Murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner

| Murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |

| |

| Location | Neshoba County, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Date | June 21, 1964 |

Attack type | Triple-murder by shooting, white supremacist terrorism |

| Victims | |

| Perpetrators | White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan |

| Motive | White supremacy |

| Accused |

|

| Convicted |

|

| Convictions | Killen: Manslaughter (3 counts) Remaining convicted: Conspiracy against rights |

| Sentence |

|

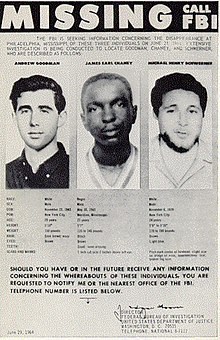

On June 21, 1964, three Civil Rights Movement activists, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, were murdered by local members of the Ku Klux Klan. They had been arrested earlier in the day for speeding, and after being released were followed by local law enforcement & others, all affiliated with the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.[1] After being followed for some time they were abducted by the group, brought to a secluded location, and shot. They were then buried in an earthen dam. All three were associated with the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) and its member organization, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). They had been working with the Freedom Summer campaign by attempting to register African Americans in Mississippi to vote. Since 1890 and through the turn of the century, Southern states had systematically disenfranchised most black voters by discrimination in voter registration and voting.

Chaney was African American, and Goodman and Schwerner were both Jewish. The three men had traveled roughly 38 miles (61 km) north from Meridian, to the community of Longdale, Mississippi, to talk with congregation members at a black church that had been burned; the church had been a center of community organization. The disappearance of the three men was initially investigated as a missing persons case. The civil-rights workers' burnt-out car was found parked near a swamp three days after their disappearance.[2][3] An extensive search of the area was conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), local and state authorities, and 400 U.S. Navy sailors.[4] Their bodies were not discovered until seven weeks later, when the team received a tip. During the investigation it emerged that members of the local White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the Neshoba County Sheriff's Office, and the Philadelphia, Mississippi Police Department were involved in the incident.[1]

The murder of the activists sparked national outrage and an extensive federal investigation, filed as Mississippi Burning (MIBURN), which later became the title of a 1988 film loosely based on the events. In 1967, after the state government refused to prosecute, the United States federal government charged 18 individuals with civil rights violations. Seven were convicted and another pleaded guilty, and received relatively minor sentences for their actions. Outrage over the activists' murder helped gain passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Forty-one years after the murders took place, one perpetrator, Edgar Ray Killen, was charged by the state of Mississippi for his part in the crimes. In 2005 he was convicted of three counts of manslaughter and was given a 60-year sentence.[5] On June 20, 2016, federal and state authorities officially closed the case. Killen died in prison in January 2018.

Background

[edit]In the early 1960s, the state of Mississippi, as well as other local and state governments in the American South, defied federal direction regarding racial integration.[6][7] Recent Supreme Court rulings had upset the Mississippi establishment, and white Mississippian society responded with open hostility. White supremacists used tactics such as bombings, murders, vandalism, and intimidation in order to discourage black Mississippians and their supporters from the Northern and Western states. In 1961, Freedom Riders, who challenged the segregation of interstate buses and related facilities, were attacked on their route. In September 1962, the University of Mississippi riots had occurred in order to prevent James Meredith from enrolling at the school.

The White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, a Ku Klux Klan splinter group based in Mississippi, was founded and led by Samuel Bowers of Laurel. As the summer of 1964 approached, white Mississippians prepared for what they perceived was an invasion from the north and west. College students had been recruited in order to aid local activists who were conducting grassroots community organizing, voter registration education and drives in the state. Media reports exaggerated the number of youths expected.[8] One Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) representative is quoted as saying that nearly 30,000 individuals would visit Mississippi during the summer.[8] Such reports had a "jarring impact" on white Mississippians and many responded by joining the White Knights.[8]

In 1890, Mississippi had passed a new constitution, supported by additional laws, which effectively excluded most black Mississippians from registering or voting. This status quo had long been enforced by economic boycotts and violence. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) wanted to address this problem by setting up Freedom Schools and starting voting registration drives in the state. Freedom schools were established in order to educate, encourage, and register the disenfranchised black citizens.[9] CORE members James Chaney, from Mississippi, and Michael Schwerner, from New York City, intended to set up a Freedom School for black people in Neshoba County to try to prepare them to pass the comprehension and literacy tests required by the state.

Registering others to vote

[edit]On Memorial Day, May 25, 1964, Schwerner and Chaney spoke to the congregation at Mount Zion Methodist Church in Longdale, Mississippi about setting up a Freedom School.[10] Schwerner implored the congregation to register to vote, saying, “you have been slaves too long, we can help you help yourselves”.[10] The White Knights learned of Schwerner’s voting drive in Neshoba County and soon developed a plot to hinder and ultimately destroy their work. They wanted to lure CORE workers into Neshoba County, so they assaulted congregants and torched the church, burning it to the ground.

On June 21, 1964, Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner met at the Meridian COFO headquarters before traveling to Longdale to investigate the burning of Mount Zion Church. Schwerner told COFO Meridian to search for them if they were not back by 4 p.m.; he said, “if we're not back by then, start trying to locate us.”[9]

Arrest

[edit]After visiting Longdale, the three civil rights workers decided not to take Road 491 to return to Meridian.[9] The narrow country road was unpaved; abandoned buildings littered the roadside. They decided to head west on Highway 16 to Philadelphia, the seat of Neshoba County, then take southbound Highway 19 to Meridian, figuring it would be the faster route. The time was approaching 3 p.m., and they were to be in Meridian by 4 p.m.

The CORE station wagon had barely passed the Philadelphia city limits when one of its tires went flat, and Deputy Sheriff Cecil Ray Price turned on his dashboard-mounted red light and followed them.[9] The trio stopped near the Beacon and Main Street fork. With a long radio antenna mounted to his patrol car, Price called for Officers Harry Jackson Wiggs and Earl Robert Poe of the Mississippi Highway Patrol.[9] Chaney was arrested for driving 65 mph in a 35 mph zone; Goodman and Schwerner were held for investigation. They were taken to the Neshoba County jail on Myrtle Street, a block from the courthouse.

In the Meridian office, workers became alarmed when the 4 p.m. deadline passed without word from the three activists. By 4:45 p.m., they notified the COFO Jackson office that the trio had not returned from Neshoba County.[9] The CORE workers called area authorities but did not learn anything; the contacted offices said they had not seen the three civil rights workers.[9]

The conspiracy

[edit]

Nine men, including Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence A. Rainey, were later identified as parties to the conspiracy to murder Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner.[11] Rainey denied he was ever a part of the conspiracy, but he was accused of ignoring the racially motivated offenses committed in Neshoba County. At the time of the murders, the 41-year-old Rainey insisted he was visiting his sick wife in a Meridian hospital and was later with family watching Bonanza.[12] As events unfolded, Rainey became emboldened with his newly found popularity in the Philadelphia community. Known for his tobacco chewing habit, Rainey was photographed and quoted in Life magazine: "Hey, let's have some Red Man", as other members of the conspiracy laughed while waiting for an arraignment to start.[13]

Fifty-year-old Bernard Akin had a mobile home business which he operated out of Meridian; he was a member of the White Knights.[11] Seventy-one-year-old Other N. Burkes, who usually went by the nickname of Otha, was a 25-year veteran of the Philadelphia Police. At the time of the December 1964 arraignment, Burkes was awaiting an indictment for a different civil rights case. Olen L. Burrage, who was 34 at the time, owned a trucking company. Burrage was developing a cattle farm which he called the Old Jolly Farm, where the three civil rights workers were found buried. Burrage, a former U.S. Marine who was honorably discharged, was quoted as saying: "I got a dam big enough to hold a hundred of them."[14] Several weeks after the murders, Burrage told the FBI: "I want people to know I'm sorry it happened."[15] Edgar Ray Killen, a 39-year-old Baptist preacher and sawmill owner, was convicted decades later of orchestrating the murders.

Frank J. Herndon, 46, operated a Meridian drive-in restaurant called the Longhorn;[11] he was the Exalted Grand Cyclops of the Meridian White Knights. James T. Harris, also known as Pete, was a White Knights investigator. The 30-year-old Harris was keeping tabs on the three civil rights workers' every move. Oliver R. Warner, 54, known as Pops, was a Meridian grocery owner and member of the White Knights. Herman Tucker lived in Hope, Mississippi, a few miles from the Neshoba County Fair grounds. Tucker, 36, was not a member of the White Knights; he was a building contractor who worked for Burrage. The White Knights gave Tucker the assignment of getting rid of the CORE station wagon driven by the workers. White Knights Imperial Wizard Samuel H. Bowers, who served with the U.S. Navy during World War II, was not apprehended on December 4, 1964, but he was implicated the following year. Bowers, then 39, was credited with saying: "This is a war between the Klan and the FBI. And in a war, there have to be some who suffer."[16]

On Sunday, June 7, 1964, nearly 300 White Knights met near Raleigh, Mississippi.[17] Bowers addressed the White Knights about what he described as a "nigger-communist invasion of Mississippi" that he expected to take place in a few weeks, in what CORE had announced as Freedom Summer.[17] The men listened as Bowers said: "This summer the enemy will launch his final push for victory in Mississippi", and, "there must be a secondary group of our members, standing back from the main area of conflict, armed and ready to move. It must be an extremely swift, extremely violent, hit-and-run group."[17]

Although federal authorities believed many others took part in the Neshoba County lynching, only 10 men were charged with the physical murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.[18] One of these was Deputy Sheriff Price, 26, who played a crucial role in implementing the conspiracy. Before his friend Rainey was elected sheriff in 1963, Price worked as a salesman, fireman, and bouncer.[18] Price, who had no prior experience in local law enforcement, was the only person who witnessed the entire event. He arrested the three men, released them the night of the murders, and chased them down state Highway 19 toward Meridian, eventually re-capturing them at the intersection near House, Mississippi. Price and the other nine men escorted them north along Highway 19 to Rock Cut Road, where they forced a stop and murdered the three civil rights workers.

Killen went to Meridian earlier that Sunday to organize and recruit men for the job to be carried out in Neshoba County.[19] Before the men left for Philadelphia, Travis M. Barnette, 36, went to his Meridian home to take care of a sick family member. Barnette owned a Meridian garage and was a member of the White Knights. Alton W. Roberts, 26, was a dishonorably discharged U.S. Marine who worked as a salesman in Meridian. Roberts, standing 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) and weighing 270 lb (120 kg), was physically formidable and renowned for his short temper. According to witnesses, Roberts shot both Goodman and Schwerner at point blank range, then shot Chaney in the head after another accomplice, James Jordan, shot him in the abdomen. Roberts asked, "Are you that nigger lover?" to Schwerner, and shot him after the latter responded, "Sir, I know just how you feel."[20] Jimmy K. Arledge, 27, and Jimmy Snowden, 31, were both Meridian commercial drivers. Arledge, a high school drop-out, and Snowden, a U.S. Army veteran, were present during the murders.

Jerry M. Sharpe, Billy W. Posey, and Jimmy L. Townsend were all from Philadelphia. Sharpe, 21, ran a pulp wood supply house. Posey, 28, a Williamsville automobile mechanic, owned a 1958 red and white Chevrolet; the car was considered fast and was chosen over Sharpe's. The youngest was Townsend, 17; he left high school in 1964 to work at Posey's Phillips 66 garage. Horace D. Barnette, 25, was Travis' younger half-brother; he had a 1957 two-toned blue Ford Fairlane sedan.[18] Horace's car is the one the group took after Posey's car broke down. Officials say that James Jordan, 38, killed Chaney. He confessed his crimes to the federal authorities in exchange for a plea deal.

Murders

[edit]After Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner's release from the Neshoba County jail shortly after 10 p.m. on June 21,[21] they were followed almost immediately by Deputy Sheriff Price in his 1957 white Chevrolet sedan patrol car.[22] Soon afterward, the civil rights workers left the city limits located along Hospital Road and headed south on Highway 19. The workers arrived at Pilgrim's store, where they might have been inclined to stop and use the telephone, but the presence of a Mississippi Highway Patrol car, manned by Officers Wiggs and Poe, most likely dissuaded them. They continued south toward Meridian.

The lynch mob members, who were in Barnette's and Posey's cars, were drinking while arguing who would kill the three young men. Eventually, Burkes drove up to Barnette's car and told the group: "They're going on 19 toward Meridian. Follow them!" After a quick rendezvous with Philadelphia Police officer Richard Willis, Price began pursuing the three civil rights workers in his police car.

Posey's Chevrolet carried Roberts, Sharpe, and Townsend. The Chevy apparently had carburetor problems, and was forced to the side of the highway. Sharpe and Townsend were ordered to stay with Posey's car and service it. Roberts transferred to Barnette's car, joining Arledge, Jordan, Posey, and Snowden.[23]

Price eventually caught the CORE station wagon heading west toward Union, on Road 492. Soon he stopped them and escorted the three civil rights workers north on Highway 19, back in the direction of Philadelphia. The caravan turned west on County Road 515 (also known as Rock Cut Road), and stopped at the secluded intersection of County Road 515 and County Road 284 (32°39′40.45″N 89°2′4.13″W / 32.6612361°N 89.0344806°W). The three men were subsequently shot by Jordan and Roberts.

Disposing of the evidence

[edit]

After the victims had been shot, they were quickly loaded into their station wagon and transported to Burrage's Old Jolly Farm, located along Highway 21, a few miles southwest of Philadelphia where an earthen dam for a farm pond was under construction.[24] Tucker was already at the dam waiting for the lynch mob's arrival. Earlier in the day, Burrage, Posey, and Tucker had met at either Posey's gas station or Burrage's garage to discuss these burial details, and Tucker most likely was the one who covered up the bodies using a bulldozer that he owned. An autopsy of Goodman, showing fragments of red clay in his lungs and grasped in his fists, suggests he was probably buried alive alongside the already dead Chaney and Schwerner.[25]

After all three were buried, Price told the group:

Well, boys, you've done a good job. You've struck a blow for the white man. Mississippi can be proud of you. You've let those agitating outsiders know where this state stands. Go home now and forget it. But before you go, I'm looking each one of you in the eye and telling you this: The first man who talks is dead! If anybody who knows anything about this ever opens his mouth to any outsider about it, then the rest of us are going to kill him just as dead as we killed those three sonofbitches [sic] tonight. Does everybody understand what I'm saying? The man who talks is dead, dead, dead![26]

Eventually, Tucker was tasked with disposing of the CORE station wagon in Alabama. For reasons unknown, the station wagon was left near a river in northeast Neshoba County along Highway 21. It was soon set ablaze and abandoned.[citation needed]

Investigation and public attention

[edit]

Unconvinced by the assurances of the Memphis-based agents, Sullivan elected to wait in Memphis ... for the start of the "invasion" of northern students ... Sullivan's instinctive decision to stick around Memphis proved correct. Early Monday morning, June 22, he was informed of the disappearance ... he was ordered to Meridian. The town would be his home for the next nine months.

— Cagin & Dray, We Are Not Afraid, 1988[27]

After reluctance from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to get directly involved, President Lyndon Johnson convinced him by threatening to send ex-CIA director Allen Dulles in his stead.[28] Hoover initially ordered the FBI Office in Meridian, run by John Proctor, to begin a preliminary search after the three men were reported missing. That evening, U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy escalated the search and ordered 150 federal agents to be sent from New Orleans.[29] Two local Native Americans found the smoldering car that evening; by the next morning, that information had been communicated to Proctor. Joseph Sullivan of the FBI immediately went to the scene.[30] By the next day, the federal government had arranged for hundreds of sailors from the nearby Naval Air Station Meridian to search the swamps of Bogue Chitto.

During the investigation, searchers including Navy divers and FBI agents discovered the bodies of Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore in the area (the first was found by a fisherman). They were college students who had disappeared in May 1964. Federal searchers also discovered 14-year-old Herbert Oarsby, and the bodies of five other deceased African Americans who were never identified.[31]

The disappearance of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner captured national attention. By the end of the first week, all major news networks were covering their disappearances. President Lyndon Johnson met with the parents of Goodman and Schwerner in the Oval Office. Walter Cronkite's broadcast of the CBS Evening News on June 25, 1964, called the disappearances "the focus of the whole country's concern".[32] The FBI eventually offered a $25,000 reward (equivalent to $253,000 in 2024), which led to the breakthrough in the case. Meanwhile, Mississippi officials resented the outside attention. Sheriff Rainey said, "They're just hiding and trying to cause a lot of bad publicity for this part of the state." Mississippi Governor Paul B. Johnson Jr. dismissed concerns, saying the young men "could be in Cuba".[33]

The bodies of the CORE activists were found only after an informant (discussed in FBI reports only as "Mr. X") passed along a tip to federal authorities.[34] They were discovered on August 4, 1964, 44 days after their murder, underneath an earthen dam on Burrage's farm. Schwerner and Goodman had each been shot once in the heart; Chaney, a black man, had been severely beaten, castrated and shot three times. The identity of "Mr. X" was revealed publicly forty years after the original events, and revealed to be Maynard King, a Mississippi Highway Patrol officer close to the head of the FBI investigation. King died in 1966.[35][36]

In the summer of 1964, according to Linda Schiro and other sources, FBI field agents in Mississippi recruited the mafia captain Gregory Scarpa to help them find the missing civil rights workers.[37] The FBI was convinced the three men had been murdered, but could not find their bodies. The agents thought that Scarpa, using illegal interrogation techniques not available to agents, might succeed at gaining this information from suspects. Once Scarpa arrived in Mississippi, local agents allegedly provided him with a gun and money to pay for information. Scarpa and an agent allegedly pistol-whipped and kidnapped Lawrence Byrd, a TV salesman and secret Klansman, from his store in Laurel and took him to Camp Shelby, a local Army base. At Shelby, Scarpa severely beat Byrd and stuck a gun barrel down his throat. Byrd finally revealed to Scarpa the location of the three men's bodies.[38][39] The FBI has never officially confirmed the Scarpa story. Though not necessarily contradicting the claim of Scarpa's involvement in the matter, investigative journalist Jerry Mitchell and Illinois high school teacher Barry Bradford claimed that Mississippi highway patrolman Maynard King provided the grave locations to FBI agent Joseph Sullivan after obtaining the information from an anonymous third party. In January 1966, Scarpa allegedly helped the FBI a second time in Mississippi on the murder case of Vernon Dahmer, killed in a fire set by the Klan. After this second trip, Scarpa and the FBI had a sharp disagreement about his reward for these services. The FBI then dropped Scarpa as a confidential informant.[40]

I blame the people in Washington DC and on down in the state of Mississippi just as much as I blame those who pulled the trigger. ... I'm tired of that! Another thing that makes me even tireder though, that is the fact that we as people here in the state and the country are allowing it to continue to happen. ... Your work is just beginning. If you go back home and sit down and take what these white men in Mississippi are doing to us. ... if you take it and don't do something about it. ... then God damn your souls![31][41]

This and the Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965 contributed to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which Johnson signed on August 6 of that year.

Malcolm X used the delayed resolution of the case in his argument that the federal government was not protecting black lives, and African Americans would have to defend themselves: "And the FBI head, Hoover, admits that they know who did it, they've known ever since it happened, and they've done nothing about it. Civil rights bill down the drain."[42][43]

By late November 1964 the FBI accused 21 Mississippi men of engineering a conspiracy to injure, oppress, threaten, and intimidate Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner. Most of the suspects were apprehended by the FBI on December 4, 1964.[44] The FBI detained the following individuals: B. Akin, E. Akin, Arledge, T. Barnette, Bowers, Burkes, Burrage, Harris, Herndon, Killen, Posey, Price, Rainey, Roberts, Sharpe, Snowden, Townsend, Tucker, and Warner. Two individuals who were not interviewed and photographed, H. Barnette and James Jordan, would later confess their roles during the murder.[45]

Because Mississippi officials refused to prosecute the killers for murder, a state crime, the federal government, led by prosecutor John Doar, charged 18 individuals under 18 U.S.C. §242 and §371 with conspiring to deprive the three activists of their civil rights (by murder). They indicted Sheriff Rainey, Deputy Sheriff Price and 16 other men. A U. S. Commissioner dismissed the charges six days later, declaring that the confession on which the arrests were based was hearsay. One month later, government attorneys secured indictments against the conspirators from a federal grand jury in Jackson. On February 24, 1965, however, Federal Judge William Harold Cox, an ardent segregationist, threw out the indictments against all conspirators other than Rainey and Price on the ground that the other seventeen were not acting "under color of state law." In March 1966, the United States Supreme Court overruled Cox and reinstated the indictments. Defense attorneys then made the argument that the original indictments were flawed because the pool of jurors from which the grand jury was drawn contained insufficient numbers of minorities. Rather than attempt to refute the charge, the government summoned a new grand jury and, on February 28, 1967, won reindictments.[46]

1967 federal trial

[edit]Trial in the case of United States v. Cecil Price, et al., began on October 7, 1967, in the Meridian courtroom of Judge William Harold Cox. A jury of seven white men and five white women was selected. Defense attorneys exercised peremptory challenges against all seventeen potential black jurors. A white man, who admitted under questioning by Robert Hauberg, the U.S. Attorney for Mississippi, that he had been a member of the KKK "a couple of years ago," was challenged for cause, but Cox denied the challenge.

The trial was marked by frequent crises. Star prosecution witness James Jordan cracked under the pressure of anonymous death threats made against him and had to be hospitalized at one point. The jury deadlocked on its decision and Judge Cox employed the "Allen charge" to bring them to resolution. Seven defendants, mostly from Lauderdale County, were convicted. The convictions in the case represented the first-ever convictions in Mississippi for the killing of a civil rights worker.[46]

Those found guilty on October 20, 1967, were Cecil Price, Klan Imperial Wizard Samuel Bowers, Alton Wayne Roberts, Jimmy Snowden, Billy Wayne Posey, Horace Barnette, and Jimmy Arledge. Sentences ranged from three to ten years. After exhausting their appeals, the seven began serving their sentences in March 1970. None served more than six years. Sheriff Rainey was among those acquitted. Two of the defendants, E.G. Barnett, a candidate for sheriff, and Edgar Ray Killen, a local minister, had been strongly implicated in the murders by witnesses, but the jury came to a deadlock on their charges and the federal prosecutor decided not to retry them.[29] On May 7, 2000, the jury revealed that in the case of Killen, they deadlocked after a lone juror stated she "could never convict a preacher".[47]

Further research and 2005 murder trial

[edit]

"To many it will always be June 21, 1964, in Philadelphia."

— Cagin & Dray, We Are Not Afraid, 1988[48]

For much of the next four decades, no legal action was taken regarding the murders. In 1989, on the 25th anniversary of the murders, the U.S. Congress passed a non-binding resolution honoring the three men; Senator Trent Lott and the rest of the Mississippi delegation refused to vote for it.[49]

The journalist Jerry Mitchell, an award-winning investigative reporter for Jackson's The Clarion-Ledger, wrote extensively about the case for six years. In the late 20th century, Mitchell had earned fame by his investigations that helped secure convictions in several other high-profile Civil Rights Era murder cases, including the murders of Medgar Evers and Vernon Dahmer, and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham.

In the case of the civil rights workers, Mitchell was aided in developing new evidence, finding new witnesses, and pressuring the state to take action by Barry Bradford,[50] a high school teacher at Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, Illinois, and three of his students, Allison Nichols, Sarah Siegel, and Brittany Saltiel. Bradford later achieved recognition for helping Mitchell clear the name of Clyde Kennard.[51]

Together the student-teacher team produced a documentary for the National History Day contest. It presented important new evidence and compelling reasons to reopen the case. Bradford also obtained an interview with Edgar Ray Killen, which helped convince the state to investigate. Partially by using evidence developed by Bradford, Mitchell was able to determine the identity of "Mr. X", the mystery informer who had helped the FBI discover the bodies and end the conspiracy of the Klan in 1964.[52]

Mitchell's investigation and the high school students' work in creating Congressional pressure, national media attention and Bradford's taped conversation with Killen prompted action.[53] In 2004, on the 40th anniversary of the murders, a multi-ethnic group of citizens in Philadelphia, Mississippi, issued a call for justice. More than 1,500 people, including civil rights leaders and Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour, joined them to support having the case re-opened.[54][55]

On January 6, 2005, a Neshoba County grand jury indicted Edgar Ray Killen on three counts of murder. When the Mississippi Attorney General prosecuted the case, it was the first time the state had taken action against the perpetrators of the murders. Rita Bender, Michael Schwerner's widow, testified in the trial.[56] On June 21, 2005, a jury convicted Killen on three counts of manslaughter; he was described as the man who planned and directed the killing of the civil rights workers.[57] Killen, then 80 years old, was sentenced to three consecutive terms of 20 years in prison. His appeal, in which he claimed that no jury of his peers would have convicted him in 1964 based on the evidence presented, was rejected by the Supreme Court of Mississippi in 2007.[58]

On June 20, 2016, Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood and Vanita Gupta, top prosecutor for the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Justice Department, said the investigation had ended but would be taken up again if new information was received.[59]

Legacy and honors

[edit]Individual

[edit]

See:

United States Congress

[edit]The murders contributed to congressional passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and other federal and state civil rights legislation.[60][61][62][63]

National

[edit]- Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were posthumously awarded the 2014 Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama.

Ohio

[edit]- Miami University's now-defunct Western Program included historical lectures about Freedom Summer and the events of the massacre.[citation needed]

- There is a memorial on the Western campus of Miami University. It includes dozen of headlines about the murder, and plaques honoring and detailing the victims' life and work.

- Additionally, Miami's board of trustees voted unanimously in 2019 to name the lounges of three residence halls on the Western campus after Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.[64]

Michigan

[edit]- At Cedar Springs High School in Cedar Springs, Michigan, an outdoor memorial theatre is dedicated to the Freedom Summer alums. The day of Goodman's murder is acknowledged each year on campus, and the clock tower of the campus library is dedicated to Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner.[citation needed]

Mississippi

[edit]

- A stone memorial at the Mt. Nebo Baptist Church commemorates the three civil rights activists.[65]

- Several Mississippi State Historical Markers have been erected relating to this incident:

- Freedom Summer Murders (1989), near Mount Zion United Methodist Church in Neshoba County[66][67]

- Goodman, Cheney, and Schwerner Murder Site (2008, later vandalized and rededicated in 2013), at the intersection of MS 19 and County Road 515[67]

- Old Neshoba County Jail (2012), at the site where the trio were held, on the north side of East Myrtle Street, between Byrd and Center Avenues[67]

New York

[edit]- The Chaney-Goodman-Schwerner Clock Tower of Queens College's Rosenthal Library was built in 1988 and dedicated in 1989.[68] There is a photograph of the plaque Archived April 17, 2021, at the Wayback Machine on the Queens College website.

- New York City named "Freedom Place", a four-block stretch in Manhattan's Upper West Side, in honor of Chaney, Goodman, and Shwerner.[when?] A plaque on 70th Street and Freedom Place (Riverside Drive) briefly tells their story.[69][70] The plaque was re-located in 1999 to the garden of Hostelling International New York. Mrs. Goodman wanted the plaque to be in a place visited by young people.[citation needed]

- A stained glass window depicting the three was placed in Sage Chapel at Cornell University in 1991. Schwerner was a Cornell graduate, as were Goodman's parents.[71]

- In June 2014, Schwerner's hometown, Pelham, New York, kicked off a year-long, town-wide commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner's deaths:[72]

- On June 22, 2014, the Pelham Picture House held a free screening of the film Freedom Summer ahead of the film's June 24 premiere on American Experience on PBS. The screening was followed by a discussion and Q&A session with an expert panel.[73]

- In November, close to Election Day and Schwerner's birthday, the Schwerner-Chaney-Goodman Memorial Commemoration Committee and the Pelham School District will host a multiple activities, such as a keynote speech by Nicholas Lemann (Dean Emeritus and Henry R. Luce professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in New York City).[72]

- Also in autumn 2014, The Picture House Evening Film Club for students in grades 9 through 12 will show a film they are creating, on the theme "What price freedom", inspired by Schwerner's commitment and sacrifice.[72]

In culture

[edit]Numerous works portray or refer to the stories of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, the aftermath of their murders and subsequent trial, and other related events of that summer.

Film

[edit]- In the 27-minute documentary short, Summer in Mississippi (1964 Canada, 1965 U.S.), written and directed by Beryl Fox

- The two-part CBS made-for-television movie, Attack on Terror: The FBI vs. the Ku Klux Klan (1975), co-starring Wayne Rogers and Ned Beatty, is based on Don Whitehead's book (Attack on Terror: The F.B.I. Against the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi). Actor Hilly Hicks portrayed "Charles Gilmore", a fictionalized representation of James Chaney, actor Andrew Parks portrayed "Steven Bronson", a fictionalized representation of Andrew Goodman, and actor Peter Strauss portrayed "Ben Jacobs", a fictionalized representation of Schwerner. The sympathetic portrayal of FBI agents in Attack on Terror: The FBI vs. the Ku Klux Klan (1974) and Mississippi Burning (1988) angered civil rights activists, who believed that the Bureau received too much credit for solving the case and too little condemnation for its previous lack of action in regards to civil rights abuses.[citation needed]

- The feature film Mississippi Burning (1988), starring Willem Dafoe and Gene Hackman, is loosely based on the murders and the ensuing FBI investigation. Goodman is portrayed in the film by actor Rick Zieff and is simply identified as "Passenger". Schwerner, simply identified in the credits as "Goatee", is portrayed in the film by Geoffrey Nauffts.

- The television movie Murder in Mississippi (1990) examines the events leading up to the deaths of the activists. In this film, Blair Underwood portrays Chaney; Josh Charles portrays Goodman; and Tom Hulce portrays Schwerner. Royce D. Applegate portrays a character named "Deputy Winter", who is an obvious stand in for Cecil Price.

- The documentary Neshoba (2008) details the murders, the investigation, and the 2005 trial of Edgar Ray Killen. The film features statements by many surviving relatives of the victims, other residents of Neshoba county, and other people connected to the civil rights movement, as well as footage from the 2005 trial.[74]

- The TV movie, All the Way (HBO, 2016) about the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidency depicted through the 1964 Civil Rights agenda, evokes the implication of the Johnson administration in the investigation around these murders.

Art

[edit]- Norman Rockwell depicted the murders in his painting, Murder in Mississippi (1965), to illustrate Charles Morgan's investigative article in Look, titled Southern Justice (June 29, 1965). The article was part of a series on civil rights.[75][76]

Literature

[edit]- The economists Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis dedicated their book A Cooperative Species (2011) to Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner.

- In Stephen King's The Dark Tower VI: Song of Susannah (2005), the protagonist Susannah Dean (Odetta) reminisces about her time in Mississippi as a civil rights activist, when she met Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in Oxford Town. She thinks about making love to James Chaney and singing the song, "Man of Constant Sorrow".

- George Oppen dedicated his poem, "The Book of Job and a Draft of a Poem to Praise the Paths of the Living" (1973), to Schwerner.

- Alice Walker's novel Meridian (1976) portrays issues of the civil rights era.

- Donald E. Westlake dedicated his novel Put a Lid on It (2002) to Schwerner.

- Don Whitehead's nonfiction book, Attack on Terror: The F.B.I. Against the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi (1970), details the events a week before the assassinations and concludes with the Federal trial of the conspirators. The book was adapted as a two-part television movie in 1975.

- Howard Cruse's graphic novel Stuck Rubber Baby (1995) deals with issues of the civil rights era. After a stare down with a policeman, the protagonist recalls the murders of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner and reflects on the "price that can get exacted when you look bigotry too squarely in the eye" (p. 201).

- David J Dennis Jr's (in collaboration with David J Dennis Sr) non-fiction book The Movement Made Us (2022) describes the events unfolding in chapter XIII Vote

Theatre

[edit]- April 2024 the play Three Mothers had its world premiere at Capital Repertory Theatre in Albany NY. The play, written by Ajene D. Washington, offers a potential glimpse into the conversations that the mothers of the men who were murdered might have had. Its inspiration is based on the photograph of the women leaving the final funeral of their boys.

Music

[edit]Concert drama

[edit]- Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Steven Stucky's evening-long concert drama, August 4, 1964, was based on the events of that date: the discovery of the bodies of the three civil rights workers and the reported attack on two American warships in the Gulf of Tonkin. Commissioned to commemorate the centennial of the birth of Lyndon B. Johnson, it premiered to excellent reviews.[77]

Songs

[edit]- Music researcher Dr. Justin Brummer, founding editor of the Vietnam War Song Project and the Post-War American Political Songs Project, has identified 17+ songs related to the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.

- Richard Fariña's song, "Michael, Andrew and James", performed with Mimi Fariña, was included in their first Vanguard album, Celebrations for a Grey Day (1965).

- Tom Paxton included the tribute song, "Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney" on his Ain't That News (1965) album.

- Pete Seeger and Frances Taylor wrote the song, "Those Three are On My Mind", about the murders, to commemorate the three workers.[78]

- Phil Ochs wrote his song, "Here's to the State of Mississippi", about these events and other violations of civil rights that took place in that state.

- Although it was written a year before the murders, Simon & Garfunkel's song, "He Was My Brother" from Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M. (1964), has become associated with Andrew Goodman, who attended Queens College near the end of Simon's years at the school. Simon may have known Goodman only slightly, but they shared many friends.[citation needed]

- The band Flobots' song, "Same Thing", asks to bring back Chaney.

- The Vietnam War Song Project has identified the song "Eve of Tomorrow" by Tony Mammarella, an answer to Barry McGuire's Eve of Destruction, which contains the line: "Why did the three kids come from the north, they didn't have to join in the fight, but they marched down to Mississippi and they died for what they knew was right"

- The Vietnam War Song Project also notes that the Phil Ochs song "Days of Decision" contains the line: "From the three bodies buried in the Mississippi mud".

Television

[edit]- In the Dark Skies episode "We Shall Overcome". It aired December 14, 1996.

- The FBI Files discussed this case in its final episode of season 1, entitled "The True Story of Mississippi Burning". It aired February 23, 1999.

- The story was a backdrop in at least two first season episodes of the television series American Dreams (2002): "Down the Shore" and "High Hopes".

- In the Law & Order episode "Chosen", defense lawyer Randy Dworkin (played by Peter Jacobson) prefaces a speech against affirmative action with the phrase, "Janeane Garofalo herself can storm into my office and tear down the framed photos of Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner, that I keep on the wall over my desk ..."[79] In a Season 3 episode the case is also referenced.

- The murder was among the 10 events that were shown on the History Channel's 10 Days That Unexpectedly Changed America miniseries in April 2006.

- In Mad Men: "Public Relations" (season 4, episode 1), Don Draper's date Bethany mentions knowing Andrew Goodman, stating "The world is so dark right now" and "Is that what it takes to make things change?" These statements are the first indication of what year season 4 takes place in.[citation needed]

- Referenced as backdrop news reports in American Dreams season 1, episodes 21, "Fear Itself", and 24, "High Hopes".

- All the Way, a 2016 HBO film, briefly portrays the kidnapping and murders, and portrays the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in their aftermath.

Audio

[edit]- Season 3 of the CBC podcast, Someone Knows Something, revolves around the discovery in July 1964 of the bodies of Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore, African-American men who had been murdered two months earlier by the Klan, while the FBI was searching for the bodies of the three missing civil rights workers.[80]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ 60 years in prison

References

[edit]- ^ a b "General Article: Murder in Mississippi". American Experience. PBS. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ^ ""Mississippi Burning" murders". CBS News. June 19, 2014. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ Bayless, Les (May 25, 1996). "Three who gave their lives: Remembering the martyrs of Mississippi Freedom Summer, 1964". People's Weekly World. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ "We're Stymied, Rights Search Leaders Admit". The Desert Sun. No. 283. UPI. July 1, 1964. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ "Former Klansman found guilty of manslaughter". CNN. June 22, 2005. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ "State of Siege: Mississippi Whites and the Civil Rights Movement – American RadioWorks". Americanradioworks.publicradio.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ "New York Times Chronology (September 1962) - John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum". Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c Whitehead, Don (September 1970). "Murder in Mississippi". Reader's Digest: 196.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). "June 21, 1964". We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books. p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). "June 21, 1964". We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books.[page needed]

- ^ Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). "Rock Cut Road". We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books. p. 282.

- ^ Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). "The Forty-Four Days". We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books. pp. 377–378.

- ^ Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). "Rock Cut Road". We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books. p. 283.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (March 19, 2013). "Olen Burrage Dies at 82; Linked to Killings in 1964". The New York Times.

- ^ Whitehead, Don (1970). Attack on Terror: The FBI Against the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi. Funk & Wagnalls. p. 233. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c Whitehead, Don (September 1970). "Murder in Mississippi". Reader's Digest: 194.

- ^ a b c Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books.[page needed]

- ^ Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). "Rock Cut Road". We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books. p. 278.

- ^ Kotz, Nick (2005). Judgment Days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Laws that Changed America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-618-08825-6. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "Klansman who Orchestrated Mississippi Burning Killings Dies in Prison". The Clarion Ledger. January 12, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). "Rock Cut Road". We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books. pp. 285–286.

- ^ "'Mississippi Burning' Defendant Dead at 82". Akron Beacon Journal. March 17, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ "Missing Trio Found". The Delta Democrat-Times. August 5, 1964. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ "A Mississippi Freedom Summer Pilgrimage: An Atrocity We Must Never Forget". The Huffington Post. July 25, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ Ball, Howard (2004). "COFO's Mississippi 'Freedom Summer' Project". Murder in Mississippi. University Press of Kansas. p. 62.

- ^ Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). "A Problem of Law Enforcement". We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books. p. 329.

- ^ Farber, David (1994). The Age of Great Dreams: America in the 1960s. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 94.

- ^ a b "Neshoba Murders Case – A Chronology". Arkansas Delta Truth and Justice Center. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. "The Mississippi Burning Trial". Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Lynching of Chaney, Schwerner & Goodman ~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

- ^ Ball, Howard (2004). "COFO's Mississippi 'Freedom Summer' Project". Murder in Mississippi. University Press of Kansas. p. 64.

- ^ "Civil Rights: Grim Discovery in Mississippi". Time. June 22, 2005. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Whitehead, Don (September 1970). "Murder in Mississippi". Reader's Digest: 214.

- ^ "Who Is Mr X In The Mississippi Burning Case?". Speaking For A Change. September 2, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ Moorer, Mickel (2019). Documents identifying whistle-blower. By Jerry Mitchell, December 2, 2007, The Clarion-Ledger, Jackson MS. FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1525554926.

- ^ "Mob moll says Mafiosi helped FBI". Yahoo!. October 29, 2007. Archived from the original on November 1, 2007.

- ^ Danne, Fredric. "The G-man and the Hit Man" New Yorker Magazine, December 16, 1996.

- ^ "Mob Solved 'Mississippi Burning' Murders?" ABC News

- ^ "GREG SCARPA SNR. Part Two". Mafia-International.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ "The Eulogy – American Experience – PBS". Pbs.org. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ "Malcolm X in Oxford, Archive on 4 – BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Saladin Ambar, Malcolm X at Oxford Union: Racial Politics in a Global Era (Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 178

- ^ Nevin, David (December 1964). "Day of Accusation in Mississippi". Life. pp. 36–37.

- ^ Linder, Douglas O. (2012). "Mississippi Burning Trial: A Chronology". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ a b Linder, Douglas O. "The Mississippi Burning Trial (United States vs. Price et al.): A Trial Account". law2.umkc.edu. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Mitchell, Jerry (February 4, 2014). "Congressional honor sought for Freedom Summer martyrs". USA Today. Retrieved February 11, 2014 – via The (Jackson, Miss.) Clarion-Ledger.

- ^ Cagin, Seth; Philip Dray (1988). "Raise America Up". We Are Not Afraid. Bantam Books. p. 454.

- ^ Ladd, Donna (May 29, 2007). "Dredging Up the Past: Why Mississippians Must Tell Our Own Stories". Jackson Free Press. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ Bradford, Barry (September 2, 2012). "The Mississippi Burning Case Reopened – Today Show". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ "Home Page – Public & Motivational Speaker Barry Bradford". Speaking For A Change. Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Mitchell, Jerry (December 2, 2007). "Documents Identify Whistle-blower", The Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, MS).

- ^ "How Mississippi Burning Was Reopened". MississippiBurning.org. Archived from the original on September 24, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Broder, David S. (January 16, 2005). "Mississippi Healing". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Statement Asking for Justice in the June 21, 1964, Murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner" Archived February 16, 2019, at the Wayback Machine,The Neshoba Democrat. June 24, 2004. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ^ Dewan, Shaila (June 17, 2005). "Widow Recalls Ghosts of '64 at Rights Trial". The New York Times. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Dewan, Shaila (June 22, 2005). "Ex-Klansman Guilty of Manslaughter in 1964 Deaths". The New York Times. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "Mississippi: Convictions Upheld". The New York Times. Associated Press. April 13, 2007. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Amy, Jeff (June 20, 2016). "Prosecutor: 'Mississippi Burning' Civil Rights Case Closed". Associated Press. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ Hayes, Sister Jan (October 29, 2020). "Fighting Voter Suppression: Living the Legacy of Mississippi Burning 56 Years Later". Sisters of Mercy. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ "Mississippi Burning". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ "The Presidential Recordings: Lyndon B. Johnson". Texas Monthly. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ Kornbluth, Jesse (July 23, 1989). "The Struggle Continues". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 24, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ "Miami names rooms for slain Freedom Summer activists". Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ "Roots of Struggle" (PDF). Neshoba Justice. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ File:Mt. Zion Methodist Churchstate history marker in Neshoba County (alternate view).JPG

- ^ a b c "Neshoba County". Mississippi Historical Markers. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ "Dedication of the Library Clock Tower IN MEMORY OF JAMES CHANEY, ANDREW GOODMAN & MICHAEL SCHWERNER." Program of dedication ceremony for Queens College clock tower, May 10, 1989, Queens College Department of Special Collections and Archives (New York, NY).

- ^ Kingson Bloom, Jennifer (October 30, 1994). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: UPPER WEST SIDE; Residents Shrinking as Freedom Place Is Slowly Sinking". The New York Times.

- ^ "The story behind a little-known West Side street". Ephemeral New York. April 24, 2009.

- ^ "Chimes concert to honor Schwerner, Chaney, Goodman". Cornell Chronicle. June 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c Cole, Amy (June 20, 2014). "Free Screening of Freedom Summer at The Picture House". ArtsWestchester. Westchester Arts Council.

- ^ "Screening of "Freedom Summer" At The Picture House on June 22". The Pelhams-PLUS. June 11, 2014. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ Harvey, Dennis (November 4, 2008). "Neshoba". Variety. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "Norman Rockwell: Murder in Mississippi (June 14 – August 31, 2014; The Donna and Jim Barksdale Galleries for Changing Exhibitions)". Mississippi Museum of Art. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ Esaak, Shelley. "Murder in Mississippi (Southern Justice), 1965". About.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ^ Oestreich, James R. (September 20, 2008). "All the Way Through Fateful Day for L.B.J." The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Seeger, Pete. "Those Three Are on My Mind". Pete Seeger Appreciation Page. Archived from the original on October 15, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- ^ "Law & Order: 'Chosen'". TV.com. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009.

- ^ "Someone Knows Something". CBC. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Mississippi Burning, by Joel Norst. New American Library, 1988. ISBN 978-0-451-16049-2

- The "Mississippi Burning" Civil Rights Murder Conspiracy Trial: A Headline Court Case, by Harvey Fireside. Enslow Publishers, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7660-1762-7

- The Mississippi Burning Trial: A Primary Source Account, by Bill Scheppler. The Rosen Publishing Group, 2003. ISBN 978-0-8239-3972-5

- Murder in Mississippi: United States v. Price and the Struggle for Civil Rights, by Howard Ball. University Press of Kansas, 2004. ISBN 978-0-70061-315-1

- Three Lives for Mississippi, by William Bradford Huie. University Press of Mississippi, 1965. ISBN 978-1-57806-247-8

- "Untold Story of the Mississippi Murders", by William Bradford Huie, Saturday Evening Post September 5, 1964, No. 30, pp 11–15

- We Are Not Afraid: The Story of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney and the Civil Rights Campaign for Mississippi, by Seth Cagin and Philip Dray. Bantam Books, 1988. ISBN 0-553-35252-0

- Witness in Philadelphia, by Florence Mars. Louisiana State University Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0-8071-0265-7

External links

[edit]- Murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner

- 1964 in Mississippi

- 1964 murders in the United States

- Antisemitic attacks and incidents in the United States

- Crimes adapted into films

- Events of the civil rights movement

- Deaths by firearm in Mississippi

- Deaths by person in Mississippi

- Jewish-American lynching victims

- June 1964 in the United States

- Ku Klux Klan crimes in Mississippi

- Lynching deaths in Mississippi

- Murders by law enforcement officers in the United States

- Neshoba County, Mississippi

- Police brutality in the United States

- Mass murder in the United States in the 1960s

- Racially motivated violence against African Americans

- Terrorist incidents in the United States in 1964

- Trios

- Violence against men in the United States

- History of voting rights in the United States

- Assassinations in the United States

- Mass murder in 1964

- Evidence tampering

- Arson in the United States

- Arson in the 1960s

- African American–Jewish relations