Draft:God manifested in the flesh

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 7 weeks or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 1,347 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

"God manifested in the flesh" (Greek: θεός ἐφανερώθη ἐν σαρκί) is a textual variant found in 1 Timothy 3:16 in later Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. It likely originated in the 3rd century, either as a scribal error influenced by orthographic conventions or as an intentional theological clarification to emphasize Christ's divinity. This reading was incorporated into the Textus Receptus in the 16th century and became a standard in many New Testament editions for centuries.

From the 18th century onward, this variant became the subject of dogmatic disputes. Textual critics questioned its authenticity, risking accusations of supporting Unitarianism. However, since the late 19th century, the variant "who was manifested in the flesh" (ὅς ἐφανερώθη ἐν σαρκί), supported by earlier manuscripts and translations, has been considered authentic. The defense of the variant regarded as affirming Christ's divinity, however, continues to be carried out by supporters of the rejected Textus Receptus.

Antiquity and early Middle Ages

[edit]

The Codex Sinaiticus (4th century), the oldest Greek manuscript of the New Testament containing the text of 1 Timothy,[1] preserves the variant ὅς ("who"), giving the phrase in 1 Timothy 3:16 the meaning "who was manifested in the flesh".[2] This reading is supported by the 5th-century manuscripts Codex Alexandrinus,[3] Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, as well as later manuscripts such as Codex Augiensis, Codex Boernerianus, and others (e.g., Minuscules 17, 33, 365, 442, 1175, 2127, and the lectionary 599).[2][4][5] It is also affirmed by ancient translations, including the Syriac, Gothic, Ethiopian, and Coptic versions.[6] Church Fathers such as Origen, Epiphanius of Salamis, Jerome, Theodoret, Cyril of Alexandria, and Liberatus of Carthage used this variant.[2]

The Codex Claromontanus transmits the variant ὅ ("which"), relating it to μυστηριον ("mystery") from the preceding phrase.[a] The resulting meaning is "great is the mystery of godliness, which was manifested in the flesh".[7] This variant is supported by Old Latin translations, the Vulgate, and Latin Church Fathers such as Ambrose, Pelagius, and Augustine of Hippo.[6] This reading indirectly supports ὅς as the original variant,[8] as it likely arose from an intentional alteration for grammatical consistency, disregarding the context that points clearly to Christ.[9] This reading is characteristic of the Western text-type.[10]

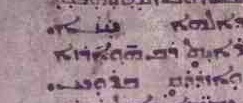

The Peshitta uses a relative pronoun![]() that can correspond to either ὅς or ὅ in Greek.[11]

that can correspond to either ὅς or ὅ in Greek.[11]

Uncial 061 contains the variant ω ("to whom"), rendering the phrase "to whom was manifested in the flesh".[6]

The ὅς variant is widely regarded as original, based on its attestation in early manuscripts and translations. Scholars of Christological hymns note that early confessions of faith often begin with a relative pronoun,[9] as seen in Philippians 2:6 and Colossians 1:15.[12]

θεός variant

[edit]

One of the oldest Greek manuscripts using the variant θεός ἐφανερώθη ("God was manifested") is the Codex Athous Lavrensis, dated to the late 9th or early 10th century.[8] This variant is supported by most later manuscripts. Important examples include the Codex Mosquensis I, Codex Angelicus, Codex Porphyrianus, Uncial 075, Uncial 0150, and others such as Minuscules 6, 81, 104, 181, 326, 330, 436, 451, 614, 629, 630, 1241, 1505, 1739, 1877, 1881, 1962, 1984, 1985, 2492, 2495, Byzantine text-type manuscripts, and lectionaries.[4][6]

Among the Church Fathers, this variant appears from the 4th century onwards,[8][13] used by figures such as Gregory of Nyssa, Didymus the Blind, John Chrysostom, Theodoret, Euthalius, and later theologians.[8]

The Codex Sinaiticus was corrected by a 12th-century scribe (corrector e).[8] Similarly, corrections aligning the texts of the Codex Alexandrinus, Ephraemi Rescriptus, and the Codex Clermont with the normative theological text were carried out in other manuscripts.[b][8] These adjustments emphasized the doctrine of divine incarnation.[9]

The variant θεός ἐφανερώθη could have arisen accidentally if ΟΣ was misread as ΘΣ (an abbreviation for θεός).[14] Alternatively, it may have been a deliberate modification to provide a noun for the six subsequent verbs, motivated by orthographic considerations. According to Bruce M. Metzger, there is also a slight possibility that the change was dogmatically inspired.[8][13]

Bart D. Ehrman argues that the variant likely originated no later than the 3rd century, with anti-adoptionist motivations aimed at emphasizing Christ's divinity.[9]

Printed text

[edit]

The variant "God manifested" was adopted in the first printed editions of the Greek New Testament (Textus Receptus) and, through them, entered modern translations of the New Testament.[15] Ludolf Küster, in his second and expanded edition of John Mill's Novum Testamentum, used the variant consistent with the Textus Receptus but noted in a footnote the manuscripts and Church Fathers supporting the variant ὅς ἐφανερώθη.[16]

Isaac Newton wrote An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture, rejecting two Textus Receptus variants: the Johannine Comma and θεός ἐφανερώθη from 1 Timothy 3:16. Newton, fearing accusations of unitarianism, refrained from publishing his work, instead sending the manuscript to John Locke in 1690.[17] He suggested translating it into French and publishing it in France. Locke passed it to Jean Le Clerc, who recommended Newton review Richard Simon's Histoire critique du texte du Nouveau Testament. Newton revised his work, and Le Clerc prepared a Latin translation but did not publish it at Newton's request. The work was only published posthumously in 1754[17][18] and its original manuscript in 1785.[19]

Johann Jakob Wettstein, a theologian from Basel, observed during his study of the Codex Alexandrinus that the ligature above the letters theta and sigma was added with different ink and by another hand. Additionally, the horizontal line inside theta was not part of the letter but a bleed-through from the other side of the parchment. Thus, Christ was not called God in this manuscript.[20] In 1730, Wettstein published Prolegomena ad Novi Testamenti Graeci, supporting the variant ὅς ἐφανερώθη and questioning the authenticity of the Johannine Comma and Acts 20:28.[21] He derived this variant from the Codex Alexandrinus and Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus. Shortly after the publication of Prolegomena, he was accused of Socinianism, expelled from the clergy, and relocated to Amsterdam.[22] There, between 1751 and 1752, he published his version of the New Testament text.[23]

Supporters of the Textus Receptus included Daniel Whitby, Franz Anton Knittel, and others. Carl Gottfried Woide, in his facsimile of the Codex Alexandrinus, used the variant ΘΣ and disputed Wettstein's claim that the original text had ΟΣ.[24] Critics of the Textus Receptus, such as Johann Albrecht Bengel, Johann Jakob Griesbach, Karl Lachmann, Constantin von Tischendorf, Samuel Prideaux Tregelles, and John Wordsworth, rejected the variant ΘΣ.[11]

Brooke Foss Westcott and F. J. A. Hort, in their The New Testament in the Original Greek, endorsed the variant confirmed by ancient manuscripts.[10][25] Since then, most translations have adopted "who was manifested in the flesh".[10]

Dean Burgon, in Revision Revised, devoted 77 pages to defending the Textus Receptus variant.[26] He doubted the Codex Alexandrinus and Ephraemi Rescriptus supported ὅς, arguing that heavy consultation of the Alexandrinus page after 1770 reduced its readability. He cited the Georgian and Church Slavonic translations and Church Fathers using the variant.[27]

Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener cautiously favored the θεός variant but hesitated to dismiss it as a scribal error.[27] He acknowledged the Codex Alexandrinus and Ephraemi Rescriptus as witnesses to ὅς but with reservations.[5]

Eberhard Nestle highlighted a similar situation in Joshua 2:11 in the Septuagint. The Codex Vaticanus and Ambrosianus use κυριος ο θεος υμων ος εν ουρανω ανω, while the Codex Alexandrinus has κυριος ο θεος υμων θεος εν ουρανω ανω.[28]

Today, fundamentalist Protestants in the Burgon Society and the King James Only movement defend the Textus Receptus variant.[29] They claim that the critical apparatus of modern editions of the Greek New Testament has been falsified, asserting that the corrector of the Codex Sinaiticus lived not in the 12th century but in the 4th century, with corrections made before the manuscript left the scriptorium. They also argue that alleged falsifications by modern textual critics extend to manuscripts A, C, F, and G.[30] Proponents maintain that the Textus Receptus variant is grammatically superior and that this verse is one of the few biblical texts directly supporting Christ's divinity, with other verses doing so only indirectly.[31]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In Greek, μυστηριον is of the neuter gender.

- ^ The correctors of the Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus and the Codex of Clermont are dated to approximately the 9th century (Aland (1995, p. 108)).

References

[edit]- ^ Nestle (2012, p. 65)

- ^ a b c Metzger (2001, p. 573)

- ^ "Codex Alexandrinus, 1 Timothy 3:16". www.bible-researcher.com. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ a b Nestle (2012, p. 638)

- ^ a b Scrivener (1894, p. 390)

- ^ a b c d Aland, Barbara, ed. (1993). The Greek New Testament (4 ed.). Stuttgart: United Bible Societies. p. 718. ISBN 978-3-438-05110-3.

- ^ Metzger (2001, pp. 573–574)

- ^ a b c d e f g Metzger (2001, p. 574)

- ^ a b c d Ehrman (1993, p. 78)

- ^ a b c Westcott, B. F.; Hort, F. J. A. (1882). Introduction to the New Testament in the Original Greek. pp. 132–134.

- ^ a b Scrivener (1894, p. 392)

- ^ Ehrman (1993, p. 111)

- ^ a b Omanson (2006, p. 438)

- ^ Aland (1995, p. 283)

- ^ Omanson (2006, p. 437)

- ^ Mill, John; Küster, Ludolf (1723). Novum Testamentum graecum (in Latin). Sumtibus Filii J. Friderici Gleditschii. pp. 491–492.

- ^ a b Attig, John C. (2010). "John Locke Manuscripts – Chronological Listing: 1690". www.libraries.psu.edu. Archived from the original on 2004-08-28.

- ^ Newton, Sir Isaac (1841). An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture: In a Letter to a Friend. J. Green.

- ^ Attig, John C. "John Locke Bibliography — Chapter 5, Religion, 1751-1900". www.libraries.psu.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-05-27.

- ^ Ehrman (2009, pp. 134–135)

- ^ Ehrman (2009, p. 136)

- ^ Scrivener (1894, p. 213)

- ^ Ehrman (2009, p. 137)

- ^ Horne, Thomas Hartwell; Tregelles, Samuel Prideaux; Davidson, Samuel (1856). An Introduction to the critical study and knowledge of the Holy Scriptures. London. p. 156.

- ^ Westcott, Brooke Foss; Hort, Fenton John Anthony (2007). The Greek New Testament: with comparative apparatus showing variations from the Nestle-Aland and Robinson-Pierpont editions. Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson Publ. p. 558. ISBN 978-1-56563-674-3.

- ^ Burgon, John William (1883). The Revision Revised. London: John Murray. pp. 424–501.

- ^ a b Scrivener (1894, p. 395)

- ^ Nestle, Eberhard (1901). Introduction to the textual criticism of the Greek New Testament. New York: Williams and Norgate. p. 318.

- ^ Jones, Floyd (1998). Ripped Out The Bible (PDF). KingsWord Press. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-03.

- ^ Jones, Scott (2001). False Citations: 1 Timothy 3:16 Examined. Lamb Lion Net. Archived from the original on 2014-12-21.

- ^ Waite, D. A. (2004). Defending the King James Bible. ISBN 978-1568480121.

Bibliography

[edit]- Nestle, Eberhard et Erwin (2012). Aland, Barbara; Karavidopoulos, Johannes; Martini, Maria; Metzger, Bruce M. (eds.). Novum Testamentum Graece [The New Testament in Greek] (in Koine Greek) (28 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-438-05140-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Metzger, Bruce M. (2001). A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. ISBN 3-438-06010-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose (1894). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament (4 ed.). London: George Bell & Sons.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Ehrman, Bart D. (1993). The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510279-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Ehrman, Bart D. (2009). Przeinaczanie Jezusa [Distorting Jesus] (in Polish). Translated by Chowaniec, Mieszko. Warsaw: CIS. ISBN 978-83-85458-27-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Omanson, Roger L. (2006). A Textual Guide to the Greek New Testament. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. ISBN 3-438-06044-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Aland, K. (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)