulatory filing.[336] In June 2008, a Forbes magazine article projected the 2008 revenue at $200 million, noting progress in advertising sales.[337]

Some industry commentators have speculated that YouTube's running costs (specifically the network bandwidth required) might be as high as 5 to 6 million dollars per month,[338] thereby fuelling criticisms that the company, like many Internet startups, did not have a viably implemented business model. Advertisements were launched on the site beginning in March 2006. In April, YouTube started using Google AdSense.[339] YouTube subsequently stopped using AdSense but has resumed in local regions.

Advertising is YouTube's central mechanism for gaining revenue. This issue has also been taken up in scientific analysis. Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams argue in their book Wikinomics that YouTube is an example for an economy that is based on mass collaboration and makes use of the Internet.

- "Whether your business is closer to Boeing or P&G, or more like YouTube or flickr, there are vast pools of external talent that you can tap with the right approach. Companies that adopt these models can drive important changes in their industries and rewrite the rules of competition"[340]: 270 "new business models for open content will not come from traditional media establishments, but from companies such as Google, Yahoo, and YouTube. This new generation of companies is not burned by the legacies that inhibit the publishing incumbents, so they can be much more agile in responding to customer demands. More important, they understand that you don't need to control the quantity and destiny of bits if they can provide compelling venues in which people build communities around sharing and remixing content. Free content is just the lure on which they layer revenue from advertising and premium services".[340]: 271sq

Tapscott and Williams argue that it is important for new media companies to find ways to make a profit with the help of peer-produced content. The new Internet economy, (that they term Wikinomics) would be based on the principles of "openness, peering, sharing, and acting globally". Companies could make use of these principles in order to gain profit with the help of Web 2.0 applications: "Companies can design and assemble products with their customers, and in some cases customers can do the majority of the value creation".[340]: 289sq Tapscott and Williams argue that the outcome will be an economic democracy.

There are other views[by whom?] in the debate that agree with Tapscott and Williams that it is increasingly based on harnessing open source content, networking, sharing, and peering, but they argue that the result is not an economic democracy, but a subtle form and deepening of exploitation, in which labour costs are reduced by Internet-based global outsourcing.[citation needed]

The second view is e.g. taken by Christian Fuchs in his book "Internet and Society". He argues that YouTube is an example of a business model that is based on combining the gift with the commodity. The first is free, the second yields profit. The novel aspect of this business strategy is that it combines what seems at first to be different, the gift and the commodity. YouTube would give free access to its users, the more users, the more profit it can potentially make because it can in principle increase advertisement rates and will gain further interest of advertisers.[341] YouTube would sell its audience that it gains by free access to its advertising customers.[341]: 181

- "Commodified Internet spaces are always profit-oriented, but the goods they provide are not necessarily exchange-value and market-oriented; in some cases (such as Google, Yahoo, MySpace, YouTube, Netscape), free goods or platforms are provided as gifts in order to drive up the number of users so that high advertisement rates can be charged in order to achieve profit."[341]: 181

In June 2009, BusinessWeek reported that, according to San Francisco-based IT consulting company RampRate, YouTube was far closer to profitability than previous reports, including the April 2009, projection by investment bank Credit Suisse estimating YouTube would lose as much as $470 million in 2009.[342] RampRate's report pegged that number at no more than $174 million.[343]

In May 2013, YouTube launched a pilot program to begin offering some content providers the ability to charge $0.99 per month or more for certain channels, but the vast majority of its videos would remain free to view.[344][345]

See also

- Social impact of YouTube

- YouTube Awards

- YouTube Comedy Week

- YouTube Original Channel Initiative

- List of most-subscribed YouTube channels

- History of podcasting

- History of television

Notes

- ^ Whether YouTube means the original upload date or the first publishing date of videos which were later made unlisted is unclear. The latter likely applies, as that date is indicated on the watch page after initial publication.

References

- ^ "Youtube.com Traffic, Demographics and Competitors". www.alexa.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ Loke Hale, James (May 7, 2019). "More Than 500 Hours Of Content Are Now Being Uploaded To YouTube Every Minute". TubeFilter. Los Angeles, CA. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Alexander, Julia (May 10, 2018). "The Yellow $: a comprehensive history of demonetization and YouTube's war with creators". Polygon. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Wong, Julia Carrie; Levin, Sam (January 25, 2019). "YouTube vows to recommend fewer conspiracy theory videos". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on December 21, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Orphanides, K. G. (March 23, 2018). "Children's YouTube is still churning out blood, suicide and cannibalism". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Orphanides, K. G. (February 20, 2019). "On YouTube, a network of paedophiles is hiding in plain sight". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ (TeamYouTube), Hazel (February 3, 2020). "Heads up, discontinuing older version of YouTube on desktop soon". YouTube Help. Google Inc. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

- ^ "YouTube on May 7, 2005". Wayback Machine. May 7, 2005. Archived from the original on May 7, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ Graham, Jefferson (November 21, 2005). "Video websites pop up, invite postings". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ^ Wooster, Patricia (2014). YouTube founders Steve Chen, Chad Hurley, and Jawed Karim. Lerner Publishing. ISBN 978-1467724821. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ Sara Kehaulani Goo (October 7, 2006). "Ready for Its Close-Up". Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- ^ Dredge, Stuart (March 16, 2016). "YouTube was meant to be a video-dating website". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ "The history of YouTube". Phrasee. May 9, 2016. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Burgess, Jean; Green, Joshua (2013). YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7456-5889-6.[page needed]

- ^ Alleyne, Richard (July 31, 2008). "YouTube: Overnight success has sparked a backlash". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Jawed Karim and Yakov Lapitsky (April 23, 2005). "Me at the Zoo" (Video). YouTube. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- ^ a b Owings, L. (2017). YouTube. Checkerboard Library.

- ^ "YouTube – Your Digital Video Repository". Archived from the original on June 14, 2005. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- ^ Woolley, Scott (March 3, 2006). "Raw and Random". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ^ "Sequoia's Investment Memo on YouTube". Thornbury Bristol. June 11, 2016. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ "YouTube – Baby Fart". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 18, 2005. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ "YouTube – Nintendo Show". YouTube. June 17, 2005. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ a b "YouTube | History, Founders, & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on April 19, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ "YouTube is the Fastest Growing Website", Gavin O'malley, Advertising Age, July 21, 2006.

- ^ a b "YouTube serves up 100 million videos a day online". USA Today. Reuters. July 16, 2006. Archived from the original on December 31, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- ^ "Info for YouTube.com". Alexa.com. July 26, 2006. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- ^ "YouTube U.S. Web Traffic Grows 17 Percent Week Over Week, According to Nielsen Netratings" (PDF). Netratings, Inc. Nielsen Media Research. July 21, 2006. Archived from the original (Press Release) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ^ James Massola (October 17, 2006). "Google pays the price to capture online video zeitgeist". Eureka Street. Vol. 16, no. 15. Jesuit Communications Australia. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2006.

- ^ "Online Video: The Market Is Hot, but Business Models Are Fuzzy". Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "YouTube expands types of advertising". NBC News. August 22, 2006. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c Morrissey, Brian (August 22, 2006). "YouTube Shuns Pre-Roll Video Advertising". Adweek. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Jackson, Nicholas (August 3, 2011). "Infographic: The History of Video Advertising on YouTube". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Google closes $A2b YouTube deal". The Age. Melbourne. Reuters. November 14, 2006. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ "Infographic: YouTube Beats Cable TV in Ad Revenue". Statista Infographics. February 4, 2020. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ La Monica, Paul R. (October 9, 2006). "Google to buy YouTube for $1.65 billion". CNNMoney. CNN. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2006.

- ^ "The History of Viral Videos". Business 2 Community. August 7, 2014. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ Schonfeld, Erick (March 18, 2010). "Chad Hurley's Take From The Sale Of YouTube: $334 Million". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on November 26, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Stafford, Alan (May 31, 2006). "The 100 Best Products of 2006". PC World. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ^ "GooTube: Google buys YouTube". Boing Boing. October 9, 2006. Archived from the original on March 19, 2007. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- ^ Carter, Lewis (April 7, 2008). "Web could collapse as video demand soars". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- ^ "YouTube in 2006 timeline | Web Design Museum". Web Design Museum. February 16, 2018. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ "YouTube in 2007 timeline | Web Design Museum". Web Design Museum. February 16, 2018. Archived from the original on May 30, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ Sample channel page archive from April 20th, 2007

- ^ Coyle, Jake (March 20, 2007). "YouTube announces awards to recognize best user-created videos of the year". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ "YouTube – Broadcast Yourself". January 13, 2006. Archived from the original on January 13, 2006. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

Holiday Video Contest

- ^ "Holiday Video Contest – YouTube – Broadcast Yourself". YouTube. December 19, 2005. Archived from the original on December 19, 2005. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "Most recent" feed (twenty videos per page) in April 2007: Last video on first page uploaded eleven minutes ago.

- ^ "Watch on Mobile – YouTube – Broadcast Yourself". YouTube. April 8, 2007. Archived from the original on April 8, 2007. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "YouTube Mobile A Bust! (Getting 3GP/RTSP to work on WM5)". Chris Duke. June 23, 2007. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "Verizon Wireless Customers First To Upload Videos To YouTube Using Multimedia Messaging". www.verizon.com. July 24, 2007. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Gough, Paul (July 25, 2007). "CNN's YouTube debate draws impressive ratings". Reuters. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- ^ "Part I: CNN/YouTube Republican presidential debate transcript - CNN.com". CNN. November 28, 2007. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "YouTube Partner Program overview & eligibility". YouTube Help. Archived from the original on September 16, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Difference Between YouTube and YouTu.be URLs". February 2, 2019. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ Wayback Machine capture of "youtu.be" dated 20070129040306. Not directly linkable due to the URL blacklist prohibiting URL shortening.

- ^ van Zanten, Boris Veldhuijzen (February 10, 2008). "'Warp' through YouTube with Visual Browser". The Next Web. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ DaveWeLike (June 4, 2008). "Youtube Annotations". StuffWeLike. Archived from the original on August 7, 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ "New on YouTube: Collaborative Annotations". ReadWrite. February 20, 2009. Archived from the original on July 27, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Eves, Derral (February 6, 2013). "How To Create YouTube Video Annotations". DerralEves.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ "Link To The Best Parts In Your Videos". YouTube company blog. October 30, 2008. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ Chacksfield, Marc (October 9, 2008). "YouTube gets new video features | News | TechRadar". TechRadar.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014.

- ^ "Slow YouTube? Try Feather, Made for India". Gtricks. December 7, 2009. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ "Google Testing Comment Search On YouTube". Search Engine Land. October 16, 2009. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ Brad Stone and Brooks Barnes (November 10, 2008). "MGM to Post Full Films on YouTube". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- ^ Staci D. Kramer (April 30, 2009). "It's Official: Disney Joins News Corp., NBCU In Hulu; Deal Includes Some Cable Nets". paidContent. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- ^ "Complete List of 2008 Peabody Award Winners". Peabody Awards, University of Georgia. April 1, 2009. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2009.

- ^ Ho, Rodney (April 2, 2009). "Peabody honors CNN, TMC". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ Chris Soghoian (March 2, 2009). "Is the White House changing its YouTube tune?". CNET. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ "YouTube's Guide to Video Embedding for the U.S. Federal Government Overview". [dead link]

- ^ "Embed YouTube videos without cookies". Axbom • Digital Compassion. August 5, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ^ "Embed videos & playlists - YouTube Help". Archived from the original on July 8, 2024.

- ^ Allen, Kati (November 19, 2009). "YouTube launches UK TV section with more than 60 partners". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2009.