Berry Washington

Berry Washington | |

|---|---|

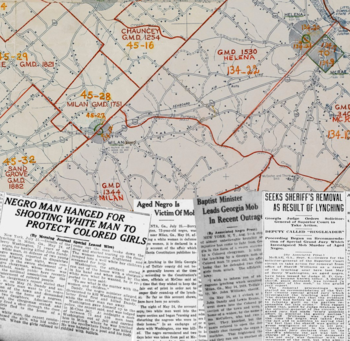

News Coverage of Berry Washington Lynching over Milan, Georgia Map | |

| Born | c. 1847 |

| Died | 2:00AM May 26, 1919 (72 years old) |

| Body discovered | Milan, Georgia |

Berry Washington (c. 1847 – May 26, 1919) was a 72-year-old black man who was lynched in Milan, Georgia, in 1919. He was in jail after killing a white man who was attacking two young girls. He was taken from jail and lynched by a mob.

History

[edit]At 1:00 am on the morning of May 24, 1919, two white men, John Dowdy and Levi Evans, went into the black section of Milan. They first tried to get into the home of Emma McCollers who had two young daughters.[1] When the family refused to open the door Dowdy fired his gun. This caused the girls to flee to another house, the home of widow Emma Tisber. The two men followed and invaded the Tisber home and attempted to assault two young black girls.[1] When the two girls attempted to hide under the porch, Dowdy and Evans began ripping up the floor to get to them.[2] Washington, a black man, attempted to defend the girls and get the men to leave. Dowdy fired at Washington and after a struggle, Washington, who was 72 years old, shot and killed Dowdy , "He fell with his pistol in his right hand and a cigarette in the other, and a flask of liquor fell out of his pocket."[1]

Washington went uptown and woke up the chief of police, Mr. Stuckey, who sent Washington to the McRae jail at 2:00 am May 24, 1919. There he stayed in jail until the 25th, at 12 o’clock, when a crowd of white men, led by a Baptist minister,[3][1] removed Washington from the jail. To possibly hide their crimes all black residents of Milan were rounded up and ordered out of the town on the night of May 25th.[1] At 2:00 am on May 26 the lynch mob hung him from a post and shot him repeatedly until his body fell in pieces from the post. White residents rioted in the city, damaging and burning many black homes. They threatened black citizens, lest they dare to speak out about the events in public.[4][5]

Local authorities attempted to cover up the incident, but a local preacher, Reverend Judson Dinkins, sent a letter to Monroe Work at the Tuskegee Institute, who in turn passed the letter to John Shillady of the NAACP. When Governor of Georgia Hugh Dorsey (term 1917–1921) became aware of the incident, he offered a $1,000 reward for the arrest and conviction of the mob.[6] [7] Dr. Floyd McRae offered an additional $500 reward, for a total of $1,500 ($26,400 in 2025).[8] Although the perpetrators were well known in the community, no one claimed the reward, and no one was ever charged for the murder.[9] Washington's corpse was left there for a full day.[10]

In September 1919, it was reported that Georgia Judge E. D. Graham ordered the city of McRae, Georgia, to take action and possibly remove Sheriff Williams as a result of the lynching. It was also alleged that one of the McRae deputies was a ringleader in the killing.[11]

Aftermath

[edit]This was not the only incident of racial violence in Georgia in 1919. There were a number of riots, some of which are listed below:

| Date | Place | Event | Death toll | Property Damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 8 | Blakeley, Georgia | Race Riot | 4 killed | |

| April 13-15 | Jenkins County, Georgia | Race Riot | 6 killed | 3 black Masonic lodges and 7 black churches burned down |

| May 10 | Sylvester, Georgia | Race Riot | 1 killed | |

| May 27–29 | Putnam County, Georgia | Arson attack | 2 black Masonic lodges and 5 black churches burned down | |

| July 6 | Dublin, Georgia | Black protection group prevents lynching | ||

| August 27-29 | Laurens County, Georgia | Race Riot | 1 killed | 1 black Masonic lodges and 3 black churches burned down |

These race riots were one of several incidents of civil unrest that began in the so-called American Red Summer of 1919. Terrorist attacks on black communities and white oppression in over three dozen cities and counties. In most cases, white mobs attacked African American neighborhoods. In some cases, black community groups resisted the attacks, especially in Chicago and Washington, D.C. Most deaths occurred in rural areas during events like the Elaine Race Riot in Arkansas, where an estimated 100 to 240 black people and 5 white people were killed. Also in 1919 were the Chicago Race Riot and Washington D.C. race riot which killed 38 and 39 people respectively. Both had many more non-fatal injuries and extensive property damage reaching into the millions of dollars.[12]

Bibliography

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b c d e Phoenix Tribune 1919, p. 1.

- ^ Albuquerque Morning Journal 1919, p. 1.

- ^ Cayton's Weekly 1919, p. 3.

- ^ McWhirter 2011, p. 52.

- ^ Atlanta Constitution 1919.

- ^ The Pensacola Journal 1919, p. 1.

- ^ Richmond Times-Dispatch 1919, p. 1.

- ^ New-York Tribune 1919, p. 10.

- ^ Voogd 2008, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Cayton's Weekly 1919, p. 2.

- ^ Richmond Times-Dispatch 1919a, p. 1.

- ^ The New York Times 1919.

References

- Albuquerque Morning Journal (July 26, 1919). "Negro Man Hanged for Shooting White Man to Protect Colored Girls". Albuquerque Morning Journal. Albuquerque, New Mexico: Democrat Pub. Co. pp. 1–8. ISSN 2375-5903. OCLC 11221430. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- Atlanta Constitution (July 27, 1919). "Rewards Offered In Lynching Case". Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia: Howell Family. ISSN 2473-1609. OCLC 8821030.

- Cayton's Weekly (September 20, 1919). "Georgia's Shame". Cayton's Weekly. Seattle, Washington: Horace R. Cayton Sr. pp. 1–4. ISSN 2158-4699. OCLC 17248379. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- McWhirter, Cameron (2011). Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9780805089066. - Total pages: 368

- The New York Times (October 5, 1919). "For Action on Race Riot Peril". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- New-York Tribune (July 27, 1919). "$1,500 Posted for Arrest of Lynchers of Negro". New-York Tribune. New York. pp. 1–78. ISSN 1941-0646. OCLC 9405688. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- The Pensacola Journal (July 27, 1919). "Large Reward is Offered to Find Lynchers". The Pensacola Journal. Pensacola, Florida: M. Loftin. pp. 1–24. ISSN 1941-109X. OCLC 16280864. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- Phoenix Tribune (August 2, 1919). "Baptist Minister Leads Georgia Mob In Recent Outrage". Phoenix Tribune. Phoenix, Arizonz: Arthur Randolph Smith. pp. 1–4. OCLC 35642959. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- Richmond Times-Dispatch (July 27, 1919). "Governor offers reward for apprenshenion of mob". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia: Times Dispatch Pub. Co. pp. 1–52. ISSN 2333-7761. OCLC 9493729. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- Richmond Times-Dispatch (September 7, 1919a). "Sheriff's Removal as Result of Lynching". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia: Times Dispatch Pub. Co. pp. 1–52. ISSN 2333-7761. OCLC 9493729. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- Voogd, Jan (2008). Race Riots and Resistance: The Red Summer of 1919. Peter Lang. ISBN 9781433100673. - Total pages: 234

- 1840s births

- 1919 deaths

- 1919 murders in the United States

- Deaths by firearm in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Lynching deaths in Georgia (U.S. state)

- People from Dodge County, Georgia

- People from Telfair County, Georgia

- People murdered in Georgia (U.S. state)

- 1919 crimes in the United States

- 1919 in Christianity

- 1919 in Georgia (U.S. state)

- 1919 riots in the United States

- May 1919

- Jenkins County, Georgia

- African-American history of Georgia (U.S. state)

- Arson in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Riots and civil disorder in Georgia (U.S. state)

- White American riots in the United States

- Red Summer

- History of Georgia (U.S. state)

- Crimes against police officers in the United States

- Attacks on African-American churches

- History of Baptists