History of Shinto

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

This article contains translated text and the factual accuracy of the translation should be checked by someone fluent in Japanese and English. (February 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Shinto |

|---|

|

Shinto is a religion native to Japan with a centuries'-long history tied to various influences in origin.[1]

Although historians debate[citation needed] the point at which it is suitable to begin referring to Shinto as a distinct religion, kami veneration has been traced back to Japan's Yayoi period (300 BC to AD 300). Buddhism entered Japan at the end of the Kofun period (AD 300 to 538) and spread rapidly. Religious syncretization made kami worship and Buddhism functionally inseparable, a process called shinbutsu-shūgō. The kami came to be viewed as part of Buddhist cosmology and were increasingly depicted anthropomorphically[citation needed]. The earliest written tradition regarding kami worship was recorded in the 8th-century Kojiki and Nihon Shoki. In ensuing centuries, shinbutsu-shūgō was adopted by Japan's Imperial household. During the Meiji era (1868 to 1912), Japan's nationalist leadership expelled Buddhist influence from kami worship and formed State Shinto, which some historians regard as the origin of Shinto as a distinct religion. Shrines came under growing government influence and citizens were encouraged to worship the emperor as a kami. With the formation of the Japanese Empire in the early 20th century, Shinto was exported to other areas of East Asia. Following Japan's defeat in World War II, Shinto was formally separated from the state.

Even among experts, there are no settled theories on what Shinto is or how far it should be included, and there are no settled theories on where the history of Shinto begins. The Shinto scholar Okada Chuangji says that the "origin" of Shinto was completed from the Yayoi period to the Kofun period, but as for the timing of the establishment of a systematic Shinto, he says that it is not clear.

There are four main theories.[2]

- The theory that it was established in the 7th century with the Ritsuryo system (Okada Souji et al.)

- The theory that the awareness of "Shinto" was born and established at the Imperial Court in the 8th-9th century (Masao Takatori et al.)

- The theory that Shinto permeated the provinces during the 11th and 12th centuries (Inoue Kanji et al.)

- The theory that Yoshida Shinto was founded in the 15th century (Toshio Kuroda et al.)

Overview

[edit]Although there is no definitive theory on the origin of Shinto as a religion; its origins date back to the ancient history of Japan. Based on rice cultivation introduced at the end of the Jōmon period and at the start of the Yayoi period, nature worship, which views nature as one with some god, arose in the Japanese archipelago[citation needed]. These beliefs were spread throughout the archipelago as a national festival by the Yamato Kingship in the Kofun era. Rituals were held at the first Shinto shrines such as Munakata Taisha and Ōmiwa Shrine, and the prototype of Shinto was formed. In the Asuka period, the ritual system, shrines, and ceremonies were developed along with the establishment of the Ritsuryo, and the Ritsuryo rituals were formed with the involvement of the Diviners as the administrative body. Ritsuryo rituals were formed in which the Department of Divinities The Tang dynasty rituals were used as a reference for the regulations of the management and operation of rituals in the ritual system. In the following Nara period, the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki were compiled as Japanese mythology along with the national history, and the rituals and the Emperor's family were connected. In the Heian period, the Ritsuryo system was relaxed and the emperor and his vassals became directly involved in the rituals of local shrines without going through the Shinto priests. In addition to this, Shinbutsu-shūgō, a phenomenon of Shinbutsu-shūgō, in which Buddhism was fused with this belief in gods, also occurred in ancient Japan[citation needed], while the idea of Shinbutsu segregation, in which rituals were distinct from Buddhism, was also seen. In addition, beliefs such as Shugendo and Onmyōdō were established in Japan, and these also influenced Shinto.

In the Middle Ages, there was a widespread movement to doctrinize and internalize Shinto[citation needed]. In the Kamakura period, the Kamakura shogunate's veneration protected shrines in various regions, and among the common people, Kumano, Hachiman, Inari, Ise, and Tenjin came to be widely worshipped across regions. In the midst of this spread of Shinto, the intellectual class began to use Buddhist theories to interpret Shinto, starting with the Esoteric Buddhist monk's dualistic Shinto, and advocated such theories as Honji Suijaku theory, which held that the Shinto gods were incarnations of Buddha. In response to this, the Shinto shrines, feeling threatened, systematized the inverted Honji Suijaku theory, which placed their gods above Buddha, against the backdrop of the rise of Shinto after the victory over the Mongol invaders, and established Ise Shinto, which uses the Five Books of Shinto as its basic scripture. In addition, Yoshida Kanetomo, who lost many ancient books in the Ōnin War of the Muromachi period, took the opportunity to forge sutras to create the first Shinto theory that had its own doctrine, sutras, and rituals independent of Buddhism. Yoshida Kanetomo took this opportunity to create the first Shinto theory, Yoshida Shintō, which was the first Shinto theory to have a doctrine, scripture, and rituals. From the Sengoku era to the Azuchi-Momoyama period, Yoshida Shinto was involved in the construction of shrines that enshrined warring feudal lords as gods.

In the Edo period, which constitutes a large part of the Early modern period in Japan, the Tokugawa shogunate reorganized the administration of shrines. On the other hand, Buddhism, which had attained the status of a state religion, was in a period of stagnation as an ideology. In this context, in the early Edo period, mainstream Shinto, from the standpoint of criticism of Buddhism, became increasingly associated with the Confucianism of the Cheng-Zhu school, and shifted to Confucian Shinto such as Taruka Shinto. In the mid-Edo period, Kokugaku, which integrated Shinto with the empirical study of Japanese classics such as poetry and languages, developed and flourished, replacing Confucian Shinto[citation needed]. The Kokugaku scholar Motoori Norinaga strongly criticized the interpretation of Shinto in terms of Chinese-derived Buddhist and Confucian doctrines, and insisted on conducting empirical studies of Shinto scriptures. In the late Edo period, Nobunaga's theology was critically inherited by Fukko Shinto. Fukko Shinto, influenced by Christianity, emphasized the afterlife, as well as Chinese mythology, Hindu mythology, Christian mythology, and other myths from around the world were claimed to be accents of Japanese mythology, and were involved in the subsequent restoration of the monarchy. On the other hand, in the Mito Domain, the Late Mito Studies, which integrated Confucian ethics such as loyalty, filial piety, and humanity with national studies, was developed in response to the criticism of Nobunaga, who rejected Confucianism. Late Mito studies, which advocated the rule of Japan by the emperor by combining Confucianism and Shinto, became the nursery ground for the ideas of the Shishi at the end of the Edo period.

When the Shogunate was overthrown and Japan began to move toward the Late modern period, the new government set the goal of unity of Shinto and politics through the Great Decree of Restoration of the Monarchy. In addition to the propagation of Shinto based on the Daikyo Declaration[citation needed], the Shinbutsu bunri led to the separation of Shinto and Buddhism, and in some cases, the Haibutsu Kishaku, the destruction of temples and Buddhist statues. The Meiji government then formed the State Shinto system in which the state controlled shrines as state religious services. Later, when the Separation of church and state led to the expulsion of the ritualists, the theory of non-religious shrines was adopted, which gave shrines a public character by defining them as not being religions, and local shrines were separated from public spending. In response to this, Priests organized the National Association of Priests and launched a movement to restore the power of the Shinto priests, demanding that the government make public expenditures. The Kannushi organized the National Association of Shinto Priests and launched a movement to restore the Shinto officialdom, demanding that the government make public expenditures. After the end of World War II, the Shinto Directive by the GHQ dismantled the state Shinto system, which was considered the root of Nationalism ideology. The Shinto Directive by the State Shinto of the Shinto Directive dismantled the state Shinto system, and shrines were transformed into religious corporations with the Association of Shinto Shrines as the umbrella organization. Although shrines thus lost their official position in modern times, some shrines have since achieved economic prosperity through free religious activities, and Shinto plays a certain role in Japan's annual events and life rituals.

Ancient times

[edit]Pre-Ritsuryō Rituals

[edit]As rice cultivation spread through the Japanese archipelago from the late Jomon into the Yayoi period, a type of nature worship based on the cultivation of rice also arose. This belief was based on the idea that nature and the kami were one, and that sacrifices and rituals prevented the kami from ravishing the land in the form of natural disasters.[3]

In the Yayoi period, several Shinto practices appeared that had clear similarities to those seen in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki. Archeological finds supporting this include finds believed to be in a similar vein as shrines, such as a new style of square-shaped burial mounds (方形周溝墓, [hōkei shūkōbо] Error: {{nihongo}}: transliteration text not Latin script (pos 13) (help)), bronze ritualistic items from archeological sites including the Kōjindani Site, and large buildings with freestanding roof pillars (独立棟持柱, dokuritsu munamochi-bashira), an architectural feature in common with later shrines, an example of which is seen at the Ikegami-Sone Site. Charred bones of deer and other animals used for divination have also been found in the vicinity of such sites, as well as grave goods such as mirrors, swords, and beads.[4]

Around the 3rd century, what would become the Makimuku ruins began to develop in the Yamato Province near Mount Miwa, and early, large-scale zenpokoenfun began to emerge as well, such as the Hashihaka kofun. It is believed the Yamato Kingship was established in this period. The 3rd century is also the estimated time of creation of the triangular-rimmed shinjūkyō passed down by the Kagami-tsukurinimasu Amateru-mitama Jinja (鏡作坐天照御魂神社) shrine as well as the iron sword excavated at Isonokami Shrine. These objects resemble the holy sword and mirror described in the Kojiki and Nihon Shiki, and allowed for a clearer understanding of elements that would lead to the Shinto faith later.[5]

The first state Shinto rituals occurred in the 4th century. Large numbers of religious artifacts such as bronze mirrors and iron weapons with similarities to the kofun grave goods of the late 4th century in the Yamato region have been excavated from Munakata Taisha on Okinoshima in Munakata, Fukuoka. This indicates that Yamato Kingship rituals began on Okinoshima prior to this.[6] Ritual objects such as small bronze mirrors have also been excavated at Mount Miwa which match those at Munakata Taisha, which lends credibility to the theory that rituals at Mount Miwa (home later to the Ōmiwa Shrine) began at approximately the same time as those on Okinoshima.[7] It is believed that the 4th century, with the rituals held at the early shrines of Munaka Taisha and Ōmiwa Shrine, was when the base of the following Shinto faith developed.[8]

The 5th century sees the spread sekisei mozōhin (石製模造品, small pieces of stone shaped like larger objects such as tools) across Japan. These were originally used in rituals in the Yamato region, and their spread suggests the Yamato Kingship expanded across the Japanese archipelago.[9] Of particular note are the many sekisei mozо̄hin of haji pottery, takatsuki tables, and magatama beads discovered on the eastern side of the country at the Miyanaka Jōri Site Ōfunatsu of Kashima, Ibaraki or the Odaki Ryōgenji Site in Minamibōsō, Chiba, which indicates Yamato Kingship rituals were taking place in these locations.[10] It is believed the Imperial Court later valued the rituals in these regions which led to the establishment of the Kashima Shrine and Awa Shrine with defined holy precincts (神郡, shingun).[11]

Other religious objects of the 5th century include iron grave goods in kofun, as well as sue pottery and cloth excavated from various sites including the Senzokudai Site in Chiba Prefecture and Shussaku Site in Ehime Prefecture, and, therefore, this era is believed to be when the precursors of modern Shinto religious offerings (幣帛, heihaku) developed.[12]

The 6th century brings changes in kofun funerary rituals and a shift from vertical stone burial chambers to horizontal. The exact nature of these kofun funerary rituals was determined by researching haniwa clay figures depcting people using weapons or tools, gifted animals, and nobles riding horses. These figures give a concrete view at these rituals.[13] The shift from vertical to horizontal stone burial chambers suggests the development of beliefs about the nature of the soul in which the soul leaves the body after death. This can be seen in myths in the Kojiki and Nihon Shiki and is believed to have had an impact on the formation of belief in kami with humanlike aspects.[13]

Formation of Ritsuryō Rituals

[edit]

In the 7th century, the establishment of the Ritsuryō system began primarily during the Tenmu period and Jitō period, during which Shinto underwent a major transformation. The systemization of Shinto and the development of an institutional framework of its rituals progressed based on the faiths formed from the Kofun period onward while incorporating aspects from external beliefs, as ritual systems, shrines, and ceremonies developed.

The public ritual system of the ritsuryō state was developed in accordance with the Jingi Ryō (神祇令, lit. "Code of the Kami"). It is believed the Jingo Ryō was established at the same stage as the Asuka Kiyomihara Code and that codes from the Tang dynasty were used as reference.[14] While the regulations for the management and administration of the rituals did follow in accordance with this code, the nature of the rituals was almost entirely unique to Japan, meaning the Jingi Ryō can be thought of as a reformation of Japan-specific religious beliefs based on the Tang code.[15]

The Jingi Ryō established the Department of Divinities, the administrative department for overseeing rituals, as well as the director position the jingi-haku (神祇伯). It was under this jingi-haku that 13 types of rituals were established as state rituals and regulated to occur in accordance with the seasons. These were the Kinen-sai, Chinka-Sai (鎮花祭), Kanmiso-no-Matsuri (神衣祭), Saikusa-no-Matsuri (三枝祭), Ōimi-no-Matsuri (大忌祭), Tatsuta Matsuri (龍田祭), Hoshizume-no-Matsuri (鎮火祭), Michiae-no-Matsuri (道饗祭), Tsukinami-no-Matsuri (月次祭), Kannamesai Festival, Ainame-no-Matsuri (相嘗祭), Mitamashizume-no-Matsuri (鎮魂祭), and Daijō-sai (Niiname-no-Matsuri).[16] The Kinen-sai held in the second month of the lunar calendar as an advance celebration of good harvest. The Chinka-Sai held in the third month of the lunar calendar as flowers petals scatter is held to send off evil spirits. The Tatsuta Matsuri, a prayer to prevent wind damage from typhoons, and the О̄imi-no-Matsuri, a prayer to prevent water disasters, are both held in the fourth and eleventh months of the lunar calendar. And just as the Niiname-no-Matsuri held in the eleventh month of the lunar calendar was to show gratitude for freshly harvested grain, the Ritsuryō rituals were characterized by a strong link with the harvest, aligning with the change of the seasons to show gratitude for the blessings of nature which were needed for agriculture.[17] Regulations required the purification of a government official, and there are two types of purifications within the Ritsuryō rituals: the araimi (荒忌), and the maimi (真忌).[18] The maimi consists of the official abstaining entirely from their duties to undergo purification as they dedicate themselves to preparing for the ritual. The araimi only requires abstaining from the rokujiki no kinki (六色の禁法, lit. "six types of taboos") while continuing their duties.[18] The six taboos are mourning, visiting the ill, consuming the meat of four-legged mammals, carrying out executions or sentencing criminals, playing music, and coming in contact with impurities. The government officials could be punished if they failed to conform to this requirement. The festivals were divided into major, medium, and minor rituals depending on the length of the time required for the purifications. For example, a major ritual (of which there is only the Daijō-sai) requires an araimi of one month and a maimi of three days.[18]

Out of the several Ritsuryō state rituals, the Kinen-sai, Tsukinami-no-Matsuri, and О̄nie-matsuri included a ritual format unique to Japan called heibu (班幣).[19] This involved the Department of Divinities calling an assembly of priests from every formally recognized shrine in the country, where the Nakatomi clan performed ritual prayers and the Inbe clan distributed religious offerings called heihaku to the priests. The priests took the heihaku to offer to the kami of each of their shrines.[20] There were also regulations for the Ōharae-shiki, in which the Nakatomi clan first offered an ōnusa to the emperor, and the Yamatonoaya clan and Kawachinohumi clan offered a harae-no-tachi (祓刀, sword used for purification) as well as performed the reading of ritual incantations. Then, a large group of male and female court officials gathered at the haraido (祓所, purified ritual location) in the suzakumon where the Nakatomi clan read purification incantations and divinators of the imperial court performed the purification.[21]

Up until this point, many shrines had no actual buildings, but these buildings started to become established in this period, particularly at officially recognized shrines. The shinkai ranking system was also established at this time, and shrines at which miracles occurred were assigned a jinpu (神封) (a shrine equivalent of a fuko (封戸) which established the shrine as a partial tax recipient) and a shinkai rank, and particularly venerated shrines were given a shingun holy precinct.[22] Some shrines also received a type of citizen assigned to the shrine known as kanbe (神戸) as well as shrine-owned farm fields called kanda (神田) in which they worked in order to support the economic requirements of the shrine.[22] Regions without officially-recognized shrines continued without physical shrine buildings. Someone was selected to act as the hafuri (祝), a person in charge of rituals, and they conducted agriculture-related rituals in spring, when the rice was planted, and fall, at harvest, to thank the kami. However, as time went on, government officials began visiting these places where the rituals were held where they informed the locals of the country's laws, adding an official aspect to these rituals, and the establishment of physical shrines spread across the country.

The ritual system of the Ise Grand Shrine was also developed during this period, and, during the reign of Emperor Temmu, the yuki (悠紀) and suki (主基) (regions to provide rice for the emperor's ascension ceremony) were selected through divination, and the emperor would dine with Amaterasu while facing the direction of Ise, which formed the Daijō-sai as it is known in its modern form. The saiō system also came to be in which an unmarried female member of the imperial family was sent to serve at the Ise Grand Shrine, and the practice at the Ise Grand Shrine of shikinen-sengū (式年遷宮) began during the reign of Empress Jitō which is the practice of rebuilding all the shrines buildings at once every approximately 20 years.

Shinto had an influence on the compilation of national history, a duty which was formed during the reign of Emperor Temmu and developed further during the reign of Empress Genmei. The Kojiki and Nihonshiki were compiled during the 8th century and contain Japanese myths in the form of tales from the Age of the Gods, as well as stories of Emperor Jimmu and how he established the country. The compilations were the basis of the imperial family's claim as the rightful rulers.[23] Efforts were made to link ancient rituals to the kami believed to be the progenitor of the imperial family, such as by assuming the kami of Munakata Taisha (the Three Female Deities of Munakata) are the three goddesses birthed by Amaterasu, while the origins of the court ritual clans such as the Nakatomi clan, Inbe clan, and Sarume-no-kimi people were sought after in the world of myth.

The Transformation of Ritsuryō and Heian Rituals

[edit]The Ritsuryō ritual system transformed during the Heian period (794–1185) as the Ritsuryō system was relaxed.

In 798, it became impossible to maintain the heibu system of distributing religious offerings to all shrines in the country, resulting in the shrines being divided into two types: the kanpeisha (官幣社) which continued to receive their religious offerings from the Department of Divinities, and kokuheisha (国幣社) which received began to receive theirs from their provincial government. Shrines were further divided in greater and lesser shrines, as well as some shrines with particularly powerful miraculous powers classified as myōjin taisha (名神大社). These classifications were outlined in the Engishiki Jinmyōchō of 927.[24]

As the imperial court expanded along with the relaxation of the Ritsuryō system, the emperor and their close advisors became directly involved in regular rituals of shrines that had particularly strong connections to the imperial court, rather than the Department of Divinities overseeing this duty, which led to the development of kōsai (公祭, lit. "public festival"), officially recognized and officiated rituals, during the late Nara and early Heian periods. During the reign of Empress Kōken, Empress Kōmyō and others began changing the regular rituals of the many kasuga jinja (春日神社), shrines housing the patron kami of the Fujiwara clan, into kо̄sai rituals.[25] Special rituals also became more common as the emperor's authority grew. These were rituals for specific kami, and in addition to the regular rituals, in which the emperor themself dispatched the imperial representative. The first example of this was the Kamo Rinjisai (賀茂臨時祭, lit. "Kamo special festival") held by Emperor Uda during his reign. The regular festival that developed after this retained the "special" name.[26]

The emperor and their close advisors became directly involved with even more rituals such as the emperor's Maichōgai (毎朝御拝, lit. "every morning worship"), morning prayers sent to Ise Grand Shrine, conducted at a platform within the palace called the Ishibainodan (石灰壇) or the Ichidai-Ichido no Daijinbō-Shi (一代一度の大神宝使), a tradition which began in this period in which a court messenger takes sacred relics to specific shrines at an emperor's ascension.[27] The practice of gyōkō (行幸) first occurred during Emperor Suzaku's reign.[28] Gyо̄kо̄ is the practice of the emperor themself going to a shrine and dispatching the ritual official from there, while up until that point, the emperor would have stayed in the imperial court and dispatched the officials from there.[28]

At this time, the nobles became more interested in ujigami rituals, and we see several collections of traditions written during this time. There is the Kogo Shūi written by Inbe no Hironari which consisted of an orally transmitted history of the Inbe clan and also acted as a counter to the Nakatomi clan. There is also the Sendai Kuji Hongi which contains a collection of histories about the different clans thought to have been compiled by the Mononobe clan, as well as the Shinsen Shōjiroku containing the lineage and histories of the various clans which divided the clans into the branches of divine ancestry, imperial ancestry, foreign ancestry, and those of unknown ancestry.[29]

The Engishiki, containing laws and customs, was completed in 927. Volumes one through ten contain laws regarding Shinto, and these ten volumes are collectively referred to as the Jingishiki (神祇式). The contents of each volume are as follows: One and two, seasonal rituals. Three, special rituals. Four, the Ise Grand Shrine. Five, position at the Ise Grand Shrine. Six, the role of saiin priestesses. Seven, Daijō-sai. Eight, norito. Nine and ten, the upper and lower kami.[30]

In addition, as it was no longer possible to maintain the practice of sending religious offerings to all myōjin taisha shrines, it turned to a practice called kinen kokuhouhei (祈年穀奉幣) which involved making offerings only to the most prominent of these shrines twice a year. This practice expanded to sixteen shrines later, then eventually to twenty-two shrines, and this continued until 1449 (the first year of the Hōtoku era) in the Late Middle Ages.[31]

In regards to local rituals, provincial officials were dispatched and ranked the shrines in that province, developing the Ichinomiya system which ordered the shrines to be worshiped at.[32] These officials noted the shrines that saw worship in a kokunai jinmyōchō (国内神名帳, lit. "domestic shrine register"), and, later, shrines of ninomiya rank or below were grouped together into a sōja shrine.[32]

Synthesis with and Separation from Buddhism

[edit]After the official introduction of Buddhism in the 6th century, Buddhism spread across Japan through the conflict between the Monobe clan and the Soga clan over the adoption of Buddhism. Early on in the adoption, however, Buddhism was not seen as different from Shinto and was taken up in the same way as local Shinto had been. Buddha was called Adashikuni-no-kami (蕃神, lit. "kami of barbarians"), and some women, such as Shima, Datto Shiba's daughter, left home to maintain Buddhist statues similar to what miko did.[33] Later, in the 7th century, the kami were believed to reside in devaloka and thought to be seeking liberation just like humans. Jingū-ji were built within shrines as locations where Buddhist practices could occur such as reading Buddhist scriptures before the kami.[34] An early example of this is the jingū-ji at Tado Shrine founded by the monk Mangan.[34] Buddhist temples also made attempts to move Shinto closer to Buddhism which resulted in the belief that kami were also Defenders of the Justice, beings who protect dharma, and so jinjū-sha shrines were built into Buddhist temples.[35]

Several faiths appeared during the Heian period which contained elements of both Shinto and Buddhism such as belief in Goryō[36] and the Kumano faith which regards Kumano a Pure Land,[37] and the influence of Buddhism led to the creation of statues of kami inspired by Buddhist statues.[38] Shinto-Buddhims syncretism continued as time went on, giving rise to the honji suijaku theory which claims kami are the temporary forms of Buddhist deities manifested in Japan in order to save the people. There were also instances of using Buddhist deity terms such as bosatsu (菩薩, bodhisattva) and gongen when referring to kami, as well as the practice of carving buddhist images, the true forms of the deities, on the backs of mirrors, believed to be the house of the kami. These mirrors were called mishōtai (御正体, lit. "honorable true form") because they depicted the kami's true form.[39]

At the same time, the desire to separate Shinto and Buddhism was seen in the imperial court and amongst the shrines. Regulations such as the Jōgangishiki (貞観儀式) and the Gishiki (儀式) forbade central officials and officials from the Five Provinces from conducting Buddhist services during the period of the Daijō-sai. Buddhist monks and nuns were also forbidden from attending medium rituals or minor rituals that occurred during purification of the imperial palace, and Buddhist services could not be held in the palace.[40] From the middle of the Heian period onwards, the emperor was also required to stop any Buddhist activities during the period of purification for rituals in which the emperor conducts the purification themself, such as for the Niiname-no-Matsuri, Tsukinami-no-Matsuri, and the Kannamesai Festival, and other government officials were also meant to avoid Buddhist practices during this time.[40] At the Ise Grand Shrine, some words were considered taboo. For Buddha (仏, hotoke) they used nakago (中子, lit. "center") and for Buddhist priest (僧侶, sōryo) they used kaminaga (髪長, lit. "long hair"). These indirect terms were even used at the saiō priestess's residence.[40] While Shinto and Buddhism had begun to blend as a faith, ritualistically, they remained two separate systems.

Development of Shugendō and Onmyōdō

[edit]In ancient Japan, mountains were believed to be other worlds, such as the afterlife, and were rarely entered, but they became areas for ascetic practices during the Nara period under the influence of various factors such as esoteric Buddhism, Onmyōdō, and kami worship.[41] One figure in the early stages of this practice was En no Ozunu, and Shugendō was formed as these ascetic mountain practices developed into an organization near the end of the Heian period, with Kinpu Mountain, Kumano Sanzan, the Three Mountains of Dewa, and Mount Togakushi prominent examples of mountains of power.[41] This was followed by the establishment of various Shugendō schools such as the Honzanha (本山派) of the Tendai school, the Tōzanha (当山派) of the Shingon school, the Haguroha (羽黒派) based at the Three Mountains of Dewa, and the Hikosanha (英彦山派) based at Mount Hiko.[41]

Onmyōdō was established during the Heian period by the imperial court. It developed independently in Japan based on influences from the philosophies of yin and yang and wuxing which came over from China.[42] Onmyōdō's development also had an impact on Shinto, as some rituals such as the О̄harae-shiki and Michiae-no-Matsuri (道饗祭) which had been conducted by the Department of Divinities were later conducted by the Onmyōryō (陰陽寮), the department of Onmyōdō. Additionally, the ritual text for the О̄harae-shiki, also known as the Nakatomi Harae (中臣祓), changed into the Nakatomi Saimon (中臣祭文, lit. "Nakatomi ritual text") and became used by Onmyōdō priests.[42] The change was that the original ritual incantation was in the senmyōtai (宣命体) style, in which the words are directed to the ritual's attendees, while the newer incantation was in the sōjōtai (奏上体) style, in which the words are directed to the kami.[42] However, while Shinto rituals were affairs of the state, Onmyōdō rituals were conducted in an environment of heightened materialistic desires of the aristocrats in order to request personal success and the curing of illness.[43] Beginning in the 10th century, the department overseeing Onmyōdō was almost entirely led by successive generations of the Abe and Kamo clans.[44]

Middle Ages

[edit]The Shogunate's Shinto System

[edit]The shrine system went under a reorganization under the shogunate with the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate. Minamoto no Yoritomo, the founder of the shogunate, was a devout follower of Shinto and officially acknowledged the Ise Grand Shrine's claim over its territory. Other particularly venerated shrines were the Izusan Shrine, Hakone Shrine, and Mishima Shrine, and it became custom for future Shoguns to visit Izu Hakone in January every year a practice called Nisho Gongen (二所権現) which may have been the origin of modern-day Hatsumōde.[45] The Magistrate of Temples and Shrines was established in 1194. The Kamakura Shogunate carried on the piety of Minamoto no Yoritomo, as seen in Article 1 of the Goseibai Shikimoku enacted in 1232 which called for the reformation of shrines which should focus solely on carrying out rituals. [46] Additionally, the Kantō Shinsei (関東新制), a legal code released by the shogunate as opposed to the emperor, contained several regulations surrounding religion such as those relating to development of Shinto institutions and the prevention of the misconduct of Shinto priests.[47] Government positions such as the kitō bugyō (祈祷奉行) and shinji bugyō (神事奉行) were established which oversaw religious events rather than the administration of shrines. The Senjū clan began to inherit the kitо̄ bugyо̄ position during the Muromachi period.

The jisha-densō (寺社伝奏) position had been established within the imperial court and was responsible for conveying requests from the shrines to the emperor. However, once the shogunate came into power, this shifted to reporting to the shogun then communicating the shogun's decisions back to the shrines.[47] The retired emperor also conducted more frequent pilgrimages to Kumano Taisha during this period, and the imperial court began to focus more on Shinto rituals as its authority declined as the shogunate rose. Emperor Juntoku wrote in the Kinpishō (禁秘抄), "Shinto matters first, all other matters after."[48]

The People's Faith in the Middle Ages

[edit]The faith of the common people also changed during the Middle Ages. During ancient times, the people's faith centered on rituals worshipping local ujigami to pray for the prosperity of their community. In the Middle Ages, however, kami with mystical power were divided in a process called bunrei and taken to other regions, leading to an increase in shrines called kanjōgata-jinja (勧請型神社) housing these divided kami where people prayed for individual prosperity.[49]

Particularly widely worshipped were Kumano Gongen (熊野権現), Hachiman, Inari Ōkami, and Amaterasu.[50] The region of Kumano was originally believed to be another world where the spirits of the dead went, but the syncretism with Buddhism led to the belief that Kumano was a manifestation of the Pure Land in the real world, with Kumano Gongen at Kumano Hongū Taisha believed to be Amitābha.[51] Many people went on pilgrimages in groups to Kumano to pray to pass on to the next world in death as well as to receive prosperity in this world, so much so that they became known as the "ants' pilgrimage to Kumano" as they resembled a line of ants.[51] Visits by the retired emperor became common during the Insei period as well. Hachiman was brought from Usa Jingū as a divided kami and protector of Emperor Seiwa by Iwashimizu Hachimangū, while also being worshiped as the guardian kami of the Seiwa Genji clan, while Minamoto no Yoshiie also established Tsurugaoka Hachimangū in Kamakura with the divided Hachiman.[52] When Minamoto no Yoritomo established the Kamakura Shogunate, Gokeijin throughout Japan who followed the Kamakura Shogunate also prayed to Hachiman in their own territories, and the Hachiman faith spread throughout the country.[52] Inari was originally the clan deity of the Hata clan, but in the Heian period (794-1185), Inari was revered as the guardian deity of Toji, and was combined with Dakini to spread throughout Japan as a deity of agriculture.[53] In the Fushimi Inari-taisha, the first day of the first month of the lunar year, many common people would come to the shrine to pray. The first day of the first month of the lunar year is the time when the gods of the mountains descend to the villages to become the gods of the rice fields in the Tanokami faith.[53]

Originally, it was forbidden for anyone but the emperor to make religious offerings or give prayers at the Ise Grand Shrine, but it and other shrines lost their financial foundation in the Middle Ages under the Ritsuryō system which led to religious officials from the shrine, mostly oshi (御師), actively gathering contributions and funds for building costs. They did this through proselytizing and conducting private prayers at manors across the country which spread the Ise faith first to lords and the warrior class, then to the common people.[54] The earlier Kumano faith also contributed to the spread of the Ise faith as pilgrims on the Kumano Pilgrimage had to pass through Ise Grand Shrine along the Ise-Ji Route, resulting in many people beginning to worship the kami at Ise Grand Shrine.[55] An account of the rebuilding of the outer shrines of Ise Grand Shrine in 1287 in the Kanchūki (勘仲記) from the Kamakura Period states, “The exact number of the thousands, tens of thousands of worshippers who attended is unknown,” showing the large numbers of common people who traveled to the Ise Grand Shrine.[56]

As worship at a main shrine increased, the kami of those main shrines were divided and brought to various villages[citation needed]. With the rise of the shōen manorial system as well, the kami of shrines of the manorial lords were divided and brought across Japan resulting in a third of all shrines of modern Japan being associated with one of the five faiths of Hachiman, Ise, Tenjin, Inari, or Kumano.[49]

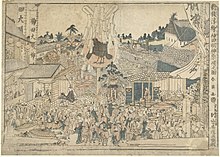

Festivals for the commonfolk also spread within urban areas. The people began to host the Gion Festival every year after 863 when the Imperial Court held an open goryōe (御霊会) at temple of Shinsenen in which the people of the city could participate. During the goryōe, the mikoshi was paraded around town from the ritual welcome of the kami at the beginning of the festival until the return to the shrine at the end which was thought to increase the spiritual power of the kami.[57] The residents of Kyoto prepared the otabisho resting places for the mikoshi as well as prepared for and conducted the rites, meaning the Imperial Court had little involvement in the public aspects, resulting in a public festival with a strong local feel and identity.[57] Other festivals established by the middle of the Heian period were the Kitano Goryōe, Matsuo Festival, Imamiya Festival, and Inari Festival.[58]

Furthermore, as the villages of the manors became more autonomous and as the self-governing communal sō (惣) villages were established, administrative village organizations overseeing faith activities called miyaza (宮座) gained attention as organizers of festivals. The miyaza were led by elders known as otona (オトナ, lit. "adult") or toshiyori (年寄, lit. "elder") while younger members were responsible for conducting the rituals. Shrines became a spiritual center for the villagers as they recited oaths to the kami there when the village made decisions, as well as conducted vow ceremonies (一味神水, ichimijinsui) when forming a group such as an ikki (一揆). The villagers would visit the shrine even during their daily lives as farmers, and the head of the shrine was selected for a year-long term from amongst the villagers.[50]

Development of Shinto Theory and the Honji Suijaku Theory

[edit]A movement spread through the intellectual class to develop a doctrine for and incorporate the religion of Shinto into their ideals. The first attempt was the Ryōbu Shintō (両部神道) Theory developed around the mid-Heian period by esoteric Buddhist monks using esoteric terminology. An early example of this is seen in Shingon Fuhō San'yō-shō (真言付法纂要抄, Collected Essentials on Shingon Dharma) written by Shingon Buddhist monk Seison in the 11th century in which he depicts Amaterasu as the same being as Vairocana and argues Japan is well suited to the spread of esoteric Buddhism. The most important Shinto theories of the Middle Ages were derived from this theory.[59]

Following this, Buddhist monks began to frequent the Ise Great Shrine, including Chōgen in 1186, with many Ryōbu Shintō texts written in monk residences located within the Ise Great Shrine's territory. The Mitsuno-gashiwa Denki (三角柏伝記) and the Nakatomi no Harae Kunge (中臣祓訓解) are believed to be early examples of such texts. These texts place the shrine's Inner Shrine as the Womb Realm and the Outer Shrine as the Diamond Realm of esoteric Buddhism, and both together are seen as a manifestation in this world of a mandala.[60] Additionally, Amaterasu is said to be Brahmā as Surya, while Toyouke-hime is said to be Brahmā as Chandra. The Reikiki (麗気記) was compiled afterwards as a collection of secret theories based in Shingon Buddhism and became a representative text of Ryōbu Shintō.[61]

As Shinto manuscripts and writings were developed at temples, Ryōbu Shintō-style schools were established to pass down the writings, along with the establishment of several other factions including Sanbōin-ryū (三宝院流) founded by Imperial Prince-Monk Shukaku Hosshinō and Miwa-ryū (三輪流) which developed at Byōdō-ji Temple near Mount Miwa.[62] These Ryōbu Shintō schools passed down their secrets while conducting abhisheka and initiations in a similar way to esoteric Buddhism in a practice known as Shinto Abhesheka (神道灌頂, Shintō kanjō).[63]

Shinto theories developed not only from Shingon Buddhism, but also from ideals based on Buddhist-Shinto syncretism from the view of Tiantai Buddhism. The foundation of this was an explanation of the significance of the kami of Hiyoshi Taisha, the guardian kami of Mount Hiei, through the lens of Tendai Buddhist thought. This was called Sannō Shintō.[64]

The Yōtenki (耀天記) was written in the 13th century, and it was said the Buddha manifested as Ōnamuchi of the main shrine, Nishi Hongū, of Hiyoshi Taisha in order to save the people of Japan, a small country in the Degenerate Age of Dharma.[65] Additionally, the monk Gigen (義源) wrote the Sange Yōryakki (山家要略記) in the 14th century in which he asserted not just Ōnamuchi but all kami of Hiyoshi Taisha were manifestations of buddhas.[66] Afterwards, Gigen's disciple, Kōshō (光宗), wrote the Keiran Shūyōshū (渓嵐拾葉集) in which he systemized the doctrine by linking all Tendai Buddhism to Hiyoshi Taisha kami. He also claimed the Hiyoshi Taisha kami innately resided within people's hearts.[67] As the belief of original enlightenment spread, the idea that people are already enlightened regardless of their religious practices, these writings began to claim the kami, as beings more familiar to the Japanese people, were in fact the true form and buddhas were a manifestation of the kami in what was known as the inverted honji suijaku theory (反本地垂迹説, han-honji suijaku).[67] Shinto theory in the Tendai school was primarily developed by a group of monks known as kike (記家, lit. “chroniclers”).[68]

Sansha Takusen (三社託宣) hanging scrolls began to appear in the late Kamakura period in Tōdai-ji or the ancient region of Nara. These were the words of the three kami Amaterasu, Hachiman, and Kasuga Daimyojin, expressing the tenets of honesty, purity, and mercy in kanbun style.[69] These three kami in particular become the object of this worship because it was said they, Amaterasu, the ancestor deity of the imperial family, Hachiman, the patron deity of the samurai class (Seiwa Genji), and Kasuga Daimyojin, the patron deity of the noble class (the Fujiwara clan), entered into a divine pact with each other in the Age of the Gods, resulting in the belief that it was in the Age of the Gods that those three classes were bound to work in coordination as they rule.[70]

As Buddhist-Shinto syncretism spread during the Middle Ages, various shrines began to create engi (縁起), writings and illustrations of religious histories, particularly of the religious institutions themselves. Prominent examples include the Kasuga Gongen Genki-e (春日権現験記絵), the Kita no Tenjin Engi (北野天神縁起), and the Hachiman Gudōkun (八幡愚童訓), as well as the Shintōshū (神道集), a collection of such texts created in the 14th century. It is believed these texts and illustrations were created by the religious institutions in order to receive reliable patronage from the samurai class as the Imperial Court declined at the outset of the Middle Ages.[71] This period also saw the spread of Middle Ages Mythology, a body of Shinto myths reinterpreted through a lens of Buddhist-Shinto syncretism.

The Honji Suijaku theory was incorporated into Shin Buddhism which rapidly grew during the Kamakura period. One Buddhist monk of the school, Zonkaku, authored the Shoshin Honkaishū (諸神本懐集) in which he divided Japan's shrines into gonsha (権社), shrines which housed a manifestation of a buddha, and jissha (実社), shrines which did not, and argued that only the kami of gonsha should be worshipped.[72] Even in the Nichiren school of Buddhism, the monk Nichiren himself actively incorporated Shinto into the school, which his disciple Nichizō systemized into Hokke Shinto.[73] Their belief was that if the true dharma as based on the Lotus Sutra was correctly conducted, then the Thirty Guardian Deities (三十番神, Sanjū Banshin) with Atsuta no Ōkami at their head would protect Japan, each one protecting for a day in a rotation.[74] Other schools to take up the Honji Suijaku theory with varying approaches were the Jishū school, the Rinzai school, and the Sōtō school.[75]

Japan as a Divine Land and the Inverted Honji Suijaku Theory

[edit]As that was occurring within the Buddhist faith, Shinto institutions were also receiving influence from external religions such as Buddhism while movements to create doctrine for and internalize Shinto grew more actively. Inverted honji suijaku theories which placed the kami above buddhas also developed in opposition to the honji suijaku theory. The collapse of the Ritsuryō system produced a sense of crisis amongst the Shinto authorities as the foundation that supported their existence was shaken. Shinto authorities began creating writings for Shinto rituals in an attempt to gain religious authority and claim Shinto's place in resistance to Buddhism as Buddhist authorities were actively closing in on the world of the kami and attempting to reinterpret Shinto using Buddhist theories.[76] Also in the background during the creation of systemized Shinto theory was Japan's victory in the Mongol invasions of Japan which resulted in a belief of Japan as a divine land protected by the kami, a belief which strengthened during this period along with the authority of the Ise Shrine through the increase throughout Japan of jingu mikuriya (神宮御厨), territories belonging to the shrine originally for the production of offerings to the kami.[77]

The first school to do this was Ise Shinto, established in the mid-Kamakura period. Ise Shinto is a school of Shinto established primarily by the Watarai clan who were priests of the Outer Shrine with the Shintō Gobusho (神道五部書, Five Shinto Scriptures) as central texts. Of the five Scriptures, the Yamatohime-no-Mikoto Seiki (倭姫命世記, Chronicle of Yamatohime-no-mikoto) and Zō Ise Nisho Daijingū Hhōki Hongi (造伊勢二所太神宮宝基本記) were created relatively early. They referenced the Womb World-Diamond World theory of Ryōbu Shintō as they placed the Inner and Outer Shrines on the same level, continuing on with plans to place the Outer Shrine in a superior position.[78] These writings identified the kami of the Outer Shrine, Toyouke-hime, to be Ame-no-Minakanushi, one of the original kami, in order to increase her standing compared to Amaterasu, as well as defined the Inner Shrine as the Wuxing agent of Fire and the Outer Shrine as the agent of Water in an attempt to raise the Outer Shrine's standing as Water regulates Fire. The kami Takuhadachiji-hime, mother of Ninigi-no-Mikoto, was also placed as a grandchild of Toyouke-hime, inserting Toyouke-hime into the imperial ancestral line.[79] Other movements in addition to these kami theories included an emphasis on Japan as a divine land through preaching the eternal nature of the imperial line, the dignity of the Three Sacred Treasures, and the honor of the shrines, a spread of reason and morality based on the Two Great Virtues of Shinto, honesty and purity, and a focus on the diligent practice of, cleansing prior to, and purification through Shinto rituals.[80]

Ise Shinto further developed as a result of what is known as the imperial character controversy (皇字論争) which revolved around the addition of the character meaning "divine" or "imperial" (皇) was added to the Outer Shrine's name in 1296. Center of the Outer Shrine at the time Yukitada Watarai referenced the first two of the Shintō Gobusho as evidence of the Outer Shrine's legitimacy, authored the further three of the five, Amaterashimasu Ise Nisho Kōtaijingū Gochinza Shidaiki (天照坐伊勢二所皇太神宮御鎮座次第記), Ise Nisho Kōutaijin Gochinza Denki (伊勢二所皇太神御鎮座伝記), and Toyōke Kōtaijin Gochinza Hongi (豊受皇太神御鎮座本記), then spread those writings of Ise Shinto throughout society.[81]

Ieyuki Watarai followed Yukitada Watarai as center of the Outer Shrine and established Ise Shinto. In addition to penning the Ruijū Jingi Hongen (類聚神祇本源) and systemizing Ise Shinto while references various other writings from Neo-Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, he also presented kizen-ron (機前論), a theory unique to Shinto doctrine. According to this theory, the chaotic state that existed prior to the world's formation was calledkizen (機前), that this kizen was the source of consciousness, as well as the essence of the kami.[82] He further preached maintaining purity was how one utilizes kizen.[83]

Later, Tsuneyoshi Watarai claimed the Inner and Outer Shrines were of equal standing as the Watarai Clan served the Inner Shrine before the Outer Shrine was established and that the view of Toyouke-hime as a kami of Water allowed a comparison of the two kami to the Sun and the Moon. Just as the Sun and the Moon together light the heavens, so do Amaterasu and Toyouke-hime stand together.[77]

At the opening of the Nanboku-chō period, Kitabatake Chikafusa wrote the Jinnō Shōtōki (神皇正統記, "Chronicles of the Authentic Lineages of the Divine Emperors") and the Gengenshū (元元集) while influenced by Ise Shinto in which he noted the imperial line remained unbroken since the Age of Gods and argued Japan was superior due to being a divine land. He also argued the emperor is required to have Confucian virtues and must not abandon the various teachings of religion.[84] It was also during this period that Tendai monk Jihen also received influence from Ise Shinto and wrote Kuji Hongi Genki (旧事本紀玄義) in which he presented a depiction of the emperor as sovereign and established political discourse within Shinto.[85] Court noble Ichijō Kaneyoshi wrote the Nihon Shoki Sanso (日本書紀纂疏) in which he conducts a philosophical analysis of the scrolls on the Age of Gods of the Nihon Shoki, forming Shinto thought. Inobe-no-Masamichi wrote the Jindai Kankuketsu (神代巻口訣) which discussed Shinto theology through commentary of those same scrolls.

Formation of Yoshida Shinto

[edit]

The destruction of Kyoto during the Ōnin War in the Ōnin period affected many temples and shrines and resulted in the cessation of rituals, including the Daijōsai and crowning ceremonies. One Shinto priest most affected by the turmoil was Yoshida Kanemoto. Kanemoto had served at the Yoshida Shrine which was lost in the fires of war, along with tens of lives of the residents living in the area around the shrine. In his turmoil, he fled into the wilds.[86] However, the loss of many ancient texts in the war became an opportunity for new Shinto doctrine to develop in the form of Yoshida Shinto.[87]

The Yoshida family’s original name was Urabe, of the Urabe Clan. As Shinto priests, they specialized in tortoise-shell divination and long inherited the position of Senior Assistant Director of Divinities (神祇大副, Jingi Taifu), the second-highest position in the Department of Divinities. In the Middle Ages, Urabe no Kanekata was an expert of research into Japanese texts, as seen in the Shaku Nihongi (釈日本紀) he authored, earning the Yoshida family the monicker of “House of Japanese Chronicles”.[88]

Kanemoto went on to write the Shintō Taii (神道大意) and the Yuiitsu Shintō Myōhō Yōshū (唯一神道名法要集) in which he compiled Shinto thought from the Middle Ages while incorporating discourse from several other religions in order to present a new Shinto theory in the form of Yoshida Shinto. In his writings, Kanemoto divided Shinto into three varieties: Honjaku-engi Shintō (本迹縁起神道) (the histories passed down by shrines), Ryōbu-shūgō Shintō (両部習合神道), and Gempon-sōgen Shintō (元本宗源神道). He further claimed the Gempon-sōgen Shintō passed down by his own family was the only true Shinto transmitted since the very origin of the country. He also placed the kami as the peak of all things, and Shinto as the origin of all things.[89] In regard to the relationship between Shinto, Confucianism, and Buddhism, he strongly purported a root-leaf-fruit theory which claimed Shinto was the roots, Confucianism was the leaves that grew in China, and Buddhism was the fruit which blossomed in India. This argued that while the three religions were one, Shinto was the true religion.[90]

Additionally, he claimed Shinto had three aspects: the body, its true essence, the appearance, how it manifests, and the purpose, how it affects the world. These three aspects govern the sun and the moon, the warmth and the cold, nature, and all other phenomena. Ultimately, his Shinto theory was a type of pantheism in that he claimed the kami resided within all things in existence, permeating the entire universe.[91] In addition to his theories of Shinto, Kanemoto developed many rituals. He began by building the Daigengū Saijōsho (大元宮斎場所) at Yoshida Shrine. This enshrined the kami of Ise Shrine, the Hasshinden, and the more than 3,000 kami of the Engishiki shrines. He then declared the Daigengū to be the root of all religion in Japan from the time of its founding, as well as the main shrine for all shrines throughout the country.[92] Furthermore, with influence from esoteric Buddhism, he created three rituals known collectively as the Three Dais Rituals (三壇行事, San Dan Gyōji). These included the Eighteen Shinto Rituals (十八神道行事, Jūhachi Shintō Gyōji), the Sōgen Shinto Ritual (宗源神道行事, Sōgen Shintō Gyōji), and a homa ritual which consisted of lighting a fire in the octagonal dais in the center of the hearth then praying as grains and rice porridge were cast into the fire.[93]

These Shinto theories were purported to have been developed based on a collection of three writings known as the Three Sacred Scriptures (三部の神経) which include Tengen Shinpen Shinmyō-kei (天元神変神妙経), Jimoto Jintsū Shinmyō-kei (地元神通神妙経), and Jingen Jinkryoku Shinmyō-kei (人元神力神妙経)人元神力神妙経.[94] These scriptures are said to contain the teachings of Ame-no-Koyane, however, they are considered fictitious as there is no evidence they were ever created.[95] Kanemoto himself fabricated writings resembling these scriptures under the names of other authors, such as Fujiwara no Kamatari.[96] He also fabricated the history of the Daigengū Saijōsho.[97]

Yoshida Shinto also established the ceremony for Shinto funerals in which people are worshipped as kami. There had been little engagement with funerals prior to this as Shinto viewed death as impure, and it was only when appeasing vengeful spirits through worship such as in the case of goryō or Tenjin that people could be considered kami. Yoshida Shinto, however, held a belief in a close relationship between people and kami and thus actively conducted funerals. In fact, the Kamitatsu Shrine (神龍社) was constructed above Kanemoto’s remains and became a shrine housing him as a kami.[98]

Yoshida Shinto became an emerging force, with its rise perhaps contributed to by the societal unrest caused by the warring of the period. The sect spread widely, particularly amongst the upper class with Hino Tomiko’s patronage of the Daigengū upon its construction as well as an imperial sanction in 1473,[99] allowing it to become central to the Shinto sphere in the modern era.[100] However, it also received strong resistance, such as from the priests of both the Inner and Outer Shrines of Ise Shrine.[101]

Yoshida Shinto is the first Shinto theory to have its own doctrines, scriptures, and rituals independent of Buddhism while amalgamating Shinto from the Middle Ages and reaching across religious lines to incorporate discourse from various religions.[101] Several scholars consider the establishment of Yoshida Shinto a turning point in the religion’s history, such as Shinto scholar Shōji Okada who called it a transitional period for Shinto,[102] and historian Toshio Kuroda who claims the creation of Yoshida Shinto was the creation of Shinto itself.[103]

Having established Shinto funerals, Yoshida Shinto went on in the Sengoku period to become involved with the founding of shrines which worshipped the daimyo of the time as kami. Kanemoto himself took part in the founding of Toyokuni Shrine in which Toyotomi Hideyoshi was enshrined as a kami. Additionally, Bonshun of the Yoshida family recited Shinto prayers for Tokugawa Ieyasu and conducted Ieyasu’s Shinto funeral upon his death in accordance with his will.[104]

Early modern times

[edit]Restoration of the Shogunate's Shinto System and Imperial Rites

[edit]When the era of warfare ended and the Edo period began, the administration of shrines was reorganized. The shogunate first relieved each shrine of its current territory and granted it the privilege of "not entering into the custody of the guardian. However, what was granted was the right to make profits from the shrines, and the ownership of the land belonged to the shogunate.[105] The Shogunate also established the Jisha-bugyō as a position reporting directly to the shogun, and placed it at the head of the three magistrates, surpassing the Town Magistrate and Account Magistrate under the jurisdiction of the Rōchū.[106] In addition, a Shinto department under the jurisdiction of the temple and shrine magistrates was established to study the truths of Shinto and the rituals of rituals and to respond to the advice of the temple and shrine magistrates.[107]On the other hand, individual magistrates were assigned to specific shrines, such as Yamada bugyō, who was in charge of Ise Shrine, and Nikko bugyō, who was in charge of Nikko Tōshō-gū.[108]

In 1665 (the fifth year of the Kanbun), the shogunate issued the Priest Law for Priests of Various Shrines, which stated that ordinary Priests without rank must obtain a Shinto license issued by the Yoshida family before they can wear a hunting robe or crown, giving the Yoshida family control over almost all priests.[109] However, it was approved that those families that had been conferred ranks by the Imperial Court through transmission, such as the Jingu Shrine, Kamo Shrine, Kasuga-taisha, Usa Jingū, Izumo-taisha, and Fushimi Inari-taisha, would continue to use the same methods as before, without the Yoshida family.[110] In addition, the law stipulates penalties for neglect of duties by priests, prohibition of sales and purchases of shrine property, and the obligation to repair shrine buildings.

As for funerals, the shogunate enforced that funerals be held at dannaji temples in conjunction with the creation of the sect's personnel register, and people were obliged to hold Buddhist funerals.[111] In this case, the shrine, not the temple, proved that the Christians were not Christians, so it was called "Shinto Shinto Shinto" instead of "Temple Shinto.[111]

The Shogunate also financially supported the partial revival of the imperial rituals that had been suspended due to warfare. After 222 years of interruptions since Emperor Go-Tsuchimikado, the Dai-namesai was revived in the reign of Emperor Higashiyama, and became a regular event since Emperor Sakuramachi.[112] The Niiname-no-Matsuri was also revived in 1688 (the first year of Genroku), the year after the restoration of the Dai-namesai.[112] In 1744 (the first year of Enkyo), some of the votive offerings were also revived, including those to Kami-Shichisha and to Usa Hachiman Shrine and Kashii Shrine.[112] The Imperial Court's dispatch of imperial envoys on the occasion of the Shinnamesai festival was revived in 1647 (the fourth year of the Shohoho) by the special order of Gokomei. The ceremonial relocation of the Ise Jingu Shrine was also suspended, but was rebuilt during the Orifuji administration thanks to the efforts of Seisun and Shuyou of Keikoin. The Department of Divinities, which was destroyed by fire during the war, was replaced by the eight temples at the Yoshida Shrine, and the Divinities themselves were not rebuilt.[113]

The Shogunate also imposed restrictions on Shugendo, and in 1613 (Keichō18) issued the "Shugendo Hōdō," which stated that yamabushi must belong to either the Tōzan or Honzan sects, and forbade those who did not.[114] The latter played a leading role in folk beliefs such as Koshin-do.[114]

Popular beliefs in the early modern era

[edit]

After the early modern period, with the restoration of public safety and the improvement of transportation conditions, such as the construction of Kaido roads and the formation of Shukuba-machi, the belief in Shinto became more widespread among the general population. People formed associations called "kou" in various places, and each member of the association would accumulate a small amount of money every year, and with the joint investment, a representative chosen by lot would make a pilgrimage to a shrine and receive a bill for all the members of the association. Hongū Sengen Taisha, Kotohira-gū, Inari, and Akiba-kō, which were widely distributed throughout Japan.[115] Each group formed a relationship with a master or a predecessor, and the master arranged for the members of the group to stay overnight when praying or visiting the temple.[115]

In particular, the belief in Ise Shrine spread explosively during the Edo period. When people visited the shrine, they were welcomed at their own residences, where they performed Kagura (Shinto music and dance) and were treated to sake, Ise delicacies, and quilts. He also took them on a tour of the two palaces and places of interest, making them long to visit Ise.[116] As a result, the common people's belief in Ise has increased, and millions of common people have visited Ise Jingu all at once. It has exceeded 90%.[117]

As the general public became more active in visiting shrines, many guides were published. These included Edo meisho zue by Gekisen Saito, Namiki Gohei's Edo shinbutsu ganken juhouki, and Okayama Tori's Edo meisho e kagarenki, which catalogued and introduced temples and shrines throughout Japan.[118] In addition, Jippensha Ikku's Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige, which depicts the unusual journey of a pilgrim to Ise, and Comic books called "Hizakurige monogatari," which were written in response to this hit, and other literature on the theme of pilgrimages to shrines and temples were also published in the early modern period, contributing to the spread of Shinto faith among the general public.[119]

On the other hand, with the secularization of visits to shrines and the increase in the number of visitors, there were not a few cases where entertainment facilities such as Yūkaku, private prostitutes, theaters, and Imitation began to line up around shrines and in their precincts.[120]

In addition to the increase in the number of shrine visitors, urban commoners' festivals also became more active as a large number of spectators other than Ujiko and worshippers began to participate. In Edo, the Sanno Matsuri of Hie Shrine, the Nezu Matsuri of Nezu Shrine, and the Kanda Matsuri of Kanda Shrine, also known as the Three Great Festivals of Edo, developed, with the procession of tasteful market stalls and floats, and a costume parade of the Korean envoys and feudal lords, which attracted many spectators.[121] Outside of Edo, many urban festivals were revitalized, such as Gion Matsuri and Imamiya Matsuri in Kyoto, Tenjin Matsuri in Osaka, Hiyoshi Sanno Matsuri in Shiga, Chichibu Yatsuri in Saitama, and Takayama Matsuri in Gifu. Some of these festivals have been handed down since before the early modern period, but many of them were newly restarted after the restoration of public order in the early modern period.[121]

In the former case, the lord would assign the townspeople to do town work, such as building roads and breeding horses, and would have them participate in the festival by pulling things.[121] In the latter case, a headman was selected from each town, and the headman shared the expenses, or the expenses were shared from the expenses of the town that provided the headman.[121] Although the lords issued thrift ordinances and other regulations for festivals, they generally allowed freedom.[121]

As mentioned above, the spread of Shinto beliefs to the common people during the Edo period gave rise to a large number of lecturers who taught Shinto to the common people in an interactive manner. Zanchi Masuho, a priest of the Asahi Shinmei Shrine, was one of them. He gave oral talks on the streets with a clever joking tone, and instead of the academic Shinto that sought its basis in the Shinto scriptures, he quoted freely from the legends of Shinto, Confucianism, Buddhism, and the three religions, and attributed Shinto to matters of the heart and practice. In this way, he preached common morals such as harmony between husband and wife and equality between men and women, and he also preached the essence of Shinto, which was to work hard in accordance with one's status, in order to meet the demands of common people living in a status society.[122]

These Shinto scholars' efforts to educate the people influenced the emergence of popular Shintoists in later periods. Shoshitsu Inoue, a priest of the Shinto shrine in Umeda, started the Misogi Doctrine and gained many followers by teaching the art of "shofar," the law of eternal life, and chanting "three kinds of exorcism" to entrust the safety of one's body to the Shinto light, but the shogunate suspected him and sent him to Miyakejima.[123] Kurozumi Munetada, a priest of Imamura Shrine, also founded Kurozumikyo, which taught that everyone was one with Amaterasu without discrimination of status, and spread to a wide range of people.[123]

Ishida Baigan, the founder of Shingaku, the largest school of popular education in the early modern period, was also influenced by Shinto scholars in his youth. He emphasized the concept of "honesty", a virtue of medieval Shinto, and harmonized the teachings of Shinto, Confucianism, and Buddhism to teach ideas for the people and merchants.[124]

In the late Edo period, Ninomiya Sontoku also spread the idea of virtue, based on the principles of sincerity, hard work, decentralization, and compromise, to the people as the "great way of the dawn of creation" and the "great way of Shinto" since Amaterasu opened the reeds field and made it the Land of Mizuho. He harmonized the three religions of Shinto, Confucianism, and Buddhism with Shinto at the center, likening his learning to "a grain of Shinto, a grain of Confucianism, and a grain of Buddha.[125]

The establishment of Confucian Shinto

[edit]During the Edo period, while Buddhism took its place as the state religion under the Terashi system, ideologically it stagnated as a whole.[126]In the world of thought, it was effective as an ideology to support the Shogunate system. In the world of thought, Confucianism, especially Cheng-Zhu school, which was effective as an ideology to support the shogunate system and preached human ethics compatible with the secularism of the Edo period, flourished very much, while Buddhism was criticized by Confucians for its worldliness that was incompatible with secular ethics. Buddhism was criticized by Confucians for its worldly ethics.[127]

The mainstream theories of Shinto also shifted from Shinto and Buddhism to Confucian Shinto, which was more closely linked to Confucianism. Although there were theories of Shinto advocated by the Yangmingism school, such as Nakae Tōju's Taikyō Shinto, most of the theories of Shinto were formed by Shūji. Although Confucian thought was also incorporated in the idea of Shinto, Confucian Shinto differs in that it explicitly criticized Buddhism and attempted to escape its influence. On the other hand, the logical structure of the Confucian Shinto inherited a strong medieval esoteric tradition, and the Buddhist theory of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism was replaced by the Shuko theory, which can be said to be in a transitional period between the medieval and early modern periods.[128]

The pioneer of Confucian Shinto was Hayashi Razan. In addition to spreading his knowledge of Zhu Xi to Japan, Razan also studied Shinto, and wrote such works as "Shinto Denju" and "Honcho Jinja Ko", forming his own theory of Shinto called Rituji Shinto. The idea was that the Confucian god Li was the same as the Shinto god, and that the ultimate god was Kuni-Tokotachi.[129] While advocating Shinto and anti-Buddhism, claiming that Japan was pure and superior before the introduction of Buddhism, he also claimed that Emperor Jimmu was a descendant of Taihaku based on Chinese thought, and that the Imperial Regalia of Japan, claiming that the Three Sacred Treasures represented the three virtues of Confucianism, and tried to appeal to the high level of Japanese civilization by claiming that Japan has belonged to the Chinese sphere since ancient times.[129] In addition, the essence of Shinto is a political doctrine that has been handed down from Amaterasu to successive emperors, and rituals at ordinary shrines and festivals for common people were dismissed as "toshu-zuyaku Shinto" and mere "actors.[129]

In the case of Yoshida Shinto, Yoshikawa Tadashi, a merchant, was initiated into the Yoshida family, and was granted the "Shinto Dotosho" by Hagiwara Kanetsugu, the head of the Yoshida family, and became the official successor. He formed Yoshikawa Shinto, which removed Buddhist discourse from Yoshida Shinto and incorporated more Confucian teachings. His philosophy was that Shinto is the source of all laws and that Kunitokotachi-no-Mikoto presides over the world, and that the world and human beings are created by "truth," which is the same as God. However, because the clarity and wisdom of the Divine Light is clouded by the contamination of the human mind, it is necessary to return to the original form through tsutsumi.[130] And as a concrete way to do this, he taught that we should perform purification to purify the inside and outside, express our sincerity by performing ritual rites, and pray to the gods.[130] In addition, the Confucian view of the Five Luns is that God has given man a mission, and that the relationship between sovereign and vassal is the most important.[130]

In Ise Shinto, the late Ise Shinto, which excluded Buddhism and incorporated Confucianism, was formed in the Edo period by Nobuka Deguchi, a Shinto priest. The essence of Shinto, he wrote, is the way that Japanese people should naturally conduct themselves in their daily lives, the "way of daily use," which is to perform one's duties with honesty and purity of mind. He pointed out that it is a mistake to think that only the rituals at shrines, such as chanting congratulatory prayers and holding ball-shaped sticks, are Shinto.[131] In addition, he criticized the use of Confucianism and Buddhism for the purpose of learning, arguing that although all religions are ultimately the same, and there are many points of agreement between Shinto and Confucianism, the systems and customs of each country differ, and therefore Japanese people should respect the laws and customs of Japan.[131] However, he also stated that it is okay to study Confucianism and Buddhism as long as Shinto is placed at the center. He argued that prohibiting Buddhism and Confucianism because of their harmful effects and destroying current customs is against the natural order of things and is different from Shinto.[131]

These Confucian theories of Shinto were compiled by Yamazaki Ansai. After making a name for himself as a Confucian scholar, he was taken in by Hoshina Masayuki, Lord of the Aizu Domain, where he came into contact with Masayuki's guest teacher, Yoshikawa Tadashi, and learned Yoshikawa Shinto, leading to the creation of his own Taruka Shinto. The idea was to combine Seven Generations of the Divine Age with the Neo-Confucianism of the Shuzi school, and to believe that Kunitokotachi-no-Mikoto was the Taiji, and that the five gods that arose after him were Five Elements, and that the last two, Izanagi and Izanami, combined the Five Elements to give birth to the land, gods, and people. The spirit of the god who created the people resides in each person, and the gods and people are in a state of union called "the only way of heaven and man.[132] He said that Shinto means that people should live according to God, and that people should pray to God to obtain blessings, but that people must be "honest" in order to do so, and that "respect" is the first thing to realize this "honesty.[132] The relationship between the sovereign and the vassal is not one of rivalry or power, but one of unity, and the sovereign and the vassal have protected the country through their mutual protection.[132]、He also had a great influence on the later philosophy of the Emperor.

After the death of Yaksai Yamazaki, his pupil Shoshinmachi Kimimichi succeeded him, and the Taruka Shinto sect reached its zenith, spreading throughout the country, especially in Edo and Kyoto, widely spreading among nobles, warriors, and priests, and having the greatest influence on the Shinto world.[133] After the death of Masamichi, his disciple, Masahide Tamaki, succeeded him and organized the single, double, triple, and quadruple mysteries based on the "Mochijusho" written by Masamichi, and worked on the organization of the Taruka Shinto.[133] Some people, such as Gousai Wakabayashi, criticized this move to make the teachings secret, saying that it would obscure Yaksai's true intentions.[134]

In addition to the Tachibana family Shinto mentioned above, the Hakka Shinto and Tsuchimikado Shinto were organized under the influence of the Taruka Shinto.

Yoshimi Yukikazu, who was one of Tamaki Masahide's pupils, wrote a book entitled "Goubu-shosetsu-ben" in which he criticized Ise Shinto and Yoshida Shinto by arguing that the Shinto Goubu-shosetsu was a fake book from the Middle Ages, and also criticized Taruka Shinto, which also used the Goubu-shosetsu as its scriptures.[133] In fact, after Masahide Tamaki, Taraka Shinto began to stagnate ideologically and surrendered its mainstream position to Kokugaku.[133]

In conjunction with these anti-Buddhist ideological trends, a movement to separate Shinto and Buddhism began to spread in some of the clans that had accepted Confucian Shinto. In the Mito Domain, Tokugawa Mitsukuni investigated the history of shrines with strong Shinto-Buddhist practices in 1696 (the 9th year of the Genroku), and organized them in such a way as to wipe out the Buddhist flavor. In addition, Masayuki Hoshina of the Aizu domain carried out a similar reorganization of temples and shrines.[135] In addition, Ikeda Mitsumasa of the Okayama Domain promoted the return of priests from the Nichiren-shū Fuju-fuse and Tendai and Shingon sects, reducing the number of temples and encouraging Shinto funerals.[135] In 1647, Matsue Domain, under the leadership of Matsue Domain lord Matsudaira Naomasa, Buddhist elements were removed from the Izumo-taisha

Development of Kokugaku

[edit]In the mid-Edo period, Kokugaku began to flourish in place of Confucian Shinto. The origin of Kokugaku can be traced to poets such as Kinoshita Naganjako, Kise Miyuki, Toda Shigekazu, Shimokawabe Nagaryu, and Kitamura Kiigin, who composed poems that rejected the medieval norms of poetry in the early Edo period.[136] Qi Oki worked hard on the study of the national scriptures while moving from temple to temple, and left behind such achievements as the empirical study of poetry and Study of Kana Spelling by writing such works as "Manyo Dai Shouki" and "Waza Shouransho", and established the method of empirical study of the classics rather than reading and interpreting them in the style of Confucian and Buddhist doctrines.[137]

He was succeeded by Kada no Azumamaro. Harumitsu was born into the Higashi-Hagura family, who were priests to the Fushimi Inari Taisha shrine, and later moved to Edo to give lectures. Although there is no evidence that Harumitsu was directly apprenticed to Qi Oki, there are many books by Qi Oki in Harumitsu's collection, including "Manyo Dai Shouki", and his own commentaries on the Man'yoshu, such as "Man'yoshu Hokuanshou", mostly follow Qi Oki's readings.[138]He was greatly influenced by Qi Oki. As can be seen in the Sogakusei, Shunman had the intention of organizing history, yushoku-nijitsu, and theology as a school under the name of wagaku, and in Shunman, Shinto and language studies (by Qi oki and others) were integrated as "Kokugaku".[136]

Kamo no Mabuchi was born into a branch of the Kamo clan, who were priests at the Kamo Shrine, and studied under Kunitokazu Sugiura, a student of Harumitsu. After Harumitsu's death, Mabuchi's fame as a scholar of Japanese literature increased, and he was recommended by Kanda Zaisan to Tokugawa Munetake. Mabuchi also studied the Man'yōshū, and as part of this, he also studied the Norito, writing and annotating "Man'yōkō", "Kanjikō", and "Shūshūkō". In "Kokuyi-kou", he presented a diagrammatic methodology that extends from the study of ancient words to the study of ancient meanings and ancient ways.[139]、Anti-Confucian ideology and respect for ancient Japan was given to Kokugaku.[136] In contrast to Confucianism, which brought strife to the world by preaching humanity, the Japanese of the Kamidae period had an upright mind that converged on the "two kashikomi" of "God" and "the Emperor," and society was naturally harmonious without the need to preach humanity.[140] However, the content of the ancient path is only fragmentarily described by Mafuchi in contrast to Confucian ethics.[141]、He also taught that it was consistent with Laozhuang Thought, and did not go so far as to derive a system of thought directly from the classics to develop systematic theology.[136]