Draft:Assassination of Umberto I of Italy

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Bearcat (talk | contribs) 3 months ago. (Update) |

| Assassination of Umberto I of Italy | |

|---|---|

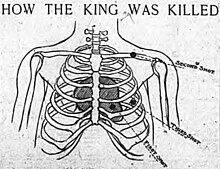

British illustration of the act. | |

| Location | Via Matteo da Campione, Monza (Kingdom of Italy) |

| Coordinates | 45°35′28″N 9°16′08″E / 45.59111°N 9.26889°E |

| Date | July 29, 1900 Around 9:30 p.m. |

Attack type | Assassination |

| Weapon | .38 caliber revolver |

| Deaths | 1 |

| Perpetrator | Gaetano Bresci |

| Convictions | Anarchism Radicalism |

The Assassination of Umberto I of Italy, the Italian king, took place on July 29, 1900 on the Matteo da Campione street in Monza. King Umberto I of Italy was shot three of four times by Italian anarchist Gaetano Bresci during the sport ceremony and died few minutes later. Bresci commited the act as the revenge for the Bava Beccaris massacre, violant action against the protesters in Milan in 1898. Before this event, Umberto I was targeted twice, in 1879 and 1898, but in both cases he survived the assassination attempt.

Prelude

[edit]In the second half of the 19th century, radical anarchism in Italy was on the rise. Having succeeded his father Victor Emmanuel II on 9 January 1878, Umberto I became the main target for the anarchists almost immediately. Just ten months after ascending the throne, on 17 November 1878, he was attacked while he was visiting Naples with his wife, son and Prime Minister Benedetto Cairoli.[1] King was suddenly attacked with a knife by the Lucanian anarchist Giovanni Passannante, while shouting: "Long live Orsini! long live the universal republic".[2] The king managed to defend himself and an officer of the Cuirassiers in his entourage lunged at the attacker, wounding him on the head with his sabre, while Cairoli, in an attempt to block the attacker, was wounded in the thigh. Umberto I suffered just a light cut on his arm.[3] The violent attempt generated numerous protest marches, both against and in favor of the attacker, and clashes between the police and anarchists occured. Following the attempted assassination, the Chief of Police Luigi Berti was forced to resign a month later. Passannante was later sentenced to life imprisonment and transferred to prison where he began to show serious mental problems,[4] committing suicide in 1910.

The second attempt for the kings life occured on 22 April 1897, in Rome. Umberto was riding in his carriage at the Capannelle Racecourse[5] when the anarchist Pietro Acciarito rushed towards his carriage armed with a knife.[6] The king, having promptly noticed the weapon in his hand, was able to easily dodge the anarchist's attempt to strike him and remained unharmed. Having just managed to scratch the royal carriage, Acciarito then calmly walked away and, in the confusion that followed his gesture, was stopped only after he had walked about 50 metres from the place of act. Acciarito was then arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment. Like Passannante, his sentence was very harsh and had serious consequences on his mental health.[6]

Bava Beccaris massacre

[edit]Between 6 and 8 May 1898 the population of Milan took to the streets to protest against working conditions and the increase in the price of bread in the previous months, in which also women and children participated.[7] The Italian government of Antonio Starabba di Rudinì declared a state of siege and gave full powers to General of the Royal Italian Army Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris to repress the revolt. The results of the so-called Bava Beccaris massacre were drastic: 81 people were killed and 450 injured.[8]

After the events in Milan, on 5 June Bava Beccaris received from the king the honour of Grand Officer of the Military Order of Savoy[9] and on 4 July 1898 he was appointed Senator of the Kingdom by the king, a position he held until 1924, at the dawn of fascism , of which he supported.

The bloody repression of the revolt, the honour and the nomination of Bava Beccaris as Senator aroused strong indignation among part of the population, including Gaetano Bresci.

Preparations

[edit]

Bresci, young weaver and anarchist originally from the city of Prato, was in Italy twice arrested for leftist activities and organising labor strikes, therefore in 1897 he immigrated to the United States.[10] In 1898, while living in Paterson, New Jersey, Bresci received news of the Bava Beccaris massacre[11]and after that swore revenge against Umberto I, who he held personally responsible for the massacre.

On 17 May he embarked from New York and on 26 May he disembarked in Le Havre, carrying the .38 caliber revolver, which he bought in Paterson. Together with two others he visited the Paris Exhibition and then returned to Prato, his native town. There he remained until 18 July, when he moved to his sister's house in San Pietro. On the evening 21 July he then reached Bologna, then on 24 July he arrived to Milan[12] where he rented a room in a guesthouse. On 27 July he was present in Monza,[13] where he rented another room and began to explore the area and the surroundings of Villa Reale also asking for some news about the movements of the royal family up until the day of the attack.

Attack

[edit]

On 29 July evening he king had been invited to the closing ceremony of the Forti e Liberi gymnastics club in Matteo da Campione street:[14] after arriving by carriage and watching the gymnastics exercises and the award speech by prof. Draghino, he set off towards the carriage at 9:30 pm to return to Villa Reale. Meanwhile Bresci took a position close to the main gate waiting the carriage to pass by.[15] As the carriage was leaving the gate, where there was a crowd of gymnasts forcing the vehicle to slow down, Bresci approached and hit Umberto three times with his revolver, firing the fourth shot blank.[16]

Monarch was hit both in the face and in the throat. The horses of the royal carriage became restless and the king was immediately taken to the Royal Villa, but arrived there lifeless. The king, entrusted to the surgeons Vincenzo Vercelli and Attilio Savio, was declared dead by them at 10:40 p.m. Meanwhile Bresci was surrounded by the Carabinieri, after the short fight captured and taken to the guardhouse of the Carabinieri barracks.

Royal funeral

[edit]

On July 30 members of the royal family arrived in Monza. The new king Victor Emmanuel III interrupted the cruise in the Mediterranean with his wife Elena of Montenegro, landed in Reggio Calabria port, and then reached Naples, where he met with the former Prime Minister Francesco Crispi. From here the new rulers arrived by train at 6:30 p.m. at the Monza station, guarded by the "Genova Cavalleria" Regiment. Victor Emanuel was thus able to meet his mother and see his father's body in the chapel of rest.

On 8 August, after a ceremony in the funeral chapel of Villa Reale, the body of Umberto I was accompanied to the station, from where it left for Rome in a special carriage with the high clergy and court dignitaries, who had also been entrusted with the Iron Crown. At 6:30 p.m. train arrived at Rome Termini station, from where the funeral procession, led by General Amedeo Avogadro, again accompanied by the crowd, reached the Pantheon, where the body was buried on 9 August 1900.[17]

Trial and conviction

[edit]

On 29 August 1900, at 9:00 am, the trial against Gaetano Bresci opened at the Assize Court of Milan.[18] He was defended by the former anarchist Francesco Saverio Merlino,[19] after Filippo Turati had refused so as not to compromise the Italian Socialist Party and his political career. The sentence arrived the very same day in the late afternoon, at 6 pm: Bresci was sentenced to life imprisonment, made more severe by solitary confinement for the first seven years in the Santo Stefano penitentiary on the island of Ventotene, in a nine-square-meter cell built to guard him. Word Vengeance[20] had been carved into the wall. Suspicious circumstances of this event are leading to theories, than Bresci was murdered by his guards.[21]

Facing the harsh prison conditions, Italian govenrment was worried about the attempt to set Bresci free by the members of Italian anarchist groups, preventing this to set additional guards. On 22 May 1901,[22] Bresci was found hanging by the neck in his cell.

Bresci's wife and daughter were forced to leave their home in West Hoboken, New Jersey.[23]

The assassination directly inspired some other anarchist assassins, like Polish-American Leon Czolgosz,[24] who commited the assassination of William McKinley, 25th president of the United States.

Memory

[edit]

At the site of the attack in Monza, the Expiatory Chapel was built in 1910 in memory of the murdered king, designed by the architect Giuseppe Sacconi,[25] at the behest of his son, Victor Emmanuel III. Deciesed king was also themed in works of by the poets Giovanni Pascoli or Adolfo Resplendino.

Bresci's personal effects, including the gun with which he killed Umberto I with some bullets, are kept at the Criminological Museum in Rome.[26]

The assassination is pictured in Italian movie L'ultimo giorno del Re (The Last Day of the King) directed by Ettore Radice from 2020.[27]

See also

[edit]- Gaetano Bresci

- Umberto I of Italy

- Anarchism in Italy

- History of Monza

- List of assassinations in Europe

Citations

[edit]- ^ George Boardman Taylor, Italy and the Italians, America Baptist publication society, 1898, p. 88

- ^ Galzerano, p. 396

- ^ Fetherling, George (2011). The Book of Assassins. Random House of Canada. ISBN 9780307369093. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Galzerano, 642

- ^ Nawrocki, Norman (2013). Cazzarola!: Anarchy, Romani, Love, Italy (A Novel). PM Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-16-0486-315-4.

- ^ a b Pernicone, Nunzio (2011). "The Case of Pietro Acciarito: Accomplices, Psychological Torture, and "Raison d'État"". Michigan State University Press. 5 (1): 67–104. JSTOR 41889948.

- ^ Jensen, Richard Bach (2014). "The Assassination of Umberto I of Italy". The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History, 1878–1934. Cambridge University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-107-03405-1. OCLC 936070232.

- ^ Jensen, Richard Bach (2014). "The Assassination of Umberto I of Italy". The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History, 1878–1934. Cambridge University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-107-03405-1. OCLC 936070232.

- ^ Pernicone, Nunzio; Ottanelli, Fraser M (2018). Assassins Against the Old Order: Italian Anarchist Violence in Fin De Siècle Europe. University of Illinois Press. p. 144. doi:10.5406/j.ctv513d7b. ISBN 978-0-252-05056-5. OCLC 1050163307.

- ^ Pernicone, Nunzio; Ottanelli, Fraser M (2018). Assassins Against the Old Order: Italian Anarchist Violence in Fin De Siècle Europe. University of Illinois Press. p. 135. doi:10.5406/j.ctv513d7b. ISBN 978-0-252-05056-5. OCLC 1050163307.

- ^ Levy, Carl (2007). "The Anarchist Assassin and Italian History, 1870s to 1930s". In Gundle, Stephen; Rinaldi, Lucia (eds.). Assassinations and Murder in Modern Italy. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 211. doi:10.1057/9780230606913_17. ISBN 978-02306-0691-3. OCLC 314799595.

- ^ Kemp, Michael (2018). "The Cook, the Blacksmith, the King and the Weaver". Bombs, Bullets and Bread: The Politics of Anarchist Terrorism Worldwide, 1866–1926. McFarland & Company. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-1-4766-3211-7. OCLC 1043054028. Retrieved 3 May 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pernicone, Nunzio; Ottanelli, Fraser M (2018). Assassins Against the Old Order: Italian Anarchist Violence in Fin De Siècle Europe. University of Illinois Press. p. 148-149. doi:10.5406/j.ctv513d7b. ISBN 978-0-252-05056-5. OCLC 1050163307.

- ^ Gremmo, Roberto (2000). Gli anarchici che uccisero Umberto I ̊: Gaetano Bresci, il "Biondino" e i tessitori biellesi di Paterson. Storia Ribelle. p. 123. Retrieved 2024-09-08.

- ^ Kemp, Michael (2018). "The Cook, the Blacksmith, the King and the Weaver". Bombs, Bullets and Bread: The Politics of Anarchist Terrorism Worldwide, 1866–1926. McFarland & Company. pp. 60–64. ISBN 978-1-4766-3211-7. OCLC 1043054028. Retrieved 3 May 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ Holzer, Jacob C.; Dew, Andrea J.; Recupero, Patricia R.; Gill, Paul (2022). Lone-actor Terrorism: An Integrated Framework. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-092979-4.

- ^ Steed, Henry Wickham (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 872–873.

- ^ Carey, George W. (December 1978). "The Vessel, The Deed, and the Idea: Anarchists in Paterson, 1895–1908". Antipode. 10–11 (3–1): 46–58. Bibcode:1978Antip..10...46C. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.1978.tb00115.x. ISSN 0066-4812. OCLC 5155744186.

- ^ Levy, Carl (2007). "The Anarchist Assassin and Italian History, 1870s to 1930s". In Gundle, Stephen; Rinaldi, Lucia (eds.). Assassinations and Murder in Modern Italy. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 21ž-217. doi:10.1057/9780230606913_17. ISBN 978-02306-0691-3. OCLC 314799595.

- ^ Carey, George W. (December 1978). "The Vessel, The Deed, and the Idea: Anarchists in Paterson, 1895–1908". Antipode. 10–11 (3–1): 46–58. Bibcode:1978Antip..10...46C. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.1978.tb00115.x. ISSN 0066-4812. OCLC 5155744186.

- ^ Levy, Carl (2007). "The Anarchist Assassin and Italian History, 1870s to 1930s". In Gundle, Stephen; Rinaldi, Lucia (eds.). Assassinations and Murder in Modern Italy. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 214–215. doi:10.1057/9780230606913_17. ISBN 978-02306-0691-3. OCLC 314799595.

- ^ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, p. 166 sfnm error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFPerniconeOttanelli2018 (help); Kemp 2018, p. 62 sfnm error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFKemp2018 (help); Simon 2022, p. 20.

- ^ New York Herald: 3. 1 August 1900.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Jensen, Richard Bach (2014). "The Assassination of Umberto I of Italy". The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History, 1878–1934. Cambridge University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-107-03405-1. OCLC 936070232.

- ^ "Royal Expiatory Chapel". Italia.it. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ "Rome, The Museo Criminologico". The Ghoul Stories. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Apicella, Barbara. "L'ultimo giorno del re: il docufilm sul regicidio a Monza finisce in tv". MonzaToday. MonzaToday. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Castañeda, Christopher J. (2017). "Times of Propaganda and Struggle: El Despertar and Brooklyn's Spanish Anarchists, 1890–1905". In Goyens, Tom (ed.). Radical Gotham: Anarchism in New York City from Schwab's Saloon to Occupy Wall Street. University of Illinois Press. pp. 77–99. ISBN 978-0-252-09959-5. OCLC 985447628.

- Kemp, Michael (2018). "The Cook, the Blacksmith, the King and the Weaver". Bombs, Bullets and Bread: The Politics of Anarchist Terrorism Worldwide, 1866–1926. McFarland & Company. pp. 60–64. ISBN 978-1-4766-3211-7. OCLC 1043054028. Retrieved 3 May 2024 – via Google Books.

- Pernicone, Nunzio; Ottanelli, Fraser M (2018). Assassins Against the Old Order: Italian Anarchist Violence in Fin De Siècle Europe. University of Illinois Press. doi:10.5406/j.ctv513d7b. ISBN 978-0-252-05056-5. OCLC 1050163307.

- Simon, Jeffrey D. (2022). America's Forgotten Terrorists: The Rise and Fall of the Galleanists. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-1-640-12404-2. OCLC 1302736396. Retrieved 3 May 2024 – via Google Books.

External links

[edit]