Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Or a Mis-Spent Life

| Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Or a Mis-Spent Life | |

|---|---|

Title page for published play | |

| Written by | Luella Forepaugh and George F. Fish |

| Based on | Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson |

| Characters | Henry Jekyll/Edward Hyde |

| Date premiered | March 14, 1897 |

| Place premiered | Forepaugh's Family Theatre |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | |

| Setting | London |

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Or a Mis-Spent Life is a four-act play written in 1897 by Luella Forepaugh and George F. Fish. It is an adaptation of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, an 1886 novella written by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. The story focuses on Henry Jekyll, a respected London doctor, and his involvement with Edward Hyde, a loathsome criminal. After Hyde murders a vicar, Jekyll's friends suspect he is helping the killer, but the truth is that Jekyll and Hyde are the same person. Jekyll has developed a potion that allows him to transform himself into Hyde and back again. When he runs out of the potion, he is trapped in his Hyde form and commits suicide.

Forepaugh and Fish wrote the adaptation for the repertory company at a family theater Forepaugh managed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After Forepaugh and Fish left the theater business, the play was published in 1904 for the use of other theater companies. A 1908 silent film was based on the play.

Plot

[edit]In the first act, attorney J. G. Utterson is visiting with friends outside a London vicarage. The vicar, Reverend Edward Leigh, relates a story about how he intervened when he saw a girl trampled by a man named Edward Hyde. Utterson is dismayed to hear the name Edward Hyde, because his friend and client, Dr. Henry Jekyll, recently made a new will that gives his estate to a mysterious friend named Edward Hyde. After the vicar leaves, Dr. Lanyon arrives. Utterson asks Lanyon if he knows Hyde, but he does not; he and Jekyll have become more distant recently due to scientific disagreements. Jekyll, who lives next door to the vicarage, passes by on his way to see a patient. Utterson expresses his concern about Jekyll's will, but Jekyll refuses to consider changing it.

After Jekyll and Utterson leave, Lanyon speaks to the vicar's daughter, Alice Leigh, who admits to being in love with Jekyll. Alice sees that Lanyon does not approve, and she asks Jekyll about it when he returns. He says she would not understand and begins talking about the dual presence of good and evil in men. Suddenly, Jekyll feels "the change approaching" and runs home. Before he reaches his door, he transforms into Hyde in view of the audience, but not Alice, who has gone to the other end of the stage. Hyde menaces Alice, who calls for her father. The vicar comes out of the vicarage and is clubbed with a stick by Hyde. Hyde runs away; Jekyll returns and asks who has attacked them. With his dying breath, the vicar says it was Hyde.

In the second act, Inspector Newcomen shows Utterson part of the walking stick that Hyde used to kill Howell. Utterson recognizes it as one he gave to Jekyll. Newcomen vows to find the killer, and asks to interview Alice, who has been staying with Utterson since the murder. Jekyll visits Utterson with a letter from Hyde, claiming he has departed. When Jekyll leaves, Utterson's assistant, Mr. Guest, points out that the handwriting on the letter is very similar to Jekyll's.

When Utterson leaves, Jekyll returns and delivers a monologue confessing that he is the murderer. After a brief conversation with Alice, Jekyll leaves. Utterson and Newcomen return, saying they play to lay a trap for Hyde. Alice insists on going with them. As they wait outside the vicarage, they see Hyde approaching Jekyll's house. He is talking to himself about his enjoyment of hurting women and children, and his hatred of Jekyll. When Utterson confronts him, Hyde rushes into Jekyll's house. When Utterson, Newcomen, and Alice pursue him, they find Jekyll instead.

In the third act, Utterson and the police discuss their failure to catch Hyde. One of Jekyll's servants, Poole, says Hyde is allowed free access to Jekyll's house. Alice overhears this and is distraught to learn that Jekyll has helped her father's killer. Alice resolves to confront Jekyll about this. In the act's final scene, Lanyon waits at home with drugs from Jekyll's laboratory, retrieved on written instructions from Jekyll. Hyde arrives to retrieve the drugs. He mixes them with water and drinks the resulting potion in front of Lanyon, after which he transforms into Jekyll.

The final act begins four months later. Lanyon has died of shock and Jekyll is refusing to see Utterson or Alice. Alice is still angry that Jekyll is believed to have helped Hyde. Poole visits to say he fears Jekyll has been murdered. Someone is secluded in Jekyll's laboratory, claiming to be him and communicating mostly through written notes, but Poole thinks it is someone else. Utterson and Alice agree to accompany Poole to confront the person in Jekyll's laboratory.

In the laboratory, Jekyll gives a monologue explaining that he can no longer find the ingredients for his potion and therefore will soon revert to Hyde, without the ability to transform back. Alice comes to the laboratory and sees that Jekyll appears ill. He tells her they will marry when he is better, but when she leaves he monologues that he will die soon, then he transforms into Hyde. When Utterson and Poole come to the laboratory, Hyde commits suicide by drinking poison, declaring that he has also killed Jekyll.

Characters

[edit]- Dr. Jekyll / Mr. Hyde

- J. C. Utterson, a lawyer of Chancery Lane

- Rev. Edward Leigh, a vicar and father of Alice

- Doctor Lanyon, of Cavendish Square

- Inspector Newcomen, of Scotland Yard

- Poole, butler of Dr. Jekyll

- Guest, Utterson's clerk

- McSweeny, a policeman

- Wilson, a detective

- James, footman to Lady Durswell

- Biddy, Jekyll's cook

- Alice Leigh, the vicar's daughter

History

[edit]

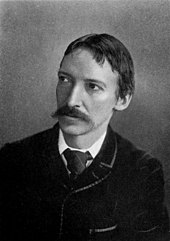

The Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson wrote Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in 1885.[1] In January 1886, it was published in the United Kingdom by Longmans, Green & Co. It was published that same month by Charles Scribner's Sons in the United States,[2] where it was also frequently pirated due to the lack of copyright protections in the US for works originally published in the UK.[3] Despite the opportunity to adapt without authorization, the actor Richard Mansfield secured permission for both the American and British stage rights in early 1887. Mansfield asked Boston writer Thomas Russell Sullivan to create the script. Their authorized adaptation debuted at the Boston Museum on May 9, 1887, under the title Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.[4][5] A competing, unauthorized adaptation was written by John McKinney in collaboration with the actor Daniel E. Bandmann. It also used the title Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and it opened at Niblo's Garden on March 12, 1888.[6][7] Both of these adaptations were subsequently performed on tour in other cities.

Luella Forepaugh became the manager of Forepaugh's Family Theatre, a repertory theater in Philadelphia, when her husband, John A. Forepaugh, became ill and died in 1895.[8] In 1897, she and George F. Fish wrote a new adaptation of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde for the theater's company. Their version is very similar to McKinney and Bandmann's 1888 adaptation.[9] It debuted at Forepaugh's on March 14, 1897, with the company's leading man, George Learock, in the dual role of Jekyll and Hyde.[10] The debut was a matinée, with cinematograph images projected between the acts for the entertainment of children in the audience, and patrons were given souvenir copies of Stevenson's novella with their admission.[11]

Forepaugh and Fish married in 1899, and they decided to leave the theater to start the Luella Forepaugh-Fish Wild West Show, which opened in St. Louis, Missouri on April 17, 1903.[12] Their adaptation of the Jekyll and Hyde story was published by Samuel French in 1904 under the title Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Or a Mis-Spent Life, for use by other stock theater companies.[13]

Reception

[edit]The play's debut received positive reviews in the local Philadelphia papers, The Times[14] and The Philadelphia Inquirer.[15] Theater historian Brian A. Rose compared it unfavorably to Sullivan's 1887 adaptation, saying the earlier version had more nuance. In contrast, he described Forepaugh and Fish's version as a "melodramatic potboiler" that lacked subtlety and played to stereotypes.[16]

Robert Louis Stevenson was not happy with any of the stage play adaptations, since he said they all added a sex angle to the story that was not in the original novel, which in fact featured no major female characters. He called the plays "ugly" and said, "Hyde (was) no more sexual than another, but (was) the essence of cruelty and malice and selfishness and cowardice, and these are the diabolic in man....not this great wish to have a woman, that they make such a cry about." He also complained that Hyde was supposed to appear younger than Jekyll in the story and "not the other way around as it appeared in the (plays)".[17]

Adaptations

[edit]The 1908 silent movie Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was a filmed theatrical performance of an abbreviated version of the 1897 play by Forepaugh and Fish.[18]

References

[edit]- ^ Cooper 1948, p. 48

- ^ Geduld 1983, p. 185

- ^ Cooper 1948, p. 56

- ^ Danahay & Chisholm 2011, loc 565–576

- ^ Rose 1996, p. 51

- ^ Winter 1910, p. 264

- ^ Miller 2005, pp. 24–25

- ^ Curry 1994, p. 125

- ^ "Dramatizations: stage adaptations of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde". The Robert Louis Stevenson Archive. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ "Last Night's Bills at the Theatres: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde at Forepaugh's". The Philadelphia Inquirer. March 16, 1897. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "To Be Seen at the Theatres". The Times. March 14, 1897. p. 20 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kuntz 2010, p. 116

- ^ Rose 1996, p. 37

- ^ "The Round of the Theatres". The Times. March 16, 1897. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Programs of the Week: Forepaugh's-Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde". The Philadelphia Inquirer. March 14, 1897. p. 20 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rose 1996, pp. 52–53

- ^ Haberman, Steve (2003). Silent Screams. Midnight Marquee Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-936168-15-6.

- ^ Nollen 1994, p. 168

Works cited

[edit]- Cooper, Lettice (1948). Robert Louis Stevenson. Denver: Alan Swallow. OCLC 798717.

- Curry, Jane Kathleen (1994). Nineteenth-century American Women Theatre Managers. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29141-1. OCLC 467972353.

- Danahay, Martin A. & Chisholm, Alex (2011) [2004]. Jekyll and Hyde Dramatized (Kindle ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1870-1. OCLC 55797764.

- Geduld, Harry M., ed. (1983). The Definitive Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde Companion. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-9469-7. OCLC 9045100.

- Kuntz, Jerry (2010). A Pair of Shootists: The Wild West Story of S.F. Cody and Maud Lee. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4149-7. OCLC 824698866.

- Miller, Renata Kobetts (2005). Recent Reinterpretations of Stevenson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: Why and How This Novel Continues to Affect Us. Lewiston, New York: The Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-5991-X. OCLC 845947485.

- Nollen, Scott Allen (1994). Robert Louis Stevenson: Life, Literature and the Silver Screen. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 0-89950-788-3. OCLC 473576741.

- Rose, Brian A. (1996). Jekyll and Hyde Adapted: Dramatizations of Cultural Anxiety. Contributions in Drama and Theatre Studies. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29721-5. OCLC 32921958.

- Winter, William (1910). The Life and Art of Richard Mansfield: Volume One. New York: Moffat, Yard and Company. OCLC 1513656.

External links

[edit]- Full text of published play at Internet Archive