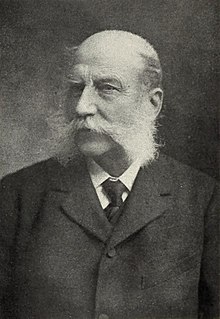

Frederic W. Rhinelander

Frederic W. Rhinelander | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd President of the Metropolitan Museum of Art | |

| In office 1902–1904 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Gurdon Marquand |

| Succeeded by | John Pierpont Morgan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Frederic William Rhinelander February 12, 1828 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | September 24, 1904 (aged 76) Stockbridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Frances Davenport Skinner

(m. 1851; died 1899) |

| Children | 8, including Philip |

| Parent(s) | Frederic William Rhinelander Mary Lucy Ann Stevens Rhinelander |

| Relatives | Frederic R. King (grandson) Edith Wharton (niece) Thomas Newbold (nephew) Ebenezer Stevens (grandfather) John Austin Stevens (uncle) Alexander Stevens (uncle) John Austin Stevens (cousin) Samuel Stevens Sands (cousin) |

| Alma mater | Columbia University |

Frederic William Rhinelander (February 12, 1828 – September 24, 1904) was an American who was prominent in New York society during the Gilded Age and served as president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Early life

[edit]Rhinelander was born in New York City on February 12, 1828. He was the only son of four children born to Frederic William Rhinelander (1796–1836) and Mary Lucretia "Lucy Ann" (née Stevens) Rhinelander (1798–1877).[1] Among his sisters was Lucretia Stevens Rhinelander, who married George Frederic Jones[2] (parents of novelist and decorator Edith (née Jones) Wharton and Frederic Rhinelander Jones);[3] Mary Elizabeth Rhinelander, who married Thomas Haines Newbold[2] (parents of New York State Senator Thomas Newbold[4]); and Eliza Lucille Rhinelander, who married William Edgar.[5]

His paternal grandparents were William Rhinelander and Mary (née Robert) Rhinelander,[6] and his uncles included Philip Rhinelander,[7] a member of the U.S. Congress, William Christopher Rhinelander (grandfather of T.J. Oakley Rhinelander and great-grandfather of Anita de Braganza), and New York City Alderman John Robert Rhinelander.[8] His paternal grandmother was the daughter of Col. Robert, an officer under Gen. George Washington during the American Revolutionary War.[8] His mother was the twelfth and last child of Major General Ebenezer Stevens and his second wife, Lucretia (née Ledyard) Sands Stevens.[8] Among his maternal uncles were banker John Austin Stevens (father of John Austin Stevens, founder of the Sons of the Revolution), and surgeon Alexander Hodgdon Stevens.[9] From his grandmother's first marriage, he was a cousin of the banker Samuel Stevens Sands.[10]

Rhinelander's great-great grandfather, Philip Jacob Rhinelander, was a German-born French Huguenot who immigrated to the United States in 1686 following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes,[11] settling in the newly formed French Huguenot community of New Rochelle, where he amassed considerable property holdings which became the basis for the Rhinelander family's wealth.[12]

Rhinelander graduated from Columbia University in 1847.[13]

Career

[edit]In 1876, Rhinelander began serving as president of the Milwaukee, Lake Shore & Western Railroad. Established in 1856, the railroad was taken over by its Eastern bondholders who added Rhinelander and his cousin, Samuel Stevens Sands, to the Board with Rhinelander as president. By 1879, the Railroad owned 188.1 miles of road.[14] By 1889, Rhinelander's son, F. W. Rhinelander Jr., had been installed as assistant to the president and was based in Milwaukee.[15]

Metropolitan Museum of Art

[edit]Rhinelander was a founding trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1871 along with Theodore Roosevelt Sr., William Cullen Bryant, Andrew Haswell Green, Alexander Turney Stewart, and John A. Dix.[16] He traveled extensively in Europe seeking to secure "new works of art and to study techniques of organization and preservation at museums and galleries."[3] He was responsible for securing the helmet of Jeanne d'Arc, the Pompeian room, the portrait of the Princess de Condé by Nicolas de Largillière[16][17]

After the death of Museum president, Henry Gurdon Marquand, in 1902, Rhinelander, who had been vice-president of the Museum since 1892,[18] became the president. He served in this role until his death in 1904.[16] After his death, the banker and philanthropist J. Pierpont Morgan became president of the Met and served until his death in 1913.

Personal life

[edit]On November 5, 1851, Rhinelander was married to Frances Davenport Skinner (13 Sep 1828–8 Dec 1899).[19] Frances was a daughter of the Rev. Thomas Harvey Skinner and Frances Louisa (née Davenport) Skinner. The Rhinelanders had a home in New York City and had a French Second Empire style home at 10 Redwood Street in Newport, Rhode Island, built by John Hubbard Sturgis build between 1863 and 1864 (today it is an annex to the Redwood Library located across the street).[20] Together, they were the parents of eight children, including:[21]

- Mary Frederica Rhinelander (1852–1932), who married William Cabell Rives III (1850–1938),[22] a grandson of William Cabell Rives.[5][23]

- Frances Davenport Rhinelander (b. 1855), who married Rev. William Morgan-Jones of Cardiff, Wales in 1900.[24]

- Ethel Ledyard Rhinelander (1857–1925),[25] who married LeRoy King (1857–1895)[26] in 1881.[27]

- Frederic William Rhinelander (1859–1942),[28] who married Constance Satterlee, daughter of Bishop Henry Y. Satterlee.[29]

- Alice King Rhinelander (1861–1942), who did not marry and lived in Bronxville, New York.[30]

- Helen Lucretia Rhinelander (1864–1898), who married Archdeacon Lewis Cameron (1864–1909)[31] in 1892.[5][32]

- Thomas Newbold Rhinelander (1865–1928), who married Katherine Blake, daughter of Samuel Hume Blake, in 1894.[5]

- Philip Mercer Rhinelander (1869–1939), the Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania who married Helen Maria Hamilton (1870–1956) in, a granddaughter of John Church Hamilton,[33] in 1905.[34][35]

He was a pall-bearer at the funeral of U.S. Representative John Winthrop Chanler in 1877.[36] He was a member of the Mendelssohn Glee Club, the Knickerbocker Club, the Downtown Club, and the South Side Sportsmen's Club.[13][37]

His wife died in Washington on December 8, 1899.[19] Rhinelander died at the Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge, Massachusetts on September 24, 1904.[13] His niece Edith Wharton reportedly "mourned his death, wearing black clothes and canceling social engagements."[3] After a funeral at the Belmont Chapel, he was buried at Island Cemetery in Newport, Rhode Island.[38] The pallbearers at his funeral were J. Pierpont Morgan, F. Augustus Schermerhon, Charles F. McKim, Rutherfurd Stuyvesant, John De Witt Warner, James Goodwin, George Gordon King Jr., and Gen. Luigi Palma di Cesnola.[38] At his death, his estate was valued at $10,000,000.[39]

Descendants

[edit]Through his daughter Ethel, he was the grandfather of Frederic Rhinelander King, a prominent architect with the firm of Wyeth and King.[40]

Legacy

[edit]In 1881, the town of Pelican Rapids in Oneida County, Wisconsin was renamed to Rhinelander, Wisconsin after Rhinelander,[41] in an attempt to induce the railroad to extend a spur to the location to further their lumbering business.[42] The Railroad reached the town in 1882.[41]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Newbold parcel called Fern Tor". academic2.marist.edu. Marist College. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "NYC Marriage & Death Notices 1843–1856 | New York Society Library". www.nysoclib.org. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Roffman, Karin (2010). From the Modernist Annex: American Women Writers in Museums and Libraries. University of Alabama Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780817316983. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "EX-SENATOR NEWBOLD DIES.; Was in 81st Year—Former Head of State's Health Department" (PDF). The New York Times. November 22, 1929. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Stevens, Eugene Rolaz; Bacon, William Plumb (1914). Erasmus Stevens and his descendants. Tobias A. Wright. p. 45. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Young, Ed., Florence E. (1905). Genealogical Record. The Saint Nicholas Society of the City of New York. p. 128. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "Rhinelander Estate". historylakespec.wordpress.com. History of lake pleasant & Speculator. August 31, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Burke, Arthur Meredyth (1991). The Prominent Families of the United States of America. Genealogical Publishing Com. p. 212. ISBN 9780806313085. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.)

- ^ "Samuel Stevens Sands" (PDF). The New York Times. July 26, 1892. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "THE RHINELANDER FAMILY | AN OLD COLONIAL FORTUNE SCRAPS FROM THE FAMILY HISTORY—HOW THE ESTATE WAS ACQUIRED—REMINISCENCES OF THE OLD SUGAR-HOUSE IN WILLIAM-STREET" (PDF). The New York Times. June 23, 1878. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ National American Society (1920). Americana, American historical magazine, Volume 14. University of California. p. 287.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "F. W. RHINELANDER DEAD; He Was President of the Metropolitan Museum of Art" (PDF). The New York Times. September 26, 1904. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ Flower, Frank Abial (1881). History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin: From Pre-historic Times to the Present Date, Embracing a Summary Sketch of the Native Tribes, and an Exhaustive Record of Men and Events for the Past Century; Describing, the City, Its Commercial, Religious, Educational and Benevolent Institutions, Its Government, Courts, Press, and Public Affairs; and Including Nearly Four Thousand Biographical Sketches of Pioneers and Citizens. Chicago: Western Historical Company. pp. 1398–1402. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Annual Report of the Milwaukee, Lake Shore and Western Railway Company | For the Year 1889. Milwaukee, Wis: Swain & Tate, Printers. 1890. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "THE CAREER OF F. W. RHINELANDER – WHO DIED IN STOCKBRDIGE SUNDAY – Used to Spend Much Time in Europe". The Berkshire Eagle. September 27, 1904. p. 8. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "F. W. RHINELANDER, SR., DEAD. – PRESIDENT OF THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART – And One of Its Trustees From the First Organization—Secured for It Some of Its Most Precious Possessions—Died of Heart Disease at Stockbridge". The Sun. September 26, 1904. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Annual Report of the Trustees. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1901. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mrs. Rhinelander to be Buried To-day" (PDF). The New York Times. December 12, 1899. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ Yarnall, James L. (2005). Newport Through Its Architecture: A History of Styles from Postmedieval to Postmodern. University Press of New England. p. 70. ISBN 9781584654919. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "Guide to the Frederick W. Rhinelander family papers 1842–1911" (PDF). library.brown.edu. Newport Historical Society. 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "DR. WILLIAM C. RIVES". The Boston Globe. December 19, 1938. p. 13. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "William C. Rives papers". loc.gov. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "Morgan-Jones – Rhinelander". The New York Times. April 26, 1900. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "MRS. ETHEL KING'S FUNERAL; Bishop Manning Conducts Services in Chapel of Cathedral" (PDF). The New York Times. May 16, 1925. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ "THE FUNERAL OF LEROY KING; Attended by a Distinguished Gathering at Newport, R.I." (PDF). The New York Times. December 10, 1895. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "MRS. LEROY KING STRICKEN.; Daughter of the Late F.W. Rhinelander a Victim of Apoplexy" (PDF). The New York Times. October 30, 1906. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ "F. W. RHINELANDER, 82, IS DEAD IN NEWPORT; Son of Ex-Heud of Museum Here, Once in Railroad Business" (PDF). The New York Times. January 10, 1942. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ "MISS SATTERLEE A BRIDE; Daughter of Late Bishop of Washington Wedded to F. W. Rhinelander" (PDF). The New York Times. April 29, 1910. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ "Alice King Rhinelander" (PDF). The New York Times. August 25, 1942. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "REV. LEWIS CAMERON DEAD.; Archdeacon of Newark Episcopal Dio. cese Dies from Septio Pneumonia" (PDF). The New York Times. October 31, 1909. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "MISS CAMERON WED TO REGINALD LANIER; Bishop Rhinelander, Bride's Cousin, Performs Ceremony in Cathedral of St. John. RECEPTION AT KING HOME Bride Is the Daughter of the Late Archdeacon Lewis Cameron of New Jersey". The New York Times. December 13, 1921. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Reynolds, Cuyler (1914). Genealogical and Family History of Southern New York and the Hudson River Valley: A Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of a Commonwealth and the Building of a Nation. Lewis Historical Publishing Company. p. 1390. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "MARRIED" (PDF). The New York Times. May 10, 1905. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Harvard College (1780-) Class of 1891 (1911). Harvard College Class of 1891 Secretary's Report. Rockwell & Churchill Press. p. 196. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "FUNERAL OF JOHN WINTHROP CHANLER". The New York Times. October 25, 1877. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Club Men of New York: Their Clubs, College Alumni Associations, Occupations, and Business and Home Addresses, with Historical Sketches of Many Prominent New York Organizations. Republic Press. 1902. p. 619. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "BURIAL OF F. W. RHINELANDER.; Services at Belmont Memorial Chapel in Newport" (PDF). The New York Times. September 29, 1904. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ "TEN-MILLION WILL". Star-Gazette. October 1, 1904. p. 2. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "FREDERIC KING, 84, ARCHITECT IS DEAD | Designed Episcopal Church Here" (PDF). The New York Times. March 22, 1972. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hellmann, Paul T. (2006). Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Routledge. p. 1230. ISBN 9781135948597. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Chicago and North Western Railway Company (1908). A History of the Origin of the Place Names Connected with the Chicago & North Western and Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha Railways. p. 117.