Trams in Freiburg im Breisgau

| Freiburg im Breisgau tramway network | |||

|---|---|---|---|

A Landwasser bound tram in Freiburg | |||

| Operation | |||

| Locale | Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany | ||

| Open | 14 October 1901 | ||

| Status | Operational | ||

| Lines | 5 | ||

| Operator(s) | Freiburger Verkehrs AG | ||

| Infrastructure | |||

| Track gauge | 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) metre gauge | ||

| Propulsion system(s) | Electricity | ||

| Electrification | 750 V DC | ||

| Depot(s) | 1 (Betriebshof West) | ||

| Stock | 73 trams | ||

| Statistics | |||

| Route length | 32.3 km (20.1 mi)[citation needed] | ||

| Stops | 73 | ||

| |||

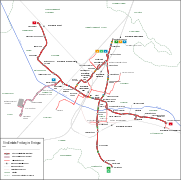

The Freiburg im Breisgau tramway network (also known as Stadtbahn or formerly as Hoobl (Alemannic for Hobel))[1] is a network of tramways that forms part of the public transport system in Freiburg im Breisgau, a city in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Established in 1901, the network has been operated since its foundation by the company now known as Freiburger Verkehrs (VAG Freiburg or VAG), and powered by electricity. The tramway network currently has five lines. The expansion of the tram network since 1980 has served as an example of the "renaissance of the trams" in Germany. As of 2023, 73 trams were available for regular use: 2 of these were high-floored, 36 partial and 35 low-floored.[2][3] Almost the entirety of the network is located within Freiburg's urban area; only a few metres of the balloon loop at Gundelfinger Straße are located outside the boundary of Gundelfingen to the north of Freiburg. In total, the trams serve 20 out of the 28 districts in Freiburg.

History

[edit]Time before trams

[edit]After Freiburg was connected to the railway network via the Rhine Valley railway from 1845, there was an intercity transport link between the Hauptbahnhof and the Wiehre Train Station, which used the Hell Valley Railway for the first time in 1887. From 1891, horse-drawn buses, operated by two different private companies, transported citizens throughout the town. The horse-drawn buses were used on three lines: Lorettostraße to Rennweg, Waldsee to Hauptbahnhof, and Siegesdenkmal to Horben. They were eventually replaced by trams, except between Günterstal and Bohrer.[4]

In May 1899, the city council made the decision to build an electric transport system in Stühlinger. Reasons for it included the University of Freiburg's increasing requirement for light and power, and the planned refurbishment of the town's trams. An 1899 survey by the city council resulted in a power requirement for more than 20,000 incandescent lamps.

The acting mayor at the time, Otto Winterer, decisively ensured the fast implementation of the trams. The concession for powering the tram was safeguarded by Direktion des Elektrizitätswerkes und der Straßenbahn, the name of the former VAG company. The tasks of building electric centre for producing light and power and the tramway were assigned to Siemens & Halske from Berlin. Because the supply of hydropower in the environment was too low, the decision was made to generate electricity via a steam power plant.

The tram's planners considered Freiburg Bächle in the Old City to be problematic, since it was feared that the trams could fall into the Bächle in the event of a derailment. It also had to be ensured that the entrances on the Bächle side remained closed. In the end, a senior engineer from the Hamburg trams project, "could not recommend the building of platforms next to the Bächle under any circumstances" and recommended that the Bächle be covered, which was ignored in order to preserve the Bächle as a landmark of Freiburg.[5]

Not included in the construction contract were the conversion and restoration of the streets after laying the tracks and erecting the depot at Urachstraße; this work was undertaken by the city and municipal building authorities. At the same time as the tram network, Freiburg had access to electric road lighting that was powered by the same electricity plant, which still exists today, and is located on Eschholzstraße, away from the tram network.[1] From there, a subterranean supply led to the corner of Betheroldstraße and Wilhelmstraße and another to the square in front of the Johanneskirche.

Initial operation

[edit]On 30 August 1901, the first test run took place,[6] with the first public-serving trams operating in the autumn. From 14 October 1901 onwards, lines A and D went into operation before lines B and C, which opened on 2 December 1901. The original length was nine kilometres and had 34 stops. The latter two routes were only able to operate once the Schwabentor had been converted. For the two-tracked tramway, it was extended, like the Martinstor, with a second passageway.[7] At first, however, the lines were only used for internal purposes and were not prescribed to trams. Freiburg was the fourth tram network installed within the Grand Duchy of Baden. In contrast to the older networks in Heidelberg, Karlsruhe, and Mannheim, which were all supplied with electricity three months before the plant opened in Freiburg, trams in the Breisgau were powered by electricity from the outset and used lyric current collectors.

The power plant opened on 1 October 1901 and regularly produced direct current. In the first year, 61 percent of the 177,000 Kilowatt hours were used by the tram network until 1933, when it received its own supply. In the beginning, the network ran as follows:

| Line | Route | Cycle | Journey time | Turnaround time | Courses | Stops |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Rennweg-Lorettostraße | Every 10 minutes (7 am and 9 am) Every 5 minutes |

14 minutes | 40 minutes (7 am and 9 am) Every 35 minutes |

4 / 7 | 16 |

| B | Hauptbahnhof-Lorettostraße | every 10 minutes | 13 minutes | 40 minutes | 4 | 11 |

| C | Hauptbahnhof-Bleicheweg | every 10 minutes | 12 minutes | 30 minutes | 3 | 10 |

| D | Rennweg-Günterstal | Every 15 minutes | 23 minutes | 60 minutes | 4 | 21 |

Lines A and D ran along Habsburger Straße, Kaiser-Joseph-Straße, and Günterstalstraße, while the section Line D alone served encompassed the entire length of Schauninslandstraße. Lines B and C both followed Bismarckallee, Bertoldstraße, Salzstraße, Straße Oberlinden and the Schwabentorring until its southern end. From there, only Line B served Hildastraße and Urachstraße, while Line C followed Schwarzwaldstraße to the east. For train crossings, seven were accessible on the single-track east–west route.

During the morning peak, up to 18 trams were used simultaneously, while nine others were in reserve. In the inner city, a denser supply resulted from the superposition of Lines A and D. There was on the single double-track railway of the network between Rennweg, now Hauptstraße, and Lorettostraße up to 16 trips per hour. On the interchange Lorettostraße-Günterstal, which was originally cross-bordered, the only intermediate passing loop was at Wonnhalde. The line to Güterstal, as a single line at the time, was operated by a trailer car, which was why there was a transfer line at the two terminals of Rennweg and Günterstal. There were four open summer carriages available for the strong holiday traffic during this season. The section serving Hauptbahnhof and Schwabentorbrücke was served by twelve cars an hour. However, due to the single-track infrastructure, the trams on lines B and C always ran very close behind each other.

An operational feature from the earlier years was the level junction at Günterstalstraße (a few metres south of Lorettostraße and Urachstraße) for the interurban route to Günterstal with Höllentalbahn, which had not yet been powered.

Since 1902, the tram transported more than three million passengers, while the horse-drawn bus lines in their last full year of operation in 1900 only transported 50,000 passengers. In the same years, Lines B and C were extended from their former endpoint at the Hauptbahnhof by approximately 200 metres to the northwest at Lehener Straße.[8] Heading towards Lehener Straße, trams were still signposted for the Hauptbahnhof.

Within the inner city, the operating company introduced a uniform tariff of ten pfennigs in 1902, and it was the only reason for a one-off transfer to Bertoldsbrunnen junction (colloquially called Fischbrunnen, or Fish's Well), Schwabentorbrücke and Lorettostraße. The fee for the route from Günterstal to Lorettostraße was ten pfennigs. It also cost 20 pfennigs for trips beyond Lorettostraße.

First extensions

[edit]

The 15-minute trip to Günterstal was inadequate for the high demand on this service, so the operating company installed two additional passing points at Waldhüterhaus on Schauinslandstraße and at Günterstaler Kreuz, which reduced the trip time to 10 minutes. In order to further increase capacity on this route, three more summer trams were put into operation in the same year, and the first extensions were installed. At the beginning of the summer schedule in 1905, Alter Messplatz, also called Bleicheweg, was added to the loop at Stadthalle—the first terminal loop in Freiburg. The terminus station was Waldsee, named after the waters in the recreation area of Möslepark.

In the following year, lines B and C were expanded into two-track lines, except for the short single-track section between Bleicheweg and Waldsee.

In 1908, both of the newly constructed stretch of tracks between Hauptstraße and Okenstraße, and Lehener Straße to Güterbahnhof became operational. The latter was located on Breisacher Straße and Hugstetter Straße to Hohenzollernplatz (now Friedrich-Ebert-Platz). The route followed along the course of Heiliggeiststraße and Friedhofstraße to the terminating station of Güterbahnhof on the corner of Waldkircher Straße/Eichstätter Straße. The route was designed to be double-tracked right for five-minute cycles.

Further extensions after 1909

[edit]When the new bridge from Siegesdenkmal via Friedrichring, Friedrichstraße, and Hauptbahnhof to Stühlinger was commissioned, a fifth line was introduced in 1909 using Arabic numbers. The new Line 5 operated on a ten-minute cycle and used the "Blue Bridge" to cross the main railway line.[10] In Stühlinger, the terminal loop was built around the Herz-Jesu church. Further destinations included the districts of Haslach, Herdern, and Zähringen, as well as a short extension in Wiehre:

- 1910: Lorettostraße - Goethestraße and, after completion of the new railway underpass Komturbrücke, Rossgässle (today Okenstraße) - Reutebachgasse

- 1913: Stühlinger Kirchplatz (today Eschholzstraße) - Scherrerplatz

- 1914: Siegesdenkmal - Immentalstraße

Zähringen had only belonged to Freiburg from 1906, the tram connection was part of the Merger treaty.[11] The route through Herdern forced the introduction of a sixth line.

Four other stretches of track were planned, but they could not be implemented because of World War I. A line was planned to connect Johanneskirche and Reiterstraße, another between Stühlinger Kirchplatz and Hohenzollernplatz via Eschholzstraße, and one more from the Betzenhausen and Mooswald districts.[12]

An overland stretch from Günterstal via Horben and Schauinsland to Todtnau was planned,[12] where the route was going to connect a metre gauge train line to Zell im Wiesental. The planners had hoped for a quick connection to the tourist-friendly southern Black Forest.

World War I

[edit]During World War I, most of the workforce was conscripted for military service. Of the original 133 employees, only eight remained. As a result, women were employed for the first time by the Armed Forces from 1915.[13]

After the war started, the tram network was used to transport the wounded to numerous lazarettos across the city. As a result, a new railway connection was constructed from Zollhallenplatz, through Neunlindenstraée and Rampenstraße to the remote military section of the freight station. Trams for transporting injured people waited for the lazaretto trains at the loading stations. The carriages and sidecarriages were able to transport twelve heavily wounded people.[14] In total, 20,779 injured soldiers were transported. After World War I, the track through Neunlindenstraße served as a shortened form for many years to link the former railway track at Kaiserstuhlstraße.

A connection between the trams and the Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway was built in 1917 in the civilian part of the Güterbahnhof. This track originated from the terminal station, which was located at the mouth of Eichstetter Straße into Waldkircher Straße to Güterbahnhof, in order to enable direct reloading. The company procured ten freight trucks and rebuilt the open summer carts 102–104. The connection existed until the start of the 1980s, when the GT8K motor coaches were delivered to Freiburg via a partially four-lane line.

The company began to expand existing routes into two-track lines. The second track between Wonnhalde and Wiesenweg went into operation on the route towards Günterstal at the end of 1913. In the autumn of 1917, the section followed from Silberbachstraße to Wonnhalde.

During the war, a severe accident occurred immediately after an air attack on the level crossroads at Hellentalbahn. On 12 October 1916, around 9:30 pm, a tram driver travelling into the city did not see the closed barrier at night and collided with a railway train travelling uphill. The driver was severely injured, and the conductor and the only passenger only suffered minor injuries.[15][16]

Period between the World Wars

[edit]

In 1919, the operating company combined Line 5 (Siegesdenkmal – Scherrerplatz) and Line 6 (Siegesdenkmal – Immentalstraße) into the new Line 5 from Scherrerplatz to Immentalstraße. In 1921, there were already six lines when the terminus of Line 3 was moved from Goethestraße to the stop at today's Musikhochschule, and a new Line 6 from Schwabentorbrücke to Goethestraße was introduced. In the same year, lines became colour-coded in order to facilitate passenger orientation.[17]

Because of hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic, daily passenger numbers decreased from 40,000 in 1919 to under 3,000 in 1923. At the same time, the price for a one-way journey increased from 15 pfennigs to 100 billion Reichsmark, and tram rides became unattractive. Line 6 was discontinued on 16 October 1916 and the cycles of the other lines waned. The situation only improved when the Rentenmark was introduced in November 1923. On 22 December 1924, Line 6 was reopened between Schwabentorbrücke and Goethestraße.

In 1925, a further extension went into operation in the suburb of Littenweiler, which had been incorporated in 1914. It was to be opened in the same year as the Merger treaty, and was one of the reasons for the community giving up its independence,[18] but the extension had to be delayed by eleven years because of World War I. At times, an alternative route through the southern-running Waldseestraße was considered. Its course would have led to the centre of Littenweiler, but directly after the loop at Stadthalle, a further crossroads with Höllentalbahn became necessary. After the line was extended to Littenweiler, the garden city of Waldsee, which had only been established after World War I, also profited. It closed the settlement gap between the Wiehre and Littenweiler, and connected with Freiburg's city centre. In the same year, the first motor bus from Freiburg was set up from Hohenzollernplatz to Betzenhausen.

In 1928, the operating company built the last part of the new stretch of track between Rennweg and Komturplatz, where a second depot was opened at the same time. In return, the operation of the short branch line between today's stop at Rennweg and Güterbahnhof was stopped.

After the Schauinslandbahn was opened on 17 July 1930, the tram's directorate applied for a two-track extension between Wiesenweg and Günterstäler Tor on 23 January 1931 to improve the feeder service to the Talstation. The company also planned a new four-kilometre long stretch of track to connect the mountain railway network to the tram network.[19] Die Gesellschaft plante außerdem eine vier Kilometer lange Neubaustrecke zur Anbindung der Bergbahn an das Straßenbahnnetz.[20] At the terminus of Talstation, a terminal loop was built in front of the station building, which forced the side carriages to be suspended in Günterstal, and motor cars had to be operated on their own up to the Talstation. The high costs for the maintenance garage in Günterstal and five additional rail cars led to the decision of using this connection as an alternative to bus routes.

In 1931, the first complete shutdown of a section took place when the route leading to Goethestraße went out of service. Line 6 served between Schwabentorbrück and the Wiehre train station. The section between Wiehre train station and Lorettostraße remained as an operational route to the depot.

From 1933, members of the Sturmabteilung and the Schutzstaffel, as well as members of the Hitler Youth received a tariff reduction by one unit price of ten Reichspfennigs on any route. Jews were forbidden from using public trams.[21]

On 8 November 1934, the facilitation of operations in a southern direction led to a relief for the tram network, and as a result the level crossing was no longer in use. The main railway line crossed the Günterstal section at Holbeinstraße at Sternwaldtunnel. The tram company was also able to complete the two-track expansion of the route to Günterstal by closing the gap between Lorettostraße and Silberbachstraße. The neutralisation of the railway also affected the tram network, because the Wiehre now had access to a new train station on Türkenlouisstraße. At the time, there was no direct connection between Höllentalbahn and Line 6.

From 1938 to 1943, the annual number of passengers doubled to more than ten million passengers as motorised private transport almost stopped as a result of the crude oil crisis. However, no new vehicles could be procured.[22] In order to maintain the network, in the years of 1942 and 1943, 43 of the original 101 stops were closed. After six years of operation, Line 6 was reactivated from 196, and connected Schwabentorbrücke to Lorettostraße. The loop at today's Stadthalle no longer served there from 1938 to 1939 in accordance to the plan, since trams on the reinforced Line 3 stopped at Römerhof.

In 1943, the city council decided to introduce the trolleybus as a third mode of urbanised transport after diesel had become scarce to operate buses.[23] Bus Lines B (Johanesskirche to Haslach Englerplatz) and C (Johanneskirche to St. Georgen) and, optionally, the second tram network had to be changed over to the entire tram network. Construction began with the installation of the first overhead mast on 1 August 1944. As a result of World War II, there were delays to the overhead line material and ordered vehicles. After the war, construction was abandoned.

World War II and Post-War era

[edit]

During the air attack on Freiburg on 27 November 1944, several vehicles and half of the overhead network were destroyed.[24] At the time of the attack, there were around 30 vehicles in evening traffic in service. Rail car 1 was destroyed at the railway depot, car 7 by detonations in the Nord depot, and two sets of carriages from vehicle 53 and the side carriage of 110 in front of the City Theatre. Carriage 44 and side carriage 107 were hit at Bismarckallee. 26 other vehicles were badly damaged by the bombs.

From 15 April 1945, all trams stopped operations as the electrical crossing had been destroyed during the war. On 26 May 1945, the operating company resumed the Holzmarkt-Günterstal and Oberlinden-Littenweiler routes after repairing the tracks and overpass on the slightly damaged sections of the route. After a temporary bridge had been erected for the Rheintalbahn at Komturplaty, the entire Zähringen-Günterstal route was operational for lines 1 and 2 again from 4 October 1945. Line 5 was interrupted by a bombing on the Blue Bridge until 1948. On 1 September 1946, a shuttle service was established.

Reconstruction plans included numerous varieties of trams. Ultimately, the original routes were maintained to preserve the accessibility and importance to the city centre. A changeover to trolleybus operation was criticised by planners after it failed to start during the Second World War.[25]

The trolley bus operation in a densely built city centre can never reach the performance of a railroad

— Planner of the City's Tram Network, 1953

In 1950, the connection between Schwabentorbrücke and Lorettostraße lost its line traffic, but remained as an operational route to the depot until 1959.[26] Line 5 experienced a further 300 m extension from Immentalstraße to St. Urban church.[27] A further extension at Richard-Wagner-Straße and Hinterkirchstraße to Zähringen could not be implemented.

Until 1959, additional trams were provided after evening shows at Theater Freiburg. They travelled from the tri-track station in Bertoldstraße to the Wiehre, Zähringen and Günterstal.[28]

Unidirectional operation and closure of Line 5

[edit]

The lack of managers and desire to save jobs led to the commissioning of the so-called "Sputnik trams", which were named after the first artificial earth satellite in 1957. They had the same capacity as a two-axle carriage and side carriage, but could be handled by one conductor using a one-way embarking and disembarking system. They were also the first Freiburg uni-directional vehicles but could only be used on Line 4. A provisional triangular junction had been set up at the terminus station at Littenweiler. They had already been using the turning loop started in 1954 at the other end of the commuter station. Another novelty of the early 1950s were the three-car coaches, which consisted of a motor coach and two side carriages.

At the end of 1961, the operating company closed Line 5 for "economic and traffic reasons", and replaced it with the then bus line H. The reason for the decommissioning was, among other things, the poor introduction into the traffic area. A conversion to a more efficient route with its own railway body was therefore not possible. In addition, modern traction units could not be used on the curvy track. Thus, as in the early days, there were only four lines.

In order to spare the cumbersome marshalling operation at the triangular junction of line 4, the VAG installed a turning loop at Littenweiler due to the lack of space at Lassbergstraße, which meant that Littenweiler lost its tram connection. In the district of Brühl at the other end of the line, a new block of flats was opened on 20 December 1962[29] at Offenburgstraße and Hornusstraße. The old loop at Komturplatz became a hindrance to traffic because of the cramped situation.[30]

By shortening the track in Littenweiler, the network shrank by almost 30 percent within a few years: from 19.7 kilometres in 1945 to 14.2 kilometres in July 1962. In 1966, the city tram produced their first unmanned traction coaches with a red S on a white background. Due to safety reasons, the doors of the side cars and most of the older units had to be manually operated. Nevertheless, individual units which were procured before 1966 were also adapted for one-man operation.

Price struggles, discussions on decommissioning and further rationalisation

[edit]

On 1 and 2 February 1968, the "Freiburg price struggles" caught nationwide attention. At the time, some 2,000 people protested against price increases, occupied Bertoldsbrunnen, and stopped all trams. The protest was unsuccessful.

While many other cities discussed decommissioning trams, Freiburg decided to maintain and modernise towards the end of the 1960s. In 1969, due to the above-average urban planning to the west, a first general traffic plan was adopted. New buildings formed a decisive approach to promote the maintenance and expansion of inner-city tram transport.

In 1971, a small series of modern eight-axle articulated trams manufactured by Duewag was introduced with plans to be further expanded. They could also be operated single-handedly and carry exactly the same number of passengers as the multi-staffed three-car or four-axle units with two-axle side cars. The articulated trams were specially designed for Freiburg's narrow streets, with a four-axle centre wagon and a saddle-mounted end car with a bogie.

In the same year, a rationalisation commission was convened to examine a complete changeover to bus operation.

This is one thing, however, one can completely ignore nowadays: the time of the streets is over. In the future, they will be increasingly degraded in our cities.

— Interim Report of the Rationalisation Commission in 1971

The municipal council endorsed the 1969 general public transport plan in 1972 by a large majority. They thought a connection with trams was more sensible, especially for the western districts. A pedestrian zone on Kaiser-Joseph-Straße was introduced in November 1972. Motorised traffic into the Old City was forbidden and only trams were allowed.[31] From then onwards, investments were made to modernise and accelerate the existing network.

While the inner city ring was being constructed, a single-track parallel section across from the Greifneggring was installed between the Schwabentor and Schwabentorbrücke. At the same time, the existing stretch across the Schwabentorring was restored to provide enough space for separate track space and two lanes of traffic. Due to the connection between the older and newer routes, trams heading towards the city centre from Littenweiler could be reversed before they reached Schwabentor.

On 17 March 1978, the first ceremony for the (almost) urban railway standards with an independent railroad track was extended to Landwasser by Mayor Eugen Keidel and Secretary of State Rolf Böhme. At the start of the 1980s, the first existing stretches of track were given their own reservations, such as the section between Komturplatz and Zähringen.[19] In 1981, the next series of modern articulated trams ended the side carriage operation and the Schaffner era.

Era of the city railways and "environmental season tickets" from 1983/1984

[edit]On 9 December 1983, a new stretch of line was opened heading towards Padauallee is seen as the start of the city railway era. At the heart of the Western Expansion was Stühlinger Bridge, also called City Railway Bridge, which was built over the Rhine Valley Railway and the Höllentalbahn. Since then, the new Hauptbahnhof (main train station) has enabled direct access to the railway lines. In the same year, the VAG increased the voltage from 600 volts to the conventional 750 volts of direct current. When Line 5 was introduced, the line network expanded nd the routes became colour-coded, which are visible as roll signs on each tram. Line 1 replaced Line 4 as the main line, with the new circle routed Line 3. During peak times, trams travelling to the Reutebachgasse terminus could only travel in one direction north of Hornusstraße.

Around that time, a nationwide debate began. It concerned the introduction of a cost-effective and transferable Regio-Umweltkarte (or "environmental protection monthly ticket") based on the system used in Basel, which became operational since 1 March 1984 and was quickly adopted in other Swiss cities such as Bern and Zürich. Associated price reductions were countered by passenger growth, which led to improvements in the company's business. Many German transport companies, including VAG, did not fit into the concept of its high publicity. They were supported by the former Association of German Transport Companies, the municipal top associations and large sections of the scientific community who frequently warned against the introduction of these tickets. "One shied away from new ideas with new risks, was unable to find a general offer for the offensive and therefore conjured up everywhere the fact that environmental issues were only a flop and led to more deficits".[32]

On 24 July 1984, the municipal council decided to introduce the first "environmental protection monthly ticket" despite the VAG rejecting the proposal, and the system began in October.[33] Prices were reduced by at most 30 percent, and the price for the transferable environmental subscriptions was set at 38 Deutsche Marks, or 32 Deutsche Marks a month for concession (the non-transferable monthly ticket cost 51 Deutsche Marks and originally increased to 57 Deutsche Marks in 1985).

This introduction of a cost-effective and transferable monthly ticket caused passenger numbers to rise 12 percent in 1984 and 23 percent the following year, or 5 million to 33.8 million passengers in 1985. Despite the considerable price reduction, the VAG made a profit of 250,000 Deutsche Marks in 1985 alone.[34] Within four years, the number of environmental subscriptions sold rose from 60,500 to 309,000.[35] The ticket served as a breakthrough for German transport companies: "After Freiburg, the trend towards environmental subscriptions could no longer be stopped across Germany."[35]

The Transport Community of Freiburg was founded in 1985, along with the rural districts of Emmendingen and Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald, and Freiburg kept to one tariff zone instead of multiple.[34] The Transport Community of Freiburg, which was purely company-oriented, was a predecessor of the Regio-Verkehrsbund Freiburg (RVF) and was founded in 1994.[36]

The passenger increase that increased by almost 25 percent in a few months was managed relatively well by the tram units. However, because the number of passengers using the network drastically increased in 1985, which was not anticipated by the VAG, ten used GT4-trams from Stuttgart's tram network had to be taken by the company, as the Stadtbahn in Stuttgart began to replace trams. They were the first and only used trams in the history of VAG to be purchased. A novel feature of Freiburg was the use of multiple units and the division of leading and guided units. The trams, referred colloquially as "Spätzlehobel"[37] which were always used in Freiburg in their yellow and white Stuttgart livery, were only replaced by new trams in 1990.

The Regio-Umweltkarte, introduced on 1 September 1991, provided for itself, and previously, its own intermediate stages, partly for increasing passenger growth. The VAG used the outdated Sputnik trams from 1959 until 1993. The Regio-Umweltkarte, in addition to its own monthly ticket, had a connection card available for travel across neighbouring regions costing 15 Deutsche Marks. In 1987, the Regio-Umweltkarte reduced ticket prices by about 25 percent (which was also the case in Basel), which led to a spark in further traffic and environmental issues across Germany[34]

In 1985, the VAG completed the project of providing a tram line to Landwasser by extending the former terminus at Paduaallee by 1.8 kilometres over Elsässer Straße and reaching Moosweiher.

In the following year, a new route from Friedrich-Ebert-Platz to Hohenzollernstraße, Breisacher Straße and Fehrenbachallee replaced the old route via Hugstetter Straße and the station court, causing Lines 3 and 4 to cross over Stühlinger bridge.[38]

Start of the low-floor age

[edit]

When the first GT8N series motor trams were delivered, the VAG began offering its passengers a low-floor entry starting in 1990. It was to be the third tramway network to do so after Würzburg and Bremen. The rapid development of low-floor technology during these years reflected in Freiburg's acquisition of trams. If the first trams only had a low-floor section of seven percent and a depth rise of five doors, the second low-floor generation in 1994 had a low-floor section of 48 percent and barrier-free access to three out of the four doors. From 1999, only low-floor units were purchased. VAG equipped almost all the older stops across the network with 24-centimetre high platforms.

In March 1994, the three-kilometre long extension between Runzmattenweg and Bissierstraße built in 1983 became accessible to the Haid industrial park via vineyards. The route runs parallel to Berliner Alllee and crosses the B31 and the Dreisam. In the vineyard, the route runs along a track to the west of Binzengrün Straße before turning onto Opfinger Straße. The route crosses Besançonallee and reaches the western depot, where it runs on its own rail west of Besançonallee to Munzinger Straße, which meant the Western Railway Depot received a railway link for the first time.

The depots at Komturstraße and Urachstraße were less important. The northern depot was demolished in 2007, while the southern depot became a museum.

The link to the newly developed district of Rieselfeld was established in 1997. On this 1.3 kilometre section, the route runs on a ridged track in the middle of Rieselfeldallee and serves three stops at Geschwister-Scholl-Platz, Maria-von-Rudloff-Platz and Bollerstaudenstraße. The terminal loop at Rieselfeld turns around a residential building, the "Tram-Turm".

On 3 June 2002, the VAG introduced a relief Line 8 from Munzinger Straße to Stadthalle in 15-minute cycles, which was discontinued on 27 July 2002.

After 40 years, the Haslach district had a tram network when Line 7 was first opened between Am Lindenwäldle and Pressehaus in October 2002. The route follows the vineyard route and runs to the north of Opfinger Straße to the crossing of the freight railway, then goes down Carl-Kistner-Straße and serves Haslach Bad, Scherrerplatz and Dorfbrunnen in the middle of Haslach. There was controversy when the link connecting Pressehaus and the Innenstadt happened: although the majority voted for the route to lead to Stadttheater via Kronenstraße in 1997, the municipal council voted for a different route via Basler Straße to Johanniskirche.[39] In 2004, the entire route between Am Lindenwäldle and Johanniskirche became operational as Line 5. The costs for this project amount to about 30 million Euros. Later, it was decided to implement the first-named routed as part of the "Stadtbahn Rotteckring".[citation needed]

The district of Vauban, built on the site of a former barracks in 1998, also had access to the tram network in 2006 after three years of construction.[40][41] The cost amounted to 18 million euros instead of the originally estimated 30 million.[42] The 2.5 kilometre long section branches off from the route towards Haslach to Merzhauser Straßer after the stop at Heinrich-von-Stephan-Straße, and runs mostly along a road towards Merzhauser Straße. At Paula-Modersohn-Platz, the route turns into Vaubanallee and runs mainly northwards until its final stop at Innsbrucker Straße.

Expansion program "Stadtbahn 2020" and night trams

[edit]Between February 2009 and November 2010, the section of the track[clarification needed] was completely renovated by Habsburger Straße. In addition, three stops at Tennenbacher Straße, Hauptstraße and Okenstraße were adapted to operate without barriers.[43] The section between Maria-Hilf-Kirche and Musikhochschule along Schwarzwaldstraße was modernised in 2011.[44]

On 15 March 2014, the 1.8 kilometre stretch was opened from Reutebachgasse to the centre of Zähringen at Gundelfinger Straße after three years of construction. Part of this project included the construction of the stop at Reutebachgasse. The route follows Zähringer Straße, crosses the freight railway and runs on its own line west of Gundelfinger Straße to the southern outskirts of Gundelfingen. Part of the terminal loop is located at the Gundelfinger boundary, so trams leave the region of Freiburg here. The cost of this construction project was 24.5 million euros.[45]

From the beginning of June to the end of October 2014, tracks at the junction of Bertoldsbrunnen were renovated after the points broke.[46] During the renovation, all lines had to be relocated to the edge of the inner city (Siegesdenkmal, Stadttheater, Holzmark and the Schwabentor loop). During this time the GT8N-operated Line 1 heading east was operational, because a provisional depot had to be erected at Möschlschleife due to the lack of a track connection to the depot.[47]

When the timetable changed on 14 December 2014, the city council decided to reduce the noise in the inner city by providing a continuous night service in 30-minute cycles on Saturday, Sunday and pre-selected holidays, except for the sections between Johanniskirche and Günterstal, and Technisches Rathaus and Hornusstraße.[48] This cost around 550,000 euros yearly and, according to VAG, has been seen as a positive move. By counting the number of passengers on the night services in November 2014, it was reported that a high four-digit number of passengers use the service nightly.[49]

The next expansion was the Stadtbahn Messe, for which construction started on 14 June 2013, and which opened to Technische Fakultät on 11 December 2015 and to the Messe on 13 December 2020. The 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi)-long initial phase crosses the network at Robert-Koch-Straße and continues via Breisacher Straßer and Berliner Allee to Technische Fakultät just to the north of the Freiburg-Colmar railway link, while the second phase continues a further 970 metres (3,180 ft) to Messe. The new Line 4 was initially marked as MESSE (in uppercase lettering) before being changed to Messe in February 2016.[50][51][52]

In 2019 the System received a new major expansion with the completion of the Rotteckring tram. This added a new north–south line through the city center. The new line divirges from the existing network at Heinrich-von-Stehpan-Straße, crosses the Dreisam on the Kronenbrücke, which was rebuilt during construction of the expansion, before entering the city center. This also added stops at existing stations Stadttheater and Europaplatz. The line opened on 16 March 2019.[53]

On 14 June 2023, the new Stadtbahn Waldkircher Straße opened. Part of the existing tram tracks of line 2 running through Komturstraße were moved into Waldkircher Straße in order to better connect the main parts of the district and to make it possible for the stations to be barrier-free, as the previous stops Komturplatz and Eichstätter Straße were on the street itself.[54]

On 15 December 2024, a new timetable will be introduced, which comprises major changes in routing for the first time since 2019. Line 3 will take over the northern branch of line 4 from Bertoldsbrunnen to Zähringen, and line 4 the southern branch of line 3 from Bertoldsbrunnen to Vauban.[55]

Operations

[edit]Overview

[edit]The five tram lines, all of which are cross-city routes, serve a total of 78 stops. The average distance between stops in 2012 was 456 metres.[56] Trams run between 5 am and 12:30 am Monday to Friday, and non-stop on weekends. The line length is 32.3 kilometres, and cumulatively 40 kilometres.[57] VAG operates a total of 24 substations with an installed total transformer capacity of 33.75 megavoltamperes (MVA).[58]

| Line | Route | Stops | Cycle | Length | Journey time | Mode | Trams used | Courses at one time | Course numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Littenweiler, Laßbergstraße[59] - Landwasser, Mossweiher | 22 | 6 mins | 9.9 km | 31mins | Unidirectional | GT8K, GT8N, GT8Z (rarely),

Combino, Urbos |

16 | 01 - 115 |

| 2 | Günterstal, Dorfstraße - Hornusstraße | 20 | 10 mins | 8,0 km | 30mins | Bidirectional | GT8Z | 8 | 220 - 227 |

| 3 | Vauban, Innsbrucker Straße - Haid, Munzinger Straße | 21 | 7.5 mins | 9.2 km | 32mins | Unidirectional | GT8K, GT8N, GT8Z, Combino,

Urbos |

11 | 330 - 341 |

| 4 | Messe Freiburg - Zähringen, Gundelfinger Straße | 20 | 6min; 7.5 mins | 9.2 km | 32mins | Unidirectional | GT8K, GT8N, GT8Z, Combino,

Urbos |

12 | 442 - 453 |

| 5 | Rieselfeld, Bollerstaudenstraße - Europaplatz | 15 | 6min; 7.5 mins | 6,3 km | 20 mins | Bidirectional | GT8Z, Combino, Urbos | 8 | 565 - 572 |

- GT8K, GT8N, Combino and Urbos cannot be used on line 2 because they are unsuitable for the route, as the terminal station in Günterstal is too short and does not have a loop for unidirectional trams to turn around.

- The GT8Z is usually not used on line 1 because its capacity is too low for the line's demand, making it a rather rare sight.

- In the evenings from 9 pm to 11:01 pm, lines 1, 2, 3 and 4 meet in both directions for minutes 01, 16, 31 and 46 to form a circular enclose at Bertoldsbrunnen. After this time, they wait until 01 and 31.

- A night service leaves every 30 minutes from Bertoldsbrunnen between 1 am and 4:30 on Saturday, Sunday and on selected bank holidays on Lines 1, 3, 4 and the Rieselfeld-Europaplatz section of line 5.[60] Günterstal and other inner- and non-urban destinations are connected to the night service in the form of taxis and buses.[61]

- Trams heading to and from the depot at VAG-Zentrum are marked with the red slash that is used for lineless operation instead of a line number. Trams coming from the depot stay this way until they arrive at the terminal station of the line which it then switches to. Trams heading to the depot have Am Lindenwäldle as their destination and final stop, as this is the last one before the trams turn rightward onto the area of the VAG-Zentrum.

- The unidirectional tram models travel in reverse when heading to and from the Depot before switchting direction at a crossover. This procedure is done in the sections VAG-Zentrum to Runzmattenweg (line 1) and Heinrich-von-Stephan-Straße to Vauban, Innsbrucker Straße (line 3).

- With the exception of Bertoldsbrunnen, Klosterplatz and Oberlinden, all stations have platforms with barrier-free access to low-floor vehicles.

- Course numbers are not stated by lines (for example, line 3, course 1) but by a three-digit number range. It was originally a two-digit range.[62]

- Apart from the terminus stops, all stops along Freiburg's tram network are request stops.

Special service to the Europa-Park-Stadion

[edit]When there is an SC Freiburg home game in the Europa-Park-Stadion, four special service lines start three hours prior to kick-off. They run as express trains from Hauptbahnhof, Zähringen (non-stop from Friedrich-Ebert-Platz), and Landwasser (non-stop from Runtzmattenweg). The fourth line runs from Munzinger Straße and stops at all stations. After the game the special service lines start from the triple platform Europa-Park-Stadion Station and run express to Rathaus im Sthülinger and Friedrich-Ebert-Platz.[63]

Tariff

[edit]Trams have been a part of the Regio-Verkehrsverbund Freiburg (RVF) since 1994. The entire network is located within tariff zone A, which means that a tram ride has a level 1 tariff. The pass is called the "Regio-Karte": it is readily available and is valid throughout the network. Single tickets cost 2.30 euros for general, and 1.40 euros for children up to 14 years of age. Day tickets (Regio 24) and various other tickets are also available. Bikes are not permitted on any tram on the network.[64]

There are ticket machines in each carriage and at important stops. Passengers cannot buy tickets from the driver since the start of 2016.[65]

Development of passenger numbers

[edit]| 1902 | 1919 | 1923 | 1936 | 1984 | 1985 | 2000 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,250,000 | 14,600,000 | 800,000 | 9,400,000 | 29,000,000* | 33.800,000* | 65,000,000* | 63,400,000* |

* Passenger numbers from 1984, 1985 and 2000 also include buses and rail replacement services, as there is no explicit data for these years.

Route timeline

[edit]The following table shows all openings and closures in passenger-oriented trams. Temporary routes are not included.

| Route | Opened | Closed |

|---|---|---|

| Günterstal - Bertoldsbrunnen - Rennweg | 14 October 1901 | |

| Hauptbahnhof - Bertoldsbrunnen - Alter Messplatz | 2 December 1901 | |

| Schwabentorbrücke - Alter Wiehrebahnhof - Lorettostraße | 2 December 1901 | |

| Hauptbahnhof - Lehener Straße | 1902 | |

| Alter Messplatz - Musikhochschule | 1905 | |

| Lehener Straße - Friedrich-Ebert-Platz - Güterbahnhof | 1908 | |

| Rennweg - Okenstraße | 1908 | |

| Siegesdenkmal - Hauptbahnhof | 17 June 1909 | |

| Siegesdenkmal - Stühlinger Kirchplatz | 1 September 1909 | |

| Okenstraße - Komturplatz - Reutebachgasse | 10 March 1910 | |

| Lorettostraße - Goethestraße | December 1910 | |

| Stühlinger Kirchplatz - Scherrerplatz | October 1913 | |

| Siegesdenkmal - Immentalstraße | 1 July 1914 | |

| Musikhochschule - Römerhof - Bahnhof Littenweiler | 7 March 1925 | |

| Kaiserstuhlstraße - Güterbahnhof | 1928 | |

| Kaiserstuhlstraße - Komturplatz | 1928 | |

| Lorettostraße - Goethestraße | 15 October 1931 | |

| Immentalstraße - Herdern Kirche | 1 July 1951 | |

| Schwabentorbrücke - Alter Wiehrebahnhof - Lorettostraße | 1959 | |

| Scherrerplatz - Wilhelmerstaße and Hauptbahnhof -

Siegesdenkmal - Herdern Kirche |

31 December 1961 | |

| Laßbergstraße - Bahnhof Littenweiler | 20 December 1962 | |

| Stadttheater - Rathaus im Stühlinger - Paduaallee | 9 December 1983 | |

| Runzmattenweg - Bissierstraße | 9 December 1983 | |

| Paduaallee - Moosweiher | 14 June 1985 | |

| Rathaus im Stühlinger - Friedrich-Ebert-Platz | 27 September 1986 | |

| Hauptbahnhof - Hugstetter Straße - Friedrich-Ebert-Platz | 27 September 1986 | |

| Bissierstraße - Am Lindenwäldle - Munzinger Straße | 26 March 1994 | |

| Am Lindenwäldle - Bollerstaudenstraße | 14 September 1997 | |

| Am Lindenwäldle - Pressehaus | 12 October 2002 | |

| Pressehaus - Johanneskirche | 20 March 2004 | |

| Heinrich-von-Stefan-Straße - Innsbrucker Straße | 29 April 2006 | |

| Reutebachgasse - Gundelfinger Straße | 15 March 2014 | |

| Robert-Koch-Straße - Technische Fakultät | 11 December 2015 | |

| Heinrich-von-Stephan-Straße - Europaplatz | 16 March 2019 | |

| Technische Fakultät - Messe Freiburg | 13 December 2020 |

Line timeline

[edit]Lines were originally given letters before they were assigned Arabic numerals in 1909. Each line had its own destinations, which differed in colour. Lines were officially colour-coded in the summer of 1921. The VAG introduced a line reform in 1983, when the colours of the lines were changed and coloured roll signs were introduced to display the line number.

Daily usage

[edit]| Line | Route | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Hauptstraße (formerly: Rennweg) – Europaplatz (formerly: Siegesdenkmal) – Bertoldsbrunnen – Lorettostraße | 14 October 1901 | 1908 |

| Okenstraße (formerly: Roßgäßle) – Europaplatz (formerly: Siegesdenkmal) – Bertoldsbrunnen – Lorettostraße | 1908 | 16 June 1909 | |

| 1 | 17 June 1909 | 14 April 1921 | |

| 15 April 1921 | 27 November 1944[a] | ||

| 13 March 1946 | 19 December 1962 | ||

| Hornusstraße – Europaplatz (formerly: Siegesdenkmal) – Bertoldsbrunnen – Lorettostraße | 20 December 1962 | 8 December 1983 | |

| 1 | Laßbergstraße – Schwabentorbrücke – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Runzmattenweg – Paduaallee | 9 December 1983 | 13 June 1985 |

| Laßbergstraße – Schwabentorbrücke – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Runzmattenweg – Moosweiher | 14 June 1985 | today | |

| D | Hauptstraße (formally: Rennweg) – Siegesdenkmal – Bertoldsbrunnen – Dorfstraße | 14 October 1901 | 1908 |

| Okenstraße (formally: Roßgäßle) – Europaplatz (formerly: Siegesdenkmal) – Bertoldsbrunnen – Dorfstraße | 1908 | 16 June 1909 | |

| 2 | 17 June 1909 | 9 March 1910 | |

| Reutebachgasse – Europaplatz (formerly: Siegesdenkmal) – Bertoldsbrunnen – Dorfstraße | 10 March 1910 | 14 April 1921 | |

| 15 April 1921 | 27 November 1944[a] | ||

| Holzmarkt – Dorfstraße | 28 November 1944 | 15 May 1945 | |

| 25 May 1945 | 3 October 1945 | ||

| Reutebachgasse – Komturplatz | 25 June 1945 | 3 October 1945 | |

| Reutebachgasse – Europaplatz (formerly: Siegesdenkmal) – Bertoldsbrunnen – Dorfstraße | 4 October 1945 | September 1996 | |

| 29 April 2006 | 14 March 2014 | ||

| Gundelfinger Straße – Europaplatz (formerly: Siegesdenkmal) – Bertoldsbrunnen – Dorfstraße | 15 March 2014 | 10 December 2015 | |

| Hornusstraße – Europaplatz (formerly: Siegesdenkmal) – Bertoldsbrunnen – Dorfstraße | 11 December 2015 | 16 March 2019 | |

| Hornusstraße - Friedrich-Ebert-Platz - Hauptbahnhof - Bertoldsbrunnen - Dorfstraße | 16 March 2019 | today | |

| C | Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Alter Messplatz (formerly: Bleicheweg) | 2 December 1901 | 1902 |

| Lehener Straße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Alter Messplatz (formerly: Bleicheweg) | 1902 | 1905 | |

| Lehener Straße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Musikhochschule (formerly: Waldsee) | 1905 | 1908 | |

| Güterbahnhof – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Musikhochschule (formerly: Waldsee) | 1908 | 16 June 1909 | |

| 3 | 17 June 1909 | 14 April 1921 | |

| 3 | Güterbahnhof – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Alter Messplatz (formerly: Bleichestraße) | 15 April 1921 | 7 March 1925 |

| Güterbahnhof – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Musikhochschule (formerly: Waldsee) | 8 March 1925 | 1928 | |

| Friedrich-Ebert-Platz (formerly: Hohenzollernplatz) – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Musikhochschule (formerly: Waldsee) | 1928 | 1938 | |

| Friedrich-Ebert-Platz (formerly: Hohenzollernplatz) – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Römerhof (formerly: Wendelinstraße) | 1938 | 27 November 1944[a] | |

| 3 | 13 March 1946 | 1953–1957 | |

| Hauptfriedhof (formerly: Friedhof) – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Römerhof | 1953-1957 | 19 December 1962 | |

| Hauptfriedhof (formerly: Friedhof) – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Laßbergstraße | 20 December 1962 | ? | |

| Hornusstraße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Laßbergstraße | ? | 8 December 1983 | |

| 3 | Circular route: Hornusstraße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Siegesdenkmal – Hornusstraße (– Reutebachgasse)[b] | 9 December 1983 | 26 September 1986 |

| Circular route: Hornusstraße – Robert-Koch-Straße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Siegesdenkmal – Hornusstraße (– Reutebachgasse)[b] | 27 September 1986 | September 1996 | |

| Oldtimerlinie:[c] Paduaallee – Runzmattenweg – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Musikhochschule (formerly: Stadthalle) | September 1996 | 1 October 2005 | |

| Innsbrucker Straße – Heinrich-von-Stephan-Straße – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Runzmattenweg – Munzinger Straße | 29 April 2006 | 14 December 2024[66] | |

| B | Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Alter Wiehrebahnhof (formerly: Bahnhof Wiehre) – Lorettostraße | 2 December 1901 | 1902 |

| Lehener Straße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Alter Wiehrebahnhof (formerly: Bahnhof Wiehre) – Lorettostraße | 1902 | 16 June 1909 | |

| 4 | 17 June 1909 | December 1910 | |

| Lehener Straße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Alter Wiehrebahnhof (formerly: Bahnhof Wiehre) – Goethestraße | December 1910 | 14 April 1921 | |

| 4 | Lehener Straße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Musikhochschule (formerly: Waldsee/Mösle) | 15 April 1921 | 6 March 1925 |

| Lehener Straße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Bahnhof Littenweiler | 7 March 1925 | 1928 | |

| Komturplatz – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Bahnhof Littenweiler | 1928 | 27 November 1944[a] | |

| Oberlinden – Schwabentorbrücke – Bahnhof Littenweiler | 28 November 1944 | 15 May 1945 | |

| 25 May 1945 | 12 March 1946 | ||

| Komturplatz – Friedrich-Ebert-Platz (formerly: Hohenzollernplatz) | 25 June 1945 | 12 March 1946 | |

| Komturplatz – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Bahnhof Littenweiler | 13 March 1946 | 19 December 1962 | |

| Hornusstraße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Lassbergstraße | 20 December 1962 | 8 December 1983 | |

| 4 | Hornusstraße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Lorettostraße (– Dorfstraße)[b] | 9 December 1983 | 26 September 1986 |

| Hornusstraße – Robert-Koch-Straße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Lorettostraße (– Dorfstraße)[b] | 27 September 1986 | September 1996 | |

| Hornusstraße – Robert-Koch-Straße – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Dorfstraße | September 1996 | 28 April 2006 | |

| 4 | Gundelfinger Straße – Siegesdenkmal – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Robert-Koch-Straße – Technische Fakultät | 11 December 2015 | 12 December 2020 |

| Gundelfinger Straße – Europaplatz – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Robert-Koch-Straße – Messe Freiburg | 13 December 2020 | 14 December 2024[66] | |

| 5 | Siegesdenkmal – Hauptbahnhof | 17 June 1909 | 31 August 1909 |

| Siegesdenkmal – Hauptbahnhof – Eschholzstraße (formerly: Stühlinger Kirchplatz) | 1 September 1909 | October 1913 | |

| Siegesdenkmal – Hauptbahnhof – Eschholzstraße (formerly: Stühlinger Kirchplatz) – Scherrerplatz | October 1913 | 22 November 1919 | |

| Immentalstraße – Siegesdenkmal – Hauptbahnhof – Eschholzstraße (formerly: Stühlinger Kirchplatz) – Scherrerplatz | 23 November 1919 | 14 April 1921 | |

| 15 April 1921 | 27 November 1944[a] | ||

| Eschholzstraße (formerly: Stühlinger Kirchplatz) – Scherrerplatz | 1 September 1946 | 14 April 1949 | |

| Immentalstraße – Siegesdenkmal | 18 October 1946 | 14 April 1949 | |

| Immentalstraße – Siegesdenkmal – Hauptbahnhof – Eschholzstraße (formerly: Stühlinger Kirchplatz) – Scherrerplatz | 15 April 1949 | 30 June 1951 | |

| Herdern Kirche – Siegesdenkmal – Hauptbahnhof – Eschholzstraße (formerly: Stühlinger Kirchplatz) – Scherrerplatz | 1 July 1951[67] | 31 December 1961 | |

| Bissierstraße – Runzmattenweg – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Siegesdenkmal – Hornusstraße (– Reutebachgasse)[b] | 9 December 1983 | 25 March 1994 | |

| Munzinger Straße – Runzmattenweg – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Siegesdenkmal – Hornusstraße (– Reutebachgasse)[b] | 26 March 1994 | 19 March 2004 | |

| Bollerstaudenstraße – Scherrerplatz – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Runzmattenweg – Bissierstraße | 20 March 2004 | 28 April 2006 | |

| Bollerstaudenstraße – Scherrerplatz – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Robert-Koch-Straße – Hornusstraße | 29 April 2006 | 14 March 2014 | |

| Bollerstaudenstraße – Scherrerplatz – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Robert-Koch-Straße – Hornusstraße (– Gundelfinger Straße)[b] | 15 March 2014 | 15 March 2019 | |

| Bollerstaudenstraße – Scherrerplatz – Stadttheater – Europaplatz | 16 March 2019 | today | |

| 6[d] | Immentalstraße – Siegesdenkmal | 1 July 1914 | 22 November 1919 |

| Schwabentorbrücke – Alter Wiehrebahnhof (formerly: Bahnhof Wiehre) – Goethestraße | 15 April 1921 | 16 October 1922 | |

| 22 December 1924 | 15 October 1931 | ||

| Schwabentorbrücke – Alter Wiehrebahnhof (formerly: Bahnhof Wiehre) | 16 October 1931 | 9 November 1934 | |

| Schwabentorbrücke – Alter Wiehrebahnhof – Lorettostraße | 1940 | 1943 | |

| 1 September 1946 | 19 November 1950 | ||

| 6 | Bollerstaudenstraße – Runzmattenweg – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Siegesdenkmal – Reutebachgasse | 14 September 1997 | 19 March 2004 |

| Munzinger Straße – Runzmattenweg – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Siegesdenkmal – Reutebachgasse | 20 March 2004 | 28 April 2006 | |

| 7 | Munzinger Straße – Scherrerplatz – Pressehaus | 12 October 2002[68] | 19 March 2004 |

| 7 | Oldtimerlinie:[c] Musikhochschule – Runzmattenweg – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Paduaallee | 6 May 2006 | today |

| 8 | Munzinger Straße – Runzmattenweg – Hauptbahnhof – Bertoldsbrunnen – Schwabentorbrücke – Musikhochschule (formerly: Stadthalle) | 3 June 2002 | 27 July 2002 |

- ^ a b c d e Bombing of Freiburg on 27 November 1944

- ^ a b c d e f g Only for professional traffic

- ^ a b Only on the first Saturday between months May and September operated by the Freunde der Freiburger Straßenbahn (Friends of Freiburg's Tramways).

- ^ Destination board was divided diagonally. Upper left white and lower right red.

Night service

[edit]The night service "Safer Traffic" was originally served by buses from 1996, but have largely been tram-operated since 14 December 2014. There is currently no service due to the Covid-19 Pandemic.[69][70]

| Line | Route | From | Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Laßbergstraße – Schwabentorbrücke – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Runzmattenweg – Moosweiher | 14 December 2014 | today |

| 2/5 | Gundelfinger Straße – Siegesdenkmal – Bertoldsbrunnen – Scherrerplatz – Bollerstaudenstraße | 14 December 2014 | 6 December 2015 |

| 3 | Innsbrucker Straße – Heinrich-von-Stephan-Straße – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Runzmattenweg – Munzinger Straße | 14 December 2014 | today |

| 4 | Gundelfinger Straße – Europaplatz – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Robert-Koch-Straße – Messe | 11 December 2015 | today |

| 5 | Bollerstaudenstraße – Scherrerplatz – Bertoldsbrunnen | 11 December 2015 | March 2019 |

| 5 | Bollerstaudenstraße – Scherrerplatz – Europaplatz | March 2019 | today |

Trams

[edit]Currently used trams

[edit]

GT8K

[edit]In 1981, after a good experience with the Duewag GT8 Geamatic, which was delivered in 1971, another ten vehicles were commissioned with service numbers 205–214 on the route to Landwasser. The high-floor uni-directional trams were delivered with the white and red Freiburg livery and have two front headlights. The seats are arranged transversely in the diagram 2+1 instead of the mechanical stepped cruise control of earlier trams. The second series used for the first time a direct current controller, which was operated via set point transmitter. It allows a largely jerk-free acceleration and deceleration. Compared to the first series, which had scissor pantographs , the second series had single-arm pantographs.

Tram 205 is now used as an historic tram, tram 207 was scrapped in 2007, and trams 208 and 209 were sold to the Ulm tram network in 2008.[71]

Since 2006, trams are usually limited to the morning rush hour or as an additional service to SC Freiburg's home games. From 2012 to 2017, trams 206 and 210–214 were reused due to the GT8Zs' renovation. For this purpose, tram 206, which had not been used for years, was reactivated, and was the first tram to have an LED display, while the remaining vehicles were renovated in March 2013. Due to the introduction of the second Urbos series at the start of 2017, tram 206 was retired again.[72] The remaining two GT8Ks (212,214) will only operate on Lines 1 (during peak times), 3 and 4, as well as for stadium transportation from Mondays to Fridays.[73]

GT8N

[edit]In 1990, Duewag delivered another series of eleven developed GT8s for a unit price of 2.75 million Deutsche Marks. Unlike its predecessors, the GT8Ns 221–231 have a low-floor middle section that allow barrier-free entry. Firstly, the GT8N were primarily used on Line 1, where they replaced the GT4 procured from Stuttgart.[73]

In contrast to the GT8K, the GT8N were also equipped with scissor pantographs. In 2011, all trams had a matrix display installed. The trams were modernised by the Czech company Cegelec, who replaced the obsolete thyristor technology with relatively new insulated-gate bipolar transistor technology.[74] The aim of this measure was to extend the service life of the vehicles, reduce maintenance costs and electricity consumption, and improve the availability of spare parts. The modernisation process was completed in 2011.

In recent years, the GT8N's usage has been shifted to lines 3 and 5. The 11 trams are generally only used on weekdays.

GT8Z

[edit]

At the beginning of the 1990s, Freiburg was looking for modern low-floor trams, and the city ordered a series of 26 GT8Z (241–266) in 1994 to start the Haid route. The purchase price was 4 million Deutsche Marks each. Meanwhile, the remaining GT4s were decommissioned.[73] The bi-directional trams could be used across all lines.

For more than 20 years of operation, there were some instances of rusting on the trams, but this has been eradicated since they were modernised in 2012.[73] Outdated transistors were replaced at the Siemens Test Centre at Wildenrath, and Cegelec replaced the electronics (including two new LCDs in the centre cabin) and the seat cushions.[75] Trams 241–245, 247, 250–252, 258, 259, 262 and 264 have been completely renovated. In early 2017, trams 248, 249, 260 and 266 were being modernised and removed from operation. After a test phase in 2013, during which time operation on line 3 was limited, trams that had been modernised were running on lines 2 and 5 from March 2014.

Tram 243 was damaged in a severe crash on 2 February 2023 and will most likely not return into service.[76]

Combino Basic

[edit]When the route to Rieselfeld and Haslach had been opened, the need for trams continued to rise. For this reason, a series of nine trams was ordered from Duewag's successor company Siemens. The first seven-part bi-directional trams were delivered in 1999.[73]

Because of serious design deficiencies (such as loose screws from improper calculations), all Combinos were withdrawn from circulation in 2004. Erroneous values were calculated on high-floored units. Tram 272 was artificially aged in order to gain more insights into the strength of the bodies.[77] The Combinos were refurbished until 2007, but trams 271 and 273-279 are fully operational again.

Combino Advanced

[edit]

The Combino Advanced was built by Siemens and were initially made available free of charge to VAG.[73] In this series, which was delivered in 2004 and 2006 with operating numbers 281–290, the bodies were reinforced in order to avoid problems that the Basic model experienced. Only nine units were planned originally, while car 290 was delivered as a replacement for the scrapped 272 Combino.

The seven-part bi-directional trams differed from their predecessors by having a rounder-shaped head, and the entire passenger section was air-conditioned.

Urbos

[edit]

On 4 February 2013, the Spanish company CAF was awarded the contract to produce twelve 43-metre long seven-sectioned bi-directional trams.[78][79][80] The purchase price was 36 million euros. The first tram was numbered 302 and arrived on 17 March 2015.[81] Five other trams from the first series, numbers 301, 303-306 were delivered during the summer of 2015.[82] Regular deployment began on 22 July 2015 after trial and training trips.[83] The new trams serve Lines 1, 3, 4 and 5. Numbers 307 to 312 were delivered between February and July 2017.[84][85] As of November 2021, there are 17 Urbos currently being used. (301–317)

Future trams

[edit]The VAG has ordered another eight Urbos trams, which are expected to be delivered in 2023 and 2024, and are intended to replace the remaining GT8N and GT8K.[86][87]

Former and museum trams

[edit]Railcars

[edit]The following rail cars were procured for trams, which are no longer used for regular services. Until 1959, the company only had access to two-axle or short four-axle maximum rail cars, and only articulated trams since then. Large-scale units were never used in Freiburg, and all previously cancelled units were high-floored.

The remaining trams are partly used on the Oldtimerlinie 7 operated by Freunde der Freiburger Straßenbahn. In the months of May to September, the route between Paduaallee and Stadthalle happened on the first Saturday of the month, and stops at all intermediate stations could be used free of charge.[88] Historic trams are stationed in the former southern depot at Urachstraße.

| Photo | Number | Unit | Manufacturer | Type | Kind | Year of construction | In service until | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–27 | 27 | HAWA | Two-axle | Bi-directional | 1901 | 1954 | Number 2 kept as a museum tram | |

| 28–30 | 3 | Waggonfabrik Rastatt | Two-axle | Bi-directional | 1907 | 1960 | ||

| 31–40 | 10 | MAN | Two-axle | Bi-directional | 1909 | 1962 | Number 38 work tram, now kept as a museum tram | |

|

41–47 | 7 | MAN | Two-axle | Bi-directional | 1914 | 1966 | Number 42 was handed over to the Museum of Automotive Engineering at Marxzell in 1972 and kept as a museum tram |

| 47–52 | 6 | Waggonfabrik Fuchs | Maximum railcar | Bi-directional | 1927 | 1968 | ||

|

53–61 | 9 | Waggonfabrik Rastatt | Maximum railcar | Bi-directional | 1927–1929 | 1978 | Number 56 kept as a museum tram |

|

61–74 | 14 | Waggonfabrik Rastatt | Multi-purpose | Bi-directional | 1951–1953 | 1972 | Number 61 in second usaage, first Freiburg tram with steel construction

Number 70 kept as a museum tram Number 72 was renamed tram 406 |

|

100–102 | 3 | Waggonfabrik Rastatt | Sputnik | Uni-directional | 1959 | 1993 | First articulated tram in Freiburg, named after the satellite of the same name

100 (1967-1994 as 103), was reused as a rehabilitation tram and since 2006 museum tram 101 and 102 were scrapped in 1995. |

|

104–122 | 19 | 104–114: Maschinenfabrik Esslingen

115–122: Waggonfabrik Rastatt |

GT4 | Bi-directional | 1962–1968 | 1994 | Sold to the tramway of Brandenburg an der Havel, tramway of Halberstadt and Nordhausen after decommissioning

107 in reprocessing 109 as a museum car 121 as a party car |

|

151–160 | 10 | Maschinenfabrik Esslingen | GT4 | Uni-directional | 1964 | 1990 | Taken from Stuttgart in 1985

After decommission, given to the Halle tramway, 151–157 moved to Iași, and 158–160 were scrapped. |

|

201–204 | 4 | Duewag | GT8 | Uni-directional | 1972 | 2001 | With Geamtic control

Used in Łódź from 2006 to 2012, later scrapped or used for spare parts |

Sidecars

[edit]Departmental vehicles

[edit]Originally, the departmental trams were numbered up from 200.[89] Since 1971, they were numbered from 400 since the GT8 at the time was numbered 200.

| Number | Type | Manufacturer | Year of construction | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 201 | Water Tram | Helmers | 1901 | In use until 1950, given to the Middle Baden Train Network |

| 201II | Auxiliary Equipment Tram | HAWA | 1901, Renovated 1950 | Originated from railcar 27, in use until 196 |

| 202 | Water Tram | Helmers | 1909 | In use until 1950 |

| 203 | Grinder Tram | Schörling | 1914 | From 1971, new number 414, in use until 1982, kept as a museum tram |

| 204 | Salt Tram | Helmers | 1901 | With snowplow, in use until 1968 |

| 205 | Salt Tram | Eigenbau | 1909 | In use until 1971, last number 415 |

| 207 | ? | HAWA | 1901, Renovated 1954 | Former railcar 13, in use until 1961 |

| 208 | ? | HAWA | 1901, Renovated 1954 | Former railcar 14, in use until 1962 |

| 209 | ? | HAWA | 1901, Renovated 1954 | Former railcar 15, in use until 1962 |

| 209II | Transportation Tram | ? | 1962 | From 1971, new number 416 |

| 210 | ? | HAWA | 1901, Renovated 1954 | Former railcar 21, in use until 1962 |

| 210II | Transportation Tram | ? | 1962 | From 1971, new number 417 |

| 211 | ? | HAWA | 1901, Renovated 1954 | Former railcar 12, in use until 1961 |

| 212 | ? | HAWA | 1901, Renovated 1954 | Former railcar 17, in use until 19XX |

| 401 | Driving School Tram | Waggonfabrik Rastatt | 1951, Renovated 1970 | Former railcar 65, decommissioned |

| 402 | Catenary Tram | Waggonfabrik Rastatt | 1951, Renovated 1970 | Former railcar 70, rebuilt to original condition in 2016, planned use as a museum wagon |

| 403 | Workshop Tram | Waggonfabrik Rastatt | 1951, Renovated 1971 | Former multi-purpose tram, decommissioned |

| 404 | Workshop Tram | Waggonfabrik Rastatt | 1951, Renovated 1971 | Former multi-purpose tram, decommissioned |

| 405 | Workshop Tram/

Grinder Tram |

Waggonfabrik Rastatt | 1951, Renovated 1979 | Formerly railcar 66, initially workshop tram

From 1982, a grinder tram, sold in 2012 to Halberstadt |

| 406 | Workshop Tram | Waggonfabrik Rastatt | 1951, Renovated 1971 | Former multi-purpose tram, given to the Bergish Tram Museum in 2002 |

| 406II | Track Grinding Tram SF 50 | Windhoff | 2012 | Four grinding wheels, still in use today |

| 407 | Workshop Tram | Waggonfabrik Rastatt | 1951, Renovated 1971 | Former multi-purpose tram, decommissioned |

| 407II | Maintenance Klv53Cl | Schöma | 1982 | Snowplow with diesel engine |

| 411 | Tipper truck | DIEMA | 1982 | |

| 412 | Tipper truck | DIEMA | 1982 | Sold to Romania |

Paintwork and advertisement

[edit]

The general paintwork for all municipal trams in 1901 was yellow with brown side panels made of teak. Advertisement was strictly rejected since "the elegance of the tram" would suffer considerably.[90]

We do not deny the effectiveness of advertising on our trams, but we doubt that it will contribute to the increase in tourism, when posters are placed on the wage, with the recommendation of water, alcohol-free drinks, cigarettes etc."

— Representative of the municipal tram network in a statement given in 1919

There was only a lull in the ban on advertising during the economic crisis of July 1919. Since them, internal commercial advertising was tentatively approved. In 1921, the city entered into a three-year contract with the Berlin Transport Propaganda GmbH.

After strong criticism from the citizens and the directorate of the trams, which advertised on the exterior as "speckled and striped monsters", the city took over the jurisdiction from 1925 and decided in 1927 to vote in interior tram advertisements, giving companies the opportunity to advertise on the inside of the trams and that the exterior should be left alone.

As a result, another form of vehicle advertising was established in 1930.[90] Companies were able to hire out-of-the-way wagons in order to disguise them completely with advertising boards and ordered them to go through the city without passengers. The first customer of such a tram was the Sarrasani Circus. The National Socialists used these advertisements as a means of propaganda and labelled rail car 13 with the slogan "We're going to England!"[90]

Lord Mayor Wolfgang Hoffman introduced the advertising on side-mounted roof-mounted signs in 1949 and announced that he would finance an additional bus service every year.[90] The colour scheme was set in brown font with an ivory-coloured base tone. Since then, roof plates have been installed on all vehicle generations up the GT8N series and are still used today as an advertising platform.

In 1964, the full marketing rights for advertising were transferred to Schiffmann & Co GmbH, a sister company of the advertising centre Lloyd, which was the first time there was advertising on the body's exterior surface.

After the GT8Ks were procured in 1981, the company also introduced a red and white colour scheme, which replaced the cream-coloured design with green trim strips. The new varnishing was based on the colours of Freiburg's coat of arms. Gradually, the older vehicles were repainted.

On 26 March 1994, the first vehicles were equipped with wrap advertising and partly glued window surfaces for the start-up of the route towards Munzinger Straße.[90] Up to 25% of the window surface area could be allocated to advertising.[91]

The Combinos are predominantly painted in red. There are white stripes between the driver cabins above and below the windows for the Combino Basics, while the Combino Advanced models have a black stripe, with a white stripe over it and white doors.

In 2011, GT8N 225 was painted to give it a more modern look. Some characteristics of the new design are the light grey base and the red "VAG tail". The tram remained in one place and the painting was partly removed for a whole advertisement.

While the GT8Zs were being renovated, since October 2013, several trams of this series have been given a new paint finish, which is based on the paintwork seen on the Urbos. The basic colours of red and white were kept and supplemented by black stripes.

Internal furnishing

[edit]The first series of two-axle railcars from 1901 could transport 31 passengers. Inside the tram there were two wooden horizontal benches that could accommodate 16 people. The large side windows could be darkened with curtains. The lighting and handrails for standing passengers were attached to the tram deck. In 1903, three matching side cars were put into operation. In contrast to previous vehicles, a conversion into an open salon carriage was possible. For this purpose, the glass panes framed with bronze could be completely put into the parapet.

The next generation of trams, delivered in 1907 numbered 38–40, had cross-sections with leather covers in the 2+1 scheme. In addition, the new trailers were equipped with foldable arm rests and spring-loaded padding.

The multi-purpose trams, the Sputnik articulate trams, and the two-way GT4 were fitted with seats made from Durofol. In contrast, the used trams from Stuttgart were equipped with artificial leather seats.

The seating in the Sputniks, obtained in 1959, originally faced the direction of travel.

The first two GT8 series had seats made of plastic, while trams purchased since 1990 were equipped with fabric upholstery, which only includes the seat surface for the GT8N; the rear surfaces were padded.

-

GT8K

-

GT8N

-

GT8Z

-

GT8Z after being redesigned

-

LCD screens detailing journey information in GT8Z 243

-

Combino Basic

-

Urbos

Depots

[edit]

West (VAG-Zentrum)

[edit]The western depot at Besançonallee was built in the 1970s. Initially, the 100,000 square metre site served exclusively as a depot for buses, but was taken over by the tram network. After the line between Bissierstraße and Haid opened in 1994, the western depot connected to the network. Today, all the workshops and administration conducted by the VAG are located at this site next to large storage areas for buses and trams. The depot, which used to offer space for 50 vehicles, had 17 new bays in 2015 to create additional capacities for the Urbos.[92]

South (Urachstraße/Lorettostraße)

[edit]The southern depot in Wiehre has existed since 1901 and was until 1994 one of the two regular depots for the network. It is located on Urachstraße close to the stop for Lorettostraße. The construction of the depot was not included in the building contract of the network, but was taken over the municipal building authority. The art nouveau buildings were expanded in 1907 and 1908 around a rear house and an intermediate building. The car hall, which was initially designed for 35 vehicles, was supplemented by a further storage hall, so that 77 vehicles could be stationed after it was converted.

After the second building opened at the northern depot, only five course cars and buses served the depot. After the new western depot was connecting to the network in 1994, the depot lost he last remaining regular scheduled services. At the present time, vehicles of the Freunde der Freiburger Straßenbahn are accommodated in the western and older part of the depot. The eastern hall now serves the local fire brigade.

North (Komturstraße)

[edit]

As a result of the continuous expansion of the fleet due to greater usage, the southern depot reached its full capacity limit in the 1920s. For this reason, a new depot at Komturstraße began operation in 1928 with the opening of the section Rennweg-Komturplatz. The five-track hall offered space for 30 two-axle trams. From then on, a large proportion of new trams were delivered to the northern depot, since the depot was better connected to the road and rail network compared to the southern depot. The embankment to the railway station was also nearby. Moreover, with its two-sided driveway – unlike the depot at Urachstraße – it could accommodate equipment vehicles. On 15 April 1950, the second storage unit was put into operation, which could accommodate 48 additional two-axle vehicles.

After the western depot opened, the northern depot lost its importance. Until 2006, the GT8K was left in the storage rooms before the building was demolished in 2007 to allow for residential development of the site.[93]

Track storage (Kaiserstuhlstraße)

[edit]At the beginning of the 1920s, a track storage area was put into operation at Kaiserstuhlstraße near to the Güterbahnhof. This was connected to the network at Neulindenstraße which was built during the Second World War for lazaretto transportation. The company stationed work vehicles on site and kept a scrap yard where carriages were dismantled. In the 1980s, the yard was closed down and railway connections dismantled.[94]

Planning

[edit]Medium-term plans

[edit]Gundelfingen line

[edit]The route to Gundelfingen was part of the project "Stadtbahn to northern Freiburg's districts and Gundelfingen". The route was going to cross the Alte Bundestraße and run towards the terminus loop at Waldstraße.[95] At the same time, it was planned to move Gundelfingen S-Bahn station 100 m to the north, in order to link the tram to the S-Bahn.

In April 2014, representatives of the CDU and the Greens in Gundelfingen launched a cross-party public opinion poll about further development of the tramway.[96] An immediate extension was planned for a station up to Auf der Höhe to better connect the local senior centres and the centre of Gundelfingen.[97] In a referendum in Gundelfingen on November 12, 2023, 58% of voters rejected a resumption of planning with a turnout of 61%.[98][99]

Planned tram network after 2020

[edit]In the 2007 transport development plan, the following network was proposed after the opening of all routes planned in the medium term:[100]

| Line | Route |

|---|---|

| 1 | Laßbergstraße – Schwabentorbrücke – Bertoldsbrunnen – Hauptbahnhof – Runzmattenweg – Moosweiher |