Events in the Life of Harold Washington

| ||

|---|---|---|

Transit projects

Related

|

||

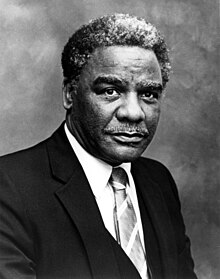

Events in the Life of Harold Washington is a mural at Chicago's central library, the Harold Washington Library, named after Harold Washington, Chicago's first Black mayor. The 10.5 foot high and 15.25 foot wide mural, painted on tiles by Jacob Lawrence, was commissioned in 1991. To evoke inspiration and empower progressive recollection, Lawrence's mural commemorates Washington's life and highlights the African diasporic population's victory against the white power structure of 20th century Chicago. It adds to the artist's lifelong examination of the meaning of Black progress and struggle.

Background

[edit]Twentieth Century Chicago, post-Great Migration, faced a racial divide that bore a white power structure. As an influx of Blacks increased the population of African diasporic people in Chicago from 109,000 in 1920 to 1.2 million in 1982, white Chicagoans reacted by moving out of their respective homes in the city, especially on the south side, towards the suburbs.[1] This was followed by forming a "Black metropolis" in which Blacks were confined to well-defined black areas and a physical line was drawn between races.[2] Blacks found themselves subjected to substandard housing, low-salary jobs, and no political representation.[1] White Chicagoans looked to Chicago's Democratic Party as a means to "at least conserve what they had for themselves while expecting improved schools, housing, and better jobs for their children…[seeing] the civil rights movement as a threat to these aspirations."[3] White Chicagoans knew that "corporate control of the economy [was] managed by and serve[d] the interest of a predominantly white ruling class" and maintained the status quo.[4] As stated by authors Abdul Alkalimat and Doug Gills, "racism operated in the [democratic] party to hold back Blacks from being incorporated equitably with anything approaching democratic representation."[5]

By preventing the Black vote in a physically divided city, led more Blacks to doubt their government and demand more political representation.[5] A struggle emerged from this turmoil in which "a Black political power evoke[d] fear in whites and a political response: the white power backlash."[6]

Up to 1982, Black Chicagoans faced a dilemma in which the "older and higher-income categories were overrepresented among black registrants…[and] voter-registration requirements had their greatest effect on poorly educated, low-income, and young voters".[7] The majority of Blacks in Chicago were not being represented in the voting process in a manner where their influence was felt, yet when factional struggles existed between the dominant political parties, Blacks would have had an opportunity to capitalize on this competition to satisfy their interests.[8] However, Paul Kleppner notes in his research that the "leaders of Chicago’s Machine factions were simply unwilling to risk white ethnic support by representing black racial interests."[8] Thus, when Washington stepped up to run for mayor, he faced low Black voter turnout, yet had the necessary characteristics to empower the Black community and "symbolize the mass response to growing systemic inequities" while dispelling a stigma of corrupt politics.[9]

Having grown up in politics as the son (and successor) of a precinct captain, Washington's familiarity with the politics of the Chicago Democratic Party allowed him to give it the most criticism.[10] His life accomplishments allowed him to transcend society's image of "Blackness", enabling him to appear as a serious and well-qualified candidate, as "scholar, athlete, Civilian Conservation Corps worker, soldier, lawyer, [or] U.S. Congressman."[11] With his "ability to engage in straight, no-nonsense dialogue with the ‘masses’ and the ‘elites’," Washington would gain deep support and appreciation from the Black community.[12] Exit polls showed Washington received overwhelming support among Blacks, affirming a movement for proper representation of them.[13] He represented a "symbol of black pride and progress," exposing the vulnerability of the institutionalized white power structure.[14]

Lawrence’s mural

[edit]Jacob Lawrence, in his Events in the Life of Harold Washington, painted in several vignettes and figures on ceramic tiles,[15] by incorporating themes of past works and his emotionally charged style; Lawrence has had a history of depicting historical occurrences to "examine the [African-Diasporic] struggle for justice, understanding, and a decent life," consistently bringing up a theme of progress and movement in Figure 1 of the mural.[16] This holds for his painting pictured in Figure 2, The March (1937), depicting the slave revolt of the Haitian Revolution. His featured 1984 ARTnews article states, "he charged that all history can be seen as a succession of mass movements, displacements and upheavals."[16] Figure 3 shows a panel from Lawrence's The Migration of the Negro where we can see the artist's distinguished art form. He uses bold, slashing brush strokes which give off the "pent-up energy, rage, and despair" seen in the painting.[16] According to ARTnews, it is Lawrence's "repeated jagged shapes; harsh, angular lines; a limited palette; and a slanting perspective that tip the scene toward the viewer."[17]

Events in the Life of Harold Washington does not stray away from these artistic characteristics. Lawerence uses a limited palette of blue, yellow, and green, and his figures come off as bold and jagged. The mural is set up in such a way as to create an apex where one's eyes gravitate toward the celebratory figure.[11]

In Events in the Life of Harold Washington Lawrence's motive was to re-create little-known historical images to inspire the audience to use their history to prove they were not inferior, but instead victors in past struggles.[16] Lawrence's mural and its themes of progress and movement honor the accomplishments of former Mayor Harold Washington and the symbolic representation of Black Chicago's triumph in the struggle for political power.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Abdul Alkalimat and Doug Gills, Harold Washington and the Crisis of Black Power in Chicago, (Chicago: Twentieth Century Books and Publications,1989), 113.

- ^ Paul Kleppner, Chicago Divided: The Making of a Black Mayor (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1985), 36.

- ^ Paul Kleppner, Chicago Divided: The Making of a Black Mayor (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1985), 9

- ^ Abdul Alkalimat and Doug Gills, Harold Washington and the Crisis of Black Power in Chicago, (Chicago: Twentieth Century Books and Publications, 1989), 109.

- ^ a b Paul Kleppner, Chicago Divided: The Making of a Black Mayor (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1985), 75-76.

- ^ Abdul Alkalimat and Doug Gills, Harold Washington and the Crisis of Black Power in Chicago, (Chicago: Twentieth Century Books and Publications, 1989), 111.

- ^ Paul Kleppner, Chicago Divided: The Making of a Black Mayor (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1985), 149.

- ^ a b Paul Kleppner, Chicago Divided: The Making of a Black Mayor (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1985), 133.

- ^ Abdul Alkalimat and Doug Gills, Harold Washington and the Crisis of Black Power in Chicago, (Chicago: Twentieth Century Books and Publications, 1989), 114.

- ^ James Haskins, "Harold Washington." In Distinguished African American Political and Governmental Leaders, Westport, CT: Oryx Press, 1999. The African American Experience. Greenwood Publishing Group. http://aae.greenwood.com.turing.library.northwestern.edu/doc. aspx?fileID=GR6126&chapterID=GR6126-2725&path=/books/greenwood//. (accessed November 14, 2009).

- ^ a b Richard J. Powell, Jacob Lawrence. (New York: Rizzoli, 1992), 4.

- ^ Abdul Alkalimat and Doug Gills, Harold Washington and the Crisis of Black Power in Chicago, (Chicago: Twentieth Century Books and Publications, 1989), 61.

- ^ Paul Kleppner, Chicago Divided: The Making of a Black Mayor (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1985), 166.

- ^ Paul Kleppner, Chicago Divided: The Making of a Black Mayor (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1985), 159.

- ^ Chicago government publication about art in the Harold Washington Library

- ^ a b c d Avis Berman, "Jacob Lawrence and the Making of Americans", ARTnews, February 1984, 80.

- ^ Avis Berman, "Jacob Lawrence and the Making of Americans", ARTnews, February 1984, 84.