History of Leipzig

Leipzig's history has been shaped by its importance as a trading centre. Initially, its favourable location at the crossroads of trade routes[1] and the privileges granted to its trade fairs gave it its leading position in the trade of goods; later printing and book trade were added. Leipzig was never a royal residence or a bishop's seat, and was always characterised by its bourgeois character. In 1409, the city became the seat of one of the oldest universities in the German-speaking area.[2] Over the last two centuries, Leipzig has experienced strong growth and was for a time the fourth largest German city after Berlin, Hamburg and Breslau, even ahead of Munich. As an industrial location, it has declined in importance since reunification, but continues to assert itself as a trade fair city, a university city and through its cultural heritage.

Prehistory and protohistory

[edit]The first indications of the settlement of the site occupied by Leipzig date back to the neolithic period. Remains of the Linear Pottery culture and also of the Globular Amphora Culture have been discovered on the site of the St. Matthew's Cemetery. Bronze Age urns containing cremated remains have been found on the site of the Südfriedhof (South Cemetery) and the former Dominican monastery. Elbe Germanic finds from the time of the Roman Empire and the Migration Period in and around Leipzig are usually attributed to the Suebi as branch of the Hermunduri. Until 531, the area of the future city of Leipzig was part of the Thuringian Kingdom .

Middle Ages

[edit]Colonization by Slavs

[edit]After being defeated by the Franks, the Thuringians left the area between the Elbe, Saale and Mulde. Around 600, Slavs from Bohemia repopulated it, mixing with the few remaining Thuringians. The first written record of the presence of the Sorbs is due to the Burgundian Chronicle of Fredegar in 631. The area around Leipzig was called "Chutici".[3]

After several minor confrontations, the Franks invaded the territories of the Slavic tribes and founded, for example, the Diocese of Erfurt. Further expeditions against the Saxons followed and several strongholds were built (e.g. Magdeburg and Halle) to prevent incursions by the Sorbs.

At the beginning of the 10th century, several Frankish strongholds were built on the site of former Sorbian villages, for example Leipzig, where the Sorbs participated in the construction, so that it was probably already finished in 929. The dimensions were about 150 m (492.1 ft) x 90 m (295.3 ft), and the wall was about 3.50 m (11.5 ft) thick and 30 m (98.4 ft). In the center of the complex stood a defense tower. The castle (not to be confused with the later built late medieval Pleissenburg), was divided into several small castles with a main castle, all protected by bastions as outposts.[4] At this time, the first chapels were built, such as the chapel of St. Peter or that of the Irish and Scottish monks,[5] following the model of the mother abbey of St. Boniface in Erfurt.

Foundation of the city

[edit]

Leipzig was first mentioned in 1015, when Thietmar of Merseburg cites it as the place of death of Eido I, Bishop of Meissen, calling it ″Urbs Libzi″ (Chronicle VII, 25).[6] The year 1165 is generally given as the year the city was founded: the surviving document by which the Otto II, Margrave of Meissen the Rich grants town and market privileges to the locality located at the crossroads of the Via Regia and the Via Imperii. It does not bear any date, however, and was probably established later.

The location of the oldest German castle in Leipzig is controversial. Due to the geographical name, Alteburg, many researchers wondered whether it was located in Parthe meadows, near today's Lortzingstrasse. In the St. Matthew's cemetery, the Pegau Annals only attest to the existence of a castle from 1216. An outpost settlement (suburbium) surrounded by a moat was located between Große Fleischergasse and Hainstrasse. The oldest pottery found at this location dates from the end of the 9th century.[7]

The first evidence of the Leipzig mint was provided by bracteates[8] of Margrave Otto the Rich. The first documented mention of a Leipzig coin occurred around 1220.

The Easter and Michaelis[9] markets were confirmed[10] from 1190; granted in 1268, the privilege of the protective escort laid the foundations for long-distance trade. Leipzig is considered the oldest fair in the world. Since it was elevated to the rank of Imperial Fair in 1497 and received the fair right from Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor,[11] the importance of the Leipzig Fair has only grown. The fair privilege was extended by the staple right after the cities of Erfurt, Halle and Magdeburg had repeatedly violated it. In addition, a fine of 50 gold marks was to be imposed on any city that violated the predominance of the Leipzig market. Half of this sum was to go to the Empire and the rest was to be shared between the city and the duke. This did not seriously prevent the cities of Frankfurt an der Oder, Naumburg, Annaberg and Erfurt from establishing additional or new markets. That is why in 1515 a document from the Pope added the threat of ecclesiastical sanctions. Over the centuries, Leipzig continued to develop from a local or regional trading centre to an international trading place. It was particularly the East-West trade that made its reputation.

At the head of the city were originally advocati who represented the sovereign. Since the 13th century, its management was entrusted to a local magistrate (Scultetus).[12] Assessors (consuls) worked alongside him. In 1301 a mayor and a "municipal council" took over. This Council consisted of 12 to 15 members, changed every year. From the 15th century, their functions were assigned for life.

The oldest parish church, St. Nicholas, was built from 1165. In 1212 St. Thomas was added, at the same time as the St. Thomas Choir was created.[13] The 13th century saw the founding of several monasteries, including the St. Thomas cloister as a choral foundation of the Augustinians and the Cistercian monastery of St. George.[14]

The oldest hospital in the city was founded in 1213 as part of the St. Thomas Monastery, from which the current Klinikum St. Georg emerged. It served not only to accommodate the sick, but also pilgrims and the homeless. In 1439 it was purchased by the city.[15]

In 1409 the "Alma Mater Lipsiensis", the University of Leipzig, was founded,[16] which is one of the oldest German universities. At the Charles University in Prague, the voting rights of the University Nations had been changed and there were tensions between traditional theologians and Hussite theologians; for this reason German professors and students emigrated to Leipzig.

In 1485, the Partition of Leipzig gave Leipzig together with the eastern territories of the House of Wettin to the Albertine branch.[17]

The beginning of modern times

[edit]

As early as 1501, the Leipzig Council ordered the first water supply pipeline. Built using pine trunks by the master fountain builder Andreas Gentzsch, it supplied the public fountains in Brühl and the Markt, as well as the St. Paul's Monastery and many private houses with water from the Marienquelle. In 1519, the Leipzig waterworks made it possible to use water from the Pleisse.[18]

In 1519 the Leipzig Debate between Martin Luther and the opponent of the Reformation, Johann Eck, took place at Pleissenburg Castle.[19] After initial resistance, the Reformation was finally introduced in 1539 by Luther and Justus Jonas, who preached at St. Nicholas' Church. Johann Pfeffinger became the first city superintendent.

The old town hall, begun in 1556, was built in less than a year in the Saxon Renaissance style while Hieronymus Lotter was mayor.[20]

On 17 September 1631, during the Thirty Years' War, Leipzig experienced one of the greatest defeats of the Imperials led by Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, on the battlefield of Breitenfeld. Today in Leipzig, on the former manorial estate of Breitenfeld, a monument commemorates the memory of the great Swedish strategist Gustavus Adolphus. A year later, the 16 November 1632, Gustavus Adolphus was to fall during the Battle of Lützen, about 10 km (6.2 mi) southwest of the present city limits of Leipzig.[21]

From 1 July 1650 the Einkommende Zeitungen were published,[22] a successor publication to the Wöchentliche Zeitung. Appearing six times a week, it was the world's first daily newspaper.

1660 marks the beginning of the history of the city cleaning: the first municipal sweeper was hired for the Market Square. This was very necessary since one in five city dwellers were already dying from epidemics.

18th century

[edit]

Leipzig acquired the nickname "Little Paris" when this fair town, concerned with progress, equipped itself with street lighting in 1701,[23] and could from then on be compared to Paris as the ″City of Light″.[24]

At the beginning of the 18th century, Georg Philipp Telemann studied in Leipzig and founded the Collegium Musicum there. From 1723 until his death in 1750, Johann Sebastian Bach was appointed by the city council as Thomaskantor and "Director musices" (music director of all the city's churches). Among other things, the St John Passion, the St Matthew Passion, the Christmas Oratorio, the Mass in B minor and the Art of the Fugue were created.[25] In 1729, Bach took over the direction of the Collegium Musicum, which performed many of his secular cantatas and instrumental compositions in the Zimmermann Coffee House until 1741.

During the Seven Years' War, Leipzig was occupied by Prussia several times between 1756 and 1763. When King Frederick II of Prussia demanded a contribution of 1.1 million thalers from the city in November 1760, the city council refused, whereupon Frederick had the most prominent councillors and richest merchants thrown into prison. The Berlin merchant Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky intervened and achieved a reduction in the contribution to 800,000 thalers, which he advanced to the intimidated city council. He paid the sum in remelted coins with a deteriorated precious metal content (which had already triggered inflation in Prussia and Saxony in the winter of 1756/57), but had the bond issued in old, high-quality coins, thus making a profit of up to 40 percent.[26]

From 1764 to 1768 Goethe studied in Leipzig.[27] His image of Greece was based on what he saw in the Greek colony in Leipzig, which at that time was the largest Greek community outside Greece.

19th century

[edit]

While Saxony had been an ally of France since 1806, the Battle of Leipzig took place in 1813, where the armies of Austrian Empire, Prussia, the Russian Empire and Sweden, reinforced by German patriots, inflicted a decisive defeat on Napoleon and his allies, among whom was the Kingdom of Saxony. On 19 October 1813, King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony was captured in Leipzig.[28]

In 1831 the Saxon municipal regulations[29] were introduced. There was now a city council, whose members were elected by the people, and a mayor, who from 1877 bore the title of Oberbürgermeister. As early as 1874 Leipzig was separated from the district and became what is today called a Kreisfreie Stadt). However, it remained the administrative seat of the Leipzig district until Borna became district capital in the beginning 21st century.

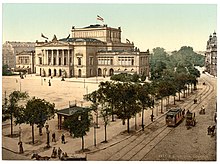

In August 1835, Felix Mendelssohn became Kapellmeister of the Gewandhaus and held this position until his death in November 1847; with his orchestra he reformed concert life in Europe. It was at this time that Symphony No. 3 (the "Scottish" Symphony), the Violin Concerto in E minor and the oratorio Elijah were born, among others.

On 7 April 1839 the railway line from Leipzig to Dresden was opened,[30] the first long-distance railway line in Germany. In the following years several railway stations in Leipzig were built in Leipzig, as predecessors of Leipzig Hauptbahnhof which was built from 1902 to 1915. Leipzig developed in its role as a railway hub in central Germany and in 1915 became the largest terminus station in Europe, surpassing Milan in terms of traffic.

During the Vormärz, on the occasion of Prince Johann's visit of August 1845, incidents occurred in Lepzig, resulting in 8 deaths; demonstrations against the Saxon government followed.[31]

On 23 May 1863, the General German Workers' Association (Allgemeine Deutsche Arbeiterverein or ADAV) was founded in Leipzig. It is considered the oldest democratic party in Germany and the first organization that foreshadowed today's Social Democratic Party of Germany.

In 1877, the first water collection site in Leipzig was built in Naunhof; in 1897, the first water tower was built in Möckern, and in 1907 in Probstheida.

20th century

[edit]

From 1899 to 1905, the old Pleissenburg Castle was demolished and replaced by the new town hall.[32] In 1913, the 91 m (298.6 ft) tall Monument to the Battle of the Nations was completed. It stands at the place where the fiercest fighting had raged and where most of the soldiers had fallen. This imposing monument is one of Leipzig's landmarks.[33]

In 1900 the German Football Association was founded in Leipzig.[34] VfB Leipzig became German football champion in 1903.

As a result of industrialisation, but also of numerous incorporations of suburban municipalities, the number of inhabitants increased very rapidly at the end of the 19th century,[35] making Leipzig before the Second World War the fifth largest city in Germany with 750,000 inhabitants.

Leipzig became the capital of books and publishing.[36] Until 1945, the Deutsche Bücherei was the most important collection of printed matters in German language.

In the First World War, around 17,000 Leipzig citizens died.[37] In the course of the German revolution of 1918–1919, a workers' and soldiers' council was established in Leipzig under the exclusive leadership of the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany, which existed until the troops of the Freikorps leader Maercker moved in in April 1919.[38]

Nazism and World War II

[edit]

During the National Socialist period the mayor was appointed by the Nazi Party. Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, however, continued to hold office until 1936; it is known that he was later involved in the 20 July 1944 plot.

In 1942, thousands of Jews from Leipzig were deported without resistance to concentration camps. Leipzig was the site of one of the heaviest bombing of the Second World War; it lasted about an hour (the alert was given at around 3:40 a.m.) and took place on 4 December 1943.[39] The attack was carried out by the Royal Air Force, under the code name Haddock. Another attack, by American aircraft, took place on 7 July 1944. The central station suffered considerable damage.[40]

The city's territory included several subcamps of the Buchenwald camp. Between 1939 and 1945, at least 60,000 women and men, girls and boys from all parts of Europe were forced to work in Leipzig. The female and male prisoners had to work under the most difficult conditions for munitions producers such as HASAG and the aircraft manufacturer Erla.[41] On 12 April 1945, in the crimes that accompanied the end of the war, 53 German and foreign prisoners were murdered in two prisons in the suburbs of Leipzig. The following day, 32 police prisoners, German, French, Austrian and Czechoslovak, died in a Wehrmacht barracks, as part of the mass murders perpetrated by the Nazis.

On 18 April 1945 units of the US 1st Army occupied the city and set up their headquarters at the Hotel Fürstenhof. There were only a few attempts at armed resistance. Finally, on 2 July 1945, following the London Protocol of 1944 on the zones of occupation and the decisions of the Yalta Conference, the Soviet army took control of the city. The Soviet military administration formed a city council whose composition, throughout the time of the GDR, was to be dictated by the communist regime.

East Germany period

[edit]

After the Second World War, Leipzig's economic importance declined sharply as it became part of the Soviet occupation zone and then the GDR, which resulted in a continuous decline in population. During the GDR, it was the capital of the Bezirk Leipzig.

In 1955/1956, the Central Stadium was built from ruins, which, with over 100,000 seats, was the largest stadium in Germany.[42]

In 1968, at the instigation of the SED leadership (chaired by Walter Ulbricht, originally from Leipzig), St. Paul's Church, the university church, was dynamited in order to complete the "socialist transformation" of Augustusplatz (then Karl-Marx-Platz).[43]

In 1969 the regional railway network (S-Bahn Leipzig) was inaugurated.[44]

As in other places in East Germany, the church in Leipzig also offered a forum to various opposition movements. The social reforms that began in the Soviet Union (Glasnost and Perestroika) in the mid-1980s led to an increasing number of political initiatives by these groups, which were primarily directed against grievances in society (lack of freedom of speech, assembly and press, electoral fraud in local elections, environmental pollution). In this context, the Monday peace prayers that had been held in Leipzig's St. Nicholas Church since September 1982 acquired political relevance when the number of visitors began to rise at the end of 1988 due to the increased social debate in the GDR. In the following period, despite the ban on opposition groups, protest actions initiated continued to increase, which repeatedly led to numerous arrests of participants by the state security authorities.[45] The wave of protests reached its peak in the autumn of 1989 during the 40th anniversary of the GDR, when Leipzig was finally the scene of mass demonstrations with several hundred thousand participants. The Leipzig rallies, which took place without violent state intervention, not least on the initiative of regional representatives of culture, the church and the Socialist Unity Party, ultimately embodied the image of peaceful protest by citizens against the prevailing socio-political conditions in their country, which was being carried out simultaneously throughout the GDR. This resulted in the opening of the inner-German border and the democratisation of the social system, as well as German reunification.[46]

After 1990

[edit]It can be stated that, although the city places great value on traditional attributes and functions such as its role as a trade fair, media and university city, Leipzig lost much of its national importance before the Second World War. As an important economic location in East Germany, Leipzig was particularly affected by the economic restructuring after German reunification. Many local industrial companies and publishers were unable to survive for long under the changed conditions. The end of the traditional spring and autumn trade fairs also changed the city's role as a trade fair location. This situation is symbolized by the creation of a new exhibition center, which opened in 1996.[47] The university was unable to save its national and international importance through two system changes.

In the 1990s, migration trends to the old federal states, suburbanization processes, and the relocation of retail from the city center to peripheral areas had a negative impact on the city's structure. Part of the population loss was offset by extensive incorporation between 1994 and 2001. Since 2001, Leipzig has seen increasing migration gains, which are also reflected in a high level of redevelopment activity in the Wilhelminian-era quarters. Part of this process is due to a certain degree of economic consolidation. On the one hand, the city strove to attract large industrial companies such as BMW,[48] Porsche[49] and Siemens, and on the other hand, with companies such as Amazon and DHL, it sought to establish itself as a logistics location.

Leipzig also tried to build on its importance as a sports city - albeit with questionable success at first. During the 2006 Football World Cup, the "old" Zentralstadion was demolished and rebuilt as a pure football stadium (home of the RB Leipzig club). The city also applied to host the 2012 Summer Olympics and won the German preliminary round in 2003 against Hamburg, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt and Stuttgart, but was not recognized as a candidate city by the International Olympic Committee .

The face of the city centre has also changed considerably in recent decades, without these processes having yet been completed. While these were initially dominated by redevelopment projects, many new buildings have been built, particularly on brownfield land and in place of buildings erected during the East Germany era. Significant construction measures include the reconstruction of the Leipzig Hauptbahnhof station, the new building of the Museum der bildenden Künste, the new building of the university on Augustusplatz and the Höfe am Brühl shopping mall in the northern city centre. In the course of the new university construction, a controversial discussion lasting several years arose as to whether and to what extent the university church, which was blown up in 1968, should be rebuilt. In 2004, it was decided that the architectural form of the new university auditorium to be built should reference the church. Following an international architectural competition, the design by the Dutch architect Erick van Egeraat was realised and completed under the name Paulinum for the university's 608th anniversary in 2017.

The City Tunnel, built between 2003 and 2013, stands out as a major infrastructure project.

On 23 September 2008, Leipzig was awarded the title “Ort der Vielfalt” (place of diversity) by the Cabinet of Germany.

In 2016, Leipzig was awarded the honorary title of “European City of the Reformation” by the Community of Protestant Churches in Europe.[50]

In 2024, Leipzig was the only East German city with a UEFA-compatible stadium to be the host city of the UEFA Euro 2024 with four matches. With RB Leipzig, Leipzig has been represented in the Bundesliga since the 2016/17 season and in some years also in the UEFA Champions League[51] and the UEFA Europa League.

See also

[edit]- Timeline of Leipzig

- List of mayors of Leipzig

- History of the Jews in Leipzig

- History of Jews in Leipzig from 1933 to 1939

- Bombing of Leipzig in World War II

- Architecture of Leipzig

Notes

[edit]- ^ Künnemann, Otto; Güldemann, Martina (2004). Geschichte der Stadt Leipzig (in German). Gudensberg-Gleichen: Wartberg Verlag. p. 8. ISBN 3-86134-909-4.

- ^ Leipzig als ein Pleißathen. Eine geisteswissenschaftliche Ortsbestimmung (in German). Leipzig: Reclam. 1995. p. 12. ISBN 3-379-01526-1.

- ^ Heydick, Lutz (1990). Leipzig. Historischer Führer zu Stadt und Land (in German). Leipzig / Jena / Berlin: Urania Verlag. p. 13. ISBN 3-332-00337-2.

- ^ Winkler, Friedemann (1998). Leipzigs Anfänge. Bekanntes, Neues, offene Fragen (in German). Beucha: Sax-Verlag. ISBN 3-930076-61-6.

- ^ Heydick (1990), p. 14

- ^ Ringel, Sebastian (2015). Leipzig! One Thousand Years of History. Leipzig: Edition Leipzig in the Seemann Henschel GmbH & Co. KG. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-361-00710-9.

- ^ Ringel (2015), p. 13

- ^ see Walter Schwinkowski: Münz- und Geldgeschichte der Mark Meißen und der Münzen der weltlichen Herren nach meißnischer Art vor der Groschenprägung – 1. Teil: Abbildungstafeln. Frankfurt (Main), 1931

- ^ Michaelis is the 29 September

- ^ Leipzig als ein Pleißathen ... p. 42

- ^ Heydick (1990), p. 22

- ^ Heydick (1990), p. 18

- ^ Leipzig als ein Pleißathen ... p.197.

- ^ Ringel (2015), p. 16

- ^ Künnemann / Güldemann, p. 24

- ^ Ringel (2015), p.18

- ^ Heydick (1990), p. 22

- ^ Künnemann /Güldemann, p. 31

- ^ Ringel (2015), p. 37

- ^ Ringel (2015), p.39

- ^ Ringel (2015), p. 43

- ^ Else Hauff: Die 'Einkommenden Zeitungen' von 1650. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Tageszeitung, in: Gazette. International journal for mass communications studies 9 (1963), Nr. 3, ISSN 0016-5492, S. 227–235

- ^ Francis Nenik (2021-12-12). "Wie das Licht nach Leipzig kam. Die ganze Geschichte, Teil 1" (in German). Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ^ Ringel (2015), p. 63

- ^ Heydick (1990), p. 43f

- ^ Ingrid Mittenzwei: Friedrich II. von Preußen, pages 108 and 123. Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1980, in German

- ^ Heydick (1990), p. 47

- ^ Künnemann / Güldemann, p.73

- ^ Repertorium zu der allgemeinen Städte-Ordnung für das Königreich Sachsen ... vom 2. Februar 1832. Leipzig 1834

- ^ Ackermann, Kurt (1990). Sohl, Klaus (ed.). Der Bau der ersten deutschen Ferneisenbahn von Leipzig nach Dresden (in German). Leipzig: VEB Fachbuchverlag. p. 19.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ringel (2015), p. 86

- ^ Ringel (2015), p. 118f

- ^ Heydick (1990), p.54f

- ^ Künnemann / Güldemann, p. 101

- ^ Heydick (1990), p. 88

- ^ Leipzig als ein Pleißathen ... pp. 129-171

- ^ Statistisches Jahrbuch der Stadt Leipzig 6. Bd. 1919–1926. Leipzig, 1928, S. 28.

- ^ Bramke, Werner; Reisinger, Silvio: Leipzig in der Revolution von 1918/1919. Leipzig 2009.

- ^ Ringel (2015), p. 169

- ^ Künnemann / Güldemann, p. 117f

- ^ "Nazi Forced Labour in Leipzig". zwangsarbeit-in-leipzig.de. Retrieved 2024-11-17.

- ^ Ringel (2015), p. 179

- ^ Ringel (2015), p. 187

- ^ Künnemann / Güldemann, p. 126

- ^ Chronik zu den Friedensgebeten und zu den politisch-alternativen Gruppen in Leipzig (Chronicle of the peace prayers and the politically alternative groups in Leipzig), in German

- ^ A brief outline of this development is given by Heinrich August Winkler in German language in: 1989/90: Die unverhoffte Einheit. In: Carola Stern, Heinrich August Winkler (Hrsg.): Wendepunkte deutscher Geschichte 1848-1990. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Tb. Verlag, 3. Aufl., 2005, ISBN 3-596-15393-X, S. 193–226

- ^ Künnemann /Güldemann, p. 136

- ^ "Sächsische Staatsregierung, Stadt Leipzig und Bundesaußenminister a.D. Joschka Fischer übernehmen ihre BMW i3 im BMW Werk Leipzig". pressebox.de (in German). 2013-11-21. Retrieved 2024-11-18.

- ^ Ringel (2015), p. 208

- ^ Die Reformationsstädte Europas.

- ^ Felix Tamsut (2017-12-09). "RB Leipzig looking forward to Champions League debut". dw.com. Retrieved 2024-11-18.