Salmas

Salmas

سلماس | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Salmas | |

| |

| Coordinates: 38°12′10″N 44°46′01″E / 38.20278°N 44.76694°E[1] | |

| Country | Iran |

| Province | West Azerbaijan |

| County | Salmas |

| District | Central |

| Earliest Recognition | 224–242 AD |

| Rebuilt | 1930 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Body | Salmas |

| • Mayor | N/A |

| Area | |

• Total | 9.26 sq mi (24.0 km2) |

| • Land | 9.26 sq mi (24.0 km2) |

| • Water | 0 sq mi (0 km2) |

| • Metro | 4.75 sq mi (12.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 4,532 ft (1,381 m) |

| Population (2016)[2] | |

• Total | 92,811 |

| • Rank | TBA, Iran |

| • Density | 10,000/sq mi (3,900/km2) |

| Demonym(s) | Salmasi, Salmassi |

| Time zone | UTC+3:30 (IRST) |

| ZIP code | 58811 ≤ 58XXX ≤ 58991 |

| Area code | 44 |

Salmas (Persian: سلماس)[a] is a city in the Central District of Salmas County, West Azerbaijan province, Iran, serving as capital of both the county and the district.[5] It is northwest of Lake Urmia, near Turkey.[6]

Etymology

[edit]The original name of Salmas was Dilman, which is probably related to the Daylamites who sometimes controlled the region. In the 20th-century, it was known as Shapur.[7]

History

[edit]

Salmas is located in the historic Azerbaijan region.[7] Its archaeological relics, which date as far back as the Urartian kingdom (860 BC–590 BC), attest to its long human habitation.[7] Salmas was part of the Armenian province of Nor Shirakan (also known as Persarmenia),[7][8] which was inhabited by Armenians.[8] A rock relief erected during the reign of the Sasanian monarch Ardashir I (r. 224–242) is located in the Khan-Takhti village near Salmas. This rock relief illustrates two akin scenarios in which a standing man receives a ring from a man riding a horse.[9]

The standing men's names are subject to interpretation, but the horsemen are typically considered to be Ardashir I and his son and heir, Shapur I. The German orientalist Ferdinand Justi (died 1907) theorized that the relief is meant to show the Armenians' gratitude to Ardashir I and Shapur I, something which some later scholars supported. The Iranologist Ehsan Shavarebi considers this theory to be "logical" but stresses that "we need more investigations on the event depicted on the relief." He suggests that the rock relief is meant to illustrate the probable peace made between Ardashir I and the Kingdom of Armenia.[9] When the Arsacid house of Armenia was abolished and the country was made a Sasanian province in 428, Nor Shirakan and Paytakaran were incorporated into the Sasanian province of Adurbadagan.[10]

Two archeological sites showing inhabitation during the Sasanian era has been found near Salmas. One of them is known as Haftan Tepe, which contains Sasanian-era pottery akin to those found in Takht-e Soleyman. The other is called Qazun Basi, located to the south of Salmas. They were likely used as military and administrative hubs.[11] The 9th-century Muslim historian al-Baladhuri reported that the taxes of Salmas had been long given to Mosul, suggesting that during the Arab conquest of Iran it was Arab armies from Diyar Rabi'a that conquered Salmas. During the reign of Marzuban ibn Muhammad (r. 941/42–957) of the Daylamite Sallarid dynasty, Salmas became subjugated to his rule. In 943/44, Marzuban ibn Muhammad repelled an attack on Salmas by the Hamdanid dynasty, and in 955/56, it was attacked by the Kurdish military leader Daysam.[7] By 975, Salmas was seemingly under the rule of the Kurdish Rawadid dynasty, who after 983/84 ruled all of Azerbaijan.[12]

Salmas is described by the 10th-century Islamic geographers Ibn Hawkal and al-Istakhri as a tiny town in Azerbaijan with a sturdy wall in a fertile location. Another 10th-century Islamic geographer, al-Maqdisi, considers the town to have been part of the administration of Armenia and inhabited by Kurds, which according to the modern scholar and orientalist Clifford Edmund Bosworth must had been part of the Hadhabani tribe.[7] In 1054/55, the Seljuk Empire imposed their rule on the Rawwadids, and in 1070 removed them from power resulting in Salmas being captured by the Seljuks.[12] In 1064, the Seljuk sultan Alp Arslan (r. 1063–1072) made a military campaign against the Byzantines, Armenians and Georgians, in which the Kurds of Salmas took part.[7]

Salmas was in ruins during the lifetime of the Muslim scholar Yaqut al-Hamawi (died 1229), but according to the geographer Hamdallah Mustawfi (died after 1339/40), it was once again thriving in the middle of the 14th-century. The vizier Khwaja Taj al-Din Ali Shah Tabrizi had rebuilt the town's 8,000-steps long wall during the reign of Ilkhanate ruler Ghazan (r. 1295–1304), and Salmas's revenues—presumably those of the entire district—amounted to 39,000 dinars, a large amount.[7]

Another mention of the city was made in 1281, when its Assyrian bishop made the trip to the consecration of the Assyrian Church of the East patriarch Yaballaha in Baghdad.[13]

In the Battle of Salmas on 17–18 September 1429, the Kara Koyunlu were defeated by Shah Rukh who was consolidating Timurid holdings west of Lake Urmia.[14] However, the area was retaken by the Kara Koyunlu in 1447 after the death of Shah Rukh.

The Lak tribe settled in the Salmas area at the end of the 16th century. It seems that at the time, the governor of Lak and Salmas was interchangeable. Today, there remains a possible final trace of the tribe in the form of a Lakestan area of the tribe which post-Safavids lived dispersed across the country.[15]

In March 1915 Cevdet Bey ordered 800 Assyrians of Salmas to be killed.[16] Mar Shimun, the Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East was murdered by the Kurdish chieftain Simko Shikak in Salmas in March 1918.[17][18][19]

Around the advent of the 1910s, Imperial Russia started to station infantry and Cossacks in Salmas.[20] The Russians retreated at the time of Enver Pasha's offensive in the Iran-Caucasus region, but returned in early 1916, and stayed up to the wake of the Russian Revolution.[20]

Demographics

[edit]Language and ethnicity

[edit]The majority of the population is composed of Azerbaijanis and Kurds[21] with some Armenians, Assyrians, and Jews.[22]

Population

[edit]At the time of the 2006 National Census, the city's population was 79,560 in 19,806 households.[23] The following census in 2011 counted 88,196 people in 23,751 households.[24] The 2016 census measured the population of the city as 92,811 people in 27,115 households.[2] According to the 2019 census, the city's population is 127,864.[25]

Geography

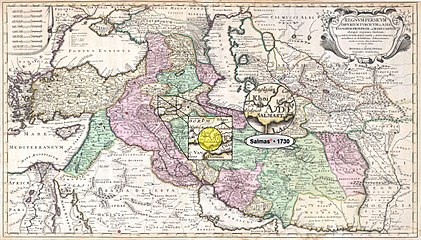

[edit]Salmas in early atlases

[edit]The atlases below are some of the earliest maps to have been ever sketched to show the territory and originality of the name of Salmas and are some of the strongest documents providing proofs to some basic facts about the city including its existence and identity.

-

Salmas in 1724[26] Homann Map of "Persian Empire" at the Time of Safavid dynasty • Modified by Hassan Jahangiri

-

Salmas in 1730 Reiner and Joshua Ottens Map of the "Persian Empire" at the Time of Safavid dynasty • Modified by Hassan Jahangiri

-

Salmas in 1747 Bowen Map of the "Persian Empire" at the Time of Afsharid dynasty • Modified by Hassan Jahangiri

-

Salmas in 1814 Thomson Map of the "Persian Empire" at the Time of Qajar dynasty • Modified by Hassan Jahangiri

-

Salmas in 1818 Pinkerton Map of "Turkey in Asia, Iraq, Syria, and Palestine" (Concurred with the Time of Qajar dynasty) • Modified by Hassan Jahangiri

Climate

[edit]Under the Köppen climate classification, Salmas features a cold semi-arid climate (BSk), typical of northwestern Iran.

| Climate data for Salmas (2001-2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

12.1 (53.8) |

16.6 (61.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

28.2 (82.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.5 (88.7) |

26.9 (80.4) |

20.6 (69.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

4.8 (40.6) |

17.8 (64.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.7 (27.1) |

0.5 (32.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

11.5 (52.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −7.5 (18.5) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

0.3 (32.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

11.7 (53.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

5.1 (41.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 10.3 (0.41) |

16.8 (0.66) |

29.9 (1.18) |

43.9 (1.73) |

46.0 (1.81) |

20.7 (0.81) |

8.0 (0.31) |

8.1 (0.32) |

9.9 (0.39) |

22.6 (0.89) |

21.5 (0.85) |

9.8 (0.39) |

247.5 (9.75) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 69 | 58 | 56 | 58 | 45 | 43 | 40 | 42 | 52 | 68 | 76 | 57 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | −5.8 (21.6) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

6.2 (43.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

5.8 (42.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

2.3 (36.2) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 139.0 | 168.4 | 214.7 | 214.0 | 245.3 | 347.4 | 354.4 | 348.4 | 305.8 | 240.0 | 174.3 | 137.8 | 2,889.5 |

| Source: Iran Meteorological Organization(temperatures[27]), (precipitaion[28]), (humidity, dew point and sun 2001-2005[29][30]) | |||||||||||||

| Year | Population | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 | ~8000 | — |

| 1934 | ~7000 | — |

| 1956 | 13,161 | — |

| 1966 | 21,703 | +64.9% |

| 1976 | 27,638 | +27.3% |

| 1986 | 50,573 | +83.0% |

| 1996 | 65,416 | +29.3% |

| 2006 | 89,617 | +37.0% |

| 2011 | 97,060 | +8.3% |

| 2016 | 101,441 | +4.5% |

| 2021 | N/A | — |

| Note: The data presented of 1976 and earlier (1956–1976) are from the censuses before Iranian Revolution and the data of 1986 and later (1986–2016) are from the censuses after it. The data for the years 1920 and 1924 are not of any censuses. Sources: "Population and Housing Census". Statistical Center of Iran. (used for censuses of 2006 and later), "An Analysis to the Urban System of West Azerbaijan Province During the Years 1956 till 2006". Urban Ecology Researches. (used for censuses of 1996 and earlier; the amounts are obtained from the data given in "Real Population" columns!), "Location and Geography of the City". Salmas County Municipality.[permanent dead link] (used for data of the years 1920 and 1924) | ||

Notable people

[edit]- Stepanos V of Salmast (d. 1567) – Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church

- Yohannan Gabriel (1758–1833) – Chaldean Catholic bishop of Salmas

- Nicholas I Zaya (d. 1855) – Patriarch of Babylon of the Chaldeans

- Raffi (1835–1888) – Armenian novelist

- Paul Bedjan (1838–1920) – Chaldean Catholic priest and orientalist

- Abraham Guloyan (1893–1983) – Politician

- Murad Kostanyan (1902–1989) – Actor

- Hossein Sadaghiani (1903-1982) - The first ever manager and head coach of Iran national football team (1941-1951) and the first ever Iranian soccer player to play for foreign clubs (R. Charleroi S.C. and Fenerbahce SK) and in a European league

- Ardeshir Ovanessian (c. 1905–1990) – Communist leader

- Timur Lakestani (1915–2011) – aka Father of Iranian Electrical Industry

- Jafar Salmasi (1918–2000) – weightlifter

- Emmanuel Agassi (1930–2021) – boxer and father of Andre Agassi

- Hadi Asghari (b. 1981) – football player

Gallery

[edit]-

Overall View of Imam St. and Shahrdari Sq.

-

Islamic Republic Blvd., Near Panahi Technical School

-

Khan Takhti-Rd near Salmas

-

The Haftvan Church

-

Chaldean Catholic Church in Salmas

-

Salmas

-

An angled front view of Salmas Imam Khomeini Prayer House, 2017

-

A view of Nation Park in a Winter night, 2016

See also

[edit]![]() Media related to Salmas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Salmas at Wikimedia Commons

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ OpenStreetMap contributors (27 September 2024). "Salmas, Salmas County" (Map). OpenStreetMap (in Persian). Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ a b Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1395 (2016): West Azerbaijan Province. amar.org.ir (Report) (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Salmas can be found at GEOnet Names Server, at this link, by opening the Advanced Search box, entering "-3082081" in the "Unique Feature Id" form, and clicking on "Search Database".

- ^ "List of all entries". Assyrian Languages. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Habibi, Hassan (c. 2023) [Approved 21 June 1369]. Approval of the organization and chain of citizenship of the elements and units of the national divisions of West Azerbaijan province, centered in the city of Urmia. lamtakam.com (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Defense Political Commission of the Government Council. Notification 82808/T137. Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 20 December 2023 – via Lam ta Kam.

- ^ Bosworth, C. E. (2012). "Salmās". Encyclopedia of Islam. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_6560.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bosworth 1995.

- ^ a b Ghodrat-Dizaji 2010, p. 75.

- ^ a b Shavarebi 2014, p. 115.

- ^ Shahinyan 2016, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Ghodrat-Dizaji 2007, p. 90.

- ^ a b Peacock 2017.

- ^ Houtsma, M. Th. et al. (1993 reprint) "Salmas" E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936 Volume 4, E.J. Brill, New York, page 118, ISBN 90-04-09796-1

- ^ Houtsma, M. Th. et al. (1993 reprint) "Tabrīz" E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936 Volume 4, E.J. Brill, New York, page 588, ISBN 90-04-09796-1

- ^ Naṣīrī, ʻAlī Naqī; Floor, Willem M. (2008). Titles & emoluments in Safavid Iran: a third manual of Safavid administration. Washington, DC: Mage Publishers. pp. 270–71. ISBN 978-1-933823-23-2. OCLC 183928765.

- ^ Yuhanon, B. Beth (30 April 2018). "The Methods of Killing in the Assyrian Genocide". Sayfo 1915. Gorgias Press. p. 183. doi:10.31826/9781463239961-013. ISBN 978-1-4632-3996-1. S2CID 198820452.

- ^ Brill, E. J. (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936. S - Ṭaiba. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-09793-3.

- ^ O'Shea, Maria T. (2004) "Trapped Between the Map and Reality: Geography and Perceptions of Kurdistan Routledge, New York, page 100, ISBN 0-415-94766-9

- ^ Nisan, Mordechai (2002) Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle and Self-Expression (2nd edition) McFarland, Jefferson, North Carolina, page 187, ISBN 0-7864-1375-1

- ^ a b Atabaki 2006, p. 70.

- ^ "..:: شهرداری سلماس ::". Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ http://thegraduatesocietyla.org/images/author-padia-others.pdf Archived 12 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1385 (2006): West Azerbaijan Province. amar.org.ir (Report) (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1390 (2011): West Azerbaijan Province. irandataportal.syr.edu (Report) (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 20 January 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2022 – via Iran Data Portal, Syracuse University.

- ^ "2016 Population and Housing Census". Statistical Center of Iran. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ "Imperii Persici in omnes suas provincias nova tabula geographica". Library of Congress. January 1724.

- ^ "Form 5: AVERAGE OF MEAN DAILY TEMPERATURE IN C. Station: Salmas(40722)". Chaharmahalmet. Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 22 November 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- "Form 2: AVERAGE OF MINIMUM TEMPERATURE IN C. Station: Salmas(40722)". Chaharmahalmet. Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- "Form 3: AVERAGE OF MAXIMUM TEMPERATURE IN C. Station: Salmas(40722)". Chaharmahalmet. Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "Form 25: Monthly total of precipitation in mm. Station: Salmas(40722)". Chaharmahalmet. Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "Form 14: AVERAGE OF RELATIVE HUMIDITY IN PERCENT Station: Salmas(40722)". Chaharmahalmet. Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- "Form 10: AVERAGE OF DEW POINT TEMPERATURE IN C. Station: Salmas(40722)". Chaharmahalmet. Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "Form 42: Monthly total of sunshine hours Station: Salmas(40722)". Chaharmahalmet. Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Atabaki, Touraj (2006). Iran and the First World War: Battleground of the Great Powers. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1860649646.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1995). "Salmās". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Ghodrat-Dizaji, Mehrdad (2007). "Administrative Geography of the Early Sasanian Period: The Case of Ādurbādagān". Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 45 (1): 87–93. doi:10.1080/05786967.2007.11864720. S2CID 133088896.

- Ghodrat-Dizaji, Mehrdad (2010). "Ādurbādagān during the Late Sasanian Period: A Study in Administrative Geography". Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 48 (1): 69–80. doi:10.1080/05786967.2010.11864774. S2CID 163839498.

- Peacock, Andrew (2017). "Rawwadids". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shahinyan, Arsen (2016). "Northern Territories of the Sasanian Atropatene and the Arab Azerbaijan". Iran and the Caucasus. 20 (2): 191–203. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20160203.

- Shavarebi, Ehsan (2014). "A Reinterpretation of the Sasanian Relief at Salmās". Iran and the Caucasus. 18 (2). Brill: 115–133. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20140203.

External links

[edit]

![Salmas in 1724[26] Homann Map of "Persian Empire" at the Time of Safavid dynasty • Modified by Hassan Jahangiri](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7c/Salmas_in_Circa1700-Circa1720_Homann_Map_of_%22Persian_Empire%22_-_Jomann_Imperium_Periscum.jpg/281px-Salmas_in_Circa1700-Circa1720_Homann_Map_of_%22Persian_Empire%22_-_Jomann_Imperium_Periscum.jpg)