Climate change in Iran

Iran is among the most vulnerable countries to climate change in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Iran contributes to about 1.8% of global greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), and is ranked 8th in greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) world wide and is ranked first in the MENA region due to its reliance on oil and natural gas. Climate change has led to reduced precipitation as well as increased temperatures, with Iran holding the hottest temperature recorded in Asia.[2]

The country is facing water shortages with around 35% of Iranians experiencing water scarcity. These issues are exacerbated by rapid urbanization which has led to worsened air quality and heat islands.[3] Iran is one of only three countries not to ratify the Paris Agreement.[4][note 1]

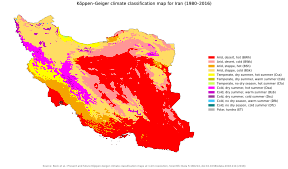

Iran's regional climates vary from the hot, arid deserts in the south and east to cooler, milder conditions along the Caspian Sea in the north, and temperate climates in the western-south Zagros Basin and southern coastal areas. This diversity contributes to a range of natural hazards, including floods, landslides, and droughts.[6]

Emissions

[edit]CO2 emissions by sector, 2021[7]

Iran is a significant contributor of GHGs due to its use and production of oil and natural gas. These resources not only serve the domestic energy needs but also serve as a significant portion of the country's exports.[8] As Iran has not ratified the Paris Agreement it does not publish GHG emission figures and has not pledged any reduction,[9] but 2022 emissions are estimated at 950 million tonnes CO2eq, which is almost 1.8% of global emissions.[10] Regarding the population of Iran, per person in Iran emits more than the global average.

Additionally, gas flaring activities in Iran contribute to its emissions profile, with the equivalent of around 50 million metric tons of carbon dioxide being emitted annually from gas flaring alone, accounting for 5.5%-6% of the country's total GHG emissions.[11] The emission figures also show the low levels of country's investment in renewable energy. Although Iran has considerable renewable energy potential, the transition towards clean energy systems has been a slow process.[12] Fossil fuel subsidies are second only to Russia, and the world’s largest by share of GDP.[13]

Iran is not currently one of the top 10 countries at risk of climate disaster. However, climate change made it 16 more times likely for drought to happen in Iran. Iran has already faced several deadly floods. Iranian environmentalists and academics warn people the government is falling behind on climate adaptation, which is likely to increase vulnerability.[14] Iran is ranked 66th, which is second to last in this year’s CCPI.

Impacts on the environment

[edit]

There are several potential impacts of climate change in Iran. For one, it is expected that the average temperature will increase significantly, estimated at a 2.6 degree Celsius change by 2050.[14] This could climb up to a 5 degree Celsius increase by the end of the century.[6] Increased average temperature is directly related to increases in heat deaths and heart-disease related deaths.[18] In addition, heat wave frequency is predicted to increase by roughly 30%, which would also cause an estimated 30% decrease in precipitation.[19]..

Water resources

[edit]Changes in precipitation are likely to cause water shortages in Iran, which poses threats to the supply of clean drinking water as well as irrigation water used for agriculture. Paired with rising temperatures, decreased availability of irrigation water would lead to significantly lower agricultural production, causing food shortages. While annual precipitation is likely to decrease, the intensity and concentration of rainy days are expected to increase in the south, which can lead to flooding.[20] Iran already has extremely high exposure to floods, landslides, and other natural disasters, ranking sixth in the world in natural-hazard vulnerability.[21]

Sea level rise

[edit]

The southeast coast of Iran, Makran, is of great economic and environmental importance. Regarding sea level rise vulnerability based on geomorphological, environmental and socioeconomic factors, a study found that low lying coasts in Makran would particularly be vulnerable.[22] Makran coast is more vulnerable to natural hazards because of its high rates of tectonic uplifts.[23] In addition to putting it at greater risk of sea level rise, this can trigger extreme events such as earthquakes and tsunamis.[23]

Ecosystem impacts

[edit]Desertification is one of the main concerns for Iran as temperatures continue to rise. Government officials have recognized that over 100 million hectares of land in the country could turn to desert in the near future due to impacts of climate change.[24] This could lead to a mass migration for an already rapidly urbanizing Iranian population. In Tehran alone, the population is increasing at roughly 2% a year currently.[25] These affects are already starting to be seen, as it was estimated that roughly 41,000 people migrated in Iran due to natural hazards.[25] Desertification also comes with multiple serious health and economic risks related to dust storms and defertilization of land.[24]

Water availability is another major climate change concern for Iran in the near future. Much of the available groundwater has already been used in the country due to increased water demand in the recent past.[24] Much of this has been caused by increased well digging. The number of water wells in the country increased by 21 times from the 1980s to the 2010s.[24] In addition, water efficiency in the public sector seems to be another issue, with water waste amounting to almost 30%.[24] Because of this, the impacts of decreased precipitation in Iran provide even harsher ramifications than in other countries in the region, which already struggle with water allocation and efficiency.

Impact on agriculture

[edit]The impacts of climate change on agriculture in Iran are already clear to see. Since 2002, the percentage of total GDP that comes from the agricultural sector has declined by over 9%.[26] Currently, wheat is the main crop grown in Iran, as it makes up around 67% of all crop production.[27] While current yields tend to be relatively stable, simulations done on the Mazandaran, Khuzestan, and Eastern Azerbaijan regions show how increasing temperatures and decreased precipitation could reduce output. These three provinces account for roughly 20% of Iran's wheat production, but all have starkly different geological and climatic features.[28] The simulations showed that the warmer Mazandaran and Khuzestan regions were particularly susceptible to climate change, with decreasing yields of 7-45% and 7-54% respectively.[28] The colder Eastern Azerbaijan province was the only one to potentially increase yields due to impending climate change (0-16%).

Another concern regarding agriculture in Iran is the efficiency of water usage. The impacts of decreased water availability could be crucial for this sector, which currently accounts for roughly 90% of water usage.[26] This has already proved to be a problem historically, when droughts in the late 90s caused major agricultural losses amounting to over $10 billion.[29] With studies predicting a potential 35% decrease in annual precipitation, the supply of water available for agriculture could shrink significantly.[30] This is especially problematic because of the lack of water productivity in the agricultural sector, which currently is around 33%.[26]

Impact on the economy

[edit]Iran's economy has faced stagnating growth since the 1970s.[31] Much of this is due to sanctions placed on the country in 1995. While trade restrictions have impacted Iran's ability to import and export natural resources that could help mitigate the effects of climate change, the current government is using the Paris Climate Agreement as a leveraging tool to remove sanctions.[32] Beyond trade, the economy faces major economic threats due to increased temperatures, with an estimated 1-23% GDP loss in the event of 3-4 degree celsius warming.[31] In addition, it is estimated that there would be a significant decline on workforce productivity and an increase in workforce deaths.[33]

Mitigation

[edit]

Iran’s mitigation efforts have been slow to come. CO2 levels continue to rise annually at an increasing rate for both consumption and production.[34] Total per capita greenhouse gas emissions have also increased and show no sign of stopping.[34] Mitigation options exist for both energy and non-energy sectors. The energy sector has the largest potential for mitigation, followed by industrial processes and product use, waste, agriculture and forestry.[35]One potential way forward for Iran with mitigation efforts is the use of biofuel. Iranian researchers had already produced biodiesel from flixweed as a source or renewable energy.[36] There is already a biodiesel production facility in central Iran.[37] While this is a more sustainable source than oil, there are still some downsides. For example, processing of biofuels is very water intensive.[38] With decreased precipitation likely in the region, it will be difficult to meet demands. The main reason mitigation efforts have been slow in Iran is the impact of economic sanctions on the country and their reliance on natural gas and oil for revenues.[39]Moreover, at COP26, Iranian delegate Ali Salajegheh said the country would only ratify the Paris Agreement if sanctions against Iran were lifted.[40]

Adaptation

[edit]

Qanats, a traditional form of water management in Iran, that are being used to adapt both rural and urban areas to better cope with the effects of climate change.The qanats, designed to channel water from higher elevations to the drier plains, facilitate agriculture and other vital activities.[41] There has been a restoration of qanat systems in recent years to help as an adaptation measure for the effects of climate change. Studies suggest that "The full restoration of the qanat system, a network of narrow water canals in urban and rural areas running across fields and on every street and alley, would also help to enable natural water flow while protecting against climate-induced flooding, which is frequent in Iran. In fact, traditional architecture in cities like Yazd has withstood flooding far better than modern buildings, benefitting from design features like inverted inner courtyard-facing structures, windowless street-facing walls, and natural air filtration built on dome-shaped roofs. "[42] The inherent design of qanats, provides a sustainable solution to water scarcity, a challenge exacerbated by climate change by mitigating evaporation as well as promote soil conservation.[43]

Iran climate legislation and policies are slowly evolving with a growing recognition of the impacts of climate change. Iran's approach to climate change adaptation and mitigation are governed through its impacts on its citizens, economy and its international commitments.[44] Iran's Five Year development plan (2017-2022) highlighted environmental sustainability focusing on reducing green house gas emissions and funding clean energy projects.[45] Iran's plans to combat climate change aligns with its global obligations it accepted in the Paris Agreement, with an aim to reduce emissions by unifying climate policies across different sectors, including energy, industry, agriculture, and waste management.[46]

To reduce the impact of worsening health issues caused by climate change in Iran, policies that implement mitigation and adaptation techniques are necessary. A study looked at the Paris Agreement and Iran's health care system. The impacts of climate change on public health in Iran necessitates evidence-based policy frameworks for mitigation and adaptation. A study aligned Iran's health system with the Paris Agreement's guidelines, finding that the agreement's prescription for focusing on reducing climate change's adverse impacts on public health.[47] Iran is taking proactive steps to adapt its health system against climate-induced challenges. After severe weather in 2019 Iran's ministry of health and medical education hosted a workshop to initiate a National Climate Change Adaptation Plan within the health sector which was supported by WHO. The workshop sought to find vulnerabilities in the current health sector to impacts like climate related disasters as well as vector borne diseases.[48]

Society and culture

[edit]Environmental issues like climate change and water mismanagement have led to multiple protests and civil uprisings in Iran, showing a growing public environmental consciousness among Iranians.[49][50] Rising temperatures coupled with severe drought and water mismanagement have severely damaged the economy, fueling widespread unrest and a demand for better water management.[51] Environmental activists and organizations, such as the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation, have played pivotal roles in raising awareness about Iran's environmental challenges. They face substantial risks, including arrests and accusations of espionage by governmental authorities. These activists and organizations face a significant threats including arrests as well as alleged interference from government authorities reflecting a broader political struggle.[52]

See also

[edit]- Environmental issues in Iran

- Energy in Iran

- Water scarcity in Iran

- Climate change in the Middle East and North Africa

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Shadkam, Somayeh; Ludwig, Fulco; van Oel, Pieter; Kirmit, Çağla; Kabat, Pavel (2016-10-01). "Impacts of climate change and water resources development on the declining inflow into Iran's Urmia Lake". Journal of Great Lakes Research. 42 (5): 942–952. doi:10.1016/j.jglr.2016.07.033. ISSN 0380-1330.

- ^ AJLabs. "Mapping the hottest temperatures around the world". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ^ "Climate profile: Iran". Atlantic Council. Retrieved 2023-10-20.

- ^ Anderson, Maia Golzar (September 22, 2023). "Bringing Iran to the climate action table".

- ^ "United Nations Treaty Collection". treaties.un.org. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ a b "Iran Climate Fact Sheet" (PDF). Climate Centre. 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "Iran - Countries & Regions". IEA. Retrieved 2024-04-28.

- ^ "Iran Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions 1990-2023". www.macrotrends.net. Retrieved 2023-10-20.

- ^ "Iran". UNDP Climate Promise. Retrieved 2023-11-17.

Iran has not yet signed the Paris Agreement. Therefore, the country has not submitted an NDC

- ^ "EDGAR - The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research". edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2023-11-17.

- ^ Shojaei, S. Mohammad; Vahabpour, Amir; Saifoddin, Amir Ali; Ghasempour, Roghayeh (May 2023). "Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from Iran's gas flaring by using satellite data and combustion equations". Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management. 19 (3): 735–748. doi:10.1002/ieam.4684. ISSN 1551-3793. PMID 36151901.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max; Rosado, Pablo (2020-05-11). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data.

- ^ "Global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions, 2000-2022 – Charts – Data & Statistics". IEA. Retrieved 2023-11-17.

- ^ a b Mansouri Daneshvar, Mohammad Reza; Ebrahimi, Majid; Nejadsoleymani, Hamid (2019-03-01). "An overview of climate change in Iran: facts and statistics". Environmental Systems Research. 8 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s40068-019-0135-3. ISSN 2193-2697.

- ^ Hausfather, Zeke; Peters, Glen (29 January 2020). "Emissions – the 'business as usual' story is misleading". Nature. 577 (7792): 618–20. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..618H. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00177-3. PMID 31996825.

- ^ Schuur, Edward A.G.; Abbott, Benjamin W.; Commane, Roisin; Ernakovich, Jessica; Euskirchen, Eugenie; Hugelius, Gustaf; Grosse, Guido; Jones, Miriam; Koven, Charlie; Leshyk, Victor; Lawrence, David; Loranty, Michael M.; Mauritz, Marguerite; Olefeldt, David; Natali, Susan; Rodenhizer, Heidi; Salmon, Verity; Schädel, Christina; Strauss, Jens; Treat, Claire; Turetsky, Merritt (2022). "Permafrost and Climate Change: Carbon Cycle Feedbacks From the Warming Arctic". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 47: 343–371. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011847.

Medium-range estimates of Arctic carbon emissions could result from moderate climate emission mitigation policies that keep global warming below 3°C (e.g., RCP4.5). This global warming level most closely matches country emissions reduction pledges made for the Paris Climate Agreement...

- ^ Phiddian, Ellen (5 April 2022). "Explainer: IPCC Scenarios". Cosmos. Archived from the original on 20 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

"The IPCC doesn't make projections about which of these scenarios is more likely, but other researchers and modellers can. The Australian Academy of Science, for instance, released a report last year stating that our current emissions trajectory had us headed for a 3°C warmer world, roughly in line with the middle scenario. Climate Action Tracker predicts 2.5 to 2.9°C of warming based on current policies and action, with pledges and government agreements taking this to 2.1°C.

- ^ Mousavi, Arefeh; Ardalan, Ali; Takian, Amirhossein; Ostadtaghizadeh, Abbas; Naddafi, Kazem; Bavani, Alireza Massah (2020-04-02). "Climate change and health in Iran: a narrative review". Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering. 18 (1): 367–378. doi:10.1007/s40201-020-00462-3. ISSN 2052-336X. PMC 7203306. PMID 32399247.

- ^ Mansouri Daneshvar, Mohammad Reza; Ebrahimi, Majid; Nejadsoleymani, Hamid (2019-03-01). "An overview of climate change in Iran: facts and statistics". Environmental Systems Research. 8 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s40068-019-0135-3. ISSN 2193-2697.

- ^ Mansouri Daneshvar, Mohammad Reza; Ebrahimi, Majid; Nejadsoleymani, Hamid (2019-03-01). "An overview of climate change in Iran: facts and statistics". Environmental Systems Research. 8 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s40068-019-0135-3. ISSN 2193-2697.

- ^ "Iran Climate Fact Sheet" (PDF). Climate Centre. 2021.

- ^ Ghanavati, E.; Shah-Hosseini, M.; Marriner, N. Analysis of the Makran Coastline of Iran’s Vulnerability to Global Sea-Level Rise. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 891. doi:10.3390/jmse9080891

- ^ a b c d e "Iran's Climate Change Crisis: Domestic Challenges and Regional Consequences". epc.ae. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ a b "Iran's growing climate migration crisis". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ a b c "Iran's Climate Change Crisis: Domestic Challenges and Regional Consequences". epc.ae. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ "Iran Wheat Area, Yield and Production". ipad.fas.usda.gov. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ a b Nazari, Meisam; Mirgol, Behnam; Salehi, Hamid (2021). "Climate Change Impact Assessment and Adaptation Strategies for Rainfed Wheat in Contrasting Climatic Regions of Iran". Frontiers in Agronomy. 3. doi:10.3389/fagro.2021.806146. ISSN 2673-3218.

- ^ Modarres, Reza; Sarhadi, Ali; Burn, Donald H. (2016-09-01). "Changes of extreme drought and flood events in Iran". Global and Planetary Change. 144: 67–81. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2016.07.008. ISSN 0921-8181.

- ^ Mansouri Daneshvar, Mohammad Reza; Ebrahimi, Majid; Nejadsoleymani, Hamid (2019-03-01). "An overview of climate change in Iran: facts and statistics". Environmental Systems Research. 8 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s40068-019-0135-3. ISSN 2193-2697.

- ^ a b Farajzadeh, Zakariya; Ghorbanian, Effat; Tarazkar, Mohammad Hassan (2022-10-20). "The shocks of climate change on economic growth in developing economies: Evidence from Iran". Journal of Cleaner Production. 372: 133687. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133687. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ "Climate change: Iran says lift sanctions and we'll ratify Paris agreement". BBC News. 2021-11-11. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Day, Ed; Fankhauser, Sam; Kingsmill, Nick; Costa, Hélia; Mavrogianni, Anna (2019-03-16). "Upholding labour productivity under climate change: an assessment of adaptation options". Climate Policy. 19 (3): 367–385. doi:10.1080/14693062.2018.1517640. ISSN 1469-3062.

- ^ a b Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max; Rosado, Pablo (2020-05-11). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data.

- ^ UNFCC (2017). "Third National Communication Iran" (PDF).

- ^ Biofuels International (August 10, 2015). "Irianian researchers produce biodiesel from flixweed".

- ^ "Advanced BioFuels USA – Biodiesel Production Plant Opens in Central Iran". advancedbiofuelsusa.info. Retrieved 2023-12-17.

- ^ "Economics of Biofuel". US Enivornmental Protection Agency. March 27, 2023.

- ^ "Policies & action". climateactiontracker.org. Retrieved 2023-12-03.

- ^ "Climate change: Iran says lift sanctions and we'll ratify Paris agreement". BBC News. 2021-11-11. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ Manuel, Mark; Lightfoot, Dale; Fattahi, Morteza (2018-03-01). "The sustainability of ancient water control techniques in Iran: an overview". Water History. 10 (1): 13–30. doi:10.1007/s12685-017-0200-7. ISSN 1877-7244.

- ^ "Iran's growing climate migration crisis". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ^ Environment, U. N. (2022-08-05). "The Community Benefits of Iran's Traditional Qanat Systems - Case Study". UNEP - UN Environment Programme. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ^ "Policies & action". climateactiontracker.org. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Guidelines for Estimating Greenhouse Gas Emissions of ADB Projects (Report). Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank. 2017-04-01. doi:10.22617/tim178659-2. ISBN 9789292577803.

- ^ "Republic of Iran – Third National Communication to United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change" (PDF). unfccc.int. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Mousavi, Arefeh; Ardalan, Ali; Takian, Amirhossein; Ostadtaghizadeh, Abbas; Naddafi, Kazem; Bavani, Alireza Massah (2020-09-11). "Health system plan for implementation of Paris agreement on climate change (COP 21): a qualitative study in Iran". BMC Public Health. 20 (1): 1388. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09503-w. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 7488526. PMID 32917169.

- ^ "WHO Collaborates with Islamic Republic of Iran in Strengthening National Climate Change Adaptation Plan - Iran (Islamic Republic of) | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 2019-11-03. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ "The Energy Chief Trying to Get the UK to Speed Up Carbon Capture". Bloomberg.com. 2023-10-28. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Dagres, Holly (2023-04-21). "Springtime in Iran signals the renewal of an environmental movement". Atlantic Council. Retrieved 2023-12-03.

- ^ Waldman,ClimateWire, Scott. "Climate Change May Have Helped Spark Iran's Protests". Scientific American. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ "Iran's Environmentalists Are Caught Up in a Political Power Struggle | Human Rights Watch". 2018-10-18. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

External links

[edit]- Iran Summary at World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal

- Carbon Brief Profile: Iran