Die Freundin

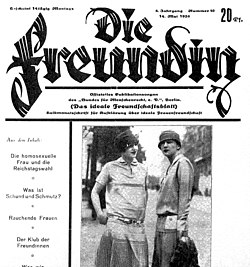

An issue of Die Freundin (May 1928) | |

| Categories | Lesbian magazine |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Friedrich Radszuweit |

| First issue | 8 August 1924 |

| Final issue | 8 March 1933 |

| Country | Germany |

| Based in | Berlin |

| Language | German |

Die Freundin (English: "The Girlfriend")[1][2] was a popular Weimar-era German lesbian magazine[3] published from 1924 to 1933.[4][5] Founded in 1924, it was the world's first lesbian magazine, closely followed by Frauenliebe and Die BIF (both 1926). The magazine was published from Berlin, the capital of Germany, by the Bund für Menschenrecht (translated variously as League for Human Rights or Federation for Human Rights and abbreviated as BfM), run by gay activist and publisher Friedrich Radszuweit.[4][6] The Bund was an organization for homosexuals which had a membership of 48,000 in the 1920s.[4]

Die Freundin and other lesbian magazines of that era such as Frauenliebe (Love of Women) represented a part-educational and part-political perspective, and they were assimilated with the local culture.[7] Die Freundin published short stories and novellas.[3] Renowned contributors were pioneers of the lesbian movement like Selli Engler or Lotte Hahm. The magazine also published advertisements of lesbian nightspots, and women could place their personal advertisements for meeting other lesbians.[4] Women's groups related to the Bund für Menschenrecht and Die Freundin offered a culture of readings, performances, and discussions, which was an alternative to the culture of bars. This magazine was usually critical of women for what they viewed as "attending only to pleasure", with a 1929 article urging women: "Don't go to your entertainments while thousands of our sisters mourn their lives in gloomy despair."[6]

Die Freundin, along with other gay and lesbian periodicals, was shut down by the Nazis after they came to power in 1933. But even before the rise of the Nazis, the magazine faced legal troubles during the Weimar Republic. From 1928 to 1929, the magazine was shut down by the government under a law that was supposed to protect youth from "trashy and obscene" literature. During these years, the magazine operated under the title Ledige Frauen (Single Women).[6]

Publication dates

[edit]Die Freundin appeared from 1924 to 1933 in Berlin, distributed by BfM. It was a joint federation of the BfM and Bundes für Ideale Frauenfreundschaft (translated to "Covenant for Women's Friendships").[8] It was initially located in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Strasse 1 in Berlin-Pankow in 1925.[9] As early as 1927,[10] it had a branch office in the Neue Jakobstraße 9 in Berlin-Mitte, which according to the data of 1932[11] was staffed between 9am-6pm.

Die Freundin was available in major retailers across all of Germany and Austria.[8] Additionally, street vendors and magazine dealers in Berlin sold the publication at a price of 30 Pfennig in 1924–1925;[12] then the price rose to 20 Pfennig. Certain issues aimed to highlight the political importance of lesbian culture by printing phrases on the cover, such as "this magazine may be publicized everywhere!" In addition to sales revenues and those from the advertising business, editorial staff and subscribers also asked for donations.[8]

Though the exact circulation of Die Freundin is unknown, it is assumed that it was the most widely spread lesbian magazine of the Weimar Republic, with circulation well above that of every other lesbian magazine in the German-speaking world until the 1980s.[13] Thus, its circulation was likely much more than 10,000 copies, the print run of similar publication Frauenliebe in 1930.[14]

History of editions

[edit]After the first two editions of Die Freundin were published as inserts in Blätter für Menschenrechte (on 8 August 1924 and 12 September 1924), the following editions were published as separate publications, each between 8 and 12 pages. Die Freundin was thereafter the "first new independent magazine of the Radszuweit publishing house".[15] In 1925 it was suggested that Die Freundin should increase its page count (up to 20 pages)[15] as well as its price point to 50 Pfennig, but the attempt failed and the old format remained. Already the first issue contained an insert titled Der Transvestit, which kept on reappearing in future editions.[8] Until 1926, Die Freundin was also an insert inside of the memorandum of the Scientific Humanitarian Committee about Magnus Hirschfeld.[16]

The publication rhythm changed: in the first year it came out as a monthly magazine; from 1925 it appeared every two weeks and later even weekly.[8] The editions of 1928 were published on Mondays,[17] then later covers from 1932 show that it was published on Wednesdays.[11]

In 1926, there was no independent edition of Die Freundin; instead it appeared only as an insert inside the publication Freundschaftblatt. The reason for this irregularity is unknown.[12] Between June 1928 and July 1929, publication halted. After enactment of the law on the protection of young people from sabotage and trafficking, retailers were no longer allowed to sell lesbian magazines. The publisher opted for the temporary cessation of the magazine and instead started a new publication called Ledige Frauen, which made it to a total of 26 issues. The publisher explicitly deemed this a substitute to Die Freundin and saw the editions of 1929 as a continuation, giving it the subtitle Freundin as a reference. From July 1929, Die Freundin resumed its production.[12] In March 1931, Die Freundin was once again a victim of the "Schund-und-Schmutz" ("plague and filth") law, this time without a replacement.[15]

On 8 March 1933, the last issue of Die Freundin was published as the 10th edition of the 9th year. Like all gay and lesbian periodicals, it was banned as "degenerate" and legally had to cease production.[8]

Target groups

[edit]Die Freundin focused mainly on lesbian women, but also included inserts and editorial contributions on trans issues. The advertisements were also targeted at gay men and heterosexuals.[8]

Through its regular reports, advertisements and events related to the lesbian subculture of Berlin, it functioned similarly to a local newspaper. Readers of Die Freundin were, above all, professional modern women who lived independently.[8]

Editors and authors

[edit]It is nearly impossible today to trace back who exactly performed which editorial roles.[16] In the beginning Aenne Weber was the chief editor, who was also the first chairwoman of the women's chapter of BfM from 1924 to 1925.[18] In 1926, when the magazine was an insert within Freundschaftsblatt, the job went to Irene von Behlau. In 1927, Elisabeth Killmer became chief editor, and from 1928 to 1930 it was Bruno Balz. He was followed by Martin Radszuweit as the chief editor from 1930 onward.[15]

At this point, editorial teams were shared between the publications Blättern für Menschenrecht and Freundschaftsblatt, which is why certain articles were reprinted several times over the years, some deliberately abridged. These editorial articles were mostly written by men, usually by Friedrich Radszuweit, Paul Weber or Bruno Balz. Even articles on the activity of the association or about current political developments were, almost without exception, written by men. How this overwhelming presence of male voices in a magazine for lesbian women was seen by these women, whether editors or authors, was not spoken about.[15]

Die Freundin was aimed mainly at gay women, but was not written exclusively by them. There was a relatively high fluctuation among the authors.[8] Probably the most famous regular author was Ruth Margarete Roellig, who joined in 1927.[19] She was not only an author of the well-known book of Berlins lesbische Frauen (1928), a contemporary guide through the lesbian subculture of Berlin,[19] but had also been trained as an editor in 1911 and was thus one of the few professional writers. Other prominent authors were activists such as Selli Engler and Lotte Hahm.[8]

The writing of Die Freundin was specifically not reserved for any fixed writer. Already in 1925, the editorial staff solicited readers to submit their own writing. In 1927, the editors changed the structure of the magazine to motivate the readers to participate actively. In sections such as "Letters for Die Freundin" or "Our readers have the word", readers were able to share their lesbian self-image and experiences. Today, these reports are valuable documents on the life of lesbian women in German-speaking countries at this time.[8] In a 1932 advertisement, the editors explained in this sense that every "reader can send us manuscripts, we are glad when our readers participate in the magazine since it is published for them".[20]

Structure of the magazine

[edit]The layout of the magazine was simple and remained almost the same throughout the entire print run: the cover page came first, followed by the editorial section which didn't have any particular order. At the back of the magazine appeared one or two pages of the classifieds section.

Cover

[edit]Apart from the very first editions, which began directly with editorial writing, photographs of women (sometimes nude) were often found on the cover page - sometimes at the request of the readership.[21] The magazine's contents or poems were also frequently included on the cover.

Editorial structure

[edit]The two-column editorial section consisted equally of short stories, news, op-eds, poems, press reviews, and letters to the editor.[15] Small advertisements were scattered throughout the magazine, but there is no record of any illustrations being included.

Non-fiction: content and politics

[edit]In each issue, Die Freundin offered several articles on a variety of subject matters, including but not limited to historical issues relating to the history of lesbians; everyday problems of lesbian women in Germany; and cultural, scientific, or medical articles related to homosexuality. There were also contributions to literary themes and the Berlin social life in general.[8][5]

At times the magazine included an insert of Der Transvestit, but occasionally this part was simply integrated into the magazine under the subject area of trans issues.[8][5]

Homosexuality

[edit]As one of the first and most popular media of the early gay and lesbian movement, Die Freundin offered a space for discussing basic questions of lesbian identity. An important point of reference were articles and opinions oriented to the sexual-scientific authority of the time, Magnus Hirschfeld, and to his scientific-humanitarian committee "Wissenschaftlich-humanitären Komitee" or WhK. Their publications were often cited and praised, and in the first two years, the WhK's memos were featured in Die Freundin.[8]

A 1929 text called "The Love of The Third Sex" by Johanna Elberskirchen was shortened and featured in Die Freundin under the title "What Is Homosexuality?" It featured the idea that homosexuality is an innate, natural predisposition and that gay people formed a "third sex". This indicates that the philosophy of Die Freundin was in tandem with the current sexual-scientific theories of the time. This recognition of the "naturalness" of homosexuality led to the conclusion that gay people, including lesbian women, were entitled to full social recognition.[8]

By 1930, the magazine was repeatedly in disagreement with Magnus Hirschfeld. Hirschfeld was criticized for frequently condemning homosexuality as inferior or abnormal, or misrepresenting gay people in court proceedings, and thus contributing to their stigmatization.[13]

Lesbian identity

[edit]In spite of the participation of men and the broad array of themes, Die Freundin was a medium in which lesbian women found the necessary space to debate and define their sense of self, their roles in society, and their goals.

The thesis of the "third sex", which argued that the third sex be equal to the two heterosexual sexes, gained traction. A controversial discussion, which focused on the relationship between gay and bisexual women, was published in one of the issues. More or less unanimously, the discussion culminated in allegations that bisexual women were "vicious" and "perverse" which resulted in strongly-worded letters from readers who plead "hands off the bodies who enjoy both sexes for lust!", "they kick our love into the dirt!" and "this committee of women should be fought by gay women". The reason bisexual women were not recognized came from the fashionable understanding of homosexuality as biologically clearly defined, which was threatened by the apparent ambiguity of bisexual life styles.[13]

The widespread dichotomy of "masculine" vs. "feminine" lesbians (similar to today's butch and femme role distribution) then lead to discussions about the extent to which such roles continued to promote and reinforce stereotypes, which in the context the emerging women's movement was an important contribution.[13]

"Transvestite" identity

[edit]Between 1924 and 1933, the magazine issues a column titled Die Welt der Transvestiten ("The World of the Transvestites") featuring news about cross-dressing, letters written by transvestites, and reports of events of relevance to cross-dressers.[22] For example, when the Bund für Menschenrecht set up a transvestite support group called "The Coalition of the Transvestites" (Zusammenschluss der Transvestiten), Lina Es explained its goals in this column;[23] the same year, she wrote about police and the cross-dressers ("Die Transvestiten und die Polizei").[24] In 1929, a cross-dresser from Essen called Toni Simon wrote a letter recounting her trial for "grober Unfug" (disturbance of the public peace, because she cross-dressed in public) to which she went dressed as a woman. She was fined 100 Reichsmarks.[25]

The Women's Movement

[edit]Die Freundin's general texts on the women's movement were found very sporadically.[8] Die Freundin did not draw a specific alliance with the women's movement at the time, even though in 1924 the magazine claimed it would "advocate equal rights for women in social life". None of the subjects of the women's movement that were being discussed at that time were covered in the magazine, whether it was birth control, abortion, family or divorce law. Instead, the experience of gay women was prioritized, even if a topic such as the demand for equal representation could have been linked to existing issues of the women's movement.[12]

Allegedly, gender-specific experiences of women were neither accepted as submissions nor considered as attributions. If they were accepted, it was only in connection to the goal of gay women to achieve equality. Here, again, there is an emphasis on not being categorized within the dichotomy of a man-woman world, but rather being attributed to a separate sex.[12]

Gay politics

[edit]A central theme of Die Freundin was always the social and political obstacles that gay women faced. Despite the vivacity of the gay and lesbian life in the Berlin of the Weimar Republic, the lesbian lifestyle was not accepted by society. Throughout the publication's history, this was always the reason for including current political texts, whether reports and analyses of social and political conditions as far as they concerned gay people, or even calls-to-action. The readership didn't seem to be very animated by these attempts.[8][5]

The rootedness of Die Freundin in a male-dominated association led to regular publications of calls for the abolition of § 175. This did not concern gay women directly, because only male same-sex behaviour was covered by § 175. Again and again, a possible tweaking of the paragraph was discussed, so that it should also include female homosexuality. Calls for the abolition appeared regularly in editions of the "Bundes für Menschenrecht", partly also without explicit reference to lesbians.[8]

Die Freundin remained, on the whole, rather hesitant on issues concerning political parties. Irene von Behlau recommended the election of the Social Democratic Party in her article "The Gay Woman and the Reichstag Election" of 14 May 1928. From 1930, a kind of neutrality was necessary, since statistics of the year 1926 had made clear to the BfM that they had members of both left and right parties. There was an emphasis on voting for parties which would work toward the abolition of §175.[13] After some recently discovered cases of "same-sex-loving people" in Hitler's NSDAP (Nazi) party, who were "the most efficient and best party members", the publisher Friedrich Radszuweit wrote an open letter to Adolf Hitler in August 1931 encouraging him "to allow the deputies of the party to vote in the Reichstag for the abolition of § 175".[16]

All efforts seem to have failed to involve the readers of Die Freundin politically. There were regular complaints about the alleged passivity of the readers.[12]

Fiction

[edit]The literary section of the magazine consisted of short stories, romance and poems on lesbian love. In addition, there were always book recommendations and reviews of books, of which many were published by the "Friedrich Radszuweit Verlag".[8][5]

The literary texts contributed to the popularity of Die Freundin. They weren't written by academic professionals, but by the readers. These works were broadly considered trivial without great significance. They were crucial in portraying lesbian ways of life and in formulating utopias. These stories discussed the lesbian love experience, the problems of the search for a female partner and discrimination, always ending with the sense that these problems could be overcome. Doris Claus, for example, emphasized the liberating value of the work in her analysis of the novel "Arme Kleine Jett" by Selli Engler, who was featured in Die Freundin in 1930. In imagining the lesbian way of life as existing openly in the context of Berlin's vibrant arts scene, without conflicts or stigmas, he created a world view which lesbians could imagine themselves in.[26]

Hanna Hacker and Katharina Vogel even consider the stylistic means of "trivial literature" as crucial for understanding the lesbian condition, since the use of "stereotypes by lesbian women also helps develops and stabilize their own culture".[12]

Classifieds

[edit]Classifieds were always featured in the back of the magazine. In addition to various forms of contact ads, it mainly contained job advertisements, event notices, and advertisements for local businesses and books. The classified were only accepted through members of the BfM, which in turn led to many businesses becoming members in order to be featured in the classifieds. This method strengthened the association and its weight in the gay and lesbian movement, especially since the readership was encouraged to visit only those places recommended by BfM.[21][5]

Personal ads

[edit]There were two main kinds of personal ads. One type featured lesbians, gays or trans people looking for partners. Lesbians used the codes of their subculture, such as "Miss, 28 years, looking for an educated girlfriend", "Woman wishes sincere friendship with a well-disposed lady" or "Where to meet a girl of higher circles, possibly private?"[8]

A very different kind of personal ad was one advertising for so-called "companions". These sought marriages between a gay woman and a gay man in the hope that the status of marriage would offer some protection from anti-gay culture in case of prosecution.[8] The intention was unmistakable in advertisements such as: "27-year-old, of good origin, double-orphan, respectable, looking for a wealthy lady companion (also a business owner)."

Event postings

[edit]The classifieds also contained numerous events and advertisements from lesbian spaces, mostly within Berlin. Meetings and festivals of the so-called "women's clubs" also found their way into the editorial part if they were announced late. These clubs were remarkably large. 350 members were present at the fourth meeting of the "Violetta Club" women's costume workshop.[8][5] The "Erato Club", which was advertised in Die Freundin, rented dance halls with a capacity of 600 people for their events, giving a sense of how big these meetings were.[27]

Legacy

[edit]At the time of the Weimar Republic, a lesbian sense of self was talked about for the first time within the context of the early gay liberation movement. Berlin was the center of gays from all over Europe. The numerous magazines and newspapers devoted to homosexuality (albeit mostly with a masculine emphasis) led to a market for especially lesbian interests. Three such publications have been found to date, including Die Freundin, Frauenliebe (1926–1930), and Die BIF – Blätter Idealer Frauenfreundschaften (probably around 1926–1927) . Frauenliebe in particular often changed its name, which led to such titles as Frauenliebe, Liebende Frauen, Frauen Liebe und Leben and finally Garçonne (1930–1932).[28][29] Having started in 1924, Die Freundin was the most distributed lesbian magazine world-wide. Until the ban on all gay journals in 1933, it was the longest-lived lesbian publication of the Weimar Republic.

From today's perspective, Die Freundin is seen[by whom?] as "probably the most popular" among lesbian magazines[when?] and a "symbol of the lesbian identity in Berlin in the 1920s".[8] Florence Tamagne speaks of Die Freundin as an "accepted magazine that became a symbol of lesbianism in the 1920s".[5] Günter Grau regards it as "the most important magazine for lesbian women in the Weimar Republic of the 1920s".[16] Angeles Espinaco-Virseda characterized Die Freundin as a "publication in which science, mass culture and subculture overlap", a magazine "which directly addressed women, articulated their longings and offered them new concepts and choices for gender roles, sexuality, and partnerships; and consequently offered a different sense of lesbian identity. "[21]

Individual surviving readers' voices support this, especially in Berlin. For example, Angeles Espinaco-Virseda quotes a reader: "Through the magazine I learned valuable information about myself and that I was, in no way, unique in this world."[21] A reader from Essen wrote: "For years I have searched in vain for a source of entertainment which brings our kind of people closer to each other through the means of word and writing, the sisters make hours of solitude worthwhile when I visit Hildesheim - a small and strictly religious town."

In spite of the popularity of the magazine, Charlotte Wolff, who lived at the time as a lesbian in Berlin, reported, after reading the magazines for the first time in 1977: "I had never heard of Die Freundin at the time of its publication, a sure sign of the mystery surrounding its appearance, even though gay films and plays were fashionable in the 1920s. Die Freundin was obviously an 'illegitimate child' who did not dare to show its face publicly. The lesbian world that depicted it had little in common with the gay women I knew and the places I frequented. Their readers came from another class, who loved, drank, and danced in another world.[4]

Research

[edit]Die Freundin met the same fate as most other gay journals of the time: they "were hardly been paid attention to by major historical research, with the exception of some essays and unpublished dissertations".[12] Heike Schader's work "Virile, Vamps und wilde Veilchen" from 2004 was the first time a more comprehensive work had been drafted on Die Freundin, which took an academic approach on the source material. Until then, Die Freundin had only one major feature in an exhibition catalog as well as two university works.[12] As the most popular and widespread magazine for gay women of the Weimar Republic, it has been given additional attention since the popularization of lesbian publications. In 2022 the Forum Queeres Archiv München digitized 194 issues of Die Freundin.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Corey K. Creekmur; Alexander Doty (1995). Out in culture: gay, lesbian, and queer essays on popular culture. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-304-33488-9. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ Robert Aldrich; Garry Wotherspoon (21 February 2003). Who's who in gay and lesbian history: from antiquity to World War II. Psychology Press. p. 445. ISBN 978-0-415-15983-8. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ a b Friederike Ursula Eigler (1997). The feminist encyclopedia of German literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-313-29313-9. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Magee, Diana C.; Miller, Maggie (December 1997). Lesbian lives: psyschoanalytic narratives old and new. Analytic Press. pp. 350–351. ISBN 978-0-88163-269-9. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tamagne, Florence (2006). A History of Homosexuality in Europe, Berlin, London, Paris 1919–1939. Algora. pp. 77–81. ISBN 9780875863573.

- ^ a b c Leila J. Rupp (1 December 2009). Sapphistries: a global history of love between women. NYU Press. pp. 193–196. ISBN 978-0-8147-7592-9. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ B. Ruby Rich (January 1998). Chick flicks: theories and memories of the feminist film movement. Duke University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-8223-2121-7. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Hürner, Julia (2010). "Lebensumstände lesbischer Frauen in Österreich und Deutschland - von den 1920er Jahren bis zur NS-Zeit" (PDF). pp. S. 38–43 & 46–52.

- ^ "Cover". Die Freundin. 2 (5). 1925.

- ^ "Cover". Die Freundin. 3 (20). 1927.

- ^ a b "Cover". Die Freundin. 8 (36). 1932.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schader, Heike (2004). Virile, Vamps und wilde Veilchen. Sexualität, Begehren und Erotik in den Zeitschriften homosexueller Frauen im Berlin der 1920er Jahre. Ulrike Helmer Verlag. pp. 43–48 & 63–72. ISBN 3-89741-157-1.

- ^ a b c d e Vogel, Katharina (1984). "Zum Selbstverständnis lesbischer Frauen in der Weimarer Republik : eine Analyse der Zeitschrift "Die Freundin" 1924-1933". Eldorado : homosexuelle Frauen und Männer in Berlin 1850–1950 ; Geschichte, Alltag und Kultur. Rosa Winkel. pp. 162–168. ISBN 3-88725-068-0.

- ^ Schlierkamp, Petra (1984). "Die Garçonne". Eldorado. Homosexuelle Frauen und Männer in Berlin 1850–1950. Rosa Winkel. pp. 162–168. ISBN 3-88725-068-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Micheler, Stefan (2005). "Zeitschriften, Verbände und Lokale gleichgeschlechtlich begehrender Menschen in der Weimarer Republik". Selbstbilder und Fremdbilder der "Anderen". Männer begehrende Männer in der Weimarer Republik und der NS-Zeit (PDF). Universitätsverlag Konstanz.

- ^ a b c d Grau, Günter (2011). "Institutionen - Kompetenzen - Betätigungsfelder". Lexikon zur Homosexuellenverfolgung 1933–1945. Lit Verlag. pp. 329, 59, 235–236. ISBN 978-3-8258-9785-7.

- ^ "Cover". Die Freundin. 4 (10). 1928.

- ^ Weber, Aenne (2015). Persönlichkeiten in Berlin 1825–2006. Erinnerungen an Lesben, Schwule, Bisexuelle, trans- und intergeschlechtliche Menschen. Berlin: Senatsverwaltung für Arbeit, Integration und Frauen. p. 76. ISBN 978-3-9816391-3-1.

- ^ a b Aldrich, Robert; Wotherspoon, Garry (7 October 2020). Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History: From Antiquity to the Mid-Twentieth Century. London, UK: Routledge. p. 445. ISBN 978-1-000-15888-5.

- ^ "Briefkasten". Die Freundin. 8 (37): 7. 1932.

- ^ a b c d Espinaco-Virseda, Angeles (2004). "I feel that I belong to you" - Subculture, Die Freundin and Lesbian Identities in Weimar Germany". Spaces of identity: tradition, cultural boundaries & identity formation in Central Europe. Edmonton: Univ. of Alberta. pp. 83–100.

- ^ Sutton, Katie (2012). ""We Too Deserve a Place in the Sun": The Politics of Transvestite Identity in Weimar Germany". German Studies Review. 35 (2): 335–354. ISSN 0149-7952. JSTOR 23269669.

- ^ Es, Lina (1927). "Meinungsaustausch der Transvestiten". Die Freundin. 3 (8).

- ^ Es, Lina (1927). "Die Transvestiten und die Polizei" (PDF). Die Freundin. 3 (16).

- ^ Simon, Toni (1929). "Angeklagter in Frauenkleidung" (PDF). Die Freundin. 5 (13).

- ^ Claus, Doris (1987). Selbstverständlich lesbisch in der Zeit der Weimarer Republik. Eine Analyse der Zeitschrift "Die Freundin". Bielefeld. pp. 76–93.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Leidinger, Christiane (2008). "Eine "Illusion von Freiheit" – Subkultur und Organisierung von Lesben, Transvestiten und Schwulen in den zwanziger Jahren". Boxhammer, Ingeborg/Leidinger, Christiane:Online-Projekt Lesbengeschichte. Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Peters, Jean (1 March 2011). "Spinnboden Lesbenarchiv und Bibliothek". Die Tageszeitung.

- ^ Smits, Karina; van Voorst, Sandra; Broomans, Petra (2012). "Die Freundin and Other Relationships: A Proposal for a Comparative Study of the Role of Lesbian Magazines within the Process of Cultural Transfer and Transmission". Rethinking Cultural Transfer and Transmission: Reflections and New Perspectives. Barkhuis. pp. 131–137. ISBN 978-9491431197.

- ^ Digitized Issues on Forum Queeres Archiv München

External links

[edit] Media related to Die Freundin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Die Freundin at Wikimedia Commons

- 1924 establishments in Germany

- 1933 disestablishments in Germany

- Defunct German-language magazines

- Lesbian culture in Germany

- Defunct LGBTQ-related magazines published in Germany

- 1930s LGBTQ-related mass media

- 1920s LGBTQ-related mass media

- Defunct lesbian-related magazines

- Magazines established in 1924

- Magazines disestablished in 1933

- Magazines published in Berlin

- First homosexual movement