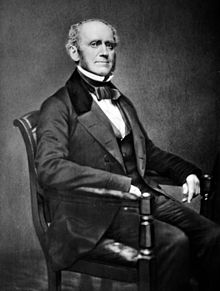

Fitz-Greene Halleck

Fitz-Greene Halleck | |

|---|---|

Fitz-Greene Halleck | |

| Born | July 8, 1790 Guilford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | November 19, 1867 (aged 77) Guilford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet |

Fitz-Greene Halleck (July 8, 1790 – November 19, 1867) was an American poet and member of the Knickerbocker Group. Born and raised in Guilford, Connecticut, he went to New York City at the age of 20, and lived and worked there for nearly four decades. He was sometimes called "the American Byron". His poetry was popular and widely read but later fell out of favor. It has been studied since the late twentieth century for its homosexual themes and insights into nineteenth-century society.

In 1832, Halleck, a cultural celebrity, started working as personal secretary and adviser to the philanthropist John Jacob Astor, who appointed him as one of the original trustees of the Astor Library. Given an annuity by Astor's estate, in 1849 Halleck retired to Guilford, where he lived with his sister Marie Halleck for the remainder of his life.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Fitz-Greene Halleck was born on July 8, 1790,[1] in Guilford, Connecticut, in a house at the corner of Whitfield and Water Streets.[2] He had an older sister Marie, and his father owned a store in the town. At the age of two, the young Halleck experienced hearing loss when two soldiers fired off their guns next to his left ear; he was partially deaf for the remainder of his life.[3] As a boy, Halleck attended the Academy on Guilford Green, whose schoolmaster was then Samuel Johnson, Junior, the compiler of A School Dictionary, the first dictionary both compiled and published in the United States. Halleck was a favorite of Johnson, who gave him a copy of Thomas Campbell's first book of poems, The Pleasures of Hope,[4] which was Halleck's first personal book.[5] He left school at 15 to work in his family's shop in Guilford.

Early career

[edit]In May 1811, the 20-year-old Halleck moved to New York City to find work. After a month of searching, he had all but given up and made plans to move to Richmond, Virginia, but he was hired by a banker named Jacob Barker.[6] He worked for Barker for the next 20 years.

Halleck began to write with his friend Joseph Rodman Drake. In 1819 they wrote and published the anonymous Croaker Papers, which were satires of New York society. These 35 poems were published individually in the New York Evening Post and National Advertiser over several months. An unauthorized collection was published in 1819 with 24 selections. They published the poems under the pseudonyms Croaker; Croaker, Jr.; and Croaker and Co., taken from a character in Oliver Goldsmith's The Good‐Natured Man.[7] The "Croakers" were perhaps the first popular literary satire of New York, and New York society was thrilled to be the subject of erudite derision.

That year, Halleck wrote his longest poem Fanny, a satire on the literature, fashions, and politics of the time. It was modeled on Lord Byron's Beppo and Don Juan.[7] Published anonymously in December 1819, Fanny proved so popular that soon the initial 50 cent-edition was fetching up to $10. Two years later, its continuing popularity inspired Halleck to append an additional 50 stanzas.[8]

Both Halleck and Drake became associated with the New York writers known as the Knickerbocker Group, led by William Cullen Bryant, James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving, pioneers in their fields. Drake advised Halleck to pursue becoming a nationally known poet and to sit on "Appalachia's brow." He thought contemplating the immense power of American nature would inspire his friend's imagination.[9] A medical student, Drake died in 1820 of consumption (tuberculosis) at age 25. Halleck commemorated his friend in "The Death of Joseph Rodman Drake" (1820), which begins, "Green be the turf above thee".[10]

Sarah Eckford Drake, the student's young widow, was left with their daughter. She showed interest in having Halleck as her second husband. His satires included her as a figure, and in one he referred to her as a witch. She died young in 1828.[10] Halleck never married.

In 1822, Halleck visited Europe and Great Britain, which influenced his poetry. "Alnwick Castle" was written that year and refers to a stately home in Northumberland. His long poem Marco Bozzaris (1825) was dedicated to the heroic Greek freedom fighter against the Turks, showing the continuing influence of Byron's example. In 1827 Halleck published a collection, Alnwick Castle, with Other Poems, but after that his writing decreased.[7]

Professional and later life

[edit]By 1830 Halleck had become a kind of celebrity for his poetry, sometimes called the American Byron.[11] In 1832, Halleck was hired as the private secretary to John Jacob Astor. The wealthy fur trader merchant turned philanthropist later appointed him as one of the original trustees of the Astor Library (the basis of the New York Public Library). Halleck also served as Astor's cultural tutor, advising him on pieces of art to purchase.

During this period, Halleck was widely read and was part of New York literary society. As one of the younger members of the Knickerbocker Group, he published with them and met associated visiting writers, such as Charles Dickens. His satires were thought to challenge the era's "sacred institutions" and Halleck was known for his wit and charm.[11]

At Astor's death, the immensely wealthy—and tightfisted—man left Halleck an annuity in his will: of only $200 annually. His son William increased the amount to $1,500.

In 1841 he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Honorary Academician.

In 1849 Halleck retired to his hometown of Guilford. There he lived with his unmarried sister Marie Halleck for the remainder of his life. In April 1860, a lingering illness made Halleck give instructions for his funeral and burial, but he recovered.[12] He often turned down requests for public appearances in his later years, and he complained about being pestered by "frequent appeals for letters to hard-hearted editors".[13] When people named children after him, Halleck seemed annoyed rather than honored. He wrote, "I am favored by affectionate fathers with epistles announcing that their eldest-born has been named after me, a calamity that costs me a letter of profound gratefulness".[13] Halleck's last major poem, "Young America", was published in 1867 in the New York Ledger.[3]

On November 19, 1867, around 11:00 at night, he called out to his sister, "Marie, hand me my pantaloons, if you please." He died without making another sound before she could turn around.[14] He is buried at Alderbrook Cemetery in Guilford.[15]

Sexuality

[edit]Halleck never married. His biographer Hallock believes that he was homosexual. He found that Halleck was enamored at the age of 19 with a young Cuban named Carlos Menie, to whom he dedicated a few of his early poems.[16] Hallock suggests that Halleck was in love with his friend Joseph Rodman Drake. James Grant Wilson noted how the poet described serving as best man at Drake's wedding:

"[Drake] has married, and, as his wife's father is rich, I imagine he will write no more. He was poor, as poets, of course, always are, and offered himself a sacrifice at the shrine of Hymen to shun the 'pains and penalties' of poverty. I officiated as groomsman, though much against my will. His wife was good natured, and loves him to distraction. He is perhaps the handsomest man in New York, — a face like an angel, a form like an Apollo; and, as I well knew that his person was the true index of his mind, I felt myself during the ceremony as committing a crime in aiding and assisting such a sacrifice."[17]

Hallock described the poet Halleck's last major work, "Young America", as both "a jaded critique of marriage and a pederastic boy-worship reminiscent of classical homosexuality."[3]

In his will Halleck asked for Drake's body and family to be exhumed and reburied with him.[18] In 1903, plans were set to move the bodies of Drake, his wife, daughter, sister, and nephew to Halleck's plot in Guilford.[19]

Critical response

[edit]In the mid to late 19th century, Halleck was regarded as one of America's leading poets and had a wide general readership; he was dubbed "the American Byron". Among his most well-known poems was "Marco Bozzaris", which Halleck noted was "puffed in a thousand (more or less) magazines and newspapers" in the United States, England, Scotland, and Ireland.[20] Charles Dickens spoke fondly of the "accomplished writer" in a January 1868 letter to William Makepeace Thackeray (as recounted in Thackeray in the United States). It is not clear whether Dickens admired Halleck's poetic skills or his wit and charm, which was often lauded by his contemporaries. Abraham Lincoln was known to occasionally read Halleck's poetry aloud to friends in the White House.

The American writer and critic Edgar Allan Poe reviewed Halleck's poetry collection Alnwick Castle. Regarding Halleck's poem "Fanny", he said, "to uncultivated ears... [it is] endurable, but to the practiced versifier it is little less than torture."[21] In the September 1843 issue of Graham's Magazine, Poe wrote that Halleck "has nearly abandoned the Muses, much to the regret of his friends and to the neglect of his reputation."[21] However, Poe also wrote, "No name in the American poetical world is more firmly established than that of Fitz-Greene Halleck."

Halleck had several years in which he did not produce any literary works. After his death, poet William Cullen Bryant addressed the New York Historical Society on February 2, 1869, and spoke about this blank period in Halleck's career. He ultimately concluded: "Whatever the reason that Halleck ceased so early to write, let us congratulate ourselves that he wrote at all."[22]

Since the later 20th century, Halleck's poetry has been studied for its homosexual themes, and for what it reveals about the social world of the nineteenth century.

Legacy

[edit]

- In 1869, the collected Poetical Writings and a traditional Life and Letters, both edited and written by James Grant Wilson, were published.[23]

- Also in 1869, a granite monument was erected to Halleck in Guilford, the first to memorialize an American poet. The writer Bayard Taylor spoke at the commemoration. Taylor wrote America's first homosexual novel, Joseph and His Friend (1870), believed to be a fictional account of the relationship between Halleck and Drake.[24]

- In 1877 the memorial statue of Halleck was erected in New York's Central Park; Halleck is the only American writer on the Literary Walk. It was dedicated by President Rutherford B. Hayes, with 10,000 people attending. After that, requirements for memorial statues in the park became more stringent.[25]

- In 2006 the Fitz-Greene Halleck Society was founded to raise awareness of him and his work.

Works

[edit]- Croaker Papers (1819), complete edition, 1860[7]

- Marco Bozzaris (1825)

- Alnwick Castle, with Other Poems (1827)

Further reading

[edit]- Wilson, James Grant, The Life and Letters of Fitz-Greene Halleck (New York, 1869).

- Wilson, James Grant, The Poetical Writings of Fitz-Greene Halleck (New York, 1869).

- Nelson Frederick Adkins, Fitz-Greene Halleck: An Early Knickerbocker Wit and Poet (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1930).

- Hallock, John Wesley Matthew. "The First Statue: Fitz-Greene Halleck and Homotextual Representation in Nineteenth-Century America." Ph.D. Dissertation, Temple University; DAI, Vol. 58-06A (1997): 2209, Temple University.

- Hallock, John Wesley Matthew, American Byron: Homosexuality & The Fall Of Fitz-Greene Halleck (Madison, Wisconsin: U. of Wisconsin Press, 2000).

Notes

[edit]- ^ Nelson, Randy F. The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc., 1981: 44. ISBN 0-86576-008-X

- ^ Ehrlich & Carruth, 76

- ^ a b c Hallock, 9

- ^ Campbell, Thomas (1800). The Pleasures of Hope. New York: John Furman.

- ^ Wilson, James Grant (1869). The Life and Letters of Fitz-Greene Halleck. New York: D. Appleton & Company. p. 52.

- ^ Hallock, 43

- ^ a b c d James D. Hart and Phillip W. Leininger. "Croaker Papers," in The Oxford Companion to American Literature', 1995

- ^ Burt, Daniel S. The Chronology of American Literature: America's Literary Achievements From the Colonial Era to Modern Times. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2004: 126. ISBN 978-0-618-16821-7

- ^ Callow, James T. Kindred Spirits: Knickerbocker Writers and American Artists, 1807–1855. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1967: 147

- ^ a b Hallock, 90–92

- ^ a b Hallock

- ^ Hallock, 142

- ^ a b Hallock, 143

- ^ Hallock, 150

- ^ Ehrlich & Carruth, 77

- ^ Hallock, 32

- ^ James Grant Wilson, The Life and Letters of Fitz-Greene Halleck. New York: Appleton and Company, 1869: 184.

- ^ "To Exhume Drake's Body". New York Times. September 19, 1903.

- ^ Hallock, 91

- ^ Hallock, 97

- ^ a b Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books, 2001: 103. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X

- ^ Chubb, Edwin Watts. Stories of Authors, British & American. Echo Library, 2008: 152. ISBN 978-1-4068-9253-6

- ^ Charley Shively, "Review of Hallock's 'The American Byron'", Biography, Vol. 24, Number 3, Summer 2001, accessed 30 May 2011

- ^ Hallock, 151

- ^ Michael Pollak, "A Faded Literary Light", New York Times, 5 September 2004

References

[edit]- Ehrlich, Eugene and Gorton Carruth. The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982. ISBN 0-19-503186-5

- Hallock, John W. M. The American Byron: Homosexuality and the Fall of Fitz-Greene Halleck. University of Wisconsin Press, 2000. ISBN 0-299-16804-2

External links

[edit]- Works by Fitz-Greene Halleck at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Fitz-Greene Halleck at the Internet Archive

- Halleck in Central Park Archived 2015-09-05 at the Wayback Machine, by Central Park Conservancy

- Fitz-Greene Halleck biography, Lehigh University digital library

- The Fitz-Greene Halleck Society