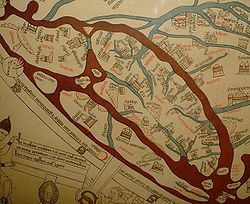

Hereford Mappa Mundi

The Hereford Mappa Mundi (Latin: mappa mundi) is the largest medieval map still known to exist, depicting the known world. It is a religious rather than literal depiction, featuring heaven, hell and the path to salvation. Dating from ca. AD 1300, the map is drawn in a form deriving from the T and O pattern. It is displayed at Hereford Cathedral in Hereford, England. The map was created as an intricate work of art rather than as a navigational tool. Sources for the information presented on the map include the Alexander tradition, medieval bestiaries and legends of monstrous races, as well as the Bible.

Although the evidence is circumstantial, recent work links the map with the promotion of the cult of Thomas de Cantilupe. Others link the map to a justification of the expulsion of Jewry from England. Potentially antisemitic images include a horned Moses and a depiction of Jews worshipping the Golden Calf in the form of a Saracen devil. The map may also reflect very patriarchal views of women as inherently sinful, including figures such as the wife of Lot being turned into a pillar of salt for gazing at the city of Sodom. Cantilupe was known for his dislike of Jews; in historian Debra Strickland's opinion he was regarded as misogynistic even by the standards of his own time.

The map would have functioned as an object to show people visiting Cantilupe's cult, and guides would have described and helped visitors to understand the content. The idea of looking, reading and hearing the stories is mentioned on the map itself. There would not have always been single, fixed ideas attached to the images, which would be interpreted symbolically, and through juxtaposition and proximity. Text in Latin and French would help guides and international visitors to understand something of its meaning.

The map suffered neglect in the post-Reformation period. By the 19th century, it was in need of repair, and it was repaired at the British Museum. However, the side panels of the original triptych were lost, and the map was detached from its wooden frame panel. The cathedral proposed to sell the map in 1988, but fundraising kept the map from sale, and it was moved to a dedicated building in 1996.

A larger mappa mundi, the Ebstorf Map, was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1943, though photographs of it survive.

Original sources

[edit]The map is based on traditional accounts and earlier maps such as the one of the Beatus of Liébana codex, and is very similar to the Ebstorf Map, the Psalter world map, and the Sawley map (erroneously for considerable time called the Henry of Mainz map). It is not a literal map, and does not conform to geographical knowledge of the time.

Among the most important sources for the map are the Historiarum adversum paganos libri septem (Seven Books against the Pagans) of Orosius, which is cited on the map. The map also draws on the Alexander myths, bestiaries and commonly accepted ideas of Monstrous Races.[1]

Interpretation and purpose

[edit]

The map has been interpreted from a topographical and encyclopedic perspective, but more recent approaches have attempted to see the map as a work of art, that conveys meanings through symbolism and associations.[2] Interpretations of the Hereford Mappa Mundi are difficult, because the original context and purpose are lost.[3] However, it is known that it formed the central panel of a triptych, a drawing of which is held by the British Library. The left panel depicted the angel Gabriel, and the right the Virgin annunciate.[4] This gives the map particular associations with the cult of the Virgin Mary, which was very prominent in Christian worship at the time, and highly developed at Hereford.[5]

There is an emerging consensus that the map played a role in promoting the cult of Thomas de Cantilupe,[6] who was later accepted as a Saint by the Holy See. This is partly based on examination of features of the cathedral and conjecture about the original placement of the triptych. There is however disagreement about the timing of its installation, whether shortly before or somewhat after 1290.[7]

The map needs therefore to be understood as an object used within that cult, as a didactic and religious object, that would have been looked at by an international audience, some of whom would be able to read the Latin or French inscriptions. It is likely that guides, whether highly educated and literate, or less so, would help ensure those looking at the map were able to interpret the figures in the correct manner. Guides could have included the cathedral canons, for example. The map itself shows some evidence that it was used this way, for instance, Hereford has nearly disappeared from it, presumably from repeated touching; and one of the map's main inscriptions states: "Let all who have this history — or who shall hear, or read, or see it — pray to Jesus in his divinity."[8]

Placement and Cantilupe cult

[edit]Dan Terkla places the map in the north transept's east wall next to de Cantilupe's shrine. Among the evidence he cites are masonry remains that can be observed at the proposed site of the triptych, including a set of eight square stone inserts, placed to block holes potentially used for wooden or stone supports (corbels) for the display. This would align with the stained glass windows above. The supports match the length of the opened triptych panels at about 3 meters wide, with a small overhang. He contends that the triptych would have fitted neatly, aligning with other features and presenting the map's key features at an appropriate height, with Jerusalem at 129 cm and the Last Judgement at 215 cm.[9] There are however potential objections to this theory; the dimensions cited by Terkla may underestimate the size of the triptych, and in any case, it would be very unusual for a decorative object to be placed so near a shrine.[10]

Another theory from Thomas de Wesselow places the triptych on another wall on the south aisle of the choir adjacent to de Cantilupe's tomb. This wall is recorded as having metal hooks which could have acted as supports for the triptych. Aligned wooden fittings on the back of the surviving central section of the triptych give credence to this view.[11]

Thomas de Cantilupe and his beliefs

[edit]If the Hereford Mappa Mundi was in fact designed for the Thomas de Cantilupe cult, then it may be expected to have reflected his interests, and align with other features of Hereford Cathedral that can be associated with his cult. The map within its triptych would have formed a central focus for pilgrims seeking divine intervention from Cantilupe. The map would be expected to reflect central concerns and beliefs or teachings of Cantilupe. Cantilupe was "an inveterate enemy of the Jews",[12] and his demands that they be expelled from England were cited in the evidence presented for his canonization.[13] Other evidence for his holiness included refraining from the company of women, regarding them as a source of temptation.

Cantilupe's views depicted on the map may include his aversion to Jews and his misogyny. In Debra Strickland's view, the map reflects a post-Expulsion narrative, conflating the Exodus of the Bible with the contemporary expulsion, and as outlined below, setting out why Christians should believe that Jews are deserving of such punishment.[14]

Authorship and patronage

[edit]The production of the map is likely to have involved the patronage of up to four men, Thomas de Cantilupe, Richard of Haldingham, Richard de Bello and Richard Swinefield, the Bishop of Worcester after Cantilupe. Richard of Haldingham, who died in 1278, may have been a senior relative of de Bello, and appears to be credited on the map as the designer (who "made and laid it out"). Richard de Bello's career from the later 1280 and 90s is linked to Swinefield's patronage in Lincoln, where Swinefield was briefly treasurer. Finally, of course, in creating the map for the Cantilupe cult, it was a sign of Swinefield's gratitude to his benefactor.[15] However, these possible links remain speculative, and it is equally possible that Richard of Haldingham and Swinefield knew each other directly, even assuming that the Haldingham that died in 1278 was the original drafter identified on the map.[16]

There is possible evidence of female patronage contributing to the map's production, in the single well-dressed, arisocratic female figure among the elect drawn on the top left handside of the map, and in the drawing of the modestly dressed and therefore piously presented handmaiden offering the Virgin Mary a crown.[17]

It was long believed that the mappa mundi was created, not in Hereford, but in Lincoln because the city of Lincoln was drawn in considerable detail and was represented by a cathedral (accurately) located on a hill near a river.[18] Hereford, on the other hand, was represented only by a cathedral, a seeming afterthought drawn by a different hand when compared with other features of the map.[19] However, more recent research on the origin of the wood in the frame suggests it may in fact have been created in or around Hereford.[20]

Presentation of Jews and the Exodus itinerary

[edit]Strickland has attempted to interpret the map's images of medieval Jewry and associated bible stories to understand what it may have been trying to convey about Jews and Judaism. She notes that this was a particular concern in England, where the Jews were expelled in 1290, and also of Hereford cathedral and its leadership, who had been in conflict with the local Jewish population.[14] The map has several depictions of Jews (Judaei), mostly relating to depictions of the Exodus.[14] These are unusual, not least as they would normally be identified as historical "Israelites" or similar formulations rather than by the contemporary term "Jews".[21] The Exodus cycle is particularly prominent, indicating unusual significance, as it is not found on other similar medieval religious maps.[22]

Some of the images are clearly derogatory and anti-semitic. For instance, within the Exodus cycle, a prominent scene depicts the worship of the Golden Calf. However, the Golden Calf is depicted as a devil defacating coins onto its altar.[23] The devil is labelled "Mahu(n)", a name for imaginary idols believed to be worshipped by Muslims, building an association with figures elsewhere on the map negatively representing Saracens.[24] The scene also depicts Christian crosses as present on the altar. This arguably moves the image into a depiction of host desecration, but at a minimum places the Jews in a position of mocking Christians. The four men labelled "Judaei" worshipping the devil hold a blank scroll, a symbol used to denote the association of Jews with scrolls containing the Word of God, yet in the view of Christians, having an inability to understand and accept it.[25] Overall, the Golden Calf scene, by labelling Israelites as "Jews", associating them with the mockery of Christians and with conceptions of Muslims or Saracens of the period through the "Mahun" figure, connects the Exodus story with contemporary Jews.[25]

The "blank scroll" of the Golden Calf scene also connects with the nearby depiction of Moses receiving the Ten Commandments, directly above. This can be read as the Jews receiving the law from God, and then rejecting it, transforming the Exodus story from that of redemption to rejection and damnation.[26]

The Moses figure can also be interpreted negatively. He is depicted with yellow horns, near red coloured seas and as already noted, is close to another devil.[a] The red and yellow colour combination is well known from other derogatory depictions of Jews, and can be read as reinforcing negative stereotypes of Jews.[28] A coffin with a Christian cross placed next to Moses may represent Joseph's bones being taken back to Israel, but could also represent the contemporary death of the Old Law, God's rejection of the Jews, and the replacement of the Mosaic law by the Christian message. It may recall Jesus' comparison in Matthew 23.27 of the scribes and Pharisees to whitened tombs.[29] Lastly, Moses is placed in proximity to dragons patrolling the entrance to hell, through a diagonal alignment.[29]

The Biblical Exodus can be read as a parallel for the near contemporary 1290 expulsion of the Jews from England. The itinerary has beasts and objects placed near it which may reinforce negative portrayals of Jews. At the start of the Exodus, at Ramasses, a yale and a mandrake stand beside the start of the route. The yale's horns echo those of Moses. The next beast encountered on the path is near the Jews worshipping the Golden Calf is a phoenix. The phoenix symbolised Christ's resurrection, as it emerges intact from fire after three days; in the bestiaries, this was said to echo the prophecy of Jesus that he had the power to lay his life down and take it up again, which had angered the Jews. After three loops representing forty years of travel each, the path encounters the disobedient wife of Lot, on the point of being turned into a pillar of salt for looking back onto the city of Sodom. Here also stands a marsok, with different kinds of feet, which may be linked to the shape changing hyena, itself associated in bestiaries with Jews as an unclean, sex-changing animal. Positioned between the Tower of Babel and Lot's wife, the marsok may also function to connect the Exodus story to the sin of pride. The destination of the Exodus path is Jericho, positioned just above the crucified Christ, whose hand points back to the Jews worshipping the Golden Calf, linking the crucifixion to those deemed responsible in medieval theology.[30]

Jews depicted in the Gog and Magog myth

[edit]There are a total of four references to Gog and Magog.[31] At the top left of the map, near the Day of Judgement, is a description of the cannibalism of fili caim maledicti, or "accursed sons of Cain". These Jewish figures are a frequent depiction on medieval maps, and derived from the Alexander cycle myth. They are in the myth fated to fight Christendom at the end of time.[24]

Presentation of women

[edit]Strickland notes that the map conveys a "pervasive masculinity: male ecclesiastical headgear, flat chests, beards, tonsures, testicles, and penises abound",[32] and the "entire visual field is enframed, patrolled, and occupied by males".[33] She contrasts this with the female figures, which she believes depict aspects of the prevailing misogynistic depiction of women as fundamentally proud, disobedient and lustful.[34] The Virgin Mary stands in medieval thinking as the role model for women, as virginal and free from sin, and therefore complements rather than subverts this depiction.[5]

Some twenty figures that represent women, of which the most important represents the Virgin Mary, positioned at the top of the map at the Last Judgement, where she bares her breasts in an act of supplication. Other figures include a handmaiden presenting Mary with a crown, and a siren near Jerusalem bearing a mirror. The wife of Lot gazes towards Sodom and Gomorrah, and Noah's wife stands beside him. There are also a prominent female Epiphagus, a Psyllian, and a further twenty other non-human females.[35]

The four most prominent women are positioned around the Tower of Babel, a symbol of the sin of pride, viewed in the Christian morality of the time as the root of all evil, and also the sin most closely associated with women.[35] The Tower of Babel symbolised pride as God cast it down for attempting to reach heaven. In general, women were associated with the related sins of vanity, gluttony, and avarice. Religious teachings recognised the necessity of marriage and reproductive sex, but emphasised virginity as the preferable state. The four women who stand around the tower were those depicted in contemporary Christian morality as having specific failings related to pride. The women and female figures together depict pride, disobedience and sexual misconduct, fulfilling the map's didactic role, in reinforcing "misogynisitic ideologies" and the social control of women.[36]

Contents

[edit]Drawn on a single sheet of vellum, it measures 158 cm by 133 cm,[37] some 52 in (130 cm) in diameter and is the largest medieval map known still to exist. The writing is in black ink, with additional red and gold, and blue or green for water (with the Red Sea (8) coloured red). It depicts 420 towns, 15 Biblical events, 33 animals and plants, 32 people, and five scenes from classical mythology.[37]

Utilizing the contemporary medieval styled T-O map of the time, the map is a biblically inspired map which shows Jerusalem drawn in the centre of the circle; east is on top, showing the Garden of Eden in a circle at the edge of the world (1).[38] Great Britain is drawn at the northwestern border (bottom left, 22 and 23). Curiously, the labels for Africa and Europe are reversed, with Europe scribed in red and gold as "Africa" and vice versa.[37] The Mediterranean Sea is shown at the bottom center, with the Straits of Gibraltar marking its most western point.[38]

As noted, it does not correspond to the geographical knowledge of the 14th century. For example, the Caspian Sea (5) connects to the encircling ocean (upper left). This is in spite of William of Rubruck's having reported it to be landlocked in 1255, several decades before the map's creation; see also Portolan chart.

Various animals not well known to Europeans at the time, such as elephants and camels, are depicted. Elephants were shown to be very practical beasts of war, as they were strong enough to transport siege equipment across great distances, as well as being capable of supporting platforms from which rows of archers were able to stand and fire, or so envisioned the medieval English cartographers. Mythical beasts such as the legendary monoceros are depicted on the map. A number of monsters and inhuman races are present. One such race is the Blemmyes, a headless tribe whose facial features were situated on their chests.[39]

The "T and O" shape does not imply that its creators believed in a flat Earth. The spherical shape of the Earth was already known to the ancient Greeks and Romans and the idea was never entirely forgotten even in the Middle Ages, and thus the circular representation may well be considered a conventional attempt at a projection: in spite of the acceptance of a spherical Earth, only the known parts of the Northern Hemisphere were believed to be inhabitable by human beings (see antipodes), so that the circular representation remained adequate.[40] The long river on the far right is the River Nile (12), and the T shape is established by the Mediterranean Sea (19-21-25) and the rivers Don (13) and Nile (16).

It is the earliest known map to depict the mythical St Brendan's Isle,[41] which then appeared on many other maps. including Martin Behaim's Erdapfel of 1492.

Locations

[edit]

0 – At the centre of the map: Jerusalem, above it: the crucifix.

1 – Paradise, surrounded by a wall and a ring of fire. During World War II this was printed in Japanese textbooks since Paradise appears to be roughly in the location of Japan.[42]

2 – The Ganges and its delta.

3 – The fabulous island of Taphana, sometimes interpreted as Sri Lanka or Sumatra.

4 – Rivers Indus and Tigris.

5 – The Caspian Sea, and the land of Gog and Magog

6 – Babylon and the Euphrates.

7 – The Persian Gulf.

8 – The Red Sea (painted in red).

9 – Noah's Ark.

10 – The Dead Sea, Sodom and Gomorrah, with the River Jordan, coming from the Sea of Galilee; above: Lot's wife.

11 – Egypt with the River Nile.

12 – The River Nile (?), or possibly an allusion to the equatorial ocean; far outside: a land of the monstrous races, possibly the Antipodes.

13 – The Azov Sea with rivers Don and Dnieper; above: the Golden Fleece.

14 – Constantinople; left of it the Danube's delta.

15 – The Aegean Sea.

16 – Oversized delta of the Nile with Alexandria's Pharos lighthouse.

17 – The legendary Norwegian Gansmir, with his skis and ski pole.

18 – Greece with Mount Olympus, Athens and Corinth

19 – Misplaced Crete with the Minotaur's circular labyrinth.

20 – The Adriatic Sea; Italy with Rome, honoured by a popular Latin hexameter; Roma caput mundi tenet orbis frena rotundi ("Rome, the head of the world, holds the reins of the round globe").

21 – Sicily and Carthage, opposing Rome, right of it.

22 – Scotland.

23 – England.

24 – Ireland.

25 – The Balearic Islands.

26 – The Strait of Gibraltar (the Pillars of Hercules).

Post-Reformation history

[edit]The Hereford Mappa Mundi hung, with little regard, for many years on a wall of a choir aisle in the cathedral. During the troubled times of the Commonwealth the map had been laid beneath the floor of Bishop Audley's Chantry, where it remained secreted for some time. In 1855 it was cleaned and repaired at the British Museum. During the Second World War, for safety reasons, the mappa mundi and other valuable manuscripts from Hereford Cathedral Library were kept elsewhere and returned to the collection in 1946.[43]

Threatened sale and new public display

[edit]

In 1988, a financial crisis in the Diocese of Hereford caused the Dean and Chapter to propose selling the mappa mundi.[44] After much controversy, large donations from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, Paul Getty and members of the public kept the map in Hereford and allowed the construction of a new library designed by Sir William Whitfield to house the map and the chained libraries of the Cathedral and of All Saints' Church. The new Library Building in the south east corner of the cathedral close opened in 1996.[43][37] An open-access high-resolution digital image of the map with more than 1,000 place and name annotations is included among the thirteen medieval maps of the world edited in the Virtual Mappa project. In 1991 British Rail Class 31 locomotive No.31405 was named "Mappa Mundi" at a ceremony at the Hereford Rail Day.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The "horned" aspect could be due to a mistranslation of Moses as cornuta (horned) in the Vulgate Bible, but this itself may not have been a neutral mistake. There is also evidence of association of Jews with devils in medieval sermons, and in any case, Strickland argues, the audience would be likely to associate horns with devilry. Stephen Bertman makes similar points regarding medieval depictions of a horned Moses.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ Strickland 2018, p. 423

- ^ Black 2010.

- ^ Harvey 2010, p. 33

- ^ Kupfer 2019, pp. 228–9

- ^ a b Strickland 2022b, p. 9.

- ^ Terkla 2004, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Strickland 2018, pp. 424, 463, Terkla 2004, pp. 131–151

- ^ Strickland 2022b, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Terkla 2004, pp. 141–145

- ^ Wesselow 2013, pp. check.

- ^ Harvey 2010, pp. 32–33, Wesselow 2013, pp. 189–198

- ^ Tout 1886; quoted by Hillaby 1990, p. 466

- ^ Strickland 2018, p. 463

- ^ a b c Strickland 2018

- ^ Terkla 2004, p. 139-40.

- ^ Harvey 2000, p. 560.

- ^ Strickland 2022b, pp. 32–4.

- ^ Johnson 2023

- ^ Harvey 2010, p. ?.

- ^ BBC 2015.

- ^ Strickland 2018, p. 429

- ^ Wesselow 2013, p. 196.

- ^ Strickland 2003, p. 166.

- ^ a b Strickland 2018, p. 431

- ^ a b Strickland 2018, pp. 430–31

- ^ Strickland 2018, pp. 432–34

- ^ Bertman 2009, pp. 100, 102, 105.

- ^ Strickland 2018, p. 436.

- ^ a b Strickland 2018, p. 437

- ^ Strickland 2018, p. 437-44.

- ^ Mittman 2018, pp. 20–23.

- ^ Strickland 2022b, p. 3

- ^ Strickland 2022b, p. 4

- ^ Strickland 2022b, p. 6.

- ^ a b Strickland 2022b, p. 5

- ^ Strickland 2022b, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d Edson 1997

- ^ a b Brown 2017, p. 20

- ^ Wellesley 2022.

- ^ Woodward 1985

- ^ Magasich-Airola & de Beer 2007

- ^ Ayabe 2007, p. 186.

- ^ a b Alington 1997

- ^ Driver 1988

Sources

[edit]Secondary sources

[edit]- Alington, Gabriel (1997). The Hereford Mappa Mundi. Gracewing. ISBN 9780852443552.

- Ayabe, Munehiko (2007). 「知られざる古代日本キリスト伝説」. 学研. ISBN 978-4054035812.. (綾部 宗彦)

- Bertman, Stephen (2009). "The Antisemitic Origin of Michelangelo's Horned Moses". Shofar. 27 (4). Purdue University Press: 95–106. doi:10.1353/sho.0.0393. JSTOR 42944790.

- Brown, Kevin J. (2017). Maps Through the Ages. White Star Publishers. p. 20. ISBN 9788854416154.

- Edson, Evelyn (1997). Mapping Time and Space: How Medieval Mapmakers Viewed Their World. The British Library.

- Harvey, P. D. A. (2000). "Mappa Mundi". In Aylmer, Gerald; Tiller, John (eds.). Hereford Cathedral: a History. London: Hambledon Press. pp. 557–562. ISBN 1852851945.

- Harvey, P. D. A. (2010). Mappa Mundi: The Hereford World Map (2nd ed.). Hereford: Hereford Cathedral.}

- Hillaby, Joe (1990). "The Hereford Jewry, 1179-1290 (third and final part) Aaron le Blund and the Last Decades of the Hereford Jewry, 1253-90". Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club. XLVI (III): 432–487.

- Kline, Naomi Reed (2006). "Alexander Interpreted on the Hereford Mappamundi". In Harvey, P.D.A. (ed.). The Hereford World Map: Medieval World Maps and their Context. British Library.

- Kline, Naomi Reed (2003) [2001]. Maps of Medieval Thought: The Hereford Paradigm (paperback ed.). Boydell. ISBN 0851159370. OL 22373026M.

- Kupfer, Marcia (2016). Art and Optics in the Hereford Map: An English Mappa Mundi, c. 1300. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300220339.

- Kupfer, Marcia (2019). "The Hereford Map (c. 1300)". In Terkla, Dan; Mellea, Nick (eds.). A Companion to English Mappaemundi of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer. pp. 226–52. ISBN 978-1-78327-422-2.

- Magasich-Airola, Jorge; de Beer, Jean-Marc (2007). America Magica: When Renaissance Europe Thought It Had Conquered Paradise (2nd ed.). Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1843312925.

- Mittman, A. S. (2018). "England is the World and the World is England". Postmedieval. 9 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1057/s41280-017-0067-x.

- Rudolph, Conrad (2018). "The Tour Guide in the Middle Ages: Guide Culture and the Mediation of Public Art". Art Bulletin. 100 (1): 36–67. doi:10.1080/00043079.2017.1367910. JSTOR 44973273.

- Strickland, Debra Higgs (2003). Saracens, demons, and Jews: making monsters in Medieval art. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691057192.

- Strickland, Debra Higgs (2018). "Edward I, Exodus, and England on the Hereford World Map" (PDF). Speculum. 93 (2): 420–69. doi:10.1086/696540.

- Strickland, Debra Higgs (2022a). "Otherness on the Hereford World Map (c. 1300)". IKON: Journal of Iconographic Studies. 19: 19–28. doi:10.1484/J.IKON.5.132348. ISSN 1846-8551.

- Strickland, Debra Higgs (2022b). "The female presence on the Hereford World Map" (PDF). Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art. 1 (8): 1–57. doi:10.61302/LZBT9907. ISSN 1935-5009.

- Terkla, Dan (2004). "The Original Placement of the Hereford Map". Imago Mundi: The International Journal for the History of Cartography. 56 (2). Routledge: 131–151. doi:10.1080/0308569042000238064.

- Tout, Thomas (1886). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 08. pp. 448–452.

- Wesselow, Thomas de (2013). "Locating the Hereford Mappamundi". Imago Mundi. 65 (2): 180–206. doi:10.1080/03085694.2013.784555.

- Woodward, David (December 1985). "Reality, Symbolism, Time, and Space in Medieval World Maps". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 75 (4): 517–519. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1985.tb00090.x. JSTOR 2563109.

News and web articles

[edit]- BBC (28 May 2015). "Cathedral lays claim to medieval map". BBC News. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Black, Annetta (2010). "Hereford Mappa Mundi". Atlas Obscura.

- Connelly, Erin (19 November 2019). "Discover the Last Chained Libraries in England". Europe Up Close.

- Driver, Christopher (19 November 1988). "World time forgot: the 13th-century world map up for sale is not the only neglected treasure of Hereford Cathedral". The Guardian.

- Johnson, Ben (2023). "The Hereford Mappa Mundi". Historic UK.

- Wellesley, Mary (21 April 2022). "In Hereford". London Review of Books. 44 (8).

Further reading

[edit]- Bevan, W. L.; Phillott, H. W. (1873). Medieval Geography: An Essay in Illustration of the Hereford Mappa Mundi. London: Stanford. An extensive early study.

- Westrem, Scott D. (2001). The Hereford Map. Terrarum Orbis 1. Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 2-503-51056-6. A series of close-up photographs of the entire map, along with annotated transcriptions and English translations of all the text thereon.

External links

[edit]- "Explore the Hereford Mappa Mundi" at the official dedicated website launched in 2014

- "The Mappa Mundi" at the Hereford Cathedral site

- "The Hereford Mappamundi" by J. Siebold Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Discussion by Janina Ramirez and Peter Frankopan: Art Detective Podcast, 22 Mar 2017

- Digital Facsimile edition: Virtual Mappa: Digital Editions of Early Medieval Maps of the World, eds. Martin Foys, Heather Wacha, et al. (Philadelphia, PA: Schoenberg Institute of Manuscript Studies, 2020). DOI: 10.21231/ef21-ev82.

- The Mapping Mandeville Digital Project, ed. John Wyatt Greenlee, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville plotted onto the Hereford Mappa Mundi