Jasper Johns

Jasper Johns | |

|---|---|

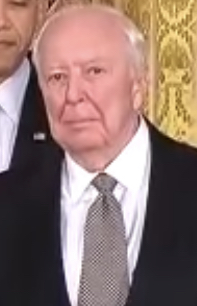

Johns receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011 | |

| Born | Jasper Johns Jr. May 15, 1930 Augusta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Known for | |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Abstract expressionism, Neo-Dada, pop art |

| Awards |

|

Jasper Johns (born May 15, 1930) is an American painter, sculptor, draftsman, and printmaker. Considered a central figure in the development of American postwar art, he has been variously associated with abstract expressionism, Neo-Dada, and pop art movements.[1][2]

Johns was born in Augusta, Georgia, and raised in South Carolina. He graduated as valedictorian from Edmunds High School in 1947 and briefly studied art at the University of South Carolina before moving to New York City and enrolling at Parsons School of Design. His education was interrupted by military service during the Korean War. After returning to New York in 1953, he worked at Marboro Books and began associations with key figures in the art world, including Robert Rauschenberg, with whom he had a romantic relationship until 1961.[3][4] The two were also close collaborators, and Rauschenberg became a profound artistic influence.[5]

Johns's art career took a decisive turn in 1954 when he destroyed his existing artwork and began creating paintings of flags, maps, targets, letters, and numbers for which he became most recognized. These works, characterized by their incorporation of familiar symbols, marked a departure from the individualism of Abstract Expressionist style and posed questions about the nature of representation. His use of familiar imagery, such as the American flag, played on the ambiguity of symbols, and this thematic exploration continued throughout his career in various mediums, including sculpture and printmaking.

Among other honors, Johns received the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 1988, the National Medal of Arts in 1990, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011.[6] He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1973 and the American Philosophical Society in 2007.[7] He has supported the Merce Cunningham Dance Company and contributed significantly to the National Gallery of Art's print collection. Johns is also a co-founder of the Foundation for Contemporary Arts. He currently lives and works in Connecticut. In 2010, his 1958 painting Flag was sold for a reported $110 million in a private transaction, becoming the most expensive artwork sold by a living artist.[8][9]

Life

[edit]Born in Augusta, Georgia, Jasper Johns spent his early life in Allendale, South Carolina, with his paternal grandparents after his parents divorced. He began drawing at the age of three and knew very early on that he wanted to be an artist, despite having little exposure to the arts where he grew up. His paternal grandfather's first wife, Evalina, painted landscapes that hung in the homes of several family members. These paintings were the only artworks Johns remembers seeing in his youth.[10] Following his grandfather's death in 1939, Johns spent a year living with his mother and stepfather in Columbia, South Carolina, and then six years living with his Aunt Gladys on Lake Murray, South Carolina. He spent summer holidays with his father, Jasper, Sr., and stepmother, Geraldine Sineath Johns, who encouraged his art by buying materials for him to draw and paint. He graduated as valedictorian of Edmunds High School (now Sumter High School) class of 1947 in Sumter, South Carolina, where he once again lived with his mother and her family.[11]

Johns studied art for a total of three semesters at the University of South Carolina at Columbia, from 1947 to 1948.[12] Encouraged by his professors, he then moved to New York City and enrolled briefly at the Parsons School of Design in 1949.[12] In 1951, Johns was drafted into the army during the Korean War, serving for two years, first in Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and then in Sendai, Japan.[12]

Returning to New York in the summer of 1953, Johns worked at Marboro Books and began to meet some of the artists who would be formative in his early career. These included Sari Dienes, Rachel Rosenthal, and Robert Rauschenberg, with the latter of whom Johns began a romantic and artistic relationship that would last until 1961.[3][13][14] During the same period Johns was strongly influenced by the choreographer Merce Cunningham and his partner, the composer John Cage.[15][16] Working together they explored the contemporary art scene, and began sharing their ideas on art.[12]

In March 1957, while visiting Rauschenberg's studio, the gallery owner Leo Castelli asked to see Johns's art.[12] As Castelli recalled: "So we went down. It was just the floor below. There was a fantastic display of flags and targets. You know the target with the plastic eyes, the one with the faces. The Green Target was at the Jewish Museum, but there was a big white flag, a smaller white flag, numbers, the alphabet, anything—all those great masterpieces."[17] Castelli immediately offered Johns an exhibition. His first solo show at the Leo Castelli Gallery, held in early 1958, was well received; all but two of the eighteen works on view sold. Alfred H. Barr Jr., the founding director of New York's Museum of Modern Art, purchased three paintings from the show, which were the first works by Johns to enter a museum collection.[18]

Johns has lived and worked in various homes and studios in New York City throughout his career and, from 1973 to 1987, maintained a rustic 1930s farmhouse with a glass-walled studio in Stony Point, New York. He began visiting the Caribbean island of Saint Martin in the late 1960s, buying property there in 1972, and, later, building a home and studio, for which Philip Johnson was the principal designer.[19] Johns currently lives and works in Sharon, Connecticut.

Following his death, the artist plans to transform his 170-acre property in Sharon, Connecticut, into an artists' residency. He has lived there since the 1990s. It will provide a live-work space for 18 to 24 artists at a time and will be open to visual artists, poets, musicians, dancers.[20][21]

Work

[edit]Painting

[edit]In 1954, Johns destroyed all of his previous artwork still in his possession and began the paintings for which he is best known: depictions of flags, maps, targets, letters, and numbers.[22][23] His use of such symbols differentiated his paintings from the gestural abstraction of the Abstract Expressionists, whose works were often understood as expressive of the individual personality or psychology of the artist.[24][25] With well-known motifs imported into his art, his paintings could be read as both representational (a flag, a target) and as abstract (stripes, circles).[23][12] Some art historians and museums characterize his choice of subjects as freeing him from decisions about composition.[23] Johns has remarked: "What's interesting to me is the fact that it isn't designed, but taken. It's not mine,"[26] or, that these motifs are "things the mind already knows."[12]

His early encaustic painting Flag (1954–55), painted after having a dream of it, marks the beginning of this new period.[22] The motif allowed Johns to create a painting that was not completely abstract because it depicts a symbol (the American flag), yet it draws attention to the design of the symbol itself. The work evades the personal because it depicts a national symbol, and yet, it maintains a sense of the handmade in Johns's wax brushstrokes; it is neither a literal flag, nor a purely abstract painting.[27][12][22] The work thus raises a set of complex questions with no clear answers through its combination of symbol and medium.[12][28][29] Indeed, Alfred H. Barr could not convince the trustees of the Museum of Modern Art to directly acquire the painting from Johns's first solo show, as they were afraid its ambiguity might lead to boycott or attack by patriotic groups during the Cold War climate of the late 1950s.[1][30] Barr was, however, able to arrange for the architect Philip Johnson to buy the painting and later donate it to the museum in 1973.[10] The flag remains one of Johns's most enduring motifs; the art historian Roberta Bernstein recounts that "between 1954 and 2002, he employed virtually his full array of materials and techniques in twenty-seven paintings, ten individual or editioned sculptures, fifty drawings, and eighteen print editions that depict the flag as the primary image."[10]

Johns is also known for including three-dimensional objects in his paintings. These objects can be either found (the ruler in Painting with Ruler and "Gray," 1960) or specifically made (the plaster reliefs in Target with Four Faces, 1955). This practice challenges the typical conception of painting as a two-dimensional realm.[31][32] Johns's early and enduring use of the medium of encaustic also presented the opportunity to experiment with texture. An ancient technique, encaustic is a process whereby melted wax mixed with pigment is applied and "burned into" a support. The method allowed Johns to preserve the discrete quality of individual brushstrokes, even when layered, creating textured yet, at times, transparent surfaces.[33][10] Johns's 2020 work Slice reproduces a drawing of a knee by Jéan-Marc Togodgue, a Cameroonian emigre student basketball player who attended the Salisbury School near Johns's estate in Sharon.[34] Johns's use of Togodgue's artwork without first notifying him led to a dispute that was settled amicably.[35][34][36]

Sculpture

[edit]Johns made his first sculpture, Flashlight I, in 1958. Many of his earliest sculptures are single, freestanding objects modeled from a material called Sculp-metal, a pliable metallic medium that could be applied and manipulated much like paint or clay.[37] During this period, he also employed casting techniques to make objects out of plaster and bronze. Some of these objects are painted to suggest a certain sense of verisimilitude; Painted Bronze (1960), for example, depicts a can painted with the Savarin Coffee label. Filled with cast paintbrushes, the work recalls an object one might find on an artist's studio table.

Numbers (2007), which depicts his now classic pattern of stenciled numerals repeated in a grid, and is the largest single bronze Johns has made to date.[38] Another sculpture from this period, a double-sided relief titled Fragment of a Letter (2009), incorporates part of a letter from Vincent van Gogh to his friend, the artist Émile Bernard. On one side of the relief, Johns pressed each letter of van Gogh's words into the wax model. On the other side, he spelled each letter in the American Sign Language alphabet using stamps he designed. Johns signed the wax model with impressions of his own hand, his name finger-spelled in two vertical rows.[39]

Prints

[edit]Johns began experimenting with printmaking techniques in 1960, when Tatyana Grosman, the founder of Universal Limited Art Editions, Inc. (ULAE), invited him to her printmaking studio on Long Island. Beginning with lithographs that explore the common objects and motifs for which he is best known, such as Target (1960), Johns continued to work closely with ULAE, publishing over 180 editions in a variety of printmaking techniques to investigate and develop existing compositions.[40] Initially, lithography suited Johns and enabled him to create print versions of iconic depictions of flags, maps, and targets that filled his paintings. In 1971, Johns became the first artist at ULAE to utilize the handfed offset lithographic press, resulting in Decoy — an image realized as a lithograph before it became a drawing or painting.

Johns has worked with other printmakers throughout his career, producing lithographs and lead reliefs at Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles;[41] screenprints with Hiroshi Kawanishi at Simca Prints in New York from 1973–75;[42] and intaglios published by Petersburg Press at Atelier Crommelynck in Paris from 1975–90, including a collaboration with the author Samuel Beckett that resulted in Foirades/Fizzles (1976), a book of five text fragments by Beckett in French and English and 33 intaglios by Johns.[43] He produced Cup 2 Picasso as an offset lithograph for the June 1973 issue of the magazine XXe siècle and, in 2000, completed an edition of 26 linocuts printed by the Grenfell Press and published by Z Press to accompany Jeff Clark's Sun on 6.[44][45] For the May 2014 issue of Art in America, he created an unnumbered black-and-white off-set lithograph depicting many of his signature motifs.[46]

In 1995, Johns hired master printmaker John Lund and began to construct his own printmaking studio on his property in Sharon, Connecticut. Low Road Studio was officially founded in 1997 as Johns's own publishing imprint.[18]

Collaborations

[edit]For decades Johns worked with others to raise both funds and attention for Merce Cunningham's Dance Company. He assisted Robert Rauschenberg in some of his 1950s designs for Cunningham's sets and costumes. In spring 1963, Johns and John Cage cofounded the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts (now the Foundation for Contemporary Arts), to raise funds in the performance field.[47] Johns continued his support of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, and served as an artistic adviser from 1967 to 1980. In 1968 Cunningham made a Duchamp-inspired theater piece, Walkaround Time, for which Johns's set design replicates elements of Duchamp's work The Large Glass (1915–23).[48] Earlier, Johns also wrote Neo-dada lyrics for The Druds, a short-lived avant-garde noise music art band that featured prominent members of the New York proto-conceptual art and minimal art community.[49][50] The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, owns Chuck Close's large-scale portrait of Johns.[51] In the late 1960s Johns' work was published in 0 to 9 magazine, an avant-garde journal which experimented with language and meaning-making

Commissions

[edit]In 1963, the architect Philip Johnson commissioned Johns to make a work for what is now the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center.[10] Numbers (1964), a 9-by-7-foot grid of numerals, debuted in 1964 and, after presiding over the theater's lobby for 35 years, was supposed to be sold by the center for a reported $15 million in 1979. Numbers is historically important because it is the largest work of the artist's Numbers motif, and each of its Sculp-metal and collage units is on a separate canvas.[10] Responding to widespread criticism, the board of Lincoln Center decided to drop its plans to sell the work, which was Johns's first and only public commission.[52]

Style

[edit]Johns's work is sometimes grouped with Neo-Dada and pop art: he uses symbols in the Dada tradition of the readymades of Marcel Duchamp, but unlike many pop artists such as Andy Warhol, he does not engage with celebrity culture.[53][30] Other scholars and museums position Johns and Rauschenberg as predecessors of pop art.[54][30]

Valuation and awards

[edit]In 1980 the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, paid $1 million for Three Flags (1958), then the highest price ever paid for the work of a living artist.[19] In 1988, Johns's False Start (1959) was sold at auction at Sotheby's to Samuel I. Newhouse Jr. for $17.05 million, setting a record at the time as the highest price paid for a work by a living artist at auction, and the second highest price paid for an artwork at auction in the U.S.[55] In 1998, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, bought Johns's White Flag (1955), the first painting by the artist to enter the Met's collection. While the museum would not disclose how much was paid, the New York Times reported that "experts estimate [the painting's] value at more than $20 million."[56] In 2006, Johns's False Start (1959) again made history. Private collectors Anne and Kenneth Griffin (founder of the Chicago-based hedge fund Citadel LLC) purchased the work from David Geffen for $80 million, making it the most expensive painting by a living artist.[19] In 2010, Flag (1958), was sold privately to hedge fund billionaire Steven A. Cohen for a reported $110 million (then £73 million; €81.7 million). The seller was Jean-Christophe Castelli, son of Leo Castelli, Johns's dealer, who had died in 1999. While the price was not disclosed by the parties, the New York Times reported that Cohen paid about $110 million.[57] On November 11, 2014, a 1983 version of Flag was auctioned at Sotheby's in New York for $36 million, establishing a new auction record for Johns.[58]

Johns has received many awards throughout his career. The sole honorary degree he has accepted is Honorary Degree of Doctor of Humane Letters, which the University of South Carolina conferred upon him in 1969. In 1984, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Boston.[59] In 1988, he received the highest honor at the 43rd Venice Biennale—the Golden Lion—for his exhibition in the United States pavilion. Johns was elected an Honorary Member of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1989.[60] In 1990, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts.[61] That year he was also elected an associate national academician of the National Academy of Design (now the National Academy Museum and School), rising to national academician in 1994.[62] In 1993, he received the Praemium Imperiale for painting, a lifetime achievement award from the Japan Art Association.[63] In 1994 he was awarded the Edward MacDowell Medal.[64] He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1973 and the American Philosophical Society in 2007. On February 15, 2011, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama, becoming the first painter or sculptor to receive a Presidential Medal of Freedom since Alexander Calder in 1977.[65]

In 2007, the National Gallery of Art acquired about 1,700 of Johns's prints. This made the gallery home to the largest number of Johns's works held by a single institution.

Selected work

[edit]- Flag (1954–55) view

- White Flag (1955) view

- Target with Plaster Casts (1955) view

- Tango (1955)

- Target with Four Faces (1955) view

- Three Flags (1958) view

- Numbers in Color (1958–59) view

- Device Circle (1959) view

- False Start (1959) view

- Coat Hanger (1960) view

- Painting with Two Balls (1960) view

- Painted Bronze (1960) view

- Painting with Ruler and 'Gray' (1960)

- Painting Bitten by a Man (1961) view

- The Critic Sees (1961) view

- Target (1961) view

- Map (1961) view

- Device (1961–62) view

- Study for Skin I (1962) view

- Diver (1962–63) view

- Periscope (Hart Crane) (1963) view

- Voice (1964/67) view

- Untitled (Skull) (1973) view

- Tantric Detail I, II, III (1980) view

- Usuyuki (1981) view

- Perilous Night (1982) view

- The Seasons (1987) view

- Green Angel (1990) view

- After Hans Holbein (1993) view

- Bridge (1997) view

- Regrets (2013) view

- Slice (2020) view

In popular culture

[edit]- In "Mom and Pop Art", a 1999 episode of the animated television series The Simpsons, Johns guest-stars as himself.[66] He is depicted as a thief who steals everyday objects such as lightbulbs. In The Diplomat, a 2023 Netflix series, Johns' painting Flag is pictured hanging on the wall of the US embassy (season 1, episodes 1 and 8). [67]

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ a b Solomon, Deborah (February 7, 2018). "Jasper Johns Still Doesn't Want to Explain His Art". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Stein, Judith (October 24, 2021). "Jasper Johns, master virtuoso of the double, one of the most influential of American painters, in massive Philly-NYC exhibition". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Horne, Peter; Lewis, Reina, eds. (1996). Outlooks: lesbian and gay sexualities and visual cultures. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 0-415-12468-9.

Rauschenberg, who was better known in 1963 than Warhol was, and Jasper Johns were both prototypical Pop artists as well as gay men; they also were lovers.

- ^ Small, Zachary (May 19, 2017). "Why Can't the Art World Embrace Robert Rauschenberg's Queer Community?". Artsy. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

After he and Weil divorced in 1953, Rauschenberg had a brief fling with Twombly, which subsequently led to a romance with his collaborator, Jasper Johns, from 1954 to 1961.

- ^ Stern, Mark Joseph (February 26, 2013). "Is MoMA Putting Artists Back in the Closet?". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns were lovers during this six-year period of collaboration, and their relationship had a profound impact on their art.

- ^ "Lifetime Honors: National Medal of Arts". National Endowment for the Arts. n.d. Archived from the original on January 20, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (March 18, 2010). "Planting a Johns 'Flag' in a Private Collection". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ Töniges, Sven (May 14, 2020). "The Flag painter: Jasper Johns turns 90". DW. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Bernstein, Roberta (2016). Jasper Johns Catalogue Raisonné of Painting and Sculpture, Volume 1. Wildenstein Plattner Institute. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-300-22742-0.

- ^ "Jasper Johns (b. 1930)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. May 4, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rosenthal, Nan (October 2004). "Jasper Johns (born 1930) In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "Gay Artist Robert Rauschenberg Dead at 82". The Advocate. May 14, 2008.

He met Jasper Johns in 1954. He and the younger artist, both destined to become world-famous, became lovers and influenced each other's work. According to the book Lives of the Great 20th Century Artists, Rauschenberg told biographer Calvin Tomkins that 'Jasper and I literally traded ideas. He would say, 'I've got a terrific idea for you,' and then I'd have to find one for him.'

- ^ Zongker, Brett (November 1, 2010). "Smithsonian explores impact of gays on art history". The Associated Press.

When artist Jasper Johns was mourning the end of his relationship with Robert Rauschenberg, he took one of his famous flag paintings, made it black, and dangled a fork and spoon together from the top. Hidden symbols in Johns' "In Memory of My Feelings," tell part of story, curators said. Color from the relationship is gone. A fork and spoon elsewhere in the painting are separated. Here we have a coded glimpse into a six-year relationship that was rarely acknowledged even in Rauschenberg's 2008 obituary. The Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery is decoding such history from abstract paintings and portraits in the first major museum exhibit to show how sexual orientation and gender identity have shaped American art.

- ^ Vaughan, David (July 27, 2009). "Obituary: Merce Cunningham". The Observer.

- ^ Lanchner, Carolyn; Johns, Jasper (2010). Jasper Johns. The Museum of Modern Art. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-87070-768-1.

- ^ "Leo Castelli to Paul Cummings, oral history interview with Leo Castelli, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, May 14, 1969". Archives of American Art. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Roberta (2016). Jasper Johns Catalogue Raisonné of Painting and Sculpture, Volume 5. Wildenstein Plattner Institute. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-300-22742-0.

- ^ a b c Vogel, Carol (February 3, 2008). "The Gray Areas of Jasper Johns". New York Times. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- ^ "Jasper Johns Plans to Turn His 170-Acre Estate Into an Artists' Retreat". Bloomberg.com. September 19, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ Cascone, Sarah (September 18, 2017). "Jasper Johns Plans to Turn His Bucolic Connecticut Home and Studio Into an Artists' Retreat". Artnet News. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c Crow, Thomas (2015). The Long March of Pop : Art, Music, and Design, 1930-1995. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-300-20397-4. OCLC 971188663.

- ^ a b c Johns, Jasper (1961). "Target". The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Durner, Leah (2004), Tymieniecka, Anna-Teresa (ed.), "Gestural Abstraction and the Fleshiness of Paint", Metamorphosis: Creative Imagination in Fine Arts Between Life-Projects and Human Aesthetic Aspirations, Analecta Husserliana, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 187–194, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-2643-0_14, ISBN 978-1-4020-2643-0, retrieved April 21, 2021

- ^ Stiles, Kristine; Selz, Peter (1996). Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists' Writings. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-520-20251-1.

- ^ Rutherfurd, Chanler (April 20, 2018). "The Story Behind Jasper Johns' American Flag & His Most Famous Print". Sotheby's.

Source cited: The Prints of Jasper Johns 1960 – 1993, A Catalogue Raisonné, introduction

- ^ Wallace, Isabelle Loring. "The incredible story behind Flag by Jasper Johns". Phaidon. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ "Flag - Jasper Johns". The Broad. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (October 24, 2008). "The truth beneath Jasper Johns' stars and stripes". The Guardian. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c Riefe, Jordan (February 21, 2018). "Why People Still Get Worked Up About Jasper Johns's 'Flag' Painting". Observer. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ "Jasper Johns. Target with Four Faces. 1955". The Museum of Modern Art. 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (February 2, 2007). "Bull's-Eyes and Body Parts: It's Theater, From Jasper Johns". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Macpherson, Amy (November 29, 2017). "Video: what is encaustic painting?". Royal Academy of Arts. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Edgers, Geoff. "How did this teenager's drawing wind up in a Jasper Johns painting at the Whitney?". Washington Post. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (September 13, 2021). "All the World in a 'Slice' of Art". The New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "The Complicated Story Behind Jasper Johns's Dispute with a Cameroonian Teen over a Drawing of a Knee (It Has a Happy Ending)". October 2021.

- ^ Genocchio, Benjamin (December 5, 2008). "In Jasper Johns's Hands, a Simple Object Glows". New York Times. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ "Jasper Johns: Numbers, 0–9, and 5 Postcards". Matthew Marks Gallery. 2012. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012.

- ^ "Jasper Johns: New Sculpture and Works on Paper". Matthew Marks Gallery. 2011. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "Jasper Johns". Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE). Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ "Jasper Johns". Gemini GEL. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ "Jasper Johns Usuyuki". Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 1981. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ "Foirades/Fizzles". Museum of Modern Art, New York. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ "Cup 2 Picasso, 1973". National Gallery of Art. n.d. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

Accession Number 2008.27.7

- ^ "Sun on Six by Jasper Johns on artnet Auctions". Artnet.com. May 12, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Carol Vogel (April 17, 2014), Art as Magazine Insert New York Times.

- ^ "Founders". foundationforcontemporaryarts.org. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ Alistair Macaulay (January 7, 2013), Cunningham and Johns: Rare Glimpses Into a Collaboration New York Times.

- ^ [1] Patty Mucha on The Druds

- ^ Blake Gopnik, Warhol: A Life as Art London: Allen Lane. March 5, 2020. ISBN 978-0-241-00338-1 p. 297

- ^ "Jasper, 1997-98". nga.gov.uk. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ^ Carol Vogel (January 26, 1999), Lincoln Center Drops Plan to Sell Its Jasper Johns Painting New York Times.

- ^ Tate. "Neo-dada – Art Term". Tate [Museum]. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ "Neo-Dada". The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

The term Neo-Dada, first popularized in a group of articles by Barbara Rose in the early 1960s, has been applied to a wide variety of artistic works, including the pre-Pop Combines and assemblages of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns ...

- ^ RITA REIFPublished: November 11, 1988 (November 11, 1988). "Jasper Johns Painting Is Sold for $17 Million – New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Vogel, Carol (October 29, 1998). "Met Buys Its First Painting by Jasper Johns". New York Times. Retrieved February 28, 2008.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (March 18, 2010). "Planting a Johns 'Flag' in a Private Collection". New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Rothko, Jasper Johns star at NYC art auction". businessweek.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "Jasper Johns". American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Jasper Johns | Artist | Royal Academy of Arts". Royal Academy of Arts. Archived from the original on February 9, 2024.

- ^ "National Medal of Arts". The National Endowment for the Arts. April 24, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ "Jasper Johns". National Academy of Design. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Jasper Johns". Praemium Imperiale. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Jasper Johns". MacDowell. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Jasper Johns to be awarded Presidential Medal of Freedom". artforum.com. February 14, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ ""The Simpsons" Mom and Pop Art (TV Episode 1999)" – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ Cahn, Debora (director) (2023). The Diplomat ["S1 E1: "The Cinderella Thing"] (television). USA: Netflix.

- Further reading

- Basualdo, Carlos, and Scott Rothkopf. Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art; Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2021.

- Bernstein, Roberta. Jasper Johns' Paintings and Sculptures, 1954–1974: "The Changing Focus of the Eye." Studies in the Fine Arts: The Avant-Garde 46. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1985.

- Bernstein, Roberta. Jasper Johns: Catalogue Raisonné of Painting and Sculpture. 5 Volumes. New York: Wildenstein Plattner Institute, 2016.

- Bernstein, Roberta. Jasper Johns: Redo an Eye. New York: Wildenstein Plattner Institute, 2017.

- Bernstein, Roberta, Edith Devaney, et al. Jasper Johns. London: Royal Academy of Arts; Los Angeles, Broad, 2017.

- Busch, Julia M. A Decade of Sculpture: The New Media in the 1960s. Philadelphia: Art Alliance Press, 1974.

- Castleman, Riva. Jasper Johns: A Print Retrospective. New York: Museum of Modern Art 1986.

- Crichton, Michael. Jasper Johns. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994. Revised and expanded edition of the 1977 Whitney Museum exhibition catalogue.

- Dacherman, Susan, and Jennifer L. Roberts.Jasper Johns: Catalogue Raisonné of Monotypes. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017.

- Field, Richard. The Prints of Jasper Johns: 1960–1993; A Catalogue Raisonné. West Islip, NY: Universal Limited Art Editions, 1994.

- Hess, Barbara. Jasper Johns. The Business of the Eye. Translated by John William Gabriel. Basic Art Series. Cologne: Taschen, 2007.

- Jasper Johns: Catalogue Raisonné of Drawing. 6 volumes. Houston: Menil Collection, 2018.

- Kozloff, Max. Jasper Johns. Meridian Modern Artists Series. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1972. (out of print)

- Krauss, Rosalind E. '"Split Decisions: Jasper Johns in Retrospect; Whole in Two." Artforum, 35, no. 1 (September 1996): 78–85, 125. Findarticles.com

- Kuspit, Donald. "Jasper Johns: The Graying of Modernism." In Psychodrama: Modern Art as Group Therapy, 417–425. London: Ziggurat, 2010.

- Orton, Fred. Figuring Jasper Johns. Essays in Art and Culture. London: Reaktion Books, 1994.

- Rondeau, James, and Douglas Druick. Jasper Johns: Gray. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Rosenberg, Harold. "Jasper Johns: 'Things the Mind Already Knows'". Vogue, February 1964, 174–77, 201, 203.

- Shapiro, David. Jasper Johns Drawings, 1954–1984. Edited by Christopher Sweet. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1984 (out of print).

- Steinberg, Leo. Jasper Johns. New York: George Wittenborn, 1963. Revised and expanded as "Jasper Johns: The First Seven Years of His Art." In Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art, 17–54. New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.

- Tomkins, Calvin. Off the Wall: Portrait of Robert Rauschenberg. New York: Picador, 2005.

- Varnedoe, Kirk, ed. Jasper Johns: Writings, Sketchbook Notes, Interviews. Compiled by Christel Hollevoet. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1996.

- Varnedoe, Kirk, Roberta Bernstein, and Lilian Tone. Jasper Johns: A Retrospective. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1996.

- Weiss, Jeffrey. Jasper Johns: An Allegory of Painting, 1955–1965. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Yau, John. A Thing Among Things: The Art of Jasper Johns. New York: D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2008.ISBN 9781933045627

External links

[edit]- Jasper Johns: An Allegory of Painting, 1955–1965, an exhibition at the US National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

- States and Variations: Prints by Jasper Johns, an exhibition at the US National Gallery of Art

- Jasper Johns (born 1930) Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Jasper Johns at the Museum of Modern Art

- Jasper Johns bio at artchive.com

- PBS Jasper Johns 2008

- Jasper Johns at IMDb

- Jasper Johns discography at Discogs

- Powers Art Center - A Showcase of Jasper Johns's Works on Paper

- Jasper Johns's Three Flags at Art Beyond Sight (Art Education for the Blind)

- Review of the Whitney and the Philadelphia museums' 2021 shows at Artnet News, October 12, 2021

- The Formulaic Juxtapositions of Jasper Johns's 'Mind/Mirror', at Frieze, November 12, 2021

- Jasper Johns

- 1930 births

- Living people

- People from Augusta, Georgia

- People from Allendale, South Carolina

- 20th-century American painters

- American male painters

- 21st-century American painters

- 21st-century American male artists

- American pop artists

- Artists from New York (state)

- Artists from South Carolina

- University of South Carolina alumni

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- American gay artists

- American LGBTQ painters

- Gay painters

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- National Academy of Design members

- Parsons School of Design alumni

- American postmodern artists

- Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- Wolf Prize in Arts laureates

- People from Stony Point, New York

- 20th-century American printmakers

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Honorary members of the Royal Academy

- Painters from Georgia (U.S. state)

- 20th-century American male artists

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts

- 20th-century American LGBTQ people

- 21st-century American LGBTQ people