Draft:Waukeshaaspis

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Fossiladder13 (talk | contribs) 0 seconds ago. (Update) |

| Waukeshaaspis Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil specimen of W. eatonae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | †Trilobita |

| Order: | †Phacopida |

| Family: | †Dalmanitidae |

| Genus: | †Waukeshaaspis Randolfe & Gass, 2024 |

| Species: | †W. eatonae

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Waukeshaaspis eatonae Randolfe & Gass, 2024

| |

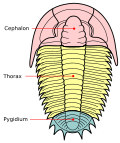

Waukeshaaspis is an extinct genus of trilobite (a diverse group of marine arthropods) known from the lower Silurian aged Waukesha Biota. A single species is currently known, Waukeshaaspis eatonae, which is known from strata belonging to the Telychian aged Brandon Bridge Formation in Wisconsin. Originally discovered alongside the Waukesha Biota in 1985, this genus wouldn't be properly described until 2024. Currently, this genus is placed within the Dalmanitidae family, within the larger Phacopida, which lasted from the Lower Ordovician to the Upper Devonian.

This genus is rather unique, as it is the only common trilobite found within the Waukesha Biota, and is usually preserved in a more complete state compared to other contemporary genera. Its abundance is also notable, with around 200 or so specimens having been recorded, making it one of the most abundant organisms at the site. This arthropod is so common, that entire planes of rock have been found with dozens of preserved exoskeletons. Its sheer abundance suggests that this trilobite was well adapted to the conditions present in the region. This contrasts with the known taphonomic bias that the Waukesha biota has, where hard shelled organisms are either poorly preserved, or absent entirely. Unlike other members of the dalmanitid family, the pygidium (posterior section) of this genus lacks a terminal spine, instead possessing an embayment which may have helped with respiration when the arthropod was enrolled.

Background

[edit]The Brandon Bridge Formation is a geologic formation within the state of Wisconsin that dates to the Lower Silurian (more specifically the Telychian and Sheinwoodian stages).[1] Within the formation exists the smaller Waukesha Biota, a Konservat-Lagerstätten fossil site known for its exceptional preservation of soft-bodied and lightly sclerotized organisms that are not normally found in Silurian strata.[2] The biota itself is found within a 12 cm (4.7 in) layer of thinly-laminated, fine-grained, shallow marine sediments consisting of mudstone and dolomite deposited within a sedimentary trap at the end of an erosional scarp over the eroded dolomites of the Schoolcraft and Burnt Bluff Formations.[1] The site itself is known from two quarries; one in Waukesha county, and the other in the city of Franklin, in Milwaukee County.[2] The two faunas are almost identical to one another, with the exception being that the Franklin quarry lacks any fossils of trilobites.[2][3] A unique trait of the biota is its taphonomy, being that the majority of hard-shelled organisms (which are normally found in Silurian strata), are poorly preserved, or entirely absent.[2] With the exceptions to this being the various trilobites and conulariids (a group of cnidarians with pyramidal theca) from the site.[2] The exceptional preservation of non-biomineralized and lightly sclerotized remains of the Waukesha Biota is generally attributed to a combination of favorable conditions, including the transportation of organisms to a sediment trap that helped to protect from scavengers, and promoted the build up of organic films that coated the surfaces of the dead organisms, which inhibited decay, sometimes enhanced by promoting precipitation of a thin phosphatic coating, which is observed on many of the fossils.[4][5] However, some of the fossils are also coated with other materials, including pyrite and calcium carbonate.[2][3]

Discovery and Naming

[edit]Waukeshaaspis was first discovered alongside the Waukesha Biota in 1985, due to quarrying activity conducted by Waukesha Lime And Stone Company, which revealed the Lagerstätten.[6][1] Fossils of this genus are only known from the Waukesha quarry, along with the entirety of the other trilobite fossils from the locality.[2] Before it was named, Waukeshaaspis was recognized as one of the most common organisms within the Waukesha Biota, only behind several unnamed members of the Leperditicopida (a group of bivalved arthropods sometimes associated with the ostracods).[1][3] It was also recognized as a new species due to the unique differences between it and other dalmanitids.[7] Despite its recognition, it would take multiple decades before this genus would receive a proper description, which was published by Randolfe & Gass, 2024.[3] The holotype specimen of Waukeshaaspis, UWGM 7447, and most of the known recorded fossils are currently housed within the UW–Madison Geology Museum, along with the majority of the Waukesha fossils.[3][6][5][2]

This arthropods genus name, Waukeshaaspis, is derived from the city of Waukesha, and the Greek word aspís, meaning "round shield".[3][8] The specific name, eatonae, is in honour of Carrie Eaton, who is the curator of the UWGM, and has helped to catalogue the Waukesha fossils.[3]

Description

[edit]

Waukeshaaspis was a modest sized trilobite, with a average length of around 60 mm (6 cm) long, with sizes going down to at least 9 mm (0.9 cm).[3] The cephalon of the trilobite was semi-circular, and possessed very long genal spines that extended down to the beginning of the pygidium.[3] The cephalon also posessed a facial suture that was anterior to the trilobites glabellar region, which would have assisted during ecdysis (or molting), as the librigenal area of the cephalon would split along the suture, exposing the other areas of the trilobites head.[9][3] The glabella was roughly the same size, in terms of length and width, and would housed the trilobites crop.[3] The trilobites pair of eyes sat on the posterior margin of the cephalon, and were composed of around 32 files, which bore eight distinct lenses.[3] The eyes themselves were notably large, and sat on an elevated area of the preocular region of the cephalon.[3] The thorax was composed of around 11 distinct segments, which gradually increased in both length and width before gradually experiencing a decrease in width.[3] The animals pygidium was roughly triangular in shape, and possessed a distinct embayment towards the terminal end, but lacked a terminal spine as seen in most other dalmanitids.[3] The pygidium also possessed around 10 pairs of axial segments and pleurae, but also a smaller, more elongated piece just in front of the embayment.[3] The embayment itself sat towards the posterior-medial area of pygidium, and possessed a gradual curve and narrow shape.[3] Despite the abundance of both dorsal and ventral oriented specimens, no fossils are known which preserve the various appendages, including the antennae, gills, and biramous limbs.[3] The animals hypostome (a hard mouthpart which sat ventral side of the cephalon) is also unknown.[3][10] Despite this, several fossils of Waukeshaaspis, including UWGM 7460 and UWGM 7461, have been found with persevered gastrointestinal tracts.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Mikulic, Donald G.; Briggs, D.E.G.; Kluessendorf, Joanne (1985). "A new exceptionally preserved biota from the Lower Silurian of Wisconsin, U.S.A." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 311 (1148): 75–85. Bibcode:1985RSPTB.311...75M. doi:10.1098/rstb.1985.0140. JSTOR 2396972.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wendruff, Andrew J.; Babcock, Loren E.; Kluessendorf, Joanne; Mikulic, Donald G. (2020). "Paleobiology and Taphonomy of exceptionally preserved organisms from the Waukesha Biota (Silurian), Wisconsin, USA". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 546: 109631. Bibcode:2020PPP...54609631W. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109631. S2CID 212824469.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Randolfe, E. A.; Gass, K. C. (2024). "Waukeshaaspis eatonae n. gen. n. sp.: a specialized dalmanitid (Trilobita) from the Telychian of southeastern Wisconsin". Journal of Paleontology: 1–9. doi:10.1017/jpa.2024.32.

- ^ Wendruff, Andrew J.; Babcock, Loren E.; Wirkner, Christian S.; Kluessendorf, Joanne; Mikulic, Donald G. (2020). "A Silurian ancestral scorpion with fossilised internal anatomy illustrating a pathway to arachnid terrestrialisation". Scientific Reports. 10 (14): 14. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10...14W. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-56010-z. PMC 6965631. PMID 31949185.

- ^ a b Jones, Wade T.; Feldman, Rodney M.; Schweitzer, Carrie E. (2015). "Ceratiocaris from the Silurian Waukesha Biota, Wisconsin". Journal of Paleontology. 89 (6): 1007–1021. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.22. S2CID 131127241.

- ^ a b Pulsipher, M. A.; Anderson, E. P.; Wright, L. S.; Kluessendorf, J.; Mikulic, D. G.; Schiffbauer, J. D. (2022). "Description of Acheronauta gen. nov., a possible mandibulate from the Silurian Waukesha Lagerstätte, Wisconsin, USA". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 20 (1). 2109216. doi:10.1080/14772019.2022.2109216. S2CID 252839113.

- ^ Gass, Kenneth C.; Braddy, Simon J. (2023). "The Waukesha Biota: a wonderful window into early Silurian life". Geology Today. 39 (5): 169–176. doi:10.1111/gto.12447. ISSN 0266-6979.

- ^ "Definition of ASPIS". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2024-11-17.

- ^ Riccardo Levi-Setti (1995), Trilobites, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-47452-6

- ^ Fortey, R. A.; Owens, R. M. (1999), "Feeding habits in trilobites", Palaeontology, 42 (3): 429–65, Bibcode:1999Palgy..42..429F, doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00080, S2CID 129576413