FAM86B1

| FAM86B1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | FAM86B1, family with sequence similarity 86 member B1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 616122; MGI: 1917761; GeneCards: FAM86B1; OMA:FAM86B1 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FAM86B1 is a protein, which in humans is encoded by the FAM86B1 gene. FAM86B1 is an essential gene in humans.[11] The protein contains two domains: FAM86, and AdoMet-MTase.

FAM86B1 homologs are found in most eukaryotes, from mammals to plants such as wild soybean.

Gene

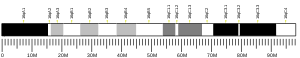

[edit]FAM86B1 in the human genome is located at 8p23.1, spanning about 12,000 base pairs. FAM86B1 contains 9 exons.[12]

8p23.1 is the location of one of the largest and most common genetic inversions in humans.[13] FAM86B1 is upregulated in inv-8p23.1.[14] In the non-inverted allele 8p23.1, FAM86B1 is on the negative strand.[15] In the allele inv-8p23.1, FAM86B1 is on the positive strand.[16]

Production

[edit]In humans, there are 20 alternative splicings of FAM86B1, and 19 mRNA transcripts. In humans, FAM86B1 is expressed ubiquitously,[17] and most strongly in brain tissues and the pituitary gland.[18]

Protein

[edit]The human FAM86B1 protein contains two domains, FAM86 and AdoMet-MTase, making FAM86B1 a member of these two protein families.[19] The human FAM86B1 gene encodes 13 protein isoforms. FAM86B1 is a non-classically secreted protein, targeted to the peroxisome by a C-terminus signal.[20]

FAM86B1 interacts with ubiquitin-C[21] and FAM86C1.[22]

Evolution

[edit]FAM86B1 homologs are seen in most eukaryotes, but are not found in distant plants, such as green algae. Wild soybean is the most distant species from humans with a FAM86B1 homolog.

FAM86B1 in humans is paralogous with other FAM86 protein-coding genes.

| Gene symbol | Gene location | NCBI gene ID |

|---|---|---|

| EEF2KMT | 16p13.3 | 196483 |

| FAM86B1 | 8p23.1 | 85002 |

| FAM86B2 | 8p23.1 | 653333 |

| FAM86B3 | 8p23.1 | 286042 |

| LOC128966622 | 8p23.1 | 128966622 |

| FAM86C1 | 11q13.4 | 55199 |

| FAM86C2 | 11q13.2 | 645332 |

Clinical significance

[edit]Cancer

[edit]Alternative splicings of FAM86B1 are associated with decreased relapse in rectal cancer[23] and surviving longer in glioblastoma.[24] In bladder urothelial carcinoma, a differing FAM86B1 expression pattern compared to noncancer controls is associated with surviving longer.[25] In glioma, lower survival rates are associated with downregulation of FAM86B1.[26] Loss of FAM86B1 expression is associated with uterine carcinosarcoma, prostate adenocarcinoma, and bladder urothelial carcinoma.[27]

Infection

[edit]Severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis is associated with downregulation of FAM86B1.[28] Enterovirus-71, a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus, binds to FAM86B1.[29] FAM86B1 is upregulated after exposure to the infection agent of Candida albicans.[30]

Inflammation

[edit]FAM86B1 is upregulated after exposure to oS100A4, a potential trigger of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis.[30] FAM86B1 is downregulated after remote ischemic preconditioning, which inhibits inflammation regulation.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000186523 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022544 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "AlphaFold Protein Structure Database". alphafold.ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, et al. (August 2021). "Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold". Nature. 596 (7873): 583–589. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..583J. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. PMC 8371605. PMID 34265844.

- ^ Varadi M, Anyango S, Deshpande M, Nair S, Natassia C, Yordanova G, et al. (January 2022). "AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models". Nucleic Acids Research. Volume 50, Issue D1. 50 (D1): D439 – D444. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab1061. PMC 8728224. PMID 34791371.

- ^ "iCn3D: Web-based 3D Structure Viewer". structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2023-12-15.

- ^ Wang J, Youkharibache P, Zhang D, Lanczycki CJ, Geer RC, Madej T, et al. (January 2020). "iCn3D, a web-based 3D viewer for sharing 1D/2D/3D representations of biomolecular structures". Bioinformatics. 36 (1): 131–135. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btz502. PMC 6956771. PMID 31218344.

- ^ Wang J, Youkharibache P, Marchler-Bauer A, Lanczycki C, Zhang D, Lu S, et al. (2022). "iCn3D: From Web-Based 3D Viewer to Structural Analysis Tool in Batch Mode". Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 9: 831740. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2022.831740. PMC 8892267. PMID 35252351.

- ^ Francis JW, Shao Z, Narkhede P, Trinh AT, Lu J, Song J, et al. (July 2023). "The FAM86 domain of FAM86A confers substrate specificity to promote EEF2-Lys525 methylation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 299 (7). Elsevier Inc on behalf of American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology: 104842. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2023.104842. PMC 10285254. PMID 37209825.

- ^ "FAM86B1 family with sequence similarity 86 member B1 [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ Salm MP, Horswell SD, Hutchison CE, Speedy HE, Yang X, Liang L, et al. (June 2012). "The origin, global distribution, and functional impact of the human 8p23 inversion polymorphism". Genome Research. 22 (6): 1144–1153. doi:10.1101/gr.126037.111. PMC 3371712. PMID 22399572.

- ^ Carreras-Gallo N, Cáceres A, Balagué-Dobón L, Ruiz-Arenas C, Andrusaityte S, Carracedo Á, et al. (May 2022). "The early-life exposome modulates the effect of polymorphic inversions on DNA methylation". Communications Biology. 5 (1): 455. doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03380-2. PMC 9098634. PMID 35550596.

- ^ "Homo sapiens genome assembly GRCh38.p14". NCBI. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ^ "Homo sapiens genome assembly T2T-CHM13v2.0". NCBI. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ^ "4702180 - GEO Profiles - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ "FAM86B1 transcriptomics data - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ "putative protein N-methyltransferase FAM86B1 [Homo sapiens] - Protein". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ^ "PSORT Users' Manual". psort.hgc.jp. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ Kim W, Bennett EJ, Huttlin EL, Guo A, Li J, Possemato A, et al. (October 2011). "Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome". Molecular Cell. 44 (2): 325–340. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.025. PMC 3200427. PMID 21906983.

- ^ Huttlin EL, Bruckner RJ, Navarrete-Perea J, Cannon JR, Baltier K, Gebreab F, et al. (May 2021). "Dual proteome-scale networks reveal cell-specific remodeling of the human interactome". Cell. 184 (11): 3022–3040.e28. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.011. PMC 8165030. PMID 33961781.

- ^ Zhang Z, Ji M, Lv Y, Feng Q, Zheng P, Mao Y, et al. (September 2020). "A signature predicting relapse based on integrated analysis on relapse-associated alternative mRNA splicing in I-III rectal cancer". Genomics. 112 (5): 3274–3283. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.06.021. PMID 32544549.

- ^ Zhao L, Zhang J, Liu Z, Wang Y, Xuan S, Zhao P (2021). "Comprehensive Characterization of Alternative mRNA Splicing Events in Glioblastoma: Implications for Prognosis, Molecular Subtypes, and Immune Microenvironment Remodeling". Frontiers in Oncology. 10: 555632. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.555632. PMC 7870873. PMID 33575206.

- ^ Yan J, Li P, Gao R, Li Y, Chen L (2021). "Identifying Critical States of Complex Diseases by Single-Sample Jensen-Shannon Divergence". Frontiers in Oncology. 11: 684781. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.684781. PMC 8212786. PMID 34150649.

- ^ Yang S, Zheng Y, Zhou L, Jin J, Deng Y, Yao J, et al. (December 2020). "miR-499 rs3746444 and miR-196a-2 rs11614913 Are Associated with the Risk of Glioma, but Not the Prognosis". Molecular Therapy. Nucleic Acids. 22: 340–351. doi:10.1016/j.omtn.2020.08.038. PMC 7527625. PMID 33230439.

- ^ Carlson SM, Gozani O (November 2016). "Nonhistone Lysine Methylation in the Regulation of Cancer Pathways". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 6 (11): a026435. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a026435. PMC 5088510. PMID 27580749.

- ^ Besteman SB, Callaghan A, Langedijk AC, Hennus MP, Meyaard L, Mokry M, et al. (November 2020). "Transcriptome of airway neutrophils reveals an interferon response in life-threatening respiratory syncytial virus infection". Clinical Immunology. 220: 108593. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108593. PMID 32920212.

- ^ Rattanakomol P (17 May 2021). Investigation of Role of Enterovirus A71 Nonstructural 3A Protein and Interacting Protein in Viral Replication (PDF) (Doctoral dissertation). Dissertation Advisor Jeeraphong Thanongsaksrikul. Dissertation Co-Advisors Wanpen Chaicumpa, Pornpimon Angkasekwinai, Pongsri Tongtawe, Potjanee Srimanote, Suganya Yongkiettrakul. Thammasat University.

- ^ a b Neidhart M, Pajak A, Laskari K, Riksen NP, Joosten LA, Netea MG, et al. (2019). "Oligomeric S100A4 Is Associated With Monocyte Innate Immune Memory and Bypass of Tolerance to Subsequent Stimulation With Lipopolysaccharides". Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 791. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00791. PMC 6476283. PMID 31037071.

- ^ Lou Z, Wu W, Chen R, Xia J, Shi H, Ge H, et al. (2021-01-15). "Microarray analysis reveals a potential role of lncRNA expression in remote ischemic preconditioning in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury". American Journal of Translational Research. 13 (1): 234–252. PMC 7847506. PMID 33527021.