Full Throttle (1995 video game)

| Full Throttle | |

|---|---|

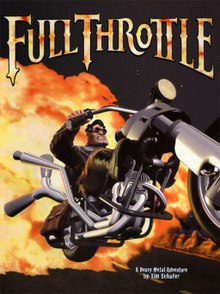

The cover art of Full Throttle, depicting protagonist Ben | |

| Developer(s) | LucasArts[a] |

| Publisher(s) | LucasArts (Original) Double Fine Productions (Remastered) Xbox Game Studios (Xbox Game Pass) |

| Designer(s) | Tim Schafer |

| Artist(s) | Peter Chan |

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | Peter McConnell |

| Engine | SCUMM |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Graphic adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Full Throttle is a 1995 graphic adventure video game developed by LucasArts and designed by Tim Schafer. It was Schafer's first game as project lead and head writer and designer, after having worked on other LucasArts titles including The Secret of Monkey Island (1990), Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge (1991), and Day of the Tentacle (1993). Set in the near future, the story follows motorcycle gang leader Ben, who must clear his name after being framed for the murder of a beloved motorcycle manufacturing mogul. A remastered version of the game was developed by Double Fine Productions and was released in April 2017 for Windows, PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita, with later ports for iOS and Xbox One.

Full Throttle was LucasArts' eleventh adventure game overall and the tenth to use the company's in-house game engine, SCUMM. It featured full-motion video and action sequences, using LucasArts' INSANE animation engine, which was previously utilized in Star Wars: Rebel Assault II: The Hidden Empire. It was the first LucasArts game to be distributed only on CD-ROM. as well as the last SCUMM game on MS-DOS. It also introduced a contextual pie menu through which the player controls interactions with objects and characters. In contrast to other computer games of the era, which mostly relied on in-house talent for their voice acting, Full Throttle used mostly professional voice actors, including Roy Conrad as Ben, Mark Hamill as the villainous Adrian Ripburger, Hamilton Camp as the elderly Malcolm Corley, and Kath Soucie as Ben's ally Maureen. It was one of the few LucasArts games to use licensed music, featuring songs by San Francisco-area rock band The Gone Jackals.[1]

Gameplay

[edit]

Full Throttle is a single-player video game in which the player controls the actions of the player character from a third-person perspective using a point and click interface. Players can move the player character to any place on the scene, interact with objects that are highlighted by the cursor, or leave scenes via exits - either on foot for most scenes, or via the character's motorbike, both types denoted by their own icon. As with other LucasArts graphic adventure games of the era, dialogue plays a large part in the game, presenting story elements and information necessary to advance, as well as fleshing out the characters. During conversations with other characters, several choices of dialogue are presented. The currently selected choice is highlighted, and once clicked, the player character responds with the selected choice. Choosing the correct response allows the player to advance the conversation and ultimately advance the scene.[2]

Following on from LucasArts' previous graphic adventure, Sam & Max Hit the Road (1993), which introduced a new inventory and interaction system to replace those of their prior games, Full Throttle continued to refine on the changes introduced in Sam & Max Hit the Road: objects or characters with which Ben can interact are indicated by a red square appearing around the cursor's crosshairs when it is placed over the object. When this occurs, holding down the control on this causes a contextual pie menu to appear - designed upon the emblem of Ben's biker gang: a flaming circle topped by a skull and flanked by a boot and a gloved hand. The player hovers the cursor over elements of the emblem and then releases the mouse button to attempt various interactions with the object; for example, selecting the skull's mouth to speak to a character, its eyes to examine an object, or the hand to pick up, use, or pull the object. Right-clicking anywhere on the screen brings up the player's inventory of collected objects, which can be examined or dragged and dropped in order to use them with other items in the inventory, or with objects or characters in the scene.[2]

Plot

[edit]The last domestic motorcycle manufacturer in the country is Corley Motors, whose founder and CEO, the elderly Malcolm Corley (Hamilton Camp), is en route to a shareholders meeting at the Corley factory, accompanied by his vice president, Adrian Ripburger (Mark Hamill). Malcolm suspects that Ripburger is scheming to take over the company, and is suspicious of Ripburger's plan to recruit a biker gang to ride with them to the meeting. Malcolm's limousine is overtaken by one such gang, the Polecats, and he is immediately impressed with them. Catching up to them at a biker bar, he quickly befriends their leader, Ben (Roy Conrad). Ripburger offers to hire the Polecats to escort Malcolm to the meeting, but when Ben declines, he is knocked out by Ripburger's flunkies, Bolus (Jack Angel) and Nestor (Maurice LaMarche).

Ben awakens to learn that the Polecats have been duped into escorting Malcolm, and that an ambush is planned for them further up the road. He tries to catch up, but his motorcycle has been sabotaged, resulting in a fiery crash. He is rescued by young photographer Miranda (Pat Musick) and taken to the town of Melonweed, where he is treated by a mechanic named Maureen (Kath Soucie). Maureen describes how her father taught her about motorcycles, and repairs Ben's bike after he retrieves necessary parts, adding a booster to it as well. Ben catches up to the Polecats at a rest area, but is too late: Ripburger murders Malcolm and frames the Polecats for the crime. Miranda manages to catch the murder on film, but her camera is snatched by Bolus. Before dying, Malcolm tells Ben of Ripburger's plan to take over Corley Motors and produce minivans instead of motorcycles. He reveals that Maureen is secretly his illegitimate daughter and begs Ben to convince her to take over the company. Bolus tries to kill Maureen, but she gets the drop on him and escapes with the film from Miranda's camera.

With the Polecats jailed for Malcolm's murder, Ben is a fugitive. Miranda tells him about her film, and Ben convinces semi-trailer truck driver Emmet to sneak him and his motorcycle past a police roadblock and to an abandoned mink farm where Maureen is hiding. He is stranded there when Emmet steals his motorcycle's fuel line and Maureen steals his booster fuel. Emmet's truck is blown up by a biker gang called the Cavefish, destroying the bridge over Poyahoga Gorge, which Ben needs to cross. Having replaced his fuel line and gotten advice from the Polecats' former leader, Father Torque (Hamilton Camp), Ben outwits Nestor and Bolus and does battle with members of rival biker gangs in order to acquire hover equipment, booster fuel, and a ramp, with which he is able to jump his motorcycle over the gorge.

Ben locates Maureen, who is a member of rival biker gang the Vultures, at the Vulture's hideout, a large cargo aircraft. Maureen believes Ben killed her father and is about to have him executed, but Ben reveals personal information that Malcolm shared with him and convinces her to develop Miranda's film, which shows that Ripburger was the murderer. Ben suggests exposing Ripburger at the shareholders meeting, but Ripburger has postponed the meeting until he is sure Ben and Maureen are dead. The Vultures come up with a plan to fake Ben and Maureen's deaths by entering them in a demolition derby under false identities that will be obvious to Ripburger. Their cars are rigged to explode, but Ben is protected by a fireproof suit and Maureen's car ejects her safely out of the stadium. The plan works and results in the deaths of Bolus and Nestor, while the Vultures recover the winner's prize: a special motorcycle built by Malcolm and Maureen that contains a hidden pass code to Malcolm's safe, in which Ben finds Malcolm's recorded will and testament. Ben exposes Ripburger during the shareholders meeting by projecting Miranda's photos of the murder and playing Malcolm's will, in which he leaves leadership of Corley Motors to Maureen and exposes Ripburger as a sham.

Ripburger flees in a semi-trailer truck, but as Ben and Maureen ride away he reappears and rams them. The Vultures arrive driving their flightless cargo plane, which scoops up the truck along with Ben, Maureen, and Ben's bike. The plane and truck wind up hanging precariously over the edge of Poyahoga Gorge, and Ripburger falls to his death. Maureen and the Vultures flee the plane while Ben makes it out at the last second by jumping his bike out the back cargo door just as the truck explodes and it and the plane fall into the gorge. Members of the biker gangs attend Malcolm's funeral, at which Father Torque delivers a eulogy. Maureen takes over Corley Motors, and Ben rides away into the sunset.

Development

[edit]The concept of Full Throttle originated following the 1993 release of LucasArts’ previous adventure game Day of the Tentacle.[2] The company wanted to create a game that could revitalize the genre,[3] and could offer LucasArts greater financial success than its earlier projects, such as the commercially unsuccessful Monkey Island series.[4] Convening its designers, LucasArts expressed to them the idea and encouraged the staff to suggest potential conceptual avenues for the game.[3] The company specifically asked Day of the Tentacle co-designers Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman to submit a design document outlining games that the two planned to develop afterward.[2] At LucasArts’ request, Schafer and Grossman collaborated to propose prospective third entries in the Monkey Island and Maniac Mansion series.[2] However, Schafer was willing to helm a project by himself,[5] and he proceeded to develop concepts separately from Grossman that summer.[2][6] Full Throttle was among the five concepts that Schafer submitted to LucasArts;[4] according to Schafer, he produced "a pitch for a spy game, a Day of the Dead game, and a biker game" that later evolved into Full Throttle.[7] Schafer later said that management "hated" the initial pitch, but he revised the design and repitched it with greater success.[8] Edge reported that "it was eventually greenlit on Schafer's assurance that it would be a hit", as he felt that its protagonist and concept were "more commercial" than the company's earlier adventures.[4]

According to Schafer, he came up with the idea for Full Throttle while listening to a traveller's tales about time spent in an Alaskan biker bar. As he listened, it occurred to him that "bikers are kind of like pirates — like another culture that people don't have a window into most of the time, but [which] has its own rules", and might provide a neat alternative to a fantasy setting. He began his research into biker culture, reading Hunter S. Thompson's Hell's Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs.[2] The game originally would have featured an interactive sequence where Ben undergoes a peyote-induced hallucinogenic trip. This was eventually cut from the game, because the developers couldn't get it to "work out" with the publisher. The concept eventually became the basis of Psychonauts.[9] Schafer recalls the reaction from the management at LucasArts as being one of "'We can't believe we paid you to write this'". "They hated it".[8] In an interview with Gamasutra, Schafer said that the biker aesthetics of the game were an appeal to fantasy. He stated that the team was depending "on the [player's] secret desire to be a biker: big, tough, cool. Riding a huge hog..."[10] On the game's setting he noted that often it was mistaken for a post apocalyptic world, but he clarified that the setting was simply an alternate world which was more desolate than our own.[2][b]

Developed for CD-ROM with a budget of $1.5 million,[12] Full Throttle was powered primarily by LucasArts' SCUMM engine, however elements of the company's INSANE animation engine, previously used in Star Wars: Rebel Assault II: The Hidden Empire, were also implemented so as to allow for improved full-motion video (FMV).[8] The game featured completely voiced dialogue, full-motion video, and a digital audio soundtrack. Project leader Schafer also served as the game's writer and designer. Full Throttle has thus been called Schafer's first "solo" project, leading Schafer to quip, "I did it all on my own with about 30 other people".[13] Production lasted one and a half years, which Schafer considered to be "crazy" for the era.[14]

Full Throttle employed several skilled voice acting professionals, such as Roy Conrad, Kath Soucie, Maurice LaMarche, Tress MacNeille, Hamilton Camp, Steven Jay Blum and Mark Hamill. Full Throttle was the first computer game to employ mostly SAG-registered professional voice actors instead of relying on in-house talent, and also featured a few pieces of licensed music. Schafer stated that Conrad's voice was a "huge part of making Ben Throttle a charming character".[8] It was one of the few LucasArts games to use externally recorded music, courtesy of The Gone Jackals. Certain tracks from their album, Bone to Pick, were featured in the game.[2]

Release

[edit]Full Throttle was released on May 19, 1995.[15] At the time of its release, LucasArts adventure games were aiming to sell about 100,000 copies; Full Throttle broke that mark by selling over one million units.[16][17] According to Edge, it was the very first LucasArts adventure to reach this number.[4]

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 86/100[18] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Adventure Gamers | |

| Computer Gaming World | |

| GameSpot | 8.7/10[21] |

| Next Generation | |

| PC Gamer (US) | 90%[23] |

| PC Magazine | |

| Macworld | |

| MacUser | |

| PC Games | A−[27] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| PC Games | Game of the Month[27] |

At aggregate review website Metacritic the game received generally favorable reviews,[18] and has over time become a cult classic among adventure games.[28] Critics generally praised the game's animation, voice acting and soundtrack, but many reviewers felt the game was too short.[22][23][24]

A Next Generation reviewer called Full Throttle "the kind of game the Mac was meant for" and "a sheer joy to behold, even if you loathed Monkey Island with a seething, purple passion". Citing the futuristic setting, "kick-butt" soundtrack, outstanding voice acting, understated humor, and overall cinematic presentation, the reviewer gave it four out of five stars.[22] Full Throttle later won Computer Gaming World's 1995 Readers' Choice award for "Adventure Game of the Year", although it was not among the editors' nominees.[29] PC Gamer's Steve Poole also praised the game's sound, citing both the inclusion of The Gone Jackals' music and the professional voice acting as points of high praise. Poole did note that puzzles can at times be too simple, with an aesthetic of "find item A to use on item B".[23] Commenting on the game's length, he noted that while short, "it's one wild ride while it lasts".[23] Bernard H. Yee of PC Magazine had similar thoughts in his review. He too felt the game was short, but praised the game's cartoon-like animation and visuals, voice acting and soundtrack. He noted that some adventure gamers might "grouse at the action-arcade fight sequences or grumble at the long narrative sequences" but felt that the game as "impressive and attention-grabbing".[24] PC Gamer US's editors later presented the game with a "Special Achievement in Musical Score" award, and argued that it "showed the world that every game can benefit greatly from a good musical score". The editors nominated Full Throttle as their 1995 "Best Adventure Game", although it lost to Beavis and Butt-Head in Virtual Stupidity.[30]

Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World felt that the puzzles were not challenging enough compared to similar games of the era. He did note that this was the "ideal starter game" for those players who were not comfortable with more complex and difficult puzzles.[20] Ardai stated that players experienced in the adventure genre could still enjoy the game by treating it as a "highly interactive movie".[20] Macworld's Tom Negrino felt that the new pie menu system was a refreshing change to the traditional adventure game interface. He also gave high marks for the lack of a game over sequence and noted that any time the player fails a sequence it simply resets. He further praised the game's writing, voice acting and soundtrack.[25] In a review for GameSpot Jeffrey Adam called Full Throttle "arguably LucasArts' finest graphic adventure creation".[21] Adam did note two flaws in his review. The first is during on-motorcycle action sequences with rival gang members, in which he notes that, even considering an unlimited number of attempts, the sequences relied too much on twitch responses. The second frustration Adam noted was that he felt sometimes he resorted to randomly clicking on whole areas of the screen in hopes of finding a clue. He felt that this method did not allow players to use deductive reasoning.[21]

The game's humor was praised by PC Gamer's Steve Poole for its many LucasFilm and other cultural references. Specifically he cited two Star Wars references in the game. The first is during the demolition derby sequence in which rival driver is illustrated to look like George Lucas. The second is during a scene where Ben is talking to the reporter, Miranda. She says "Help me Ben, you're my only hope!", a play on Princess Leia's dialogue to Obi-Wan Kenobi from Star Wars: A New Hope. Other references found by Poole were nods to the 1964 film Dr. Strangelove and the 1993 LucasArts adventure game Sam & Max Hit the Road.[23]

Entertainment Weekly gave the game a B+ and praised the soundtrack, and the humor.[1]

Full Throttle was the second-place finalist for Computer Game Review's 1995 "Adventure Game of the Year" award, which went to Mission Critical. The editors noted that "it had wonderful graphics, animation and voice work and the story was good, too".[31] It was also a finalist for MacUser's award for the best strategy game of 1995, which went to You Don't Know Jack.[32]

Legacy

[edit]Cancelled sequels

[edit]In spring 2000, LucasArts began production of Full Throttle 2, an official sequel to continue the storyline of Full Throttle.[33] Since Tim Schafer had already left the company at the time, Larry Ahern, who was involved in the original game's development, was appointed the project lead and Bill Tiller, the art director. The story would have focused on Ben's efforts to foil a plan by a "large corporation" and the local governor to replace all paved highways with hover pads, robbing the bikers and truckers of their traditional ground. In the first half of the game, Ben would have prevented an assassination attempt on Father Torque, who now leads the anti-hovercraft rally, then team up with a "persistent undercover female reporter" to bring down the villainous governor. In Tiller's opinion, the sequel "was going to capture the feel of the first game yet expand upon the milieu".[28] At the early stages, the project received positive feedback from other LucasArts employees but according to Tiller, it eventually fell apart because of disagreements on the game style between the production team and "a particularly influential person" within the management, which led to a series of "mistakes". The production ceased in November 2000, when 25% of the levels and about 40% of the preproduction art were complete. LucasArts never released an official statement regarding the game cancellation.[28] Both Ahern and Tiller left LucasArts in 2001, after the game was cancelled.

In mid-2002, LucasArts announced Full Throttle: Hell on Wheels for Windows and, for the first time, PlayStation 2 and Xbox. The game was to be an action-adventure, with more emphasis on action and fighting than adventure, because the designers wanted the game to feel more physical than the first.[34] Hell on Wheels would have been set in El Nada, Ben's "old stomping ground", whose roads have been mysteriously destroyed. Ben believes that one of the new gangs introduced in the game, the Hound Dogs, are behind this but soon discovers a more sinister and murderous plot. Together with Father Torque and Maureen, he would have thwarted the unnamed villain's plan and protected "the freedom of the open road".[28] Sean Clark was named the project lead of Hell on Wheels and the development progressed smoothly until late 2003, when it was abruptly canceled. Just months prior to that, at E3 2003, a playable demo was shown and a teaser trailer was released by LucasArts.[35] Simon Jeffery (then president of LucasArts) said that "We do not want to disappoint the many fans of Full Throttle, and hope everyone can understand how committed we are to delivering the best-quality gaming experience that we possibly can" in the official press release. Critics cited poor graphics compared to other 3D action adventures of the time and Tim Schafer's lack of involvement in the project as possible reasons for its cancellation.[28] Additionally, Roy Conrad, the original voice actor for Ben, died in 2002.[36]

Critics considered development of new sequels to Full Throttle unlikely. LucasArts' interest shifted away from the adventure genre in later years, and failure to develop two sequels presumably hindered the possibility of a third. Also, nearly all developers who were involved with the original Full Throttle in 1995 had since left LucasArts.[28] LucasArts ceased all internal development in 2013, shortly after their parent company Lucasfilm was purchased by The Walt Disney Company.[37] In a 2017 interview discussing the work on the remaster, Schafer said that he feels that the story of Full Throttle was essentially complete with the game, and does not envision creating a sequel himself.[16]

Remastered

[edit]A remastered version of Full Throttle, titled Full Throttle Remastered, was developed by Schafer's Double Fine Productions for release on Windows, OS X, Linux, PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita. The PlayStation 4 and PlayStation Vita versions are cross-buy[38] and cross-save.[39] The remastered version was released on April 18, 2017.[40] Like Day of the Tentacle Remastered and Grim Fandango Remastered, the remastered version of Full Throttle includes updated graphics and sound, improved controls, and developer commentary.[41] Similarly, the game allows the player to swap between the original graphics and sound with the remastered versions.[42][43][44][45]

The game uses the original voice actors' dialog pulled from the original recordings, with Schafer calling Conrad's voice "irreplaceable". The remastered version premiered at the 2017 Game Developers Conference, where Schafer presented a remaking of a magazine pack-in demo that included recorded lines that had not been included in the full game.[46] Schafer said that fans had been critical of Full Throttle's relatively short length of about eight hours compared to other LucasArts games at the time which could take up to 40 hours. However, as he worked at the remaster, player expectations have changed, and he felt that Full Throttle would be much better suited at its length in 2017, comparing it to other fully polished, short games like Inside.[16]

A port for the Xbox One was released on October 29, 2020.[47]

Potential film adaptation

[edit]Duncan Jones had written a screenplay based on Full Throttle in 2021,[48] and reached out to fans of the game in 2022 to try to help convince Disney to fund production of the work for the Disney+ service.[49]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Full Throttle". EW.com. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Tim Schafer Plays "Full Throttle" Part 1". Double Fine Adventure!. Double Fine Productions. October 5, 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ a b Steele, Jake (host) (April 28, 2005). "Tim Schafer". Icons. Episode 5004. G4TV. Archived from the original on November 8, 2005.

- ^ a b c d Staff (August 2009). "Master of Unreality". Edge. No. 204. United Kingdom: Future Publishing. pp. 82–87.

- ^ "In the Chair with Tim Schafer". Retro Gamer (22). Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing: 40. March 2, 2006. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- ^ Ashburn, Jo (March 1995). "The Making of Full Throttle". Full Throttle Official Player's Guide. Infotainment World Inc. p. 222. ISBN 1-57280-023-2.

- ^ Böke, Ingmar (April 7, 2017). "Tim Schafer – Double Fine: Interview". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Rob (2008). Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-6184-7.

- ^ Goldstein, Hilary (February 3, 2005). "Tim Schafer: A Man and His Beard". Yahoo! Video Games. Archived from the original on February 7, 2008. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ^ Saltzman, Mark (March 15, 2002). "Game Design: Secrets of the Sages -- Creating Characters, Storyboarding, and Design Documents". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ "Chitlins, Whiskey and Skirt". Genius.

- ^ Dutton, Fred (February 10, 2012). "Double Fine Adventure passes Day of the Tentacle budget". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- ^ "75 Power Players". Next Generation (11). Imagine Media: 53. November 1995.

- ^ Staff. "Geniuses at Play; Write the Lightning". Playboy. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007.

- ^ "Latest Software". Daily Record. May 18, 1995. p. 5. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

Full Throttle//CD-ROM//Available Friday

- ^ a b c Makedonski, Brett (March 1, 2017). "In some ways, Tim Schafer's Full Throttle fits in better in 2017 than 1995". Destructoid. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ "Tim Schafer Interview". Edge. August 2009. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ a b "Full Throttle Critic Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ Lauria, Dominick (May 19, 2002). "Full Throttle Review". Adventure Gamers. Archived from the original on October 27, 2002. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c Ardai, Charles (August 1995). "Hawg Heaven". Computer Gaming World. p. 80.

- ^ a b c Adam, Jeffrey (May 1, 1996). "Full Throttle Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Full Throttle". Next Generation (12). Imagine Media: 195. December 1995.

- ^ a b c d e Poole, Steve (August 1995). "Full Throttle review". PC Gamer. p. 80.

- ^ a b c Yee, Bernard H. (November 21, 1998). "Spotlight on Adventure - Full Throttle". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on April 17, 2001. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Negrino, Tom (January 1996). "Full Throttle review". Macworld. Archived from the original on February 6, 1997. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ LeVitus, Bob (March 1996). "The Game Room". MacUser. Archived from the original on February 21, 2001. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ a b Raymo, Rick (August 1995). "Full Throttle". PC Games. Archived from the original on October 18, 1996. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Ratliff, Marshall; Jong, Philip (August 26, 2008). "The rise and fall of Full Throttle: a conversation with Bill Tiller". Adventure Classing Gaming. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- ^ Staff (June 1996). "The Computer Gaming World 1996 Premier Awards". Computer Gaming World. No. 143. pp. 55, 56, 58, 60, 62, 64, 66, 67.

- ^ Editors of PC Gamer (March 1996). "The Year's Best Games". PC Gamer US. 3 (3): 64, 65, 67, 68, 71, 73–75.

- ^ Staff (April 1996). "CGR's Year in Review". Computer Game Review. Archived from the original on October 18, 1996. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ Myslewski, Rik (March 1996). "The Eleventh Annual Editors' Choice Awards". MacUser. 12 (3): 85–91.

- ^ Tiller, Bill (July 4, 2006). "Interview with Bill Tiller - A Vampyre Story". Adventure Advocate (Interview). Interviewed by Ellesar; Fallen_Angel; qrious. Archived from the original on July 12, 2006. Retrieved July 6, 2006.

- ^ "The Empire Strikes Out – LucasArts And The Death Of Adventure Games - gamesTM - Official Website". April 8, 2010. Archived from the original on April 10, 2010.

- ^ "Full Throttle: Hell on Wheels E3 2003 trailer". LucasArts. May 14, 2003. Archived from the original on April 6, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^ "Roy Conrad". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ^ "RIP LucasArts: Disney Shutters Games Development At Iconic Studio". The Huffington Post. April 4, 2013. Archived from the original on April 27, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ "Full Throttle Remastered". Playstation Store. Sony. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ Bonham, Jason (September 25, 2017). "Full Throttle Remastered PS4/Vita Review". EIP Gaming. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ Buckley, Sean (March 14, 2017). "'Full Throttle Remastered' will tear up the road this April". Engadget. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ Bishop, Sam (October 13, 2016). "Full Throttle team reunite to record commentary for remaster". Gamereactor. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^ "Full Throttle Remastered coming to PS4, Vita and PC in 2017". Eurogamer. May 2, 2015. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ^ D'Orazio, Dante (December 5, 2015). "LucasArts classic Full Throttle is getting remastered on PS4 and PS Vita". The Verge. Archived from the original on December 6, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ Tach, Dave (December 5, 2015). "Full Throttle Remastered announced, coming to PS4 and Vita (update)". Polygon. Archived from the original on December 7, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (December 2, 2016). "Here's our first look at Full Throttle Remastered". Polygon. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ Buckley, Sean (March 3, 2017). "Why Tim Schafer keeps remaking his classic games". Engadget. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Makedonski, Brett (May 13, 2020). "Grim Fandango, Full Throttle, and Day of the Tentacle finally break PS4 console exclusivity this year". Destructoid. Retrieved May 13, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kelly, Andy (January 13, 2021). "Warcraft director Duncan Jones wrote an entire script for a Full Throttle movie, and you can read it here". PC Gamer. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ Chalk, Andy (January 10, 2022). "Duncan Jones wants to make a Full Throttle movie, and he needs your help". PC Gamer. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The remastered version was developed and published by Double Fine Productions.

- ^ This would appear to contradict the song "Increased Chances," played during the game, which contains the lines "The population is greatly decreased […] I thank the Lord each day for the apocalypse. / Folks are mostly disfigured or dead […] My mama's face has dripped down into the dirt."[11]

External links

[edit]- 1995 video games

- Adventure games

- DOS games

- IOS games

- Linux games

- LucasArts games

- Classic Mac OS games

- MacOS games

- Motorcycle video games

- PlayStation 4 games

- PlayStation Network games

- PlayStation Vita games

- Point-and-click adventure games

- ScummVM-supported games

- SCUMM games

- Video games scored by Peter McConnell

- Video games developed in the United States

- PlayStation 4 Pro enhanced games

- Single-player video games

- Windows games

- Xbox One games