Draft:Causes of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Drsmartypants(Smarty M.D) (talk | contribs) 3 seconds ago. (Update) |

On May 15th 1948, one day after the Israeli declaraction of indepedence, the Arab League - a coalition of Arab countries including Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Iraq - invaded Israel, beginning the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. This war was a continuation and escalation of the civil war in Palestine, the wider conflict being known as the 1948 Palestine War. The decision of the Arab League to invade was not taken lighty, as Arab leaders had previously rejected an invasion plan. Instead, concerns over Zionist expansionism, massacres commited in Palestine by Zionist forces, the rejection of UN and US proposed peace deals during the civil war phase by the Jewish Agency as well as public opinion at home ultimately drove the Arabs to war. In public Arab leaders stated that a unitary state would be the only solution and that their army would destroy Israel. Behind closed doors however, the Arabs understood that partition would be the most likely solution to the conflict and that their armies were not strong enough to destroy Israel.

Overview Individuals Involved

[edit]- David Ben Gurion : First Prime Minister of Israel and president of the Jewish Agency Executive

- Chaim Weizmann : First President of Israel and president of the World Zionst Organization

- Eliyahu Sasson : Head of the Arab Department of the Jewish Agency, member of the Transfer Committee

- Ezra Danin : Head of the Arab section of the Shai, the intellegence of the Haganah, another member of the Transfer Commitee

- King Farouk : King of Egypt

- Ali Maher : Prime Minister of Egypt (1936, 1939-1940)

- Ibrahim Abdel Hady Pasha : Prime Minister of Egypt (1948-1949) and chief of the Royal cabinent in 1948

- Mahmoud El Nokrashy Pasha : Prime Minister of Egypt (1946 - 1948)

Timeline

[edit]

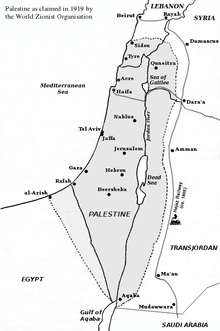

Zionists and Partition

[edit]In 1917, the British publically support a 'national home for the Jewish people" "in Palestine" in what is now known as the Balfour Declaration, in what was seen as a victory for Zionists. The declaration only referred to the Palestinians as 'Non-Jewish Communities', despite being around 90% of the population. Crucially, the terms "national home" and "in Palestine" were vague, as they did not necessarily imply a Jewish state in all of Palestine. In 1919, the Zionist Organization submitted a memorandum where they defined their terrirotial goals as all of Palestine, around 18,000 square km east of the Jordan River, and 45,000 square km of 'northern Galilee' - referring the land including the Golan Heights and what is now Lebanese territory south of the Litani River up to Sidon. They also proposed taking Egyptian territory up to El-Arish, as Herzl had previously wished[1], but left it up for further talks.[2] When the League of Nations approved the creation of Trans-Jordan as seperate from the Mandate of Palestine, Zionists were opposed to what they viewed as 'partition'. The British at this time approved of a Jewish state only when a Jewish majority was reached. Thus, Arab Palestinian self determination could only exist to the extent that they could resist Jewish immigration to Palestine.

By 1936, the Jewish population was 400,000 - around half of the Arab population.[3] In the middle of the 1930's, a massive rebellion and strike in Palestine shook the Arab world. This was the first large scale rebellion by local Arabs in a decade since the post-war revolts of the 1920's. Their demands were

- total end of Jewish immigration into Palestine

- banning of all sales of Arab land to Jews

- An indepedent Palestine and the ending of the Mandate

In a speech to the Jewish Agency, David Ben-Gurion announced that:

Peace for us is a means and not an end. The goal is realisation of Zionism, full and complete . . .only after complete disillusion on the part of the Arabs, despair will come not only from failure of the riots and the attempted rebellion, but despair which will follow our growth in the country, will it be possible for the Arabs to accept a Hebrew Palestine.[4]

One major contention was putting limits on Jewish immigration, which Ben-Gurion found unacceptable. In 1936, Musa Alami met with Jewish leaders to negotiate terms, planning for Jewish immigration at 30 thousand a year for ten years, a limit on Jewish land purchases and a Legastive Council. In London, Ben-Gurion rejected this deal, arguing that any immigration limit below the 1935 level was unacceptable. These talks fell through; the Zionists sabotaged negotiations by leaking them to the public.[5] Ben Gurion took one step further by rejecting any immigration plan that prevented an eventual Jewish majority.

The rebellion, which quickly spread all throughout Palestine despite brutal British reprisals, forcing the British to publish the Peel Commission, for the first time admitting that the Mandate was unworkable. The report divided the terroritory as:

- A Jewish state along the coast, the northern valleys, and the Galilee of around 5,000 square km.

- The rest of Palestine to be annexed by Trans-Jordan, with no plans for an independent Palestinian state

- A British mandate of a number of cities from Jaffa to Jerusalem

- Transfer of land and population between the two states.[6]

Despite being their first offer for a explicit Jewish state, the Jewish Agency was divided on whether or not to accept the report, since it only included 10% of their 1919 demands.[7] Ben Gurion lead the wing in favor of the plan, not as a permament solution, but as a stepping stone for their fulfillment of their total aspirations. In his view, the plan was

“not the lesser of evils but a political conquest and historical opportunity, unprecedented since the destruction of the Temple. I see in the realization of this plan practically the decisive stage in the beginning of full redemption and the most powerful lever for the gradual conquest of all of Palestine.”

Instead of parition as a permanent comprimse, Ben-Geruion believed that “after the formation of a large army in the wake of the establishment of the state, we will abolish partition and expand to the whole of Palestine".[8] At the meeting of the Zionist Congress in the August of 1937, everyone in the Zionist movement accepted that they had a right to settle on both sides of the Jordan river, while a majority allowed for further negotiations of partition.

Palestine and the Arab World (1936-1944)

[edit]The 1936-1939 rebellion in Palestine forced the nearby Arab states to adopt a foreign policy for Palestine. Palestine's largest neighbour, Egypt, had previously fought Herzl to prevent a Jewish state in Sinai. While the Muslim Brotherhood, a conservative Sunni Muslim organization founded in 1928, organized funds and men for the rebellion, governments in Cairo tended to be non-involved.[9] Instead, the government tried to moderate public sentiment at home, while raising the issue of Palestine to the UK.[10] In fact, one of the first examples of a collective Arab policy on Palestine was their attempt to stop the general strike.[11]

In 1938, two indivdials entered negotiations, Nuri Said from Iraq and Abdul Shahbandar from Syria. Their plans were for an Arab confederation, with an Arab government in all of Palestine with equal rights for a Jewish minority, and opening all neighboring countries for Jewish immigration. However, Shahbandar wanted a Greater Syria - Syria plus Palestine and Jordan - whle Said wanted a Greater Iraq. Nuri met with four leaders in the Arab Higher Commitee, including Jamal Husseini and Amin al Husseini, imploring them to step the rebellion and allow himself and Shahbandar to negotiate in London before the Woodhead Commission, with hope that British support for partition was wavering. The Mufti refused to the end the rebellion, and later refused to accept the 1939 White Papter and "would not agree to one more Jew entering Palestine."[12]

Egypt, under the premiership of Mohammed Mahmoud, played a large role in organizing the Arab side at the St James Conference. Ali Maher, representing Egypt, gave a speech where he said that he "appreciated and respected the Zionist ideal" but that they should "recognize realities, and particularly the fact of the existing inhabitants of Palestine", imploring them to accept either an end or limit for Jewish immigration to Palestine.[13][14] During the Conference, the Arabs rejected British offers due to their demands for a federal, rather than united, Palestine, as well as the fact that Britian refused to guarentee an independent Palestine within ten years. Egypt lead a moderating role, supporting a Palestinian state with Jewish autonomy.[15] Despite being disappointed in the 1939 White Paper, Egypt and Iraq pressured Palestinian officials against rejecting it. The White Paper called for:

- A Jewish national home within an indepedent Palestinian state within ten years, rejecting turning Palestine into a Jewish state

- Limiting Jewish immigration at 75,000 for five years with any further immigration being determined by the Arabs

- Jewish restriction on buying land[16]

Of all the delegates at the meetings, it was the Arab states that were most influential; the serious negotiations were carried out between Britain and the Arab state after Britain was assured that the Zionists and Palestinians would not rebel.[16] While the Mufti rejected the plan, Musa Alami and Jamal Husseini accepted its terms and signed a copy in the presense of Nuri Said.[17]

Formation of the Arab League (1944-1946)

[edit]The UK submits Palestine to the UN (goes over the events in UN until Septemeber 1947 and the situation in Egypt and Syria)

[edit]Arab reaction to Partition

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "This Week in History: Herzl's Sinai alternative". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 2013-07-20. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- ^ Galnoor 2009, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Cohen 1977, p. 379.

- ^ Cohen 1977, pp. 381–382.

- ^ Cohen 1977, p. 390In any event, the Zionists sabotaged these unofficial Arab-British negotiations by giving them premature publicity and the British, believing that the Arabs had violated the spirit of their negotiations, decided in September to despatch an extra army division to Palestine and to declare martial law.

- ^ Galnoor 2009, p. 77.

- ^ Galnoor 2009, p. 80.

- ^ Flapan 1987, p. 22.

- ^ Mayer 1983, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Jankowski 1981, pp. 429–431.

- ^ Jankowski 1981, p. 430.

- ^ Jankowski 1981, pp. 397–403.

- ^ Jankowski 1981, p. 439.

- ^ Cohen 1981, p. 587.

- ^ Jankowski 1981, p. 438.

- ^ a b Cohen 1981, p. 593. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTECohen1981593" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Buheiry, Marwan R. (1989) The Formation and Perception of the Modern Arab World. Studies by Marwan R Buheiry. Edited by Lawrence I. Conrad. Darwin Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-87850-064-2. p.177

Sources

[edit]Journal Articles

[edit]Eppel, Michael (2012). "The Arab States and the 1948 War in Palestine: The Socio-Political Struggles, the Compelling Nationalist Discourse and the Regional Context of Involvement". Middle Eastern Studies. 48 (1): 1–31. JSTOR 23217085 – via JSTOR.

Galnoor, Itzhak (2009). "The Zionist Debates on Partition (1919-1947)". Journal of Palestine Studies. 14 (2): 74–87. JSTOR 30245854 – via JSTOR.

Hassanein Heikal, Mohamed (1998). "Mohamed Hassanein Heikal: Reflections on a Nation in Crisis, 1948". Journal of Palestine Studies. 18 (1): 112–120. doi:10.2307/2537598. JSTOR 2537598 – via JSTOR.

Khalidi, Walid (1998). "Selected Documents on the 1948 Palestine War". Journal of Palestine Studies. 27 (3): 60–105. doi:10.2307/2537835. JSTOR 2537835 – via JSTOR.

Eppel, Michael (1996). "Syrian-Iraqi Relations during the 1948 Palestine War". Middle Eastern Studies. 32 (3): 74–91. JSTOR 4283808 – via JSTOR.

Mayer, Thomas (1986). "Arab Unity of Action and the Palestine Question, 1945-48". Middle Eastern Studies. 22 (3): 331–349. JSTOR 4283126 – via JSTOR.

Mayer, Thomas (1986). "Egypt's 1948 Invasion of Palestine". Middle Eastern Studies. 22 (1): 20–36. JSTOR 4283094 – via JSTOR.

Jankowski, James (1981). "The Government of Egypt and the Palestine Question, 1936-1939". Middle Eastern Studies. 17 (4). Taylor & Francis, Ltd: 20–36. JSTOR 427-453 – via JSTOR.

Cohen, Michael J. (1977). "Secret Diplomacy and Rebellion in Palestine, 1936-1939". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 8 (3): 379–404. JSTOR 162527 – via JSTOR.

Cohen, Michael J. (1981). "Appeasement in the Middle East: The British White Paper on Palestine, May 1939". The Historical Journal. 16 (3). Cambridge University Press: 571–596. JSTOR 2638205 – via JSTOR.

Books

[edit]Morris, Benny (2008). 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300126969.

Doran, Michael (1999). Pan-Arabism before Nasser: Egyptian Power Politics and the Palestine Question. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195160086.

Mayer, Thomas (1983). Egypt and the Palestine Question: 1936-1945. Klaus Schwarz Verlag. ISBN 9783922968207.

Flapan, Simha (1987). The Birth of Israel: Myths and Realities (PDF). New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-55888-X.