Meta Platforms

Logo since 2021 | |

Headquarters in Menlo Park, California | |

| Meta | |

| Formerly |

|

| Company type | Public |

| |

| Industry | |

| Founded | January 4, 2004 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owner | Mark Zuckerberg (13.68% equity; 61.2% voting)[1] |

Number of employees | 74,067 (Dec. 2024) |

| Divisions | Reality Labs |

| Subsidiaries | Novi Financial |

| ASN | |

| Website | meta.com |

| Footnotes / references [2][3][4][5][6][7][8] | |

Meta Platforms, Inc.,[9] doing business as Meta,[10] and formerly named Facebook, Inc., and TheFacebook, Inc.,[11][12] is an American multinational technology conglomerate based in Menlo Park, California. The company owns and operates Facebook, Instagram, Threads, and WhatsApp, among other products and services.[13] Advertising accounts for 97.8 percent of its revenue.[a][14] Originally known as the parent company of the Facebook service, as Facebook, Inc., it was rebranded to its current name in 2021 to "reflect its focus on building the metaverse",[15] an integrated environment linking the company's products and services.[16][17][18]

Meta ranks among the largest American information technology companies, alongside other Big Five corporations Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft. The company was ranked #31 on the Forbes Global 2000 ranking in 2023.[19] In 2022, Meta was the company with the third-highest expenditure on research and development worldwide, with R&D expenditure amounting to US$35.3 billion.[20] Meta has also acquired Oculus (which it has integrated into Reality Labs), Mapillary, CTRL-Labs, and a 9.99% stake in Jio Platforms; the company additionally endeavored into non-VR hardware, such as the discontinued Meta Portal smart displays line and partners with Luxottica through the Ray-Ban Stories series of smartglasses.[21][22]

History

| This article is part of a series about |

| Meta Platforms |

|---|

|

| Products and services |

| People |

| Business |

Facebook filed for an initial public offering (IPO) on January 1, 2012.[23] The preliminary prospectus stated that the company sought to raise $5 billion, had 845 million monthly active users, and a website accruing 2.7 billion likes and comments daily.[24] After the IPO, Zuckerberg would retain 22% of the total shares and 57% of the total voting power in Facebook.[25]

Underwriters valued the shares at $38 each, valuing the company at $104 billion, the largest valuation yet for a newly public company.[26] On May 16, one day before the IPO, Facebook announced it would sell 25% more shares than originally planned due to high demand.[27] The IPO raised $16 billion, making it the third-largest in US history (slightly ahead of AT&T Mobility and behind only General Motors and Visa). The stock price left the company with a higher market capitalization than all but a few U.S. corporations—surpassing heavyweights such as Amazon, McDonald's, Disney, and Kraft Foods—and made Zuckerberg's stock worth $19 billion.[28][29] The New York Times stated that the offering overcame questions about Facebook's difficulties in attracting advertisers to transform the company into a "must-own stock". Jimmy Lee of JPMorgan Chase described it as "the next great blue-chip".[28] Writers at TechCrunch, on the other hand, expressed skepticism, stating, "That's a big multiple to live up to, and Facebook will likely need to add bold new revenue streams to justify the mammoth valuation."[30]

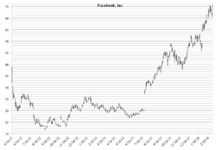

Trading in the stock, which began on May 18, was delayed that day due to technical problems with the Nasdaq exchange.[31] The stock struggled to stay above the IPO price for most of the day, forcing underwriters to buy back shares to support the price.[32] At the closing bell, shares were valued at $38.23,[33] only $0.23 above the IPO price and down $3.82 from the opening bell value. The opening was widely described by the financial press as a disappointment.[34] The stock nonetheless set a new record for trading volume of an IPO.[35] On May 25, 2012, the stock ended its first full week of trading at $31.91, a 16.5% decline.[36]

On May 22, 2012, regulators from Wall Street's Financial Industry Regulatory Authority announced that they had begun to investigate whether banks underwriting Facebook had improperly shared information only with select clients rather than the general public. Massachusetts Secretary of State William F. Galvin subpoenaed Morgan Stanley over the same issue.[37] The allegations sparked "fury" among some investors and led to the immediate filing of several lawsuits, one of them a class action suit claiming more than $2.5 billion in losses due to the IPO.[38] Bloomberg estimated that retail investors may have lost approximately $630 million on Facebook stock since its debut.[39] S&P Global Ratings added Facebook to its S&P 500 index on December 21, 2013.[40]

On May 2, 2014, Zuckerberg announced that the company would be changing its internal motto from "Move fast and break things" to "Move fast with stable infrastructure".[41][42] The earlier motto had been described as Zuckerberg's "prime directive to his developers and team" in a 2009 interview in Business Insider, in which he also said, "Unless you are breaking stuff, you are not moving fast enough."[43]

2018–2020: Focus on the metaverse

Lasso was a short-video sharing app from Facebook similar to TikTok that was launched on iOS and Android in 2018 and was aimed at teenagers. On July 2, 2020, Facebook announced that Lasso would be shutting down on July 10.[44][45][46]

In 2018, the Oculus lead Jason Rubin sent his 50-page vision document titled "The Metaverse" to Facebook's leadership. In the document, Rubin acknowledged that Facebook's virtual reality business had not caught on as expected, despite the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on content for early adopters. He also urged the company to execute fast and invest heavily in the vision, to shut out HTC, Apple, Google and other competitors in the VR space. Regarding other players' participation in the metaverse vision, he called for the company to build the "metaverse" to prevent their competitors from "being in the VR business in a meaningful way at all".[47]

In May 2019, Facebook founded Libra Networks, reportedly to develop their own stablecoin cryptocurrency.[48] Later, it was reported that Libra was being supported by financial companies such as Visa, Mastercard, PayPal and Uber. The consortium of companies was expected to pool in $10 million each to fund the launch of the cryptocurrency coin named Libra.[49] Depending on when it would receive approval from the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory authority to operate as a payments service, the Libra Association had planned to launch a limited format cryptocurrency in 2021.[50] Libra was renamed Diem, before being shut down and sold in January 2022 after backlash from Swiss government regulators and the public.[51][52]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of online services, including Facebook, grew globally.[53] Zuckerberg predicted this would be a "permanent acceleration" that would continue after the pandemic. Facebook hired aggressively, growing from 48,268 employees in March 2020 to more than 87,000 by September 2022.[53]

2021: Rebrand as Meta

Following a period of intense scrutiny and damaging whistleblower leaks, news started to emerge on October 21, 2021, about Facebook's plan to rebrand the company and change its name.[15][54] In the Q3 2021 Earnings Call on October 25, Mark Zuckerberg discussed the ongoing criticism of the company's social services and the way it operates, and pointed to the pivoting efforts to building the metaverse – without mentioning the rebranding and the name change.[55] The metaverse vision and the name change from Facebook, Inc. to Meta Platforms was introduced at Facebook Connect on October 28, 2021.[16] Based on Facebook's PR campaign, the name change reflects the company's shifting long term focus of building the metaverse, a digital extension of the physical world by social media, virtual reality and augmented reality features.[16][56]

"Meta" had been registered as a trademark in the United States in 2018 (after an initial filing in 2015) for marketing, advertising, and computer services, by a Canadian company that provided big data analysis of scientific literature.[57] This company was acquired in 2017 by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI), a foundation established by Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, and became one of their projects.[58] Following the rebranding announcement, CZI announced that it had already decided to deprioritize the earlier Meta project, thus it would be transferring its rights to the name to Meta Platforms, and the previous project would end in 2022.[59]

2022: Declining profits and mass lay-offs

Soon after the rebranding, in early February 2022, Meta reported a greater-than-expected decline in profits in the fourth quarter of 2021.[60] It reported no growth in monthly users,[61] and indicated it expected revenue growth to stall.[60] It also expected measures taken by Apple Inc. to protect user privacy to cost it some $10 billion in advertisement revenue, an amount equal to roughly 8% of its revenue for 2021.[62] In meeting with Meta staff the day after earnings were reported, Zuckerberg blamed competition for user attention, particularly from video-based apps such as TikTok.[63]

The 27% reduction in the company's share price which occurred in reaction to the news eliminated some $230 billion of value from Meta's market capitalization.[61] Bloomberg described the decline as "an epic rout that, in its sheer scale, is unlike anything Wall Street or Silicon Valley has ever seen".[61] Zuckerberg's net worth fell by as much as $31 billion.[64] Zuckerberg owns 13% of Meta, and the holding makes up the bulk of his wealth.[65][66]

According to published reports by Bloomberg on March 30, 2022, Meta turned over data such as phone numbers, physical addresses, and IP addresses to hackers posing as law enforcement officials using forged documents. The law enforcement requests sometimes included forged signatures of real or fictional officials. When asked about the allegations, a Meta representative said, "We review every data request for legal sufficiency and use advanced systems and processes to validate law enforcement requests and detect abuse."[67] In June 2022, Sheryl Sandberg, the chief operating officer of 14 years, announced she would step down that year. Zuckerberg said that Javier Olivan would replace Sandberg, though in a “more traditional” role.[68]

In March 2022, Meta (except Meta-owned WhatsApp) and Instagram were banned in Russia and added to Russian list of terrorist and extremist organizations for alleged Russophobia and hate speech (up to genocidal calls) amid ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine.[69] Meta appealed against the ban, but it was upheld by a Moscow court in June of the same year.[69]

Also in March 2022, Meta and Italian eyewear giant Luxottica released Ray-Ban Stories, a series of smartglasses which could play music and take pictures. Meta and Luxottica parent company EssilorLuxottica declined to disclose sales on the line of products as of September 2022, though Meta has expressed satisfaction with its customer feedback.[22][70][71]

In July 2022, Meta saw its first year-on-year revenue decline when its total revenue slipped by 1% to $28.8bn.[72] Analysts and journalists accredited the loss to its advertising business, which has been limited by Apple's app tracking transparency feature and the number of people who have opted not to be tracked by Meta apps. Zuckerberg also accredited the decline to increasing competition from TikTok.[73][74][75] On October 27, 2022, Meta's market value dropped to $268 billion, a loss of around $700 billion compared to 2021, and its shares fell by 24%. It lost its spot among the top 20 US companies by market cap, despite reaching the top 5 in the previous year.[76]

In November 2022, Meta laid off 11,000 employees, 13% of its workforce. Zuckerberg said the decision to aggressively increase Meta's investments had been a mistake, as he had wrongly predicted that the surge in e-commerce would last beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. He also attributed the decline to increased competition, a global economic downturn and "ads signal loss".[77] Plans to lay off a further 10,000 employees began in April 2023.[78] The layoffs were part of a general downturn in the technology industry, alongside layoffs by companies including Google, Amazon, Tesla, Snap, Twitter and Lyft.[79][80]

Starting from 2022, Meta scrambled to catch up to other tech companies in adopting specialized artificial intelligence hardware and software. It had been using less expensive CPUs instead of GPUs for AI work, but that approach turned out to be less efficient.[81]

Since 2023: Threads, AI and all-time high stock value

In 2023, Ireland's Data Protection Commissioner imposed a record EUR 1.2 billion fine on Meta for transferring data from Europe to the United States without adequate protections for EU citizens.[82]: 250

In March 2023, Meta announced a new round of layoffs that would cut 10,000 employees and close 5,000 open positions to make the company more efficient.[83] Meta revenue surpassed analyst expectations for the first quarter of 2023 after announcing that it was increasing its focus on AI.[84] On July 6, Meta launched a new app, Threads, a competitor to Twitter.[85]

Meta announced its artificial intelligence model Llama 2 in July 2023, available for commercial use via partnerships with major cloud providers like Microsoft. It was the first project to be unveiled out of Meta's generative AI group after it was set up in February. It would not charge access or usage but instead operate with an open-source model to allow Meta to ascertain what improvements need to be made. Prior to this announcement, Meta said it had no plans to release Llama 2 for commercial use. An earlier version of Llama was released to academics.[86][87]

In August 2023, Meta announced its permanent removal of news content from Facebook and Instagram in Canada due to the Online News Act, which requires Canadian news outlets to be compensated for content shared on its platform. The Online News Act was in effect by year-end, but Meta will not participate in the regulatory process.[88] In October 2023, Zuckerberg said that AI would be Meta's biggest investment area in 2024.[89] Meta finished 2023 as one of the best-performing technology stocks of the year, with its share price up 150 percent.[90] Its stock reached an all-time high in January 2024, bringing Meta within 2% of achieving $1 trillion market capitalization.[91]

Meta Platforms launched an ad-free service in Europe in November 2023, allowing subscribers to opt-out of personal data being collected for targeted advertising. A group of 28 European organizations, including Max Schrems' advocacy group NOYB, the Irish Council for Civil Liberties, Wikimedia Europe, and the Electronic Privacy Information Center, signed a 2024 letter to the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) expressing concern that this subscriber model would undermine privacy protections, specifically GDPR data protection standards.[92]

Meta removed the Facebook and Instagram accounts of Iran's Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in February 2024, citing repeated violations of its Dangerous Organizations & Individuals policy.[93] As of March, Meta was under the investigation of the FDA for alleged use of their social media platforms to sell illegal drugs.[94] On 16 May 2024, the European Commission began an investigation into Meta over concerns related to child safety.[95][96][97][98]

In May 2023, Iraqi social media influencer Esaa Ahmed-Adnan encountered a troubling issue when Instagram removed his posts, citing false copyright violations despite his content being original and free from copyrighted material. He discovered that extortionists were behind these takedowns, offering to restore his content for $3,000 or provide ongoing protection for $1,000 per month. This scam, exploiting Meta’s rights management tools, became widespread in the Middle East, revealing a gap in Meta’s enforcement in developing regions. An Iraqi nonprofit Tech4Peace’s founder, Aws al-Saadi helped Ahmed-Adnan and others, but the restoration process was slow, leading to significant financial losses for many victims, including prominent figures like Ammar al-Hakim. This situation highlighted Meta’s challenges in balancing global growth with effective content moderation and protection.[99]

On 16 September 2024, Meta announced it had banned Russian state media outlets from its platforms worldwide due to concerns about "foreign interference activity." This decision followed allegations that RT and its employees funneled $10 million through shell companies to secretly fund influence campaigns on various social media channels. Meta's actions were part of a broader effort to counter Russian covert influence operations, which had intensified since the invasion.[100]

At its 2024 Connect conference, Meta presented Orion,[101] its first pair of augmented reality glasses. Though Orion was originally intended to be sold to consumers, the manufacturing process turned out to be too complex and expensive.[102] Instead, the company pivoted to producing a small number of the glasses to be used internally.[103]

On 4 October 2024, Meta announced about its new AI model called Movie Gen, capable of generating realistic video and audio clips based on user prompts. Meta stated it would not release Movie Gen for open development, preferring to collaborate directly with content creators and integrate it into its products by the following year. The model was built using a combination of licensed and publicly available datasets.[104]

On October 31, 2024, ProPublica published an investigation into deceptive political advertisement scams that sometimes use hundreds of hijacked profiles and facebook pages run by organized networks of scammers. The authors cited spotty enforcement by Meta as a major reason for the extent of the issue.[105]

In November 2024, TechCrunch reported that Meta were considering building a $10bn global underwater cable spanning 25,000 miles.[106]

In the same month, Meta closed down 2 million accounts on Facebook and Instagram that were linked to scam centers in Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, the Philippines, and the United Arab Emirates doing pig butchering scams.[107]

In December 2024, Meta announced that, beginning February 2025, they would require advertisers to run ads about financial services in Australia to verify information about who are the beneficiary and the payer in a bid to regulate scams.[108]

On December 4, 2024, Meta announced it will invest $10 billion USD for its largest AI data center in northeast Louisiana, powered by natural gas facilities. [109]

On the 11th of that month, Meta experienced a global outage, impacting accounts on all of their social media and messaging applications. Outage reports from DownDetector reached 70,000+ and 100,000+ within minutes for Instagram and Facebook, respectively.[110] On X, Meta's official account responded to reports stating they were aware of the technical issue and were working to combat it.[1]

Mergers and acquisitions

Meta has acquired multiple companies (often identified as talent acquisitions).[111] One of its first major acquisitions was in April 2012, when it acquired Instagram for approximately US$1 billion in cash and stock.[112] In October 2013, Facebook, Inc. acquired Onavo, an Israeli mobile web analytics company.[113][114] In February 2014, Facebook, Inc. announced it would buy mobile messaging company WhatsApp for US$19 billion in cash and stock.[115][116] Later that year, Facebook bought Oculus VR for $2.3 billion in cash and stock,[117] which released its first consumer virtual reality headset in 2016. In late November 2019, Facebook, Inc. announced the acquisition of the game developer Beat Games, responsible for developing one of that year's most popular VR games, Beat Saber.[118] In Late 2022, after Facebook Inc rebranded to Meta Platforms Inc, Oculus was rebranded to Meta Quest.

In May 2020, Facebook, Inc. announced it had acquired Giphy for a reported cash price of $400 million. It will be integrated with the Instagram team.[119] However, in August 2021, UK's Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) stated that Facebook, Inc. might have to sell Giphy, after an investigation found that the deal between the two companies would harm competition in display advertising market.[120] Facebook, Inc. was fined $70 million by CMA for deliberately failing to report all information regarding the acquisition and the ongoing antitrust investigation.[121] In October 2022, the CMA ruled for a second time that Meta be required to divest Giphy, stating that Meta already controls half of the advertising in the UK. Meta agreed to the sale, though it stated that it disagrees with the decision itself.[122] In May 2023, Giphy was divested to Shutterstock for $53 million.[123]

In November 2020, Facebook, Inc. announced that it planned to purchase the customer-service platform and chatbot specialist startup Kustomer to promote companies to use their platform for business. It has been reported that Kustomer valued at slightly over $1 billion.[124] The deal was closed in February 2022 after regulatory approval.[125]

In September 2022, Meta acquired Lofelt, a Berlin-based haptic tech startup.[126]

Lobbying

In 2020, Facebook, Inc. spent $19.7 million on lobbying, hiring 79 lobbyists. In 2019, it had spent $16.7 million on lobbying and had a team of 71 lobbyists, up from $12.6 million and 51 lobbyists in 2018.[127] Facebook was the largest spender of lobbying money among the Big Tech companies in 2020.[128] The lobbying team includes top congressional aide John Branscome, who was hired in September 2021, to help the company fend off threats from Democratic lawmakers and the Biden administration.[129]

In December 2024, Meta donated $1 million to the inauguration fund for then-President-elect Donald Trump.[130]

Censorship

In August 2024, Mark Zuckerberg sent a letter to Jim Jordan indicating that during the COVID-19 pandemic the Biden administration repeatedly asked Meta to limit certain COVID-19 content, including humor and satire, on Facebook and Instagram.[131]

In 2016, Meta hired Jordana Cutler, formerly an employee at the Israeli Embassy to the United States, as its policy chief for Israel and the Jewish Diaspora. In this role, Cutler pushed for the censorship of accounts belonging to Students for Justice in Palestine chapters in the United States. Critics have said that Cutler's position gives the Israeli government an undue influence over Meta policy, and that few countries have such high levels of contact with Meta policymakers.[132]

Following the election of Donald Trump in 2025, various sources noted possible censorship related to the Democratic Party on Instagram and other Meta platforms.[133][134][135]

Disinformation concerns

Since its inception, Meta has been accused of being a host for fake news and misinformation.[136] In the wake of the 2016 United States presidential election, Zuckerberg began to take steps to eliminate the prevalence of fake news, as the platform had been criticized for its potential influence on the outcome of the election.[137] The company initially partnered with ABC News, the Associated Press, FactCheck.org, Snopes and PolitiFact for its fact-checking initiative;[138] as of 2018, it had over 40 fact-checking partners across the world, including The Weekly Standard.[53]

A May 2017 review by The Guardian found that the platform's fact-checking initiatives of partnering with third-party fact-checkers and publicly flagging fake news were regularly ineffective, and appeared to be having minimal impact in some cases.[139] In 2018, journalists working as fact-checkers for the company criticized the partnership, stating that it had produced minimal results and that the company had ignored their concerns.[53]

In 2024 Meta's decision to continue to disseminate a falsified video of US president Joe Biden, even after it had been proven to be fake, attracted criticism and concern.[140][141]

Discontinuation of third-party fact-checkers

In January 2025, Meta ended its use of third-party fact-checkers in favor of a user-run community notes system similar to the one used on X.[142][143]

While Zuckerberg supported these changes, saying that the amount of censorship on the platform was excessive, the decision received criticism by fact-checking institutions, stating that the changes would make it more difficult for users to identify misinformation.[144] Meta also faced criticism for weakening its policies on hate speech that were designed to protect minorities and LGBTQ+ individuals from bullying and discrimination.[145][146][147] While moving its content review teams from California to Texas, Meta changed their hateful conduct policy to eliminate restrictions on anti-LGBT and anti-immigrant hate speech, as well as explicitly allowing users to accuse LGBT people of being mentally ill or abnormal based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.[148][149][150][151]

Lawsuits

Numerous lawsuits have been filed against the company, both when it was known as Facebook, Inc., and as Meta Platforms.

In March 2020, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) sued Facebook, for significant and persistent infringements of the rule on privacy involving the Cambridge Analytica fiasco. Every violation of the Privacy Act is subject to a theoretical cumulative liability of $1.7 million. The OAIC estimated that a total of 311,127 Australians had been exposed.[152]

On December 8, 2020, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and 46 states (excluding Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and South Dakota), the District of Columbia and the territory of Guam, launched Federal Trade Commission v. Facebook as an antitrust lawsuit against Facebook. The lawsuit concerns Facebook's acquisition of two competitors—Instagram and WhatsApp—and the ensuing monopolistic situation. FTC alleges that Facebook holds monopolistic power in the U.S. social networking market and seeks to force the company to divest from Instagram and WhatsApp to break up the conglomerate.[153] William Kovacic, a former chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, argued the case will be difficult to win as it would require the government to create a counterfactual argument of an internet where the Facebook-WhatsApp-Instagram entity did not exist, and prove that harmed competition or consumers.[154]

On December 24, 2021, a court in Russia fined Meta for $27 million after the company declined to remove unspecified banned content. The fine was reportedly tied to the company's annual revenue in the country.[155]

In May 2022, a lawsuit was filed in Kenya against Meta and its local outsourcing company Sama. Allegedly, Meta has poor working conditions in Kenya for workers moderating Facebook posts. According to the lawsuit, 260 screeners were declared redundant with confusing reasoning. The lawsuit seeks financial compensation and an order that outsourced moderators be given the same health benefits and pay scale as Meta employees.[156][157]

In June 2022, 8 lawsuits were filed across the U.S. over the allege that excessive exposure to platforms including Facebook and Instagram has led to attempted or actual suicides, eating disorders and sleeplessness, among other issues. The litigation follows a former Facebook employee's testimony in Congress that the company refused to take responsibility. The company noted that tools have been developed for parents to keep track of their children's activity on Instagram and set time limits, in addition to Meta's "Take a break" reminders. In addition, the company is providing resources specific to eating disorders as well as developing AI to prevent children under the age of 13 signing up for Facebook or Instagram.[158]

In June 2022, Meta settled a lawsuit with the US Department of Justice. The lawsuit, which was filed in 2019, alleged that the company enabled housing discrimination through targeted advertising, as it allowed homeowners and landlords to run housing ads excluding people based on sex, race, religion, and other characteristics. The U.S. Department of Justice stated that this was in violation of the Fair Housing Act. Meta was handed a penalty of $115,054 and given until December 31, 2022, to shadow the algorithm tool.[159][160][161]

In January 2023, Meta was fined €390 million for violations of the European Union General Data Protection Regulation.[162]

In May 2023, the European Data Protection Board fined Meta a record €1.2 billion for breaching European Union data privacy laws by transferring personal data of Facebook users to servers in the U.S.[163]

In July 2024, Meta agreed to pay the state of Texas $1.4 billion to settle a lawsuit brought by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton accusing the company of collecting users' biometric data without consent, setting a record for the largest privacy-related settlement ever obtained by a state attorney general.[164]

In October 2024, Meta Platforms faced lawsuits in Japan from 30 plaintiffs who claimed they were defrauded by fake investment ads on Facebook and Instagram, featuring false celebrity endorsements. The plaintiffs are seeking approximately 2.8 million dollars in damages.[165]

Structure

Management

Meta's key management consists of:[166][167]

- Mark Zuckerberg, chairman and chief executive officer

- Javier Olivan, chief operating officer

- Sir Nick Clegg, president, global affairs

- Susan Li, chief financial officer

- Andrew Bosworth, chief technology officer

- David Wehner, chief strategy officer

- Chris Cox, chief product officer

- Jennifer Newstead, chief legal officer

As of October 2022[update], Meta had 83,553 employees worldwide.

Board of directors

As of June 2024[update], Meta's board consisted of the following directors;[168]

- Mark Zuckerberg (chairman, co-founder, controlling shareholder, and chief executive officer)

- Peggy Alford (non-executive director, executive vice president, global sales, PayPal)

- Marc Andreessen (non-executive director, co-founder and general partner, Andreessen Horowitz)

- Drew Houston (non-executive director, chairman and chief executive officer, Dropbox)

- Nancy Killefer (non-executive director, senior partner, McKinsey & Company)

- Robert M. Kimmitt (non-executive director, senior international counsel, WilmerHale)

- Tracey Travis (non-executive director, executive vice president, chief financial officer, Estée Lauder Companies)

- Tony Xu (non-executive director, chairman and chief executive officer, DoorDash)

- Hock Tan (CEO of Broadcom) [169]

- John D. Arnold (former Enron executive) [169]

- Dana White (non-executive director, president and CEO of UFC)[170]

- John Elkann (Stellantis chairman, and Exor CEO)[171]

- Charlie Songhurst[172]

Company governance

Roger McNamee, an early Facebook investor and Zuckerberg's former mentor, said Facebook had "the most centralized decision-making structure I have ever encountered in a large company".[173]

Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes has stated that chief executive officer Mark Zuckerberg has too much power, that the company is now a monopoly, and that, as a result, it should be split into multiple smaller companies. In an op-ed in The New York Times, Hughes said he was concerned that Zuckerberg had surrounded himself with a team that did not challenge him, and that it is the U.S. government's job to hold him accountable and curb his "unchecked power".[174] He also said that "Mark's power is unprecedented and un-American."[175] Several U.S. politicians agreed with Hughes.[176] European Union Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager stated that splitting Facebook should be done only as "a remedy of the very last resort", and that it would not solve Facebook's underlying problems.[177]

Revenue

| Year | Revenue $ | Growth % |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | $0.4[178] | — |

| 2005 | 9[178] | 2150 |

| 2006 | 48[178] | 433 |

| 2007 | 153[178] | 219 |

| 2008 | 280[179] | 83 |

| 2009 | 775[180] | 177 |

| 2010 | 2,000[181] | 158 |

| 2011 | 3,711[182] | 86 |

| 2012 | 5,089[183] | 37 |

| 2013 | 7,872[183] | 55 |

| 2014 | 12,466[184] | 58 |

| 2015 | 17,928[185] | 44 |

| 2016 | 27,638[186] | 54 |

| 2017 | 40,653[187] | 47 |

| 2018 | 55,838[188] | 37 |

| 2019 | 70,697[188] | 27 |

| 2020 | 85,965[189] | 22 |

| 2021 | 117,929[190] | 37 |

| 2022 | 116,609[191] | -1 |

| 2023 | 134,902[7] | 16 |

Facebook ranked No. 34 in the 2020 Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by revenue, with almost $86 billion in revenue[192] most of it coming from advertising.[193][194] One analysis of 2017 data determined that the company earned US$20.21 per user from advertising.[195]

According to New York, since its rebranding, Meta has reportedly lost $500 billion as a result of new privacy measures put in place by companies such as Apple and Google which prevents Meta from gathering users' data.[196][197]

Number of advertisers

In February 2015, Facebook announced it had reached two million active advertisers, with most of the gain coming from small businesses. An active advertiser was defined as an entity that had advertised on the Facebook platform in the last 28 days.[198] In March 2016, Facebook announced it had reached three million active advertisers with more than 70% from outside the United States.[199] Prices for advertising follow a variable pricing model based on auctioning ad placements, and potential engagement levels of the advertisement itself. Similar to other online advertising platforms like Google and Twitter, targeting of advertisements is one of the chief merits of digital advertising compared to traditional media. Marketing on Meta is employed through two methods based on the viewing habits, likes and shares, and purchasing data of the audience, namely targeted audiences and "look alike" audiences.[200]

Tax affairs

The U.S. IRS challenged the valuation Facebook used when it transferred IP from the U.S. to Facebook Ireland (now Meta Platforms Ireland) in 2010 (which Facebook Ireland then revalued higher before charging out), as it was building its double Irish tax structure.[201][202] The case is ongoing and Meta faces a potential fine of $3–5bn.[203]

The U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 changed Facebook's global tax calculations. Meta Platforms Ireland is subject to the U.S. GILTI tax of 10.5% on global intangible profits (i.e. Irish profits). On the basis that Meta Platforms Ireland Limited is paying some tax, the effective minimum US tax for Facebook Ireland will be circa 11%. In contrast, Meta Platforms Inc. would incur a special IP tax rate of 13.125% (the FDII rate) if its Irish business relocated to the U.S. Tax relief in the U.S. (21% vs. Irish at the GILTI rate) and accelerated capital expensing, would make this effective U.S. rate around 12%.[204][205][206]

The insignificance of the U.S./Irish tax difference was demonstrated when Facebook moved 1.5bn non-EU accounts to the U.S. to limit exposure to GDPR.[207][208]

Facilities

Offices

Users outside of the U.S. and Canada contract with Meta's Irish subsidiary, Meta Platforms Ireland Limited (formerly Facebook Ireland Limited), allowing Meta to avoid US taxes for all users in Europe, Asia, Australia, Africa and South America. Meta is making use of the Double Irish arrangement which allows it to pay 2–3% corporation tax on all international revenue.[209] In 2010, Facebook opened its fourth office, in Hyderabad, India,[210] which houses online advertising and developer support teams and provides support to users and advertisers.[211] In India, Meta is registered as Facebook India Online Services Pvt Ltd.[212] It also has support centers in Chittagong; Dublin;[clarification needed] California; Ireland; and Austin, Texas.[213][not specific enough to verify]

Facebook opened its London headquarters in 2017 in Fitzrovia in central London. Facebook opened an office in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 2018. The offices were initially home to the "Connectivity Lab", a group focused on bringing Internet access to those who do not have access to the Internet.[214] In April 2019, Facebook opened its Taiwan headquarters in Taipei.[215]

In March 2022, Meta opened new regional headquarters in Dubai.[216]

In September 2023, it was reported that Meta had paid £149m to British Land to break the lease on Triton Square London office. Meta reportedly had another 18 years left on its lease on the site.[217]

-

Entrance to Meta's headquarters complex in Menlo Park, California

-

Facebook headquarters in 2014

Data centers

As of 2023, Facebook operated 21 data centers.[218] It committed to purchase 100% renewable energy and to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 75% by 2020.[219] Its data center technologies include Fabric Aggregator, a distributed network system that accommodates larger regions and varied traffic patterns.[220]

Reception

US Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez responded in a tweet to Zuckerberg's announcement about Meta, saying: "Meta as in 'we are a cancer to democracy metastasizing into a global surveillance and propaganda machine for boosting authoritarian regimes and destroying civil society ... for profit!'"[221]

Ex-Facebook employee Frances Haugen and whistleblower behind the Facebook Papers responded to the rebranding efforts by expressing doubts about the company's ability to improve while led by Mark Zuckerberg, and urged the chief executive officer to resign.[222]

In November 2021, a video published by Inspired by Iceland went viral, in which a Zuckerberg look-alike promoted the Icelandverse, a place of "enhanced actual reality without silly looking headsets".[223]

In a December 2021 interview, SpaceX and Tesla chief executive officer Elon Musk said he could not see a compelling use-case for the VR-driven metaverse, adding: "I don't see someone strapping a frigging screen to their face all day."[224]

In January 2022, Louise Eccles of The Sunday Times logged into the metaverse with the intention of making a video guide. She wrote:

Initially, my experience with the Oculus went well. I attended work meetings as an avatar and tried an exercise class set in the streets of Paris. The headset enabled me to feel the thrill of carving down mountains on a snowboard and the adrenaline rush of climbing a mountain without ropes. Yet switching to the social apps, where you mingle with strangers also using VR headsets, it was at times predatory and vile.

Eccles described being sexually harassed by another user, as well as "accents from all over the world, American, Indian, English, Australian, using racist, sexist, homophobic and transphobic language". She also encountered users as young as 7 years old on the platform, despite Oculus headsets being intended for users over 13.[225]

See also

- Big Tech

- Criticism of Facebook

- Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal

- 2021 Facebook leak

- Meta AI

- The Social Network

Notes

- ^ As of 2023.

References

- ^ "Inline XBRL Viewer". Archived from the original on February 6, 2024. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ "Chris Cox is returning to Facebook as chief product officer". The Verge. June 11, 2020. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Facebook is getting more serious about becoming your go-to for mobile payments". The Verge. August 11, 2020. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ "Company Info". Facebook. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Shaban, Hamza (January 20, 2019). "Digital advertising to surpass print and TV for the first time, report says". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook – Financials". investor.fb.com. Archived from the original on December 14, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Meta Platforms, Inc. 2023 Annual Report (Form 10-K)". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. February 2, 2024. Archived from the original on February 3, 2024. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Saul, Derek (February 1, 2024). "Meta Earnings: Zuckerberg's 'Year Of Efficiency' Nets Greatest Profits Ever". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 5, 2024. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ Meta Platforms, Inc. (October 28, 2021). "Current Report (8-K)". Securities and Exchange Commission. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Rana, S. S.; Kalra, Co-Arpit; Sinha, Shilpi (March 17, 2022). "Facebook - Brand Rights Protection". Lexology. Archived from the original on July 14, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "Facebook Inc. Certificate of Incorporation" (PDF). September 1, 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

File Number 3835815

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis C. (January 31, 2012). "Facebook's Very First SEC Filing". The Atlantic. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Second Quarter 2021 Results". investor.fb.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Meta Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2023 Results; Initiates Quarterly Dividend". Facebook Investor Relations. February 1, 2024. Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Heath, Alex (October 19, 2021). "Facebook is planning to rebrand the company with a new name". Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Facebook Company is Now Meta". October 28, 2021. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Dwoskin, Elizabeth (October 28, 2021). "Facebook is changing its name to Meta as it focuses on the virtual world". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook announces name change to Meta in rebranding effort". The Guardian. October 28, 2021. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ "The Global 2000 2023". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 29, 2024. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ Irwin-Hunt, Alex (June 19, 2023). "Top 100 global innovation leaders". fDi Intelligence. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "Facebook Invests $5.7 Billion in Indian Internet Giant Jio". The New York Times. April 22, 2020. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ a b Heath, Alex (March 1, 2023). "This is Meta's AR / VR hardware roadmap for the next four years". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ "Form S-1 Registration Statement Under The Securities Act of 1933". January 1, 2012. Archived from the original on June 12, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ Erickson, Christine (January 3, 2012). "Facebook IPO: The Complete Guide". Mashable business. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- ^ Helft, Miguel; Hempel, Jessi (March 19, 2012). "Inside Facebook". Fortune. 165 (4): 122. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ^ Tangel, Andrew; Hamilton, Walter (May 17, 2012). "Stakes are high on Facebook's first day of trading". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ "Facebook boosts number of shares on offer by 25%". BBC News. May 16, 2012. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ a b Rusli, Evelyn M.; Eavis, Peter (May 17, 2012). "Facebook Raises $16 Billion in I.P.O." The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ Condon, Bernard (May 17, 2012). "Questions and answers on blockbuster Facebook IPO". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Retrieved May 17, 2012. [permanent dead link] Alternate Link Archived

- ^ Gross, Doug (March 17, 2012). "Internet greets Facebook's IPO price with glee, skepticism". CNN. Archived from the original on May 17, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ Straburg, Jenny; Bunge, Jacob (May 18, 2012). "Trading Problems Persisted After Opening for Facebook's IPO". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 14, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ Bunge, Jacob; Strasburg, Jenny; Dezember, Ryan (May 18, 2012). "Facebook Falls Back to IPO Price". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ Michael J. De La Mercred (May 18, 2012). "Facebook Closes at $38.23, Nearly Flat on Day". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ O'Dell, Jolie (May 18, 2012). "Facebook disappoints on its opening day, closing down $4 from where it opened". Venture Beat. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ "Facebook Sets Record For IPO Trading Volume". The Wall Street Journal. May 18, 2012. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ Womack, Brian; Thomson, Amy (May 21, 2012). "Facebook falls below $38 IPO price in second day of trading". The Washington Post. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Evelyn M. Rusli and Michael J. De La Merced (May 22, 2012). "Facebook I.P.O. Raises Regulatory Concerns". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ Temple, James; Newton, Casey (May 23, 2012). "Litigation over Facebook IPO just starting". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ Eichler, Alexander (May 24, 2012). "Wall St. Cashes In On Facebook Stock Plunge While Ordinary Investors Lose Millions". HuffPost. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Facebook to join S&P 500". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. December 11, 2013. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ Baer, Drake. "Mark Zuckerberg Explains Why Facebook Doesn't 'Move Fast And Break Things' Anymore". Business Insider. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook can't move fast to fix the things it broke". Engadget. April 12, 2018. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Blodget, Henry (October 1, 2009). "Mark Zuckerberg On Innovation". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook Goes After TikTok With the Debut of Lasso". Fortune. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ "Facebook is shutting down Lasso, its TikTok clone". TechCrunch. July 2, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Leskin, Paige. "Facebook is dumping its failed TikTok clone Lasso to make way for its other TikTok clone on Instagram". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 22, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Salvador Rodriguez (October 30, 2021). "Facebook's Meta mission was laid out in a 2018 paper on The Metaverse". CNBC. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ "Bitcoin Above $8,000; Facebook Opens Crypto Company in Switzerland". Investing.com. May 20, 2019. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Reiff, Nathan. "Facebook Gathers Companies to Back Cryptocurrency Launch". Investopedia. Archived from the original on June 18, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Murphy, Hannah (November 27, 2020). "Facebook's Libra currency to launch next year in limited format". Financial Times. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook Libra: the inside story of how the company's cryptocurrency dream died". Financial Times. March 10, 2022. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ "Facebook-funded cryptocurrency Diem winds down". BBC News. February 1, 2022. Archived from the original on February 15, 2022. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Thorbecke, Catherine (November 10, 2022). "Silicon Valley's greatest minds misread pandemic demand. Now their employees are paying for it". CNN. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2022. Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Facebook's reported name change reinforces its image as the new Big Tobacco". Fast Company. October 21, 2021. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "FB Q3 2021 Earnings Call Transcript" (PDF). Facebook, Inc. October 25, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg on why Facebook is rebranding to Meta". October 28, 2021. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "Trademark Status & Document Retrieval (serial no. 86852664)". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Constine, Josh (January 23, 2017). "Chan Zuckerberg Initiative acquires and will free up science search engine Meta". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Gonzalez, Oscar (October 28, 2021). "Chan Zuckerberg Initiative to sunset its Meta project". CNET. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Seetharaman, Deepa; Rodriguez, Salvador (February 2, 2022). "Facebook's Shares Plunge After Profit Decline". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 2, 2022. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c Wagner, Kurt (February 2, 2022). "Meta Faces Historic Stock Rout After Facebook Growth Stalled". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on February 2, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Bobrowsky, Meghan (February 3, 2022). "Facebook Feels $10 Billion Sting From Apple's Privacy Push". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Nix, Naomi (February 3, 2022). "Zuckerberg Tells Staff to Focus on Video Products as Meta's Stock Plunges". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Carpenter, Scott (February 2, 2022). "Zuckerberg's Wealth Plunges by $31 Billion After Meta Shock". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "Bloomberg Billionaires Index: Mark Zuckerberg". Bloomberg. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Delouya, Samantha. "Here's why Mark Zuckerberg can't be fired as CEO of Meta". Archived from the original on May 9, 2023. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ Turton, William (March 30, 2022). "Apple and Meta Gave User Data to Hackers Who Used Forged Legal Requests". Yahoo! Finance. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Lawler, Richard; Heath, Alex (June 1, 2022). "Meta COO Sheryl Sandberg is stepping down after 14 years". The Verge. Archived from the original on June 16, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "Russia confirms Meta's designation as extremist". BBC News. October 11, 2022. Archived from the original on May 22, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Why Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses haven't caught on a year after launch". Quartz. September 12, 2022. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ "Ray-Ban Stories Now Globally Available with Meta | EssilorLuxottica". Essilor. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ "Facebook owner Meta in first ever sales fall for". BBC News. July 27, 2022. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Vanian, Jonathan (July 27, 2022). "Meta reports earnings, revenue miss and forecasts second straight quarter of declining sales". CNBC. Archived from the original on July 29, 2022. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ Heath, Alex (July 27, 2022). "Facebook reports drop in revenue for the first time". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 29, 2022. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ Mathews, Eva (July 28, 2022). "Meta to keep facing Apple privacy pinch, TikTok heat for now". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 29, 2022. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ Levy, Ari (October 27, 2022). "Facebook used to be a Big Tech giant — now Meta isn't even in the top 20 most valuable U.S. companies". CNBC. Archived from the original on October 28, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Vanian, Jonathan (November 9, 2022). "Meta laying off more than 11,000 employees: Read Zuckerberg's letter announcing the cuts". CNBC. Archived from the original on November 10, 2022. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ Goswami, Rohan; Vanian, Jonathan (April 19, 2023). "Meta has started its latest round of layoffs, focusing on technical employees". CNBC. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ "From Twitter to Meta: Tech Layoffs by the Numbers". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Paul, Kari (April 19, 2023). "Thousands of Meta workers hit by new round of layoffs as company cuts costs". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Paul, Katie; Hu, Krystal; Nellis, Stephen; Tong, Anna (April 25, 2023). "Insight: Inside Meta's scramble to catch up on AI". Reuters.

- ^ Zhang, Angela Huyue (2024). High Wire: How China Regulates Big Tech and Governs Its Economy. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197682258.001.0001. ISBN 9780197682258.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (March 14, 2023). "Facebook owner Meta announces further 10,000 job losses". Eurogamer.net. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ Paul, Kari (April 26, 2023). "Meta reports surprisingly strong quarter one earnings after restructuring hiccups". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ Isaac, Mike (July 4, 2023). "Meta's 'Twitter Killer' App Is Coming". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ "Meta Opens AI Chatbot Tech for Commercial Use via Microsoft". Yahoo! Finance. July 18, 2023. Archived from the original on July 18, 2023. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ Dotan, Tom; Seetharaman, Deepa (July 18, 2023). "Meta, Microsoft Team Up to Offer New AI Software for Businesses". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on July 18, 2023. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ "All news in Canada will be removed from Facebook, Instagram within weeks: Meta". ctvnews. The Canadian Press. August 2023. Archived from the original on August 1, 2023. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ Vanian, Jonathan (January 18, 2024). "Mark Zuckerberg indicates Meta is spending billions of dollars on Nvidia AI chips". CNBC. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Prescott, Katie (January 9, 2024). "Mark Zuckerberg in $185m sale as Meta rebounds". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on January 9, 2024. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Saul, Derek. "Meta Stock Sets Record High—How It Emerged From 77% Plunge And Metaverse Fiasco". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 29, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "EU privacy watchdogs urged to oppose Meta's paid ad-free service". The Economic Times. February 16, 2024. Archived from the original on February 16, 2024. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ "Meta removes Facebook and Instagram accounts of Iran's Supreme Leader". CNN. February 9, 2024. Archived from the original on February 11, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ Nerozzi, Timothy (March 16, 2024). "Social media giant Meta under investigation for alleged drug sales on its platforms: WSJ". FOXBusiness. Archived from the original on March 17, 2024. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ "EU investigates Facebook and Instagram over child safety". BBC. May 16, 2024. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Rankin, Jennifer (May 16, 2024). "EU investigates Facebook owner Meta over child safety and mental health concerns". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 10, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ "Facebook and Instagram face fresh scrutiny under the European Union's strict digital regulations". AP News. May 16, 2024. Archived from the original on June 10, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ "EU investigating Meta over addiction and safety concerns for minors". Yahoo! Finance. May 16, 2024.

- ^ "Scammers Target Middle East Influencers With Meta's Own Tools". Bloomberg. July 29, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ "Meta bans Russian state media outlets for social media 'interference' campaigns". September 17, 2024. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ Vanian, Jonathan (September 27, 2024). "Hands-on with Meta's Orion AR glasses prototype and the possible future of computing". CNBC. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

- ^ Heath, Alex (September 25, 2024). "Hands-on with Orion, Meta's first pair of AR glasses". The Verge. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

They're called Orion, and they're Meta's first pair of augmented reality glasses. The company was supposed to sell them but decided not to because they are too complicated and expensive to manufacture right now.

- ^ Roettgers, Janko (September 27, 2024). "Meta's Orion glasses show that consumer AR wearables are almost here". Fast Company. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

At this point, Orion would be much too expensive, and too hard to manufacture, to achieve mass-market scale. The company only produced a small number of Orion glasses that will primarily be given out to company executives and employees.

- ^ Paul, Katie (October 6, 2024). "Meta, challenging OpenAI, announces new AI model that can generate video with sound". Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ Silverman, Craig; Bengani, Priyanjana (October 31, 2024). "Exploiting Meta's Weaknesses, Deceptive Political Ads Thrived on Facebook and Instagram in Run-Up to Election". ProPublica. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ Sheidlower, Noah. "Meta is reportedly building a $10 billion underwater cable that will circle the globe". Business Insider. Retrieved December 2, 2024.

- ^ Arntz, Pieter (November 2, 2024). "Meta takes down more than 2 million accounts in fight against pig butchering". Malwarebytes. Retrieved December 3, 2024.

- ^ Taylor, Josh (December 1, 2024). "Meta to force financial advertisers to be verified in bid to prevent celebrity scam ads targeting Australians". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved December 2, 2024.

- ^ Brook, Jack; Sainz, Adrian (December 5, 2024). "Meta to build $10 billion AI data center in Louisiana as Elon Musk expands his Tennessee AI facility". Tech Xplore. Archived from the original on December 17, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Peters, Jay (December 11, 2024). "Facebook, Instagram, and Threads are down". The Verge. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Helft, Miguel (May 17, 2011). "For Buyers of Web Start-Ups, Quest to Corral Young Talent". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook buys Instagram for $1 billion". weebly. Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ Lunden, Ingrid (October 13, 2013). "Facebook Buys Mobile Data Analytics Company Onavo, Reportedly For Up To $200M… And (Finally?) Gets Its Office In Israel". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Rosen, Guy (November 7, 2013). "We are joining the Facebook team". Onavo Blog. Archived from the original on November 7, 2013. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Covert, Adrian (January 19, 2014). "Facebook buys WhatsApp for $19 billion". CNNMoney. CNN. Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ Stone, Brad (February 20, 2014). "Facebook Buys WhatsApp for $19 Billion". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (March 25, 2014). "Facebook Buys Oculus Rift For $2 Billion". Kotaku.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Marshall, Cass (November 26, 2019). "Facebook acquires Beat Saber developer". Polygon. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Abram. "Facebook Buys Giphy For $400 Million". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ Aripaka, Pushkala (August 12, 2021). "Facebook may have to sell Giphy on Britain's competition concerns". Reuters. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Lomas, Natasha (October 20, 2021). "Facebook fined $70M for flouting Giphy order made by UK watchdog". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook owner Meta to sell Giphy after UK watchdog confirms ruling". The Guardian. October 18, 2022. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ Grantham-Philips, Wyatte (May 23, 2023). "Meta sells Giphy for $53M to Shutterstock after UK blocked GIF platform purchase". Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 24, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ Cimilluca, Cara Lombardo and Dana (November 30, 2020). "WSJ News Exclusive | Facebook to Buy customer, Startup Valued at $1 Billion". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ "Meta closes Kustomer deal after regulatory approval". Reuters. February 15, 2022. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ Salvador Rodriguez (September 2, 2022). "Meta Acquires Berlin Startup to Boost Virtual-Reality Ambitions". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 7, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ "Client Profile: Facebook Inc". OpenSecrets. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021.

- ^ Lauren Feiner, Facebook spent more on lobbying than any other Big Tech company in 2020. Archived February 18, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. CNBC.com. January 22, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook's lobbying spending surged to a record in 2021". Politico, January 21, 2022. January 21, 2022. Archived from the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg's Meta donates $1m to Trump fund". BBC News. December 12, 2024. Retrieved December 12, 2024.

- ^ Mark Zuckerberg has some regrets about how Meta handled COVID misinformation Rocio Fabbro, Quartz, Aug 27, 2024

- ^ Biddle, Sam (October 21, 2024). "Meta's Israel Policy Chief Tried to Suppress Pro-Palestinian Instagram Posts". The Intercept. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ Dedezade, Esat. "Meta Faces Backlash As Democrat-Related Terms Disappear From Instagram". Forbes.

- ^ Haysom, Sam (January 21, 2025). "Is Instagram blocking the #Democrat hashtag?". Mashable. Ziff Davis. Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- ^ Gerken, Tom. "Instagram hides search results for 'Democrats'". BBC. Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- ^ Shahani, Aarti (November 17, 2016). "From Hate Speech To Fake News: The Content Crisis Facing Mark Zuckerberg". NPR. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ Burke, Samuel (November 19, 2016). "Zuckerberg: Facebook will develop tools to fight fake news". CNN Money. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- ^ Jamieson, Amber; Solon, Olivia (December 15, 2016). "Facebook to begin flagging fake news in response to mounting criticism". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ Levin, Sam (May 16, 2017). "Facebook promised to tackle fake news. But the evidence shows it's not working". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ "Meta Oversight Board Warns of 'Incoherent' Rules After Fake Biden Video". TIME. February 5, 2024. Archived from the original on February 8, 2024. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Nix, Naomi (February 4, 2024). "Oversight Board rebukes Meta's policies after altered Biden video spreads". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "Meta is ending its fact-checking program in favor of a 'community notes' system similar to X's". NBC News. January 7, 2025. Retrieved January 16, 2025.

- ^ Isaac, Mike; Schleifer, Theodore (January 7, 2025). "Meta Says It Will End Its Fact-Checking Program on Social Media Posts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 16, 2025.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg says ending fact-checks will curb censorship. Fact-checkers say he's wrong. - CBS News". www.cbsnews.com. January 8, 2025. Retrieved January 16, 2025.

- ^ "NEW: GLAAD RESPONDS TO META'S LATEST ANTI-LGBTQ CHANGES TO CONTENT POLICY AND DEI THAT WILL HARM USERS". GLAAD. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ Factora, James. ""Trans People Are Freaks." Meta Leaks Reveal Specific Anti-LGBTQ+ Content the Company Now Allows". Them. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ Koebler, Jason. "Meta Deletes Trans and Nonbinary Messenger Themes". 404 Media. Retrieved January 11, 2025.

- ^ Knibbs, Kate. "Meta Now Lets Users Say Gay and Trans People Have 'Mental Illness'". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved January 7, 2025.

- ^ Schleifer, Theodore; Isaac, Mike (January 7, 2025). "Meta to End Fact-Checking on Facebook, Instagram Ahead of Trump Term: Live Updates". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 7, 2025.

- ^ "Inside Meta's dehumanizing new speech policies for trans people". Platformer. January 10, 2025. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ Biddle, Sam (January 10, 2025). "Leaked Meta Rules: Users Are Free to Post "Mexican Immigrants Are Trash!" or "Trans People Are Immoral"". The Intercept. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ "Facebook suffers blow in Australia legal fight over Cambridge Analytica". The Guardian. September 14, 2020. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren; Rodriguez, Salvador (December 8, 2020). "FTC and states sue Facebook, could force it to divest Instagram and WhatsApp". CNBC. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Fung, Brian. "The legal battle to break up Facebook is underway. Now comes the hard part". CNN. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ Khurshudyan, Isabelle (December 24, 2021). "Russia fines Google $100 million, and Meta $27 million, over 'failure to remove banned content'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ^ "Meta sued in Kenya over claims of exploitation and poor working conditions". CNN. Reuters. May 10, 2022. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ "A watershed': Meta ordered to offer mental health care to moderators in Kenya". The Guardian. June 7, 2023. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "Meta Hit With 8 Suits Claiming Its Algorithms Hook Youth and Ruin Their Lives". Bloomberg. June 8, 2022. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ "Meta settles US lawsuit over housing discrimination". news.yahoo.com. June 21, 2022. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ "Meta settles lawsuit with Justice Department over ad-serving algorithms". TechCrunch. June 21, 2022. Archived from the original on June 22, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ "Meta Agrees to Alter Ad Technology in Settlement With U.S." The New York Times. June 21, 2022. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ Chan, Kelvin (January 4, 2023). "Meta fined $414m in latest European privacy crackdown". BostonGlobe.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ "Meta slapped with record $1.3 billion EU fine over data privacy". CNN. May 22, 2023. Archived from the original on May 22, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ Motley, Dante (July 30, 2024). "Meta to pay Texas $1.4 billion for using facial recognition technology without users' permission". The Texas Tribune. Archived from the original on August 15, 2024. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

- ^ "Meta faces lawsuits in Japan over fake Facebook, Instagram ads | NHK WORLD-JAPAN News". NHK WORLD. Retrieved November 6, 2024.

- ^ "Facebook Management". Facebook Investor Relations. Facebook. Archived from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ "Executives | Meta". about.meta.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2022. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ "Meta – Leadership & Governance". investor.fb.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ a b Vanian, Jonathan (February 14, 2024). "Meta says Broadcom CEO Hock Tan is joining board of directors". CNBC. Archived from the original on February 14, 2024. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ Newswire, PR. "Dana White, John Elkann and Charlie Songhurst to Join Meta Board of Directors". Yahoo Finance. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ "Meta - Leadership & Governance". investor.atmeta.com. Retrieved January 25, 2025.

- ^ "Dana White, John Elkann and Charlie Songhurst to Join Meta Board of Directors". Meta. January 6, 2025. Retrieved January 25, 2025.

- ^ Bissell, Tom (January 29, 2019). "An Anti-Facebook Manifesto, by an Early Facebook Investor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Brown, Shelby. "Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes calls for company's breakup". CNET. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Hughes, Chris (May 9, 2019). "Opinion | It's Time to Break Up Facebook". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Brown, Shelby. "More politicians side with Facebook co-founder on breaking up company". CNET. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Collins, Katie. "EU competition commissioner: Facebook breakup would be 'last resort'". CNET. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Tsotsis, Alexia (February 1, 2012). "Facebook's IPO: An End To All The Revenue Speculation". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Arrington, Michael (May 19, 2009). "Facebook Turns Down $8 billion Valuation Term Sheet, Claims 2009 Revenues Will Be $550 million". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on July 12, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ Tsotsis, Alexia (January 5, 2011). "Report: Facebook Revenue Was $777 Million In 2009, Net Income $200 Million". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ Womack, Brian (December 16, 2010). "Facebook 2010 Sales Said Likely to Reach $2 Billion, More Than Estimated". Bloomberg. New York. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2012 Results". Facebook. January 30, 2013. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2013 Results". Facebook. January 29, 2014. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2014 Results". Facebook. Archived from the original on January 29, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2015 Results". Facebook. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ "Facebook Annual Report 2016" (PDF). Facebook. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2017 Results". Facebook. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ a b "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2018 Results". investor.fb.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2020 Results". investor.fb.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "Meta Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2021 Results". Meta Platforms. February 3, 2022. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "Meta Platforms, Inc. 2022 Annual Report (Form 10-K)". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. February 2, 2023. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ "Facebook | 2021 Fortune 500". Fortune. Archived from the original on July 6, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Jolie O'Dell (January 17, 2011). "Facebook's Ad Revenue Hit $1.86B for 2010". Mashable. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Womack, Brian (September 20, 2011). "Facebook Revenue Will Reach $4.27 Billion, EMarketer Says". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on December 19, 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Malloy, Daniel (May 27, 2019). "Too Big NOT To Fail?". OZY. "What's your online data really worth? About $5 a month". Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Dugan, Kevin T. (February 18, 2022). "Zuckerberg Has Burned $500 Billion Turning Facebook to Meta". New York. Archived from the original on February 22, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Corrigan, Hope (February 22, 2022). "Facebook has lost $500 billion since rebranding to Meta". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on February 22, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Meola, Andrew (February 24, 2015). "Active, in this case, means the advertiser has advertised on the site in the last 28 days". TheStreet. TheStreet, Inc. Archived from the original on February 27, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ "3 Million Advertisers on Facebook". Facebook for Business. Archived from the original on June 18, 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Complete interview with Brad Parscale and the Trump marketing strategy". PBS Frontline.

- ^ "Facebook must give judge documents for U.S. tax probe of Irish unit". Reuters. March 28, 2018. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook's Dublin HQ central to $5bn US tax probe". Sunday Business Post. April 1, 2018. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook Ordered to Comply With U.S. Tax Probe of Irish Unit". Bloomberg. March 28, 2018. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "KPMG Report on TCJA" (PDF). KPMG. February 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Breaking Down the New U.S. Corporate Tax Law". Harvard Business Review. December 26, 2017. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "US corporations could be saying goodbye to Ireland". The Irish Times. January 17, 2018. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Exclusive: Facebook to put 1.5 billion users out of reach of new EU privacy law". Reuters. April 19, 2018. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook moves 1.5bn users out of reach of new European privacy law". The Guardian. London. April 19, 2018. Archived from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Drucker, Jesse (October 21, 2010). "Google 2.4% Rate Shows How $60 Billion Lost to Tax Loopholes". Bloomberg. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ PTI (September 30, 2010). "Facebook opens office in India". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Facebook's Hyderabad Office Inaugurated – Google vs Facebook Battle Comes To India". Watblog.com. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Not responsible for user-generated content hosted on website: Facebook India". Articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com. February 29, 2012. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Zuckerberg at Ore. Facebook data center". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. April 16, 2011. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Nanos, Janelle (August 30, 2017). "Facebook to open new office in Kendall Square, adding hundreds of jobs". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ "Facebook opens new Taiwan headquarters in Taipei". Taiwan Today. April 12, 2019. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ "Sheikh Hamdan opens Meta's new regional headquarters in Dubai". The National. March 8, 2022. Archived from the original on March 9, 2022. Retrieved March 9, 2022.