Council of the European Union

Council of the European Union

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Founded | 1 July 1967 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leadership | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Structure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Seats | 27 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Committees | 10 configurations

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United in Diversity | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Meeting place | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Europa building Brussels, Belgium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| European Convention Center Luxembourg City, Luxembourg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| consilium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constitution | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Treaties of the European Union | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

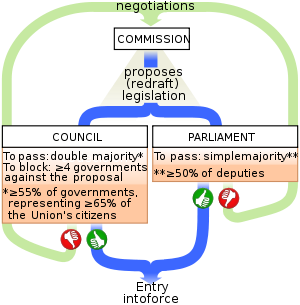

The Council of the European Union, often referred to in the treaties and other official documents simply as the Council,[a] and informally known as the Council of Ministers, is the third of the seven Institutions of the European Union (EU) as listed in the Treaty on European Union.[2] It is one of two legislative bodies and together with the European Parliament serves to amend and approve, or veto, the proposals of the European Commission, which holds the right of initiative.[3][4][5]

The Council of the European Union and the European Council are the only EU institutions that are explicitly intergovernmental, that is, forums whose attendees express and represent the position of their Member State's executive, be they ambassadors, ministers or heads of state/government.

The Council meets in 10 different configurations of 27 national ministers (one per state). The precise membership of these configurations varies according to the topic under consideration; for example, when discussing agricultural policy the Council is formed by the 27 national ministers whose portfolio includes this policy area (with the related European Commissioners contributing but not voting).

Composition

[edit]The Presidency of the Council rotates every six months among the governments of EU member states, with the relevant ministers of the respective country holding the Presidency at any given time ensuring the smooth running of the meetings and setting the daily agenda.[6] The continuity between presidencies is provided by an arrangement under which three successive presidencies, known as Presidency trios, share common political programmes. The Foreign Affairs Council (national foreign ministers) is however chaired by the Union's High Representative.[7]

Its decisions are made by qualified majority voting in most areas, unanimity in others, or just simple majority for procedural issues. Usually where it operates unanimously, it only needs to consult the Parliament. However, in most areas the ordinary legislative procedure applies meaning both Council and Parliament share legislative and budgetary powers equally, meaning both have to agree for a proposal to pass. In a few limited areas the Council may initiate new EU law itself.[6]

The General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union, also known as Council Secretariat, assists the Council of the European Union, the Presidency of the Council of the European Union, the European Council and the President of the European Council.[8] The Secretariat is headed by the Secretary-General of the Council of the European Union.[9] The Secretariat is divided into eleven directorates-general, each administered by a director-general.[10]

History

[edit]The Council first appeared in the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) as the "Special Council of Ministers", set up to counterbalance the High Authority (the supranational executive, now the Commission). The original Council had limited powers: issues relating only to coal and steel were in the Authority's domain, and the Council's consent was only required on decisions outside coal and steel. As a whole, the Council only scrutinised the High Authority (the executive). In 1957, the Treaties of Rome established two new communities, and with them two new Councils: the Council of the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC) and the Council of the European Economic Community (EEC). However, due to objections over the supranational power of the Authority, their Councils had more powers; the new executive bodies were known as "Commissions".[11]

In 1965, the Council was hit by the "empty chair crisis". Due to disagreements between French President Charles de Gaulle and the Commission's agriculture proposals, among other things, France boycotted all meetings of the Council. This halted the Council's work until the impasse was resolved the following year by the Luxembourg compromise. Although initiated by a gamble of the President of the Commission, Walter Hallstein, who later on lost the Presidency, the crisis exposed flaws in the Council's workings.[12]

Under the Merger Treaty of 1967, the ECSC's Special Council of Ministers and the Council of the EAEC (together with their other independent institutions) were merged into the Council of the European Communities, which would act as a single Council for all three institutions.[13] In 1993, the Council adopted the name 'Council of the European Union', following the establishment of the European Union by the Maastricht Treaty. That treaty strengthened the Council, with the addition of more intergovernmental elements in the three pillars system. However, at the same time the Parliament and Commission had been strengthened inside the Community pillar, curtailing the ability of the Council to act independently.[11]

The Treaty of Lisbon abolished the pillar system and gave further powers to Parliament. It also merged the Council's High Representative with the Commission's foreign policy head, with this new figure chairing the foreign affairs Council rather than the rotating presidency. The European Council was declared a separate institution from the Council, also chaired by a permanent president, and the different Council configurations were mentioned in the treaties for the first time.[7]

The development of the Council has been characterised by the rise in power of the Parliament, with which the Council has had to share its legislative powers. The Parliament has often provided opposition to the Council's wishes. This has in some cases led to clashes between both bodies with the Council's system of intergovernmentalism contradicting the developing parliamentary system and supranational principles.[14]

Powers and functions

[edit]The primary purpose of the Council is to act as one of two vetoing bodies of the EU's legislative branch, the other being the European Parliament. Together they serve to amend, approve or disapprove the proposals of the European Commission, which has the sole power to propose laws.[3][5] Jointly with the Parliament, the Council holds the budgetary power of the Union and has greater control than the Parliament over the more intergovernmental areas of the EU, such as foreign policy and macroeconomic co-ordination. Finally, before the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, it formally held the executive power of the EU which it conferred upon the European Commission.[15][16] It is considered by some to be equivalent to an upper house of the EU legislature, although it is not described as such in the treaties.[17][18][19] The Council represents the executive governments of the EU's member states[2][15] and is based in the Europa building in Brussels.[20]

The Council also has an important role in the formation of the European Commission. The Council sitting in the General Affairs Council configuration, in agreement with the President-elect of the Commissission, adopts a list of candidates for the Commission proposed by the member states.[21]

Legislative procedure

[edit]

The EU's legislative authority is divided between the Council, the Parliament and the Commission. As the relationships and powers of these institutions have developed, various legislative procedures have been created for adopting laws.[15] In early times, the avis facultatif maxim was: "The Commission proposes, and the Council disposes";[22] but now the vast majority of laws are subject to the ordinary legislative procedure, which works on the principle that consent from both the Council and Parliament are required before a law may be adopted.[23]

Under this procedure, the Commission presents a proposal to Parliament and the Council. Following its first reading the Parliament may propose amendments. If the Council accepts these amendments then the legislation is approved. If it does not then it adopts a "common position" and submits that new version to the Parliament. At its second reading, if the Parliament approves the text or does not act, the text is adopted, otherwise the Parliament may propose further amendments to the Council's proposal. It may be rejected out right by an absolute majority of MEPs. If the Council still does not approve the Parliament's position, then the text is taken to a "Conciliation Committee" composed of the Council members plus an equal number of MEPs. If a Committee manages to adopt a joint text, it then has to be approved in a third reading by both the Council and Parliament or the proposal is abandoned.[24]

The few other areas that operate the special legislative procedures are justice & home affairs, budget and taxation and certain aspects of other policy areas: such as the fiscal aspects of environmental policy. In these areas, the Council or Parliament decide law alone.[25][26] The procedure used also depends upon which type of institutional act is being used. The strongest act is a regulation, an act or law which is directly applicable in its entirety. Then there are directives which bind members to certain goals which they must achieve, but they do this through their own laws and hence have room to manoeuvre in deciding upon them. A decision is an instrument which is focused at a particular person or group and is directly applicable. Institutions may also issue recommendations and opinions which are merely non-binding declarations.[27]

The Council votes in one of three ways; unanimity, simple majority, or qualified majority. In most cases, the Council votes on issues by qualified majority voting, meaning that there must be a minimum of 55% of member states agreeing (at least 15) who together represent at least 65% of the EU population.[28] A 'blocking minority' can only be formed by at least 4 member states, even if the objecting states constitute more than 35% of the population.[29]

Resolutions

[edit]Council resolutions have no legal effect. Usually the Council's intention is to set out future work foreseen in a specific policy area or to invite action by the Commission. If a resolution covers a policy area which is not entirely within an area of EU competency, the resolution will be issued as a "resolution of the Council and the representatives of the governments of the member states".[30] Examples are the Council Resolution of 26 September 1989 on the development of subcontracting in the Community[31] and the Council Resolution of 26 November 2001 on consumer credit and indebtedness.[32]

Foreign affairs

[edit]The legal instruments used by the Council for the Common Foreign and Security Policy are different from the legislative acts. Under the CFSP they consist of "common positions", "joint actions", and "common strategies". Common positions relate to defining a European foreign policy towards a particular third-country such as the promotion of human rights and democracy in Myanmar, a region such as the stabilisation efforts in the African Great Lakes, or a certain issue such as support for the International Criminal Court. A common position, once agreed, is binding on all EU states who must follow and defend the policy, which is regularly revised. A joint action refers to a co-ordinated action of the states to deploy resources to achieve an objective, for example for mine clearing or to combat the spread of small arms. Common strategies defined an objective and commits the EUs resources to that task for four years.[33]

The Council must practice unanimity when voting on foreign affairs issues because Common Foreign and Security Policy is a "sensitive" issue (according to EUR-Lex).[34] An exception to this rule exists via Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union, which stipulates circumstances in which qualified majority voting is permissible for the Council in discussing Common Foreign and Security Policy.[34][35][36] Article 31 lays out provisions regarding a passerelle clause as well as the possibilities for Member State abstentions.[35][37] Additionally, Article 31 stipulates derogation for "a decision defining a Union action or position".[35][37] In late 2023 and early 2024, unanimity voting on foreign affairs issues by the Council made headlines due to the resistance of Viktor Orbán, Prime Minister of Hungary, to passing European Union aid to Ukraine.[38][39][40] In this recent example, the Council came to a unified conclusion after discussions with the Hungarian leader;[40] previously at the end of 2023, Orbán had left the room during the Council vote on Ukraine-EU accession talks, this ensuring that the Council passed that issue without veto.[39]

Budgetary authority

[edit]The legislative branch officially holds the Union's budgetary authority. The EU's budget (which is around 155 billion euro)[41] is subject to a form of the ordinary legislative procedure with a single reading giving Parliament power over the entire budget (prior to 2009, its influence was limited to certain areas) on an equal footing with the Council. If there is a disagreement between them, it is taken to a conciliation committee as it is for legislative proposals. But if the joint conciliation text is not approved, the Parliament may adopt the budget definitively.[25] In addition to the budget, the Council coordinates the economic policy of members.[6]

Organisation

[edit]The Council's rules of procedure contain the provisions necessary for its organisation and functioning.[42]

Presidency

[edit]The Presidency of the Council is not a single post, but is held by a member state's government. Every six months the presidency rotates among the states, in an order predefined by the Council's members, allowing each state to preside over the body. From 2007, every three member states co-operate for their combined eighteen months on a common agenda, although only one formally holds the presidency for the normal six-month period. For example, the President for the second half of 2007, Portugal, was the second in a trio of states alongside Germany and Slovenia with whom Portugal had been co-operating. The Council meets in various configurations (as outlined below) so its membership changes depending upon the issue. The person chairing the Council will always be the member from the state holding the Presidency. A delegate from the following Presidency also assists the presiding member and may take over work if requested.[43][44] The exception however is the foreign affairs council, which has been chaired by the High Representative since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty.[7]

The role of the Presidency is administrative and political. On the administrative side it is responsible for procedures and organising the work of the Council during its term. This includes summoning the Council for meetings along with directing the work of COREPER and other committees and working parties. The political element is the role of successfully dealing with issues and mediating in the Council. In particular this includes setting the agenda of the council, hence giving the Presidency substantial influence in the work of the Council during its term. The Presidency also plays a major role in representing the Council within the EU and representing the EU internationally, for example at the United Nations.[44][45][46]

Configurations

[edit]Legally speaking, the Council is a single entity (this means that technically any Council configuration can adopt decisions that fall within the remit of any other Council configuration)[47] but it is in practice divided into several different council configurations (or '(con)formations'). Article 16(6) of the Treaty on European Union provides:

The Council shall meet in different configurations, the list of which shall be adopted in accordance with Article 236 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

The General Affairs Council shall ensure consistency in the work of the different Council configurations. It shall prepare and ensure the follow-up to meetings of the European Council, in liaison with the President of the European Council and the Commission.

The Foreign Affairs Council shall elaborate the Union's external action on the basis of strategic guidelines laid down by the European Council and ensure that the Union's action is consistent.

Each council configuration deals with a different functional area, for example agriculture and fisheries. In this formation, the council is composed of ministers from each state government who are responsible for this area: the agriculture and fisheries ministers. The chair of this council is held by the member from the state holding the presidency (see section above). Similarly, the Economic and Financial Affairs Council is composed of national finance ministers, and they are still one per state and the chair is held by the member coming from the presiding country. The Councils meet irregularly throughout the year except for the three major configurations (top three below) which meet once a month. As of 2020[update], there are ten formations:[48][49]

- General Affairs (GAC)

- General affairs co-ordinates the work of the Council, prepares for European Council meetings and deals with issues crossing various council formations.

- Foreign Affairs (FAC)

- Chaired by the High Representative, rather than the Presidency, it manages the CFSP, CSDP, trade and development co-operation. It sometimes meets in a defence configuration.[50]

- Economic and Financial Affairs (Ecofin)

- Composed of economics and finance ministers of the member states. It includes budgetary and eurozone matters via an informal group composed only of eurozone member ministers.[51]

- Agriculture and Fisheries (Agrifish)

- Composed of the agriculture and fisheries ministers of the member states. It considers matters concerning the Common Agricultural Policy, the Common Fisheries Policy, forestry, organic farming, food and feed safety, seeds, pesticides, and fisheries.[52]

- Justice and Home Affairs (JHA)

- This configuration brings together Justice ministers and Interior Ministers of the Member States. Includes civil protection.

- Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs (EPSCO)

- Composed of employment, social protection, consumer protection, health and equal opportunities ministers.

- Competitiveness (COMPET)

- Created in June 2002 through the merging of three previous configurations (Internal Market, Industry and Research). Depending on the items on the agenda, this formation is composed of ministers responsible for areas such as European affairs, industry, tourism and scientific research. With the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, the EU acquired competence in space matters,[53] and space policy has been attributed to the Competitiveness Council.[54]

- Transport, Telecommunications and Energy (TTE)

- Created in June 2002, through the merging of three policies under one configuration, and with a composition varying according to the specific items on its agenda. This formation meets approximately once every two months.

- Environment (ENV)

- Composed of environment ministers, who meet about four times a year.

- Education, Youth, Culture and Sport (EYC)

- Composed of education, culture, youth, communications and sport ministers, who meet around three or four times a year.[55] Includes audiovisual issues.

Complementing these, the Political and Security Committee (PSC) brings together ambassadors to monitor international situations and define policies within the CSDP, particularly in crises.[49] The European Council is similar to a configuration of the Council and operates in a similar way, but is composed of the national leaders (heads of government or state) and has its own President,[56] since 2019, Charles Michel. The body's purpose is to define the general "impetus" of the Union.[57] The European Council deals with the major issues such as the appointment of the President of the European Commission who takes part in the body's meetings.[58]

Ecofin's Eurozone component, the Euro group, is also a formal group with its own President.[51] Its European Council counterpart is the Euro summit formalized in 2011[59] and the TSCG.

Following the entry into force of a framework agreement between the EU and ESA there is a Space Council configuration—a joint and concomitant meeting of the EU Council and of the ESA Council at ministerial level dealing with the implementation of the ESP adopted by both organisations.[60][61]

Administration

[edit]The General Secretariat of the Council provides the continuous infrastructure of the Council, carrying out preparation for meetings, draft reports, translation, records, documents, agendas and assisting the presidency.[62] The Secretary General of the Council is head of the Secretariat.[63] The Secretariat is divided into eleven directorates-general, each administered by a director-general.[64]

The Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER) is a body composed of representatives from the states (ambassadors, civil servants etc.) who meet each week to prepare the work and tasks of the Council. It monitors and co-ordinates work and deals with the Parliament on co-decision legislation.[65] It is divided into two groups of the representatives (Coreper II) and their deputies (Coreper I). Agriculture is dealt with separately by the Special Committee on Agriculture (SCA). The numerous working parties submit their reports to the Council through Coreper or SCA.[49]

Governments represented in the Council

[edit]The Treaty of Lisbon mandated a change in voting system from 1 November 2014 for most cases to double majority Qualified Majority Voting, replacing the voting weights system. Decisions made by the council have to be taken by 55% of member states representing at least 65% of the EU's population.[7]

Almost all members of the Council are members of a political party at national level, and most of these are members of a European-level political party. However the Council is composed to represent the Member States rather than political parties[6] and the nature of coalition governments in a number of states means that party breakdown at different configuration of the Council vary depending on which domestic party was assigned the portfolio. However, the broad ideological alignment of the government in each state does influence the nature of the law the Council produces and the extent to which the link between domestic parties puts pressure on the members in the European Parliament to vote a certain way.

Location

[edit]By a decision of the European Council at Edinburgh in December 1992, the Council has its seat in Brussels but in April, June, and October, it holds its meetings in Luxembourg City.[66] Between 1952 and 1967, the ECSC Council held its Luxembourg City meetings in the Cercle Municipal on Place d'Armes. Its secretariat moved on numerous occasions but between 1955 and 1967 it was housed in the Verlorenkost district of the city. In 1957, with the creation of two new Communities with their own Councils, discretion on location was given to the current Presidency. In practice this was to be in the Château of Val-Duchesse until the autumn of 1958, at which point it moved to 2 Rue Ravensteinstraat in Brussels.[67]

The 1965 agreement (finalised by the Edinburgh agreement and annexed to the treaties) on the location of the newly merged institutions, the Council was to be in Brussels but would meet in Luxembourg City during April, June, and October. The ECSC secretariat moved from Luxembourg City to the merged body Council secretariat in the Ravenstein building of Brussels. In 1971 the Council and its secretariat moved into the Charlemagne building, next to the Commission's Berlaymont, but the Council rapidly ran out of space and administrative branch of the Secretariat moved to a building at 76 Rue Joseph II/Jozef II-straat and during the 1980s the language divisions moved out into the Nerviens, Frère Orban, and Guimard buildings.[67]

In 1995, the Council moved into the Justus Lipsius building, across the road from Charlemagne.[clarification needed] However, its staff was still increasing, so it continued to rent the Frère Orban building to house the Finnish and Swedish language divisions. Staff continued to increase and the Council rented, in addition to owning Justus Lipsius, the Kortenberg, Froissart, Espace Rolin, and Woluwe Heights buildings. Since acquiring the Lex building in 2008, the three aforementioned buildings are no longer in use by the Council services.[citation needed]

When the Council is meeting in Luxembourg City, it meets in the Kirchberg Conference Centre,[67] and its offices are based at the European Centre on the plateau du Kirchberg.[49] The Council has also met occasionally in Strasbourg, in various other cities, and also outside the Union: for example in 1974 when it met in Tokyo and Washington, D. C. while trade and energy talks were taking place. Under the Council's present rules of procedures the Council can, in extraordinary circumstances, hold one of its meetings outside Brussels and Luxembourg.[67]

From 2017, both the Council of the European Union and the European Council adopted the purpose-built Europa building as their official headquarters, although they continue to utilise the facilities afforded by the adjacent Justus Lipsius building. The focal point of the new building, the distinctive multi-storey "lantern" shaped structure in which the main meeting room is located, is utilised in both EU institutions' new official logos.[20][68]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In the treaties and legislative documents, the institution is referred to simply as "the Council". The Latin word consilium is also found as a "language-neutral" name in signage, website names, etc.

References

[edit]- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "EUR-Lex - C:2016:202:TOC - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Legislative powers". European Parliament. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ "Parliament's legislative initiative" (PDF). Library of the European Parliament. 24 October 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Planning and proposing law". European Commission. 20 April 2019. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Council of the European Union". Council of the European Union. 16 June 2016. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d "The Union's institutions: The Council of Ministers". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 24 June 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2007.

- ^ "The General Secretariat of the Council". European Council Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ "Secretary-General". European Council Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ "Directors-General". European Council Council of the European Union.

- ^ a b "Council of the European Union". European NAvigator. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^ Ludlow, N (2006). "De-commissioning the Empty Chair Crisis : the Community institutions and the crisis of 1965–6" (PDF). London School of Economics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ^ EUR-Lex, Treaty of Brussels (Merger Treaty) Archived 1 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, updated 21 March 2018, accessed 29 January 2021

- ^ Hoskyns, Catherine; Michael Newman (2000). Democratizing the European Union: Issues for the twenty-first Century (Perspectives on Democratization. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5666-6.

- ^ a b c "Legislative power". European Parliament. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- ^ "Treaty on the European Union (Nice consolidated version)" (PDF). Europa (web portal). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^ A. Börzel, Tanja; A. Cichowski, Rachel (4 September 2003). The State of the European Union, 6:Law, politics, and society. Oxford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0199257409.

- ^ Bicameralism. Cambridge University Press. 13 June 1997. p. 58. ISBN 9780521589727.

- ^ Taub, Amanda (29 June 2016). "The E.U. Is Democratic. It Just Doesn't Feel That Way". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ a b "EUROPA : Home of the European Council and the Council of the EU - Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ "How the Commission is appointed". European Commission. Directorate-General for Communication. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ "News - Archives - Highlights - Codecision and other procedures". www.europarl.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ "The Codecision Procedure". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- ^ "Codecision procedure". European Parliament. Archived from the original on 16 February 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- ^ a b "Explaining the Treaty of Lisbon". Europa website. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ "Decision-making in the European Union". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ "Community legal instruments". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- ^ "Voting system". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ^ "Qualified Majority". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ General Secretariat of the Council, Council conclusions and resolutions, updated 3 December 2020, accessed 29 January 2021

- ^ EUR-Lex, Council Resolution of 26 September 1989 on the development of subcontracting in the Community, 89/C 254/01, accessed 29 January 2021

- ^ EUR-Lex, Council Resolution of 26 November 2001 on consumer credit and indebtedness, 2001/C 364/01, accessed 29 January 2021

- ^ "Joint actions, common positions and common strategies". French Foreign Ministry. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ a b "Unanimity - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2 October 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Consolidated version of the Treaty on European Union TITLE V - GENERAL PROVISIONS ON THE UNION'S EXTERNAL ACTION AND SPECIFIC PROVISIONS ON THE COMMON FOREIGN AND SECURITY POLICY CHAPTER 2 - SPECIFIC PROVISIONS ON THE COMMON FOREIGN AND SECURITY POLICY SECTION 1 - COMMON PROVISIONS Article 31 (ex Article 23 TEU), 7 June 2016, archived from the original on 2 October 2024, retrieved 13 May 2024

- ^ Ramopoulos, Thomas (May 2019). "Article 31 TEU". In Kellerbauer, Manuel; Klamert, Marcus; Tomkin, Jonathan (eds.). The EU Treaties and the Charter of Fundamental Rights: A Commentary (online ed.). New York: Oxford Academic. pp. 242–247. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198759393.003.41. ISBN 978-0-19-879456-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b "For the EU, moving from unanimity to qualified majority is a Catch-22". euronews. 13 June 2023. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Stevis-Gridneff, Matina; Erlanger, Steven (14 December 2023). "Hungary Blocks Ukraine Aid After E.U. Opens Door to Membership". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 October 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Toilet diplomacy: How many bathroom breaks can the EU force Viktor Orbán to take?". POLITICO. 1 February 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ a b "EU approves €50B Ukraine aid as Viktor Orbán folds". POLITICO. 1 February 2024. Archived from the original on 2 October 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Multiannual Financial Framework-European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ "EUR-Lex - o10003 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2 October 2024. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "What is the Presidency?". 2007 German Presidency website. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^ a b "The Presidency". 2007 Portuguese Presidency website. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ "The presidency in general". 2007 Finnish Presidency website. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ "Council Decision of 15 September 2006 adopting the Council's Rules of Procedure" (PDF). Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ^ "The decision-making process in the Council - Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ^ "Council configurations". Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^ a b c d Information handbook of the Council of the European Union. Brussels: Office of Official Publications of the European Communities. 2007. ISBN 978-92-824-2203-8.

- ^ "Report from the conference on crisis management, French presidency, 2008". Eu2008.fr. 31 October 2008. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ a b "The CER guide to the EU's constitutional treaty" (PDF). Centre for European Reform. July 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^ "Consilium - Agriculture and Fisheries". Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Article 4 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU". eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 5 September 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "Competitiveness Council configuration (COMPET)". Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "Education, Youth, Culture and Sport Council configuration (EYCS)". Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "European Council – The institution". Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "European Council". Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^ "European Commission". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ^ "26 October 2011 Euro summit conclusions" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- ^ "ESA PR: N° 21-2007: Europe's Space Policy becomes a reality today". Esa.int. 22 May 2007. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "Framework Agreement between the European Community and the European Space Agency". Council of the European Union. Retrieved 22 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "General Secretariat of the Council". Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^ "Secretary-General". European Council Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ "Directors-General". European Council Council of the European Union.

- ^ "Glossary". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^ European Council (12 December 1992). "European Council in Edinburgh: 11–12 December 1992, Annex 6 to Part A" (PDF). European Parliament. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Seat of the Council of the European Union". European NAvigator. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "New HQ, new logo". POLITICO. 15 January 2014. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

External links

[edit]- Official Council website – Europa

- Access to documents of the EU Council on EUR-Lex

- Council of the European Union Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine – European NAvigator

- Archival material concerning the Council of the European Union can be consulted at the Historical Archives of the European Union in Florence