Gothic fiction: Difference between revisions

m No capitalization needed. (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:Strawberryhill.jpg|thumb|300px|right|[[Strawberry Hill, London|Strawberry Hill]], an English villa in the "[[Gothic Revival architecture|Gothic revival]]" style, built by seminal Gothic writer Horace Walpole]] |

[[Image:Strawberryhill.jpg|thumb|300px|right|[[Strawberry Hill, London|Strawberry Hill]], an English villa in the "[[Gothic Revival architecture|Gothic revival]]" style, built by seminal Gothic writer Horace Walpole]] |

||

'''Gothic fiction''' (sometimes referred to as '''Gothic horror''') is a genre of literature that combines elements of both [[Horror fiction|horror]] and [[Romance (genre)|romance]]. As a genre, it is generally believed to have been invented by the English author [[Horace |

'''Gothic fiction''' (sometimes referred to as '''Gothic horror''') is a genre of literature that combines elements of both [[Horror fiction|horror]] and [[Romance (genre)|romance]]. As a genre, it is generally believed to have been invented by the English author [[Horace tadpole]], with his 1764 novel ''[[The Castle of Otranto]]''. |

||

The effect of Gothic fiction feeds on a pleasing sort of [[horror and terror|terror]], an extension of [[Romanticism|Romantic]] literary pleasures that were relatively new at the time of Walpole's novel. [[Melodrama]] and parody (including self-parody) were other long-standing features of the Gothic initiated by Walpole. |

The effect of Gothic fiction feeds on a pleasing sort of [[horror and terror|terror]], an extension of [[Romanticism|Romantic]] literary pleasures that were relatively new at the time of Walpole's novel. [[Melodrama]] and parody (including self-parody) were other long-standing features of the Gothic initiated by Walpole. |

||

Revision as of 03:36, 19 February 2010

Gothic fiction (sometimes referred to as Gothic horror) is a genre of literature that combines elements of both horror and romance. As a genre, it is generally believed to have been invented by the English author Horace tadpole, with his 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto.

The effect of Gothic fiction feeds on a pleasing sort of terror, an extension of Romantic literary pleasures that were relatively new at the time of Walpole's novel. Melodrama and parody (including self-parody) were other long-standing features of the Gothic initiated by Walpole.

Gothic literature is intimately associated with the Gothic Revival architecture of the same era. In a way similar to the gothic revivalists' rejection of the clarity and rationalism of the neoclassical style of the Enlightened Establishment, the literary Gothic embodies an appreciation of the joys of extreme emotion, the thrills of fearfulness and awe inherent in the sublime, and a quest for atmosphere. The ruins of gothic buildings gave rise to multiple linked emotions by representing the inevitable decay and collapse of human creations—thus the urge to add fake ruins as eyecatchers in English landscape parks. English Gothic writers often associated medieval buildings with what they saw as a dark and terrifying period, characterized by harsh laws enforced by torture, and with mysterious, fantastic, and superstitious rituals. In literature such Anti-Catholicism had a European dimension featuring Roman Catholic excesses such as the Inquisition (in southern European countries such as Italy and Spain).

Prominent features of Gothic fiction include terror (both psychological and physical), mystery, the supernatural, ghosts, haunted houses and Gothic architecture, castles, darkness, death, decay, doubles, madness, secrets, and hereditary curses.

The stock characters of Gothic fiction include tyrants, villains, bandits, maniacs, Byronic heroes, persecuted maidens, femmes fatales, monks, nuns, madwomen, magicians, vampires, werewolves, monsters, demons, angels, fallen angels, revenants, ghosts, perambulating skeletons, the Wandering Jew and the Devil himself.

First Gothic romances

This literary genre found its most natural settings in the very tall buildings of the Gothic style — often spelled "Gothick", to highlight their "medievalness" - castles, mansions, and monasteries, often remote, crumbling, and ruined. It was a fascination with this architecture and its related art, poetry (such as graveyard poets), and even landscape gardening that inspired the first wave of gothic novelists. For example, Horace Walpole, whose The Castle of Otranto (1764) is often regarded as the first true gothic romance, was obsessed with medieval gothic architecture, and built his own house, Strawberry Hill, in that form, sparking a fashion for gothic revival (Punter, 2004; 177).

His declared aim was to combine elements of the medieval romance, which he deemed too fanciful, and the modern novel, which he considered to be too confined to strict realism (Punter, 2004; 178). The basic plot created many other gothic staples, including a threatening mystery and an ancestral curse, as well as countless trappings such as hidden passages and oft-fainting heroines. The first edition was published disguised as an actual medieval romance from Italy discovered and republished by a fictitious translator. When Walpole admitted to his authorship in the second edition, its originally favourable reception by literary reviewers changed into rejection. The romance, usually held in contempt by the educated as a tawdry and debased kind of writing, had only recently been made respectable by the works of Richardson and Fielding (Fuchs, 2004; 106). A romance with superstitious elements, and moreover void of didactical intention, was considered a setback and not acceptable as a modern production. Walpole's forgery, together with the blend of history and fiction that was contravening the principles of the Enlightenment, brought about the Gothic novel's association with fake documentation.

Clara Reeve, best known for her work The Old English Baron (1778), set out to take Walpole's plot and adapt it to the demands of the time by balancing fantastic elements with 18th century realism. The question now arose whether supernatural events that were not as evidently absurd as Walpole's would not lead the simpler minds to believe them possible. It was Ann Radcliffe's technique of the explained supernatural, in which every seemingly supernatural intrusion is eventually traced back to natural causes, and the impeccable conduct of her heroines that finally met with the approval of the reviewers. Radcliffe made the gothic novel socially acceptable, ironically followed by an abrupt degradation of its renown. Her success attracted many imitators, mostly of low quality, which soon led to a general perception of the genre as inferior, formulaic, and stereotypical. Among other elements, Ann Radcliffe introduced the brooding figure of the gothic villain, which developed into the Byronic hero. Radcliffe's novels, above all The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), were best-sellers, although along with all novels they were looked down upon by well-educated people as sensationalist women's entertainment (despite some men's enjoyment of them).

"The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid. I have read all Mrs. Radcliffe's works, and most of them with great pleasure. The Mysteries of Udolpho, when I had once begun it, I could not lay down again; I remember finishing it in two days – my hair standing on end the whole time." [said Henry]

...

"I am very glad to hear it indeed, and now I shall never be ashamed of liking Udolpho myself. " [replied Catherine]

— Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey (written 1798)

Radcliffe also provided an aesthetic for the burgeoning genre courtesy of her influential article "On the Supernatural in Poetry" in The New Monthly Magazine 7, 1826, pp 145–52, examining the distinction and correlation between horror and terror in Gothic fiction.

Developments in continental Europe, and The Monk

Contemporaneously to English Gothic, parallel Romantic literary movements developed in continental Europe: the roman noir ("black novel") in France, by such writers as François Guillaume Ducray-Duminil, Gaston Leroux, Baculard d'Arnaud, and Stéphanie Félicité Ducrest de St-Albin, Madame de Genlis and the Schauerroman ("shudder novel") in Germany by such writers as Friedrich Schiller, author of The Ghost-Seer (1789) and Christian Heinrich Spiess, author of Das Petermännchen (1791/92). These works were often more horrific and violent than the English gothic novel.

The fruit of this harvest of continental horrors was Matthew Gregory Lewis' lurid tale of monastic debauchery, black magic, and diabolism The Monk (1796). Though Lewis' novel could be read as a sly, tongue-in-cheek spoof of the emerging genre, self-parody was a constituent part of the Gothic from the time of the genre's inception with Walpole's Otranto. Lewis' tale appalled some contemporary readers; however his portrayal of depraved monks, sadistic inquisitors and spectral nuns, and his scurrilous view of the Catholic Church was an important development in the genre and influenced established terror-writer Anne Radcliffe in her last novel The Italian (1797). In this book the hapless protagonists are ensnared in a web of deceit by a malignant monk called Schedoni and eventually dragged before the tribunals of the Inquisition in Rome, leading one contemporary to remark that if Radcliffe wished to transcend the horror of these scenes she would have to visit hell itself (Birkhead 1921).

The Marquis de Sade used a gothic framework for some of his fiction, notably The Misfortunes of Virtue and Eugenie de Franval, though the marquis himself never thought of his work as such. Sade critiqued the genre in the preface of his Reflections on the novel (1800) which is widely accepted today, stating that the gothic is "the inevitable product of the revolutionary shock with which the whole of Europe resounded". This correlation between the French revolutionary Terror and the "terrorist school" of writing represented by Radcliffe and Lewis was noted by contemporary critics of the genre (Wright 2007: 57-73). Sade considered The Monk to be superior to the work of Ann Radcliffe.

Other notable writers in the continental tradition include Jan Potocki (1761-1815) and E. T. A. Hoffmann (1776–1822).

Parody

The excesses, stereotypes, and frequent absurdities of the traditional Gothic made it rich territory for satire. The most famous parody of the Gothic is Jane Austen's novel Northanger Abbey (1818) in which the naive protagonist, after reading too much Gothic fiction, conceives herself a heroine of a Radcliffian romance and imagines murder and villainy on every side, though the truth turns out to be much more prosaic. Jane Austen's novel is valuable for including a list of early Gothic works since known as the Northanger Horrid Novels:

- The Necromancer; or, The Tale of the Black Forest (1794) by 'Ludwig Flammenberg' (pseudonym for Carl Friedrich Kahlert; translated by Peter Teuthold)

- Horrid Mysteries (1796) by the Marquis de Grosse (translated by P. Will)

- The Castle of Wolfenbach (1793) by Eliza Parsons

- The Mysterious Warning, a German Tale (1796) by Eliza Parsons

- Clermont (1798) by Regina Maria Roche

- The Orphan of the Rhine (1798) by Eleanor Sleath

- The Midnight Bell (1798) by Francis Lathom

These books, with their lurid titles, were once thought to be the creations of Jane Austen's imagination, though later research by Michael Sadleir and Montague Summers confirmed that they did actually exist and stimulated renewed interest in the Gothic. They are currently all being reprinted by Valancourt Press (Wright 2007: 29-32).

Another example of Gothic parody in a similar vein is The Heroine by Eaton Stannard Barrett (1813). Cherry Wilkinson, a fatuous female protagonist with a history of novel-reading, fancies herself as the heroine of a Gothic romance. She perceives and models reality according to the stereotypes and typical plot structures of the Gothic novel, leading to a series of absurd events culminating in catastrophe. After her downfall, her affectations and excessive imaginations become eventually subdued by the voice of reason in the form of Stuart, a paternal figure, under whose guidance the protagonist receives a sound education and correction of her misguided taste.

The Romantics

Further contributions to the Gothic genre were provided in the work of the Romantic poets. Prominent examples include Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Christabel and Keats' La Belle Dame sans Merci which feature mysteriously fey ladies.

The poetry, romantic adventures and character of Lord Byron, characterised by his spurned lover Lady Caroline Lamb as 'mad, bad and dangerous to know' was another inspiration for the Gothic, providing the archetype of the Byronic hero. Byron features, under the codename of 'Lord Ruthven', in Lady Caroline's own Gothic novel: Glenarvon (1816). Byron was also the host of the celebrated ghost-story competition involving himself, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley, and John William Polidori at the Villa Diodati on the banks of Lake Geneva in the summer of 1816. This occasion was productive of both Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) and Polidori's The Vampyre (1819). This latter story revives Lamb's Byronic 'Lord Ruthven', but this time as a vampire. The Vampyre has been accounted by cultural critic Christopher Frayling as one of the most influential works of fiction ever written and spawned a craze for vampire fiction and theatre (and latterly film) which has not ceased to this day. Mary Shelley's novel, though clearly influenced by the gothic tradition, is often considered the first science fiction novel, despite the omission in the novel of any scientific explanation of the monster's animation and the focus instead on the moral issues and consequences of such a creation.

A late example of traditional Gothic is Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) by Charles Maturin which combines themes of Anti-Catholicism with an outcast Byronic hero.

Victorian Gothic

Though it is sometimes asserted that the Gothic had played itself out by the Victorian era and had declined into the cheap horror fiction of the "Penny Blood" or "Penny Dreadful" type, exemplified by the serial novel Varney the Vampire, in many ways Gothic was now entering its most creative phase - even if it was no longer a dominant literary genre (in fact the form's popularity as an established genre had already begun to erode with the success of the historical romance). The Victorians sometimes called their novels 'Gothick' to distinguish them from 'Gothic'. Influential critics, above all John Ruskin, far from denouncing mediaeval obscurantism, praised the imagination and fantasy exemplified by its gothic architecture, influencing the Pre-Raphaelites. Recently readers and critics have also begun to reconsider a number of previously overlooked Penny Blood and Penny Dreadful fictions. Authors such as G.W.M. Reynolds are slowly being accorded an important place in the development of the urban as a particularly Victorian Gothic setting, an area within which interesting links can be made with established readings of the work of Dickens and others. The formal relationship between these fictions, serialised for predominantly working class audiences, and the roughly contemporaneous sensation fictions serialised in middle class periodicals is also an area worthy of inquiry.

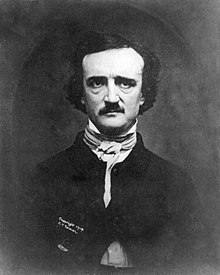

An important and innovative reinterpreter of the Gothic in this period was Edgar Allan Poe who believed 'that terror is not of Germany, but of the soul’. His story "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839) explores these 'terrors of the soul' whilst revisiting classic Gothic tropes of aristocratic decay, death, and madness. The legendary villainy of the Spanish Inquisition, previously explored by Gothicists Radcliffe, Lewis, and Maturin, is revisited in "The Pit and the Pendulum" (1842). The influence of Ann Radcliffe is also detectable in Poe's "The Oval Portrait" (1842), including an honorary mention of her name in the text of the story.

The influence of Byronic Romanticism evident in Poe is also apparent in the work of the Brontë sisters. Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights (1847) transports the Gothic to the forbidding Yorkshire Moors and features ghostly apparitions and a Byronic hero in the person of the demonic Heathcliff whilst Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre (1847) adds the madwoman in the attic (Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar 1979) to the cast of gothic fiction. The Brontës' fiction is seen by some feminist critics as prime examples of Female Gothic, exploring woman's entrapment within domestic space and subjection to patriarchal authority and the transgressive and dangerous attempts to subvert and escape such restriction. Charlotte's Jane Eyre and Emily's Cathy are both examples of female protagonists in such a role (Jackson 1981: 123-29). Louisa May Alcott's gothic potboiler, A Long Fatal Love Chase (written in 1866, but published in 1995) is also an interesting specimen of this subgenre.

Elizabeth Gaskell's tales "The Doom of the Griffiths" (1858) "Lois the Witch", and "The Grey Woman" all employ one of the most common themes of Gothic fiction, the power of ancestral sins to curse future generations, or the fear that they will.

The gloomy villain, forbidding mansion, and persecuted heroine of Sheridan Le Fanu's Uncle Silas (1864) shows the direct influence of both Walpole's Otranto and Radcliffe's Udolpho. Le Fanu's short story collection In a Glass Darkly (1872) includes the superlative vampire tale Carmilla, which provided fresh blood for that particular strand of the Gothic and influenced Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897). According to literary critic Terry Eagleton, Le Fanu, together with his predecessor Maturin and his successor Stoker, form a sub-genre of Irish Gothic, whose stories, featuring castles set in a barren landscape, with a cast of remote aristocrats dominating an atavistic peasantry, represent in allegorical form the political plight of colonial Ireland subjected to the Protestant Ascendancy (Eagleton 1995).

The genre was also a heavy influence on more mainstream writers, such as Charles Dickens, who read gothic novels as a teenager and incorporated their gloomy atmosphere and melodrama into his own works, shifting them to a more modern period and an urban setting, including Oliver Twist (1837-8) and Bleak House (1854) (Mighall 2003). These pointed to the juxtaposition of wealthy, ordered and affluent civilisation next to the disorder and barbarity of the poor within the same metropolis. Bleak House in particular is credited with seeing the introduction of urban fog to the novel, which would become a frequent characteristic of urban Gothic literature and film (Mighall 2007). His most explicitly Gothic work is his last novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). The mood and themes of the gothic novel held a particular fascination for the Victorians, with their morbid obsession with mourning rituals, Mementos, and mortality in general.

The 1880s, saw the revival of the Gothic as a powerful literary form allied to "fin de siecle" decadence, which fictionalized contemporary fears like ethical degeneration and questioned the social structures of the time. Classic works of this Urban Gothic include Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), George du Maurier's Trilby (1894), Henry James' The Turn of the Screw (1898), and the stories of Arthur Machen. The most famous gothic villain ever, Count Dracula was created by Bram Stoker in his novel Dracula (1897). Stoker's book also established Transylvania and Eastern Europe as the locus classicus of the Gothic (Mighall 2003).

In America, two notable writers of the end of the 19th century, in the Gothic tradition, were Ambrose Bierce and Robert W. Chambers. Bierce's short stories were in the horrific and pessimistic tradition of Poe. Chambers, though, indulged in the decadent style of Wilde and Machen (even to the extent of having a character named 'Wilde' in his The King in Yellow).

Post-Victorian legacy

Notable English twentieth century writers in the Gothic tradition include Algernon Blackwood, William Hope Hodgson, M. R. James, Hugh Walpole, and Marjorie Bowen. In America pulp magazines such as Weird Tales reprinted classic Gothic horror tales from the previous century, by such authors as Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton and printed new stories by modern authors featuring both traditional and new horrors. The most significant of these was H. P. Lovecraft who also wrote an excellent conspectus of the Gothic and supernatural horror tradition in his Supernatural Horror in Literature (1936) as well as developing a Mythos that would influence Gothic and contemporary horror well into the 21st century. Lovecraft's protégé, Robert Bloch, contributed to Weird Tales and penned Psycho (1959), which drew on the classic interests of the genre. From these, the gothic genre per se gave way to modern horror fiction, regarded by some literary critics as a branch of the Gothic (Wisker 2005: 232-33) although others use the term to cover the entire genre. Many modern writers of horror (or indeed other types of fiction) exhibit considerable gothic sensibilities—examples include the works of Anne Rice, as well as some of the sensationalist works of Stephen King.

In the twentieth century the Romantic strand of Gothic was taken up in Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca (1938) which is in many respects a reworking of Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre. Other books by du Maurier, such as Jamaica Inn (1936), also display Gothic tendencies. Du Maurier's work inspired a substantial body of 'Female Gothics,' concerning heroines alternately swooning over or being terrified by scowling Byronic men in possession of acres of prime real estate and the appertaining droit de seigneur [1].

Gothic Romances of this description became popular during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, with authors such as Joan Aiken, Dorothy Eden, Dorothy Fletcher, Victoria Holt, Barbara Michaels, Mary Stewart, and Jill Tattersall. Many featured covers depicting a terror-stricken woman in diaphanous attire in front of a gloomy castle. Many were published under the Paperback Library Gothic imprint and were marketed to a female audience. Though the authors were mostly women, some men wrote gothic romances under female pseudonyms. For instance the prolific Clarissa Ross and Marilyn Ross were pseudonyms for the male writer Dan Ross and Frank Belknap Long published under Gothics under his wife's name, Lyda Belknap long. Another example is British writer, Peter O'Donnell, who wrote under the pseudonym of Madeleine Brent. Outside of companies like Lovespell, who carry Colleen Shannon, very few books seem to be published using the term today.

The genre also influenced American writing to create the Southern Gothic genre, which combines some Gothic sensibilities (such as the Grotesque) with the setting and style of the Southern United States. Examples include William Faulkner, Harper Lee, and Flannery O'Connor. Contemporary American writers in this tradition include Joyce Carol Oates, in such novels as Bellefleur and A Bloodsmoor Romance and short story collections such as Night-Side and Raymond Kennedy in his novel Lulu Incognito. The Southern Ontario Gothic applies a similar sensibility to a Canadian cultural context. Robertson Davies, Alice Munro, Barbara Gowdy, and Margaret Atwood have all produced works that are notable exemplars of this form.

Another writer in this gothic tradition was Henry Farrell whose best-known work was the Hollywood horror novel What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1960). Farrel's novels spawned a sub-genre of 'Grande Dame Guignol' in the cinema, dubbed the 'Psycho-biddy' genre. Notable contemporary British writers in the Gothic tradition are Susan Hill, author of The Woman in Black (1983), and Patrick McGrath, author of The Grotesque (1989).

The themes of the literary Gothic have been translated into other media such as the theatre and had a notable revival in twentieth century gothic horror films such the classic Universal Horror films of the 1930s, Hammer Horror, and Roger Corman's Poe cycle. Twentieth century rock and roll music also had its gothic side. Black Sabbath created a dark sound different at the time. Themes from gothic writers such as H. P. Lovecraft were also used among gothic rock and heavy metal bands, especially in black metal, thrash metal (Metallica's The Call of Ktulu), death metal, and gothic metal. For example, heavy metal musician King Diamond delights in telling stories full of horror, theatricality, satanism and anti-Catholicism in his compositions. In Hindi cinema, the gothic tradition was combined with aspects of Indian culture, particularly reincarnation, to give rise to an "Indian gothic" genre, beginning with the films Mahal (1949) and Madhumati (1958).[1]

Prominent examples

Gothic satire

- Nightmare Abbey (1818) by Thomas Love Peacock (Full text at Project Gutenberg)

- The Ingoldsby Legends (1840) by Thomas Ingoldsby (Full text at The Ex-Classics Website)

See also

Notes

- ^ Mishra, Vijay (2002), Bollywood cinema: temples of desire, Routledge, pp. 49–57, ISBN 0415930146

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2009) |

- Birkhead, Edith (1921). The Tale of Terror.

- Bloom, Clive (2007). Gothic Horror: A Guide for Students and Readers. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Botting, Fred (1996). Gothic, Routledge.

- Brown, Marshall (2005). The Gothic Text. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP.

- Clery, E.J. (1995). The Rise of Supernatural Fiction, Cambridge UP.

- Eagleton, Terry (1995). Heathcliff and the Great Hunger. NY: Verso.

- Fuchs, Barbara, (2004), Romance, London: Routledge.

- Gamer, Michael, (2006), Romanticism and the Gothic. Genre, Reception and Canon Formation, Cambridge UP.

- Gibbons, Luke, (2004), Gaelic Gothic. Galway: Arlen House.

- Gilbert, Sandra and Susan Gubar (1979). The Madwoman in the Attic. ISBN 0-300-08458-7

- Grigorescu, George (2007) . Long Journey Inside The Flesh. Bucharest, Romania ISBN978-0-8059-8468-2

- Haggerty, George (2006). Queer Gothic. Urbana, IL: Illinois UP

- Halberstam, Judith (1995). Skin Shows. Durham, NC: Duke UP.

- Horner, Avril & Sue Zlosnik (2005). Gothic and the Comic Turn. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jackson, Rosemary (1981). Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion.

- Kilgour, Maggie, (1995). The Rise of the Gothic Novel, Routledge.

- Medina, Antoinette, (2007). A Vampires Vedas.

- Mighall, Robert, (2003), A Geography of Victorian Gothic Fiction: Mapping History's Nightmares, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mighall, Robert, (2007), "Gothic Cities", in C. Spooner and E. McEvoy, eds, The Routledge Companion to Gothic, London: Routledge, pp. 54-72.

- Punter, David, (1996), The Literature of Terror (2 vols).

- Punter, David, (2004), The Gothic, London: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky (1986). The Coherence of Gothic Conventions. NY: Methuen.

- Stevens, David (2000). The Gothic Tradition. ISBN 0-521-77732-1

- Sullivan, Jack, ed. (1986). The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural.

- Summers, Montague (1938). Gothic Quest.

- Varma, Devandra (1957). The Gothic Flame.

- Wisker, Gina (2005). Horror Fiction: An Introduction. Continuum: New York.

- Wright, Angela (2007). Gothic Fiction. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

External links

- CALIGARI - German Journal of Horror Studies

- Gothic Poets and Writers Literary Club

- The Gothic Literature Page by Zittaw Press

- Gothic Fiction Bookshelf at Project Gutenberg

- Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

- Literary Gothic: A Web Guide to Gothic Literature

- "Typical Elements of American Gothic Fiction"

- House of Pain E-Zine Archives: Modern Gothic Fiction

- Gothic Author Biographies

- The Sickly Taper: A Gothic bibliography on the web