French anti-Southern sentiment during the Third Republic

French anti-Southern sentiment during the Third Republic manifested as a form of hatred directed towards the French from the South of France. This phenomenon was particularly prevalent at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. This sentiment originated from a multitude of factors, including linguistic, economic, cultural, and historical interpretations of the country and the process of constructing ethnotypes. In this context, the populations of the South were perceived as talkative, vain, and indolent, largely due to the assumption that their lives were easier due to the sunny climate and that they were governed by passions rather than reason. Those with anti-Southern sentiments attributed the preponderance of the South in society to the Roman conquest, the actions of Joan of Arc, and the French Revolution.

A subset of the nationalist right espoused a sentiment of patriotism towards individuals hailing from the South. The patriotism of the Southerners was called into question; they were judged as cowardly and indifferent. Following the defeat in the Battle of Lorraine in 1914, they were hastily declared guilty. Southern politicians, with Léon Gambetta and Ernest Constans at the vanguard, were accused of seizing power through populism to monopolize the wealth of the North and redistribute it in the South. Ultimately, Southerners were portrayed as belonging to a "race" that had been corrupted by Protestants and, in particular, Jews, with whom they were believed to have conspired to seize power. Their general behavior was thought to be a consequence of the structure of their brains.

The origins of the hatred

[edit]From the theory of climates to stigmatizing representations

[edit]The South of France is a geographical area with vague boundaries. It was invented after the Revolution that ended the provinces and is based on a geographical reading of the nation from its Parisian center.[Pi 1][Li 1] Anti-Southern sentiment has its origin in the process of constructing ethnotypes, a moral and physical classification of individuals based on prejudices. These are notably built on the theory of climates,[Pi 2] but also rest on linguistic, economic, cultural, and historical interpretations of the country.[Li 2]

The notion that Southerners are morally and militarily inferior to Northerners due to the climate is a concept that has been expressed by several prominent thinkers throughout history. Montesquieu, in his 1748 work The Spirit of Law, Germaine de Staël in her 1800 treatise On Literature, and Charles Victor de Bonstetten, in his late 18th-century work The Man of the South and the Man of the North or the Influence of Climate, published in 1824, are among the most notable proponents of this idea.[Li 3] In his work, which systematizes this distinction, Bonstetten reflects a mindset that was common at the time.[Li 3]

From the outset of the 19th century, public opinion became increasingly attuned to the economic disparity between the South of France, which remained predominantly agrarian due to a dearth of capital, and the North, which was undergoing industrialization,[Li 4][Pi 3] emulating the growth patterns observed in Britain and Germany.[Li 3] Additionally, the South was perceived (erroneously) to have a lower level of education.[Li 4] Moreover, historical events contributed to constructing a violent image of the Southerners.[Li 5] These events included the massacres at La Glacière in Avignon in 1791, the decisive intervention of the Marseillais on August 10, 1792, the Federalist insurrection of 1793, and the violence of the White Terror in 1815.[Li 5]

The ethnotypic view of the South of France as a uniform space was pervasive in literature and popular culture.[Pi 3] The populations of the region were often depicted as loquacious, vain, and indolent, due to the assumption that life was easy for them due to the sunny climate. They were also portrayed as governed by passions rather than reason, and thus violent.[Pi 4][Ca 1][Ma 1] Additionally, their accent, the use of Occitan, which was incomprehensible to Northerners, and their way of speaking French were also mocked.[Ma 2][Li 4]

At the turn of the Second Empire and the Third Republic, in the popular Northern mindset, the Provençal was perceived as the embodiment of the Southerner, replacing the Gascon, which had previously been regarded as the epitome of the region's characteristics. The Provençal was now seen as "boastful and ridiculous," while the Gascon was considered "verbose and boastful but proud and quarrelsome." In the early 1870s, the success of Tartarin of Tarascon by Alphonse Daudet significantly contributed to this movement.[Pi 5] Furthermore, these stigmatizing representations were repeated in school textbooks and novels in the second half of the 19th century,[Pi 6] which reinforced the North/South opposition among the elites,[Pi 7] including Ernest Renan, the leading thinker of French intellectuals.[Li 6]

The origins seen by anti-Southerners

[edit]

Some historians who were critical of the South sought to identify the historical origins of what they perceived to be an ethnic disparity.[Se 1] In an article published in Le Gaulois in 1903, Maurice Barrès posited that the conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar was the primary cause of the disparity between the North and the South.[Se 2] In his thesis novel, Jean Révolte, roman de lutte (1892), Gaston Méry posits that ancient Rome served as a bridgehead for Southern expansion towards Northern Europe.[Se 3] For some conservatives, the 1789 Revolution unfortunately granted primacy to the Gallo-Roman stock of the South, inclined towards egalitarianism, pacifism, and pleasure, over the Frankish stock of the North, inclined towards elitism, militarism, and work.[Pi 8][Se 4] This was posited as the cause of the defeat of 1870 by Ernest Renan.[Pi 8]

In his 1891 novel Là-bas, Joris-Karl Huysmans posited a prehistoric scenario in which the English Channel had not yet formed and France and England constituted a unified territory and population.[Se 2] It was believed that Joan of Arc was the cause of this incoherent France, incorrectly uniting the incompatibilities of the South and the North.[Se 5] In a pamphlet published the following year, the Freemason Louis Martin, a progressive republican, put forth the argument that she had prevented the fusion of two sister nations and led to the exacerbation of French and English national characteristics.[Se 5] Conversely, for Charles Maurras, a staunch defender of the South despite his nationalist leanings, she repelled the Northern enemy and preserved Latin predominance.[Se 5]

As Joris-Karl Huysmans observed, the Renaissance, with its return to antiquity, also had an impact on Northern Gothic literature. This impact manifested in the infusion of Mediterranean paganism into the literary landscape. One notable example is the replacement of the Virgin Mary with the Venus figure.[Se 6]

The nature of the hatred

[edit]Anti-Southern sentiment, in varying degrees of intensity and focus, manifested as disdain, mistrust, hostility,[Li 7] hatred, or racism and was a prevalent phenomenon between 1870 and 1914.[Ca 2][Pi 9] Robert Lafont discussed the phenomenon of internal racism,[Li 8] which he identified as a product of the enduring tensions within French society.[Ma 3] By the early 1890s, as Jean-Marie Seillan observed, these tensions had reached a point where they gave rise to a form of proto-fascism in France.[Se 7] Three key factors were identified as the primary drivers of the most vehement anti-Southern sentiment.

Patriotism and military engagement

[edit]

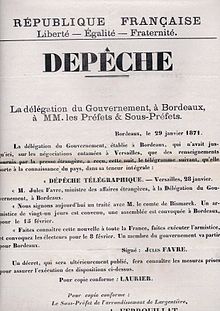

The regions of the South exhibited a persistent aversion to the French state, which manifested in various forms of resistance, including reluctance to fulfill military obligations, evasion of taxation, and, on occasion, violent revolt.[Pi 7] However, the defeat of 1870 left a profound impact, and individuals were sought to bear the brunt of the collective blame.[Pi 10] In his 1871 work La Défense de Tarascon, Alphonse Daudet portrayed Southerners as both boastful and indifferent to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.[Pi 10][Li 9] The generalization of Tarasconians to all Southerners was swiftly embraced in the context of the profound disappointment and resentment that accompanied the defeat.[Pi 11] In his work De Profundis, a piece from his Songs of the Soldier, the poet Paul Déroulède portrays a Marseillais who chooses to maintain his tranquility rather than engage in combat. The text of this collection, which had a significant audience until 1914, significantly influenced the perception of Southerners as cowardly and unpatriotic.[Pi 11][Li 9] However, a comparative study of war efforts by French departments demonstrated no notable differences, and post-armistice mutinies also occurred in both the South and North of France.[Li 9]

The 1907 winegrowers' revolt was distinguished by the mutiny of a portion of the 17th Infantry Regiment, comprising Southern soldiers, who were concerned about the fate of the inhabitants of Béziers. The military authority, in a scathing report, relied on stigmatizing ethnotypical fantasies to a significant extent.[Li 6] Lieutenant-Colonel Émile Driant echoed these in his novel Robinsons sous-marins, which was very popular among conservative youth. The novel is built on an opposition between a devoted Breton and a repulsive, hateful, rebellious, and "internationalist" Provençal.[Li 6]

Following the French army's initial setback in August 1914, during the Battle of Lorraine, Parisian senator Auguste Gervais, in an article published in Le Matin, as well as several other newspapers, attributed the defeat to the Provençals of the 15th Corps. However, historical analysis has shown that the defeat resulted from the inadequacy of the campaign plan and the doctrine of an all-out offensive.[Pi 12] Two soldiers were executed in violation of the law.[Ma 4] Notwithstanding the government's denials, the affair had a detrimental impact on the reputation of Southerners.[1] On the front, Southern soldiers were held in low regard, perceived as cowardly, and subjected to harassment by soldiers and officers from the North.[1][Pi 13] The appellation "Tartarin," for instance, was employed as an epithet directed at Southern combatants.[Li 10] In the context of the extensive demographic integration that the war engendered, the invocation of stereotypes imbued one's environment with meaning and reinforced one's sense of identity.[Pi 14] In the face of pervasive prejudices, Southern soldiers from a particular region might attempt to deflect blame onto those from an alternative region within the South or disavow their affiliation with the South.[Pi 15]

Southerners in control of the State

[edit]The nationalist, conservative right, excluded from power by the Republicans, rapidly accepted the premise that Southern politicians, predominantly from the left, had assumed control to consolidate the wealth of the North, redistribute it in the South, and secure allegiance.[Pi 16][Ca 3] Between 1871 and 1914, only 28.3% of ministerial and state secretary positions were held by people from the South.[2] Despite this, the South was perceived as economically lagging,[Pi 17] while the North, which was much more industrialized, contributed significantly to the state budget.[Ma 5] Additionally, the Southerner was considered inclined towards radicalism and socialism due to social conflicts or political expressions.[Pi 11][Li 11]

The proliferation of hateful fantasies can be attributed, at least in part, to the influence of literary elites.[Pi 18] Notable proponents of this perspective include Joris-Karl Huysmans, and Gaston Méry, who wrote in Jean Révolte, Roman de lutte (1892), "The Southerner, that's the enemy!," Léon Daudet, and several newspapers such as Le Matin and La Gazette.[Pi 16] In an article published in Le Figaro in 1871, Alphonse Daudet, an anti-republican, accused Southerners of exploiting the war to engage in politics and being responsible for establishing the Third Republic.[Pi 19] In Victorien Sardou's 1872 play Rabagas, the Provençals are depicted as having seized control of the state. Similarly, in Alphonse Daudet's 1881 novel Numa Roumestan, they are portrayed as eloquent talkers with little taste for action, who prefer to seize power through parliamentarism. This novel was successfully adapted for the theater in Paris.[Pi 18][Li 10] The figure of Léon Gambetta is central to both cases.[Pi 18] The sociologist Edmond Demolins, in Les Français d'aujourd'hui (1898), attempts to identify the underlying causes of this phenomenon by examining the role of subsistence and climate. As summarized by historian Céline Piot, the sentiment is hardly complimentary: "The Southerners are victims of an incurable inability to work, and thus naturally inclined towards politics, which is a profitable industry for lazy and non-industrious peoples."[Pi 20]

The prominent role of Ernest Constans from Béziers, minister of the interior, in the expulsion of religious congregations and opposition to General Georges Boulanger and the Ligue des patriotes, incited another surge of animosity from the far-right.[Ca 4][Li 8] Similarly, the ascendance of the Bloc des gauches between 1902 and 1904, which included numerous Southerners and pursued an assertive anti-clerical policy, incited resentment.[Ca 4][Li 8] Southerners were perceived as undermining the authority of the Church through their promotion of secularization and their association with the tarnishing of the honor of the army in the Dreyfus Affair.[Ca 3][Pi 21] Deputies such as Jules Delafosse, writers including Jules Lemaître, president of the Ligue de la patrie française, Maurice Barrès, and others were eager to condemn the dominance and ineptitude of Southern political figures, which they believed undermined the influence of Northern leaders.[Ca 5][Li 8] In 1907, Charles Maurras, a nationalist from the South who opposed leftist radicals, asserted that Southern politicians were intentionally maintaining the country in a state of subjugation.[Pi 16]

In the aftermath of the First World War, the incursion of Southern officials into the Northern and Eastern regions was met with considerable resistance. The invasion itself was denounced, as were the presumed inefficiency and lack of legitimacy of the officials who had invaded.[Ma 6]

Southerners tainted by other races

[edit]Many authors, including Arthur de Gobineau, Jules Michelet, and Hippolyte Taine, conceptualized Southerners as a distinct racial group.[Li 8] Gobineau viewed populations south of the Seine as in a state of decline, comprising only vestiges of the Germanic race.[Li 8] Michelet characterized them as a heterogeneous, troubled, anxious, and turbulent population.[Li 12] On the other hand, Taine depicted them as sensual, quick-tempered, rough, and lacking in intellectual and moral fortitude.[Li 12]

From the perspective of some nationalists, Southerners were perceived as anti-French and as being at odds with the nation's interests. This was attributed to their belonging to a different racial group, or more specifically, to their having been influenced by foreign ideas and blood.[Pi 22] It is alleged that the South was home to the largest concentrations of Protestants and, in particular, Jews.[Pi 22] The concept of Jewish influence in the South can be traced back to Arthur de Gobineau's 1852 essay, L'Essai sur l'inégalité des races. However, the explicit association of Southerners with Jews emerged during the rise of the Third Republic and the subsequent fear of democracy.[Pi 22] For Provençal Charles Maurras, the Southern population remained healthy in its internal exile, and its missteps were due only to Jewish, Protestant, or Albigensian oppression.[Ca 6][Pi 23] However, Maurras was virtually alone in promoting this view.

Similarly, Southerners, who may have exhibited physical characteristics analogous to those of Jews,[Ca 7] were purported to be readily identifiable by a distinctive accent, mannerisms, and even the odor of garlic they exuded.[Pi 24] The language itself was regarded as superficial.[Ca 8] Some scientists lent support to the notion of racial distinctions. In 1911, in the journal L'Opinion, Dr. Répin from the Pasteur Institute posited that the observed opposition between the temperaments of dolichocephalic races (Northern men, such as the Anglo-Saxons or the Franks) and those of brachycephalic races (Southern men, such as the Latins and Celts) was due to brain size. It was postulated that Southern brains were smaller and therefore less inclined to reflection. However, the frequency of neural connections was held to explain their talkativeness and ease of speech.[Pi 25]

In volume II of La France juive (1886), Édouard Drumont asserted that Léon Gambetta sought to establish a Jewish Republic in France.[Pi 21] In a similar vein, Gaston Méry, an admirer of Drumont, posited that the Southerners and the Jews were like brothers and that they were interdependent. "The first requires the second's financial resources to secure electoral victory, while the second can more effectively consolidate its position if it can advance while concealed by the first." Consequently, Méry postulated the existence of two distinct threats: the Latin peril and the Jewish peril.[Pi 21] However, he was distinctive in his assertion that the Germans had constituted the nobility vanquished by the Revolution, that the Latins constituted the majority of the bourgeoisie that needed to be subdued, and that the Celts, with their purported pure bloodline, constituted the people who must rise.[Se 8]

As posited by literary historian Sarah Al-Matary, the Boulangist experience inaugurates novelistic aesthetic perspectives that assume the form of "racial" literature, politicized and occasionally in dialogue with "scholarly production" that, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, purported to discern an autocratic proclivity among Latin peoples, manifesting in forms such as absolute monarchy, the Terror, and Caesarism.[AM 1] Some idealized the "Latin race" as a model of civilization, while those on the opposite end of the political spectrum exhibited sentiments of disgust or hatred.[AM 2][Se 9]

A gradual mitigation

[edit]Following the conclusion of World War I, French anti-Southern sentiment exhibited a gradual decline, particularly due to population shifts.[Li 7] However, in 1935, Alexis Carrel, a Nobel laureate, still espoused the view that Northern races were superior to those on the Mediterranean coasts.[Li 7] Before World War II, the writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline, whose works evince a "Nordicism," explicitly manifested his anti-Southern sentiments by reusing several clichés. These included portraying the North as a conquering and productive entity, in contrast to the South as a threatening and paralyzing force.[AM 3] In L'École des cadavres, Sarah Al-Matary notes that the author equates "Latinism" with "Greece," which is "already of the Orient." This invokes Freemasonry, which the pamphleteer associates with "Jews," frequently compared in his writings to "Negroes."[AM 4]

References

[edit]- Al-Matary, Sarah (2017). "Des rayons et des ombres. Latinité, littérature et réaction en France (1880–1940)". Cahiers de la Méditerranée (in French) (95): 15–29. doi:10.4000/cdlm.8812. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021.

- ^ Al-Matary 2017, par. 12

- ^ Al-Matary 2017, par. 12-27

- ^ Al-Matary 2017, par. 28-30

- ^ Al-Matary 2017, par. 29

- Cabanel, Patrick; Vallez, Maryline (2005). "La haine du Midi: l'antiméridionalisme dans la France de la Belle Époque". Actes des congrès nationaux des sociétés historiques et scientifiques, 2001. Vol. 126. Toulouse. Archived from the original on August 23, 2024.

- ^ Cabanel & Vallez 2005, p. 88

- ^ Cabanel & Vallez 2005, p. 87

- ^ a b Cabanel & Vallez 2005, pp. 87–88

- ^ a b Cabanel & Vallez 2005, p. 91

- ^ Cabanel & Vallez 2005, pp. 91–93

- ^ Cabanel & Vallez 2005, pp. 94–95

- ^ Cabanel & Vallez 2005, p. 90

- ^ Cabanel & Vallez 2005, p. 89

- Lafon, Alexandre (2012). "Le Midi au front: représentations et sentiment d'appartenance des combattants méridionaux 1914-1918". Le Midi, les Midis dans la IIIe République (Nérac, 13 mai 2011) (in French). Nérac: Éditions d'Albret.

- Liens, George (1977). "Le stéréotype du Méridional vu par les Français du Nord de 1815 à 1914". Provence Historique (in French) (110): 413–431.

- ^ Liens 1977, p. 415

- ^ Liens 1977, pp. 416–417

- ^ a b c Liens 1977, p. 416

- ^ a b c Liens 1977, p. 417

- ^ a b Liens 1977, p. 418

- ^ a b c Liens 1977, p. 429

- ^ a b c Liens 1977, p. 430

- ^ a b c d e f Liens 1977, p. 428

- ^ a b c Liens 1977, pp. 423–424

- ^ a b Liens 1977, p. 425

- ^ Liens 1977, pp. 426–427

- ^ a b Liens 1977, pp. 419–420

- Marcilloux, Patrice (2005). "L'anti-Nord ou le péril méridional". Revue du Nord (in French) (360–361): 647–672. doi:10.3917/rdn.360.0647. Archived from the original on September 11, 2018.

- ^ Marcilloux 2005, par. 5-7

- ^ Marcilloux 2005, par. 5

- ^ Marcilloux 2005, par. 49

- ^ Marcilloux 2005, par. 3

- ^ Marcilloux 2005, par. 10-11

- ^ Marcilloux 2005, par. 35-41

- Piot, Céline (2017). "La fabrique de l'autre: l'anti-méridionalité au XIXe siècle". Klesis (in French) (38): 45–73. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 5, 2021.

- ^ Piot 2017, pp. 46, 53

- ^ Piot 2017, p. 48

- ^ a b Piot 2017, p. 50

- ^ Piot 2017, pp. 48–49

- ^ Piot 2017, pp. 53–54

- ^ Piot 2017, p. 52

- ^ a b Piot 2017, pp. 50–51

- ^ a b Piot 2017, pp. 61–62

- ^ Piot 2017, pp. 58–59

- ^ a b Piot 2017, p. 54

- ^ a b c Piot 2017, p. 55

- ^ Piot 2017, pp. 56, 62

- ^ Piot 2017, pp. 65–66

- ^ Piot 2017, p. 70

- ^ Piot 2017, pp. 67–68

- ^ a b c Piot 2017, pp. 56–57

- ^ Piot 2017, pp. 49–50

- ^ a b c Piot 2017, pp. 57–58

- ^ Piot 2017, pp. 54–55

- ^ Piot 2017, p. 58

- ^ a b c Piot 2017, pp. 60–61

- ^ a b c Piot 2017, p. 60

- ^ Piot 2017, pp. 52–53

- ^ Piot 2017, p. 61

- ^ Piot 2017, p. 69

- Seillan, Jean-Marie (2003). "Nord contre Sud. Visages de l'antiméridionalisme dans la littérature française de la fin du XIXe siècle". Loxias (in French). 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018.

- ^ Seillan 2003, par. 18

- ^ a b Seillan 2003, par. 30

- ^ Seillan 2003, par. 36

- ^ Seillan 2003, par. 21

- ^ a b c Seillan 2003, par. 22-29

- ^ Seillan 2003, par. 20

- ^ Seillan 2003, par. 42

- ^ Seillan 2003, par. 34-39

- ^ Seillan 2003, par. 5-17, 42

- Other references

- ^ a b Le Naour, Jean-Yves (2000). "La faute aux "Midis": la légende de la lâcheté des Méridionaux au feu". Annales du Midi: Revue archéologique, historique et philologique de la France méridionale (in French). 112 (232): 499–516. doi:10.3406/anami.2000.2682. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023.

- ^ Estèbe, Jean (1976). "La République a-t-elle été gouvernée par le Midi de 1871 à 1914 ?". France du Nord et France du Midi, Actes du 96e congrès des sociétés savantes, 1971 (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: CTHS. pp. 189–196.