European Green Deal

The European Green Deal, approved in 2020, is a set of policy initiatives by the European Commission with the overarching aim of making the European Union (EU) climate neutral in 2050.[1][2] The plan is to review each existing law on its climate merits, and also introduce new legislation on the circular economy (CE), building renovation, biodiversity, farming and innovation.[2]

The president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, stated that the European Green Deal would be Europe's "man on the moon moment".[2] On 13 December 2019, the European Council decided to press ahead with the plan, with an opt-out for Poland.[3] On 15 January 2020, the European Parliament voted to support the deal as well, with requests for higher ambition.[4] A year later, the European Climate Law was passed, which legislated that greenhouse gas emissions should be 55% lower in 2030 compared to 1990. The Fit for 55 package is a large set of proposed legislation detailing how the European Union plans to reach this target.[5]

The European Commission's climate change strategy, launched in 2020, is focused on a promise to make Europe a net-zero emitter of greenhouse gases by 2050 and to demonstrate that economies will develop without increasing resource usage. However, the Green Deal has measures to ensure that nations that are already reliant on fossil fuels are not left behind in the transition to renewable energy.[6][7][8] The green transition is a top priority for Europe. The EU Member States want to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels, and become climate neutral by 2050.[9][10][11][12]

Von der Leyen appointed Frans Timmermans as Executive Vice President of the European Commission for the European Green Deal in 2019. He was succeeded by Maroš Šefčovič in 2023.[13]

European Climate Pact

[edit]The European Climate Pact is an initiative of the European Commission supporting the implementation of the European Green Deal. It is a movement to build a greener Europe, providing a platform to work and learn together, develop solutions, and achieve real change.

The Pact provides opportunities for people, communities, and organizations to participate in climate and environmental action across Europe. By pledging to the Pact, European stakeholders commit to taking concrete climate and environmental actions in a way that can be measured and/or followed up. Participating in the Pact is an opportunity for organizations to share their transition journey with their peers and collaborate with other actors towards common targets.[14][15]

Aims

[edit]The overarching aim of the European Green Deal is for the European Union to become the world's first “climate-neutral bloc” by 2050. It has goals extending to many different sectors, including construction, biodiversity, energy, transport and food.[16]

The plan includes potential carbon tariffs for countries that don't curtail their greenhouse gas pollution at the same rate.[17] The mechanism to achieve this is called the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).[18] It also includes:

- a circular economy action plan,[19] The European Commission has released a number of publications on circular economy, including one that requires Member States to carry out activities related to changing their economies into circular economies. The CE has indeed become a key component of the European Green Deal and the Coronavirus Recovery Plan of the Von der Leyen Commission (2019–present), and it was a key component of the Juncker Commission's ambition to create a sustainable, low-carbon, resource-efficient, and competitive economy.[20]

- a review and possible revision (where needed) of the all relevant climate-related policy instruments, including the Emissions Trading System,

- a Farm to Fork strategy along with a focus shift from compliance to performance (which will reward farmers for managing and storing carbon in the soil, improved nutrient management, reducing emissions, ...),

- a revision of the Energy Taxation Directive which is looking closely at fossil fuel subsidies and tax exemptions (aviation, shipping),

- a sustainable and smart mobility strategy and

- an EU forest strategy. The latter will have as its key objectives effective afforestation, and forest preservation and restoration in Europe.

It also leans on Horizon Europe, to play a pivotal role in leveraging national public and private investments. Through partnerships with industry and member States, it will support research and innovation on transport technologies, including batteries, clean hydrogen, low-carbon steel making, circular bio-based sectors and the built environment.[21]

The EU plans to finance the policies set out in the Green Deal through an investment plan – InvestEU, which forecasts at least €1 trillion in investment. Furthermore, for the EU to reach its goals set out in the deal, it is estimated that approximately €260 billion a year is going to be required by 2030 in investments.[16]

Before 1970, almost half of all European residential structures were built. At the time, no consideration was given to the amount of energy used by materials and standards. At the present rate of refurbishment, reaching a highly energy-efficient and decarbonised building stock might take more than a century. One of the major aims of the European Green Deal is to “at least double or even triple” the current refurbishment rate of approximately 1%. This is also true outside of the EU. In addition to rehabilitation, investment is required to enable the development of new efficient and ecologically friendly structures.[22][23]

In July 2021, the European Commission released its “Fit for 55” legislation package, which contains important guidelines for the future of the automotive industry: All new cars sold in the EU must be zero-emission vehicles from 2035.[24]

In the context of the Paris Agreement, and therefore using today's emissions as baseline, since 1990 EU emissions already dropped by 25% at 2019,[25] a 55% reduction target using 1990 as baseline represents in 2019 terms a 40% reduction target, which can be calculated using this equation:

According to the Emissions Gap Report 2020 by the United Nations Environment Programme, meeting the Paris Agreement's 1.5 °C temperature increase target (with 66% probability) requires GtCO2e 34/59 = 57% emissions reduction globally from 2019 levels by 2030, therefore well above the 40% target of the European Green Deal.[26] This 57% emission reduction target at 2030 represents average global reductions, while advanced economies are expected to contribute more.[27]

Policy areas

[edit]Clean energy

[edit]Climate neutrality by the year of 2050 is the main goal of the European Green Deal.[28] For the EU to reach their target of climate neutrality, one goal is to decarbonise their energy system by aiming to achieve “net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.”[29] Their relevant energy directive is intended to be looked over and adjusted if problem areas arise. Many other in place and present regulations will also be reviewed.[29] In 2023, the Member states will update their climate and national energy plans to adhere to the EU's climate goal for 2030.[30] The key principles include:

- to “prioritise energy efficiency”

- to “develop a power sector based largely on renewable resources”,

- to secure an affordable EU energy supply

- and to have a “fully integrated, interconnected digitalised EU energy market.”[30]

In 2020, the European Commission unveiled its strategy for a greener, cleaner energy future. The EU Strategy for Energy System Integration serves as a framework for an energy transition, which comprises measures to achieve a more circular system, and measures to implement greater direct electrification as well as to develop clean fuels (including hydrogen[31]). The European Clean Hydrogen Alliance has also been launched as hydrogen has a special role to play in this seismic shift.[32][33]

By 2023, greentech was one of the few sectors in the EU where venture capital investments matched those in the United States, highlighting the impact of the EU's ambitious climate goals and government subsidies. The European Green Deal and accompanying government policies have driven substantial investment in greentech, particularly in areas like energy storage, circular economy initiatives, and agricultural technology. This focus has enabled the EU to close the existing investment gap with the US in these strategic sectors.[34]

Sustainable industry

[edit]Another target area to achieve the EU's climate goals is the introduction of the Circular Economy Industrial policy. In March 2020, the EU announced their Industrial Strategy with its aim to “empower citizens, revitalises regions and have the best technologies.”[35] Key points of this policy area include boosting the modern aspects of industries, influencing the exploration and creation of “climate neutral” circular economy friendly goods markets. This further entails the “decarbonisation and modernisation of energy-intensive industries such as steel and cement.”[36]

A ‘Sustainable products’ policy is also projected to be introduced which will focus on reducing the wastage of materials. This aims to ensure products will be reused and recycling processes will be reinforced.[29] The materials particularly focused on include “textiles, construction, vehicles, batteries, electronics and plastics.”[37] The European Union is also of the opinion that it "should stop exporting its waste outside of the EU" and it will therefore "revisit the rules on waste shipments and illegal exports"[38][39] The EU mentioned that "the Commission will also propose to revise the rules on end-of-life vehicles with a view to promoting more circular business models."[19] The European Commission estimates that up to 2030, Europe's green investment offensive will cost an additional €350 billion annually.[9][40][41]

Building and renovation

[edit]This policy area is targeting the process of building and renovation in regards to their currently unsustainable methods. Many non-renewable resources are used in the process as well. Thus, the plan focuses on promoting the use of energy efficient building methods such as climate proofing buildings, increasing digitalisation and enforcing rules surrounding the energy performance of buildings. Social housing renovation will also occur in order to reduce the price of energy bills for those less able to finance these costs.[42] They aim to triple the renovation rate of all buildings to reduce the pollution emitted during these processes.[29]

Digital technologies are important in achieving the European Green Deal's environmental targets. Emerging digital technologies, if correctly applied, have the potential to play a critical role in addressing environmental issues. Smart city mobility, precision agriculture, sustainable supply chains, environmental monitoring, and catastrophe prediction are just a few examples.[43][44]

Farm to Fork

[edit]The ‘From Farm to Fork’ strategy pursues the issue of food sustainability as well as the support allocated to the producers, i.e. farmers and fishermen.[45] The methods of production and transfer of these resources are what the E.U. considers a climate-friendly approach, aiming to increase efficiency as well. The price and quality of the goods will aim to not be hindered during these newly adopted processes. Specific target areas include reducing the use of chemical pesticides, increasing the availability of health food options and aiding consumers to understand the health ratings of products and sustainable packaging.[46]

In the official page of the program From Farm to Fork is cited Frans Timmermans the Executive Vice-president of the European Commission, saying that:

"The coronavirus crisis has shown how vulnerable we all are, and how important it is to restore the balance between human activity and nature. At the heart of the Green Deal the Biodiversity and Farm to Fork strategies point to a new and better balance of nature, food systems and biodiversity; to protect our people’s health and well-being, and at the same time to increase the EU’s competitiveness and resilience. These strategies are a crucial part of the great transition we are embarking upon."[47]

The program includes the next targets:

- Making 25% of EU agriculture organic, by 2030.

- Reduce by 50% the use of pesticides by 2030.

- Reduce the use of Fertilizers by 20% by 2030.

- Reduce nutrient depletion by at least 50%.

- Reduce the use of antimicrobials in agriculture and antimicrobials in aquaculture by 50% by 2030.

- Create sustainable food labeling.

- Reduce food waste by 50% by 2030.

- Dedicate to R&I related to the issue €10 billion.[47]

Eliminating pollution

[edit]The ‘Zero Pollution Action Plan’ that aims to be adopted by the commission in 2021 intends to achieve no pollution from “all sources”, cleaning the air, water and soil by 2050.[48] The Environment Quality standards are to be fully met, enforcing all industrial activities to be within toxic-free environments. Agricultural and urban industries water management policies will be overlooked to suit the “no harm” policy.[48] Harmful resources such as micro-plastics and chemicals, such as pharmaceuticals, that are threatening the environment aim to be substituted in order to reach this goal.[37] The ‘Farm to Fork’ strategy aids pollution reduction from excess nutrients and sustainable methods of production and transportation.[49]

Some formulations of the plan such as "toxic-free" and "zero pollution" have been criticized by Genetic Literacy Project as anti-scientific and contradictory, as any substance can be toxic at specific dose, and almost any life-related process results in "pollution".[50]

Sustainable mobility

[edit]A reduction in emissions from transportation methods is another target area within the European Green Deal. A comprehensive strategy on "Sustainable and Smart mobility" intends to be implemented.[18] This will increase the adoption of sustainable and alternative fuels in road, maritime and air transport[51] and fix the emission standards for combustion-engine vehicles.[37] It also aims to make sustainable alternative solutions available to businesses and the public. Smart traffic management systems and applications intend to be developed as a solution. Freight delivery methods aim to be altered, with preferred pathways being by land or water.[52] Public transport alterations aim to reduce public congestion as well as pollution. Installations of charging ports for electric vehicles intends to encourage the purchase of low-emission vehicles.[52] The ‘Single European Sky’ plan focuses on air traffic management in order to increase safety, flight efficiency and environmentally friendly conditions.[53]

Biodiversity and ecosystem health

[edit]

A strategy surrounding the protection of the European Union's biodiversity will be put forth in 2021. Management of forests and maritime areas, environment protection and addressing the issue of losses of species and ecosystems are all aspects of this target area.[37]

Restoration of affected ecosystems is intended to occur through implementing organic farming methods, aiding pollination processes, restoring free flowing rivers, reducing pesticides that harm surrounding wildlife and reforestation.[54] The EU wants to protect 30% of land and 30% of sea, whilst creating stricter safeguards around new and old growth forests. Their aim is to restore ecosystems and their biological levels.[54]

The official page of the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 cites Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, saying that:

"Making nature healthy again is key to our physical and mental wellbeing and is an ally in the fight against climate change and disease outbreaks. It is at the heart of our growth strategy, the European Green Deal, and is part of a European recovery that gives more back to the planet than it takes away."[55]

The biodiversity strategy is an essential part of the climate change mitigation strategy of the European Union. From the 25% of the European budget that will go to fight climate change, a large portion of that will be dedicated to restoring biodiversity and nature based solutions.

The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 includes the following targets:

- Protect 30% of the sea territory and 30% of land territory especially primary forests and old-growth forests.

- Plant 3 billion trees by 2030.

- Restore at least 25,000 kilometers of rivers, so they will become free-flowing.

- Reduce the use of pesticides by 50% by 2030.

- Increase organic farming.

- Increase biodiversity in agriculture.

- Reverse the decline of pollinators.

- Give €20 billion per year to the issue and make it part of the business practice.

According to the page, approximately half of the global GDP depends on nature. In Europe many parts of the economy that generate trillions € per year, depend on nature. Currently the benefits of Natura 2000 in Europe contribute €200 - €300 billion per year.[55] Florika Fink-Hooijer, Director General of the Directorate-General for the Environment, said that the EU has the “ambition to be a standard setter" for global biodiversity policy.[56]

Nature Restoration Law

[edit]The Nature Restoration Law is a regulation of the European Union to protect the EU environments and restore its nature to a good ecological state through renaturation. The law is a core element of the European Green Deal and the EU Biodiversity Strategy and makes the targets set therein for the "restoration of nature" binding.[57] EU member states will have to develop their national restoration plans by 2026.[58] They will have to restore at least 30% of habitats in poor condition by 2030, 60% by 2040, and 90% by 2050.[59][60][61]

The regulation is a response to Europe's declining natural environments, with more than 80% of habitats in poor condition.[57] Its goals include protecting the functioning of ecosystem services, climate change mitigation, resilience and autonomy by preventing natural disasters and reducing risks to food security,[57] and restoring damaged ecosystems.[58]

The regulation was proposed by the European Commission on 22 June 2022.[62] The law was adopted in the Council of the European Union on 17 June 2024[67] and was published in the EU's Official Journal on 29 July 2024, thus coming into force on 18 August 2024 (20th day after publication).[68]Sustainable finance

[edit]Motivation

[edit]The main aim of the European Green Deal is to become climate neutral by the year of 2050. The reasons pushing for the plan's creation are based upon the environmental issues such as climate change, a loss of biodiversity, ozone depletion, water pollution, urban stress, waste production and more. The following statistics highlight the climate related issues within the European Union:

- In regards to climate change, carbon dioxide levels are predicted to double by the year of 2030 with Europe's temperature expected to increase by 2-3 °C in the summer season.[69]

- Europe is responsible for nearly one third of the world's gas emissions that deplete the ozone.[69]

- More than 50% of all surface area where ecosystems are in Europe are presented with threats from management problems and stresses.[69]

- On average, 700,000 hectares of woodland are burnt annually by fires “often caused by socioeconomic factors” within the European Union, leading to the degradation of forests.[69]

Clean energy statistics

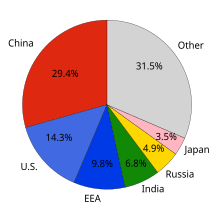

[edit]Global carbon dioxide emissions by country in 2023:

- More than 75% of greenhouse gas emissions are related to the production and use of energy within the EU.[30]

- Positive of renewable resources- Renewable resources sourced 17.5% of the EU's gross energy consumption in 2017.[30]

Sustainable industry statistics

[edit]- Studies showed that from the year of 1970 to 2017, the world's yearly extraction of resources tripled. This process is responsible for 90% of all loss in biodiversity.[70]

- The European Union's current industry is responsible for 20% of their greenhouse gas emissions.[71]

- The current resources that originate from recycling methods is 12% within the European Union's industry.[72]

Building and renovations statistics

[edit]- The building and renovation methods used by the European Union use 40% of all energy consumed.[73]

Farm to fork statistics

[edit]- Within the European Union, “20% of food production is wasted” whilst “36 million of the population are unable to have quality meal every second day.”[46]

Eliminating pollution statistics

[edit]- From the 50,000 industrial locations in the EU, up to €189 billion is spent on health issues related to pollution from these installations.[48]

Sustainable mobility statistics

[edit]- 25% of Greenhouse gas emissions result from transportation methods. Road transport takes 71.7% of this total, followed by 13.9% from Aviation, 13.4% from Water, with railways and other accumulating the remainder.[52]

- The Single European Sky strategy is predicted to help reduce 10% of aviation emissions.[52]

Biodiversity

[edit]

- Within the EU, €40 trillion depends on nature and its resources.[74]

- The population of wild species has declined by over 50% on average in the last two generations.[75]

All 54 actions were adopted or implemented by 2019. The EU is now recognised as a leader in circular economy policy making globally. The waste legislation was adopted in 2018, following negotiations with the European Parliament and Member States in the European Council. According to Eurostat, jobs related to circular economy activities have increased by 6% between 2012 and 2016 within the EU. The action plan has also encouraged at least 14 Member States, eight regions, and 11 cities to put forward circular economy strategies.[76]

Timeline

[edit]- 11 December 2019: The European Green Deal was presented.

- 14 January 2020: The European Green Deal Investment Plan as well as the Just Transition Mechanism were presented.

- 4 March 2020: There was a proposal for a European climate law to ensure a climate neutral European Union by 2050. A public consultation was held on the European Climate Pact (in regards to bringing together regions, local communities, civil society, business and schools).

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen

- 10 March 2020: The European Industrial Strategy was adopted (which is a plan for a future ready economy).

- 11 March 2020: There was a proposal for a Circular Economy Action Plan that focused on sustainable resource use.

- 20 May 2020: The ‘Farm to fork strategy’ was presented in order to increase the sustainability of food systems. The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 was presented which focuses on the protection of fragile natural resources.

- 8 July 2020: Adoption of the EU strategies for energy system integration and hydrogen to pave the way towards a fully decarbonised, more efficient and interconnected energy sector.

- 12 July 2020: The taxonomy for sustainable activities comes into force, to reduce greenwashing and help investors choose green options.[77]

- 17 September 2020: The 2030 Climate Target Plan was presented.[78]

- 9 December 2020: The European Climate Pact was launched.[79]

- 14 July 2021: The "Fit for 55" Package was presented by the European Commission, containing a large number of legislation proposals to achieve the EU Green Deal.[24]

- 5 April 2022: Adoption of several initiatives under the action plan, including:

- legislative proposal for substantiating green claims made by companies

- review of requirements on packaging and packaging waste in the EU

- new policy framework on bio-based, biodegradable and compostable plastics

- measures to reduce the impact of microplastic pollution on the environment.[19]

- 21 December 2024: The European Union Green Bonds Regulation comes into force, allowing the issue of "European Green Bond" (or "EuGB") by companies, regional or local authorities and EEA supra-nationals.[80]

Recovery program from the novel coronavirus

[edit]With the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic spreading rapidly within the European Union, the focus on the European Green Deal diminished. Many leaders including the deputy minister, Kowalski, from Poland, a Romanian politician, and the Czech prime minister, Babiš, suggested either a yearly pause or a complete discontinuation of the deal. Many believe the current main focus of the European Union's current policymaking process should be the immediate, shorter-term crisis rather than climate change.[81]

The financial market being under immense stress along with a reduction in economic activity is another factor threatening to derail the European Green Deal. Public and private funds for the policy as well as the EU's GDP being affected by COVID-19 both hinder the budgeting for the policy to take action.[81]

However, as recovery processes have begun within the European Union, a large majority of ministers are supporting the push for the deal to begin, alongside the subsiding of the first wave of infections. Representatives from 17 governments signed a letter in mid-April pushing for the deal to continue as a “response to the economic crisis while transforming Europe into a sustainable and climate neutral economy.”[82]

In April 2020, the European Parliament called for including the European Green Deal in its economic recovery program.[83][84][85] Ten countries urged the European Union to adopt the “green recovery plan" as fears grew that the economic hit caused by the COVID-19 pandemic could weaken action on climate change.

In May 2020 the leaders of the European Commission argued that the ecological crisis helped create the pandemic, which emphasised the need to advance the European Green Deal.[55][47] Later that month, the €750 billion European recovery package (called Next Generation EU)[86][87] and the €1 trillion budget were announced. The European Green Deal is part of it. The money will be spent only on projects that meet certain green criteria. 25% of all funding will go to climate change mitigation. Fossil fuels and Nuclear power are excluded from the funding. The recovery package is also intended to restore some equilibrium between rich and poor countries in the European Union.[88]

As part of the European Union response to the COVID-19 pandemic, several economic programs were set up, including the CRII, CRII+, European Social Fund+ and REACT-EU[89] With these programs, flexibility is maintained, and CRII and CRII+ are also able to direct money to crisis repair measures through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), European Social Fund (ESF), Fund for European Aid to Most Deprived (FEAD) or the European Social Fund Plus. Some of these programs (such as REACT-EU) also serve to invest in the European Green Deal.

In July 2020, a proposed "Green Recovery Act" in the United Kingdom was published by a think tank and academic group, implementing all recommendations of a “Green New Deal” for Europe (which is distinct from the EU Green Deal)[90] and drawing attention to the fact that "car manufacturers in Europe are far behind China" in ending fossil fuel-based production.[91]

The same month, the recovery package and the budget of the European Union were generally accepted.[by whom? – Discuss] The portion of the money that was allocated for climate action grew to 30%. The plan includes some green taxation on European products and on imports, but critics say it is still not enough for achieving the climate targets of the European Union and it is not clear how to ensure that all the money will really go to green projects.[92]

History of opposition by countries

[edit]Although all EU leaders signed off on the European green deal in December 2019, disagreements in regards to the goals and their timeline to achieve each factor arose. Poland has stated that climate neutrality by 2050 will not be a possibility for their country due to their reliance on coal as their main power source. Their climate minister, Michał Kurtyka, declared that commitments and funds need to be more fairly allocated.[93] The initiative to increase the goal of lowering carbon emissions split the EU, with the coal reliant countries such as Poland complaining it will affect “jobs and competitiveness.”[93] Up to 41,000 jobs could be lost within Poland, with the Czech Republic, Bulgaria and Romania also having a possible loss of 10,000 jobs each.[94] Czech Prime Minister, Andrej Babiš, stated that their nation will not reach the 2050 goal “without nuclear” association.[95] Countries are also arguing over the Just Transition Fund (JTF) that aims to help countries who are reliant on coal to become more environmentally friendly.[96] These countries that changed their impacts prior to the Policy, such as Spain, believe that the JTF is unfair as it only benefits the countries that didn't "go green earlier."[93] The head of Brussels' office of the Open Europe think tank, Pieter Cleppe, further dismissed the plan with sarcastic comment, “What could possibly go wrong.”[95]

Poland's Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said that the EU's carbon pricing system unfairly disadvantages poorer countries in Southern and Eastern Europe.[97] Speaking at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, Czech Prime Minister Babiš denounced the European Green Deal,[98] saying that the European Union "can achieve nothing without the participation of the largest polluters such as China or the USA that are responsible for 27 and 15 percent, respectively, of global CO2 emissions."[99]

In August 2023, the Polish government filed a series of complaints with the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) against provisions that are part of the Fit for 55 package, claiming that three EU climate policies threaten Poland's economy and energy security.[100] In February 2024, responding to protests by Polish farmers, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk declared that he would advocate for changes in the European Green Deal.[101] In March 2024, Tusk insisted that Poland would go its own way "without European coercion".[102]

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni criticized the EU ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2035 that would "condemn [Europe] to new strategic dependencies, such as China's electric [vehicles]." Meloni said, "Reducing polluting emissions is the path we want to follow, but with common sense."[103]

Analysis and criticism

[edit]Initial European Green Deal

[edit]It has been found that American oil company ExxonMobil had a significant impact on the early negotiations of the European Green Deal. ExxonMobil attempted to change the deal in a way that puts less emphasis on the importance of reducing transport that emits carbon dioxide. This was only one of many opponents of the deal.[104]

The European Green Deal has faced criticism from some EU member states, as well as non-governmental organizations. Greenpeace has argued that the deal is not drastic enough and that it will fail to slow down climate change to an acceptable degree.[105] The Corporate Europe Observatory calls the Deal a positive first step, but criticizes the influence the fossil fuel industry had on it.[106]

There has been criticism of the deal not doing enough, but also of the deal potentially being destructive to the European Union in its current state. Former Romanian president, Traian Băsescu, has warned that the deal could lead to some EU members to push towards an exit from the union. While some European states are on their way to eliminating the use of coal as a source of energy, many others still rely heavily on it.[107] This scenario demonstrates how the deal may appeal to some states more than others. The economic impact of the deal is likely to be unevenly spread among EU states. This was highlighted by Polish MEP, Ryszard Legutko, who asked, “is the Commission trying to seize power from the member states?”.[108] Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary, three states that depend mostly on coal for energy, were the most opposed to the deal. Young climate activist Greta Thunberg commented on governments opposing the deal, saying "It seems to have turned into some kind of opportunity for countries to negotiate loopholes and to avoid raising their ambition".[109]

In addition, many groups such as “Greenpeace”, “Friends of the Earth Europe” and the “Institute for European Environmental Policy” have all analysed the policy and believe it isn't “ambitious enough.”[95] Greenpeace believes the plan is “too little too late”[110] whilst the IEEP stated that most prospects of meeting policy objectives “lacked clear or adequate” goals for the problem areas.[111]

The Greens-European Free Alliance and Jytte Guteland have proposed that the European Green Deal's EU 2030 climate target were to be raised to at least 65% greenhouse gas emissions reductions.[112][113][114]

The EU has acknowledged these issues, however, and through the “Just Transition Mechanism”, expects to distribute the burden of transitioning to a greener economy more fairly. This policy means that countries that have more workers in coal and oil shale sectors, as well as those with higher greenhouse emissions, will receive more financial aid.[16] According to Frans Timmermans, this mechanism will also make investment more accessible for those most affected, as well as offering a support package, which will be worth “at least 100 billion euros”.[115] The Mechanism, a part of the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan, is expected to mobilize €100 billion in investments during the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), with funding from the EU budget and Member States, as well as contributions from InvestEU and the European Investment Bank.[116][117]

The Just Transition Mechanism provides a comprehensive set of support options for the most vulnerable regions. The Just Transition Fund, the first pillar, will provide €17.5 billion in EU grants available to the most affected territories, implying a national co-financing requirement of around €10 billion. The second pillar creates a specialized transition plan under InvestEU to leverage private investment. Finally, a new public sector credit facility is formed under the third pillar to leverage public finance. These measures will be accompanied by specialized advisory and technical assistance for the affected regions and projects.[118][119]

The European Investment Bank Group will be able to support this through Structural Programme Loans in conjunction with European structural and investment funds (ESIF) co-financing operations.[120]

At COP26, the European Investment Bank announced a set of just transition common principles agreed upon with multilateral development banks, which also align with the Paris Agreement. The principles refer to focusing financing on the transition to net zero carbon economies, while keeping socioeconomic effects in mind, along with policy engagement and plans for inclusion and gender equality, all aiming to deliver long-term economic transformation.[121] Until 2030, the European Investment Bank announced that it is prepared to mobilise $1 trillion for climate action.[9][122]

The African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, Islamic Development Bank, Council of Europe Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, New Development Bank, and Inter-American Development Bank are among the multilateral development banks that have vowed to uphold the principles of climate change mitigation and a Just Transition. The World Bank Group also contributed.[121][123][124]

Fossil fuels

[edit]The current proposals have been criticised for falling short of the goal of ending fossil fuels, or being sufficient for a green recovery after the COVID-19 pandemic.[125] The European Environmental Bureau as well as the International Energy Agency (IEA) stated that fossil fuel subsidies would need to end. However, it should be stated that this can not be done until 2021, when the Energy Taxation Directive is to be revised. Also, while fossil fuels are still actively being subsidized by the EU until 2021, even during an economic recession, it is also already working on supporting electrification of vehicles and green fuels such as hydrogen.

Environmental effects of electric cars

[edit]

Nickel and cobalt are the basic commodities used in almost every electric vehicle battery.[127] Open-pit nickel mining has led to environmental degradation and pollution in developing countries such as the Philippines and Indonesia.[128][129] In 2024, nickel mining and processing was one of the main causes of deforestation in Indonesia.[130][131]

Open-pit cobalt mining has led to deforestation and habitat destruction in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[132]

The European Environmental Bureau and Friends of the Earth Europe published a report analysing the European Green deal. According to the report, it will not be enough to change energy sources for reaching a sustainable society because EVs, wind, solar energy require a high rate of resource consumption while the mining process is associated with high societal and environmental damage. The report says: "With respect to environmental impacts from resource use, the EU uses between 70% and 97% of the ‘safe operating space’ available for the whole world. This means the EU alone is close to exceeding the planetary boundaries for resource use impacts, beyond which the stable functioning of the earth’s biophysical systems are in jeopardy." The report proposes among others, creating binding targets for reducing resource consumption, shrinking economic sectors with little or no societal benefits (military, aerospace, fast fashion, cars), protecting areas and people from mining, and creating a sharing economy.[133]

Job losses and inflation

[edit]Trade unions warned that the European Green Deal will put 11 million jobs at risk.[134][135] The Commission predicts that 180,000 jobs could be lost in the coal mining industry by 2030. A 2021 study estimates that the automotive industry could lose half a million jobs.[136]

The EU’s carbon pricing scheme for road and heating fuels (ETS2) will lead to an increase in the price of fossil fuels such as heating gas, petrol and diesel. The ETS2 will become fully operational in 2027.[137][138]

The European Green Deal could reduce Europe's agricultural production and increase global food prices.[139]

In July 2023, European People's Party (EPP) leader Manfred Weber tried to block the Nature Restoration Law, saying it would destroy farmers' livelihoods and threaten food security.[140]

2021–2023 global energy crisis

[edit]

Due to a combination of unfavourable conditions, which involved soaring demand of natural gas, its diminished supply from Russia and Norway to the European markets, less power generation by renewable energy sources such as wind, water and solar energy, and cold winter that left European and Russian gas reservoirs depleted, Europe faced steep increases in gas prices in 2021.[142][143][144][145][146][147] Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán blamed a record-breaking surge in energy prices on the European Commission's Green Deal plans.[148] Politico reported that "Despite the impact of high energy prices, [EU Commissioner for Energy] Simson insisted that there are no plans to backtrack on the bloc's Green Deal".[149] European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said that "Europe today is too reliant on gas and too dependent on gas imports. The answer has to do with diversifying our suppliers ... and, crucially, with speeding up the transition to clean energy."[150][151]

Energy-intensive German industry and German exporters were hit particularly hard by the energy crisis.[141]

2024 European farmers' protests

[edit]

European farmers have protested against proposed environmental regulations (such as a carbon tax, pesticide bans, nitrogen emissions curbs and restrictions on water and land usage), low food prices and trade in agricultural products with non-European Union member states, such as Ukraine and the Mercosur bloc of South America.[152][153]

Academic analysis

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2023) |

A meta-analysis from 2023 reported results about "required technology-level investment shifts for climate-relevant infrastructure until 2035" within the EU, and found these are "most drastic for power plants, electricity grids and rail infrastructure", ~87€ billion above the planned budgets in the near-term (2021–25), and in need of sustainable finance policies.[154][155]

The European Union Emissions Trading System should be expanded to more sectors is proposed in a paper from Bruegel.[156]

Bioeconomy

[edit]In 2024, over 60 NGOs sent a letter to the European Union expressing a concern about the bioeconomy concept "explicitly referenced in the European Green Deal". According to the organizations, it puts strong pressure on ecosystems, while in the same European Green Deal, one of the targets is to protect 30% of land and waters and to restore ecosystems. The authors argue that "moving from fossil to bio sources without embedding it in a wider socio-ecological transformation and drastically reducing consumption would be a disaster."[157][158]

May 2024 analysis

[edit]In May 2024, a report has been published, summarizing the main achievements of the European Union in the environmental domain from 2019, with an emphasis on the green new deal. The report says that without this set of policies, the environmental situation was worse but the world is still on track to 2.9 degrees warming.[159]

New European Bauhaus

[edit]The New European Bauhaus is an artistic movement initiated by the European Commission, more precisely by the President of the European Commission, Mrs. Ursula von der Leyen herself. Its aim is to implement the European Green Deal through culture by integrating esthetics, sustainability and inclusiveness.

The New European Bauhaus (NEB) is an interdisciplinary movement which intends to re-express the fundamental ambitions of the historical Bauhaus movement generated by the German architect Walter Gropius, in order to deal with contemporary issues from the fields of creation: art, crafts, design, architecture and urban planning.

The New European Bauhaus being "new" it is currently still being developed by a multicultural and international Research Committee headed by an artist, Alexandre Dang.

However the name who has been chosen is strongly criticized in some artistic communities as being "inherently not inclusive".[160]

Phases

[edit]This movement wanting to be as open and accessible as possible, this will be facilitated by a planification in three phases: the Design phase (2020-2021), the Delivery phase (2021-2023+) and the Dissemination phase (2023-2024+).[161]

The Design phase

[edit]As a first step, the Design phase was about finding methods that could boost existing ideas related to the NEB's challenges, regarding culture and technology. These two notions are considered by the New European Bauhaus as determinant elements to face contemporary concerns, especially in architecture and urban planning sectors.[162] By launching a call for proposals, acceleration services and financial contribution started to be provided to some projects under European Union funding programs, such as Horizon Europe or LIFE programme, but also international organisations.[163]

In the idea of a collective design dynamic, a "High-level roundtable" has been set up with 18 thinkers and practitioners, involving for example famous architects Shigeru Ban and Bjark Ingels, the President of the Italian National Innovation Fund Francesca Bria, the activist and academic Sheela Patel, and others.[164]

The Delivery phase

[edit]After the Design phase, the Communication of the European Commission "New European Bauhaus Beautiful, Sustainable, Together" was released on 15 September 2021.[165] The detailed content of this communication directly led to the Delivery phase, which began by setting up five pilots projects. These projects were selected as flagship proposals for the NEB's announced goal: "a sustainable green transformation in housing, architecture, transportation, urban, and rural spaces as part of its effort to reach carbon neutrality by 2050".[166] In fact, one of the fundamental points of the New European Bauhaus, that is put forward by the European Commission, is to translate the European Green Deal, officially approved in 2020, to make it a tangible cultural experience in which citizens from all around the world could participate.[167]

Referring to the major principles of the original Bauhaus movement, the NEB initiative wants to be multi-level: "from global to local, participatory and transdisciplinary".[165] By initiating a co-design process, views and experiences of thousands of citizens, professionals and organisations across the EU, and beyond, were involved into open conversations. Emerging from this collective thinking, the three terms highlighted to define the movement are "Sustainability" (including climate goals, circularity, zero pollution and biodiversity), "Aesthetics" (quality of experience and style, beyond functionality) and "Inclusion" (including diversity first, securing accessibility and affordability).[168] The four thematic axes chosen to guide the NEB's implementation for the next years are "Reconnecting with nature", "Regaining a sense of belonging", "Prioritising the places and people that need it most", and "Fostering long term, life cycle thinking in the industrial ecosystem".[169] The three levels of interconnected transformations expected from the initiative are "changes in places around us", "changes in the environment that enable innovation" and "changes in the diffusion of new meanings".[170]

The Dissemination phase

[edit]During the Dissemination phase, the New European Bauhaus planned to focus on spreading chosen ideas and concepts to a broader audience, not only inside the EU.[171][172] Within the three-phases development, this last step should be about networking and sharing knowledge between practitioners on available methods, solutions and prototypes, but also, it is meant to help creators to replicate their experiences across cities, rural areas and localities and to influence the new generation of architects and designers.[173]

New European Bauhaus prizes

[edit]In spring 2021, the European Commission launched New European Bauhaus prizes to reward inspiring examples of the realizations fitting the NEB principles. For the first edition of the contest, Commissioners Ferreira and Gabriel awarded 20 projects in a ceremony in Brussels on 16 September 2021.[174] A second edition of NEB prizes is taking place in 2022.[175]

The NEB LAB

[edit]The NEB LAB, or New European Bauhaus Laboratory, has been established as a meeting space to work with the New European Bauhaus growing community, which is more than 450 official partners, High-Level Roundtable members, Contact Points of the national governments, and winners and finalists of the New European Bauhaus prizes. The NEB LAB's main objective is to put the movement's thinking into practice, by co-creating and testing solutions and policy actions, like the development of labeling tools. It has started with a "Call for Friends of the New European Bauhaus", in order to get public entities, companies and political organisations involved.[176]

The New European Bauhaus Festival

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (June 2024) |

The opening of a New European Bauhaus Festival has been announced by the European Commission to allow visibility for creators, to encourage them to "showcase" their ideas and share their progress, but also to enable networking and to foster citizen engagement. It will stand on three pillars: Fair (presentation of completed projects or products), Fest (the cultural section, with artists and performance) and Forum (debates with innovative participatory formats).[177]

Its first edition will take place on 9–12 June 2022 in Brussels.[178] Based on this experience, the commission will draw up a concept for a yearly event that will include places in and outside the EU from 2023 onwards.

See also

[edit]- A Green New Deal

- Anti-Waste and Circular Economy Law

- Build Back Better Plan

- Carbon neutrality

- EU Allowance

- EU Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability Towards a Toxic-Free Environment

- COVID-19 economic recovery programmes

- Sustainable finance

- Environmental impact of agriculture

- Green economy

- Paris Agreement

References

[edit]- ^ Tamma, Paola; Schaart, Eline; Gurzu, Anca (11 December 2019). "Europe's Green Deal plan unveiled". POLITICO. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Simon, Frédéric (11 December 2019). "EU Commission unveils 'European Green Deal': The key points". euractiv.com. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Rankin, Jennifer (13 December 2019). "European Green Deal to press ahead despite Polish targets opt-out". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Benakis, Theodoros (15 January 2020). "Parliament supports European Green Deal". European Interest. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Higham, Catherine; Setzer, Joana; Narulla, Harj; Bradeen, Emily (March 2023). Climate change law in Europe: What do new EU climate laws mean for the courts? (PDF) (Report). Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. p. 3. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "International investors enter Poland renewable energy market after rule change". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Geden, Oliver; Schenuit, Felix; Stiftung Wissenschaft Und Politik (2020). "Unconventional Mitigation". SWP Research Paper. doi:10.18449/2020RP08. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ "€33 trillion investor group: strong EU climate targets key to economic recovery & future growth". IIGCC. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "Europe needs to forge ahead with renewable energy". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ "Fit for 55". consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ Jaeger, Carlo; Mielke, Jahel; Schütze, Franziska; Teitge, Jonas; Wolf, Sarah (2021). "The European Green Deal – More Than Climate Neutrality". Intereconomics. 2021 (2): 99–107.

- ^ "Net Zero Coalition". United Nations. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ Mathiesen, Karl; Weise, Zia; Lynch, Suzanne (22 August 2023). "Šefčovič replaces Timmermans as EU Green Deal chief". Politico Europe. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ "What is the European Climate Pact?". European Climate Pact. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "European Climate Pact". CDP. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "Financing the green transition: The European Green Deal Investment Plan and Just Transition Mechanism". European Commission. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Valatsas, Dimitris (17 December 2019). "Green Deal, Greener World". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism". European Parliament.

- ^ a b c "EUR-Lex - 52020DC0098 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. 2020.

- ^ "Circular economy action plan". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS" (PDF).

- ^ Bank, European Investment (14 December 2020). The EIB Group Climate Bank Roadmap 2021-2025. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-4908-5.

- ^ "EUROPE'S BUILDINGS UNDER THE MICROSCOPE" (PDF).

- ^ a b "European Green Deal: Commission proposes transformation of EU economy and society to meet climate ambitions". European Commission. 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "UNEP: Emissions Gap Report 2020" (PDF).

- ^ Heil, Mark T.; Wodon, Quentin T. (1997). "Inequality in CO₂ Emissions Between Poor and Rich Countries". The Journal of Environment & Development. 6 (4): 426–452. doi:10.1177/107049659700600404. ISSN 1070-4965. JSTOR 44319289. S2CID 153901525.

- ^ Haines, Andy; Scheelbeek, Pauline (2020). "European Green Deal: a major opportunity for health improvement" (PDF). The Lancet. 395 (10233): 1327–1329. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30109-4. PMID 32394894. S2CID 211091322.

- ^ a b c d Simon, Frédéric (12 December 2019). "The EU releases its Green Deal. Here are the key points". Climate Home News. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Clean Energy". European Commission. 11 December 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "EU Strategy for Energy System Integration" (PDF). 18 August 2023.

- ^ Pollet, Mathieu (10 July 2020). "Explainer: Why is the EU betting on hydrogen for a greener future?". euronews.

- ^ CORKE, Mai Ling (6 July 2020). "European Clean Hydrogen Alliance". Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs - European Commission.

- ^ "The scale-up gap: Financial market constraints holding back innovative firms in the European Union". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ "Industrial Policy". European Commission. 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "Sustainable Industry". European Commission. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d "The essentials of the "Green Deal" of the European Commission". Green Facts. 7 January 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "European Green Deal Communication" (PDF).

- ^ "Commission's "Green Deal" could lead to ban on EU waste exports | EUWID Recycling and Waste Management". www.euwid-recycling.com. 11 December 2019.

- ^ "EU says higher climate goal requires €350B extra energy investment per year". spglobal.com. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ "Europe's path to decarbonization". McKinsey. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ "Building and Renovating". European Commission. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (5 May 2022). Digitalisation in Europe 2021-2022: Evidence from the EIB Investment Survey. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5233-7.

- ^ "The potential of digital business models in the new energy economy – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "From Farm to Fork". European Commission. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b Spencer, Natasha (17 March 2020). "EU's 'farm to form' strategy aims to feed sustainable food system". Food Navigator. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "From Farm to Fork". European Commission website. European Union. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ a b c Schaible, C. (2020). EU Industrial Strategy for Achieving the ‘Zero Pollution’ Ambition Set with the EU Green Deal (Large Industrial Activities). Brussels: European Environmental Bureau.

- ^ "Eliminating pollution". European Commission. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "Viewpoint: 'The European Green Deal has been captured by chemophobic activists with no understanding of science'. Here's how the EU can put sustainability ahead of ideology". Genetic Literacy Project. 23 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "Legislative train schedule". European Parliament.

- ^ a b c d "Sustainable mobility". European Commission. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Single European Sky". European Commission. 21 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ a b "EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030". European Commission. 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030". European Commission website. European Union. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ "'Be sustainable or be irrelevant': Green week begins with call for food revolution". www.endseurope.com. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "The EU #NatureRestoration Law". environment.ec.europa.eu. 12 July 2024. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ a b "State of the Union: EU top jobs and Nature Restoration law". euronews. 21 June 2024. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Nature restoration: Parliament adopts law to restore 20% of EU's land and sea | News | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 27 February 2024. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Nature restoration". Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ a b Manzanaro, Sofia Sanchez (17 June 2024). "EU countries rubberstamp Nature Restoration Law after months of deadlock". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Nature restoration law - European Commission". environment.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ "Österreich gab bei Ja zu Renaturierungsgesetz den Ausschlag, Nehammer kündigt Nichtigkeitsklage an". DER STANDARD (in Austrian German). Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "EU ministers approve contested Nature Restoration Law – DW – 06/17/2024". dw.com. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Petrequin, Samuel (17 June 2024). "EU approves landmark nature restoration plan despite months of protests by farmers". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Nature restoration law: Council gives final green light". Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ [63][64][65][61][66]

- ^ "2022/0195(COD)". Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Problems". European Environment Agency. 20 April 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Global Resources Outlook". International Resource Panel. 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ "European Commission. (2019). EU Climate Action Progress Report. Brussels: European Commission" (PDF).

- ^ "Circular material use rate". Eurostat. European Commission. 2020. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Energy Balances Sheet". Eurostat. European Commission. 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Factsheet: EU 2030 Biodiversity Strategy". European Commission. 20 May 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Brown, Elizabeth Anne (1 November 2018). "Widely misinterpreted report still shows catastrophic animal decline". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "The EU's Circular Economy Action Plan". ellenmacarthurfoundation.org. 12 January 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "EU taxonomy for sustainable activities". European Commission. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "A European Green Deal". European Commission. 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "The European Climate Pact: empowering citizens to shape a greener Europe". European Commission. 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Pellicani, Nicholas P. (20 February 2024). "EU Green Bonds Regulation". Debevoise & Plimpton. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ a b Elkerbout, M., Egenhofer, C., Núñez Ferrer, J., Cătuţi, M., Kustova, I., & Rizos, V. (2020). The European Green Deal after Corona: Implications for EU climate policy. Brussels: CEPS.

- ^ Alister, Alister (20 April 2020). "Four more EU nations back a green post-coronavirus recovery". Climate Home News. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19: MEPs call for massive recovery package and Coronavirus Solidarity Fund". European Parliament. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Simon, Frédéric (27 March 2020). "EU leaders back 'green transition' in pandemic recovery plan".

- ^ Abnett, Kate (9 April 2020). "Ten EU countries urge bloc to pursue 'green' coronavirus recovery". Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "EU recovery fund's debt-pooling is massive shift for bloc". Euronews. 28 May 2020.

- ^ "EU's financial 'firepower' is 1.85 trillion with 750bn for COVID fund". Euronews. 27 May 2020.

- ^ Simon, Frédéric (27 May 2020). "'Do no harm': EU recovery fund has green strings attached". Euroactive. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission.

- ^ "A Blueprint for Europe's Just Transition". Green New Deal for Europe. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ E McGaughey, M Lawrence and Common Wealth, 'The Green Recovery Act 2020 Archived 2020-07-15 at the Wayback Machine', proposed UK law, and pdf

- ^ Abnett, Kate (21 July 2020). "Factbox: How 'green' is the EU's recovery deal?". Reuters. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Oroschackoff, Kalina; Hernandez-Morales, Aitor (3 April 2020). "EU climate law sparks political battles". Politico. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Claeys, G., Tagliapietra, S., & Zachmann, G. (2019). How to make the European Green Deal work. Bruegel.

- ^ a b c Kelly, Eanna (12 December 2019). "EU Council meets to debate Green Deal grand plan for tackling climate change". Science Business. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Voet, Ludovic (3 December 2019). "A Just Transition Fund: one step on a long march". Social Europe. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Poland's resistance leads to EU leaders' climate battle retreat". Politico. 25 May 2021.

- ^ "COP26: Babiš to focus on European energy crisis, EU Green Deal's economic impact". Czech Radio. 1 November 2021.

- ^ "Andrej Babiš: It is absolutely crucial for individual states to choose their own energy mix to achieve carbon neutrality". Government of the Czech Republic. 1 November 2021.

- ^ "Poland files lawsuit against key EU climate policies". Euractiv. 29 August 2023.

- ^ "Tusk Says He'll Seek EU Green Deal Changes to Alleviate Farmers". Bloomberg. 29 February 2024.

- ^ "EU Council position hardens against Nature Restoration Law". Euractiv. 5 April 2024.

- ^ "Italy's Meloni denounces 'ideological madness' of EU ban on gas and diesel cars". Politico. 26 June 2024.

- ^ "ExxonMobil attempts to influence the European Green Deal". Influence Map. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Leaked European Green Deal is not up to the task, Greenpeace". Greenpeace. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "A grey deal?". Corporate Europe Observatory. 7 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Simon, Frédéric (20 February 2020). "Basescu: European Green Deal risks pushing 'two or three countries' towards EU exit". Euractiv. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Green deal for Europe: First reactions from MEPs". European Parliament. 12 November 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Sean (7 February 2020). "Here's how Europe plans to be the first climate-neutral continent". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "European Green Deal misses the mark". Greenpeace. Greenpeace European Unit. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Institute for European Environmental Policy . (2019). First Analysis of the European Green Deal. Institute for European Environmental Policy.

- ^ "10 priority measures to save the climate". Greens/EFA.

- ^ "EU must take the lead with more ambitious climate targets". Greens/EFA.

- ^ Simon, Frédéric (29 April 2020). "EU lawmaker puts 65% emissions cut on the table".

- ^ "Allocation method for the Just Transition Fund". European Commission. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "The Just Transition Mechanism platform helps EU countries and regions with their journey to climate neutrality". clustercollaboration.eu. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ "The Just Transition Mechanism: making sure no one is left behind". European Commission.

- ^ "Just Transition funding sources". European Commission.

- ^ "Just Transition Mechanism: the EIB and the European Commission join forces in a proposed new public loan facility to finance green investments in the EU". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ "A €17.5 bn fund to ensure no one is left behind on the road to a greener economy". European Parliament. 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ a b European Investment Bank. (6 July 2022). EIB Group Sustainability Report 2021. European Investment Bank. doi:10.2867/50047. ISBN 978-92-861-5237-5.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (29 January 2020). ">€1 TRILLION FOR". European Investment Bank.

- ^ "Multilateral Development Banks". African Development Bank. 12 April 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Collective Climate Ambition — A Joint Statement at COP26 by the Multilateral Development Banks". Asian Development Bank. 5 November 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ European Environmental Bureau, 'EU plans multi-billion euro ‘green recovery’ but falls short in crucial areas' (27 May 2020) eeb.org. Friends of the Earth Europe, 'EU Green Deal: fails to slam on the brakes' (11 December 2019). E McGaughey, M Lawrence and Common Wealth, 'The Green Recovery Act 2020 Archived 2020-07-15 at the Wayback Machine', proposed UK law, and pdf

- ^ "Batteries and secure energy transitions". Paris: IEA. 2024.

- ^ "Commodities Used in Electric Car Batteries: An Update on Lithium and Nickel". Resilinc. 1 November 2023.

- ^ Rick, Mills (4 March 2024). "Indonesia and China killed the nickel market". MINING.COM.

- ^ "Land grabs and vanishing forests: Are 'clean' electric vehicles to blame?". Al Jazeera. 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Indonesia's massive metals build-out is felling the forest for batteries". AP News. 15 July 2024.

- ^ "EU faces green dilemma in Indonesian nickel". Deutsche Welle. 16 July 2024.

- ^ "How 'modern-day slavery' in the Congo powers the rechargeable battery economy". NPR. 1 February 2023.

- ^ ‘Green mining’ is a myth: The case for cutting EU resource consumption (PDF). Brussels, Belgium: European Environmental Bureau, Friends of the Earth Europe. pp. 1–5. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ "Eleven million jobs at risk from EU Green Deal, trade unions warn". Euractiv. 9 March 2020.

- ^ "The false promise of green jobs". The Economist. 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Does the architect of Europe's Green Deal truly understand what he's unleashed?". Politico. 16 November 2023.

- ^ "Fossil fuel could rise by nearly 40 cents in 2027". Eesti Rahvusringhääling. 30 October 2023.

- ^ "New EU scheme could hike petrol, gas prices higher than expected, key lawmakers admit". Euractiv. 13 May 2024.

- ^ "EU Green Deal set to impact international food prices". Farm Weekly. 31 October 2023.

- ^ "EU conservatives' anti-Green Deal push falls short". Politico. 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b "As Europe Deindustrializes, Can Economic Suicide Be Avoided?". Forbes. 10 May 2024.

- ^ "EU countries look to Brussels for help with 'unprecedented' energy crisis". Politico. 6 October 2021.

- ^ "Europe's Power Crisis Moves North as Water Shortage Persists". Bloomberg. 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Russia says it could boost supplies to ease Europe gas costs". Associated Press. 7 October 2021.

- ^ "It is tempting to blame foreigners for Europe's gas crisis: The main culprit is closer to home". The Economist. 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Russia Has a Gas Problem Nearly the Size of Exports to Europe". Bloomberg. 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Energy crisis: The blame game has begun - but are some of the claims just hot air?". Sky News. 22 September 2021.

- ^ "The Green Brief: East-West EU split again over climate". Euractiv. 20 October 2021.

- ^ "Putin promises gas to a Europe struggling with soaring prices". Politico. 13 October 2021.

- ^ "EU chief says key to energy crisis is pushing Green Deal". Associated Press. 20 October 2021.

- ^ "Europe's energy crisis: Continent 'too reliant on gas,' says von der Leyen". Euronews. 20 October 2021.

- ^ "Polish farmers protest against Ukrainian imports and EU Green Deal". euronews. 15 March 2024.

- ^ Liakos, Sophie Tanno, Chris (3 February 2024). "Farmers' protests have erupted across Europe. Here's why". CNN.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Studie sieht EU-weit 87 Milliarden Euro Mehrbedarf bei Erneuerbaren und E-Verkehr". MDR.DE (in German). Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Klaaßen, Lena; Steffen, Bjarne (January 2023). "Meta-analysis on necessary investment shifts to reach net zero pathways in Europe". Nature Climate Change. 13 (1): 58–66. Bibcode:2023NatCC..13...58K. doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01549-5. hdl:20.500.11850/594937. ISSN 1758-6798. S2CID 255624692.

- Expert reviews of the study: "Notwendige Investitionen auf dem Weg zu Netto-Null-Emissionen". sciencemediacenter.de. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Pisani-Ferry, Jean; Tagliapietra, Simone; Zachmann, Georg (6 September 2023). "A new governance framework to safeguard the European Green Deal". Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ "Joint statement on biomass and forestry: Bioeconomy leads to further ecosystem exploitation". European Environmental Bureau. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ NGOs raise concerns: Bioeconomy leads to further ecosystem exploitation (PDF). Bioeconomy Action Forum. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "What has the EU done for the planet and its citizens?". European Federation for Transport and Environment AISBL. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ "Objections to the term New European Bauhaus". 2021.

- ^ "Key Concepts of the New European Bauhaus" (PDF). europa.eu.

- ^ "Le patrimoine au cœur des enjeux européens". cnrs.fr (in French). 11 March 2022.

- ^ "The British Council is looking to join project proposals for Horizon Europe's 'New European Bauhaus'". unica-network.eu. 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Shigeru Ban, Bjarke Ingels Among Names For New European Bauhaus' High-Level Roundtable". worldarchitecture.org. 15 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee of the Regions: New European Bauhaus Beautiful, Sustainable, Together". eur-lex.europa.eu. 15 September 2021.

- ^ "New Bauhaus contest kicks off to inspire green projects". euobserver.com. 23 April 2021.

- ^ "The new European Bauhaus Initiative adds culture to the Green Deal". brusselstimes.com. 23 June 2021.

- ^ "Call for proposals: Scaling the New European Bauhaus Ventures". climate-kic.org. 18 October 2021.

- ^ "New European Bauhaus Initiative". iflaeurope.eu. September 2021.

- ^ Troussard, Xavier (2021). "#NewEuropeanBauhaus". territoriall.espon.eu.

- ^ Ilaria Totaro, Antonella (11 October 2021). "WHAT IS THE NEW EUROPEAN BAUHAUS?". renewablematter.eu.

- ^ "Could the New European Bauhaus inspire the UK ?". creativereview.co.uk. 9 February 2021.

- ^ "New European Bauhaus: Commission launches design phase". ec.europa.eu. 18 January 2021.

- ^ "From Spain to Denmark: New European Bauhaus 2021 Announces 20 Awarded Projects". archdaily.com. 19 November 2021.

- ^ Cuffe, Ciarán (7 April 2022). "The New European Bauhaus". energytransition.org.

- ^ "New European Bauhaus: Commission launches 'NEB LAB' with new projects and call for Friends". ec.europa.eu. 7 April 2022.

- ^ "New European Bauhaus to celebrate creative ideas with a Festival". themayor.eu. 21 February 2022.

- ^ "The Festival - European Union". new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu. 10 April 2024.

Sources

[edit]- The European Green Deal. Brussels: European Commission. 2019.

- The European Green Deal - ANNEX. Brussels: European Commission. 2019.

- European Green Deal Investment Plan (PDF). Brussels: European Commission. 2020.

External links

[edit]- A European Green Deal by the European Commission

- E McGaughey, M Lawrence and Common Wealth, 'The Green Recovery Act 2020 Archived 2020-07-15 at the Wayback Machine', a proposed UK law, and pdf

- Green New Deal for Europe (2019) Edition II, foreword by Ann Pettifor and Bill McKibben

- New European Bauhaus official website by the European Union

- "New European Bauhaus initiative" by the European Parliament

- "New European Bauhaus initiative" by IFLA Europe – International Federation of Landscape Architects

- "WHAT IS THE NEW EUROPEAN BAUHAUS?" by Renewable Matter

- What is the New European Bauhaus? | With Xavier Troussard

- New European Bauhaus: Adaptive reuse of cultural heritage