Four Year Plan (Cuba)

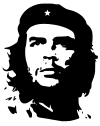

The Four Year Plan was a plan developed by Che Guevara and embraced by various Cuban officials in the economic planning commission JUCEPLAN. The plan was intended to be a classic soviet five year plan, but was reduced to four years, so it would conclude at the same date as other Eastern Bloc five year plans. The plan was to be carried out from 1962 to 1965, but was abandoned prematurely in 1964.[1][2][3]

The plan supposed that Cuba could quickly deemphasize the importance of sugar cultivation in its economy, and instead become a diverse industrial economy. According to Guevara, through the nationalization of industries, and a strong moral enthusiasm for labor taught to the working class, Cuba could rapidly industrialize.[3][4][5] The implementation of the plan resulted in economic crisis. Sugar was Cuba's most lucrative export, and by 1962, sugar exports were in steep decline. The use of moral rewards to compensate hard work also did not lead to increased productivity, but instead to increased worker absenteeism.[3][4] By the end of 1962, the economic crisis would spark a heated debate in Cuba regarding the future of economic planning.[6]

Background

[edit]Sugar in Cuba

[edit]

Cuba is an island with little mineral resources, making foreign trade the most convenient method of obtaining raw materials. Cuba's climate and soil are also highly arable, and thus excellent for agriculture. For these reasons, Cuba has frequently focused on agricultural exports to promote foreign trade.[7]

Cuba's independence from Spain after the Spanish–American War in 1898 and its formation of a republic in 1902 led to investments in the Cuban economy from the United States. The doubling of sugar consumption in the United States between 1903 and 1925 further stimulated investment in Cuba to develop the infrastructure necessary for sugar production. Most of the subsequent development took place in the rural, eastern region of Cuba where sugar production grew the most.[8] From 1895 to 1925, world sugar output increased from seven million tons to 25 million tons. Meanwhile, production in Cuba grew from almost one million tons to over five million tons in 1925. [8]

In 1953, the sugar industry comprised 13% of Cuba's gross domestic product. Every industry in Cuba was tangentially tied to the well-being of the sugar industry. Cuba's focus on sugar resulted in Cuba providing 30% of all world sugar exports between 1950 and 1960.[7]

Cuban Revolution

[edit]Fidel Castro formed the 26th of July Movement with the objective of launching an insurgency in Cuba to overthrow Fulgencio Batista. In the organization's first public manifesto labeled Manifesto No. 1 To The People Of Cuba, published in August 8, 1955, the manifesto urged for industrialization, demanding:

Immediate industrialization of the country by means of a vast plan made and promoted by the state, which will have to decisively mobilize all the human and economic resources of the nation in the supreme effort to free the country from the moral and material prostration in which it finds itself. It is inconceivable that they should be hunger in a country as endowed by nature; every shelf should be stocked with goods and all hands employed productively.[9]

A year later in 1957, the organization issued its Sierra Maestra Manifesto.[10] The manifesto includes demands for industrialization, stating that one of the organization's goals was:

Acceleration of the process of industrialization and the creation of new jobs.[11]

Nationalization and sanctions

[edit]After the Cuban Revolution, rebel leader Che Guevara began advocating for agrarian reform. Within a month after the success of the revolution, on 27 January 1959, Guevara made one of his most significant speeches where he talked about "the social ideas of the rebel army". During this speech he declared that the main concern of the new Cuban government was land distribution.[12] Guevara also made comments on crop diversification, stating:

When we plan out the agrarian reform and observe the new revolutionary laws to complement it and make it viable and immediate, we are aiming at social justice. This means the redistribution of land and also the creation of a vast internal market and crop diversification, two cardinal objectives of the revolutionary government that are inseparable and that cannot be postponed since they involve the people's interest.[13]

Guevara also commented on industrialization, stating:

All economic activities are connected. We must increase the country's industrialization, without overlooking the many problems accompanying such a process. But a policy of encouraging industry demands certain tariff measures to protect nascent industry, as well as an internal market capable of absorbing the new commodities. We cannot increase this market except by giving the great peasant masses broader access to it.[13]

A few months later, 17 May 1959, the agrarian reform law, crafted by Guevara, went into effect, limiting the size of all farms to 1,000 acres (400 ha). Any holdings over these limits were expropriated by the government and either redistributed to peasants in 67-acre (270,000 m2) parcels or held as state-run communes.[14] The law also stipulated that foreigners could not own Cuban sugar-plantations.[15]

A few months after, rebel leader Fidel Castro began an 11-day visit to the United States, starting on April 15, 1959, at the invitation of the American Society of Newspaper Editors.[16] Fidel Castro made the visit in hopes of securing U.S. aid for Cuba. While there he openly spoke of plans to nationalize Cuban lands and at the United Nations he declared Cuba was neutral in the Cold War.[17] A month later, 17 May 1959, the agrarian reform law, crafted by Guevara, went into effect, limiting the size of all farms to 1,000 acres (400 ha). Any holdings over these limits were expropriated by the government and either redistributed to peasants in 67-acre (270,000 m2) parcels or held as state-run communes.[14] The law also stipulated that foreigners could not own Cuban sugar-plantations.[15]

In July the United States suspended the purchase of 700,000 tons of sugar from Cuba, four days later the Soviet Union announced they would buy one million tons of Cuban sugar. In August the United States announced a total economic embargo on Cuba and threatened other Latin American and European nations with reprisals if they did not do the same.[18]

Rise of Che Guevara and formal embargo

[edit]Army officer Huber Matos became disillusioned with the mass expropriations in Cuba, and resigned from his post on October 20, 1959. Matos was swiftly arrested, and created a public scandal.[19] After the scandal, various other disillusioned economists would send in their resignations. Felipe Pazos would resign as head of the National Bank, and Cabinet members Manuel Ray and Faustino Perez also resigned.[20][21]

Guevara acquired the position of Minister of Finance, as well as President of the National Bank.[22] In 1960, Guevara began promoting an idea of rapidly industrializing Cuba, and diversifying Cuba's agriculture.[23]

On 13 October 1960, the US government prohibited the majority of exports to Cuba – the exceptions being medicines and certain foodstuffs – marking the start of an economic embargo. In retaliation, the Cuban National Institute for Agrarian Reform took control of 383 private-run businesses on 14 October, and on 25 October a further 166 US companies operating in Cuba had their premises seized and nationalized, including Coca-Cola and Sears Roebuck.[24] On 16 December, the US then ended its import quota of Cuban sugar.[25]

History

[edit]Implementation

[edit]In 1961, Guevara proposed a four year plan for rapid industrialization that would create a 15% annual growth rate, and a tenfold increase in the production of fruits.[23] On February 23, 1961, the Council of Ministers created the new Ministry of Industries for Che Guevara to head, and execute his new industrialization plan.[26][27] This appointment, combined with other economist positions, placed Guevara at the zenith of his power, as the "virtual czar" of the Cuban economy.[28]

As head of the Ministry of Industries, Guevara announced on the radio program People's University on March 3, 1961 that "accelerated industrialization" would require the centralization of all economic decision making.[4]

In 1961, various Marxist economists from throughout the world were invited to Cuba to assist in economic planning. The central planning board of Cuba: JUCEPLAN, was tasked with creating a four year economic plan. Regino Boti, the head of JUCEPLAN, announced in August 1961, that the country would soon have a 10% rate of economic growth, and the highest living standard in Latin America in 10 years.[29] The plan drafted by JUCEPLAN in 1961, was a four year plan devised to be implemented in 1962 through 1965. It stressed agricultural diversification and rapid industrialization via Soviet assistance.[30]

Guevara also introduced the policy of "socialist emulation" in 1961. The policy awarded exemplary workers with honorary monikers and trophies, but did not reward extra work with extra pay.[31]

Economic decline

[edit]In September 1961, Castro publicly complained that industrialization had stalled because of lazy uncooperative workers.[31]

Historian Jorge I. Domínguez claims that throughout 1960 to 1962, there was no discussion within the Cuban government about altering the economic plan for accelerated industrialization. It wasn't until after the sharp decline in sugar production during the 1962 harvest, that ministers began recognizing the plan's failure, and began considering reform.[3] The sugar harvest of 1962 was 4.8 million tons, a drop from 6.8 million tons in 1961.[32]

In March 1962, Guevara admitted in a speech that the economic plan was a failure, specifically stating it was "an absurd plan, disconnected from reality, with absurd goals and imaginary resources."[23]

Scholar Richard Legé Harris has contested that the demise of the economic plan was the result of a lack of machinery which was typically imported from the United States, but was prevented from being imported due to the embargo, as well as a lack of educated technicians.[33] Luis Fernando Ayerbe has claimed that the crisis was caused by a combination of falling sugar profits and expanding social services. As profits fell, and social services increased, Cuba needed greater consumer goods to give to the poor, but could not provide them due to reduced profits.[32] Samuel Farber has added that the crisis was caused by the earlier flight of educated professionals, a general lack of raw materials causing slow downs in factories, political loyalists being promoted as factory managers, and a highly centralized economy with planners who were disconnected and ignorant of the general Cuban economy.[23]

The failure of the industrialization plan had immediate impacts by 1962. In that year, Cuba introduced a rationing system for food,[34] and froze prices. A new currency was also introduced, which tangentially made all financial savings in the old currency worthless overnight.[35] On August 29, 1962, the Labor Ministry of Cuba drafted Resolution 5798 which gave wage cuts to highly absent and tardy workers.[31]

Debate and further decline

[edit]After the stark economic decline of 1962, Fidel Castro invited Marxist economists around the world to debate two main propositions. One proposition proposed by Che Guevara was that Cuba could bypass any capitalist then "socialist" transition period and immediately become an industrialized "communist" society if "subjective conditions" like public consciousness and vanguard action are perfected. The other proposition held by the Popular Socialist Party was that Cuba required a transitionary period as a mixed economy in which Cuba's sugar economy was maximized for profit before a "communist" society could be established.[36][37][38]

Economic decline continued during this debate, and by 1963, sugar production was down by over a third of its 1961 level.[35] The sugar harvest of that year only brought in 3.8 million tons, the lowest harvest in Cuba in over twenty years.[39] General food production was also down per capita by 40% for the next three years.[40]

In 1963, Castro began to emphasize sugar production in economic planning.[35] In the same year, Guevara resigned from his position as head of Ministry of Industries.[41] Guevara publicly lamented about how the plan required the purchasing of foreign raw materials to create consumer goods, when the price of the raw goods cost just as much as the finished products, and how it was a mistake to neglect the sugar industry.[42]

In 1964, Fidel Castro visited the Soviet Union and agreed to an deal promising Soviet machinery for 24 million tons of sugarcane over the next five years. Cuba's economy was once again refocused on sugar production.[34]

Aftermath

[edit]Sugar production

[edit]As Cuban economic planning began to return to sugar production in 1963, all males ages 18 to 40 were conscripted into the military by 1963, and used as forced labor. Cuba's foreign relations also became deeply tied to sugar. Castro visited the Soviet Union to secure a sugar deal, while Che Guevara traveled to China to secure a sugar deal. After Castro's return from the Soviet Union, the Ministry of Sugar was established in Cuba, and developed a plan to produce 47 million tons of sugar between 1965 and 1970.[43]

At the conclusion of the Great Debate in 1966, Castro endorsed the Guevarist model of production which stressed moral incentives rather than material incentives for labor. In 1968, Cuba engaged in a "Revolutionary Offensive" to consolidate the country's resources to produce 10 million tons of sugar in the 1970 harvest.[44]

Career of Che Guevara

[edit]After the failure of the industrialization plan, Guevara published an article in 1964, titled The Cuban Economy: Its Past, and Its Present Importance, which analyzed Cuba's economic decline. In the article Guevara states that he committed "two principle errors": the diversification of agriculture, and dispersing resources evenly for various agricultural sectors. Specifically on the move away from sugar, Guevara states:

The entire economic history of Cuba had demonstrated that no other agricultural activity would give such returns as those yielded by the cultivation of the sugarcane. At the outset of the Revolution many of us were not aware of this basic economic fact, because a fetishistic idea connected sugar with our dependence on imperialism and with the misery in the rural areas, without analysing the real causes: the relation to the uneven trade balance.[45]

Guevara continued to be critical of the Soviet economic model. In a February 1965 speech, Guevara criticized the Soviet Union for engaging in "exploitative" relationships with third world countries. In his essay published that year, Socialism and the New Man in Cuba, Guevara continued to advocate for an economy based on a moral enthusiasm for self-sacrifice.[46]

While Guevara was making diplomatic visits around the world, East European advisors were invited to Cuba to evaluate the economy, and wrote a report highly critical of Guevara. When Guevara returned to Cuba from world travel in March 1964, he was greeted at the Rancho Boyeros airport by Fidel Castro, Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado, and his wife. Guevara and Castro did not embrace, as was their custom. Later in April, Guevara would depart from Cuba to fight in the Congo.[47]

After Guevara had left Cuba to fight in the Congo, the CIA released a memo titled "The Fall of Che Guevara and the Changing Face of the Cuban Revolution". In the memo, analyst Brian Latell argues that Guevara's exit from Cuba was the result of a schism with Castro. This schism was caused by Guevara aligning with China during the Sino-Soviet split, and Guevara being responsible for Cuba's failed industrialization plan.[48]

References

[edit]- ^ Jefferies, Ian (1993). Socialist Economies and the Transition to the Market A Guide. Taylor and Francis. p. 208. ISBN 9781134903603.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (2013). Cuba A History. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9780718192921.

- ^ a b c d Dominguez, Jorge (2009). Cuba Order and Revolution. Harvard University Press. p. 383-384. ISBN 9780674034280.

- ^ a b c James, Daniel (2001). Che Guevara A Biography. Cooper Square Press. p. 124-125. ISBN 9781461732068.

- ^ Salazar-Carrillo, Jorge; Nodarse-Leon, Andro (2015). Cuba From Economic Take-Off to Collapse Under Castro. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412856362.

- ^ Niess, Frank (2005). Che Guevara. Hauss. p. 89. ISBN 9781904341994.

- ^ a b Brunner, Heinrich (1977). Cuban Sugar Policy from 1963 to 1970 Translated by Marguerite Borchardt and H. F. Broch de Rothermann. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 1-8. ISBN 9780822976158.

- ^ a b Pollitt, Brian (May 2004). "The Rise and Fall of the Cuban Sugar Economy". Journal of Latin American Studies. 36 (2): 319–348. doi:10.1017/S0022216X04007448. JSTOR 3875618.

- ^ Plazas, Luis (1997). "REVOLUTIONARY MANIFESTOS AND FIDEL CASTRO'S ROAD TO POWER" (PDF). ucf.digital.flvc.org. University of Central Florida.

- ^ Immel, Myra (2013). The Cuban Revolution. Greenhaven Press. pp. 100–105. ISBN 9780737763669.

- ^ "Sierra Maestra Manifesto". latinamericanstudies.org. July 12, 1957.

- ^ Kellner 1989, p. 54.

- ^ a b Guevara, Che (January 1959). "Guevara On Social Aims Of The Rebel Army: `Agrarian Reform Was Spearhead Of Combatants' In The Cuban Revolution". themilitant.com. The Militant.

- ^ a b Kellner 1989, p. 57.

- ^ a b Kellner 1989, p. 58.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (15 April 2013). "Fidel Castro visits the U.S., April 15, 1959". Politico. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Stanley, John. "What impact did the Cuban Revolution have on the Cold War?" (PDF).

- ^ Nieto, Clara (2011). Masters of War Latin America and U.S. Aggression From the Cuban Revolution Through the Clinton Years. Seven Stories Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1609800499.

- ^ Anderson, John Lee (2010). Che Guevara A Revolutionary Life (Revised ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 427. ISBN 978-0802197252.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas (2004). Fidel Castro A Biography. Greenwood Press. pp. 49–51. ISBN 0313323011.

- ^ Gonzalez, Servando (2002). The Nuclear Deception Nikita Khrushchev and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Spooks Books. p. 52. ISBN 9780971139152.

- ^ "Ernesto "Che" Guevara".

- ^ a b c d Farber, Samuel (2016). The Politics of Che Guevara Theory and Practice. Haymarket Books. p. 20-25. ISBN 9781608466597.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 214.

- ^ Bourne 1986, p. 215.

- ^ Alvarez de Toledo, Lucia (2013). The Story of Che Guevara. Hachette Book Group. ISBN 9781623652173.

- ^ Franklin, Jane (2016). Cuba and the U.S. Empire A Chronological History. Monthly Review Press. p. 37. ISBN 9781583676066.

- ^ Kellner 1989, p. 55.

- ^ Gott, Richard (2005). Cuba A New History. Yale University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-300-11114-9.

- ^ Todd, Allan; Waller, Sally (2015). History for the IB Diploma Paper 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 227-228. ISBN 9781107558892.

- ^ a b c Bunck, Julie (2010). Fidel Castro and the Quest for a Revolutionary Culture in Cuba. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 131-135. ISBN 9780271040271.

- ^ a b Fernando Ayerbe, Luis (2018). The Cuban Revolution. Editora Unesp. ISBN 9788595462656.

- ^ Lege Harris, Richard (2000). Death of a Revolutionary Che Guevara's Last Mission. Norton. p. 69. ISBN 9780393320329.

- ^ a b McAuslan, Fiona; Norman, Matthew (2003). Cuba. Rough Guides. p. 520. ISBN 9781858289038.

- ^ a b c Cuba A Short History. Cambridge University Press. 1993. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-521-43682-3.

- ^ Kapcia, Antoni (2022). Historical Dictionary of Cuba. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. pp. 261–262. ISBN 9781442264557.

- ^ Cuba's Forgotten Decade How the 1970s Shaped the Revolution. Lexington Books. 2018. p. 10. ISBN 9781498568746.

- ^ Underlid, Even (2021). Cuba Was Different Views of the Cuban Communist Party on the Collapse of Soviet and Eastern European Socialism. Brill. p. 229. ISBN 9789004442900.

- ^ Perez, Louis (2015). Cuba Between Reform and Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 269. ISBN 9780199301447.

- ^ Martinez-Fernandez, Luis (2014). Revolutionary Cuba A History. University Press of Florida. p. 83. ISBN 9780813048765.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Politics The Left and the Right · Volume 1. SAGE Publications. 2005. p. 204. ISBN 9781452265315.

- ^ Llorente, Renzo (2018). The Political Theory of Che Guevara. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 97. ISBN 9781783487189.

- ^ Martinez-Fernandez, Luis (2014). Revolutionary Cuba A History. University Press of Florida. p. 80-100. ISBN 9780813048765.

- ^ Cuba A Different America. Rowman & Littlefield. 1992. p. 42. ISBN 9780847676941.

- ^ Guevara, Ernesto Che (1964). "The Cuban Economy: Its Past, and Its Present Importance". International Affairs. 40 (4). Oxford University Press: 589–599. doi:10.2307/2611726. JSTOR 2611726.

- ^ Goldstone, Jack (2015). The Encyclopedia of Political Revolutions. Taylor & Francis. p. 211. ISBN 9781135937584.

- ^ Quirk, Robert (1993). Fidel Castro. Norton. p. 522-524. ISBN 9780393313277.

- ^ Luther, Eric; Henken, Ted (2001). The Life and Work of Che Guevara. Alpha. p. 205. ISBN 9780028641997.

Sources

[edit]- Bourne, Peter G. (1986). Fidel: A Biography of Fidel Castro. New York City: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 978-0-396-08518-8.

- Kellner, Douglas (1989). Ernesto "Che" Guevara (World Leaders Past & Present). Chelsea House Publishers. p. 112. ISBN 1555468357.