Gangaridai

Gangaridai | |

|---|---|

| c. 300 BCE[1]–c. 2nd century CE [2] | |

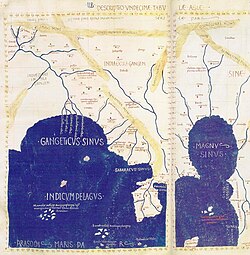

Ptolemy's Geography, depicting India beyond the Ganges | |

| Capital | Wari-Bateshwar or Chandraketugarh[1] |

| Government | Monarchy [citation needed] |

• King | Xandrames - After the establishment of the Nanda Dynasty |

| History | |

• Established | c. 300 BCE[1] |

• Disestablished | c. 2nd century CE [2] |

| Today part of | |

Gangaridai (Greek: Γαγγαρίδαι; Latin: Gangaridae) is a term used by the ancient Greco-Roman writers (1st century BCE-2nd century AD) to describe people or a geographical region of Bengal in the ancient Indian subcontinent. Some of these writers state that Alexander the Great withdrew from the Indian subcontinent because of the strong war elephant force of the Gangaridai.[1]

A number of modern scholars locate Gangaridai in the Ganges Delta of the Bengal region, although alternative theories also exist. Gange or Ganges, the capital of the Gangaridai (according to Ptolemy), has been identified with several sites in the region, including Chandraketugarh and Wari-Bateshwar.[3]

Independent Gangaridai

[edit]Not much is known about the independent state of Gangaridai and when it was independent however renowned Bengali historian, Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay, noted that during the rule of Chandragupta Maurya, the state of Gangaridai was independent.[2] The state of Gangaridai was established c. 300 BCE.

Establishment of the Nanda Dynasty

[edit]R.C Majumdar and D.C Sircar both argue that the Nanda dynasty was of Gangaridae (Bengali) origin. The Nanda's, are represented as the lord of both "Prasioi and the Gangaridai" or of Gangaridai alone. The description of Prasioi was a general name for the people of Eastern India, so the specific mention of Gangaridai attaches significance. The importance of Gangaridai or the Vanga people (Lower Bengal) may be explained by the suggestion of the Nanda dynasty belonging to them.[4][5]

The idea of the Bengali origin of the Nanda's can also be observed through Greek accounts of Xandrames (Greek for 'Nanda'). As Diodorus explicitly states, Plutarch affirms and Arrian evidently implies, Bengal had conquered Magadha.[5] This view is also compatible with the Puranic account and would explain the low position of these kings in the Puranas as Bengal was outside the domain of Aryan Culture during this time.[6]

Names

[edit]The Greek writers use the names "Gandaridae" (Diodorus), "Gandaritae", and "Gandridae" (Plutarch) to describe these people. The ancient Latin writers use the name "Gangaridae", a term that seems to have been coined by the 1st century poet Virgil.[7]

Some modern etymologies of the word Gangaridai split it as "Gaṅgā-rāṣṭra", "Gaṅgā-rāḍha" or "Gaṅgā-hṛdaya".[8] For example, it has been suggested that Gangarid is a Greek formation of the Indian word "Ganga-hṛd", meaning 'the land with the Ganges at its heart'. The meaning fits well with the description of the region given by the author of Periplus.[1] However, historian D. C. Sircar believes that the word is simply the plural form of "Gangarid" (derived from the base "Ganga"), and means "Ganga (Ganges) people".[8]

Some earlier scholars considered "Gangaridae" as a corruption of or distinct from "Gandaridae", a region they located in north-western part of the Indian subcontinent. For example, W. W. Tarn (1948) equated the term with Gandhara; and T.R. Robinson (1993) equated it to Gandaris or Gandarae, an area in present-day Punjab mentioned by ancient Greek writers. However, the ancient Greco-Roman works make it clear that Gandaridae was located in the Ganges plain: it was another name for Gangaridae, and was different from Gandhara and Gandaris.[9]

Greek accounts

[edit]Several ancient Greek writers mention Gangaridai, but their accounts are largely based on hearsay.[10]

Diodorus

[edit]

The earliest surviving description of Gangaridai appears in Bibliotheca historica of writer Diodorus Siculus (69 BCE-16AD). This account is based on a now-lost work, probably the writings of either Megasthenes or Hieronymus of Cardia.[11]

In Book 2 of Bibliotheca historica, Diodorus states that "Gandaridae" (i.e. Gangaridai) territory was located to the east of the Ganges river, which was 30 stades wide. He mentions that no foreign enemy had ever conquered Gandaridae, because it of its strong elephant force.[12] He further states that Alexander the Great advanced up to Ganges after subjugating other Indians, but decided to retreat when he heard that the Gandaridae had 4,000 elephants.[13]

This river [Ganges], which is thirty stades in width, flows from north to south and empties into the ocean, forming the boundary towards the east of the tribe of the Gandaridae, which possesses the greatest number of elephants and the largest in size. Consequently no foreign king has ever subdued this country, all alien nations being fearful of both the multitude and the strength of the beasts. In fact even Alexander of Macedon, although he had subdued all Asia, refrained from making war upon the Gandaridae alone of all peoples; for when he had arrived at the Ganges river with his entire army, after his conquest of the rest of the Indians, upon learning that the Gandaridae had four thousand elephants equipped for war he gave up his campaign against them.

In Book 17 of Bibliotheca historica, Diodorus once again describes the "Gandaridae", and states that Alexander had to retreat after his soldiers refused to take an expedition against the Gandaridae. The book (17.91.1) also mentions that a nephew of Porus fled to the land of the Gandaridae,[13] although C. Bradford Welles translates the name of this land as "Gandara".[15]

He [Alexander] questioned Phegeus about the country beyond the Indus River, and learned that there was a desert to traverse for twelve days, and then the river called Ganges, which was thirty-two furlongs in width and the deepest of all the Indian rivers. Beyond this in turn dwelt the peoples of the Tabraesians [misreading of Prasii[7]] and the Gandaridae, whose king was Xandrames. He had twenty thousand cavalry, two hundred thousand infantry, two thousand chariots, and four thousand elephants equipped for war. Alexander doubted this information and sent for Porus, and asked him what was the truth of these reports. Porus assured the king that all the rest of the account was quite correct, but that the king of the Gandaridae was an utterly common and undistinguished character, and was supposed to be the son of a barber. His father had been handsome and was greatly loved by the queen; when she had murdered her husband, the kingdom fell to him.

In Book 18 of Bibliotheca historica, Diodorus describes India as a large kingdom comprising several nations, the largest of which was "Tyndaridae" (which seems to be a scribal error for "Gandaridae"). He further states that a river separated this nation from their neighbouring territory; this 30-stadia wide river was the greatest river in this region of India (Diodorus does not mention the name of the river in this book). He goes on to mention that Alexander did not campaign against this nation, because they had a large number of elephants.[13] The Book 18 description is as follows:

…the first one along the Caucasus is India, a great and populous kingdom, inhabited by many Indian nations, of which the greatest is that of the Gandaridae, against whom Alexander did not make a campaign because of the multitude of their elephants. The river Ganges, which is the deepest of the region and has a width of thirty stades, separates this land from the neighbouring part of India. Adjacent to this is the rest of India, which Alexander conquered, irrigated by water from the rivers and most conspicuous for its prosperity. Here were the dominions of Porus and Taxiles, together with many other kingdoms, and through it flows the Indus River, from which the country received its name.

Diodorus' account of India in the Book 2 is based on Indica, a book written by the 4th century BCE writer Megasthenes, who actually visited India. Megasthenes' Indica is now lost, although it has been reconstructed from the writings of Diodorus and other later writers.[13] J. W. McCrindle (1877) attributed Diodorus' Book 2 passage about the Gangaridai to Megasthenes in his reconstruction of Indica.[17] However, according to A. B. Bosworth (1996), Diodorus' source for the information about the Gangaridai was Hieronymus of Cardia (354–250 BCE), who was a contemporary of Alexander and the main source of information for Diodorus' Book 18. Bosworth points out that Diodorus describes Ganges as 30 stadia wide; but it is well-attested by other sources that Megasthenes described the median (or minimum) width of Ganges as 100 stadia.[11] This suggests that Diodorus obtained the information about the Gandaridae from another source, and appended it to Megasthenes' description of India in Book 2.[13]

Plutarch

[edit]

Plutarch (46-120 CE) mentions the Gangaridai as "'Gandaritae" (in Parallel Lives - Life of Alexander 62.3) and as "Gandridae" (in Moralia 327b.).[7]

The Battle with Porus depressed the spirits of the Macedonians, and made them very unwilling to advance farther into India... This river [the Ganges], they heard, had a breadth of two and thirty stadia, and a depth of 1000 fathoms, while its farther banks were covered all over with armed men, horses and elephants. For the kings of the Gandaritai and the Prasiai were reported to be waiting for him (Alexander) with an army of 80,000 horse, 200,000 foot, 8,000 war-chariots, and 6,000 fighting elephants.

Other writers

[edit]

Ptolemy (2nd century CE), in his Geography, states that the Gangaridae occupied "all the region about the mouths of the Ganges".[19] He names a city called Gange as their capital.[20] This suggests that Gange was the name of a city, derived from the name of the river. Based on the city's name, the Greek writers used the word "Gangaridai" to describe the local people.[19]

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea does not mention the Gangaridai, but attests the existence of a city that the Greco-Romans described as "Ganges":

There is a river near it called the Ganges, and it rises and falls in the same way as the Nile. On its bank is a market-town which has the same name as the river, Ganges. Through this place are brought malabathrum and Gangetic spikenard and pearls, and muslin of the finest sorts, which are called Gangetic. It is said that there are gold-mines near these places, and there is a gold coin which is called caltis.

Dionysius Periegetes (2nd-3rd century CE) mentions "Gargaridae" located near the "gold-bearing Hypanis" (Beas) river. "Gargaridae" is sometimes believed to be a variant of "Gangaridae", but another theory identifies it with Gandhari people. A. B. Bosworth dismisses Dionysius' account as "a farrago of nonsense", noting that he inaccurately describes the Hypanis river as flowing down into the Gangetic plain.[22]

Gangaridai also finds a mention in Greek mythology. In Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica (3rd century BCE), Datis, a chieftain, leader of the Gangaridae who was in the army of Perses III, fought against Aeetes during the Colchian civil war.[23] Colchis was situated in modern-day Georgia, on the east of the Black Sea. Aeetes was the famous king of Colchia against whom Jason and the Argonauts undertook their expedition in search of the "Golden Fleece". Perses III was the brother of Aeetes and king of the Taurian tribe.

Roman accounts

[edit]The Roman poet Virgil speaks of the valour of the Gangaridae in his Georgics (c. 29 BCE).

On the doors will I represent in gold and ivory the battle of the Gangaridae and the arms of our victorious Quirinius.

Quintus Curtius Rufus (possibly 1st century CE) noted the two nations Gangaridae and Prasii:

Next came the Ganges, the largest river in all India, the farther bank of which was inhabited by two nations, the Gangaridae and the Prasii, whose king Agrammes kept in field for guarding the approaches to his country 20,000 cavalry and 200,000 infantry, besides 2,000 four-horsed chariots, and, what was the most formidable of all, a troop of elephants which he said ran up to the number of 3,000.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) states:

... the last race situated on its [Ganges'] banks being that of the Gangarid Calingae: the city where their king lives is called Pertalis. This monarch has 60,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry and 700 elephants always equipped ready for active service. [...] But almost the whole of the peoples of India and not only those in this district are surpassed in power and glory by the Prasi, with their very large and wealthy city of Palibothra [Patna], from which some people give the name of Palibothri to the race itself, and indeed to the whole tract of country from the Ganges.

Identification

[edit]

The ancient Greek writers provide vague information about the centre of the Gangaridai power.[10] As a result, the later historians have put forward various theories about its location.

Gangetic plains

[edit]Pliny (1st century CE) in his NH, terms the Gangaridai as the novisima gens (nearest people) of the Ganges river. It cannot be determined from his writings whether he means "nearest to the mouth" or "nearest to the headwaters". But the later writer Ptolemy (2nd century CE), in his Geography, explicitly locates the Gangaridai near the mouths of the Ganges.[22]

A. B. Bosworth notes that the ancient Latin writers almost always use the word "Gangaridae" to define the people, and associate them with the Prasii people. According to Megasthenes, who actually lived in India, the Prasii people lived near the Ganges. Besides, Pliny explicitly mentions that the Gangaridae lived beside the Ganges, naming their capital as Pertalis. All these evidences suggest that the Gangaridae lived in the Gangetic plains.[22]

The term Prasii is a transcription of the Sanskrit word prāchyas, literally "The Easterners".[27][28]

Rarh region

[edit]Diodorus (1st century BCE) states that the Ganges river formed the eastern boundary of the Gangaridai. Based on Diodorus's writings and the identification of Ganges with Bhāgirathi-Hooghly (a western distributary of Ganges), Gangaridai can be identified with the Rarh region in West Bengal.[10][29]

Larger part of Bengal

[edit]| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

The Rarh is located to the west of the Bhāgirathi-Hooghly (Ganges) river. However, Plutarch (1st century CE), Curtius (possibly 1st century CE) and Solinus (3rd century CE), suggest that Gangaridai was located on the eastern banks of the Gangaridai river.[10] Historian R. C. Majumdar theorized that the earlier historians like Diodorus used the word Ganga for the Padma River (an eastern distributary of Ganges).[10]

Pliny names five mouths of the Ganges river, and states that the Gangaridai occupied the entire region about these mouths. He names five mouths of Ganges as Kambyson, Mega, Kamberikon, Pseudostomon and Antebole. These exact present-day locations of these mouths cannot be determined with certainty because of the changing river courses. According to D. C. Sircar, the region encompassing these mouths appears to be the region lying between the Bhāgirathi-Hooghly River in the west and the Padma River in the east.[19] This suggests that the Gangaridai territory included the coastal region of present-day West Bengal and Bangladesh, up to the Padma river in the east.[30] Gaurishankar De and Subhradip De believe that the five mouths may refer to the Bidyadhari, Jamuna and other branches of Bhāgirathi-Hooghly at the entrance of Bay of Bengal.[31]

According to the archaeologist Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti, the centre of the Gangaridai power was located in vicinity of Adi Ganga (a now dried-up flow of the Hooghly river). Chakrabarti considers Chandraketugarh as the strongest candidate for the centre, followed by Mandirtala.[32] James Wise believed that Kotalipara in present-day Bangladesh was the capital of Gangaridai.[33] Archaeologist Habibullah Pathan identified the Wari-Bateshwar ruins as the Gangaridai territory.[34]

North-western India

[edit]William Woodthorpe Tarn (1948) identifies the "Gandaridae" mentioned by Diodorus with the people of Gandhara.[35] Historian T. R. Robinson (1993) locates the Gangaridai to the immediately east of the Beas River, in the Punjab region. According to him, the unnamed river described in Diodorus' Book 18 is Beas (Hyphasis); Diodorus misinterpreted his source, and incompetently combined it with other material from Megasthenes, erroneously naming the river as Ganges in Book 2.[36] Robinson identified the Gandaridae with the ancient Yaudheyas.[37]

A. B. Bosworth (1996) rejects this theory, pointing out that Diodorus describes the unnamed river in Book 18 as the greatest river in the region. But Beas is not the largest river in its region. Even if one excludes the territory captured by Alexander in "the region" (thus excluding the Indus River), the largest river in the region is Chenab (Acesines). Robison argues that Diodorus describes the unnamed river as "the greatest river in its own immediate area", but Bosworth believes that this interpretation is not supported by Diodorus's wording.[38] Bosworth also notes that Yaudheyas were an autonomous confederation, and do not match the ancient descriptions that describe Gandaridae as part of a strong kingdom.[37]

Other

[edit]According to Nitish K. Sengupta, it is possible that the term "Gangaridai" refers to the whole of northern India from the Beas River to the western part of Bengal.[10]

Pliny mentions the Gangaridae and the Calingae (Kalinga) together. One interpretation based on this reading suggests that Gangaridae and the Calingae were part of the Kalinga tribe, which spread into the Ganges delta.[39] N. K. Sahu of Utkal University identifies Gangaridae as the northern part of Kalinga.[40]

Political status

[edit]Diodorus mentions Gangaridai and Prasii as one nation, naming Xandramas as the king of this nation. Diodorus calls them "two nations under one king."[41] Historian A. B. Bosworth believes that this is a reference to the Nanda dynasty,[42] and the Nanda territory matches the ancient descriptions of kingdom in which the Gangaridae were located.[37]

According to Nitish K. Sengupta, it is possible that Gangaridai and Prasii are actually two different names of the same people, or closely allied people. However, this cannot be said with certainty.[41]

Historian Hem Chandra Raychaudhuri writes: "It may reasonably be inferred from the statements of the Greek and Latin writers that about the time of Alexander's invasion, the Gangaridai were a very powerful nation, and either formed a dual monarchy with the Pasioi [Prasii], or were closely associated with them on equal terms in a common cause against the foreign invader.[43]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Gangaridai - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ a b "The Historic State of Gangaridai". Bangladesh.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2024.

- ^ "History". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

Shah-i-Bangalah, Shah-i-Bangaliyan and Sultan-i-Bangalah

- ^ Sri Venkatesvara University, Oriental Research Institute (1979). Sri Venkateswara University Oriental Journal Volumes 21–22. p. 33.

- ^ a b Sircar, D.C. (1984). Journal of Ancient Indian History, Vol-14. p. 5.

- ^ R.C, Majumdar (1925). The early history of Bengal (PDF). Oxford University Press. p. 11.

- ^ a b c A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 75.

- ^ a b Dineschandra Sircar 1971, p. 171, 215.

- ^ A. B. Bosworth 1996, pp. 190–193.

- ^ a b c d e f Nitish K. Sengupta 2011, p. 28.

- ^ a b A. B. Bosworth 1996, pp. 188–189.

- ^ A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 188.

- ^ a b c d e A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 189.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus (1940). The Library of History of Diodorus Siculus. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. II. Translated by Charles Henry Oldfather. Harvard University Press. OCLC 875854910.

- ^ a b Diodorus Siculus (1963). The Library of History of Diodorus Siculus. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. VIII. Translated by C. Bradford Welles. Harvard University Press. OCLC 473654910.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus (1947). The Library of History of Diodorus Siculus. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. IX. Translated by Russel M. Geer. Harvard University Press. OCLC 781220155.

- ^ J. W. McCrindle 1877, pp. 33–34.

- ^ R. C. Majumdar 1982, p. 198.

- ^ a b c Dineschandra Sircar 1971, p. 172.

- ^ Dineschandra Sircar 1971, p. 171.

- ^ Wilfred H. Schoff (1912). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea; Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean. Longmans, Green and Co. ISBN 978-1-296-00355-5.

- ^ a b c A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 192.

- ^ Carlos Parada (1993). Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology. Åström. p. 60. ISBN 978-91-7081-062-6.

- ^ R. C. Majumdar 1982, pp. 103–128.

- ^ Pliny (1967). Natural History. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by H. Rackham. Harvard University Press. OCLC 613102012.

- ^ R. C. Majumdar 1982, p. 341-343.

- ^ Irfan Habib & Vivekanand Jha 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Karttunen, Klaus (Helsinki) (1 October 2006). "Prasii". Brill’s New Pauly. Brill.

- ^ Haldar, Narotam (1988). Gangaridi - Alochana O Parjalochana. pp. 43, 44, 49.

- ^ Ranabir Chakravarti 2001, p. 212.

- ^ Gourishankar De; Shubhradip De (2013). Prasaṅga, pratna-prāntara Candraketugaṛa. Scalāra. ISBN 978-93-82435-00-6.

- ^ Dilip K. Chakrabarti 2001, p. 154.

- ^ Jesmin Sultana 2003, p. 125.

- ^ Enamul Haque 2001, p. 13.

- ^ A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 191.

- ^ A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 190.

- ^ a b c A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 194.

- ^ A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 193.

- ^ Biplab Dasgupta 2005, p. 339.

- ^ N. K. Sahu 1964, pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b Nitish K. Sengupta 2011, pp. 28–29.

- ^ A. B. Bosworth 1993, p. 132.

- ^ Chowdhury, The History of Bengal Volume I, p. 44.

Sources

[edit]- A. B. Bosworth (1993). Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-1-107-71725-1.

- A. B. Bosworth (1996). Alexander and the East. Clarendon. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-19-158945-4.

- Biplab Dasgupta (2005). European Trade and Colonial Conquest. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-84331-029-7.

- Carlos Parada (1993). Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology. Åström. p. 60. ISBN 978-91-7081-062-6.

- Dilip K. Chakrabarti (2001). Archaeological Geography of the Ganga Plain: The Lower and the Middle Ganga. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-7824-016-9.

- Dineschandra Sircar (1971). Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0690-0.

- Enamul Haque (2001). Excavation at Wari-Bateshwar: A Preliminary Study. International Center for Study of Bengal Art. ISBN 978-984-8140-02-4.

- J. W. McCrindle (1877). Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian. London: Trübner & Co.

- Jesmin Sultana (2003). Sirajul Islam; Ahmed A. Jamal (eds.). Banglapedia: Kotalipara. Vol. 6. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-32-0581-0.

- N. K. Sahu (1964). History of Orissa from the Earliest Time Up to 500 A.D. Utkal University.

- Nitish K. Sengupta (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-341678-4.

- Ranabir Chakravarti (2001). Trade in Early India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-564795-2.

- R. C. Majumdar (1982). The Classical Accounts of India, Greek and Roman. South Asia Books. ISBN 978-0-8364-0858-4.

- Irfan Habib; Vivekanand Jha (2004). Mauryan India. A People's History of India. Aligarh Historians Society / Tulika Books. ISBN 978-81-85229-92-8.