Habroscelimorpha dorsalis dorsalis

| Northeastern beach tiger beetle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Family: | Cicindelidae |

| Genus: | Habroscelimorpha |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | H. d. dorsalis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Habroscelimorpha dorsalis dorsalis (Say, 1817)

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

|

Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis Say, 1817 | |

Habroscelimorpha dorsalis dorsalis (synonym Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis), commonly known as the northeastern beach tiger beetle, is the largest subspecies of eastern beach tiger beetle (Habroscelimorpha dorsalis).[2] In 2012, Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis was reclassified under the name Habroscelimorpha dorsalis dorsalis, but the names are used synonymously in recently published literature.[5] Fitting to its common name, the northeastern beach tiger beetle dwells along the U.S. northeast coast in small sand burrows. The beetle is diurnal and can be spotted by its light tan coloring with dark lines and green hues on its thorax and head.[3]

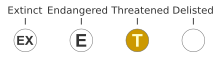

The northeastern beach tiger beetle is not only an important part of the delicate coastal food web, but can serve as an indicator of beach integrity and quality. The beetle is highly susceptible to abundant human activity and beach erosion. In 1990, the northeastern beach tiger beetle was listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) due to massive population declines throughout its range.[2]

Taxonomy

[edit]There are four subspecies of Cicindela dorsalis: Cicindela dorsalis media, Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis, Cicindela dorsalis saulcyi, Cicindela dorsalis venusta. Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis is the only subspecies to be listed under the ESA.[6] The northeastern beach tiger beetle only overlaps in range with Cicindela dorsalis media, which occupies the southeast coast of the U.S. ranging from Maryland to Florida.[7]

Physical description

[edit]The northeastern beach tiger beetle is one of the physically larger subspecies of Cicindela dorsalis with a body length if roughly 12–17 millimetres (0.47–0.67 in). Its hardened forewings, also called elytra, acquire varying shades of white and tan. The northeastern beach tiger beetle has wings hidden under these elytra. The beetle has large white and black jaws, long antennae, and long legs that allow them to move quickly across hot sand.[8]

The body of this species, including the thorax and bronze-colored head, displays chestnut-colored lines, and sometimes patches of green coloring. Elytra of older beetles tend to be a lighter, whiteish color due to friction with sand particles. Even in the larval stages, the northeastern beach tiger beetle possesses large jaws in order to efficiently catch prey. Larvae also have small hooks that extend from their abdomen in order to grasp the side of their burrows. This prevents the larvae from being lifted out of their burrows when they catch prey. However, the larvae lack a hard cuticle, which makes it difficult to survive outside their burrows in hot summer months.[8][9]

Ecology and behavior

[edit]Diet

[edit]The northeastern beach tiger beetle remains an invertivore throughout its lifecycle—meaning the beetle only preys on invertebrates such as small amphipods, flies, or other beach arthropods. Adult beetles actively hunt their prey as well as scavenge on dead prey, such as washed up fish and crabs on the shoreline.[9] The immature larvae wait in their burrows for passing prey, primarily small arthropods. The northeastern beach tiger beetle uses its long, sharp mandibles in order to catch their food and crush it with lightning speed, hence its common name: “tiger” beetle.[8]

Predation

[edit]Predators of the northeastern beach tiger beetle include wolf spiders, asilid flies, and birds. These account for about 6% of adult beetle mortality.[5] A decline in northeastern beach tiger beetle populations disturbs the balanced beach ecosystem as beetle predators encounter food scarcity, and populations of small amphipods and flies increase with fewer predators like the northeastern beach tiger beetle.[9]

Reproduction

[edit]The northeastern beach tiger beetle begins its mating season as early as June, and the season lasts until late July. The female beetle lays eggs in shallow nesting pits, which are usually about 2.5 centimetres (0.98 in) below the surface of the beach. In order for a site to be considered a “breeding site,” the beach must have a width of at least 6.5 feet (2.0 m) (16–26 feet or 4.9–7.9 metres wide is preferred), length of at least 325 feet (99 m), and a population of at least 30 adults. On beaches with these conditions, it can be assumed there are larvae present. Depending on the sand’s moisture, the larvae will hatch from their eggs after approximately 12 days. The larvae then dig a burrow to develop in and undergo three life “stages” (more information under Life History).[5][9]

Life history

[edit]The northeastern beach tiger beetle relies on warm, sunny days to thermoregulate its body temperature—their bodies must be kept at high temperatures to maximize their predatory ability. Given this requirement, the adult beetles emerge around mid-June and peak in abundance in July. Within two weeks after emergence from their larval state, the beetles remain in close proximity to their burrows. After peak abundance in July, dispersal becomes more common, and adults move about 5–12 miles (8.0–19.3 km) from their original burrow spot.[9]

Adult beetles are most active during the day, but display nocturnal activity on warmer nights. When active during the day, adult beetles can be found close to the water’s edge feeding, mating, and absorbing the sun. At night, it is common for females to sit at the bottom of their vertical sand burrow, while the males are positioned to guard the top of the hole. As the temperatures drop in the fall, the adult beetles die off. Larvae, however, are able to seal up their burrows and hibernate for the winter months.[8]

Larvae can be classified into three developmental stages, also called “instars”. Between each stage, the larvae grow bigger and expend more energy. The first-instar larvae emerge from their eggs in late July and early August. They reach the second instar by September, and reach the third instar by mid-March. At this time, some of the larvae develop into adult beetles by June in the same year that they reach their third larval instar. However, it is common for larvae to remain in this third instar for an additional year and emerge as adults the following June. Larvae closest to the water’s edge develop faster given the higher abundance of prey and increased water exposure. Throughout their development, larvae almost exclusively remain in the same burrow. However, larvae have been known to move burrow sites when disturbed or if prey is scarce. Larval activity varies with temperature, moisture, and tide levels—larvae are extremely susceptible to hot, dry conditions and will remain inactive during the summer. Larvae are most active during the fall and spring.[8]

Habitat

[edit]Habitat description

[edit]As evident by their name, the northeastern beach tiger beetle lives exclusively along the northeastern U.S. shorelines. These beetles prefer beaches with much diverse vegetation growing in the dune area and need medium-coarse sand to dig suitable burrows.[10] The top of the burrows appear as perfectly circular holes. As the beetle larvae develop, their burrow depths increase. A burrow for a first instar is roughly 10.0 centimetres (3.9 in), that of a second instar is 15.0–17.5 centimetres (5.9–6.9 in), and that of a third instar is 22.5–35.0 centimetres (8.9–13.8 in). Adult burrows are about 5–8 centimetres (2.0–3.1 in) deep.[8] The further a larval burrow is from the water’s edge, the deeper the larvae must dig for moist conditions.[11] In areas that experience frequent and harsh storms, larvae move further up the beach and into the high tide drift zone. Larvae can survive in a flooded burrow for only three to six days.

Habitat destruction is a significant threat to the northeastern beach tiger beetle. As more shorelines along the east coast of the U.S. experience erosion events due to hurricanes, harsh storms, and anthropogenic factors, habitable shoreline is becoming increasingly sparse for beetles.[5] Several studies have shown that beach width is a “critical indicator of suitable habitat”—the northeastern beach tiger beetle prefers beaches that are at least 6 metres (20 ft) wide.[12] Third instar larvae have been found on much narrower beaches, some less than 2 m wide, since these larvae rarely move from their burrows and beaches erode as the larvae develop.[5]

Historical and present range

[edit]Northeastern beach tiger beetle populations boomed along the northeast beaches “in great swarms” in the late 19th century and early 20th centuries.[13] This beetle inhabited Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia.[2][5] Starting in the 1920s, scientists began to notice that northeastern beach tiger beetle populations were declining.[3] Currently, the northeastern beach tiger beetle appears to be extirpated (locally extinct) from Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey.[5]

Critical habitat areas are beaches which have been deemed vital to conserving the northeastern beach tiger beetle species. When the species was listed as “threatened” in 1990, no critical habitat was proposed, and there continues to be no official critical habitat claimed today.[3] However, protected areas have been identified in Virginia and Maryland. Virginia areas include Sandy Point Island, Rigby Island, Bethel Beach, Winter Harbor, Picketts Harbor, and Kiptopeke State Park. Flag Ponds, Maryland is also an area under state protection. In 2015, the Center for Biological Diversity submitted a petition to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to designate approximately 42,955 acres of northeastern coast as critical habitat.[14] This included areas within the Chesapeake Bay, New Jersey, Long Island, southeastern Massachusetts, Cape Cod, and Martha’s Vineyard. This petition has not come to fruition.

In an effort to restore the northeastern beach tiger beetle to its historical range, the recovery plan outlined by the USFWS in 1994 defined 9 different Geographical Recovery Areas (GRAs) where the beetle and/or the ecosystem need to be conserved. GRAs 1-9 are the following: Coastal Massachusetts and the Islands, Rhode Island and Block Island and Long Island Sound, Long Island, Sandy Hook to Little Egg Inlet in New Jersey, Calvert County in Maryland, Tangier Sound in Maryland, Eastern Shore of Chesapeake Bay in Virginia, Western Shore of Chesapeake Bay in Virginia (north of the Rappahannock River), and Western Shore of Chesapeake Bay in Virginia (south of the Rappahannock River). These GRAs are not officially deemed “critical habitat,” and describe just the general geographical areas in which the northeastern beach tiger beetle populations should be restored. In the 5-Year Review conducted by the USFWS in 2019, only 5 of these GRAs currently have populations. Within the majority of these GRAs, the populations continue to decline.[8][5]

Status and conservation

[edit]Historical and present population size

[edit]In Massachusetts, the northeastern beach tiger beetle remains extirpated in most sites. On Martha’s Vineyard, surveys conclude a total of 3,388 adult beetles were present in 2005; this number dropped to about 374 adults in 2018. Fortunately, there has been success at the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge in Chatham, MA where adult beetles were translocated from Martha’s Vineyard from 2000 to 2003. After this translocation, 26 adults were observed in 2004 and this grew to 2,687 adults living at the Monomoy site by 2018.[5][9]

In Sandy Hook, New Jersey, there have been several translocation efforts since 1994. However, none of these efforts have been successful and researchers have not observed any adult northeastern beach tiger beetles in the area since 2008.[5]

In Calvert Beach, Maryland, the number of adult beetles declined from 4,198 adults in 1991 to 2,307 adults in 2018. However, adult beetle numbers are recovering from a record low of 72 adults in 2009. Additionally, both Cedar Island and Janes Island in Maryland have experienced growing populations. On Cedar Island, the adult beetle population jumped from 1,095 adults in 2004 to 3,202 adults in 2016. On Janes Island, the adult beetle population jumped from 369 adults in 2004 to 4,286 adults in 2017.[5][9]

On Virginia’s eastern shoreline of the Chesapeake Bay the overall numbers of adult beetles and the number of populated sites have decreased. In 1999, a survey reported 32,143 adults. This decreased to the 25,488 adult beetles counted in 2016. Northeastern beach tiger beetles also struggle on Virginia's western shoreline of the Chesapeake Bay declining from 26,685 adult beetles in 1998 to 7,832 adults in 2017. Unfortunately, Hurricane Isabel in 2003 and Hurricane Ernesto in 2006 significantly contributed to the decline in this region.[5][9]

History of ESA listing

[edit]USFWS first publicly recognised the decline in the northeastern beach tiger beetle population with the Federal Register “Notice of Review” published on May 22, 1984.[15] This notice covered invertebrates to be considered for classification as “threatened” or “endangered” under the ESA. The northeastern beach tiger beetle, along with the related Puritan tiger beetle, were placed in category 2.[3] This designation indicated there was insignificant data available, but the species could possibly qualify for listing in the future. Shortly thereafter, the USFWS enlisted Dr. Barry Knisley of Randolph-Macon College to survey the populations and publish a report. Knisley’s work revealed a “precipitous” decline from 1920-1950, and the population had been steadily decreasing since.[16] After Knisley’s report, the Federal Register “Notice of Review” published on January 6, 1989 included the Northeastern beach tiger beetle in category 1, which deemed the species eligible to be listed under the ESA.[15]

On October 2, 1989, the USFWS proposed in the Federal Register to list Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis as “endangered.” This proposed rule was released to the public for commentary before the final ruling on how the beetle would be listed under the ESA. Developers owning a substantial amount of land on Virginia’s eastern shore and the Virginia Natural Heritage Program submitted comments in favor of listing the species as “threatened” because new populations had been discovered in Virginia. On August 7, 1990 Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis was listed as a “threatened” species under the ESA due to the beetle’s reduced geographical range and high susceptibility to anthropogenic and natural threats.[3]

The first 5-Year Review, in which the USFWS evaluates the recovery progress of the species, was published on March 19, 2009—long after the species was listed under the ESA. This review found that recovery efforts for the Northeastern beach tiger beetle did not meet the established criteria in the initial recovery plan. The review proposed improvements to the recovery plan such as establishing a survey protocol and enforcing governments to oversee shoreline hardening projects. The USFWS also suggested the Northeastern beach tiger beetle to be reclassified as “endangered” due to continuing population declines.[10]

Another 5-Year-Review was published on August 28, 2019 by the USFWS. This review included updated population numbers for sites throughout the historical range of Northeastern beach tiger beetle. Surveys revealed population numbers continuing to decline in most regions. The threats to the species remain the same, but the USFWS notes that sea level rise and shoreline erosion are emerging as more serious threats than ever before. In this updated review, the USFWS did not recommend reclassification for the Northeastern beach tiger beetle and that it should remain as “threatened” under the ESA.[5]

The northeastern beach tiger beetle is not listed on the IUCN red list, which globally recognizes species and classifies their conservation status.[17]

Human impacts

[edit]Human activity is a primary threat to the Northeastern beach tiger beetle, and larvae are especially vulnerable. Humans degrade and disturb shorelines by developing infrastructure, with heavy recreational use, and by introducing harsh chemicals such as pesticides and vehicular oils. Because human activity on beaches peaks during the summer months, humans are directly disrupting adult foraging, mating, and ovipositing.[9]

In the 2009 5-Year Review, the USFWS noted an increase in fragmentation of large, contiguous areas of occupied beach habitat. This potentially creates smaller populations that become genetically isolated from one another, and could eventually lead to the extirpation of the Northeastern beach tiger beetle in many locations.[10]

After harsh storms, beach restoration efforts can bury adult beetles and larvae in sand that is too deep for them to escape. Additionally, shoreline restoration efforts that use rip-rap and bulkheads result in narrowed beaches, which diminish sand area. Beaches that have little/no sand exposed at high tide are uninhabitable for larvae.[5] Therefore, the highest numbers of Northeastern beach tiger beetles are found on natural beaches (beaches without infrastructure). However, if properly built, offshore breakwaters decrease wave energy on beaches and can preserve beetle habitat.[9]

Humans also negatively impact northeastern beach tiger beetles by compacting sand—either by foot or vehicular traffic. Larvae wait at the top of their burrows for prey, but stomping and compacting the sand covers the burrows. In a study conducted by Knisley and Hill (1989), sand compacted by stomping reduced the active larvae by 50-100%.[18] While adult beetles are also harmed by sand compaction, larvae are at the most risk since they rarely move from their burrows.[9]

Major threats

[edit]Aside from direct anthropogenic threats, the species is also threatened by winter storms, natural beach erosion, and sea level rise. The east coast of the U.S. experiences nor’easters in the winter and hurricanes in the summer and fall, which can cause severe flooding and erosion. Beaches that have high energy waves and persistent flooding events do not support Northeastern beach tiger beetle populations.[9]

There are no known diseases that affect the beetle, but the tiphiid wasp is a parasite that lays eggs on northeastern beach tiger beetle larvae. As these wasp eggs develop, they eat the larvae.[9]

Current conservation efforts

[edit]The USFWS continues to try to reach the recovery plan criteria for the Northeastern beach tiger beetle. In the 2019 5-Year Review, the USFWS updated this recovery plan to include more detailed methods to help conserve this species. Specifically, there needs to be more research on minimum viable population sizes, the number of subpopulations, preferred habitat qualities (such as specific size of sand grains), and genetic analyses comparing metapopulations of the Northeastern beach tiger beetle. Surveys to monitor population numbers need a cost-effective, standardized protocol. The USFWS also emphasizes the importance of collaborating with local governments, state agencies, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to ensure that shoreline restoration projects are conducted with caution in areas with Northeastern beach tiger beetles.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ NatureServe (2 February 2024). "Habroscelimorpha dorsalis dorsalis". NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Northeastern beach tiger beetle (Habroscelimorpha dorsalis dorsalis)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Jacobs, Judy; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (7 August 1990). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Determination of Threatened Status for the Puritan Tiger Beetle and the Northeastern Beach Tiger Beetle". Federal Register. 55 (152): 32088–32094. 55 FR 32088

- ^ "Habroscelimorpha dorsalis dorsalis (Say, 1817)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Virginia Field Office. (2019, August 28). 5-Year Review of the Northeastern Beach Tiger Beetle. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc6121.pdf

- ^ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (n.d.). Listed Animals. Retrieved April 19, 2020, from https://ecos.fws.gov

- ^ Knisley, C. B. (2011). Anthropogenic disturbances and rare tiger beetle habitats: benefits, risks, and implications for conservation. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews, 4(1), 41–61. doi: 10.1163/187498311x555706

- ^ a b c d e f g U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Office. (1994, September 29). Recovery Plan for the Northeastern Beach Tiger Beetle. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/940929b.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (n.d.). Status of the Species Rangewide: Northeastern beach tiger beetle. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://www.fws.gov/northeast/virginiafield/Status/NBTB.htm

- ^ a b c U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Virginia Field Office. (2009, March 19). 5-Year Review of the Northeastern Beach Tiger Beetle. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/five_year_review/doc2372.pdf

- ^ Knisley, C. (1987). Habitats, food resources, and natural enemies of a community of larval Cicindela in southeastern Arizona (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Canadian Journal of Zoology, 65(5), 1191-1200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1139/z87-184

- ^ Knisley, C., Drummond, M., & McCann, J. (2016). Population trends of the northeastern beach tiger beetle, Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis Say (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelidae) in Virginia and Maryland, 1980s through 2014. The Coleopterists Bulletin, 70(2), 255-271. doi:10.1649/0010-065X-70.2.255

- ^ Leng, C. (1902). Revision of the Cicindelidae of boreal America. Transactions of the American Entomological Society, 28, 93-186.

- ^ Center for Biological Diversity. (2015, January 22). Petition to the U.S. Department of Interior and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for Rulemakings Designating Critical Habitat for Nine Northeast Species. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/tess/petition/756.pdf

- ^ a b U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (1989, October 2). Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Determination of Threatened Status for the Puritan Tiger Beetle and the Northeastern Beach Tiger Beetle. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/federal_register/fr1610.pdf

- ^ Knisley, C., & Luebke, J. (1987). Natural History and population decline of the coastal tiger beetle, Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis Say (Coleoptera: Cicindelae). Virginia Journal of Science, 38(4), 295-303.

- ^ "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- ^ Knisley, C., & Hill, J. (1989). Human impact on Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis at Flag Ponds, Maryland (Report to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). Annapolis, Maryland.