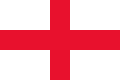

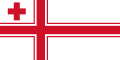

Flag of England

| |

| Use | National flag |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 3:5[1] |

| Design | A white field with centred red cross. Argent, a cross gules |

The flag of England is the national flag of England, a constituent country of the United Kingdom. It is derived from Saint George's Cross (heraldic blazon: Argent, a cross gules). The association of the red cross as an emblem of England can be traced back to the Late Middle Ages when it was gradually, increasingly, used alongside the Royal Banner. It became the only saint's flag permitted to be flown in public as part of the English Reformation and at a similar time became the pre-eminent maritime flag referred to as a white ensign. It was used as a component in the design of the Union Jack in 1606.[2]

It has been widely used since the 1990s, specifically at national sporting events, especially during the campaigns of England's national football teams.[3]

Origins

In 1188 Henry II of England and Philip II of France agreed to go on a crusade, and that Henry would use a white cross and Philip a red cross (and not vice versa as suggested by later use).[citation needed]

There then follows a historiographical tradition claiming that Richard the Lionheart himself adopted the full red cross flag and the patron saint from the Republic of Genoa at some point during his crusade. This idea can be traced to the Victorian era,[5] Perrin (1922) refers to it as a "common belief", and it is still popularly repeated today even though it cannot be substantiated.[6] Prince Edward, Duke of Kent made a variation to this in a bilingual preface to a brochure made for the British Pavilion at Genoa Expo '92. The relevant passage read:

The St. George's flag, a red cross on a white field, was adopted by England and the City of London in 1190 for their ships entering the Mediterranean to benefit from the protection of the Genoese fleet. The English Monarch paid an annual tribute to the Doge of Genoa for this privilege[7][8][9]

Red crosses seem to have been used as a distinguishing mark worn by English soldiers from the reign of Edward I (1270s),[10] or perhaps slightly earlier, in the Battle of Evesham of 1265, using a red cross on their uniforms to distinguish themselves from the white crosses used by the rebel barons at the Battle of Lewes a year earlier.[11] Perrin notes a roll of accounts from 1277 where the purchase of cloth for the king's tailor is identified as destined for the manufacture of a large number of pennoncels (pennons attached to lances) and bracers (worn by archers on their left forearms) "of the arms of Saint George" for the use by the king's foot soldiers (pro peditibus regis).[12] Perrin concludes from this that the introduction of the Cross of St George as a "national emblem" is originally due to Edward I. By 1300, there was also a greater "banner of Saint George", but not yet in a prominent function; the king used it among especially banners of king-saints Saint Edward the Confessor and Saint Edmund the Martyr alongside the royal banner.[13] George had become popular as a "warrior saint" during the Crusades, but the saint most closely associated with England was Edward the Confessor. This was so until the time of Edward III, who in thanks for Saint George's supposed intervention in his favour at the Battle of Crécy gave him a special position as a patron saint of the inceptive Order of the Garter in 1348.[14] From that time, his banner was used with increasing prominence alongside the Royal Banner and became a fixed element in the hoist of the Royal Standard. Yet the flag shown for England in the Book of All Kingdoms of 1367 is solid red (while Saint George's Cross is shown for Nice and, in a five-cross version, for Tbilisi). The Wilton Diptych from the late 1390s shows a swallow-tailed Saint George cross pennant held by an angel in between (the then reigning) King Richard II (accompanied by Edward the Confessor and Edmund the Martyr) and a scene of the Virgin and Child flanked by angels wearing Richard's own heraldic devices.[citation needed]

Saint George's Day was considered a "double major feast" from 1415,[15] but George was still eclipsed by his "rivals" Saints Edward and Edmund.[citation needed]

John Cabot, commissioned by Henry VII to sail "under our banners, flags and ensigns", may have taken a Saint George's banner to Newfoundland in 1497.[citation needed]

That Saint George is the primary patron saint of England is among several lasting changes of height of the English Protestant Reformation, via the content which the teenage king and his Protestant advisors issued to all churches and clerics. These rules were the revised prayer book of 1552. Just as with the Marian persecutions (four years of counter-revolution after his natural death) all defecting clerics faced likely deprivation which was the loss of their office and if more broadly heretical, burning at the stake. The book made clear all religious flags, including saints' banners except for Saint George were abolished.[16]

Further use of this cross as a maritime flag alongside royal banners, is found in 1545.[8]

Henry V, the history play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written near 1599 includes the fictitious scene of the battle of Agincourt where the king's final rally is:

Cry 'God for Harry! England, and Saint George!"

[Exeunt. Alarum, and chambers go off.][17]

thus promoting the notion that the cult or festivities specifically to the saint, or focus on the Order of the Garter put him significantly ahead of two other national saints – instead of depicting that they were approximately equal. The quote became rapidly well known in London, across social classes, and thus imagery entrenched that Saint George was "historically" the primary saint.[citation needed]

In 1606, after the Union of the Crowns in 1603, it was combined with the Scottish St Andrew's Cross to form the Union Jack, which James VI & I ordered be flown from the main tops of ships from both England and Scotland. The "Red Crosse" continued to be flown from the fore-top by James' subjects in "South Britaine"—i.e., the Saint George cross was used with the new union flag on English vessels.[citation needed]

In the 19th century, it became desirable for all nations of Europe (and later worldwide) to identify a national flag.[citation needed] During that time, the terms Britain and England were used largely interchangeably, the Union Flag was used as national flag de facto, even though never officially adopted. The observation that the Cross of St George is the "national flag of England" (as opposed to the Union Flag being the flag of all of the United Kingdom) was made in the context of Irish irredentism, as noted by G. K. Chesterton in 1933:

As a very sensible Irishman said in a letter to a Dublin paper: "The Union Jack is not the national flag of England." The national flag of England is the Cross of St. George; and that, oddly enough, was splashed from one end of Dublin to the other; it was mostly displayed on shield-shaped banners, and may have been regarded by many as merely religious.[18]

Derived flags

Union Flag

The flag of England is one of the key components of the Union Flag. The Union Flag has been used in a variety of forms since the proclamation by Orders in Council 1606,[19][20] when the flags of Scotland and England were first merged to symbolise the Union of the Crowns.[21] (The Union of the Crowns having occurred in 1603). In Scotland, and in particular on Scottish vessels at sea, historical evidence suggests that a separate design of Union Flag was flown to that used in England.[22] In the Acts of Union of 1707, which united the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England to become the Kingdom of Great Britain, it was declared that "the Crosses of St. George and St. Andrew be conjoined, in such Manner as her Majesty shall think fit, and used in all Flags, Banners, Standards and Ensigns, both at Sea and Land."[23]

From 1801, to symbolise the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain with the Kingdom of Ireland, a new design which included St Patrick's Cross was adopted for the flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.[24] The Flag of the United Kingdom, having remained unchanged following the partition of Ireland in 1921 and creation of the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland, continues to be used as the flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

-

Saint George's Cross. In the Union Flag this represents the entire Kingdom of England, including Wales.

-

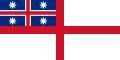

The English version of the First Union Flag, 1606, used mostly in England and, from 1707, the flag of the Kingdom of Great Britain.

-

The Scottish version of the First Union Flag saw limited use in Scotland from 1606 to 1707, following the Union of the Crowns.

-

The Second Union Flag, 1801, incorporating Cross of Saint Patrick, following Union of Great Britain and Kingdom of Ireland.

City of London

The flag of the City of London is based on the English flag, having a centred St George's Cross on a white background, with a red sword in the upper hoist canton (the top left quarter). The sword is believed to represent the sword that beheaded Saint Paul who is the patron saint of the city.[25]

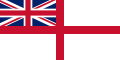

Royal Navy

The flag used by the British Royal Navy (the White Ensign) is also based on the flag of England, consisting of St George's Cross and a Union Flag in the canton. In addition to the United Kingdom, several countries in the Commonwealth of Nations also have variants of the White Ensign with their own national flags in the canton, with St George's Cross sometimes being replaced by a naval badge.[26]

Universities of England

-

Flag of the University of Bristol

-

Flag of the University of East Anglia

-

Flag of the University of Hull

-

Flag of the University of London

Contemporary use

Church of England

Churches belonging to the Church of England which have a pole may fly St George's Cross. A desirable variant (per an order from the Earl Marshal in 1938) is for the church to fly the flag with the arms of the diocese in the left-hand upper corner.[27]

-

Flag of the Diocese of Bath and Wells

-

Flag of the Diocese of Birmingham

-

Flag of the Diocese of Blackburn

-

Flag of the Diocese of Bristol

-

Flag of the Diocese of Canterbury

-

Flag of the Diocese of Carlisle

-

Flag of the Diocese of Chelmsford

-

Flag of the Diocese of Chester

-

Flag of the Diocese of Derby

-

Flag of the Diocese of Ely

-

Flag of the Diocese of Exeter

-

Flag of the Diocese of Gibraltar in Europe

-

Flag of the Diocese of Gloucester

-

Flag of the Diocese of Guildford

-

Flag of the Diocese of Hereford

-

Flag of the Diocese of Leeds

-

Flag of the Diocese of Leicester

-

Flag of the Diocese of Lichfield

-

Flag of the Diocese of Lincoln

-

Flag of the Diocese of London

-

Flag of the Diocese of Manchester

-

Flag of the Diocese of Newcastle

-

Flag of the Diocese of Norwich

-

Flag of the Diocese of Oxford

-

Flag of the Diocese of Portsmouth

-

Flag of the Diocese of Rochester

-

Flag of the Diocese of Salisbury

-

Flag of the Diocese of Sheffield

-

Flag of the Diocese of Southwark

-

Flag of the Diocese of Southwell and Nottingham

-

Flag of the Diocese of St Albans

-

Flag of the Diocese of Truro

-

Flag of the Diocese of Winchester

-

Flag of the Diocese of Worcester

Sporting events

The flag heavily dominates for that of England at sports events in which England competes, for example during England Cricket matches (the Cricket World Cup and The Ashes), during Rugby Union matches[28] and in football.[29] It is also used in icons on the internet and on the TV screen to represent teams and players from England.[citation needed]

For at least some decades before about 1996, most of the flags waved by supporters were Union Flags.[30] In a sporting context, the flag is often seen being waved by supporters with the addition of 'ENGLAND' across its horizontal bar.[citation needed]

English nationalism

As the flag of England, it is used in English nationalism. This is largely in parallel to the use of the flag of Scotland in Scottish nationalism. However Scotland has been recognised as a nation within a nation. The flag of Scotland has been officially defined by the Scottish Parliament in 2003 and is flown there and almost universally by Scottish authorities. There is no English legislature; the entire British legislature sits in England and is only subject to very weak conventions on voting on English matters. The flag of England does not figure in legislation, and its use by English nationalists is complex as these divide among those who are far-right as heavily opposed to further immigration and seeking to distinguish between residents in the jobs market and welfare state system such as the British National Party (founded 1982) and the English Defence League (founded 2009) and those who merely seek the level of devolution of Scotland, or Wales. Underscoring this complexity, in January 2012 Simon Hughes, the deputy leader of the Liberal Democrats, supported calls for a devolved English parliament and which continues under such lobbies as the Campaign for an English Parliament, and is occasionally a minor debate subject at all of the major parties' annual conferences.[31]

Since the flag's widespread use in sporting events since the mid-1990s, the association with far-right nationalism has waned, and the flag is now frequently flown throughout the country both privately and by local authorities.[32]

Outside England

Due to the spread of the British Empire, the flag of England is currently, and was formerly used on various flags and coats of arms of different countries, states and provinces throughout the territories of the British Empire. St George's Cross is also used as the city flag of some northern Italian cities, such as Milan and Bologna and other countries such as Georgia.

Australia

-

Flag of the governor of New South Wales, Australia

-

Queen Elizabeth II's personal Australian flag (1962–2022)

-

Lower Murray River Flag

-

Combined Murray River Flag

-

Flag of the Anglican Church of Australia

Canada

-

Flag of Montreal (1939–2017)

-

Flag of the Anglican Church of Canada

-

Flag of the Dominion of Canada (1868–1921)

-

Flag of the Hudson's Bay Company (1682–1707)

Channel Islands

-

Flag of Guernsey

(1936–1985)

Elsewhere

Commonly

-

Ulster Banner (Northern Ireland)

-

Flag of the New England Governor's Conference (NEGC)

-

Flag of Prince George's County, US (local, official uses)

-

Flag of Wellington, New Zealand

-

Flag of St. George's, Bermuda

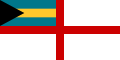

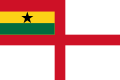

Navies

-

Naval Ensign of the Bahamas

Nautical, non-naval

-

Dunkirk Jack for all "little ships" which participated in the evacuation of 1940

-

Flag of the Portuguese Minister of Navy (1911 to 1974)

-

Sydney Ferries house flag

Rarely

-

Prime Minister of Jamaica

-

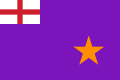

Flag of the Orange Order

-

Purple Standard, used by the Orange Order

-

Flag of the Grand Orange Lodge of New Zealand

-

Flag of the Loyal Orange Institution of Victoria

-

Flag of the governor of Saint Helena (official, local use)

-

Original flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand

-

Flag of New England (no official status but figures as a lower-order flag on a few official buildings)

-

Flag of Trinity College Dublin

Historically

-

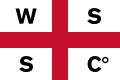

Flag of the East India Company (1600–1707)

-

Unofficial British Empire flag (1910–?)

-

Naval ensign of India (1950–2001)

-

Naval ensign of India (2004–2014)

-

Naval ensign of India (2014–2022)

-

Colonial flag of Jamaica

-

Former flag of the governor of Northern Ireland

-

Flag of the Loyalist Volunteer Force (legally declared a terrorist group and moribund/very low-level presence from 2000)

-

House flag of the British and Irish Steam Packet Company (B&I) dissolved 1992

-

House flag of the City of Cork Steam Packet Company (dissolved 1969)

-

House flag of the Cork Steamship Company (dissolved 1918)

-

House flag of the Limerick Steamship Company (dissolved 1970)

-

House flag of the Waterford Steamship Company (dissolved 1912)

-

Municipal flag of Prince George's County (1696–1963)

-

Queen Elizabeth II's personal Jamaican flag (1966–2022)

In Unicode

In 2017, the Unicode Consortium approved emoji support for the flag of England, alongside the flags of Scotland and Wales, in Unicode version 10.0 and Emoji version 5.0.[33][34] This was following a proposal from Jeremy Burge of Emojipedia and Owen Williams of BBC Wales in March 2016,[35][36] The flag is implemented using the regional indicator symbol sequence GB-ENG. Prior to this update, The Daily Telegraph reported that users had "been able to send emojis of the Union Flag, but not of the individual nations".[37]

See also

- Royal Banner of England

- Royal coat of arms of England

- List of English flags

- List of British flags

- Saint Patrick's Flag

- Tudor Rose

- Flags of Europe

- Flags of the English Interregnum

- St George's Day in England

- Flag of Georgia (country)

References

- ^ England (United Kingdom) Archived 28 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine; Gallery of sovereign state flags "The...proportion for the national flag of England is 3:5, with the each [limb of] the cross being 1⁄5 of the flag's height. The same ratio is used for Scotland and Wales. The saltire on Scotland's flag is [the same width]. It was chosen as being the closest 'standard' shape to the golden rectangle. Rectangular naval rank flags are actually 2:3, with the cross [each limb] being 1⁄6 of the height of the flag." Graham Bartram, 5 April 1999

- ^ Suchenia, Agnieszka (13 March 2013), The Union Flag and Flags of the United Kingdom (PDF), House of Commons Library, pp. 6–8

- ^ "What are the flags of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland?". Metro. 23 April 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ The Tudor naval streamer was a long, tapering flag, flown from the top of the forecastle, from 20 up to 60 yards in length. "A streamer shall stand in the toppe of a shippe, or in the forecastle, and therein be putt no armes, but a man's conceit or device, and may be of the lengthe of twenty, forty, or sixty yards." – Harleian MS 2358 on the Syze of Banners, Standardes, Pennons, Guydhomes, Pencels, and Streamers (cited after Frederick Edward Hulme, The Flags of the World (1896), p. 26).

- ^ E.g. "Richard Coeur de Lion embarked on Genoese galleys under their banner of the Red Cross and the flag of St. George, which he brought home to become the patron of Old England". The Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society, Volumes 7–8, 1891, p. 139. There are variants; in another version Richard is impressed with the Genoese at Acre.

- ^ "I have been unable to find any solid ground for the common belief that the cross of St George was introduced as the national emblem of England by Richard I, and am of opinion that it did not begin to attain that position until the first years of the reign of Edward I". (Perrin 1922, p. 15)

- ^ This version was taken at face value on the website of a "Ligurian Independence Movement", presented by Vincenzo Matteucci in an article entitled L'Inghilterra "pagava" per poter innalzare la bandiera della gloriosa Repubblica di Genova sulle sue navi! ("England paid for flying on its ships the banner of the Glorious Republic of Genoa!") on that website (Movimento Indipendentista Ligure 7 No. 3/4 2002), and posted on flags of the world.

- ^ a b Genoa page at Flags of the World by ed. Filippo Noceti, 2001

- ^ "Australian Flag – 21/04/1993 – ADJ". NSW Parliament. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ Perrin 1922, p. 37

- ^ Curry, Anne (2000). The Battle of Agincourt: Sources and Interpretations. Boydell Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-85115-802-0.

- ^ Perrin 1922, p. 37

- ^ "Among the greater banners that of St George was not as yet supreme; it was indeed only one of four, for when the Castle of Carlaverock was taken in the year 1300: Puis fist le roy porter amont / Sa baniere et la Seint Eymont / La Seint George et la Seint Edwart [...]" (Perrin 1922, p. 37)

- ^ "The first step towards the promotion of St George to a position of predominance seems to be due to Edward III, who in gratitude for his supposed help at the Battle of Crecy founded the Chapel of St George at Windsor in 1348." (Perrin 1922, pp. 37f.)

- ^ It was first introduced as a minor feast day observed in the Church of England in 1222, but its omission from later lists suggests that it was not universally adopted. (Perrin 1922, p. 38).

- ^ "When the Prayer Book was revised under Edward VI (1547–1553), the festival of St George was abolished, with many others. Under the influence of the Reformation the banners of his former rivals, St Edward and St Edmund, together with all other religious flags in public use, except that of St George, entirely disappeared, and their place was taken by banners containing royal badges" (W. G. Perrin (1922). British Flags. Cambridge University Press. p. 40).

- ^ The Life of King Henry V Act 3, end of Scene 1 France. Before Harfleur...with scaling ladders, William Shakespeare, Project Gutenburg, Release Date: November, 1998 [eBook #1521]

- ^ G. K. Chesterton (1933). Christendom in Dublin. p. 9.

- ^ Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1904) [1986]. The Art of Heraldry: An Encyclopædia of Armory. London: Bloomsbury Books. p. 399. ISBN 0-906223-34-2.

- ^ Royal Website Archived 30 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Flag Institute

- ^ Flags of the World Scotland

- ^ "Act of Union (Article 1)". Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ^ Flags of the World GB history

- ^ City of London Archived 23 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Britishflags.net

- ^ "United Kingdom: history of the British ensigns". Fotw.net. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- ^ Church of England – Use of the flag; Flags of the World; 23 October 2008

- ^ England Rugby Football Union Archived 23 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 2010 FIFA World Cup

- ^ "The Saturday Soap Box: We have to make Jerusalem England's national anthem". Daily Mirror. 17 September 2005. Archived from the original on 11 October 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2006.

- ^ Barnes, Eddie (22 January 2012). "Scottish independence referendum: Liberal Democrats deputy leader Simon Hughes calls for English devolution". Scotland on Sunday. Edinburgh: Johnston Publishing Ltd. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ Conn, David; Sour English stereotypes linger amid the flag-waving; The Guardian; 12 July 2006

- ^ Thomas, Huw (5 August 2016). "Wales flag emoji decision awaited". BBC News. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Titcomb, James (2017). "Emoji for England, Scotland and Wales flags to be released this year". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Huw (5 August 2016). "Wales flag emoji decision awaited". BBC News. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Titcomb, James (2017). "Emoji for England, Scotland and Wales flags to be released this year". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "Flags of England, Wales and Scotland given thumbs up by emoji chiefs". The Daily Telegraph. 11 December 2016. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

External links

- "United Kingdom Flag History". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Flag of England at Flags of the World