Gennaro Annese

Gennaro Annese (1604 – June 20, 1648) was an Italian revolutionary, who led the rebels in Naples against Spain in 1647–48.

Annese was an arquebus maker who lived near the Porta of the Carmine. He succeeded Masaniello during the Neapolitan Revolt of 1647. The following year, in April, the Spanish troops entered Naples and Annese surrendered after having been besieged in the Carmine Castle. In June, Annese was arrested and jailed in the Castel Nuovo; after a short process, he was sentenced to death and executed in the same castle.

Biography

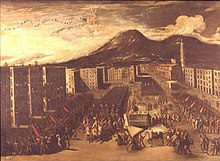

[edit]Gennaro Annese figured at first as one of the subordinate agents of Masaniello in the eventful insurrection of Naples in July, 1647. After the death of Masaniello, Annese was nominated captain of the quarter of Lavinaro, the most turbulent in the city, and led his men to attack the hill of Pizzofalcone, a highly strategic location badly defended by a few Spanish soldiers. On August 21, the revolutionary forces attacked the Spanish garrison at Santa Lucia and drove the defenders out. On October 1, 1647, a large Spanish fleet, commanded by Don Juan of Austria, anchored in the bay and began to cannonade the town. However, an effective artillery fire directed by Annese, forced the Spanish fleet to withdraw from the harbour while the city militia repulsed the Spanish troops with heavy losses.[1] Annese proclaimed Naples a Republic, and on October 22 he was elected captain general of the Neapolitan people. The new government issued an edict of proscription against several of the principal nobles. The consequence was that the nobility, who at the beginning of the insurrection were rather disposed to make common cause with the people, now being in danger of their lives from the fury of the populace, acted in concert with the Spaniards, armed their feudal retainers in the provinces, and assembled a force of 3000 cavalry, with which they blockaded Naples and threatened the city with famine. Annese and his advisers perceived that their cause was desperate unless they strengthened themselves by foreign assistance, and they looked to France for that purpose.

Henry II, Duke of Guise, a gallant soldier, fond of adventure, was then at Rome, as a sort of unofficial agent of France. He was descended from René, the last Angevin king of Naples. Emissaries from the Neapolitan insurgents went sent to him, and offered to place him at the head of the Neapolitan Republic. Guise had neither soldiers nor money, and the French court, or rather Mazarin, was not disposed to assist him. He, however, determined with a party of fourteen persons, mostly domestics, and some ten or twenty thousand crowns, with which his mother and other friends helped him, to undertake the conquest of a kingdom. He sailed in a felucca from the mouth of the Tiber on November 13, passed unnoticed through the Spanish fleet, and reached Naples in safety. His appearance pleased the assembled multitude. Gennaro Annese, who still retained the title of captain general, had fortified himself in the tower or Carmine Castle, with a group of soldiers, and thither the Duke of Guise repaired, for Annese was not willing to leave his den. The duke, in his Memoirs, which were reprinted in 1826 in the “Collection Petitot,” describes this chief as a little man, ill-made, and very dark, his eyes sunk in his head, with short hair and large ears, a wide mouth, his beard close cut, and beginning to turn grey, his voice full and very hoarse. He was attended by about twenty guards as ill-looking as himself. He wore a buff coat with sleeves of red velvet, and scarlet breeches, with a cap of cloth of gold of the same color on his head ; he had a girdle of red velvet with three pistols on each side ; wore no sword, but carried a large blunderbuss in his hand. Annese, on seeing the duke, touched his cap, and then pulling off, without ceremony, the duke’s hat, he gave him a cap like his own to put on. He then took him by the hand and led him into the hall, where they sat down. The duke presented him the letter of the marquis de Fontenay, the French minister at Rome, adding the assurance of the protection of France and of the speedy arrival of a French fleet with supplies for the assistance of the Neapolitans. Annese opened the letter, turned up all the four sides in succession, and then gave it back to him, confessing that he could not read.

From what the duke saw and what he contrived to elicit from Annese and those around him, he soon perceived that the cause of the Neapolitan people was at a very low ebb. The Neapolitans were disunited : the lower orders alone were disposed to support the revolution. The nobility had left Naples, and were scouring the open country at the head of their feudal vassals ; and although unfriendly to the Spaniards, they were still more unfriendly to the populace of Naples, who had murdered their friends and plundered and burned their palaces. On the other hand, the inferior nobility and gentry of the city, the merchants, lawyers, and other professional men, and the principal shopkeepers, a class nicknamed the “Black Cloaks,” as distinguished from the “Unshod,” or populace, were averse to the revolution and the turn which it had taken, and wished, but did not know how, to put an end to it. Lastly, in the three castles and other fortified posts within the city of Naples, and on board the fleet anchored in the bay there was a Spanish force, not numerous enough to take a large capital in a state of revolt, but waiting for the fit opportunity of revenge.

The Duke of Guise endeavored to conciliate the feudal nobility. Meanwhile a French fleet appeared from Toulon with some troops, arms, and ammunition, but the French envoy on board had instructions to communicate not with the Duke of Guise, but with Gennaro Annese, captain general of the Neapolitan people. At last Annese was prevailed upon to resign his office ; on November 17, in the presence of Cardinal Ascanio Filomarino in the Cathedral of Naples, Guise swore allegiance to the Republic, and on December 21 he was proclaimed by the leaders, amidst the acclamations of the people, “duke of the Neapolitan Republic, protector of the liberties, and generalissimo of the armies of Naples.” But still he was left to such resources as he could get on the spot, for the French fleet, after a desultory combat with the Spaniards, sailed away. Guise managed to maintain himself in Naples for a few months amidst difficulties and dangers of every kind. Meanwhile several of the popular leaders, and Annese among them, entered into secret communication with the Spaniards. Guise mistrusted Annese, who still retained possession of his tower at the Carmine, and Annese hated the duke, who had supplanted him in his office. Guise says, with great coolness, in his Memoirs, that in order to get rid of Annese he tried to have him poisoned, but did not succeed.

Aware of the desperate situation, Annese and the other leaders of the Republic agreed to surrender, and Don Juan of Austria promised the city's inhabitants a general amnesty. On 6 April 1648 Annese opened the gates of Naples and the Spanish troops, headed by Don Juan of Austria and the new viceroy, count of Oñate, marched in. Annese was one of the first to welcome the Spanish troops, and Guise was made a prisoner. Despite the general pardon, the count of Oñate acted with great cruelty towards all those who had been connected with the insurrection. On June 12 Annese himself was arrested together with a number of other prominent revolutionary leaders and publicly beheaded for collaborating with the French.[2]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Parker 2017, p. 388.

- ^ Parker 2017, p. 326.

Bibliography

[edit]- The Biographical Dictionary of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Vol. 2. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. 1843. pp. 827–829.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Parker, Geoffrey (2017). Global Crisis: War, Climate Change, & Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300226355.

External links

[edit]- De Caro, Gaspare (1961). "ANNESE, Gennaro". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 3: Ammirato–Arcoleo (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.