René Girard

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (October 2024) |

René Girard | |

|---|---|

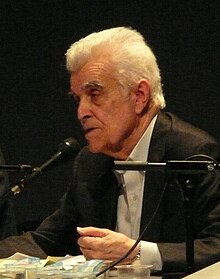

Girard in 2007 | |

| Born | René Noël Théophile Girard 25 December 1923 Avignon, France |

| Died | 4 November 2015 (aged 91) Stanford, California, U.S. |

| Education | École Nationale des Chartes (MA) Indiana University Bloomington (PhD) |

| Known for | Fundamental anthropology Mimetic theory Mimetic desire Mimetic double bind Scapegoat mechanism as the origin of sacrifice and foundation of human culture Girard's theory of group conflict |

| Spouse | Martha Girard[1] |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | Académie française (Seat 37) Knight of the Légion d’honneur Commandeur of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Duke University, Bryn Mawr College, Johns Hopkins University, State University of New York at Buffalo, Stanford University |

| Doctoral students | Sandor Goodhart |

| Other notable students | Andrew Feenberg |

| Signature | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

René Noël Théophile Girard (/ʒɪəˈrɑːrd/;[2] French: [ʒiʁaʁ]; 25 December 1923 – 4 November 2015) was a French historian, literary critic, and philosopher of social science whose work belongs to the tradition of philosophical anthropology. Girard was the author of nearly thirty books, with his writings spanning many academic domains. Although the reception of his work is different in each of these areas, there is a growing body of secondary literature on his work and his influence on disciplines such as literary criticism, critical theory, anthropology, theology, mythology, sociology, economics, cultural studies, and philosophy.

Girard's main contribution to philosophy, and in turn to other disciplines, was in the psychology of desire. Girard claimed that human desire functions imitatively, or mimetically, rather than arising as the spontaneous byproduct of human individuality, as much of theoretical psychology had assumed. Girard proposed that human development proceeds triangularly from a model of desire that indicates some object of desire as desirable by desiring it themselves. We copy this desire for the object of the model and appropriate it as our own, most often without recognizing that the source of this desire comes from another apart from ourselves completing the triangle of mimetic desire. This process of appropriation of desire includes (but is not limited to) identity formation, the transmission of knowledge and social norms, and material aspirations which all have their origin in copying the desires of others who we take, consciously or unconsciously, as models for desire.

The second major proposition of the mimetic theory proceeds from considering the consequences of the mimetic nature of desire as it relates to human origins and anthropology. The mimetic nature of desire allows for the anthropological success of human beings through social learning but is also laden with potential for violent escalation. If the subject desires an object simply because another subject desires it, then their desires are bound to converge on the same objects. If these objects cannot be easily shared (food, mates, territory, prestige and status, etc.), then the subjects are bound to come into mimetically intensifying conflict over these objects. The simplest solution to this problem of violence for early human communities was to polarize blame and hostility onto one member of the group who would be killed and interpreted as the source of conflict and hostility within the group. The transition from the violent conflict of all-against-all would be transformed into the unifying and pacifying violence of all-except-one whose death would reconcile the community together. The victim who was persecuted as the source of disorder would then become venerated as the source of order and meaning for the community and seen as a god. This process of engendering and making possible human community through arbitrary victimization is called, within mimetic theory, the scapegoat mechanism.

Eventually, the scapegoat mechanism would be exposed within the Biblical texts which categorically reorient the position of the Divinity to be on the side of the victim as opposed to that of the persecuting community. Girard argues that all other myths, such as Romulus and Remus, for example, are written and constructed from the point of view of the community whose legitimacy depends on the guilt of the victim in order to be brought together as a unified community. Once the relative innocence of the victim is exposed, the scapegoat mechanism is no longer able to function as a vehicle for generating unity and peace. The categorical moral innocence of Christ therefore serves to reveal the scapegoating mechanism in scripture, thus enabling the possibility that humanity might overcome it by learning to discern its continued presence in our interactions today.

Early life

[edit]Girard was born in Avignon on 25 December 1923.[a] René Girard was the second son of historian Joseph Girard.

He studied medieval history at the École des Chartes, Paris, where the subject of his thesis was "Private life in Avignon in the second half of the 15th century" ("La vie privée à Avignon dans la seconde moitié du XVe siècle").[3] [page needed]

In 1947, Girard went to Indiana University Bloomington on a one-year fellowship. He was to spend most of his career in the United States. He received his PhD in 1950 and stayed at Indiana University until 1953. The subject of his PhD at Indiana University was "American Opinion of France, 1940–1943".[3] Although his research was in history, he was also assigned to teach French literature, the field in which he would first make his reputation as a literary critic by publishing influential essays on such authors as Albert Camus and Marcel Proust.

Career

[edit]Girard occupied positions at Duke University and Bryn Mawr College from 1953 to 1957, after which he moved to Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he became a full professor in 1961. In that year, he also published his first book: Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque (Deceit, Desire and the Novel, 1966). For several years, he moved back and forth between the State University of New York at Buffalo and Johns Hopkins University. Books he published in this period include La Violence et le sacré (1972; Violence and the Sacred, 1977) and Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde (1978; Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, 1987).

In 1966, as the Chair of the Romance Languages Department at Johns Hopkins, Girard helped Richard A. Macksey, the Director of the newly founded Humanities Center, to organize a colloquium on French thought. The event was titled "The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man" and was held from 18 to 21 October 1966. Featuring prominent French academics such as Jacques Lacan, Roland Barthes, and Jacques Derrida, it is often credited with having launched the post-structuralist movement.

In 1981, Girard became Andrew B. Hammond Professor of French Language, Literature, and Civilization at Stanford University, where he stayed until his retirement in 1995. During this period, he published Le Bouc émissaire (1982), La route antique des hommes pervers (1985), A Theatre of Envy: William Shakespeare (1991) and Quand ces choses commenceront ... (1994).

In 1985, he received his first honorary degree from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands; several others followed.[citation needed]

In 1990, a group of scholars founded the Colloquium on Violence and Religion (COV&R) with the goal to "explore, criticize, and develop the mimetic model of the relationship between violence and religion in the genesis and maintenance of culture."[4][5] This organization organizes a yearly conference devoted to topics related to mimetic theory, scapegoating, violence, and religion. Girard was Honorary Chair of COV&R. Co-founder and first president of the COV&R was the Roman Catholic theologian Raymund Schwager.

René Girard's work has inspired interdisciplinary research projects and experimental research such as the Mimetic Theory project sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation.[6]

On 17 March 2005, Girard was elected to the Académie française.[7]

Girard's thought

[edit]Mimetic desire

[edit]After almost a decade of teaching French literature in the United States, Girard began to develop a new way of speaking about literary texts. Beyond the "uniqueness" of individual works, he looked for their common structural properties, having observed that characters in great fiction evolved in a system of relationships otherwise common to the wider generality of novels. But there was a distinction to be made:

Only the great writers succeed in painting these mechanisms faithfully, without falsifying them: we have here a system of relationships that paradoxically, or rather not paradoxically at all, has less variability the greater a writer is.[8]

Girard saw Proust's “psychological laws” mirrored in reality.[9] These laws and this system are the consequences of a fundamental reality grasped by the novelists, which Girard called mimetic desire, "the mimetic character of desire." This is the content of his first book, Deceit, Desire and the Novel (1961). We borrow our desires from others. Far from being autonomous, our desire for a certain object is always provoked by the desire of another person—the model—for this same object. This means that the relationship between the subject and the object is not direct: but unrolls within a triangular relationship of subject, model, and object. Through the model, one is drawn to the object.

In fact, it is the model, the mediator who is sought. This search is called "mediation."

Girard calls desire "metaphysical" in the measure that, as soon as a desire is something more than a simple need or appetite, "all desire is a desire to be",[8] it is an aspiration, the dream of a fullness attributed to the mediator.

Mediation is called "external" when the mediator of the desire is socially beyond the reach of the subject or, for example, a fictional character, as in the case of Amadis de Gaula and Don Quixote. The hero lives a kind of folly that nonetheless remains optimistic.

Mediation is called "internal" when the mediator is at the same level as the subject. The mediator then transforms into a rival and an obstacle to the acquisition of the object, whose value increases as rivalry grows.

This is the universe of the novels of Stendhal, Flaubert, Proust and Dostoevsky, which are particularly studied in this book.

Through their characters, our own behaviour is displayed. Everyone holds firmly to the illusion of the authenticity of one's own desires; the novelists implacably expose all the diversity of lies, dissimulations, manoeuvres, and the snobbery of the Proustian heroes; these are all but "tricks of desire", which prevent one from facing the truth: envy and jealousy. These characters, desiring the being of the mediator, project upon him superhuman virtues while at the same time depreciating themselves, making him a god while making themselves slaves, in the measure that the mediator is an obstacle to them. Some, pursuing this logic, come to seek the failures that are the signs of the proximity of the ideal to which they aspire. This can manifest as a heightened experience of the universal pseudo-masochism inherent in seeking the unattainable, which can, of course, turn into sadism should the actor play this part in reverse.[citation needed]

This fundamental focus on mimetic desire would be pursued by Girard throughout the rest of his career. The stress on imitation in humans was not a popular subject when Girard developed his theories,[citation needed] but today there is independent support for his claims coming from empirical research in psychology and neuroscience (see below). Farneti (2013)[10] also discusses the role of mimetic desire in intractable conflicts, using the case study of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and referencing Girard's theory. He posits that intensified conflict is a product of the imitative behaviours of Israelis and Palestinians, entitling them "Siamese twins".[11]

The idea that the desire to possess endless material wealth was harmful to society was not new. From the New Testament verses about the love of money being the root of all kinds of evil, to Hegelian and Marxist critique that saw material wealth and capital as the mechanism of alienation of the human being both from their own humanity and their community, to Bertrand Russell's famous speech on accepting the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1950, desire has been understood as a destructive force in all of literature – with the theft of Helen by Paris a frequent topic of discussion by Girard.[citation needed]

What Girard contributed to this concept is the idea that what is desired fundamentally is not the object itself, but the ontological state of the subject which possesses it, where mimicry is the aim of the competition.[citation needed] What Paris wanted, then, was not Helen, but to be a great king like Menelaus or Agamemnon.

A person desires to be like the subject he imitates through the medium of the object that is possessed by the person he imitates. Girard claims:

It is not difference that dominates the world, but the obliteration of difference by mimetic reciprocity, which itself, being truly universal, shows the relativism of perpetual difference to be an illusion.[12]

This was, and remains, a pessimistic view of human life, as it posits a paradox in the very act of seeking to unify and have peace, since the erasure of differences between people through mimicry is what creates conflict, not the differentiation itself.[citation needed]

Fundamental anthropology

[edit]Since the mimetic rivalry that develops from the struggle for the possession of the objects is contagious, it leads to the threat of violence. Girard himself says, "If there is a normal order in societies, it must be the fruit of an anterior crisis."[13] Turning his interest towards the anthropological domain, Girard began to study anthropological literature and proposed his second great hypothesis: the scapegoat mechanism, which is at the origin of archaic religion and which he sets forth in his second book Violence and the Sacred (1972), a work on fundamental anthropology.[14]

If two individuals desire the same thing, there will soon be a third, then a fourth. This process quickly snowballs. Since from the beginning desire is aroused by the other (and not by the object) the object is soon forgotten and the mimetic conflict transforms into a general antagonism. At this stage of the crisis the antagonists will no longer imitate each other's desires for an object, but each other's antagonism. They wanted to share the same object, but now they want to destroy the same enemy.

So, a paroxysm of violence will then focus on an arbitrary victim and a unanimous antipathy would, mimetically, grow against him. The brutal elimination of the victim will reduce the appetite for violence that possessed everyone a moment before, and leave the group, suddenly appeased and calm. The victim lies before the group, appearing simultaneously as the origin of the crisis and as the one responsible for this miracle of renewed peace. He becomes sacred, that is to say the bearer of the prodigious power of defusing the crisis and bringing peace back.

Girard believes this to be the genesis of archaic religion, that is, ritual sacrifice as the repetition of the original event, of myth as an account of this event, of the taboos that forbid access to all the objects at the origin of the rivalries that degenerated into this absolutely traumatizing crisis. This religious elaboration takes place gradually over the course of the repetition of the mimetic crises whose resolution brings only temporary peace. The elaboration of the rites and of the taboos constitutes a kind of "empirical" knowledge about violence.[citation needed]

Explorers and anthropologists have never been able to witness or bring true evidence for events similar to these, which go back to the earliest times. Yet 'indirect evidence' can be found, such as the universality of ritual sacrifice and the innumerable myths that have been collected from the most varied peoples. If Girard's theory is true, then we will find in myths the culpability of the victim-god, depictions of the selection of the victim and his power to beget the order that governs the group.

Girard found these elements in numerous myths, beginning with that of Oedipus which he analyzed in this and later books. On this question he opposes Claude Lévi-Strauss.[citation needed]

The phrase "scapegoat mechanism" was not coined by Girard himself; it had been used earlier by Kenneth Burke in Permanence and Change (1935) and A Grammar of Motives (1940). However, Girard took this concept from Burke and developed it much more extensively as an interpretation of human culture.[citation needed]

In Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978), Girard develops the implications of this discovery. The victimary process is the missing link between the animal world and the human world, the principle that explains the humanization of primates.

It allows us to understand the need for sacrificial victims, which in turn explains the hunt which is primitively ritual and the domestication of animals as a fortuitous result of the acclimatization of a reserve of victims, or agriculture. It shows that at the beginning of all culture is archaic religion, which Durkheim had sensed.[15] The elaboration of the rites and taboos by proto-human or human groups would take infinitely varied forms while obeying a rigorous practical sense that we can detect: the prevention of the return of the mimetic crisis. So we can find in archaic religion the origin of all political or cultural institutions.

The social position of king, for instance, begins as the victim of the scapegoat mechanism, though his sacrifice is deferred and he becomes responsible for the wellbeing of the whole society.

According to Girard, just as the theory of natural selection of species is the rational principle that explains the immense diversity of forms of life, the victimization process is the rational principle that explains the origin of the infinite diversity of cultural forms.

The analogy with Charles Darwin also extends to the scientific status of the theory, as each of these presents itself as a hypothesis that is not capable of being proven experimentally, given the extreme amounts of time necessary for the production of the phenomena in question, but which imposes itself by its great explanatory power.

Origin of language

[edit]According to Girard, the origin of language is also related to scapegoating. After the first victim, after the murder of the first scapegoat, there were the first prohibitions and rituals, but these came into being before representation and language, hence before culture. And that means that "people" (perhaps not human beings) "will not start fighting again."[16] Girard says:

If mimetic disruption comes back, our instinct will tell us to do again what the sacred has done to save us, which is to kill the scapegoat. Therefore it would be the force of substitution of immolating another victim instead of the first. But the relationship of this process with representation is not one that can be defined in a clear-cut way. This process would be one that moves towards representation of the sacred, towards definition of the ritual as ritual and prohibition as prohibition. But this process would already begin prior the representation, you see, because it is directly produced by the experience of the misunderstood scapegoat.[16]

According to Girard, the substitution of an immolated victim for the first, is "the very first symbolic sign created by the hominids."[17] Girard also says this is the first time that one thing represents another thing, standing in the place of this (absent) one.

This substitution is the beginning of representation and language and also the beginning of sacrifice and ritual. The genesis of language and ritual is very slow and we must imagine that there are also kinds of rituals among the animals: "It is the originary scapegoating which prolongs itself in a process which can be infinitely long in moving from, how should I say, from instinctive ritualization, instinctive prohibition, instinctive separation of the antagonists, which you already find to a certain extent in animals, towards representation."[16]

Unlike Eric Gans, Girard does not think that there is an original scene during which there is "a sudden shift from non-representation to representation,"[16] or a sudden shift from animality to humanity.

According to the French sociologist Camille Tarot, it is hard to understand how the process of representation (i.e., symbolicity and language) actually occurs and he has called this a black box in Girard's theory.[18]

Girard also says:

One great characteristic of man is what they [the authors of the modern theory of evolution] call neoteny, the fact that the human infant is born premature, with an open skull, no hair and a total inability to fend for himself. To keep it alive, therefore, there must be some form of cultural protection, because in the world of mammals, such infants would not survive, they would be destroyed. Therefore there is a reason to believe that in the later stages of human evolution, culture and nature are in constant interaction.

The first stages of this interaction must occur prior to language, but they must include forms of sacrifice and prohibition that create a space of non-violence around the mother and the children which make it possible to reach still higher stages of human development. You can postulate as many such stages as are needed.

Thus, you can have a transition between ethology and anthropology which removes, I think, all philosophical postulates. The discontinuities would never be of such a nature as to demand some kind of sudden intellectual illumination.[16]

Judeo-Christian scriptures

[edit]Biblical text as a science of man

[edit]In Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, Girard discusses for the first time Christianity and the Bible. The Gospels ostensibly present themselves as a typical mythical account, with a victim-God lynched by a unanimous crowd, an event that is then commemorated by Christians through ritual sacrifice — a material re-presentation in this case — in the Eucharist. The parallel is perfect except for one detail: the truth of the innocence of the Victim is proclaimed by the text and the writer.

The mythical account is usually built on the lie of the guilt of the victim in as much as it is an account of the event seen from the viewpoint of the anonymous lynchers. This ignorance is indispensable to the efficacy of sacrificial violence.[19]

The evangelic "good news" clearly affirms the innocence of the victim, thus becoming, by attacking ignorance, the germ of the destruction of the sacrificial order on which the equilibrium of societies rests. Already the Old Testament shows this turning inside-out of the mythic accounts with regard to the innocence of the victims (Abel, Joseph, Job...), and the Hebrews were conscious of the uniqueness of their religious tradition.

Girard draws special attention to passages in the Book of Isaiah, which describe the suffering of the Servant of the Lord God at the hands of the entire community who emphasize his innocence (Isaiah 53, 2–9).[20]

By oppression and judgement he was taken away;

And as for his generation, who considered

That he was cut off from out of the land of the living,

Stricken for the transgression of my people?

And they made his grave with the wicked

And with a rich man in his death,

Although he had done no violence,

And there was no deceit in his mouth. (Isaiah 53, 8–9)

In the Gospels, the "things hidden since the foundation of the world" (Matthew 13:35) are unveiled with full clarity: the foundation of social order on murder, described in all its repulsive ugliness in the account of the Passion.[citation needed]

This revelation is even clearer because the whole text is a work on desire and violence, from the desire of Eve in paradise to the prodigious strength of the mimetism that brings about the denial of Peter at Pesach (Mark 14: 66–72; Luke 22:54–62).

Girard reinterprets certain biblical expressions in light of his theories; for instance, he sees "scandal" (skandalon, literally, a "snare", or an "impediment placed in the way and causing one to stumble or fall"[21]) as signifying mimetic rivalry, as in Peter's denial of Jesus.[22] No one escapes responsibility, neither the envious nor the envied: "Woe to the man through whom scandal comes" (Matthew 18:7).[citation needed]

Christian society

[edit]The evangelical revelation contains the truth on the violence, available for two thousand years, Girard tells us. Has it put an end to the sacrificial order based on violence in the society that has claimed the gospel text as its own religious text? No, he replies, for in order for a truth to have an impact it must find a receptive listener, and people do not change quickly. The gospel text has instead acted as a ferment that brings about the decomposition of the sacrificial order. While medieval Europe showed the face of a sacrificial society that still knew very well how to despise and ignore its victims, nonetheless the efficacy of sacrificial violence has never stopped decreasing, in the measure that ignorance receded. Here Girard sees the principle of the uniqueness and of the transformations of the Western society whose destiny today is one with that of human society as a whole.[citation needed]

Does the retreat of the sacrificial order mean less violence? Not at all; rather, it deprives modern societies of most of the capacity of sacrificial violence to establish temporary order. The "innocence" of the time of the ignorance is no more. On the other hand, Christianity, following the example of Judaism, has desacralized the world, making possible a utilitarian relationship with nature. Increasingly threatened by the resurgence of mimetic crises on a grand scale, the contemporary world is on one hand more quickly caught up by its guilt, and on the other hand has developed such a great technical power of destruction that it is condemned to both more and more responsibility and less and less innocence.[23] So, for example, while empathy for victims manifests progress in the moral conscience of society, it nonetheless also takes the form of a competition among victims that threatens an escalation of violence.[citation needed] Girard is critical of the optimism of humanist observers, who believe in the natural goodness of man and the progressive improvement of his historical conditions (views themselves based in a misunderstanding of the Christian revelation). Rather, the current nuclear stalemate between the great powers reveals that man's capacity for violence is greater than ever before, and peace is only a product of this possibility to unleash apocalyptic destruction.[24]

Influence

[edit]Economics and globalization

[edit]The mimetic theory has also been applied in the study of economics, most notably in La violence de la monnaie (1982) by Michel Aglietta and André Orléan. Orléan was also a contributor to the volume René Girard in Les cahiers de l'Herne ("Pour une approche girardienne de l'homo oeconomicus").[25] According to the philosopher of technology Andrew Feenberg:

In La violence de la monnaie, Aglietta and Orléan follow Girard in suggesting that the basic relation of exchange can be interpreted as a conflict of 'doubles', each mediating the desire of the Other. Like Lucien Goldmann, they see a connection between Girard's theory of mimetic desire and the Marxian theory of commodity fetishism. In their theory, the market takes the place of the sacred in modern life as the chief institutional mechanism stabilizing the otherwise explosive conflicts of desiring subjects.[26]

In an interview with the Unesco Courier, anthropologist and social theorist Mark Anspach (editor of the René Girard issue of Les Cahiers de l'Herne) explains that Aglietta and Orléan (who were very critical of economic rationality) see the classical theory of economics as a myth. According to Anspach, the vicious circle of violence and vengeance generated by mimetic rivalry gives rise to the gift economy, as a means to overcome it and achieve peaceful reciprocity: "Instead of waiting for your neighbour to come steal your yams, you offer them to him today, and it is up to him to do the same for you tomorrow. Once you have made a gift, he is obliged to make a return gift. Now you have set in motion a positive circularity."[27] Since the gift may be so large as to be humiliating, a second stage of development—"economic rationality"—is required: this liberates the seller and the buyer of any other obligations than to give money. Thus reciprocal violence is eliminated by the sacrifice, obligations of vengeance by the gift, and finally the possibly dangerous gift by "economic rationality." This rationality, however, creates new victims, as globalization is increasingly revealing.

Literature

[edit]Girard's influence extends beyond philosophy and social science, and includes the literary realm. A prominent example of a fiction writer influenced by Girard is J. M. Coetzee, winner of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Literature. Critics have noted that mimetic desire and scapegoating are recurring themes in Coetzee's novels Elizabeth Costello and Disgrace. In the latter work, the book's protagonist also gives a speech about the history of scapegoating with noticeable similarities to Girard's view of the same subject. Coetzee has also frequently cited Girard in his non-fiction essays, on subjects ranging from advertising to the Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.[28]

Theology

[edit]Theologians who describe themselves as indebted to Girard include James Alison (who focuses on mimetic desire's implications for the doctrine of original sin), and Raymund Schwager (who builds a dramatic narrative around both the scapegoat mechanism and the theo-drama of fellow Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar).

Criticism

[edit]Originality

[edit]Some critics have pointed out that while Girard may be the first to have suggested that all desire is mimetic, he is by no means the first to have noticed that some desire is mimetic – Gabriel Tarde's book Les lois de l'imitation (The Laws of Imitation) appeared in 1890. Building on Tarde, crowd psychology, Nietzsche, and more generally on a modernist tradition of the "mimetic unconscious" that had hypnosis as its via regia, Nidesh Lawtoo argued that for the modernists not only desire but all affects turn out to be contagious and mimetic.[29] René Pommier[30] mentions La Rochefoucauld, a seventeenth-century thinker who already wrote that "Nothing is so infectious as example" and that "There are some who never would have loved if they never had heard it spoken of."[31]

Stéphane Vinolo sees Baruch Spinoza and Thomas Hobbes as important precursors. Hobbes: "if any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies."[32] Spinoza: "By the very fact that we conceive a thing, which is like ourselves, and which we have not regarded with any emotion, to be affected with any emotion, we are ourselves affected with a like emotion.[33] Proof… If we conceive anyone similar to ourselves as affected by any emotion, this conception will express a modification of our body similar to that emotion."[34]

Wolfgang Palaver adds Alexis de Tocqueville to the list. "Two hundred years after Hobbes, the French historian Alexis de Tocqueville mentioned the dangers coming along with equality, too. Like Hobbes, he refers to the increase of mimetic desire coming along with equality."[35] Palaver has in mind passages like this one, from Tocqueville's Democracy in America: "They have swept away the privileges of some of their fellow creatures which stood in their way, but they have opened the door to universal competition; the barrier has changed its shape rather than its position."[36]

Maurizio Meloni highlights the similarities between Girard, Jacques Lacan and Sigmund Freud.[37] Meloni claims that these similarities arise because the projects undertaken by the three men—namely, to understand the role of mythology in structuring the human psyche and culture—were very similar. What is more, both Girard and Lacan read these myths through the lens of structural anthropology so it is not surprising that their intellectual systems came to resemble one another so strongly. Meloni writes that Girard and Lacan were "moved by similar preoccupations and are fascinated by and attracted to the same kind of issues: the constituent character of the other in the structure of desire, the role of jealousy and rivalry in the construction of the social bond, the proliferation of triangles within apparently dual relations, doubles and mirrors, imitation and the Imaginary, and the crisis of modern society within which the 'rite of Oedipus' is situated."

At times, Girard acknowledges his indebtedness to such precursors, including Tocqueville.[38] At other times, however, Girard makes stronger claims to originality, as when he says that mimetic rivalry "is responsible for the frequency and intensity of human conflicts, but strangely, no one ever speaks of it."[39]

Use of evidence

[edit]Girard has presented his view as being scientifically grounded: "Our theory should be approached, then, as one approaches any scientific hypothesis."[40] René Pommier has written a book about Girard with the ironic title Girard Ablaze Rather Than Enlightened in which he asserts that Girard's readings of myths and Bible stories—the basis of some of his most important claims—are often tendentious. Girard notes, for example, that the disciples actively turn against Jesus.[41] Since Peter warms himself by a fire, and fires always create community, and communities breed mimetic desire, this means that Peter becomes actively hostile to Jesus, seeking his death.[42] According to Pommier, Girard claims that the Gospels present the Crucifixion as a purely human affair, with no indication of Christ dying for the sins of mankind, a claim contradicted by Mark 10:45 and Matthew 20:28.[43]

The same goes for readings of literary texts, says Pommier. For example, Molière's Don Juan only pursues one love object for mediated reasons,[44] not all of them, as Girard claims.[45] Or again, Sancho Panza wants an island not because he is catching the bug of romanticism from Don Quixote, but because he has been promised one.[46] And Pavel Pavlovitch, in Dostoevsky's Eternal Husband, has been married for ten years before Veltchaninov becomes his rival, so Veltchaninov is not in fact essential to Pavel's desire.[47]

Accordingly, a number of scholars have suggested that Girard's writings are metaphysics rather than science. Theorist of history Hayden White did so in an article titled "Ethnological 'Lie' and Mystical 'Truth'";[48] Belgian anthropologist Luc de Heusch made a similar claim in his piece "L'Evangile selon Saint-Girard" ("The Gospel according to Saint Girard");[49] and Jean Greisch sees Girard's thought as more or less a kind of Gnosis.[50]

Non-mimetic desires

[edit]René Pommier has pointed out a number of problems with the Girardian claim that all desire is mimetic. First, it is very hard to explain the existence of taboo desires, such as homosexuality in repressive societies, on that basis.[51] Second, every situation presents large numbers of potential mediators, which means that the individual has to make a choice among them; either authentic choice is possible, then, or else the theory leads to a regress.[52] Third, Girard leaves no room for innovation: Surely somebody has to be the first to desire a new object, even if everyone else follows that trend-setter.[53]

One might also argue that the last objection ignores the influence of an original sin from which all others follow, which Girard clearly affirms. However, original sin, according to Girard's interpretation, explains only our propensity to imitate, not the specific content of our imitated desires.[54] Thus, the doctrine of original sin does not solve the problem of how the original model first acquires the desire that is subsequently imitated by others.

Beneficial imitation

[edit]In the early part of Girard's career, there seemed no place for beneficial imitation. Jean-Michel Oughourlian objected that "imitation can be totally peaceful and beneficial; I don't believe that I am the other, I don't want to take his place. …This imitation can lead me to become sensitive to social and political problems."[55] Rebecca Adams argued that because Girard's theories fixated on violence, he was creating a "scapegoat" himself with his own theory: the scapegoat of positive mimesis. Adams proposed a reassessment of Girard's theory that includes an account of loving mimesis or, as she preferred to call it, creative mimesis.[56]

More recently, Girard has made room for positive imitation.[57] But as Adams implies, it is not clear how the revised theory accords with earlier claims about the origin of culture. If beneficial imitation is possible, then it is no longer necessary for cultures to be born by means of scapegoating; they could just as well be born through healthy emulation. Nidesh Lawtoo further develops the healthy side of mimetic contagion by drawing on a Nietzschean philosophical tradition that privileges "laughter" and other gay forms of "sovereign communication" in the formation of "community."[58]

Anthropology

[edit]Various anthropologists have contested Girard's claims. Elizabeth Traube, for example, reminds us that there are other ways of making sense of the data that Girard borrows from Evans-Pritchard and company—ways that are more consistent with the practices of the given culture. By applying a one-size-fits-all approach, Girard "loses … the ability to tell us anything about cultural products themselves, for the simple reason that he has annihilated the cultures which produced them."[59]

Religion

[edit]One of the main sources of criticism of Girard's work comes from intellectuals who claim that his comparison of Judeo-Christian texts vis-à-vis other religions leaves something to be desired.[60] There are also those who find the interpretation of the Christ event—as a purely human event, having nothing to do with redemption from sin—an unconvincing one, given what the Gospels themselves say.[43] Yet, Roger Scruton notes, Girard's account has a divine Jesus: "that Jesus was the first scapegoat to understand the need for his death and to forgive those who inflicted it … Girard argues, Jesus gave the best evidence … of his divine nature."[61]

Personal life

[edit]René Girard's wife, Martha (née McCullough), was American; they were married from 1952 until his death. They had two sons, Martin Girard (born 1955) and Daniel Girard (born 1957), and a daughter, Mary Brown-Girard (born 1960).[62]

Girard's reading of Dostoevsky, in preparation for his first book in 1961, converted him from agnosticism to Christianity. For the rest of his life, he was a practising Roman Catholic.[63]

On 4 November 2015, Girard died at his residence in Stanford, California, at the age of 91.[1]

Honours and awards

[edit]- Honorary degrees at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (the Netherlands, 1985), UFSIA in Antwerp (Belgium, 1995), the Università degli Studi di Padova (Italy, 2001, honorary degree in "Arts"),[64] the faculty of theology at the University of Innsbruck (Austria), the Université de Montréal (Canada, 2004),[65] and the University of St Andrews (UK, 2008)[66]

- The Prix Médicis essai for Shakespeare, les feux de l'envie (A Theatre of Envy: William Shakespeare, 1991)

- The prix Aujourd'hui for Les origines de la culture (2004)

- Guggenheim Fellow (1959 and 1966)[67]

- Election to the Académie française (2005)

- Awarded the Dr. Leopold Lucas Prize by the University of Tübingen (2006)[68]

- Awarded the Order of Isabella the Catholic, Commander by Number, by the Spanish head of state, H.M. King Juan Carlos

Bibliography

[edit]This section only lists book-length publications that René Girard wrote or edited. For articles and interviews by René Girard, the reader can refer to the database maintained at the University of Innsbruck. Some of the books below reprint articles (To Double Business Bound, 1978; Oedipus Unbound, 2004; Mimesis and Theory, 2008) or are based on articles (A Theatre of Envy, 1991).

- Girard, René (2001) [First published 1961], Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque [Romantic lie & romanesque truth] (in French) (reprint ed.), Paris: Grasset, ISBN 2-246-04072-8 (English translation: ——— (1966), Deceit, Desire and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-1830-3).

- ——— (1962), Proust: A Collection of Critical Essays, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- ——— (1963), Dostoïevski, du double à l'unité [Dostoievsky, from the double to the unity] (in French), Paris: Plon (English translation: ——— (1997), Resurrection from the Underground: Feodor Dostoevsky, Crossroad).

- 1972. La violence et le sacré. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 978-2-246-00051-8. (English translation: Violence and the Sacred. Translated by Patrick Gregory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8018-2218-1.) The reprint in the Pluriel series (1996; ISBN 2-01-008984-7) contains a section entitled "Critiques et commentaires", which reproduces several reviews of La Violence et le Sacré.

- 1976. Critique dans un souterrain. Lausanne: L'Age d'Homme. Reprint 1983, Livre de Poche: ISBN 978-2-253-03298-4. This book contains Dostoïevski, du double à l'unité and a number of other essays published between 1963 and 1972.

- 1978. "To double business bound": Essays on Literature, Mimesis, and Anthropology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-2114-1. This book contains essays from Critique dans un souterrain but not those on Dostoyevski.

- 1978. Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-61841-X. (English translation: Things Hidden since the Foundation of the World: Research undertaken in collaboration with Jean-Michel Oughourlian and G. Lefort. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987)

- 1982. Le bouc émissaire. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-26781-1. (English translation: The Scapegoat. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986)

- 1985. La route antique des hommes pervers. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-35111-1. (English translation: Job, the Victim of His People. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987)

- 1988. Violent Origins: Walter Burkert, Rene Girard, and Jonathan Z. Smith on Ritual Killing and Cultural Formation. Ed. by Robert Hamerton-Kelly. Palo Alto, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1518-1.

- 1991. A Theatre of Envy: William Shakespeare. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505339-7. The French translation, Shakespeare : les feux de l'envie, was published before the original English text.

- ——— (1994), Quand ces choses commenceront ... Entretiens avec Michel Treguer [When these things will begin... interviews with Michel Treguer] (in French), Paris: Arléa, ISBN 2-86959-300-7.

- 1996. The Girard Reader. Ed. by. James G. Williams. New York: Crossroad. ISBN 0-8245-1634-6.

- 1999. Je vois Satan tomber comme l'éclair. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 2-246-26791-9. (English translation: I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2001 ISBN 978-1-57075-319-0)

- ——— (2000), Um Longo Argumento do princípio ao Fim: Diálogos com João Cezar de Castro Rocha e Pierpaolo Antonello [A long argument from the start to the end: dialogues with João César de Castro Rocha and Pierpaolo Antonello] (in Portuguese), Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks, ISBN 85-7475-020-4 (French translation: ——— (2004), Les origines de la culture. Entretiens avec Pierpaolo Antonello et João Cezar de Castro Rocha [The origins of culture. Interviews with Pierpaolo Antonello & João César de Castro Rocha] (in French), Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, ISBN 978-2-220-05355-4. The French translation was upgraded in consultation with René Girard.[69] English translation: ——— (2008), Evolution and Conversion: Dialogues on the Origins of Culture, London: Continuum, ISBN 978-0-567-03252-2).

- ——— (2001), Celui par qui le scandale arrive: Entretiens avec Maria Stella Barberi [The one by whom scandal arrives: interviews with Maria Stella Barbieri] (in French), Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, ISBN 978-2-220-05011-9 (English translation: ——— (2014), The One by Whom Scandal Comes, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press).

- 2002. La voix méconnue du réel: une théorie des mythes archaïques et modernes. Paris: Grasset. ISBN 978-2-246-61101-1.

- 2003. Le sacrifice. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France. ISBN 978-2-7177-2263-5.

- 2004. Oedipus Unbound: Selected Writings on Rivalry and Desire. Ed. by Mark R. Anspach. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4780-6.

- 2006. Verità o fede debole. Dialogo su cristianesimo e relativismo. With Gianni Vattimo (English: Truth or Weak Faith). Dialogue about Christianity and Relativism. With Gianni Vattimo. A cura di P. Antonello, Transeuropa Edizioni, Massa. ISBN 978-88-7580-018-5

- 2006. Wissenschaft und christlicher Glaube Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007 ISBN 978-3-16-149266-2 (online: Knowledge and the Christian Faith)

- 2007. Dieu, une invention? Editions de l'Atelier. With André Gounelle and Alain Houziaux. ISBN 978-2-7082-3922-7.

- 2007. Le Tragique et la Pitié: Discours de réception de René Girard à l'Académie française et réponse de Michel Serres. Editions le Pommier. ISBN 978-2-7465-0320-5.

- 2007. De la violence à la divinité. Paris: Grasset. (Contains Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque, La violence et le Sacré, Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde and Le bouc émissaire, with a new general introduction). ISBN 978-2-246-72111-6.

- 2007. Achever Clausewitz. (Entretiens avec Benoît Chantre) Ed. by Carnets Nord. Paris. ISBN 978-2-35536-002-2.

- 2008. Anorexie et désir mimétique. Paris: L'Herne. ISBN 978-2-85197-863-9.

- 2008. Mimesis and Theory: Essays on Literature and Criticism, 1953–2005. Ed. by Robert Doran. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5580-1. This book brings together twenty essays on literature and literary theory.

- 2008. La conversion de l'art. Paris: Carnets Nord. (Book with DVD Le Sens de l'histoire, a conversation with Benoît Chantre) ISBN 978-2-35536-016-9.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Noël, his second name, is also French for "Christmas", the day on which he was born.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Haven, Cynthia (4 November 2015). "Stanford professor and eminent French theorist René Girard, member of the Académie Française, dies at 91". Stanford University. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "René Girard CBC interview part 1 of 5 (audio only)"

- ^ a b An excerpt from this thesis was reprinted in the René Girard issue of Les Cahiers de l'Herne (2008).

- ^ 'The rationale for and goals of "The Bulletin of the Colloquium on Violence & Religion"' COV&R-Bulletin No. 1 (September 1991)

- ^ "Constitution and By-Laws of the Colloquium on Violence and Religion" COV&R-Bulletin No. 6 (March 1994)

- ^ Imitation, Mimetic Theory, and Religions and Cultural Evolution – A Templeton Advanced Research Program, Mimetic theory.

- ^ "René GIRARD". Académie française.

- ^ a b Girard 1994, p. 32.

- ^ For example in Time Regained (Le Temps retrouvé, volume 7 of Remembrance of Things Past): "It is the feeling for the general in the potential writer, which selects material suitable to a work of art because of its generality. He only pays attention to others, however dull and tiresome, because in repeating what their kind say like parrots, they are for that very reason prophetic birds, spokesmen of a psychological law." In French: "...c'est le sentiment du général qui dans l'écrivain futur choisit lui-même ce qui est général et pourra entrer dans l'œuvre d'art. Car il n'a écouté les autres que quand, si bêtes ou si fous qu'ils fussent, répétant comme des perroquets ce que disent les gens de caractère semblable, ils s'étaient faits par là même les oiseaux prophètes, les porte-paroles d'une loi psychologique."

- ^ Farneti, Roberto (12 February 2013). "Bipolarity redux: the mimetic context of the 'new wars'". Cambridge Review of International Affairs. 26 (1): 181–202. doi:10.1080/09557571.2012.737305. S2CID 144739002. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Roberto Farneti, Mimetic politics (Michigan State University Press 2015), pages 34–38, 58–65, 69–71.

- ^ Girard, René, 1923–2015. (January 2014). The one by whom scandal comes. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-1-61186-109-9. OCLC 843010034.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Girard 1994, p. 29.

- ^ Thomas Ryba (ed.), René Girard and Creative Reconciliation, Lexington Books, 2014, page 19.

- ^ Durkheim, Emile (1915). The elementary forms of the religious life, a study in religious sociology. London: G. Allen & Unwin. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Müller, Markus (June 1996), "Interview with René Girard", Anthropoetics, II (1), retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Girard 2004, p. 157. "premier signe symbolique jamais inventé par les hominidés"

- ^ Tarot, Camille (2008), Le symbolique et le sacré [The symbolic & the sacred] (in French), Paris: La Découverte, p. 860.

- ^ Girard, Rene. Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. pp. 99–119.

- ^ Girard, Rene. Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. pp. 150–1.

- ^ "Skandalon", The New Testament Greek Lexicon, Study light.

- ^ Girard, René (April 1996), "Are the Gospels Mythical?", First Things.

- ^ Girard, Rene. Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. pp. 239–251.

- ^ Girard, Rene. Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. pp. 243–251.

- ^ René Girard, Cahier de L'Herne, pp. 261–65.

- ^ Feenberg, Andrew (1988), "Fetishism and Form: Erotic and Economic Disorder in Literature", in Dumouchel, Paul (ed.), Violence and Truth, Athlone Press & Stanford University Press, pp. 134–51.

- ^ Anspach, Mark (May 2001), Blanc, Yannick; Bessières, Michel (eds.), "Global markets, anonymous victims" (PDF), The UNESCO Courrier (interview), archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2008.

- ^ Andy Lamey, "Sympathy and Scapegoating in J. M. Coetzee," in J. M. Coetzee and Ethics: Philosophical Perspectives on Literature, Anton Leist and Peter Singer eds. (New York: Columbia University Press 2010). For Girard's influence on Coetzee, see pages 181–5.

- ^ Nidesh Lawtoo, The Phantom of the Ego: Modernism and the Mimetic Unconscious, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2013.

- ^ René Girard, Un allumé qui se prend pour un phare, Paris: Kimé, 2010, page 42

- ^ La Rochefoucauld, "Maxims," maxims 230, 136.

- ^ Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, I,13, World's classic, Oxford University Press, 1996, page 83. Quoted by S.Vinolo in S.Vinolo René Girard: du mimétisme à l'hominisation, pages 33–34

- ^ Ethica Ordine Geometrico Demonstrata Part. III Prop. XXVII : "Ex eo, quod rem nobis similem, et quam nullo affectu prosecuti sumus, aliquo affecti imaginamur, eo ipso simili affectu afficimur" quoted by Stéphane Vinolo, René Girard: du mimétisme à l'hominisation, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2005, page 20 ISBN 2-7475-9047-X. English translation H. M. Elwes's 1883 English translation The Ethics – Part III On the Origin and Nature of the Emotions Archived 2006-03-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ H. M. Elwes's 1883 English translation The Ethics – Part III On the Origin and Nature of the Emotions Archived 2006-03-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Wolfgang Palaver: De la violence: une approche mimétique Traduit de l'anglais par Paul Dumouchel. In Paul Dumouchel (Directeur), Comprendre pour agir: violences, victimes et vengeances. Paris: L'Harmattan, 2000, pages 89–110. ISBN 2-7637-7771-6 English version

- ^ Tocqueville, Alexis de (1835). "Causes Of The Restless Spirit Of Americans In The Midst Of Their Prosperity". Democracy in America. Vol. 2. Translated by Reeve, Henry. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ M Meloni: A Triangle of Thoughts: Girard, Freud, Lacan, Psychomedia [1]

- ^ René Girard. 1965. Deceit, Desire and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure Translated by Y. Freccero, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1965 page 120

- ^ René Girard. 2001. Celui par qui le scandale arrive: Entretiens avec Maria Stella Barberi. Paris: Desclée de Brouwer. page 19: "Dès que nous désirons ce que désire un modèle assez proche de nous dans le temps et dans l'espace, pour que l'objet convoité par lui passe à notre portée, nous nous efforçons de lui enlever cet objet | et la rivalité entre lui et nous est inévitable. C'est la rivalité mimétique. Elle peut atteindre un niveau d'intensité extraordinaire. Elle est responsable de la fréquence et de l'intensité des conflits humains, mais chose étrange, personne ne parle jamais d'elle."

- ^ René Girard, Violence and the Sacred, translated by Patrick Gregory, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977, page 316.

- ^ René Girard, Things Hidden since the Foundation of the World, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987, page 167.

- ^ René Pommier, "René Girard, Un allumé qui se prend pour un phare," Paris: Kimé, 2010, pages 98–102.

- ^ a b René Pommier, "René Girard, Un allumé qui se prend pour un phare," Paris: Kimé, 2010, pages 115–16.

- ^ René Pommier, "René Girard, Un allumé qui se prend pour un phare," Paris: Kimé, 2010, page 25.

- ^ René Girard. 1965. Deceit, Desire and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure Translated by Y. Freccero, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1965 page 51

- ^ René Pommier, "René Girard, Un allumé qui se prend pour un phare," Paris: Kimé, 2010, page 27.

- ^ René Pommier, "René Girard, Un allumé qui se prend pour un phare," Paris: Kimé, 2010, page 45.

- ^ Hayden White, "Ethnological 'Lie' and Mythical 'Truth'", Diacritics 8 (1978): 2–9, page 7.

- ^ Luc de Heusch: "L'Evangile selon Saint-Girard" Le Monde, 25 June 1982, page 19.

- ^ Jean Greisch "Une anthropologie fondamentale du rite: René Girard." in Le rite. Philosophie Institut catholique de Paris, présentation de Jean Greisch. Paris, Beauchesne, 1981.

- ^ René Pommier, "René Girard, Un allumé qui se prend pour un phare," Paris: Kimé, 2010, page 38.

- ^ René Pommier, "René Girard, Un allumé qui se prend pour un phare," Paris: Kimé, 2010, pages 33–34.

- ^ René Pommier, "René Girard, Un allumé qui se prend pour un phare," Paris: Kimé, 2010, page 18.

- ^ Girard, René [Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. Iep.utm.edu. Retrieved on 2013-10-23.

- ^ Jean-Michel Oughourlian: Genèse du désir. Paris: Carnets Nord, 2007, ISBN 978-2-35536-003-9. The French sentence goes: "L'imitation peut alors demeurer entièrement paisible et bénéfique; je ne me prends pas pour l'autre, je ne veux pas prendre sa place […] Cette imitation […] me conduira peut-être à me sensibiliser aux problèmes sociaux et politiques…

- ^ Adams, Rebecca (2000). "Loving Mimesis and Girard's "Scapegoat of the Text": A Creative Reassessment of Mimetic Desire" (PDF). Pandora Press US. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ René Girard, The Girard Reader, Trans. Yvonne Freccero, Ed. James G. Williams, New York: Crossroad Herder, 1996, pages 63–64, 269.

- ^ Nidesh Lawtoo. The Phantom of the Ego: Modernism and the Mimetic Unconscious. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2007, pages 284–304

- ^ Elizabeth Traube, "Incest and Mythology: Anthropological and Girardian Perspectives," The Berkshire Review 14 (1979): 37–54, pages 49–50

- ^ E.g. see the criticisms in Violence and Truth: On the Work of René Girard, Paul Dumouchel ed., Stanford University Press, 1988

- ^ Scruton, Roger (2014). The Soul of the World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 20.

- ^ Data derived from the biographical sketch provided by the Société des amis de Joseph & René Girard.

- ^ Andrade, Gabriel. "René Girard," Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Università degli Studie di Padova: Honoris causa degrees Archived 2007-04-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Marie-Claude Bourdon: La violence et le sacré: L'Université remet un doctorat honoris causa au penseur René Girard iForum volume 38 number 28 (19 April 2004)

- ^ University of St Andrews: Honorary degrees – June 2008 Archived 2015-04-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation: Fellows page: G Archived 2008-02-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Girard, René (2007). Wissenschaft und christlicher Glaube. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. p. 110. ISBN 978-3-16-149266-2.

- ^ Simonse, Simon (April 2005), "Review of René Girard, Les origines de la culture" (PDF), COV&R Bulletin (26): 10–11, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Aglietta, Michel & Orléan, André: La violence de la monnaie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (PUF), 1982. ISBN 2-13-037485-9.

- Alison, James (1998). The Joy of Being Wrong. Herder & Herder. ISBN 0-8245-1676-1.

- Anspach, Mark (Ed.; 2008). René Girard. Les Cahiers de l'Herne Nr. 89. Paris: L'Herne. ISBN 978-2-85197-152-4. A collection of articles by René Girard and a number of other authors.

- Bailie, Gil (1995). Violence Unveiled: Humanity at the Crossroads. Introduction by René Girard. New York: Crossroad. ISBN 0-8245-1645-1.

- Bellinger, Charles (2001). The Genealogy of Violence: Reflections on Creation, Freedom, and Evil. New York: Oxford. ISBN 0-19-513498-2.

- Bubbio, Paolo Diego (2018). Intellectual Sacrifice and Other Mimetic Paradoxes. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 97816118-627-3-7.

- Depoortere, Frederiek (2008). Christ in Postmodern Philosophy: Gianni Vattimo, Rene Girard, and Slavoj Zizek. London: Continuum. ISBN 0-567-03332-5.

- Doran, Robert (2012). "René Girard's Concept of Conversion and the Via Negativa: Revisiting Deceit, Desire and the Novel with Jean-Paul Sartre," Journal of Religion and Literature 43.3, 36–45.

- Doran, Robert (2011). "René Girard's Archaic Modernity," Revista de Comunicação e Cultura / Journal of Communication and Culture 11, pages 37–52.

- Dumouchel, Paul (Ed.; 1988). Violence and Truth: On the Work of René Girard. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1338-3.

- Fleming, Chris (2004). René Girard: Violence and Mimesis. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 0-7456-2948-2. This is an introduction to René Girard's work.

- Guggenberger, Wilhelm and Palaver, Wolfgang (Eds., 2013). René Girard’s Mimetic Theory and its Contribution to the Study of Religion and Violence, Special issue of the Journal of Religion and Violence, (Volume 1, Issue 2, 2013).

- Girard, René, and Sandor Goodhart. For René Girard: Essays in Friendship and in Truth. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2009.

- Golsan, Richard J. (1993). René Girard and Myth: An Introduction. New York & London: Garland. (Reprinted by Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-415-93777-9.)

- Hamerton-Kelly, Robert G. (1991). Sacred Violence: Paul's Hermeneutic of the Cross. Fortress Press. ISBN 0-8006-2529-3.

- Hamerton-Kelly, Robert G. & Johnsen, William (Eds.; 2008). Politics & Apocalypse (Studies in Violence, Mimesis, and Culture Series). Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87013-811-9.

- Harries, Jim. 2020. A Foundation for African Theology That Bypasses the West: The Writings of René Girard. ERT 44.2: pages 149–163.

- Haven, Cynthia L. Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard. Michigan State University Press, 2018. ISBN 1611862833 ISBN 978-1611862836

- Haven, Cynthia L. Conversations with René Girard: Prophet of Envy. Bloomsbury, 2020. ISBN 1350075167 ISBN 978-1350075160

- Heim, Mark (2006). Saved from Sacrifice: A Theology of the Cross. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-3215-6.

- Kirwan, Michael (2004). Discovering Girard. London: Darton, Longman & Todd. ISBN 0-232-52526-9. This is an introduction to René Girard's work.

- Lagarde, François (1994). René Girard ou la christianisation des sciences humaines. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-2289-4. This book is both an introduction and a critical discussion of Girard's work, starting with Girard's early articles on Malraux and Saint-John Perse, and ending with A Theatre of Envy.

- Lawtoo, Nidesh (2013). The Phantom of the Ego: Modernism and the Mimetic Unconscious. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 9781609173883

- Livingston, Paisley (1992). Models of Desire: René Girard and the Psychology of Mimesis. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4385-5.

- McKenna, Andrew J. (Ed.; 1985). René Girard and Biblical Studies (Semeia 33). Scholars Press. ISBN 99953-876-3-8.

- McKenna, Andrew J. (1992). Violence and Difference: Girard, Derrida, and Deconstruction. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06202-5.

- Mikolajewska, Barbara (1999). Desire Came upon that One in the Beginning... Creation Hymns of the Rig Veda. 2nd edition. New Haven: The Lintons' Video Press. ISBN 0-9659529-1-6.

- Mikolajewska, Barbara & Linton, F. E. J. (2004). Good Violence Versus Bad: A Girardian Analysis of King Janamejaya's Snake Sacrifice and Allied Events. New Haven: The Lintons' Video Press. ISBN 978-1-929865-29-1.

- Oughourlian, Jean-Michel. The Puppet of Desire: The Psychology of Hysteria, Possession, and Hypnosis, translated with an introduction by Eugene Webb (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991).

- Pommier, René (2010). René Girard, un allumé qui se prend pour un phare. Paris: Éditions Kimé. ISBN 978-2-84174-514-2.

- Palaver, Wolfgang (2013). René Girard's Mimetic Theory. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-1-61186-077-1.

- Swartley, William M. (Ed.; 2000). Violence Renounced: Rene Girard, Biblical Studies and Peacemaking. Telford: Pandora Press. ISBN 0-9665021-5-9.

- Tarot, Camille (2008). Le symbolique et le sacré. Paris: La Découverte. ISBN 978-2-7071-5428-6. This book discusses eight theories of religion, namely those by Émile Durkheim, Marcel Mauss, Mircea Eliade, George Dumézil, Claude Lévi-Strauss, René Girard, Pierre Bourdieu and Marcel Gauchet.

- Warren, James. Compassion or Apocalypse? (Winchester UK and Washington, USA: Christian Alternative Books, 2013 ISBN 978 1 78279 073 0)

- Webb, Eugene. Philosophers of Consciousness: Polanyi, Lonergan, Voegelin, Ricoeur, Girard, Kierkegaard (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1988)

- Webb, Eugene. The Self Between: From Freud to the New Social Psychology of France (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1993).

- Wallace, Mark I. & Smith, Theophus H. (1994). Curing Violence : Essays on Rene Girard. Polebridge Press. ISBN 0-944344-43-7.

- Williams, James G. The Bible, Violence, and Thee Sacred: Liberation from the Myth of Sanctioned Violence (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991)

- To Honor René Girard. Presented on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday by colleagues, students, friends (1986). Stanford French and Italian Studies 34. Saratoga, California: Anma Libri. ISBN 0-915838-03-6. This volume also contains a bibliography of Girard's writings before 1986.

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (November 2015) |

Bibliography

[edit]- Girard-Database: searchable database provided by the University of Innsbruck, Austria. Accessed 25 November 2008

- Regensburger, Dietmar. Bibliography of René Girard (1923–2015): The most detailed and up-to-date bibliography including weblinks, published in The Bulletin of the Colloquium on Violence and Religion volume 73 (August 2022). Accessed 16 September 2022

- The René Girard Bibliography. A short list of publications. Accessed 24 November 2008

Online videos of Girard

[edit]- Girard interviewed on "Uncommon Knowledge" at the Hoover Institution

- l'Immortel: A video short

- Stanford's Rene Girard on the source of human conflict

- BOOK TRAILER for Evolution of Desire: A life of René Girard: Conversation: René Girard and Cynthia L. Haven

- Full Length Documentary, "Things Hidden: The Life and Legacy of René Girard"

Interviews, articles and lectures by Girard

[edit]In chronological order.

- René Girard in Apostrophes, 16 June 1978, presenting his book Des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde on YouTube.

- René Girard: "Are the Gospels Mythical?" in First Things: A Journal of Religion, Culture, and Public Life, April 1996. See also "August/September Letters" in First Things: A Journal of Religion, Culture, and Public Life, August/ September 1996, for follow-up correspondence. Accessed 24 November 2008

- Girard lecture, on Violence, Victims and Christianity (Oxford 1997) Accessed 24 November 2008

- "What Is Occurring Today Is a Mimetic Rivalry on a Planetary Scale" Interview by Henri Tincq, Le Monde, 6 November 2001. Translated by Jim Williams. Original title: "Ce qui se joue aujourd'hui est une rivalité mimétique à l'échelle planétaire".

- "Violence & the Lamb Slain". Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity, December 2003. A short, accessible introduction to Girardian thought, plus an interview with Girard. Accessed 24 November 2008

- Ratzinger Is Right in New Perspectives Quarterly (NPQ) Volume 22, Number 3 (Summer 2005). On Pope Benedict XVI and relativism. Accessed 24 November 2008

- Interviews with Girard on mimetic desire (Saturday, September 17, 2005) and on ritual, myth, and religion (Tuesday, October 4, 2005) by Robert P. Harrison on Entitled Opinions. Accessed 24 November 2008

- Robert Doran: Apocalyptic Thinking after 9/11: An Interview with René Girard SubStance 115 (Volume 37, Number 1, 2008). Accessed 24 November 2008

- (in French) Centre Pompidou: Traces du sacré: René Girard, le sens de l'histoire Archived 2008-12-06 at the Wayback Machine. Excerpts from a conversation with Benoît Chantre (see La conversion de l'art). Accessed 24 November 2008

- Cynthia Haven, History is a test. Mankind Is Failing It., Stanford Magazine, July/ August 2009.

- Cynthia Haven, René Girard: Stanford's provocative immortel is a one-man institution, Stanford Report, 11 June 2008. Republished in The Book Haven as "René Girard @100: Stanford’s provocative immortel comes of age," 6 June 2023.

- Grant Kaplan, An Interview with René Girard, in First Things: A Journal of Religion, Culture, and Public Life, 6 November 2008.

- Cynthia Haven, "Christianity Will Be Victorious, But Only In Defeat": An Interview with René Girard, in First Things: A Journal of Religion, Culture, and Public Life, July 16, 2009.

- René Girard, "On War and Apocalypse" in First Things: A Journal of Religion, Culture, and Public Life, August/September 2009.

- The Scapegoat: René Girard's Anthropology of Violence and Religion: Interview with Girard on CBC's interview program Ideas, February 2011

Organizations inspired by mimetic theory

[edit]- Colloquium on Violence & Religion

- Association Recherches Mimétiques, founded in 2006.

- Imitatio, founded in 2008. Accessed 24 November 2008

- The Raven Foundation. This foundation "seeks to promote healing, hope, reconciliation and peace by offering insight into the dynamics of conflict and violence."

- Theology and Peace, founded in 2008. "An emerging movement seeking the transformation of theological practice through the application of mimetic theory."

- Preaching Peace, founded in 2002 as a website exploring the Christian lectionary from a mimetic theoretical perspective, 2007 organized as a non-profit in Pennsylvania committed to "Educating the church in Jesus' vision of peace."

Other resources

[edit]- Colloquium on Violence and Religion, Annual Conference 2004: Nature, Human Nature, and the Mimetic Theory. Some of the conference papers are available here. Accessed 24 November 2008

- Paul Nuechterlein: Girardian Reflections on the Lectionary: Understanding the Bible Anew Through the Mimetic Theory of René Girard Accessed 24 November 2008

- Philippe Cottet: On René Girard. Available in French and English. Accessed 24 November 2008

- Thomas A. Michael: How To Scapegoat the Leader. A Refresher Course (for those who do not need it). An introduction to Girard. Accessed 26 February 2013

- Joseph Bottum: "Girard among the Girardians" in First Things: A Journal of Religion, Culture, and Public Life, March 1996. A review of Violence Unveiled by Gil Bailie, The Sacred Game by Cesareo Bandera, The Gospel and the Sacred by Robert G. Hamerton-Kelly, and The Bible, Violence, and the Sacred by James G. Williams. Accessed 24 November 2008

- Paolo Diego Bubbio: "Mimetic Theory and Hermeneutics" in Colloquy 9 (2005). Accessed 26 February 2013

- University of St Andrews, UK: Honorary degree – June 2008. Archived 2015-04-07 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 26 February 2013

- Gerald J. Biesecker-Mast: "Reading Walter Wink's and Rene Girard's Religious Critiques of Violence as Communication Ethics." National Communication Association Annual Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, 20–23 November 1997. A short and clear explanation of the thought of Girard (principally) among other similar thoughts about people, violence and society.

- "Scapegoats and Sacrifices: Rene Girard". Australian Broadcasting Commission – Philosopher's Zone. Accessed 24 November 2008

- Trevor Merrill: "On War: Apocalypse and Conversion: Review Article on René Girard's Achever Clausewitz and Jean-Michel Oughourlian's Genèse du désir" in Lingua Romana: a journal of French, Italian and Romanian culture Volume 6, number 1 / fall 2007. Accessed 24 November 2008

- The website Preaching Peace contains a number of articles related to René Girard, for example:

- Per Bjørnar Grande: Girard's Christology (no date).

- Per Bjørnar Grande: Comparing Plato's Understanding of Mimesis to Girard's (no date).

- Matthew Pattillo: Violence, Anarchy and Scripture: Jacques Ellul and René Girard. Originally published in Contagion: Journal of Violence, Mimesis and Culture Volume 11, Spring 2004.Accessed 12 February 2009

- 1923 births

- 2015 deaths

- 20th-century French historians

- 20th-century French philosophers

- 21st-century French philosophers

- Commandeurs of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- Critical theorists

- Duke University faculty

- École Nationale des Chartes alumni

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism

- French Christian pacifists

- French literary critics

- French male writers

- French Roman Catholic writers

- Hermeneutists

- Indiana University Bloomington alumni

- Members of the Académie Française

- Mythographers

- Writers from Avignon

- Philosophers of social science

- Prix Médicis essai winners

- Catholic pacifists

- Catholic philosophers

- Christian apologists

- Stanford University Department of French and Italian faculty

- Winners of the Prix Broquette-Gonin (literature)

- Activists from Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur

- Philosophical anthropology