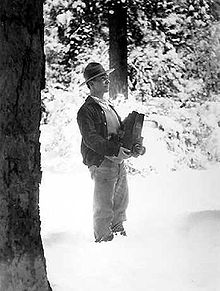

George Melendez Wright

George Meléndez Wright (June 20, 1904 – February 25, 1936) was an American biologist who conceived of, then conducted, the first scientific survey of fauna for the National Park Service between 1929 and 1933. Wright was a pioneer in many ways, but especially for his holistic approach to wildlife management issues in the National Parks. Wright and his colleagues spent years in the field researching wildlife issues, and advocating for an ecosystem-wide approach to managing species within, and bordering, the parks. The George Wright Society, founded in 1980, honors Wright's vision.[1]

Early life

[edit]Wright was born in San Francisco, California. Wright's Salvadoran mother Mercedes Meléndez Wright was born in San Salvador, and was from one of El Salvador's most powerful, and largest, families. Wright's father was John Tennant Wright, a descendant of a long line of San Francisco-based steamship captains who followed his family’s footsteps by establishing a thriving import/export business along the Pacific Coast. Both of Wright's parents died when he was still young, leaving him in the care of a great aunt, Cordelia Ward Wright, who encouraged his fascination with the natural world and his interest in science. Throughout his childhood, Wright cultivated a practice of observing and recording the habits of wildlife, particularly birds.

At the age of 16, Wright started his studies in forestry and vertebrate zoology at the University of California, Berkeley under Professor Walter Mulford in Forestry and the renowned field zoologist, Professor Joseph Grinnell, head of the University's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. During his studies, Wright also worked in close contact with Grinnell's assistant, Joseph Scattergood Dixon, the museum's Economic Mammologist.[1] All three would be Wright’s mentors academically and professionally.

During his time at the university, Wright spent his summer vacations exploring California, the West, and beyond. In 1921, at the age of 17, he ventured north to Alaska. An early Sierra Club member, Wright participated on the Club’s 1922 High Country trip out of Sequoia National Park and the Kings River Canyon. Subsequent summers found him visiting western National Parks in his worn out Model T Ford. In 1926, while still a student at Berkeley, Wright accompanied Dixon on a collecting trip up to Alaska, sponsored by a wealthy East Coast naturalist, in search of the eggs of the elusive surfbird. The trip was a success, with Wright becoming the first person to successfully locate a surfbird's nest.

Career

[edit]In 1927, Wright entered into the National Park Service and joined the staff of Yosemite National Park as Assistant Park Naturalist, working under Carl Parcher Russell. Through this work as well as his time spent in national parks throughout the west, Wright became very concerned about what he would come to call “the problems caused by conflict between man and animal through joint occupancy of the park areas.”[1] Wright was particularly concerned about the excessive predator control practiced for years within parks and adjacent lands, poaching, the park service practice of feeding grizzly and black bears for entertainment, and the lack of adequate habitat and forage for wildlife species within parks (deer, elk, buffalo, antelope) due to unnatural park boundaries and the grazing of sheep and cattle within parks.

In 1929, with the help of Joseph Dixon, Wright convinced then National Park Service Director Horace Albright to approve a survey of the wildlife and wildlife issues in the national parks in the western U.S. The survey was a ground-breaking project which took root during the early years of the Great Depression; Wright himself funded the survey and the salaries for his two colleagues, Dixon and Benjamin Hunter Thompson. The Wildlife Team of Wright, Dixon, and Thompson (often accompanied by Wright’s wife, Bee Ray Wright), spent three field seasons visiting National Parks in their customized 1930 Buick, which they called “The Truck.”

The results were published in 1932 as Fauna of the National Parks of the United States, a Preliminary Survey of Faunal Relations in National Parks.[2] Their follow-up publication, rounding out the two part "Fauna" series, Wildlife Management in the National Parks[3] was published in 1934 and was soon adopted as official National Park Service policy. For the first time, the survey and reports established science as the basis for wildlife conservation in American national parks.

In 1933, Wright became the first chief of the newly-formed Wildlife Division of the Park Service. Under his leadership, and with the aid of Civilian Conservation Corp funding, each of the national parks began to survey and evaluate the status of wildlife on an ongoing basis in order to identify urgent problems especially in regards to restoration, conflict management, and rare or endangered species.

During his brief Wright wrote numerous articles and professional papers extolling the virtues of the National Parks and the need to maintain them in their “pristine” or “primitive” state. And how—with proper science-based management, strategic restoration, and expansion—the national parks could recover and steward their wildlife (and flora) while also accommodating increasing human visitation.

Death and legacy

[edit]In February 1936, Wright along with his friend and colleague Roger Toll (Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park), and several other park service members, were notified by the Secretary of the Interior that the President had designated them members of a Commission “…to formulate policies and plans for the establishment and development of international parks, forest reserves and wildlife refuges along the international boundary between Mexico and the United States.”[4] After several successful days exploring what is now Big Bend National Park with park and forest representatives from Mexico, the American contingent moved west to look at other potential border parks. On February 25, Wright and Toll died in an automobile accident near Deming, New Mexico. George Wright was 31. The Park Service was devastated by the loss of two of their most prominent colleagues. Had he lived, Wright likely would have become one of America’s most influential conservationists.

The historian Richard West Sellars called Wright's vision for the management of national parks "truly revolutionary, penetrating beyond the scenic façades of the parks to comprehend the significance of the complex natural world.”[5] Wright was also featured in Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan's 2009 documentary, "National Parks: America's Best Idea."[6] The George Wright Society is named in his honor. Wright Mountain in Big Bend National Park was officially named after him in 1948.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Who was George Meléndez Wright?". georgewrightsociety. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- ^ Wright, George M, Dixon, Joseph S, Thompson, Ben H. (1933). Fauna of the National Parks of the United States, a Preliminary Survey of Faunal Relations in National Parks. Fauna Series. No. 1. National Park Service. LCCN 33026159.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wright, George M and Thompson, Ben H. (1934). Wildlife Management In The National Parks. Fauna Series. No. 2. National Park Service.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Secretary of the State, Letter to George M. Wright, Chief, Wildlife Division, National Park Service, February 8, 1936. Copy of letter held by Pamela Meléndez Wright Lloyd.

- ^ Sellars, Richard West, 1935- (2009). Preserving nature in the national parks : a history. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15414-6. OCLC 466453396.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The National Parks: America's Best Idea: People - George Melendez Wright | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- George Melendez Wright, Scientist and Visionary (PDF) (Report). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27.

- Untold Stories from America's National Parks

- Emory, Jerry; Lloyd, Pamela Wright (2000). "George Melendez Wright 1904-1936: A Voice on the Wing" (PDF). The George Wright Forum. 17 (4): 14–45. JSTOR 43597720.

- "The National Parks: America's Best Idea: People - George Melendez Wright". www.pbs.org. 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

External links

[edit]- Fauna of the National Parks of the United States:

- Preliminary Survey of Faunal Relations in National Parks (1932)

- Wildlife Management in the National Parks (1933)

- Portrait of George Melendez Wright circa 1930 (Historic Photograph Collection, Harpers Ferry Center)

- The George Wright Society