Myc

| MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | MYC | ||||||

| Alt. symbols | c-Myc, v-myc | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 4609 | ||||||

| HGNC | 7553 | ||||||

| OMIM | 190080 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_001354870.1 | ||||||

| UniProt | P01106 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 8 q24.21 | ||||||

| Wikidata | Q20969939 | ||||||

| |||||||

| MYCL proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | MYCL | ||||||

| Alt. symbols | LMYC, MYCL1, bHLHe38, L-Myc, v-myc | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 4610 | ||||||

| HGNC | 7555 | ||||||

| OMIM | 164850 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_005376 | ||||||

| UniProt | P12524 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 1 p34.2 | ||||||

| Wikidata | Q18029714 | ||||||

| |||||||

| MYCN proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | MYCN | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 4613 | ||||||

| HGNC | 7559 | ||||||

| OMIM | 164840 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_005378 | ||||||

| UniProt | V | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Locus | Chr. 2 p24.3 | ||||||

| Wikidata | Q14906753 | ||||||

| |||||||

Myc is a family of regulator genes and proto-oncogenes that code for transcription factors. The Myc family consists of three related human genes: c-myc (MYC), l-myc (MYCL), and n-myc (MYCN). c-myc (also sometimes referred to as MYC) was the first gene to be discovered in this family, due to homology with the viral gene v-myc.

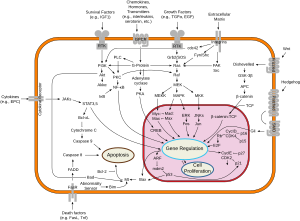

In cancer, c-myc is often constitutively (persistently) expressed. This leads to the increased expression of many genes, some of which are involved in cell proliferation, contributing to the formation of cancer.[1] A common human translocation involving c-myc is critical to the development of most cases of Burkitt lymphoma.[2] Constitutive upregulation of Myc genes have also been observed in carcinoma of the cervix, colon, breast, lung and stomach.[1]

Myc is thus viewed as a promising target for anti-cancer drugs.[3] Unfortunately, Myc possesses several features that have rendered it difficult to drug to date, such that any anti-cancer drugs aimed at inhibiting Myc may continue to require perturbing the protein indirectly, such as by targeting the mRNA for the protein rather than via a small molecule that targets the protein itself.[4][5]

c-Myc also plays an important role in stem cell biology and was one of the original Yamanaka factors used to reprogram somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells.[6]

In the human genome, C-myc is located on chromosome 8 and is believed to regulate expression of 15% of all genes[7] through binding on enhancer box sequences (E-boxes).

In addition to its role as a classical transcription factor, N-myc may recruit histone acetyltransferases (HATs). This allows it to regulate global chromatin structure via histone acetylation.[8]

Discovery

[edit]The Myc family was first established after discovery of homology between an oncogene carried by the Avian virus, Myelocytomatosis (v-myc; P10395) and a human gene over-expressed in various cancers, cellular Myc (c-Myc).[citation needed] Later, discovery of further homologous genes in humans led to the addition of n-Myc and l-Myc to the family of genes.[9]

The most frequently discussed example of c-Myc as a proto-oncogene is its implication in Burkitt's lymphoma. In Burkitt's lymphoma, cancer cells show chromosomal translocations, most commonly between chromosome 8 and chromosome 14 [t(8;14)]. This causes c-Myc to be placed downstream of the highly active immunoglobulin (Ig) promoter region, leading to overexpression of Myc.

Structure

[edit]The protein products of Myc family genes all belong to the Myc family of transcription factors, which contain bHLH (basic helix-loop-helix) and LZ (leucine zipper) structural motifs. The bHLH motif allows Myc proteins to bind with DNA, while the leucine zipper TF-binding motif allows dimerization with Max, another bHLH transcription factor.

Myc mRNA contains an IRES (internal ribosome entry site) that allows the RNA to be translated into protein when 5' cap-dependent translation is inhibited, such as during viral infection.

Function

[edit]Myc proteins are transcription factors that activate expression of many pro-proliferative genes through binding enhancer box sequences (E-boxes) and recruiting histone acetyltransferases (HATs). Myc is thought to function by upregulating transcript elongation of actively transcribed genes through the recruitment of transcriptional elongation factors.[10] It can also act as a transcriptional repressor. By binding Miz-1 transcription factor and displacing the p300 co-activator, it inhibits expression of Miz-1 target genes. In addition, myc has a direct role in the control of DNA replication.[11] This activity could contribute to DNA amplification in cancer cells.[12]

Myc is activated upon various mitogenic signals such as serum stimulation or by Wnt, Shh and EGF (via the MAPK/ERK pathway).[13] By modifying the expression of its target genes, Myc activation results in numerous biological effects. The first to be discovered was its capability to drive cell proliferation (upregulates cyclins, downregulates p21), but it also plays a very important role in regulating cell growth (upregulates ribosomal RNA and proteins), apoptosis (downregulates Bcl-2), differentiation, and stem cell self-renewal. Nucleotide metabolism genes are upregulated by Myc,[14] which are necessary for Myc induced proliferation[15] or cell growth.[16]

There have been several studies that have clearly indicated Myc's role in cell competition.[17]

A major effect of c-myc is B cell proliferation, and gain of MYC has been associated with B cell malignancies and their increased aggressiveness, including histological transformation.[18] In B cells, Myc acts as a classical oncogene by regulating a number of pro-proliferative and anti-apoptotic pathways, this also includes tuning of BCR signaling and CD40 signaling in regulation of microRNAs (miR-29, miR-150, miR-17-92).[19]

c-Myc induces MTDH(AEG-1) gene expression and in turn itself requires AEG-1 oncogene for its expression.

Myc-nick

[edit]

Myc-nick is a cytoplasmic form of Myc produced by a partial proteolytic cleavage of full-length c-Myc and N-Myc.[20] Myc cleavage is mediated by the calpain family of calcium-dependent cytosolic proteases.

The cleavage of Myc by calpains is a constitutive process but is enhanced under conditions that require rapid downregulation of Myc levels, such as during terminal differentiation. Upon cleavage, the C-terminus of Myc (containing the DNA binding domain) is degraded, while Myc-nick, the N-terminal segment 298-residue segment remains in the cytoplasm. Myc-nick contains binding domains for histone acetyltransferases and for ubiquitin ligases.

The functions of Myc-nick are currently under investigation, but this new Myc family member was found to regulate cell morphology, at least in part, by interacting with acetyl transferases to promote the acetylation of α-tubulin. Ectopic expression of Myc-nick accelerates the differentiation of committed myoblasts into muscle cells.

Clinical significance

[edit]A large body of evidence shows that Myc genes and proteins are highly relevant for treating tumors.[9] Except for early response genes, Myc universally upregulates gene expression. Furthermore, the upregulation is nonlinear. Genes for which expression is already significantly upregulated in the absence of Myc are strongly boosted in the presence of Myc, whereas genes for which expression is low in the absence Myc get only a small boost when Myc is present.[6]

Inactivation of SUMO-activating enzyme (SAE1 / SAE2) in the presence of Myc hyperactivation results in mitotic catastrophe and cell death in cancer cells. Hence inhibitors of SUMOylation may be a possible treatment for cancer.[21]

Amplification of the MYC gene was found in a significant number of epithelial ovarian cancer cases.[22] In TCGA datasets, the amplification of Myc occurs in several cancer types, including breast, colorectal, pancreatic, gastric, and uterine cancers.[23]

In the experimental transformation process of normal cells into cancer cells, the MYC gene can cooperate with the RAS gene.[24][25]

Expression of Myc is highly dependent on BRD4 function in some cancers.[26][27] BET inhibitors have been used to successfully block Myc function in pre-clinical cancer models and are currently being evaluated in clinical trials.[28]

MYC expression is controlled by a wide variety of noncoding RNAs, including miRNA, lncRNA, and circRNA. Some of these RNAs have been shown to be specific for certain types of human tissues and tumors.[29] Changes in the expression of such RNAs can potentially be used to develop targeted tumor therapy.

MYC rearrangements

[edit]MYC chromosomal rearrangements (MYC-R) occur in 10% to 15% of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCLs), an aggressive Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL). Patients with MYC-R have inferior outcomes and can be classified as single-hit, when they only have MYC-R; as double hit when the rearrangement is accompanied by a translocation of BCL2 or BCL6; and as triple hit when MYC-R includes both BCL2 and BCL6. Double and triple hit lymphoma have been recently classified as high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBCL) and it is associated with a poor prognosis.[30]

MYC-R in DLBCL/HGBCL is believed to arise through the aberrant activity of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AICDA), which facilitates somatic hypermutation (SHM) and class-switch recombination (CSR).[31] Although AICDA primarily targets IG loci for SHM and CSR, its off-target mutagenic effects can impact lymphoma-associated oncogenes like MYC, potentially leading to oncogenic rearrangements. The breakpoints in MYC rearrangements show considerable variability within the MYC region. These breakpoints may occur within the so-called “genic cluster,” a region spanning approximately 1.5 kb upstream of the transcription start site, as well as the first exon and intron of MYC.[32]

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has become a routine practice in many clinical laboratories for lymphoma characterization. A break-apart (BAP) FISH probe is commonly utilized for the detection of MYC-R due to the variability of breakpoints in the MYC locus and the diversity of rearrangement partners, including immunoglobulin (IG) and non-IG partners (i.e. BCL2/BCL6). The MYC BAP probe includes a red and a green probe which hybridize 5’ and 3’ to the MYC gen, respectively. In an intact MYC locus, these probes yield a fusion signal. When MYC-R occur, two types of signals can be observed:

- Balanced patterns: These patterns present separate red and green signals.

- Unbalanced patterns: When isolated red or green signals in the absence of the corresponding green or red signal is observed. Unbalanced MYC-R are frequently associated with increased MYC expression.

There is a large variability in the interpretation of unbalanced MYC BAP results among the scientists, which can impact diagnostic classification and therapeutic management of the patients.[33][34]

Animal models

[edit]In Drosophila Myc is encoded by the diminutive locus, (which was known to geneticists prior to 1935).[35] Classical diminutive alleles resulted in a viable animal with small body size. Drosophila has subsequently been used to implicate Myc in cell competition,[36] endoreplication,[37] and cell growth.[38]

During the discovery of Myc gene, it was realized that chromosomes that reciprocally translocate to chromosome 8 contained immunoglobulin genes at the break-point. To study the mechanism of tumorigenesis in Burkitt lymphoma by mimicking expression pattern of Myc in these cancer cells, transgenic mouse models were developed. Myc gene placed under the control of IgM heavy chain enhancer in transgenic mice gives rise to mainly lymphomas. Later on, in order to study effects of Myc in other types of cancer, transgenic mice that overexpress Myc in different tissues (liver, breast) were also made. In all these mouse models overexpression of Myc causes tumorigenesis, illustrating the potency of Myc oncogene. In a study with mice, reduced expression of Myc was shown to induce longevity, with significantly extended median and maximum lifespans in both sexes and a reduced mortality rate across all ages, better health, cancer progression was slower, better metabolism and they had smaller bodies. Also, Less TOR, AKT, S6K and other changes in energy and metabolic pathways (such as AMPK, more oxygen consumption, more body movements, etc.). The study by John M. Sedivy and others used Cre-Loxp -recombinase to knockout one copy of Myc and this resulted in a "Haplo-insufficient" genotype noted as Myc+/-. The phenotypes seen oppose the effects of normal aging and are shared with many other long-lived mouse models such as CR (calorie restriction) ames dwarf, rapamycin, metformin and resveratrol. One study found that Myc and p53 genes were key to the survival of chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) cells. Targeting Myc and p53 proteins with drugs gave positive results on mice with CML.[39][40]

Relationship to stem cells

[edit]Myc genes play a number of normal roles in stem cells including pluripotent stem cells. In neural stem cells, N-Myc promotes a rapidly proliferative stem cell and precursor-like state in the developing brain, while inhibiting differentiation.[41] In hematopoietic stem cells, Myc controls the balance between self-renewal and differentiation.[42] In particular, long-term hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) express low levels of c-Myc, ensuring self-renewal. Enforced expression of c-Myc in LT-HSCs promotes differentiation at the expense of self-renewal, resulting in stem cell exhaustion.[42] In pathological states and specifically in acute myeloid leukemia, oxidant stress can trigger higher levels of Myc expression that affects the behavior of leukemia stem cells.[43]

c-Myc plays a major role in the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). It is one of the original factors discovered by Yamanaka et al. to encourage cells to return to a 'stem-like' state alongside transcription factors Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4. It has since been shown that it is possible to generate iPSCs without c-Myc.[44]

Interactions

[edit]Myc has been shown to interact with:

- ACTL6A[45]

- BRCA1[46][47][48][49]

- Bcl-2[50]

- Cyclin T1[51]

- CHD8[52]

- DNMT3A[53]

- EP400[54]

- GTF2I[55]

- HTATIP[56]

- let-7[57][58][59]

- MAPK1[50][60][61]

- MAPK8[62]

- MAX[63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75]

- MLH1[67]

- MYCBP2[76]

- MYCBP[77]

- NMI[46]

- NFYB[78]

- NFYC[79]

- P73[80]

- PCAF[81]

- PFDN5[82][83]

- RuvB-like 1[45][54]

- SAP130[81]

- SMAD2[84]

- SMAD3[84]

- SMARCA4[45][63]

- SMARCB1[66]

- SUPT3H[81]

- TIAM1[85]

- TADA2L[81]

- TAF9[81]

- TFAP2A[86]

- TRRAP[45][64][65][81]

- WDR5[87]

- YY1[88] and

- ZBTB17.[89][90]

- C2orf16[91]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Myc". NCBI.

- ^ Finver SN, Nishikura K, Finger LR, Haluska FG, Finan J, Nowell PC, Croce CM (May 1988). "Sequence analysis of the Myc oncogene involved in the t(8;14)(q24;q11) chromosome translocation in a human leukemia T-cell line indicates that putative regulatory regions are not altered". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 85 (9): 3052–6. Bibcode:1988PNAS...85.3052F. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.9.3052. PMC 280141. PMID 2834731.

- ^ Begley S (2013-01-09). "DNA pioneer James Watson takes aim at cancer establishments". Reuters.

- ^ Carabet LA, Rennie PS, Cherkasov A (December 2018). "Therapeutic Inhibition of Myc in Cancer. Structural Bases and Computer-Aided Drug Discovery Approaches". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20 (1): 120. doi:10.3390/ijms20010120. PMC 6337544. PMID 30597997.

- ^ Dang CV, Reddy EP, Shokat KM, Soucek L (August 2017). "Drugging the 'undruggable' cancer targets". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 17 (8): 502–508. doi:10.1038/nrc.2017.36. PMC 5945194. PMID 28643779.

- ^ a b Nie Z, Hu G, Wei G, Cui K, Yamane A, Resch W, Wang R, Green DR, Tessarollo L, Casellas R, Zhao K, Levens D (September 2012). "c-Myc is a universal amplifier of expressed genes in lymphocytes and embryonic stem cells". Cell. 151 (1): 68–79. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.033. PMC 3471363. PMID 23021216.

- ^ Gearhart J, Pashos EE, Prasad MK (October 2007). "Pluripotency redux--advances in stem-cell research". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (15): 1469–72. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078126. PMID 17928593.

- ^ Cotterman R, Jin VX, Krig SR, Lemen JM, Wey A, Farnham PJ, Knoepfler PS (December 2008). "N-Myc regulates a widespread euchromatic program in the human genome partially independent of its role as a classical transcription factor". Cancer Research. 68 (23): 9654–62. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1961. PMC 2637654. PMID 19047142.

- ^ a b Wolf E, Eilers M (2020). "Targeting MYC Proteins for Tumor Therapy". Annual Review of Cancer Biology. 4: 61–75. doi:10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030518-055826.

- ^ Rahl PB, Young RA (January 2014). "MYC and transcription elongation". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 4 (1): a020990. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a020990. PMC 3869279. PMID 24384817.

- ^ Dominguez-Sola D, Ying CY, Grandori C, Ruggiero L, Chen B, Li M, Galloway DA, Gu W, Gautier J, Dalla-Favera R (July 2007). "Non-transcriptional control of DNA replication by c-Myc". Nature. 448 (7152): 445–51. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..445D. doi:10.1038/nature05953. PMID 17597761. S2CID 4422771.

- ^ Denis N, Kitzis A, Kruh J, Dautry F, Corcos D (August 1991). "Stimulation of methotrexate resistance and dihydrofolate reductase gene amplification by c-myc". Oncogene. 6 (8): 1453–7. PMID 1886715.

- ^ Campisi J, Gray HE, Pardee AB, Dean M, Sonenshein GE (1984). "Cell-cycle control of c-myc but not c-ras expression is lost following chemical transformation". Cell. 36 (2): 241–7. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90217-4. PMID 6692471. S2CID 29661004.

- ^ Liu YC, Li F, Handler J, Huang CR, Xiang Y, Neretti N, Sedivy JM, Zeller KI, Dang CV (July 2008). "Global regulation of nucleotide biosynthetic genes by c-Myc". PLOS ONE. 3 (7): e2722. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2722L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002722. PMC 2444028. PMID 18628958.

- ^ Mannava S, Grachtchouk V, Wheeler LJ, Im M, Zhuang D, Slavina EG, Mathews CK, Shewach DS, Nikiforov MA (August 2008). "Direct role of nucleotide metabolism in C-MYC-dependent proliferation of melanoma cells". Cell Cycle. 7 (15): 2392–400. doi:10.4161/cc.6390. PMC 3744895. PMID 18677108.

- ^ Aughey GN, Grice SJ, Liu JL (February 2016). "The Interplay between Myc and CTP Synthase in Drosophila". PLOS Genetics. 12 (2): e1005867. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005867. PMC 4759343. PMID 26889675.

- ^ Clavería C, Giovinazzo G, Sierra R, Torres M (August 2013). "Myc-driven endogenous cell competition in the early mammalian embryo". Nature. 500 (7460): 39–44. Bibcode:2013Natur.500...39C. doi:10.1038/nature12389. PMID 23842495. S2CID 4414411.

- ^ de Alboran IM, O'Hagan RC, Gärtner F, Malynn B, Davidson L, Rickert R, Rajewsky K, DePinho RA, Alt FW (January 2001). "Analysis of C-MYC function in normal cells via conditional gene-targeted mutation". Immunity. 14 (1): 45–55. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00088-7. PMID 11163229.

- ^ Mendell JT (April 2008). "miRiad roles for the miR-17-92 cluster in development and disease". Cell. 133 (2): 217–22. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.001. PMC 2732113. PMID 18423194.

- ^ Conacci-Sorrell M, Ngouenet C, Eisenman RN (August 2010). "Myc-nick: a cytoplasmic cleavage product of Myc that promotes alpha-tubulin acetylation and cell differentiation". Cell. 142 (3): 480–93. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.037. PMC 2923036. PMID 20691906.

- ^ Kessler JD, Kahle KT, Sun T, Meerbrey KL, Schlabach MR, Schmitt EM, Skinner SO, Xu Q, Li MZ, Hartman ZC, Rao M, Yu P, Dominguez-Vidana R, Liang AC, Solimini NL, Bernardi RJ, Yu B, Hsu T, Golding I, Luo J, Osborne CK, Creighton CJ, Hilsenbeck SG, Schiff R, Shaw CA, Elledge SJ, Westbrook TF (January 2012). "A SUMOylation-dependent transcriptional subprogram is required for Myc-driven tumorigenesis". Science. 335 (6066): 348–53. Bibcode:2012Sci...335..348K. doi:10.1126/science.1212728. PMC 4059214. PMID 22157079.

- ^ Ross JS, Ali SM, Wang K, Palmer G, Yelensky R, Lipson D, Miller VA, Zajchowski D, Shawver LK, Stephens PJ (September 2013). "Comprehensive genomic profiling of epithelial ovarian cancer by next generation sequencing-based diagnostic assay reveals new routes to targeted therapies". Gynecologic Oncology. 130 (3): 554–9. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.06.019. PMID 23791828.

- ^ Chen Y, McGee J, Chen X, Doman TN, Gong X, Zhang Y, Hamm N, Ma X, Higgs RE, Bhagwat SV, Buchanan S, Peng SB, Staschke KA, Yadav V, Yue Y, Kouros-Mehr H (2014). "Identification of druggable cancer driver genes amplified across TCGA datasets". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e98293. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...998293C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098293. PMC 4038530. PMID 24874471.

- ^ Land H, Parada LF, Weinberg RA (1983). "Tumorigenic conversion of primary embryo fibroblasts requires at least two cooperating oncogenes". Nature. 304 (5927): 596–602. Bibcode:1983Natur.304..596L. doi:10.1038/304596a0. PMID 6308472. S2CID 2338865.

- ^ Radner H, el-Shabrawi Y, Eibl RH, Brüstle O, Kenner L, Kleihues P, Wiestler OD (1993). "Tumor induction by ras and myc oncogenes in fetal and neonatal brain: modulating effects of developmental stage and retroviral dose". Acta Neuropathologica. 86 (5): 456–65. doi:10.1007/bf00228580. PMID 8310796. S2CID 2972931.

- ^ Fowler T, Ghatak P, Price DH, Conaway R, Conaway J, Chiang CM, Bradner JE, Shilatifard A, Roy AL (2014). "Regulation of MYC expression and differential JQ1 sensitivity in cancer cells". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e87003. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...987003F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087003. PMC 3900694. PMID 24466310.

- ^ Shi J, Vakoc CR (June 2014). "The mechanisms behind the therapeutic activity of BET bromodomain inhibition". Molecular Cell. 54 (5): 728–36. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.016. PMC 4236231. PMID 24905006.

- ^ Delmore JE, Issa GC, Lemieux ME, Rahl PB, Shi J, Jacobs HM, Kastritis E, Gilpatrick T, Paranal RM, Qi J, Chesi M, Schinzel AC, McKeown MR, Heffernan TP, Vakoc CR, Bergsagel PL, Ghobrial IM, Richardson PG, Young RA, Hahn WC, Anderson KC, Kung AL, Bradner JE, Mitsiades CS (September 2011). "BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc". Cell. 146 (6): 904–17. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. PMC 3187920. PMID 21889194.

- ^ Stasevich EM, Murashko MM, Zinevich LS, Demin DE, Schwartz AM (July 2021). "The Role of Non-Coding RNAs in the Regulation of the Proto-Oncogene MYC in Different Types of Cancer". Biomedicines. 9 (8): 921. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9080921. PMC 8389562. PMID 34440124.

- ^ Eertink JJ, Zwezerijnen GJ, Wiegers SE, Pieplenbosch S, Chamuleau ME, Lugtenburg PJ, de Jong D, Ylstra B, Mendeville M, Dührsen U, Hanoun C, Hüttmann A, Richter J, Klapper W, Jauw YW, Hoekstra OS, de Vet HC, Boellaard R, Zijlstra JM (24 January 2023). "Baseline radiomics features and MYC rearrangement status predict progression in aggressive B-cell lymphoma". Blood Advances. 7 (2): 214–223. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008629. PMC 9841040. PMID 36306337.

- ^ Lieber MR (June 2016). "Mechanisms of human lymphoid chromosomal translocations". Nature Reviews Cancer. 16 (6): 387–398. doi:10.1038/nrc.2016.40. PMC 5336345. PMID 27220482.

- ^ Chong LC, Ben-Neriah S, Slack GW, Freeman C, Ennishi D, Mottok A, Collinge B, Abrisqueta P, Farinha P, Boyle M, Meissner B, Kridel R, Gerrie AS, Villa D, Savage KJ, Sehn LH, Siebert R, Morin RD, Gascoyne RD, Marra MA, Connors JM, Mungall AJ, Steidl C, Scott DW (22 October 2018). "High-resolution architecture and partner genes of MYC rearrangements in lymphoma with DLBCL morphology". Blood Advances. 2 (20): 2755–2765. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018023572. PMC 6199666. PMID 30348671.

- ^ Rosenwald A, Bens S, Advani R, Barrans S, Copie-Bergman C, Elsensohn MH, Natkunam Y, Calaminici M, Sander B, Baia M, Smith A, Painter D, Pham L, Zhao S, Ziepert M, Jordanova ES, Molina TJ, Kersten MJ, Kimby E, Klapper W, Raemaekers J, Schmitz N, Jardin F, Stevens WB, Hoster E, Hagenbeek A, Gribben JG, Siebert R, Gascoyne RD, Scott DW, Gaulard P, Salles G, Burton C, de Jong D, Sehn LH, Maucort-Boulch D (10 December 2019). "Prognostic Significance of MYC Rearrangement and Translocation Partner in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Study by the Lunenburg Lymphoma Biomarker Consortium". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 37 (35): 3359–3368. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00743. PMID 31498031.

- ^ Gagnon MF, Penheiter AR, Harris F, Sadeghian D, Johnson SH, Karagouga G, McCune A, Zepeda-Mendoza C, Greipp PT, Xu X, Ketterling RP, McPhail ED, King RL, Peterson JF, Vasmatzis G, Baughn LB (19 December 2023). "Unraveling the genomic underpinnings of unbalanced MYC break-apart FISH results using whole genome sequencing analysis". Blood Cancer Journal. 13 (1): 190. doi:10.1038/s41408-023-00967-8. PMC 10730864. PMID 38114462.

- ^ Slizynska H (May 1938). "Salivary Chromosome Analysis of the White-Facet Region of Drosophila Melanogaster". Genetics. 23 (3): 291–9. doi:10.1093/genetics/23.3.291. PMC 1209013. PMID 17246888.

- ^ de la Cova C, Abril M, Bellosta P, Gallant P, Johnston LA (April 2004). "Drosophila myc regulates organ size by inducing cell competition". Cell. 117 (1): 107–16. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00214-4. PMID 15066286. S2CID 18357397.

- ^ Maines JZ, Stevens LM, Tong X, Stein D (February 2004). "Drosophila dMyc is required for ovary cell growth and endoreplication". Development. 131 (4): 775–86. doi:10.1242/dev.00932. PMID 14724122. S2CID 721144.

- ^ Johnston LA, Prober DA, Edgar BA, Eisenman RN, Gallant P (September 1999). "Drosophila myc regulates cellular growth during development" (PDF). Cell. 98 (6): 779–90. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81512-3. PMC 10176494. PMID 10499795. S2CID 5215149. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-04-03. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- ^ Abraham SA, Hopcroft LE, Carrick E, Drotar ME, Dunn K, Williamson AJ, et al. (June 2016). "Dual targeting of p53 and c-MYC selectively eliminates leukaemic stem cells". Nature. 534 (7607): 341–6. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..341A. doi:10.1038/nature18288. PMC 4913876. PMID 27281222.

- ^ "Scientists identify drugs to target 'Achilles heel' of Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia cells". myScience. 2016-06-08. Archived from the original on 2018-07-27. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ Knoepfler PS, Cheng PF, Eisenman RN (October 2002). "N-myc is essential during neurogenesis for the rapid expansion of progenitor cell populations and the inhibition of neuronal differentiation". Genes & Development. 16 (20): 2699–712. doi:10.1101/gad.1021202. PMC 187459. PMID 12381668.

- ^ a b Wilson A, Murphy MJ, Oskarsson T, Kaloulis K, Bettess MD, Oser GM, et al. (November 2004). "c-Myc controls the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation". Genes & Development. 18 (22): 2747–63. doi:10.1101/gad.313104. PMC 528895. PMID 15545632.

- ^ Vlahopoulos S, Pan L, Varisli L, Dancik GM, Karantanos T, Boldogh I (Dec 2023). "OGG1 as an Epigenetic Reader Affects NFκB: What This Means for Cancer". Cancers. 16 (1): 148. doi:10.3390/cancers16010148. PMC 10778025. PMID 38201575.

- ^ Takahashi K, Yamanaka S (March 2016). "A decade of transcription factor-mediated reprogramming to pluripotency". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 17 (3): 183–93. doi:10.1038/nrm.2016.8. PMID 26883003. S2CID 7593915.

- ^ a b c d Park J, Wood MA, Cole MD (March 2002). "BAF53 forms distinct nuclear complexes and functions as a critical c-Myc-interacting nuclear cofactor for oncogenic transformation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 22 (5): 1307–16. doi:10.1128/mcb.22.5.1307-1316.2002. PMC 134713. PMID 11839798.

- ^ a b Li H, Lee TH, Avraham H (June 2002). "A novel tricomplex of BRCA1, Nmi, and c-Myc inhibits c-Myc-induced human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene (hTERT) promoter activity in breast cancer". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (23): 20965–73. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112231200. PMID 11916966.

- ^ Xiong J, Fan S, Meng Q, Schramm L, Wang C, Bouzahza B, Zhou J, Zafonte B, Goldberg ID, Haddad BR, Pestell RG, Rosen EM (December 2003). "BRCA1 inhibition of telomerase activity in cultured cells". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (23): 8668–90. doi:10.1128/mcb.23.23.8668-8690.2003. PMC 262673. PMID 14612409.

- ^ Zhou C, Liu J (March 2003). "Inhibition of human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene expression by BRCA1 in human ovarian cancer cells". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 303 (1): 130–6. doi:10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00318-8. PMID 12646176.

- ^ Wang Q, Zhang H, Kajino K, Greene MI (October 1998). "BRCA1 binds c-Myc and inhibits its transcriptional and transforming activity in cells". Oncogene. 17 (15): 1939–48. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202403. PMID 9788437. S2CID 30771256.

- ^ a b Jin Z, Gao F, Flagg T, Deng X (September 2004). "Tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone promotes functional cooperation of Bcl2 and c-Myc through phosphorylation in regulating cell survival and proliferation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (38): 40209–19. doi:10.1074/jbc.M404056200. PMID 15210690.

- ^ Kanazawa S, Soucek L, Evan G, Okamoto T, Peterlin BM (August 2003). "c-Myc recruits P-TEFb for transcription, cellular proliferation and apoptosis". Oncogene. 22 (36): 5707–11. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206800. PMID 12944920. S2CID 29519364.

- ^ Dingar D, Kalkat M, Chan PK, Srikumar T, Bailey SD, Tu WB, Coyaud E, Ponzielli R, Kolyar M, Jurisica I, Huang A, Lupien M, Penn LZ, Raught B (April 2015). "BioID identifies novel c-MYC interacting partners in cultured cells and xenograft tumors". Journal of Proteomics. 118 (12): 95–111. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2014.09.029. PMID 25452129.

- ^ Brenner C, Deplus R, Didelot C, Loriot A, Viré E, De Smet C, Gutierrez A, Danovi D, Bernard D, Boon T, Pelicci PG, Amati B, Kouzarides T, de Launoit Y, Di Croce L, Fuks F (January 2005). "Myc represses transcription through recruitment of DNA methyltransferase corepressor". The EMBO Journal. 24 (2): 336–46. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600509. PMC 545804. PMID 15616584.

- ^ a b Fuchs M, Gerber J, Drapkin R, Sif S, Ikura T, Ogryzko V, Lane WS, Nakatani Y, Livingston DM (August 2001). "The p400 complex is an essential E1A transformation target". Cell. 106 (3): 297–307. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00450-0. PMID 11509179. S2CID 15634637.

- ^ Roy AL, Carruthers C, Gutjahr T, Roeder RG (September 1993). "Direct role for Myc in transcription initiation mediated by interactions with TFII-I". Nature. 365 (6444): 359–61. Bibcode:1993Natur.365..359R. doi:10.1038/365359a0. PMID 8377829. S2CID 4354157.

- ^ Frank SR, Parisi T, Taubert S, Fernandez P, Fuchs M, Chan HM, Livingston DM, Amati B (June 2003). "MYC recruits the TIP60 histone acetyltransferase complex to chromatin". EMBO Reports. 4 (6): 575–80. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.embor861. PMC 1319201. PMID 12776177.

- ^ Chang TC, Yu D, Lee YS, Wentzel EA, Arking DE, West KM, Dang CV, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Mendell JT (January 2008). "Widespread microRNA repression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis". Nature Genetics. 40 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.30. PMC 2628762. PMID 18066065.

- ^ Koscianska E, Baev V, Skreka K, Oikonomaki K, Rusinov V, Tabler M, Kalantidis K (2007). "Prediction and preliminary validation of oncogene regulation by miRNAs". BMC Molecular Biology. 8: 79. doi:10.1186/1471-2199-8-79. PMC 2096627. PMID 17877811.

- ^ Ioannidis P, Mahaira LG, Perez SA, Gritzapis AD, Sotiropoulou PA, Kavalakis GJ, Antsaklis AI, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M (May 2005). "CRD-BP/IMP1 expression characterizes cord blood CD34+ stem cells and affects c-myc and IGF-II expression in MCF-7 cancer cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (20): 20086–93. doi:10.1074/jbc.M410036200. PMID 15769738.

- ^ Gupta S, Davis RJ (October 1994). "MAP kinase binds to the NH2-terminal activation domain of c-Myc". FEBS Letters. 353 (3): 281–5. Bibcode:1994FEBSL.353..281G. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)01052-8. PMID 7957875. S2CID 45404088.

- ^ Tournier C, Whitmarsh AJ, Cavanagh J, Barrett T, Davis RJ (July 1997). "Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 is an activator of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (14): 7337–42. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.7337T. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.14.7337. PMC 23822. PMID 9207092.

- ^ Noguchi K, Kitanaka C, Yamana H, Kokubu A, Mochizuki T, Kuchino Y (November 1999). "Regulation of c-Myc through phosphorylation at Ser-62 and Ser-71 by c-Jun N-terminal kinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (46): 32580–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.46.32580. PMID 10551811.

- ^ a b Ewing RM, Chu P, Elisma F, Li H, Taylor P, Climie S, McBroom-Cerajewski L, Robinson MD, O'Connor L, Li M, Taylor R, Dharsee M, Ho Y, Heilbut A, Moore L, Zhang S, Ornatsky O, Bukhman YV, Ethier M, Sheng Y, Vasilescu J, Abu-Farha M, Lambert JP, Duewel HS, Stewart II, Kuehl B, Hogue K, Colwill K, Gladwish K, Muskat B, Kinach R, Adams SL, Moran MF, Morin GB, Topaloglou T, Figeys D (2007). "Large-scale mapping of human protein-protein interactions by mass spectrometry". Molecular Systems Biology. 3: 89. doi:10.1038/msb4100134. PMC 1847948. PMID 17353931.

- ^ a b McMahon SB, Wood MA, Cole MD (January 2000). "The essential cofactor TRRAP recruits the histone acetyltransferase hGCN5 to c-Myc". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 20 (2): 556–62. doi:10.1128/mcb.20.2.556-562.2000. PMC 85131. PMID 10611234.

- ^ a b McMahon SB, Van Buskirk HA, Dugan KA, Copeland TD, Cole MD (August 1998). "The novel ATM-related protein TRRAP is an essential cofactor for the c-Myc and E2F oncoproteins". Cell. 94 (3): 363–74. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81479-8. PMID 9708738. S2CID 17693834.

- ^ a b Cheng SW, Davies KP, Yung E, Beltran RJ, Yu J, Kalpana GV (May 1999). "c-MYC interacts with INI1/hSNF5 and requires the SWI/SNF complex for transactivation function". Nature Genetics. 22 (1): 102–5. doi:10.1038/8811. PMID 10319872. S2CID 12945791.

- ^ a b Mac Partlin M, Homer E, Robinson H, McCormick CJ, Crouch DH, Durant ST, Matheson EC, Hall AG, Gillespie DA, Brown R (February 2003). "Interactions of the DNA mismatch repair proteins MLH1 and MSH2 with c-MYC and MAX". Oncogene. 22 (6): 819–25. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206252. PMID 12584560.

- ^ Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN (March 1991). "Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc". Science. 251 (4998): 1211–7. Bibcode:1991Sci...251.1211B. doi:10.1126/science.2006410. PMID 2006410.

- ^ Lee CM, Onésime D, Reddy CD, Dhanasekaran N, Reddy EP (October 2002). "JLP: A scaffolding protein that tethers JNK/p38MAPK signaling modules and transcription factors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (22): 14189–94. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9914189L. doi:10.1073/pnas.232310199. PMC 137859. PMID 12391307.

- ^ Billin AN, Eilers AL, Queva C, Ayer DE (December 1999). "Mlx, a novel Max-like BHLHZip protein that interacts with the Max network of transcription factors". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (51): 36344–50. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.51.36344. PMID 10593926.

- ^ Gupta K, Anand G, Yin X, Grove L, Prochownik EV (March 1998). "Mmip1: a novel leucine zipper protein that reverses the suppressive effects of Mad family members on c-myc". Oncogene. 16 (9): 1149–59. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201634. PMID 9528857. S2CID 30576019.

- ^ Meroni G, Reymond A, Alcalay M, Borsani G, Tanigami A, Tonlorenzi R, Lo Nigro C, Messali S, Zollo M, Ledbetter DH, Brent R, Ballabio A, Carrozzo R (May 1997). "Rox, a novel bHLHZip protein expressed in quiescent cells that heterodimerizes with Max, binds a non-canonical E box and acts as a transcriptional repressor". The EMBO Journal. 16 (10): 2892–906. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.10.2892. PMC 1169897. PMID 9184233.

- ^ Nair SK, Burley SK (January 2003). "X-ray structures of Myc-Max and Mad-Max recognizing DNA. Molecular bases of regulation by proto-oncogenic transcription factors". Cell. 112 (2): 193–205. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01284-9. PMID 12553908. S2CID 16142388.

- ^ FitzGerald MJ, Arsura M, Bellas RE, Yang W, Wu M, Chin L, Mann KK, DePinho RA, Sonenshein GE (April 1999). "Differential effects of the widely expressed dMax splice variant of Max on E-box vs initiator element-mediated regulation by c-Myc". Oncogene. 18 (15): 2489–98. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202611. PMID 10229200.

- ^ Meroni G, Cairo S, Merla G, Messali S, Brent R, Ballabio A, Reymond A (July 2000). "Mlx, a new Max-like bHLHZip family member: the center stage of a novel transcription factors regulatory pathway?". Oncogene. 19 (29): 3266–77. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203634. PMID 10918583. S2CID 17891130.

- ^ Guo Q, Xie J, Dang CV, Liu ET, Bishop JM (August 1998). "Identification of a large Myc-binding protein that contains RCC1-like repeats". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (16): 9172–7. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9172G. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.16.9172. PMC 21311. PMID 9689053.

- ^ Taira T, Maëda J, Onishi T, Kitaura H, Yoshida S, Kato H, Ikeda M, Tamai K, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Ariga H (August 1998). "AMY-1, a novel C-MYC binding protein that stimulates transcription activity of C-MYC". Genes to Cells. 3 (8): 549–65. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00206.x. PMID 9797456. S2CID 41886122.

- ^ Izumi H, Molander C, Penn LZ, Ishisaki A, Kohno K, Funa K (April 2001). "Mechanism for the transcriptional repression by c-Myc on PDGF beta-receptor". Journal of Cell Science. 114 (Pt 8): 1533–44. doi:10.1242/jcs.114.8.1533. PMID 11282029.

- ^ Taira T, Sawai M, Ikeda M, Tamai K, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Ariga H (August 1999). "Cell cycle-dependent switch of up-and down-regulation of human hsp70 gene expression by interaction between c-Myc and CBF/NF-Y". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (34): 24270–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.34.24270. PMID 10446203.

- ^ Uramoto H, Izumi H, Ise T, Tada M, Uchiumi T, Kuwano M, Yasumoto K, Funa K, Kohno K (August 2002). "p73 Interacts with c-Myc to regulate Y-box-binding protein-1 expression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (35): 31694–702. doi:10.1074/jbc.M200266200. PMID 12080043.

- ^ a b c d e f Liu X, Tesfai J, Evrard YA, Dent SY, Martinez E (May 2003). "c-Myc transformation domain recruits the human STAGA complex and requires TRRAP and GCN5 acetylase activity for transcription activation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (22): 20405–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M211795200. PMC 4031917. PMID 12660246.

- ^ Mori K, Maeda Y, Kitaura H, Taira T, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Ariga H (November 1998). "MM-1, a novel c-Myc-associating protein that represses transcriptional activity of c-Myc". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (45): 29794–800. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.45.29794. PMID 9792694.

- ^ Fujioka Y, Taira T, Maeda Y, Tanaka S, Nishihara H, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Nagashima K, Ariga H (November 2001). "MM-1, a c-Myc-binding protein, is a candidate for a tumor suppressor in leukemia/lymphoma and tongue cancer". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (48): 45137–44. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106127200. PMID 11567024.

- ^ a b Feng XH, Liang YY, Liang M, Zhai W, Lin X (January 2002). "Direct interaction of c-Myc with Smad2 and Smad3 to inhibit TGF-beta-mediated induction of the CDK inhibitor p15(Ink4B)". Molecular Cell. 9 (1): 133–43. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00430-0. PMID 11804592.

- ^ Otsuki Y, Tanaka M, Kamo T, Kitanaka C, Kuchino Y, Sugimura H (February 2003). "Guanine nucleotide exchange factor, Tiam1, directly binds to c-Myc and interferes with c-Myc-mediated apoptosis in rat-1 fibroblasts". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (7): 5132–40. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206733200. PMID 12446731.

- ^ Gaubatz S, Imhof A, Dosch R, Werner O, Mitchell P, Buettner R, Eilers M (April 1995). "Transcriptional activation by Myc is under negative control by the transcription factor AP-2". The EMBO Journal. 14 (7): 1508–19. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07137.x. PMC 398238. PMID 7729426.

- ^ Thomas LR, Wang Q, Grieb BC, Phan J, Foshage AM, Sun Q, Olejniczak ET, Clark T, Dey S, Lorey S, Alicie B, Howard GC, Cawthon B, Ess KC, Eischen CM, Zhao Z, Fesik SW, Tansey WP (May 2015). "Interaction with WDR5 promotes target gene recognition and tumorigenesis by MYC". Molecular Cell. 58 (3): 440–52. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.028. PMC 4427524. PMID 25818646.

- ^ Shrivastava A, Saleque S, Kalpana GV, Artandi S, Goff SP, Calame K (December 1993). "Inhibition of transcriptional regulator Yin-Yang-1 by association with c-Myc". Science. 262 (5141): 1889–92. Bibcode:1993Sci...262.1889S. doi:10.1126/science.8266081. PMID 8266081.

- ^ Staller P, Peukert K, Kiermaier A, Seoane J, Lukas J, Karsunky H, Möröy T, Bartek J, Massagué J, Hänel F, Eilers M (April 2001). "Repression of p15INK4b expression by Myc through association with Miz-1". Nature Cell Biology. 3 (4): 392–9. doi:10.1038/35070076. PMID 11283613. S2CID 12696178.

- ^ Peukert K, Staller P, Schneider A, Carmichael G, Hänel F, Eilers M (September 1997). "An alternative pathway for gene regulation by Myc". The EMBO Journal. 16 (18): 5672–86. doi:10.1093/emboj/16.18.5672. PMC 1170199. PMID 9312026.

- ^ "PSICQUIC View". ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 2019-05-02.

Further reading

[edit]- Ruf IK, Rhyne PW, Yang H, Borza CM, Hutt-Fletcher LM, Cleveland JL, Sample JT (2001). "EBV Regulates c-MYC, Apoptosis, and Tumorigenicity in Burkitt's Lymphoma". Epstein-Barr Virus and Human Cancer. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 258. pp. 153–60. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-56515-1_10. ISBN 978-3-642-62568-8. PMID 11443860.

- Lüscher B (October 2001). "Function and regulation of the transcription factors of the Myc/Max/Mad network". Gene. 277 (1–2): 1–14. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00697-7. PMID 11602341.

- Hoffman B, Amanullah A, Shafarenko M, Liebermann DA (May 2002). "The proto-oncogene c-myc in hematopoietic development and leukemogenesis". Oncogene. 21 (21): 3414–21. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205400. PMID 12032779. S2CID 8720539.

- Pelengaris S, Khan M, Evan G (October 2002). "c-MYC: more than just a matter of life and death". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2 (10): 764–76. doi:10.1038/nrc904. PMID 12360279. S2CID 13226062.

- Nilsson JA, Cleveland JL (December 2003). "Myc pathways provoking cell suicide and cancer". Oncogene. 22 (56): 9007–21. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207261. PMID 14663479. S2CID 24758874.

- Dang CV, O'donnell KA, Juopperi T (September 2005). "The great MYC escape in tumorigenesis". Cancer Cell. 8 (3): 177–8. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.005. PMID 16169462.

- Dang CV, Li F, Lee LA (November 2005). "Could MYC induction of mitochondrial biogenesis be linked to ROS production and genomic instability?". Cell Cycle. 4 (11): 1465–6. doi:10.4161/cc.4.11.2121. PMID 16205115.

- Coller HA, Forman JJ, Legesse-Miller A (August 2007). ""Myc'ed messages": myc induces transcription of E2F1 while inhibiting its translation via a microRNA polycistron". PLOS Genetics. 3 (8): e146. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030146. PMC 1959363. PMID 17784791.

- Astrin SM, Laurence J (May 1992). "Human immunodeficiency virus activates c-myc and Epstein-Barr virus in human B lymphocytes". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 651 (1): 422–32. Bibcode:1992NYASA.651..422A. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24642.x. PMID 1318011. S2CID 31980333.

- Bernstein PL, Herrick DJ, Prokipcak RD, Ross J (April 1992). "Control of c-myc mRNA half-life in vitro by a protein capable of binding to a coding region stability determinant". Genes & Development. 6 (4): 642–54. doi:10.1101/gad.6.4.642. PMID 1559612.

- Iijima S, Teraoka H, Date T, Tsukada K (June 1992). "DNA-activated protein kinase in Raji Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Phosphorylation of c-Myc oncoprotein". European Journal of Biochemistry. 206 (2): 595–603. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16964.x. PMID 1597196.

- Seth A, Alvarez E, Gupta S, Davis RJ (December 1991). "A phosphorylation site located in the NH2-terminal domain of c-Myc increases transactivation of gene expression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266 (35): 23521–4. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)54312-X. PMID 1748630.

- Takahashi E, Hori T, O'Connell P, Leppert M, White R (1991). "Mapping of the MYC gene to band 8q24.12----q24.13 by R-banding and distal to fra(8)(q24.11), FRA8E, by fluorescence in situ hybridization". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 57 (2–3): 109–11. doi:10.1159/000133124. PMID 1914517.

- Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN (March 1991). "Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc". Science. 251 (4998): 1211–7. Bibcode:1991Sci...251.1211B. doi:10.1126/science.2006410. PMID 2006410.

- Gazin C, Rigolet M, Briand JP, Van Regenmortel MH, Galibert F (September 1986). "Immunochemical detection of proteins related to the human c-myc exon 1". The EMBO Journal. 5 (9): 2241–50. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04491.x. PMC 1167107. PMID 2430795.

- Lüscher B, Kuenzel EA, Krebs EG, Eisenman RN (April 1989). "Myc oncoproteins are phosphorylated by casein kinase II". The EMBO Journal. 8 (4): 1111–9. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03481.x. PMC 400922. PMID 2663470.

- Finver SN, Nishikura K, Finger LR, Haluska FG, Finan J, Nowell PC, Croce CM (May 1988). "Sequence analysis of the MYC oncogene involved in the t(8;14)(q24;q11) chromosome translocation in a human leukemia T-cell line indicates that putative regulatory regions are not altered". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 85 (9): 3052–6. Bibcode:1988PNAS...85.3052F. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.9.3052. PMC 280141. PMID 2834731.

- Showe LC, Moore RC, Erikson J, Croce CM (May 1987). "MYC oncogene involved in a t(8;22) chromosome translocation is not altered in its putative regulatory regions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 84 (9): 2824–8. Bibcode:1987PNAS...84.2824S. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.9.2824. PMC 304752. PMID 3033665.

- Guilhot S, Petridou B, Syed-Hussain S, Galibert F (December 1988). "Nucleotide sequence 3' to the human c-myc oncogene; presence of a long inverted repeat". Gene. 72 (1–2): 105–8. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(88)90131-X. PMID 3243428.

- Hann SR, King MW, Bentley DL, Anderson CW, Eisenman RN (January 1988). "A non-AUG translational initiation in c-myc exon 1 generates an N-terminally distinct protein whose synthesis is disrupted in Burkitt's lymphomas". Cell. 52 (2): 185–95. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90507-7. PMID 3277717. S2CID 3012009.

External links

[edit]- InterPro signatures for protein family: IPR002418, IPR011598, IPR003327

- The Myc Protein

- NCBI Human Myc protein

- Myc cancer gene

- myc+Proto-Oncogene+Proteins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Generating iPS Cells from MEFS through Forced Expression of Sox-2, Oct-4, c-Myc, and Klf4 Archived 2008-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Drosophila Myc - The Interactive Fly

- FactorBook C-Myc

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Human Myc proto-oncogene protein