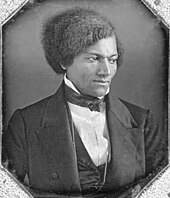

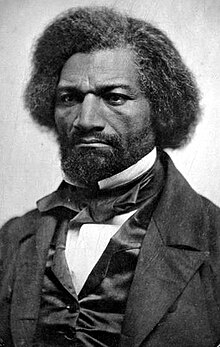

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass | |

|---|---|

Douglass in 1879 | |

| United States Minister Resident to Haiti | |

| In office November 14, 1889 – July 30, 1891 | |

| Appointed by | Benjamin Harrison |

| Preceded by | John E. W. Thompson |

| Succeeded by | John S. Durham |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey c. February 14, 1818 Cordova, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died | February 20, 1895 (aged 77–78) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Hope Cemetery, Rochester, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | |

| Relatives | Douglass family |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, c. February 14, 1818[a] – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He became the most important leader of the movement for African-American civil rights in the 19th century.

After escaping from slavery in Maryland in 1838, Douglass became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York and gained fame for his oratory[4] and incisive antislavery writings. Accordingly, he was described by abolitionists in his time as a living counterexample to claims by supporters of slavery that enslaved people lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens.[5] Northerners at the time found it hard to believe that such a great orator had once been enslaved. It was in response to this disbelief that Douglass wrote his first autobiography.[6]

Douglass wrote three autobiographies, describing his experiences as an enslaved person in his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), which became a bestseller and was influential in promoting the cause of abolition, as was his second book, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855). Following the Civil War, Douglass was an active campaigner for the rights of freed slaves and wrote his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. First published in 1881 and revised in 1892, three years before his death, the book covers his life up to those dates. Douglass also actively supported women's suffrage, and he held several public offices. Without his knowledge or consent, Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States, as the running mate of Victoria Woodhull on the Equal Rights Party ticket.[7]

Douglass believed in dialogue and in making alliances across racial and ideological divides, as well as, after breaking with William Lloyd Garrison, in the anti-slavery interpretation of the U.S. Constitution.[8] When radical abolitionists, under the motto "No Union with Slaveholders", criticized Douglass's willingness to engage in dialogue with slave owners, he replied: "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong."[9]

Early life and slavery

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay in Talbot County, Maryland. The plantation was between Hillsboro and Cordova;[10] his birthplace was likely his grandmother's cabin[b] east of Tappers Corner and west of Tuckahoe Creek.[11][12][13] In his first autobiography, Douglass stated: "I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it."[14] In successive autobiographies, he gave more precise estimates of when he was born, his final estimate being 1817.[10] However, based on the extant records of Douglass's former owner, Aaron Anthony, historian Dickson J. Preston determined that Douglass was born in February 1818.[2] Though the exact date of his birth is unknown, he chose to celebrate February 14 as his birthday, remembering that his mother called him her "Little Valentine."[1][15]

Birth family

Douglass's mother, enslaved, was of African descent and his father, who may have been her master, apparently of European descent;[16] in his Narrative (1845), Douglass wrote: "My father was a white man."[10] According to David W. Blight's 2018 biography of Douglass, "For the rest of his life he searched in vain for the name of his true father."[17] Douglass's genetic heritage likely also included Native American.[18] Douglass said his mother Harriet Bailey gave him his name Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey and, after he escaped to the North in September 1838, he took the surname Douglass, having already dropped his two middle names.[19]

He later wrote of his earliest times with his mother:[20]

The opinion was also whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion, I know nothing. ... My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant. ... It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age. ... I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone.

After separation from his mother during infancy, young Frederick lived with his maternal grandmother Betsy Bailey, who was also enslaved, and his maternal grandfather Isaac, who was free.[21] Betsy would live until 1849.[22] Frederick's mother remained on the plantation about 12 miles (19 km) away, visiting Frederick only a few times before her death when he was 7 years old.

Returning much later, about 1883, to purchase land in Talbot County that was meaningful to him, he was invited to address "a colored school":

I once knew a little colored boy whose mother and father died when he was six years old. He was a slave and had no one to care for him. He slept on a dirt floor in a hovel, and in cold weather would crawl into a meal bag head foremost and leave his feet in the ashes to keep them warm. Often he would roast an ear of corn and eat it to satisfy his hunger, and many times has he crawled under the barn or stable and secured eggs, which he would roast in the fire and eat.

That boy did not wear pants like you do, but a tow linen shirt. Schools were unknown to him, and he learned to spell from an old Webster's spelling-book and to read and write from posters on cellar and barn doors, while boys and men would help him. He would then preach and speak, and soon became well known. He became Presidential Elector, United States Marshal, United States Recorder, United States diplomat, and accumulated some wealth. He wore broadcloth and didn't have to divide crumbs with the dogs under the table. That boy was Frederick Douglass.[23]

Early learning and experience

The Auld family

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

At the age of 6, Douglass was separated from his grandparents and moved to the Wye House plantation, where Aaron Anthony worked as overseer[13] and Edward Lloyd was his unofficial master.[24] After Anthony died in 1826, Douglass was given to Lucretia Auld, wife of Thomas Auld, who sent him to serve Thomas's brother Hugh Auld and his wife Sophia Auld in Baltimore. From the day he arrived, Sophia saw to it that Douglass was properly fed and clothed, and that he slept in a bed with sheets and a blanket.[25] Douglass described her as a kind and tender-hearted woman, who treated him "as she supposed one human being ought to treat another."[26] Douglass felt that he was lucky to be in the city, where he said enslaved people were almost freemen, compared to those on plantations.

When Douglass was about 12, Sophia Auld began teaching him the alphabet. Hugh Auld disapproved of the tutoring, feeling that literacy would encourage enslaved people to desire freedom. Douglass later referred to this as the "first decidedly antislavery lecture" he had ever heard. "'Very well, thought I,'" wrote Douglass. "'Knowledge unfits a child to be a slave.' I instinctively assented to the proposition, and from that moment I understood the direct pathway from slavery to freedom."[27]

Under her husband's influence, Sophia came to believe that education and slavery were incompatible and one day snatched a newspaper away from Douglass.[28] She stopped teaching him altogether and hid all potential reading materials, including her Bible, from him.[25] In his autobiography, Douglass related how he learned to read from white children in the neighborhood and by observing the writings of the men with whom he worked.[29]

Douglass continued, secretly, to teach himself to read and write. He later often said, "knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom."[30] As Douglass began to read newspapers, pamphlets, political materials, and books of every description, this new realm of thought led him to question and condemn the institution of slavery. In later years, Douglass credited The Columbian Orator, an anthology that he discovered at about age 12, with clarifying and defining his views on freedom and human rights. First published in 1797, the book is a classroom reader, containing essays, speeches, and dialogues, to assist students in learning reading and grammar. He later learned that his mother had also been literate, about which he would later declare:

I am quite willing, and even happy, to attribute any love of letters I possess, and for which I have got—despite of prejudices—only too much credit, not to my admitted Anglo-Saxon paternity, but to the native genius of my sable, unprotected, and uncultivated mother—a woman, who belonged to a race whose mental endowments it is, at present, fashionable to hold in disparagement and contempt.[31]

William Freeland

When Douglass was hired out to William Freeland, he "gathered eventually more than thirty male slaves on Sundays, and sometimes even on weeknights, in a Sabbath literacy school."[32]

Edward Covey

In 1833, Thomas Auld took Douglass back from Hugh ("[a]s a means of punishing Hugh," Douglass later wrote). Thomas sent Douglass to work for Edward Covey, a poor farmer who had a reputation as a "slave-breaker". He whipped Douglass so frequently that his wounds had little time to heal. Douglass later said the frequent whippings broke his body, soul, and spirit.[33] The 16-year-old Douglass finally rebelled against the beatings, however, and fought back. After Douglass won a physical confrontation, Covey never tried to beat him again.[34][35]

Recounting his beatings at Covey's farm in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Douglass described himself as "a man transformed into a brute!"[36] Still, Douglass came to see his physical fight with Covey as life-transforming, and introduced the story in his autobiography as such: "You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man."[37]

Escape from slavery

Douglass first tried to escape from Freeland, who had hired him from his owner, but was unsuccessful. In 1837, Douglass met and fell in love with Anna Murray, a free black woman in Baltimore about five years his senior. Her free status strengthened his belief in the possibility of gaining his own freedom. Murray encouraged him and supported his efforts by aid and money.[38]

On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped by boarding a northbound train of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad in Baltimore.[39] The area where he boarded was formerly thought to be a short distance east of the train depot, in a recently developed neighborhood between the modern neighborhoods of Harbor East and Little Italy. This depot was at President and Fleet Streets, east of "The Basin" of the Baltimore harbor, on the northwest branch of the Patapsco River. Research cited in 2021, however, suggests that Douglass in fact boarded the train at the Canton Depot of the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad on Boston Street, in the Canton neighborhood of Baltimore, further east.[40][41][42]

Douglass reached Havre de Grace, Maryland, in Harford County, in the northeast corner of the state, along the southwest shore of the Susquehanna River, which flowed into the Chesapeake Bay. Although this placed him only some 20 miles (32 km) from the Maryland–Pennsylvania state line, it was easier to continue by rail through Delaware, another slave state. Dressed in a sailor's uniform provided to him by Murray, who also gave him part of her savings to cover his travel costs, he carried identification papers and protection papers that he had obtained from a free black seaman.[38][43][44]

Douglass crossed the wide Susquehanna River by the railroad's steam-ferry at Havre de Grace to Perryville on the opposite shore, in Cecil County, then continued by train across the state line to Wilmington, Delaware, a large port at the head of the Delaware Bay. From there, because the rail line was not yet completed, he went by steamboat along the Delaware River farther northeast to the "Quaker City" of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, an anti-slavery stronghold. He continued to the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles in New York City. His entire journey to freedom took less than 24 hours.[45] Douglass later wrote of his arrival in New York City:

I have often been asked, how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. And my readers may share the same curiosity. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the 'quick round of blood,' I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe. In a letter written to a friend soon after reaching New York, I said: 'I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.' Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.[46]

Once Douglass had arrived, he sent for Murray to follow him north to New York. She brought the basic supplies for them to set up a home. They were married on September 15, 1838, by a black Presbyterian minister, just eleven days after Douglass had reached New York.[45] At first they adopted Johnson as their married name, to divert attention.[38]

Religious views

As a child, Douglass was exposed to a number of religious sermons, and in his youth, he sometimes heard Sophia Auld reading the Bible. In time, he became interested in literacy; he began reading and copying bible verses, and he eventually converted to Christianity.[47][48] He described this approach in his last biography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass:

I was not more than thirteen years old when, in my loneliness and destitution, I longed for some one to whom I could go, as to a father and protector. The preaching of a white Methodist minister, named Hanson, was the means of causing me to feel that in God I had such a friend. He thought that all men, great and small, bond and free, were sinners in the sight of God: that they were but natural rebels against his government; and that they must repent of their sins, and be reconciled to God through Christ. I cannot say that I had a very distinct notion of what was required of me, but one thing I did know well: I was wretched and had no means of making myself otherwise. I consulted a good coloured man named Charles Lawson, and in tones of holy affection he told me to pray, and to "cast all my care upon God." This I sought to do; and though for weeks I was a poor, broken-hearted mourner, traveling through doubts and fears, I finally found my burden lightened, and my heart relieved. I loved all mankind, slaveholders not excepted, though I abhorred slavery more than ever. I saw the world in a new light, and my great concern was to have everybody converted. My desire to learn increased, and especially did I want a thorough acquaintance with the contents of the Bible.[49][50]

Douglass was mentored by Rev. Charles Lawson, and, early in his activism, he often included biblical allusions and religious metaphors in his speeches. Although a believer, he strongly criticized religious hypocrisy[51] and accused slaveholders of "wickedness", lack of morality, and failure to follow the Golden Rule. In this sense, Douglass distinguished between the "Christianity of Christ" and the "Christianity of America" and considered religious slaveholders and clergymen who defended slavery as the most brutal, sinful, and cynical of all who represented "wolves in sheep's clothing".[48][52]

In What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?, an oration Douglass gave in the Corinthian Hall of Rochester,[53] he sharply criticized the attitude of religious people who kept silent about slavery, and he charged that ministers committed a "blasphemy" when they taught it as sanctioned by religion. He considered that a law passed to support slavery was "one of the grossest infringements of Christian Liberty" and said that pro-slavery clergymen within the American Church "stripped the love of God of its beauty, and leave the throne of religion a huge, horrible, repulsive form", and "an abomination in the sight of God".[51]

Of ministers like John Chase Lord, Leonard Elijah Lathrop, Ichabod Spencer, and Orville Dewey, he said that they taught, against the Scriptures, that "we ought to obey man's law before the law of God". He further asserted, "in speaking of the American church, however, let it be distinctly understood that I mean the great mass of the religious organizations of our land. There are exceptions, and I thank God that there are. Noble men may be found, scattered all over these Northern States ... Henry Ward Beecher of Brooklyn, Samuel J. May of Syracuse, and my esteemed friend [Robert R. Raymonde]".[51]

He maintained that "upon these men lies the duty to inspire our ranks with high religious faith and zeal, and to cheer us on in the great mission of the slave's redemption from his chains". In addition, he called religious people to embrace abolitionism, stating, "let the religious press, the pulpit, the Sunday school, the conference meeting, the great ecclesiastical, missionary, Bible and tract associations of the land array their immense powers against slavery and slave-holding; and the whole system of crime and blood would be scattered to the winds."[51]

During his visits to the United Kingdom between 1846 and 1848, Douglass asked British Christians never to support American churches that permitted slavery,[54] and he expressed his happiness to know that a group of ministers in Belfast had refused to admit slaveholders as members of the Church.

On his return to the United States, Douglass founded the North Star, a weekly publication with the motto "Right is of no sex, Truth is of no color, God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren." In his 1848 "Letter to Thomas Auld", Douglass denounced his former slaveholder for leaving Douglass's family illiterate:

Your wickedness and cruelty committed in this respect on your fellow-creatures, are greater than all the stripes you have laid upon my back, or theirs. It is an outrage upon the soul—a war upon the immortal spirit, and one for which you must give account at the bar of our common Father and Creator.[55]

Sometimes considered a precursor of a non-denominational liberation theology,[56][57] Douglass was a deeply spiritual man, as his home continues to show. The fireplace mantle features busts of two of his favorite philosophers, David Friedrich Strauss, author of The Life of Jesus, and Ludwig Feuerbach, author of The Essence of Christianity. In addition to several Bibles and books about various religions in the library, images of angels and Jesus are displayed, as well as interior and exterior photographs of Washington's Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church.[58] Throughout his life, Douglass had linked that individual experience with social reform, and, according to John Stauffer, he, like other Christian abolitionists, followed practices such as abstaining from tobacco, alcohol and other substances that he believed corrupted body and soul.[59] Douglass stated himself that he was a teetotaler.[60] According to David W. Blight, however, "Douglass loved cigars" and received them as gifts from Ottilie Assing.[61]

Douglass praised the agnostic orator Robert G. Ingersoll, whom Douglass met in Peoria, Illinois, stating, "Genuine goodness is the same, whether found inside or outside the church, and that to be an 'infidel' no more proves a man to be selfish, mean and wicked than to be evangelical proves him to be honest, just and human. Perhaps there were Christian ministers and Christian families in Peoria at that time by whom I might have been received in the same gracious manner ... but in my former visits to this place I had failed to meet them".[62]

Family life

Douglass and Anna Murray had five children: Rosetta Douglass, Lewis Henry Douglass, Frederick Douglass Jr., Charles Remond Douglass, and Annie Douglass (died at the age of ten). Charles and Rosetta helped produce his newspapers.

Anna Douglass remained a loyal supporter of her husband's public work. His relationships with Julia Griffiths and Ottilie Assing, two women with whom he was professionally involved, caused recurring speculation and scandals.[63] Assing was a journalist recently immigrated from Germany, who first visited Douglass in 1856 seeking permission to translate My Bondage and My Freedom into German. Until 1872, she often stayed at his house "for several months at a time" as his "intellectual and emotional companion."[64]

Assing held Anna Douglass "in utter contempt" and was vainly hoping that Douglass would separate from his wife. Douglass biographer David W. Blight concludes that Assing and Douglass "were probably lovers".[64] Though Douglass and Assing are widely believed to have had an intimate relationship, the surviving correspondence contains no proof of such a relationship.[65]

Anna died in 1882. In 1884, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a white suffragist and abolitionist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was the daughter of Gideon Pitts Jr., an abolitionist colleague and friend of Douglass's. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College (then called Mount Holyoke Female Seminary), Pitts worked on a radical feminist publication named Alpha while living in Washington, D.C. She later worked as Douglass's secretary.[66]

Assing, who had depression and was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer, committed suicide in France in 1884 after hearing of the marriage.[67] Upon her death, Assing bequeathed Douglass a $13,000 trust fund (equivalent to $441,000 in 2023), a "large album", and his choice of books from her library.[68]

The marriage of Douglass and Pitts provoked a storm of controversy, since Pitts was both white and nearly 20 years younger. Many in her family stopped speaking to her; his children considered the marriage a repudiation of their mother. But feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton congratulated the couple.[69] Douglass responded to the criticisms by saying that his first marriage had been to someone the color of his mother, and his second to someone the color of his father.[70]

Career

Abolitionist and preacher

The couple settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts (an abolitionist center, full of former enslaved people), in 1838, moving to Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1841.[71] After meeting and staying with Nathan and Mary Johnson, they adopted Douglass as their married name.[38] Douglass had grown up using his mother's surname of Bailey; after escaping slavery he had changed his surname first to Stanley and then to Johnson. In New Bedford, the latter was such a common name that he wanted one that was more distinctive, and asked Nathan Johnson to choose a suitable surname. Nathan suggested "Douglass", after having read the poem The Lady of the Lake by Walter Scott, in which two of the principal characters have the surname "Douglas".[72][73]

Douglass thought of joining a white Methodist Church, but was disappointed, from the beginning, upon finding that it was segregated. Later, he joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, an independent black denomination first established in New York City, which counted among its members Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman.[74] He became a licensed preacher in 1839,[75] which helped him to hone his oratorical skills. He held various positions, including steward, Sunday-school superintendent, and sexton. In 1840, Douglass delivered a speech in Elmira, New York, then a station on the Underground Railroad, in which a black congregation would form years later, becoming the region's largest church by 1940.[58]

Douglass also joined several organizations in New Bedford and regularly attended abolitionist meetings. He subscribed to William Lloyd Garrison's weekly newspaper, The Liberator. He later said that "no face and form ever impressed me with such sentiments [of the hatred of slavery] as did those of William Lloyd Garrison." So deep was this influence that in his last autobiography, Douglass said "his paper took a place in my heart second only to The Bible."[76]

Garrison was likewise impressed with Douglass and had written about his anti-colonization stance in The Liberator as early as 1839. Douglass first heard Garrison speak in 1841, at a lecture that Garrison gave in Liberty Hall, New Bedford. At another meeting, Douglass was unexpectedly invited to speak. After telling his story, Douglass was encouraged to become an anti-slavery lecturer. A few days later, Douglass spoke at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual convention, in Nantucket. Then 23 years old, Douglass conquered his nervousness and gave an eloquent speech about his life as a slave.

While living in Lynn, Douglass engaged in an early protest against segregated transportation. In September 1841, at Lynn Central Square station, Douglass and his friend James N. Buffum were thrown off an Eastern Railroad train because Douglass refused to sit in the segregated railroad coach.[71][77][78][79]

In 1843, Douglass joined other speakers in the American Anti-Slavery Society's "Hundred Conventions" project, a six-month tour at meeting halls throughout the eastern and midwestern United States. During this tour, slavery supporters frequently accosted Douglass. At a lecture in Pendleton, Indiana, an angry mob chased and beat Douglass before a local Quaker family, the Hardys, rescued him. His hand was broken in the attack; it healed improperly and bothered him for the rest of his life.[80] A stone marker in Falls Park in the Pendleton Historic District commemorates this event.

In 1847, Douglass explained to Garrison, "I have no love for America, as such; I have no patriotism. I have no country. What country have I? The Institutions of this Country do not know me – do not recognize me as a man."[81]

Autobiography

Douglass's best-known work is his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, written during his time in Lynn, Massachusetts[82] and published in 1845. At the time, some skeptics questioned whether a black man could have produced such an eloquent piece of literature. The book received generally positive reviews and became an immediate bestseller. Within three years, it had been reprinted nine times, with 11,000 copies circulating in the United States. It was also translated into French and Dutch and published in Europe.

Douglass published three autobiographies during his lifetime (and revised the third of these), each time expanding on the previous one. The 1845 Narrative was his biggest seller and probably allowed him to raise the funds to gain his legal freedom the following year, as discussed below. In 1855, Douglass published My Bondage and My Freedom. In 1881, in his sixties, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he revised in 1892.

Travels to Ireland and Great Britain

Douglass's friends and mentors feared that the publicity would draw the attention of his ex-owner, Hugh Auld, who might try to get his "property" back. They encouraged Douglass to tour Ireland, as many former slaves had done. Douglass set sail on the Cambria for Liverpool, England, on August 16, 1845. He traveled in Ireland as the Great Famine was beginning.

The feeling of freedom from American racial discrimination amazed Douglass:[83]

Eleven days and a half gone, and I have crossed three thousand miles of the perilous deep. Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle [Ireland]. I breathe, and lo! the chattel [slave] becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab—I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door—I am shown into the same parlor—I dine at the same table—and no one is offended.... I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, 'We don't allow niggers in here!'

Still, Douglass was astounded by the extreme levels of poverty he encountered in Dublin, much of it reminding him of his experiences in slavery. In a letter to William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass wrote "I see much here to remind me of my former condition, and I confess I should be ashamed to lift up my voice against American slavery, but that I know the cause of humanity is one the world over. He who really and truly feels for the American slave, cannot steel his heart to the woes of others; and he who thinks himself an abolitionist, yet cannot enter into the wrongs of others, has yet to find a true foundation for his anti-slavery faith."[84]

He also met and befriended the Irish nationalist and strident abolitionist Daniel O'Connell,[85][86] who was to be a great inspiration.[87][88]

Douglass spent two years in Ireland and Great Britain, lecturing in churches and chapels. His draw was such that some facilities were "crowded to suffocation". One example was his hugely popular London Reception Speech, which Douglass delivered in May 1846 at Alexander Fletcher's Finsbury Chapel. Douglass remarked that in England he was treated not "as a color, but as a man".[89]

In 1846, Douglass met with Thomas Clarkson, one of the last living British abolitionists, who had persuaded Parliament to abolish slavery in Great Britain's colonies.[90] During this trip Douglass became legally free, as British supporters led by Anna Richardson and her sister-in-law Ellen of Newcastle upon Tyne raised funds to buy his freedom from his American owner Thomas Auld.[89][91] Many supporters tried to encourage Douglass to remain in England but, with his wife still in Massachusetts and three million of his black brethren in bondage in the United States, he returned to America in the spring of 1847,[89] soon after the death of Daniel O'Connell.[92]

In the 21st century, historical plaques were installed on buildings in Cork and Waterford, Ireland, and London to celebrate Douglass's visit: the first is on the Imperial Hotel in Cork and was unveiled on August 31, 2012; the second is on the façade of Waterford City Hall, unveiled on October 7, 2013. It commemorates his speech there on October 9, 1845.[93] The third plaque adorns Nell Gwynn House, South Kensington in London, at the site of an earlier house where Douglass stayed with the British abolitionist George Thompson.[94] On July 31, 2023, the first statue of him in Europe was unveiled in High Street in Belfast.[95]

Douglass spent time in Scotland and was appointed "Scotland's Antislavery agent."[96] He made anti-slavery speeches and wrote letters back to the US. He considered the city of Edinburgh to be elegant, grand and very welcoming. Maps of the places in the city that were important to his stay are held by the National Library of Scotland.[97][98] A plaque and a mural at 33 Gilmore Place in Edinburgh mark his stay there in 1846.

"A variety of collaborative projects are currently [in 2021] underway to commemorate Frederick Douglass's journey and visit to Ireland in the 19th century."[99]

Return to the United States; the abolitionist movement

After returning to the U.S. in 1847, using £500 (equivalent to $57,716 in 2023) given to him by English supporters,[89] Douglass started publishing his first abolitionist newspaper, the North Star, from the basement of the Memorial AME Zion Church in Rochester, New York.[100] Originally, Pittsburgh journalist Martin Delany was co-editor but Douglass didn't feel he brought in enough subscriptions, and they parted ways.[101][page needed] The North Star's motto was "Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren."[102] The AME Church and North Star joined in the freedmen community's vigorous opposition to the mostly white American Colonization Society and its proposal to send free black people to Africa. Douglass also participated in the Underground Railroad. He and his wife provided lodging and resources in their home to more than four hundred fugitive slaves.[102]

Douglass also soon split with Garrison, whom he found unwilling to support actions against American slavery.[103] Earlier Douglass had agreed with Garrison's position that the Constitution was pro-slavery, because of the Three-Fifths Clause, the compromise that provided that 60 percent of the number of enslaved people would be added to "the whole Number of free Persons"[104] for the purpose of apportioning congressional seats; and protection of the international slave trade through 1807. Garrison had burned copies of the Constitution to express his opinion. However, Lysander Spooner published The Unconstitutionality of Slavery (1846), which examined the United States Constitution as an antislavery document. Douglass's change of opinion about the Constitution and his splitting from Garrison around 1847 became one of the abolitionist movement's most notable divisions. Douglass angered Garrison by saying that the Constitution could and should be used as an instrument in the fight against slavery.[105]

On July 24, 1851, "shortly after his announced change of opinion", Douglass delivered a speech titled, "Is the United States Constitution For or Against Slavery".[106] He expressed his changed views again in an 1860 speech in Glasgow, Scotland, titled, "The Constitution of the United States: is it pro-slavery or anti-slavery?". In that speech, he said, "When I escaped from slavery, and was introduced to the Garrisonians, I adopted very many of their opinions.... I was young, had read but little, and naturally took some things on trust. Subsequent reading and experience", however, "brought me to other conclusions". He now believed that "dissolution of the American Union", which Garrison advocated, "would place the slave system more exclusively under the control of the slaveholding States...." In addition, "Mr. Garrison and his friends tell us that while in the Union we are responsible for slavery.... I deny that going out of the Union would free us from that responsibility.... The American people in the Northern States have helped to enslave the black people. Their duty will not be done till they give them back their plundered rights."[107]

Letter to his former owner

In September 1848, on the tenth anniversary of his escape, Douglass published an open letter addressed to his former master, Thomas Auld, berating him for his conduct, and inquiring after members of his family still held by Auld.[108][109] In the course of the letter, Douglass adeptly transitions from formal and restrained to familiar and then to impassioned. At one point he is the proud parent, describing his improved circumstances and the progress of his own four young children. But then he dramatically shifts tone:

Oh! sir, a slaveholder never appears to me so completely an agent of hell, as when I think of and look upon my dear children. It is then that my feelings rise above my control. ... The grim horrors of slavery rise in all their ghastly terror before me, the wails of millions pierce my heart, and chill my blood. I remember the chain, the gag, the bloody whip, the deathlike gloom overshadowing the broken spirit of the fettered bondman, the appalling liability of his being torn away from wife and children, and sold like a beast in the market.[55]

In a graphic passage, Douglass asked Auld how he would feel if Douglass had come to take away his daughter Amanda into slavery, treating her the way he and members of his family had been treated by Auld.[108][109] Yet in his conclusion Douglass shows his focus and benevolence, stating that he has "no malice towards him personally," and asserts that, "there is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for comfort, which I would not readily grant. Indeed, I should esteem it a privilege, to set you an example as to how mankind ought to treat each other."[55]

Women's rights

In 1848, Douglass was the only black person to attend the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, in upstate New York.[110][111] Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked the assembly to pass a resolution asking for women's suffrage.[112] Many of those present opposed the idea, including influential Quakers James and Lucretia Mott.[113] Douglass stood and spoke eloquently in favor of women's suffrage; he said that he could not accept the right to vote as a black man if women could also not claim that right. He suggested that the world would be a better place if women were involved in the political sphere:

In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.[113]

After Douglass's powerful words, the attendees passed the resolution.[113][114]

In the wake of the Seneca Falls Convention, Douglass used an editorial in The North Star to press the case for women's rights. He recalled the "marked ability and dignity" of the proceedings, and briefly conveyed several arguments of the convention and feminist thought at the time.

On the first count, Douglass acknowledged the "decorum" of the participants in the face of disagreement. In the remainder, he discussed the primary document that emerged from the conference, a Declaration of Sentiments, and the "infant" feminist cause. He criticized opponents of women's rights: "A discussion of the rights of animals would be regarded with far more complacency by many of what are called the wise and the good of our land, than would be a discussion of the rights of woman."[115] He also noted the link between abolitionism and feminism, the overlap between the communities.

His opinion as the editor of a prominent newspaper carried weight, and he stated the position of the North Star explicitly: "We hold woman to be justly entitled to all we claim for man." This letter, written a week after the convention, reaffirmed the first part of the paper's slogan, "right is of no sex."

After the Civil War, when the 15th Amendment giving black men the right to vote was being debated, Douglass split with the Stanton-led faction of the women's rights movement. Douglass supported the amendment, which would grant suffrage to black men. Stanton opposed the 15th Amendment because it limited the expansion of suffrage to black men; she predicted its passage would delay for decades the cause for women's right to vote. Stanton argued that American women and black men should band together to fight for universal suffrage, and opposed any bill that split the issues.[116] Douglass and Stanton both knew that there was not yet enough male support for women's right to vote, but that an amendment giving black men the vote could pass in the late 1860s. Stanton wanted to attach women's suffrage to that of black men so that her cause would be carried to success.[117]

Douglass thought such a strategy was too risky, that there was barely enough support for black men's suffrage. He feared that linking the cause of women's suffrage to that of black men would result in failure for both. Douglass argued that white women, already empowered by their social connections to fathers, husbands, and brothers, at least vicariously had the vote. Black women, he believed, would have the same degree of empowerment as white women once black men had the vote.[117] Douglass assured the American women that at no time had he ever argued against women's right to vote.[118]

Ideological refinement

In 1850, Douglass was elected the vice president of the American League of Colored Laborers, the first black labor union in the United States, which he had also helped found.[119] Meanwhile, in 1851, he merged the North Star with Gerrit Smith's Liberty Party paper to form Frederick Douglass' Paper,[120] which was published until 1859.[121]

On July 5, 1852, Douglass delivered an address in Corinthian Hall at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. This speech eventually became known as "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?"; one biographer called it "perhaps the greatest antislavery oration ever given."[122] In 1853, he was a prominent attendee of the radical abolitionist National African American Convention in Rochester. Douglass was one of five people whose names were attached to the address of the convention to the people of the United States published under the title, The Claims of Our Common Cause. The other four were Amos Noë Freeman, James Monroe Whitfield, Henry O. Wagoner, and George Boyer Vashon.[123]

Like many abolitionists, Douglass believed that education would be crucial for African Americans to improve their lives; he was an early advocate for school desegregation. In the 1850s, Douglass observed that New York's facilities and instruction for African American children were vastly inferior to those for European Americans. Douglass called for court action to open all schools to all children. He said that full inclusion within the educational system was a more pressing need for African Americans than political issues such as suffrage.

John Brown

On March 12, 1859, Douglass met with radical abolitionists John Brown, George DeBaptiste, and others at William Webb's house in Detroit to discuss emancipation.[124] Douglass met Brown again when Brown visited his home two months before leading the raid on Harpers Ferry. Brown penned his Provisional Constitution during his two-week stay with Douglass. Also staying with Douglass for over a year was Shields Green, a fugitive slave whom Douglass was helping, as he often did.

Shortly before the raid, Douglass, taking Green with him, travelled from Rochester, via New York City, to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Brown's communications headquarters. He was recognized there by black people, who asked him for a lecture. Douglass agreed, although he said his only topic was slavery. Green joined him on the stage; Brown, incognito, sat in the audience. A white reporter, referring to "Nigger Democracy", called it a "flaming address" by "the notorious Negro Orator".[125]

There, in an abandoned stone quarry for secrecy, Douglass and Green met with Brown and John Henri Kagi, to discuss the raid. After discussions lasting, as Douglass put it, "a day and a night", he disappointed Brown by declining to join him, considering the mission suicidal. To Douglass's surprise, Green went with Brown instead of returning to Rochester with Douglass. Anne Brown said that Green told her that Douglass promised to pay him on his return, but David Blight called this "much more ex post facto bitterness than reality".[126]

Almost all that is known about this incident comes from Douglass. It is clear that it was of immense importance to him, both as a turning point in his life—not accompanying John Brown—and its importance in his public image. The meeting was not revealed by Douglass for 20 years. He first disclosed it in his speech on John Brown at Storer College in 1881, trying unsuccessfully to raise money to support a John Brown professorship at Storer, to be held by a black man. He again referred to it stunningly in his last Autobiography.

After the raid, which took place between October 16 and 18, 1859, Douglass was accused both of supporting Brown and of not supporting him enough.[127] He was nearly arrested on a Virginia warrant,[128][129][130] and fled for a brief time to Canada before proceeding onward to England on a previously planned lecture tour, arriving near the end of November.[131] During his lecture tour of Great Britain, on March 26, 1860, Douglass delivered a speech before the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society in Glasgow, "The Constitution of the United States: is it pro-slavery or anti-slavery?", outlining his views on the American Constitution.[132] That month, on the 13th, Douglass's youngest daughter Annie died in Rochester, New York, at age 10. Douglass sailed back from England the following month, traveling through Canada to avoid detection.

Years later, in 1881, Douglass shared a stage at Storer College in Harpers Ferry with Andrew Hunter, the prosecutor who secured Brown's conviction and execution. Hunter congratulated Douglass.[133]

Photography

Douglass considered photography very important in ending slavery and racism, and believed that the camera would not lie, even in the hands of a racist white person, as photographs were an excellent counter to many racist caricatures, particularly in blackface minstrelsy. He was the most photographed American of the 19th century, consciously using photography to advance his political views.[134][135] He never smiled, specifically so as not to play into the racist caricature of a happy enslaved person. He tended to look directly into the camera and confront the viewer with a stern look.[136][137]

Civil War years

Before the Civil War

By the time of the Civil War, Douglass was one of the most famous black men in the country, known for his orations on the condition of the black race and on other issues such as women's rights. His eloquence gathered crowds at every location. His reception by leaders in England and Ireland added to his stature.

He had been seriously proposed for the congressional seat of his friend and supporter Gerrit Smith, who declined to run again after his term ended in 1854.[138][139] Smith recommended to him that he not run, because there were "strenuous objections" from members of Congress.[140] The possibility "afflicted some with convulsions, others with panic, more with an astonishing flow of exceedingly select and nervous language", "giving vent to all sorts of linguistic enormities."[141] If the House agreed to seat him, which was unlikely, all the Southern members would walk out, so the country would finally be split.[139][142] No black person would serve in Congress until 1870, just after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment.

Fight for emancipation and suffrage

Douglass and the abolitionists argued that because the aim of the Civil War was to end slavery, African Americans should be allowed to engage in the fight for their freedom. Douglass publicized this view in his newspapers and several speeches. After Lincoln had finally allowed black soldiers to serve in the Union army, Douglass helped the recruitment efforts, publishing his famous broadside Men of Color to Arms! on March 21, 1863.[143] His eldest son, Charles Douglass, joined the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, but was ill for much of his service.[75] Lewis Douglass fought at the Battle of Fort Wagner.[144] Another son, Frederick Douglass Jr., also served as a recruiter.

With the North no longer obliged to return slaves to their owners in the South, Douglass fought for equality for his people. Douglass conferred with President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 on the treatment of black soldiers[145] and on plans to move liberated slaves out of the South.

President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863, declared the freedom of all slaves in Confederate-held territory. (Slaves in Union-held areas were not covered because the proclamation was permissible under the Constitution only as a war measure; they were freed with the adoption of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865.) Douglass described the spirit of those awaiting the proclamation: "We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky ... we were watching ... by the dim light of the stars for the dawn of a new day ... we were longing for the answer to the agonizing prayers of centuries."[146]

During the U.S. Presidential Election of 1864, Douglass supported John C. Frémont, who was the candidate of the abolitionist Radical Democracy Party. Douglass was disappointed that President Lincoln did not publicly endorse suffrage for black freedmen. Douglass believed that since African American men were fighting for the Union in the American Civil War, they deserved the right to vote.[147]

After Lincoln's death

The postwar ratification of the 13th Amendment, on December 6, 1865, outlawed slavery, "except as a punishment for crime." The 14th Amendment provided for birthright citizenship and prohibited the states from abridging the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States or denying any "person" due process of law or equal protection of the laws. The 15th Amendment protected all citizens from being discriminated against in voting because of race.[116] After Lincoln had been assassinated, Douglass conferred with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of black suffrage.[148]

On April 14, 1876, Douglass delivered the keynote speech at the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington's Lincoln Park. He spoke frankly about the complex legacy of Lincoln, noting what he perceived as both positive and negative attributes of the late President.[149] Calling Lincoln "the white man's President," Douglass criticized Lincoln's tardiness in joining the cause of emancipation, noting that Lincoln initially opposed the expansion of slavery but did not support its elimination: "He had been ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the humanity of the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people. Lincoln was neither our man or our model".[149] But Douglass also asked, "Can any colored man, or any white man friendly to the freedom of all men, ever forget the night which followed the first day of January 1863, when the world was to see if Abraham Lincoln would prove to be as good as his word?"[150] He also said: "Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery...." Most famously, he added: "Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined."[149]

The crowd, roused by his speech, gave Douglass a standing ovation. Lincoln's widow Mary Lincoln supposedly gave Lincoln's favorite walking-stick to Douglass in appreciation. That walking stick still rests in his final residence, "Cedar Hill" in Washington, D.C., now preserved as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

After delivering the speech, Douglass immediately wrote to the National Republican newspaper in Washington (which published his letter five days later, on April 19), criticizing the statue's design and suggesting the park could be improved by more dignified monuments of free black people. "The negro here, though rising, is still on his knees and nude," Douglass wrote. "What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man."[151]

Reconstruction era

After the Civil War, Douglass continued to work for equality for African Americans and women. Due to his prominence and activism during the war, Douglass received several political appointments. He served as president of the Reconstruction-era Freedman's Savings Bank.[152]

Meanwhile, white insurgents had quickly arisen in the South after the war, organizing first as secret vigilante groups, including the Ku Klux Klan. Armed insurgency took different forms. Powerful paramilitary groups included the White League and the Red Shirts, both active during the 1870s in the Deep South. They operated as "the military arm of the Democratic Party", turning out Republican officeholders and disrupting elections.[153] Starting 10 years after the war, Democrats regained political power in every state of the former Confederacy and began to reassert white supremacy. They enforced this by a combination of violence, late 19th-century laws imposing segregation and a concerted effort to disfranchise African Americans. New labor and criminal laws also limited their freedom.[154]

To combat these efforts, Douglass supported the presidential campaign of Ulysses S. Grant in 1868. In 1870, Douglass started his last newspaper, the New National Era, attempting to hold his country to its commitment to equality.[75] President Grant sent a congressionally sponsored commission, accompanied by Douglass, on a mission to the West Indies to investigate whether the annexation of Santo Domingo would be good for the United States. Grant believed annexation would help relieve the violent situation in the South by allowing African Americans their own state. Douglass and the commission favored annexation, but Congress remained opposed to annexation. Douglass criticized Senator Charles Sumner, who opposed annexation, stating that if Sumner continued to oppose annexation he would "regard him as the worst foe the colored race has on this continent."[155]

After the midterm elections, Grant signed the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act) and the second and third Enforcement Acts. Grant used their provisions vigorously, suspending habeas corpus in South Carolina and sending troops there and into other states. Under his leadership over 5,000 arrests were made. Grant's vigor in disrupting the Klan made him unpopular among many whites but earned praise from Douglass. A Douglass associate wrote that African Americans "will ever cherish a grateful remembrance of [Grant's] name, fame and great services."

In 1872, Douglass became the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States, as Victoria Woodhull's running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket. He was nominated without his knowledge. Douglass neither campaigned for the ticket nor acknowledged that he had been nominated.[7] In that year, he was presidential elector at large for the State of New York, and took that state's votes to Washington, D.C.[156]

However, in early June of that year, Douglass's third Rochester home, on South Avenue, burned down; arson was suspected. There was extensive damage to the house, its furnishings, and the grounds; in addition, sixteen volumes of the North Star and Frederick Douglass' Paper were lost. Douglass then moved to Washington, D.C.[157]

Throughout the Reconstruction era, Douglass continued speaking, emphasizing the importance of work, voting rights and actual exercise of suffrage. His speeches for the twenty-five years following the war emphasized work to counter the racism that was then prevalent in unions.[158] In a November 15, 1867, speech he said:

A man's rights rest in three boxes. The ballot box, jury box, and the cartridge box. Let no man be kept from the ballot box because of his color. Let no woman be kept from the ballot box because of her sex.[159]

Douglass spoke at many colleges around the country, including Bates College in Lewiston, Maine, in 1873.

In 1881, at Storer College in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, Douglass delivered a speech praising John Brown and revealing unknown information about their relationship, including their meeting in an abandoned stone quarry near Chambersburg shortly before the raid.[133]

Frederick Douglass House

In 1877 Frederick Douglass bought a house that included a big yard, as well as a studio where he did most of his work; he lived in this house from 1878 until his death in 1895, and it was named the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

Final years in Washington, D.C.

The Freedman's Savings Bank went bankrupt on June 29, 1874, just a few months after Douglass became its president in late March.[160] During that same economic crisis, his final newspaper, The New National Era, failed in September.[161] When Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was elected president, he named Douglass United States Marshal for the District of Columbia, making him the first person of color to be so named. The United States Senate voted to confirm him on March 17, 1877.[162] Douglass accepted the appointment, which helped assure his family's financial security.[75] During his tenure, Douglass was urged by his supporters to resign from his commission, since he was never asked to introduce visiting foreign dignitaries to the President, which is one of the usual duties of that post. However, Douglass believed that no covert racism was implied by the omission and stated that he was always warmly welcomed in presidential circles.[163][164]

In 1877, Douglass visited his former enslaver Thomas Auld on his deathbed, and the two men reconciled. Douglass had met Auld's daughter, Amanda Auld Sears, some years prior. She had requested the meeting and had subsequently attended and cheered one of Douglass's speeches. Her father complimented her for reaching out to Douglass. The visit also appears to have brought closure to Douglass, although some criticized his effort.[108]

That same year, Douglass bought the house that was to be the family's final home in Washington, D.C., on a hill above the Anacostia River. He and Anna named it Cedar Hill (also spelled CedarHill). They expanded the house from 14 to 21 rooms and included a china closet. One year later, Douglass purchased adjoining lots and expanded the property to 15 acres (61,000 m2). The home is now preserved as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

In 1881, Douglass published the final edition of his autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he updated in 1892. In 1881, he was appointed Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia. His wife Anna Murray Douglass died in 1882, leaving the widower devastated. After a period of mourning, Douglass found new meaning from working with activist Ida B. Wells. He remarried in 1884, as mentioned above.

Douglass also continued his speaking engagements and travel, both in the United States and abroad. With new wife Helen, Douglass toured the UK[165] including Wales (possibly by invitation from abolitionist Jessie Donaldson), Ireland, France, Italy, Egypt, and Greece from 1886 to 1887. He became known for advocating Irish Home Rule and supported Charles Stewart Parnell in Ireland.

At the 1888 Republican National Convention, Douglass became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States in a major party's roll call vote.[166] That year, Douglass spoke at Claflin College, a historically black college in Orangeburg, South Carolina, and the state's oldest such institution.[167]

Many African Americans, called Exodusters,[citation needed] escaped the Klan and racially discriminatory laws in the South by moving to Kansas, where some formed all-black towns to have a greater level of freedom and autonomy. Douglass favored neither this nor the Back-to-Africa movement. He thought the latter resembled the American Colonization Society, which he had opposed in his youth. In 1892, at an Indianapolis conference convened by Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, Douglass spoke out against the separatist movements, urging African Americans to stick it out.[75] He made similar speeches as early as 1879 and was criticized both by fellow leaders and some audiences, who even booed him for this position.[168] Speaking in Baltimore in 1894, Douglass said, "I hope and trust all will come out right in the end, but the immediate future looks dark and troubled. I cannot shut my eyes to the ugly facts before me."[169]

President Harrison appointed Douglass as the United States's minister resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti and Chargé d'affaires for Santo Domingo in 1889,[170] but Douglass resigned the commission in July 1891 when it became apparent that the American President was intent upon gaining permanent access to Haitian territory regardless of that country's desires.[171] In 1892, Haiti made Douglass a co-commissioner of its pavilion at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.[172]

In 1892, Douglass constructed rental housing for blacks, now known as Douglass Place, in the Fells Point area of Baltimore. The complex still exists, and in 2003 was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[173][174]

Death

On February 20, 1895, Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. During that meeting, he was brought to the platform and received a standing ovation. Shortly after he returned home, Douglass died of a heart attack.[175] He was 77.

His funeral was held at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church. Although Douglass had attended several churches in the nation's capital, he had a pew here and had donated two standing candelabras when this church had moved to a new building in 1886. He also gave many lectures there, including his last major speech, "The Lesson of the Hour."[58]

Thousands of people passed by his coffin to show their respect. United States senators and Supreme Court justices were pallbearers. Jeremiah Rankin, President of Howard University, delivered "a masterly address". A letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton was read. The Secretary of the Haitian Legation "expressed the condolence of his country in melodious French."[176]

Douglass's coffin was transported to Rochester, New York, where he had lived for 25 years, longer than anywhere else in his life. His body was received in state at City Hall, flags were flown at half mast, and schools adjourned.[177] He was buried next to Anna in the Douglass family plot of Mount Hope Cemetery.[178] Helen was also buried there, in 1903. His grave is, with that of Susan B. Anthony, the most visited in the cemetery.[178] A marker, erected by the University of Rochester and other friends, describes him as "escaped slave, abolitionist, suffragist, journalist and statesman, founder of the Civil Rights Movement in America".[178]

Works

Writings

- 1845. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself (first autobiography).

- 1853. "The Heroic Slave." pp. 174–239 in Autographs for Freedom, edited by Julia Griffiths. Boston: Jewett and Company. Also in Speeches & Writings volume of The Frederick Douglass Collection: A Library of America Boxed Set (2023). Published by itself in a Dover Thrift Edition (2019).

- 1855. My Bondage and My Freedom (second autobiography).

- 1881 (revised 1892). Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (third and final autobiography).

- 1847–1851. The North Star, an abolitionist newspaper founded and edited by Douglass. He merged the paper with another, creating Frederick Douglass' Paper.

- 1886. Three Addresses on the Relations Subsisting between the White and Colored People of the United States, at Gutenberg.org

- 1950–1955. The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass (5 volumes, edited by Philip S. Foner). New York: International Publishers. Supplementary volume 5 published in 1975.

- 2012. In the Words of Frederick Douglass: Quotations from Liberty's Champion, edited by John R. McKivigan and Heather L. Kaufman. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4790-7.

- 2023. The Frederick Douglass Collection: A Library of America Boxed Set, including Autobiographies, edited by Henry Louis Gates and Speeches & Writings, edited by David W. Blight, Library of America, two volumes, 2,097 pages.

Speeches

- 1841. "The Church and Prejudice"[179]

- 1852. "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?"[180] In 2020, National Public Radio produced a video of descendants of Douglass reading excerpts from the speech.[181]

- 1859. Self-Made Men.[182]

- 1863, July 6. "Speech at National Hall, for the Promotion of Colored Enlistments."[183]

- 1881.[133]

Poetry

- 1847. "Liberty", an eight-line poem, was written by Douglass in his notebook on September 13, 1847, in Cleveland, Ohio. Since mid-August he and William Lloyd Garrison, on a Western tour for the abolitionist movement, had been traveling through Ohio, where their receptions ranged from hospitable to enthusiastic. This raised Douglass's spirits considerably after he had faced an onslaught of "rotten eggs and all manner of stones and brickbats" while speaking a few weeks earlier in the courthouse at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.[184] As a result of his receptions in Ohio, he was moved to write poetry on at least one other occasion in that state after he had written the poem "Liberty". The handwritten poem is now held in the Xavier University of Louisiana, Archives & Special Collections.[185]

Legacy and honors

Biographer David Blight states that Douglass "played a pivotal role in America's Second Founding out of the apocalypse of the Civil War, and he very much wished to see himself as a founder and a defender of the Second American Republic."[186]

Roy Finkenbine argues:[187]

The most influential African American of the nineteenth century, Douglass made a career of agitating the American conscience. He spoke and wrote on behalf of a variety of reform causes: women's rights, temperance, peace, land reform, free public education, and the abolition of capital punishment. But he devoted the bulk of his time, immense talent, and boundless energy to ending slavery and gaining equal rights for African Americans. These were the central concerns of his long reform career. Douglass understood that the struggle for emancipation and equality demanded forceful, persistent, and unyielding agitation. And he recognized that African Americans must play a conspicuous role in that struggle. Less than a month before his death, when a young black man solicited his advice to an African American just starting out in the world, Douglass replied without hesitation: ″Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!″

The Episcopal Church remembers Douglass with a Lesser Feast[188][189] annually on its liturgical calendar for February 20,[190] the anniversary of his death. Many public schools have also been named in his honor. Douglass still has living descendants today, such as Ken Morris, who is also a descendant of Booker T. Washington.[191] Other honors and remembrances include:

- In 1871, a bust of Douglass was unveiled at Sibley Hall, University of Rochester.[192]

- In 1895, the first hospital for black people in Philadelphia, PA, was named the Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital. Black medical professionals, excluded from other facilities, were trained and employed there. In 1948, it merged to form Mercy-Douglass Hospital.[193]

- In 1899, a statue of Frederick Douglass was unveiled in Rochester, New York, making Douglass the first African-American to be so memorialized in the country.[194][195]

- In 1921, members of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity (the first African-American intercollegiate fraternity) designated Frederick Douglass as an honorary member. Douglass thus became the only man to receive an honorary membership posthumously.[196]

- The Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge, sometimes referred to as the South Capitol Street Bridge, just south of the US Capitol in Washington, D.C., was built in 1950 and named in his honor.

- In 1962, his home in Anacostia (Washington, D.C.) became part of the National Park System[197] and in 1988 was designated the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

- In 1965, the United States Postal Service honored Douglass with a stamp in the Prominent Americans series.

- In 1999, Yale University established the Frederick Douglass Book Prize for works in the history of slavery and abolition, in his honor. The annual $25,000 prize is administered by the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History and the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Frederick Douglass to his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[198]

- In 2003, Douglass Place, the rental housing units that Douglass built in Baltimore in 1892 for blacks, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- In 2005, Douglass was inducted into the National Abolition Hall of Fame, in Peterboro, New York.

- In 2007, the former Troup–Howell Bridge, which carried Interstate 490 over the Genesee River in Rochester, was redesigned and renamed the Frederick Douglass – Susan B. Anthony Memorial Bridge.

- In 2010, the Frederick Douglass Memorial was unveiled at Frederick Douglass Circle at the northwest corner of Central Park in New York City.[199][200]

- In 2010, the New York Writers Hall of Fame inducted Douglass in its inaugural class.

- On June 12, 2011, Talbot County, Maryland, installed a seven-foot (2-meter) bronze statue of Douglass on the lawn of the county courthouse in Easton, Maryland.[201]

- On June 19, 2013, a statue of Douglass by Maryland artist Steven Weitzman was unveiled[202] in the United States Capitol Visitor Center as part of the National Statuary Hall Collection, the first statue representing the District of Columbia.[203]

- On September 15, 2014, under the leadership of Governor Martin O'Malley a portrait of Frederick Douglass was unveiled at his official residence in Annapolis, MD. This painting, by artist Simmie Knox, is the first African-American portrait to grace the walls of Government House. Commissioned by Eddie C. Brown, founder of Brown Capital Management, LLC,[204] the painting was presented at a reception by the Governor.

- On January 7, 2015, in honor of Governor Martin O'Malley's last Board of Public Works meeting, a portrait of Frederick Douglass was presented to him by Peter Franchot.[205] Two editions of this artwork, by artist Benjamin Jancewicz, were purchased from Galerie Myrtis by Peter Franchot and his wife Ann both as a gift for the Governor as well as to add to their own collection. The Governor's edition now hangs in his office.[206][non-primary source needed]

- In November 2015, the University of Maryland dedicated Frederick Douglass Plaza, an outdoor space where visitors can read quotes and see a bronze statue of Douglass.[207]

- On October 18, 2016, the Council of the District of Columbia voted that the city's new name as a State is to be "Washington, D.C.", and that "D.C." is to stand for "Douglass Commonwealth."[208]

- On April 3, 2017, the United States Mint began issuing quarters with an image of Frederick Douglass on the reverse, with the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in the background. The coin is part of the America the Beautiful Quarters series.[209]

- On May 20, 2018, Douglass was awarded an honorary law degree from the University of Rochester. The degree, which was accepted by Douglass's great-great-great-grandson, was the first posthumous honorary degree that the university had granted.[210][211]

- Douglass gave his last public lecture on February 1, 1895, at West Chester University, 19 days before his death. Today, there is a statue of him on the university campus commemorating this event. The Frederick Douglass Institute has a West Chester University program for advancing multicultural studies across the curriculum and for deepening the intellectual heritage of Douglass.[212][213]

- In New York State there is the "Let's Have Tea" sculpture of Douglass and Susan B. Anthony.[214]

- On September 30, 2019, Newcastle University opened the 'Frederick Douglass Centre', a key teaching component for their School of Computing and Business School. Frederick Douglass stayed in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1846 on a street adjacent to the new university campus.[215]

- A statue of Douglass located in Rochester, New York's Maplewood Park was vandalized and torn down over the weekend of July 4, 2020.[216][217]

- In 2020, Douglas Park in Chicago, which was named for U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas, was renamed Douglass Park, in honor of Frederick and Anna Douglass. In the 1850s the senator had promoted "popular sovereignty" as a middle position on the slavery issue and made "blatant assertions of white superiority."[218] The name change was the result of a multi-year student-led campaign to rename the park.[219]

- A plaque on Gilmore Place in Edinburgh, Scotland marks his stay there in 1846. In 2020 a mural of his image was added nearby.

- On June 19, 2021, on Boston Street in the Canton neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland, two panels were unveiled at the spot where, as it had shortly before been discovered, Douglass had boarded the train that took him to his freedom from enslavement.[40][41][42]

- On August 18, 2021, the Frederick Douglass Park in Lynn, Massachusetts was dedicated, directly across the street from the site of the Central Square railroad depot where Douglass was forcibly removed from the train in 1841. The park features a bronze bas-relief sculpture of Douglass.[220]

- In 2020, the Greater Rochester International Airport was renamed the Frederick Douglass Greater Rochester International Airport.

- On January 18, 2023, Governor Wes Moore was sworn in as governor of Maryland on a Bible owned by Douglass.[221]

- In October 2023, it was announced that a plaque commemorating one of Douglass' visits to Liverpool would be placed outside the Everyman Theatre on Hope Street.[222] The theater was built on the original site of Hope Hall, a chapel where Douglass spoke on January 19, 1860.

In popular culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Film and television

- Robert Guillaume portrays Douglass during a speech about the American slave trade in the 1985 miniseries North and South (Season 1, episode 3).[223]

- Glory (1989) features Douglass, played by Raymond St. Jacques, as a friend of Francis George Shaw.

- In Ken Burns' 1990 documentary The Civil War, Douglass is voiced by actor Morgan Freeman.

- The 2004 mockumentary film C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America features the figure of Douglass in an alternative history.

- In Akeelah and the Bee (2006), characters discuss Douglass near a bronze bust of him by sculptor Tina Allen.[224]

- The 2008 documentary film Frederick Douglass and the White Negro tells the story of Douglass in Ireland and the relationship between African and Irish Americans during the American Civil War.

- Douglass appears in Freedom, where he is portrayed by Byron Utley.[225]

- In the 2015 documentary film The Gettysburg Address, the role of Frederick Douglass is voiced by actor Laurence Fishburne.

- A miniseries based on James McBride's 2013 novel, The Good Lord Bird, was released in 2020, with Daveed Diggs as Douglass.[226] Douglass is portrayed negatively.

- On February 23, 2022, HBO released a one-hour documentary titled Frederick Douglass: In Five Speeches, based on David W. Blight's Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.[227]

- Douglass was portrayed by Elvis Nolasco in the 2024 Apple TV+ miniseries series Manhunt.[228]

Literature

- The 1946 novel A Star Pointed North by Edmund Fuller presents an account of Douglass's life.[229]

- Terry Bisson's Fire on the Mountain (1988) is an alternate-history novel in which John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry succeeded and, instead of the Civil War, the Black slaves emancipated themselves in a massive slave revolt. In this history, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman are the revered founders of a Black state created in the Deep South.

- Douglass is a major character in the novel How Few Remain (1997) by Harry Turtledove, depicted in an alternate history in which the Confederacy won the Civil War and Douglass must continue his anti-slavery campaign into the 1880s.

- Douglass appears in Flashman and the Angel of the Lord (1994) by George MacDonald Fraser.

- Douglass, his wife, and his alleged mistress, Ottilie Assing, are the main characters in Jewell Parker Rhodes' Douglass' Women (New York: Atria Books, 2002).

- Douglass is the protagonist of Richard Bradbury's novel Riversmeet (Muswell Press, 2007), a fictionalized account of Douglass's 1845 speaking tour of the British Isles.[230]

- Douglass's time in Ireland is fictionalized in Colum McCann's TransAtlantic (2013).[231]

- A comedic representation of Douglass is made in James McBride's 2013 novel The Good Lord Bird.[232]

- In 2019, author David W. Blight was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for History for Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.[233]

Painting

- In 1938–39, African-American artist Jacob Lawrence created The Frederick Douglass series of narrative paintings. They were part of the historical series started by Lawrence in 1937, which included painted panels about prominent Black historical figures such as Toussaint Louverture and Harriet Tubman. During his preparatory work, Lawrence conducted research at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, drawing primarily from the autobiographies of Frederick Douglass: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845) and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881).[234] For this series the artist used a multipanel-plus-caption format that allowed him to develop a serial narrative that was not possible to convey by means of traditional portrait or history painting.[235] Instead of reproducing Douglass's original narratives verbatim, Lawrence constructed his own visual and textual narrative in the form of 32 panels painted in tempera and accompanied with Lawrence's own captions. The structure of the painting series is linear and consists of three parts (the slave, the fugitive, the free man) which offer an epic chronicle of Douglass's transformation from slave to leader in the struggle for the liberation of black people.[236] The Frederick Douglass series is currently in the Hampton University Museum.